Abstract

Numerous human diseases can be associated with fungal infections either as potential causative agents or as a result of changed immune status due to a primary disease. Fungal infections caused by Candida species can vary from mild to severe dependent upon the site of infection, length of exposure, and past medical history. Patients with impaired immune status are at increased risk for chronic fungal infections. Recent epidemiologic studies have revealed the increasing incidence of candidiasis caused by non-albicans species such as Candida parapsilosis. Due to its increasing relevance we chose two distinct C. parapsilosis strains, to describe the cellular innate immune response toward this species. In the first section of our study we compared the interaction of CLIB 214 and GA1 cells with murine and human macrophages. Both strains are commonly used to investigate C. parapsilosis virulence properties. CLIB 214 is a rapidly pseudohyphae-forming strain and GA1 is an isolate that mainly exists in a yeast form. Our results showed, that the phagocyte response was similar in terms of overall uptake, however differences were observed in macrophage migration and engulfment of fungal cells. As C. parapsilosis releases extracellular lipases in order to promote host invasion we further investigated the role of these secreted components during the distinct stages of the phagocytic process. Using a secreted lipase deficient mutant strain and the parental strain GA1 individually and simultaneously, we confirmed that fungal secreted lipases influence the fungi's virulence by detecting altered innate cellular responses. In this study we report that two isolates of a single species can trigger markedly distinct host responses and that lipase secretion plays a role on the cellular level of host–pathogen interactions.

Keywords: Candida parapsilosis, phagocyte response, secreted lipase, co-infection, live cell imaging

Introduction

Candida species are the most common etiological agents of systemic fungal infections (Gácser et al., 2005). Although Candida albicans is the leading Candida species responsible for bloodstream infections, a significant increase has been reported in the number of fungal invasions caused by non-albicans Candida (NAC) species (Guinea, 2014). C. parapsilosis is one of the most frequent NAC species found in the hospital environment and currently is the number one cause of neonatal candidemia (Chow et al., 2012; Pammi et al., 2013; Guinea, 2014; Quindos, 2014). Besides its association with nosocomial infections in children, this species also threatens adult patients with diminished immunity (Nosek et al., 2009). Despite the emerging relevance of C. parapsilosis, relatively little is known about the immune responses induced by this species. GA1 and CLIB 214 are two distinct C. parapsilosis clinical isolates that are the most frequently used model strains for biological and molecular characterization studies (Gácser et al., 2005; Holland et al., 2014). C. parapsilosis GA1 is a bloodstream isolate obtained in Hamburg, Germany, and primarily appears in a yeast form and produces smooth colonies on agar (Trofa et al., 2008; Pryszcz et al., 2013). C. parapsilosis CLIB 214 (ATCC 22019) was isolated from the feces of a patient in Puerto Rico, and rapidly forms pseudohyphae producing a rough, concentric colony phenotype on agar (Laffey and Butler, 2005; Nosek et al., 2009). To our knowledge, no comparison has been made between the virulence of these commonly used laboratory type strains.

The phagocytic cells of the innate immune system play a central role in host defense against invading microbes, including fungi. The phagocytic process can be separated into four distinct stages: (1) phagocyte aggregation at the site of infection, (2) recognition of pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) via receptors, (3) internalization of the foreign particles, and (4) digestion of ingested agents through phagosome maturation and activation of hydrolytic enzymes (Lewis et al., 2013; Rudkin et al., 2013). We recently investigated the phagocytosis of C. parapsilosis CLIB 214 focusing on migration and engulfment of these cells by macrophages, and compared the results to that occurring with C. albicans and C. glabrata (Tóth et al., 2014b). In the present study, one of our primary aims was to compare and define the interactions of C. parapsilosis GA1 and CLIB 214 with host effector cells.

One well-described virulence factor that promotes the pathogenesis of invasive candidiasis is the secretion of hydrolytic enzymes, such as lipases and proteinases (Gácser et al., 2007; Horváth et al., 2012). Presumed roles of microbial secreted lipases during an infection include host cell adhesion, lipid digestion for nutrient acquisition and triggering of inflammatory cascades (Trofa et al., 2008; Nguyen et al., 2011; Tóth et al., 2014a). Secreted lipase encoding genes have been identified in C. parapsilosis (Gácser et al., 2007). In contrast with C. albicans, the C. parapsilosis genome includes only four putative secreted lipases (Butler et al., 2009; Nguyen et al., 2011). However, the deletion of only two of the four lipase encoding genes (LIP1 and LIP2), resulted in significantly decreased virulence as determined in both in vitro and in vivo infection models (Nagy et al., 2011; Trofa et al., 2011). In addition, the deletion mutant strain lacking both LIP1 and LIP2 (CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2) formed less complex and thinner biofilms when compared to the C. parapsilosis GA1 parental strain (Gácser et al., 2007). Studies that used human peripheral blood mononuclear cell-derived macrophages (PBMC-DMs; Tóth et al., 2014a) and dendritic cells (DCs; Nagy et al., 2011) reported CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 strain to be less virulent, as both types of primary cells killed lipase mutant cells at a higher ratio than wild type cells. Furthermore, the lack of the secreted component, increased the pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine expression levels, thus led to stronger inflammatory response (Nagy et al., 2011; Tóth et al., 2014a). The decreased virulence of CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 was also reflected in the rate of reconstituted human tissue damage as the infected tissue was similar to the uninfected control and low LDH levels were measured (Gácser et al., 2007). Another study, using neonatal rats also confirmed these results, as low levels of organ fungal burdens were detected (Trofa et al., 2011).

Hence, the data show that secreted lipases play a role in C. parapsilosis virulence. Therefore, another major aim of the present work was to determine how secreted lipases influence the phagocytic process by examining the separate stages individually and if the presence of the wild type strain could complement the defective phenotype of CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 and thus influence the phagocyte response.

Thus, in this study we compared the phagocytosis of CLIB 214 by macrophages to that of GA1 and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 cells using live cell imaging at defined stages of the phagocytic process: phagocyte migration, engulfment of fungal cells, and subsequent host cell damage. Additionally, co-infections with CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 and GA1 fungal cells were performed to determine whether secreted factors from wild type cells could complement the defects in the mutant yeasts.

Materials and methods

Preparation of Candida parapsilosis strains

Wild type C. parapsilosis CLIB 214 and GA1 clinical isolates and the LIP1–LIP2 deficient strain (CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2) were maintained on YPD solid medium at 4°C and prepared for experiments as described in our previous work (Tóth et al., 2014b). Prior to experiments, the Candida strains were cultured overnight in liquid YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% glucose, 2% peptone) at 30°C with shaking at 200 rpm. The cells were collected and washed three times with PBS (phosphate buffered saline), counted and diluted to the final concentration of 1 × 108/ml. UV-killed fungal strains were prepared using twenty exposures to 20 mJ/cm−2 UV. In order to differentiate between fungal cells after the co-infection, 1 mg/ml FITC (Sigma, Dorset, UK) and 50 μg/ml CFW (Sigma, Dorset, UK) were used to label yeasts. FITC was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and added to 108/ml cells suspended in 0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6). CFW was dissolved in distilled water and added to 108/ml yeasts in PBS. C. parapsilosis cells were stained at room temperature in the dark for 10 min, followed by washing steps three times with PBS and suspended in 1 ml 1X PBS. In dual yeast cell co-infection experiments, mixtures of GA1 and LIP1–LIP2 yeast cells were used in which GA1 was labeled with FITC and the mutant with CFW. Experiments were simultaneously performed using GA1 yeast cells labeled with CFW and mutants with FITC. We found that there was no difference in our experiments whether the GA1 or lipase mutants were labeled with the alternate stain. Although we used both conditions in all experiments, we only reported out the condition where GA1 was labeled with FITC and the mutant with CFW.

J774 mouse macrophage cell line preparation and staining

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Lonza, Slough, UK) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK), 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Biosera, Ringmer, UK), and 200 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) was used in order to maintain the murine cell line. J774 cells were kept at 37°C, in the presence of 5% CO2 prior to and during the experiments. For live video microscopy, similarly to our previous report, 1.2 × 105 macrophages were seeded on eight-well μ-slides (ibidi, Martinsried, Germany) and incubated at 37°C overnight prior to infection with Candida strains. For visualizing phagocytosis Lysotracker Red was used to label the acidic compartments of phagocytes. The original media was replaced with fresh, 300 μl pre-heated supplemented DMEM containing 1 μM Lysotracker Red DND-99 (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) immediately before the experiments.

Human PBMC-derived macrophage preparation and staining

For the isolation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), a standard protocol was used (Rudkin et al., 2013) with modifications, under approval from the institutional review board of the University of Aberdeen and the University of Szeged. Following isolation, PBMCs (7.5 × 105 cell/ ml) were then plated on eight-well μ-slides (ibidi, Martinsried, Germany) and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 6–7 days in serum supplemented DMEM (Lonza, Slough, UK). Shortly before the experiment, similarly to the murine macrophage preparation, the media was replaced with 300 μl fresh, pre-heated supplemented and 1 μM Lysotracker Red DND-99 (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) containing DMEM.

Phagocytosis assay and live cell video microscopy

In order to examine the phagocytic processes post infection, a previously described and standardized protocol was used accordingly (Tóth et al., 2014b). Live and UV-treated C. parapsilosis CLIB 214, GA1, and ΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 cells were added to Lysotracker red DND-99-stained (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK; 1 μM) 4 × 105 /ml J774 murine and 7.5 × 105 /ml human PBMC-derived macrophages on eight-well μ-slides (ibidi, Martinsried, Germany) in 300 μl volumes immediately before the video capture was initiated. During individual infections, the effector/target ratio was 3:1, while in the case of simultaneous infections the ratio of 1.5 GA1: 1.5 lipase mutant: 1 macrophage was used. Images were captured over a 6 h period with a CCD camera attached to an UltraVIEW VoX Spinning disc confocal microscope (PerkinElmer, Massachusetts, USA) using a 40X oil immersion objective. For the comparison of the C. parapsilosis GA1 and CLIB 214 clinical isolates, over a 100 J774 macrophages were monitored individually and evaluated from at least four separate experiments—with 20–40 macrophages analyzed per experiment, dependent on frequency of macrophage–Candida interactions in the respective videos. From PBMC-DM experiments, 60 macrophages were tracked from three separate experiments with 15–20 macrophages analyzed per experiment due to cell size. For the C. parapsilosis GA1 and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 comparison 250 macrophages were selected and monitored from five separate experiments, with 45–55 macrophages followed per experiment, dependent on frequency of macrophage–Candida interactions in the respective videos, in order to make clear assumptions from the co-infection studies.

For tracking and statistical analysis of both murine and human PBMC-derived macrophage migration Volocity 6.3 image analysis software (Improvision, PerkinElmer, Coventry, UK) was used. Similarly to our previous study, measurements included the macrophage migration toward C. parapsilosis cells, distribution of fungal cells per macrophages, prevalence of uptake events, engulfment time, average uptake of fungal cells by actively phagocytosing macrophages and post-ingestion rupture events of host cells.

High throughput analysis with Volocity software 6.3 allowed us to calculate the mean tract velocity of macrophages in the presence of different C. parapsilosis strains. The engulfment time was defined as the time difference between the establishment of the phagocyte-fungal cell contact and the phagocyte membrane enclosing around the fully ingested cell. Full engulfment events were determined when macrophages stretched toward fungal cells, the phagocyte membrane encircled around the yeast cell and the host cell regained its original shape. The prevalence of uptake represents the percentage of uptake events during defined time intervals. Individual events were defined by the starting point of the recognition of fungal cells by macrophages. The percentage of macrophages taking up specific numbers of fungal cell was referred to as distribution of fungal cells per macrophages. Average uptake is defined as the average number of fungal cells taken up by phagocytes that ingested at least one yeast cell over the whole incubation period. The percentage of dead macrophages relative to the visible macrophage population, that ingested at least one C. parapsilosis cell, represents post-ingestion macrophage rupture (PIR) events. Individual PIR events were defined as the disruption of membrane integrity that were visible up until the end of the 6 h of co-culturing period.

LDH assay to determine host cell damage

To determine the concentration of LDH released by macrophages, culture supernatants were collected 6 h after C. parapsilosis infection. As a postive control, cells were treated with 1% Triton X-100 solution. For LDH detection, the Cytotoxycity Detection kit (Takara Bio Europe/Clontech, France) was used according to the user's manual. Basal LDH activity of human PBMC-derived macrophages may be due to the presence of undifferentiated monocytic cells or dead cells in the culture before the assay.

Statistical analysis

Tracking of individual macrophages and high-throughput migration analysis was achieved by Volocity software 6.3. Extracted data were used to calculate the mean track velocity of phagocytes cultured with Candida strains.

For the comparison of the calculated mean values of each of the aspects, student's unpaired, two-tailed t-tests were used and confirmed by One-way ANOVA analysis followed by a Bonferroni's multiple comparison post-hoc tests. GraphPad Prism v 5.0 software was used to determine statistical significance. Significant differences were considered at p-values of ≤ 0.05. Data were pooled for migration analysis, engulfment time and LDH, thus SD-values are shown, percent phagocytosis, average uptake values and data for the fungal cell distribution/macrophages were evaluated as mean of means, thus SEM-values indicate error.

Results

Comparison of C. parapsilosis GA1 and CLIB 214 isolates

Macrophage migration differs for C. parapsilosis CLIB 214 and GA1 isolates

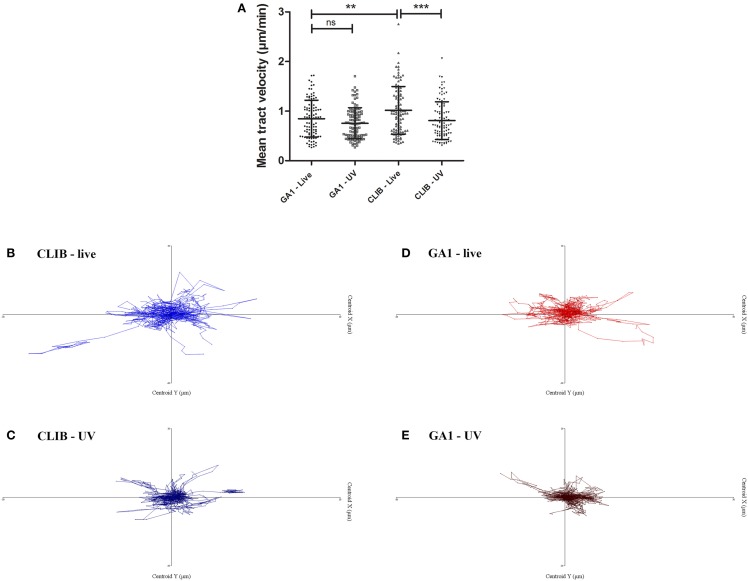

Murine macrophages were challenged with live or UV-killed C. parapsilosis GA1 or CLIB 214 cells at an effector/target ratio of 1:3 and the phagocytic process was monitored by live cell video microscopy for 6 h (Lewis et al., 2012; Okai et al., 2015). We first examined the migration of macrophages toward the two distinct isolates. As the majority of uptake events were detected during the early stages post infection, macrophages were tracked during the first 45 min. Interestingly, the track velocity of J774 macrophages in response GA1 was significantly lower (mean ± SD; 0.85 ± 0.37 μm/min, Figure 1A) than to CLIB 214 (1.02 ± 0.48 μm/min). UV-killing of CLIB cells led to a significant reduction in the velocity of macrophage migration (0.81 ± 0.38 μm/min). In contrast, the difference between live and dead GA1 (0.75 ± 0.31 μm/min) was not significant, and the track velocity was similar to that of UV-irradiated CLIB yeast cells. These differences are also evident in the macrophage tracking diagrams (Figures 1B–E). The tracking diagrams show the movement and distances traveled by individual phagocytes relative to their starting position. The tracked murine macrophages appeared to travel shorter distances toward both UV-killed CLIB 214 and GA1 cells (Figures 1C,E) than toward live CLIB 214 and GA1 yeasts (Figures 1B,D).

Figure 1.

Macrophage migration toward C. parapsilosis GA1 and CLIB 214. J774 murine macrophages were challenged with live or UV-treated C. parapsilosis GA1 or CLIB 214 cells and were tracked individually using Volocity 6.3 software in defined time intervals. Mean track velocity values were calculated (mean ± SD) in μm/min (A). Tracking diagrams show the movement and distances traveled by phagocytes relative to their starting position after culturing with live (B) or UV-killed (C) CLIB 214, and live (D) or UV-treated (E) GA1 cells. One-way ANOVA analysis with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test was used to determine statistical relevance. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

CLIB 214 and GA1 exhibit altered engulfment dynamics during macrophage phagocytosis

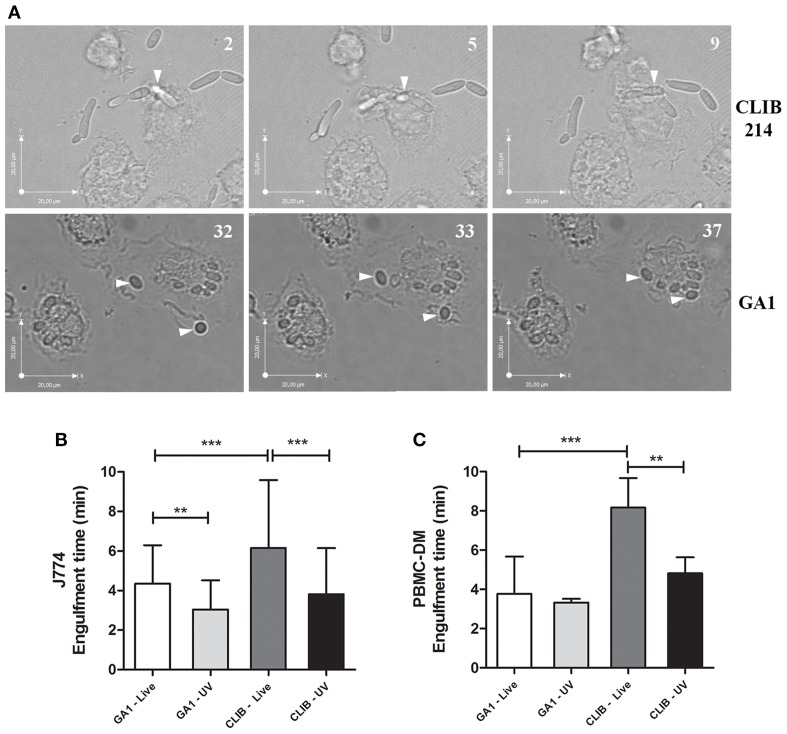

In this study we further aimed to differentiate between the time taken to internalize GA1 and CLIB 214 by murine and human PBMC-derived macrophages. Differences were observable in phenotype between the two isolates of C. parapsilosis as shown on Figure 2A, as rapid pseudohypha formation was detectable in CLIB 214 but not with the GA1 strain. At the early stage of infection, C. parapsilosis GA1 does not form pseudohyphae, only slightly elongated blastospores. Engulfment time is defined as the time from the first phagocyte-fungal cell contact and the macrophage fully enclosing the bound cell. According to our analyses, both J774 phagocytes and the human PBMC-derived macrophages required significantly less time to internalize GA1 yeast cells (mean ± SD; 4.36 ± 1.94 and 3.77 ± 1.9 min for J774 and PBMC-derived macrophages, respectively, Figures 2B,C) compared to CLIB 214 cells (6.16 ± 3.43 and 8.16 ± 6.41 min). Furthermore, UV-treatment significantly decreased the engulfment time by J774 macrophages of GA1 and CLIB 214 yeast cells (3.05 ± 1.47 and 3.82 ± 2.32 min, respectively; Figure 2B). A similar trend for the engulfment of UV-irradiated cells was shown when using human primary macrophages.

Figure 2.

Engulfment time of GA1 and CLIB 214 by macrophages. Representative images show the full internalization of C. parapsilosis CLIB 214 (A, upper panel) and GA1 cells (A, lower panel) by human PBMC-derived macrophages. Numbers at the upper right corner of pictures show the time (minutes) of observed individual events. Arrows show the fungal cells internalized by phagocytes. Diagrams show the average time (mean-values + SD) in minutes required for the full ingestion of live or UV-treated GA1 and CLIB 214 cells by J774 (B) and PBMC-derived macrophages (C). One-way ANOVA analysis with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test was used to determine statistical significance. Significant differences were considered at p-values **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm.

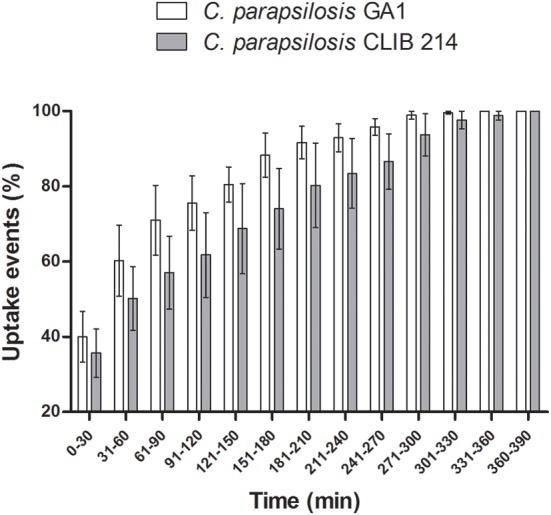

Uptake rates for the C. parapsilosis clinical isolates

The majority of fungal cells were phagocytosed during the first hour post-infection by murine macrophages (Figure 3). We observed no difference between the overall uptake of GA1 and CLIB 214 cells for both the murine and primary macrophages even though the primary cells showed a higher capacity for phagocytosis (Supplementary Figure 1). In general, the total uptake pattern of contribution of individual macrophages to overall uptake appeared to be similar for both clinical isolates and no statistically significant differences were observed in the average uptake of yeasts by both types of phagocytes (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Uptake kinetics of GA1 and CLIB 214. Percentage of uptake events (mean ± SEM) following the co-incubation of J774 murine phagocytes with live C. parapsilosis GA1 or CLIB 214 cells. Individual events are associated with the beginning of fungal cell recognition by macrophages. Data were analyzed using Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post-test. No differences were found after the evaluation.

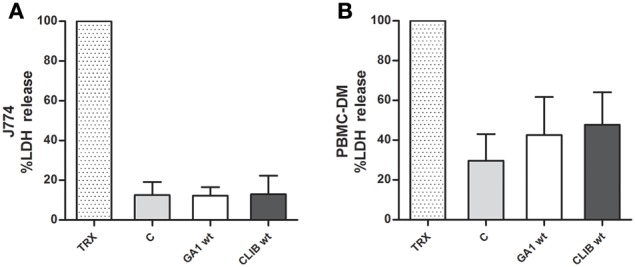

Host cell damage by CLIB 214 and GA1

In order to examine the impact of yeast cells on the host effector cells, macrophage damage was measured by the amount of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into supernatant after co-incubation with C. parapsilosis cells. Culture supernatant was collected 6 h after interaction with J774 phagocytes and human PBMC-derived macrophages, respectively. No differences were detected between the two C. parapsilosis clinical isolates in terms of their ability to damage either J774 (Figure 4A) or human macrophages (Figure 4B). LDH results were also confirmed by quantifying post-ingestion macrophage rupture events (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Macrophage damage by GA1 and CLIB 214. Host cell damage (mean + SD) was measured by the amount of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released by murine J774 (A) and human PBMC-derived (B) macrophages following incubation with live C. parapsilosis GA1 or CLIB 214 cells. In order to reach maximum LDH release Triton X-100 (TRX) was used. The supernatant of fungal-free cultured phagocytes was used as control “C”.

Role of fungal lipase secretion on phagocytosis

Comparison of C. parapsilosis GA1 and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 cells

Murine macrophages were infected with C. parapsilosis GA1 or CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 individually in a ratio of 3:1. In the case of co-infection, GA1 and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 cells were used in the ratio of 1:1, and the MOI was kept at 3:1 (representative image shown on Figure 5). In the mixed infections, yeast cells were either labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or calcofluor white (CFW).

Figure 5.

Infection of murine J774 macrophages with C. parapsilosis GA1 and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 cells, simultaneously. The image series show four channels of the co-infection of J774 macrophages with GA1 and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 cells. Channel (A), Lysotracker red stained acidic compartments of phagocytic cells; channel (B), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) stained CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 yeasts; channel (C), Bright-field image; channel (D), Calcofluor white (CFW) stained GA1 cells; channel (E), merged image. Images were taken immediately after infection (T = 0 min). Scale bar: 10 μm.

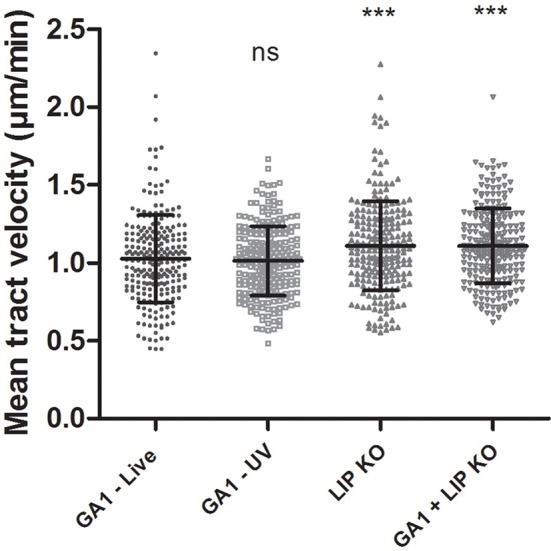

Migration toward wild type and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 mutant strain

We assessed the migration of macrophages toward CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2, GA1 or mixed CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 and GA1 yeast cells during the first 45 min of co-incubation as above. The mean track velocity of J774 macrophages was significantly higher toward CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 (mean ± SD; 1.11 ± 0.28 μm/min; Figure 6) compared to GA1 (1.03 ± 0.28 μm/min). Interestingly, the macrophage migration was similar to that of CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 when both GA1 and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 were present (1.11 ± 0.24 μm/min, Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Macrophage migration toward GA1, CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 or GA1, and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 cells. J774 murine macrophages were followed for 6 h after co-culturing with GA1 or CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 cells individually, and after GA1 and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 simultaneous infections. Phagocyte mean track velocity values (mean ± SD) are shown in μm/min. One-way ANOVA analysis with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test was used to determine statistical relevance. Significance was determined relative to the wild type. Different gray symbols represent the mean tract velocity of individual macrophages. ***p < 0.001.

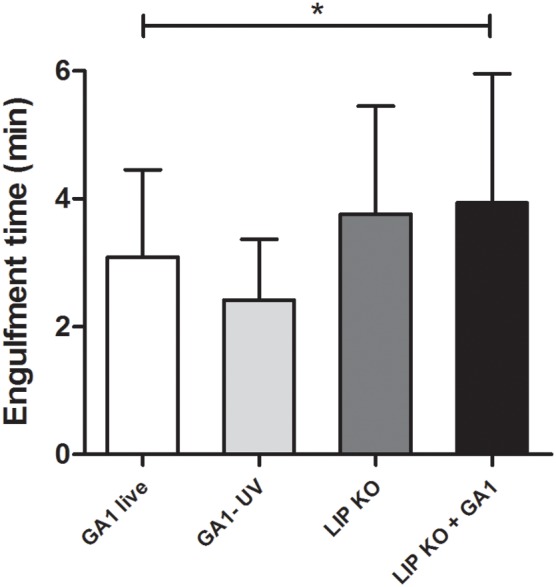

Differences in engulfment time of GA1 and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2

We also assessed whether there were differences in the engulfment times of C. parapsilosis GA1 and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 cells by macrophages (Figure 7). Our results indicated, that more time was required for the full internalization of CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 cells (mean ± SD; 3.76 ± 1.68 min; p = 0.07), in comparison with GA1 yeasts (3.09 ± 1.36 min). Mixed cultures of GA1 and lipase mutant yeasts had engagement times that were significantly increased relative to GA1 alone (3.948 ± 1.95 min, Figure 7), but were similar to the lipase mutants alone.

Figure 7.

Time required for the engulfment of GA1 and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2. Diagrams show the average engulfment time (mean + SD in minutes) of live and UV-killed GA1 and LIP KO cells by J774 murine macrophages. Data were analyzed using One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post-test. Statistical significances were considered at p-values *p < 0.05.

Differences in the phagocytosis of GA1 and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2

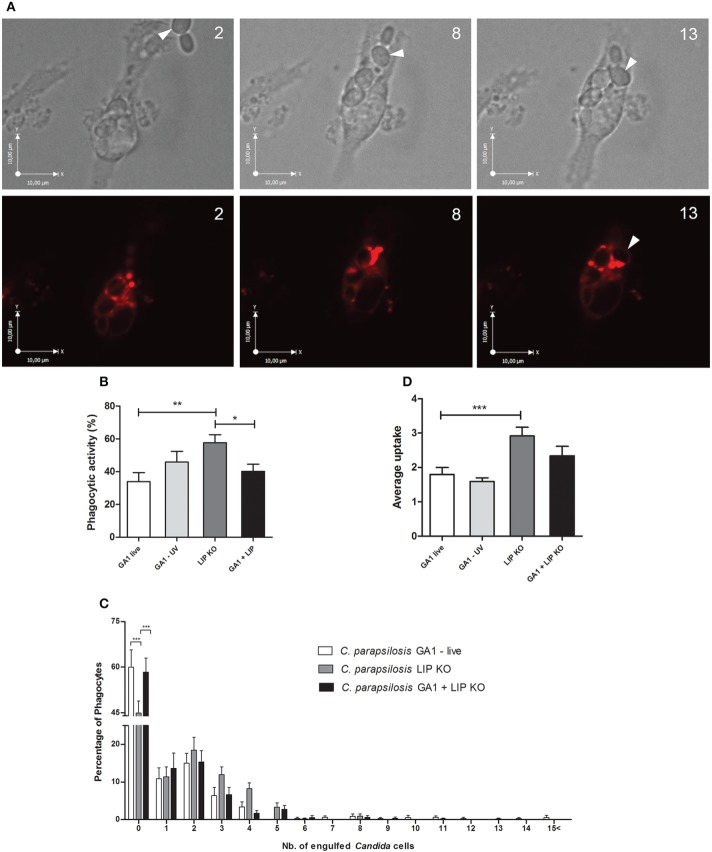

We further examined the overall uptake of C. parapsilosis GA1 and the lipase deficient mutant strain by J774 macrophages. Representative images of CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 phagocytosis are shown on Figure 8A. In general, the overall uptake of mutant cells was more efficient than GA1 cells. Co-infection of phagocytes with both strains (Supplementary Video 1) led to less effective overall phagocytosis as shown here by the intermediate values. Our results showed that, significantly more J774 macrophages contributed to the uptake of lipase deficient cells (mean ± SEM; 57.62 ± 4.95%) compared to their interactions with GA1 yeasts (33.90 ± 5.53%, Figure 8B). There was a significant reduction in uptake of yeast cells in conditions in which both CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 and GA1 were present compared to the lipase mutant alone. A higher percentage of macrophages took up more than two or three CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 cells than GA1 cells (Figure 8C). The mean number of ingested yeast cells was significantly higher with CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 infection (mean ± SEM; 2.91 ± 0.25) compared to GA1 (1.79 ± 0.20) or co-infections with GA1 and lipase mutants (2.32 ± 0.20 Figure 8D). We found no difference in uptake kinetics for both types of strains either in case of single or co-infections (data not shown). No difference was detected between CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 or GA1 cell preference of the individual macrophages and no differences were observed in CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 or GA1 uptake, when both stains were present with the host cells (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Overall uptake of GA1 and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 by J774 macrophages. On Panel (A) bright field and fluorescent microscopic images show the internalization of CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 cells (arrows) by a J774 murine macrophage. Phagocyte was stained with Lysotracker Red. Numbers indicate the duration of time (min) from recognition until the complete ingestion of cells. Scale bar: 10 μm. Panels (B–D) represent the overall uptake of fungal cells showing phagocytic activity (mean + SEM; B), defined number of fungal cells taken up by phagocytes (mean + SEM; C) and average uptake (mean + SEM; D). Data for phagocytic activity and average uptake were analyzed using One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post-test. Two-way ANOVA analysis with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test (column to column comparison) was applied to determine significant differences between the distribution of fungal cells per macrophages. Significant statistical differences: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

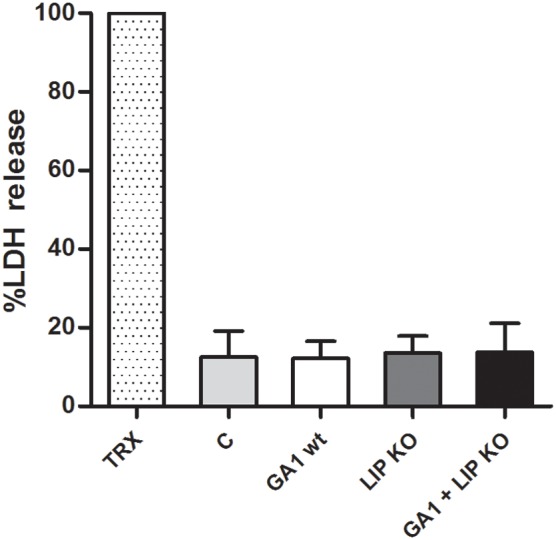

Macrophage damage by GA1 and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2

As a measure of host cell damage, LDH released by J774 phagocytes was measured from culture supernatant 6 h post-infection. Similar levels of LDH were detected with either individual; or mixed wild type and lipase deletion strains. Thus, the lack of LIP1 and LIP2 genes did not affect host cell damage (Figure 9). Similar observations were made when comparing the C. parapsilosis strains in terms of post-ingestion macrophage rupture events (data not shown).

Figure 9.

Host cell damage by GA1 and CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2. LDH release (percentage of mean + SD) was measured to determine macrophage damage 6 h after co-incubation with CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2, GA1 or mixed CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 and GA1 yeast cells. TRX: Triton X-100 treated macrophages; C: fungal-free cultured phagocytes.

Discussion

In our previous study, we compared the phagocytic kinetics of three Candida species, C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. parapsilosis CLIB 214 (Tóth et al., 2014b). Here we aimed to compare two well-described C. parapsilosis clinical isolates, GA1 and CLIB 214. In order to study the interaction between the innate immune system and C. parapsilosis clinical isolates on the cellular level, live cell imaging was used, which has previously been validated as a high-throughput image analysis tool for quantitative analysis (Bain et al., 2014; Okai et al., 2015). We compared phagocyte migration, engulfment rate, overall uptake of fungal cells, and subsequent host cell damage after challenging murine and human PBMC-derived macrophages with fungal cells. Our results showed similar overall uptake rates for GA1 and CLIB 214 by both types of macrophages as fungal strains were ingested during the early phases of the co-incubation; no differences were detected in phagocytic activity, uptake kinetics or average uptake. However, significant differences were found in terms of macrophage migration and engulfment time. Recent publications have already used macrophage migration to differentiate between pathogenic strains, as it refers to recognition capabilities of either pathogenic PAMPs or microbial signaling molecules (Lewis et al., 2012; Ifrim et al., 2014). Thus, host cell migration rates might indicate virulence properties of pathogenic microorganisms. Interestingly, we determined that the mean velocity of macrophages significantly decreased when they were incubated with GA1 yeast cells compared to CLIB 214. In addition, UV-treatment of either strain led to decreased phagocyte migration, although this difference was not significant for GA1. This change in migration might be caused by different amounts of fungal signaling molecules released into the medium, thus differences between the metabolic activities of the two isolates. However, further investigations are needed to confirm this theory. Furthermore, our data suggested that significantly more time was required for the uptake of CLIB 214 cells in contrast with GA1, and UV treatment significantly decreased engulfment time of both strains. As we previously reported, even though C. parapsilosis CLIB 214 cells are able to form pseudohyphae rapidly post-infection, no correlation was found between the engulfment time and the length of pseudohyphae (Tóth et al., 2014b). Thus, the difference in the engulfment time of GA1 and CLIB 214 might suggest that this is due to differences between the cell wall PAMPs of the two isolates, rather than differences in terms of shape and length. Results based on LDH release and post-ingestion macrophage rupture events revealed that both C. parapsilosis isolates examined contributed equally to host cell damage.

Even though, C. parapsilosis GA1 and CLIB 214 isolates were phagocytosed similarly, dissection of the phagocytic stages revealed various host cell responses. These altered responses might suggest differences in the cell wall structure or composition and fungal signaling molecules released by these strains. However, further investigations are needed for confirmation. As both of these clinical isolates are commonly used laboratory strains for molecular characterization, this information might be taken into consideration when studying gene function.

Secreted hydrolytic enzymes play a critical role in host invasion by fungi (Ghannoum, 2000; Borst and Fluit, 2003; Schaller et al., 2005). Secreted lipases of Candida species are associated with host cell adhesion, tissue damage and inflammatory response induction (Hube et al., 2000; Trofa et al., 2009). While C. albicans is known to have 10 lipase encoding ORFs, only two lipase genes (LIP1–LIP2) have been identified in C. parapsilosis (Hube et al., 2000; Stehr et al., 2004; Gácser et al., 2007). Both C. parapsilosis GA1 and CLIB 214 are known to produce extracellular lipases. Although, the previously established C. parapsilosis lipase deficient strain is only available on a GA1 background, thus when studying the function of lipases during an infection, we compared these strains only. The virulence properties of the C. parapsilosis lipase deficient strain (CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2) have already been investigated. According to our previous findings, the deletion mutant was killed more efficiently, however, phagocytosed similarly by macrophages when compared to the wild type (Tóth et al., 2014a). As shown previously, examining the component stages of the phagocytic process can provide insights into host–pathogen interactions on the cellular level and therefore, reveal differences in the recognition, overall uptake, and engulfment processes (Tóth et al., 2014b; Bain et al., 2015). In this study we examined the phagocyte response toward the CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 lipase mutant and the parental strain GA1. Numerous preceding studies have used co-infection methods to gain insight into virulence attributes (Silva et al., 2011; Bou Ghanem et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2014). Thus, in order to investigate whether the absence of extracellular lipase in the CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 yeast cells could be overcome with the secretion of lipases by wild type yeasts during an infection, murine macrophages were challenged with wild type and lipase mutant yeasts individually, and simultaneously. In general, the overall macrophage uptake of mutant cells was more effective, as a higher percentage of phagocytes ingested a greater number of CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 cells compared to the wild type yeasts. In correlation with the uptake rates, murine macrophage migration was increased toward mutant cells, indicating enhanced recognition of CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 compared to wild type cells. These results suggest that, the lack of secreted lipase results in decreased virulence on the cellular level. Although, our current results are in contrast with a previous study on CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 and GA1 phagocytosis comparison (Tóth et al., 2014a), this is not the first report revealing differences in CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 phagocytosis. Nagy et al. have used dendritic cells to study the virulence properties of C. parapsilosis secreted lipases and also found increased phagocytic efficiency (Nagy et al., 2011). Interestingly, the engulfment time of the mutant cells was prolonged. This data might suggest that, deficiency in lipase secretion might have led to modified cell wall structure or alterations in the expressed PAMPs or alterations in the level of other potential secreted signaling molecules. Similarly to our previous report on host cell damage by CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2, we found no difference in murine macrophage damaging capacity compared to the wild type.

In conditions when both fungal strains were present, a significant reduction was observed in overall phagocytosis of yeast cells compared to the lipase mutant alone. Thus, lipase deficiency can be partially restored with the presence of the wild type cells that further confirms the role of fungal extracellular lipases during host–pathogen interactions. No difference was detected in yeast cell preference when macrophages were incubated with both types of fungal cells further supporting our hypothesis on secreted component deficiency complementation. The presence of wild type secreted lipases might had a direct influence on fungal cell uptake regardless of the yeast cell types present in the media. However, co-infection with GA1 and lipase mutant yeast cells increased the engulfment time similarly to CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2. This result can be explained by the above mentioned hypothesis on an additional deficiency of CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 that cannot be rescued with the presence of secreted lipases. Interestingly, co-infection of macrophages with both strains led to significantly increased macrophage migration. As shown above, the presence of the CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 cells increased the average track velocity markedly. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that in case of co-infection, the presence of the mutant cells might have unmasked a potential immune evasion ability in wild type cells. The presence of both strains simultaneously had no further effect on host cell damage compared to the wild type.

This study confirmed the role of secreted lipase in virulence, as lack of the secreted component resulted in decreased virulence by altering the dynamics of phagocytosis. Our results further showed that in terms of uptake, lipase deficiency is partially restored when the wild type strain is present, which further exemplifies the role of secreted lipases on phagocytosis.

In this report we have shown that two distinct isolates of a single species are able to trigger significantly different host responses and that fungal lipase secretion plays an important role in host–pathogen interactions on the cellular level.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Funding

RT's research was supported by the European Union and the State of Hungary, co-financed by the European Social Fund in the framework of TÁMOP 4.2.4. A/2-11-1-2012-0001 “National Excellence Program.” AG is supported by OTKA NN113153 and by NF84006. AG is further supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust Strategic Award for Medical Mycology and Fungal Immunology 097377 to LE. CV thanks the Visiting Professor Program, Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University, Riyadh.

Glossary

Abbreviations in figures

- LIP KO

indicates the CpΔΔlip1 − ΔΔlip2 lipase deficient strain

- TRX

represents Triton X-100.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01102

References

- Bain J., Gow N. A., Erwig L. P. (2015). Novel insights into host-fungal pathogen interactions derived from live-cell imaging. Semin. Immunopathol. 37, 131–139. 10.1007/s00281-014-0463-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain J. M., Louw J., Lewis L. E., Okai B., Walls C. A., Ballou E. R., et al. (2014). Candida albicans hypha formation and mannan masking of beta-glucan inhibit macrophage phagosome maturation. MBio 5, e01874. 10.1128/mBio.01874-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst A., Fluit A. C. (2003). High levels of hydrolytic enzymes secreted by Candida albicans isolates involved in respiratory infections. J. Med. Microbiol. 52, 971–974. 10.1099/jmm.0.05228-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bou Ghanem E. N., Jones G. S., Myers-Morales T., Patil P. D., Hidayatullah A. N., D'Orazio S. E. (2012). InlA promotes dissemination of Listeria monocytogenes to the mesenteric lymph nodes during food borne infection of mice. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1003015. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler G., Rasmussen M. D., Lin M. F., Santos M. A., Sakthikumar S., Munro C. A., et al. (2009). Evolution of pathogenicity and sexual reproduction in eight Candida genomes. Nature 459, 657–662. 10.1038/nature08064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow B. D., Linden J. R., Bliss J. M. (2012). Candida parapsilosis and the neonate: epidemiology, virulence and host defense in a unique patient setting. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 10, 935–946. 10.1586/eri.12.74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gácser A., Salomon S., Schäfer W. (2005). Direct transformation of a clinical isolate of Candida parapsilosis using a dominant selection marker. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 245, 117–121. 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gácser A., Trofa D., Schäfer W., Nosanchuk J. D. (2007). Targeted gene deletion in Candida parapsilosis demonstrates the role of secreted lipase in virulence. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 3049–3058. 10.1172/JCI32294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghannoum M. A. (2000). Potential role of phospholipases in virulence and fungal pathogenesis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13, 122–143, table of contents. 10.1128/CMR.13.1.122-143.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinea J. (2014). Global trends in the distribution of Candida species causing candidemia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20(Suppl 6), 5–10. 10.1111/1469-0691.12539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland L. M., Schröder M. S., Turner S. A., Taff H., Andes D., Grózer Z., et al. (2014). Comparative phenotypic analysis of the major fungal pathogens Candida parapsilosis and Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004365. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horváth P., Nosanchuk J. D., Hamari Z., Vágvölgyi C., Gácser A. (2012). The identification of gene duplication and the role of secreted aspartyl proteinase 1 in Candida parapsilosis virulence. J. Infect. Dis. 205, 923–933. 10.1093/infdis/jir873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hube B., Stehr F., Bossenz M., Mazur A., Kretschmar M., Schäfer W. (2000). Secreted lipases of Candida albicans: cloning, characterisation and expression analysis of a new gene family with at least ten members. Arch. Microbiol. 174, 362–374. 10.1007/s002030000218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ifrim D. C., Bain J. M., Reid D. M., Oosting M., Verschueren I., Gow N. A., et al. (2014). Role of Dectin-2 for host defense against systemic infection with Candida glabrata. Infect. Immun. 82, 1064–1073. 10.1128/IAI.01189-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffey S. F., Butler G. (2005). Phenotype switching affects biofilm formation by Candida parapsilosis. Microbiology (Reading Engl). 151, 1073–1081. 10.1099/mic.0.27739-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis L. E., Bain J. M., Lowes C., Gillespie C., Rudkin F. M., Gow N. A., et al. (2012). Stage specific assessment of Candida albicans phagocytosis by macrophages identifies cell wall composition and morphogenesis as key determinants. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002578. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis L. E., Bain J. M., Okai B., Gow N. A., Erwig L. P. (2013). Live-cell video microscopy of fungal pathogen phagocytosis. J. Vis. Exp. 71:e50196. 10.3791/50196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy I., Filkor K., Németh T., Hamari Z., Vágvölgyi C., Gácser A. (2011). In vitro interactions of Candida parapsilosis wild type and lipase deficient mutants with human monocyte derived dendritic cells. BMC Microbiol. 11:122. 10.1186/1471-2180-11-122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L. N., Gacser A., Nosanchuk J. D. (2011). Secreted lipases supply fatty acids for yeast growth in the absence of de novo fatty acid synthesis. Virulence 2, 538–541. 10.4161/viru.2.6.18244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosek J., Holesova Z., Kosa P., Gacser A., Tomaska L. (2009). Biology and genetics of the pathogenic yeast Candida parapsilosis. Curr. Genet. 55, 497–509. 10.1007/s00294-009-0268-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okai B., Lyall N., Gow N. A., Bain J. M., Erwig L. P. (2015). Rab14 regulates maturation of macrophage phagosomes containing the fungal pathogen Candida albicans and outcome of the host-pathogen interaction. Infect. Immun. 83, 1523–1535. 10.1128/IAI.02917-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pammi M., Holland L., Butler G., Gacser A., Bliss J. M. (2013). Candida parapsilosis is a significant neonatal pathogen: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 32, e206–e216. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182863a1c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryszcz L. P., Németh T., Gácser A., Gabaldón T. (2013). Unexpected genomic variability in clinical and environmental strains of the pathogenic yeast Candida parapsilosis. Genome Biol. Evol. 5, 2382–2392. 10.1093/gbe/evt185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quindos G. (2014). Epidemiology of candidaemia and invasive candidiasis. A changing face. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 31, 42–48. 10.1016/j.riam.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudkin F. M., Bain J. M., Walls C., Lewis L. E., Gow N. A., Erwig L. P. (2013). Altered dynamics of Candida albicans phagocytosis by macrophages and PMNs when both phagocyte subsets are present. MBio 4, e00810–e00813. 10.1128/mBio.00810-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller M., Borelli C., Korting H. C., Hube B. (2005). Hydrolytic enzymes as virulence factors of Candida albicans. Mycoses 48, 365–377. 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2005.01165.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva S., Henriques M., Hayes A., Oliveira R., Azeredo J., Williams D. W. (2011). Candida glabrata and Candida albicans co-infection of an in vitro oral epithelium. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 40, 421–427. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00981.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehr F., Felk A., Gacser A., Kretschmar M., Mähnss B., Neuber K., et al. (2004). Expression analysis of the Candida albicans lipase gene family during experimental infections and in patient samples. FEMS Yeast Res. 4, 401–408. 10.1016/S1567-1356(03)00205-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth A., Németh T., Csonka K., Horváth P., Vágvölgyi C., Vizler C., et al. (2014a). Secreted Candida parapsilosis lipase modulates the immune response of primary human macrophages. Virulence 5, 555–562. 10.4161/viru.28509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth R., Tóth A., Papp C., Jankovics F., Vágvölgyi C., Alonso M. F., et al. (2014b). Kinetic studies of Candida parapsilosis phagocytosis by macrophages and detection of intracellular survival mechanisms. Front. Microbiol. 5:633. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trofa D., Agovino M., Stehr F., Schäfer W., Rykunov D., Fiser A., et al. (2009). Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) reduces damage to reconstituted human tissues infected with Candida species by inhibiting extracellular fungal lipases. Microbes Infect. 11, 1131–1139. 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trofa D., Gácser A., Nosanchuk J. D. (2008). Candida parapsilosis, an emerging fungal pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21, 606–625. 10.1128/CMR.00013-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trofa D., Soghier L., Long C., Nosanchuk J. D., Gacser A., Goldman D. L. (2011). A rat model of neonatal candidiasis demonstrates the importance of lipases as virulence factors for Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis. Mycopathologia 172, 169–178. 10.1007/s11046-011-9429-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Sobue T., Thompson A., Xie Z., Poon K., Ricker A., et al. (2014). Streptococcal co-infection augments Candida pathogenicity by amplifying the mucosal inflammatory response. Cell. Microbiol. 16, 214–231. 10.1111/cmi.12216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.