Abstract

Objective

Low bone quality is a contributing factor to motor vehicle crash (MVC) injury. Quantification of occupant bone mineral density (BMD) is important from an injury causation standpoint. The first aim of this study was to validate a technique for measuring lumbar volumetric BMD (vBMD) from phantom-less computed tomography (CT) scans. The second aim was to apply the validated phantom-less technique to quantify lumbar vBMD in Crash Injury Research and Engineering Network (CIREN) occupants for correlation with age, fracture incidence, and osteopenia/osteoporosis diagnoses.

Methods

Quantitative CT (qCT) and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) were collected prospectively for 50 subjects and used to validate a technique to measure vBMD from 281 phantom-less CT scans of CIREN occupants. Hounsfield Unit (HU) measurements were collected from the L1-L5 vertebrae, right psoas major muscle, and anterior subcutaneous fat for all subjects and from three phantom ports with known mg/cc calcium hydroxyapatite values for the validation group. qCT calibration was accomplished using regressions between the phantom HU and mg/cc values to convert L1-L5 HU values to mg/cc. A phantom-less calibration technique was developed where the fat and muscle HU values were linearly regressed against fat (−69 mg/cc) and muscle (77 mg/cc) to establish a conversion for L1-L5 HU measurements to mg/cc. vBMD calculated from qCT versus the phantom-less method was compared for the 50 subjects to assess agreement and a mg/cc osteopenia threshold was established using DXA T-scores. CIREN HU measurements were converted to mg/cc using the phantom-less technique and the mg/cc osteopenia threshold was used to compare vBMD to age, fracture incidence, and osteopenia comorbidity classifications in CIREN.

Results

Linear regression of lumbar vBMD derived from the qCT versus phantom-less calibrations showed excellent agreement (R2=0.87, p=<0.0001). A 145 mg/cc threshold for osteopenia was established (sensitivity=1, specificity=0.57) and 44 CIREN occupants had vBMD below this threshold. Of these 44 occupants, 64% were not classified as osteopenic in CIREN, but vBMD suggested undiagnosed osteopenia. Age was negatively correlated with vBMD in both sexes (p=<0.0001) and CIREN occupants with less than 145 mg/cc vBMD sustained an average 1.7 additional rib/sternum fractures (p=0.036).

Conclusions

As lumbar vBMD was estimated from phantom-less CT scans with accuracy similar to qCT, the phantom-less technique can be broadly applied to both prospectively and retrospectively assess patient bone quality for research and clinical studies related to MVCs, falls, and aging.

Keywords: Bone quality, Computed tomography, ImageJ, Injury, Osteopenia, Phantom-less, Trauma

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 54 million Americans currently have osteoporosis and the incidence of osteoporosis is expected to increase as the population continues to age (National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2014). Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease characterized by low bone density and deterioration of bone microarchitecture with a consequent increase in fragility (World Health Organization, 2003). Thus, bone of decreased density and quality is the defining characteristic of osteoporosis and the mild variant of this is known as osteopenia (Licata, 2009; World Health Organization, 2003). Bone quality, an amalgamation of all factors that determine how well the skeleton can resist fracturing, is measured by tests of strength and fragility, bone thickness, biomarkers, and bone mineral density (BMD) (Bouxsein, 2003; Licata, 2009). BMD is a measure of bone density that reflects calcium and mineral content and is most commonly measured in the lumbar spine or femoral neck due to its ability to predict fragility fractures at these clinically meaningful sites (Looker, et al., 2012).

Areal BMD (aBMD) in g/cm2 is traditionally measured with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and used to diagnose osteopenia and osteoporosis from T-scores and Z-scores derived from comparative BMD means (World Health Organization, 2003). T-scores measure how much an individual’s BMD deviates from a 30-year-old adult average, while Z-scores measure how much an individual’s BMD deviates from the average BMD for their respective age, sex, race, and/or weight. T-scores where BMD is more than 1 standard deviation below the 30 year old adult average (T-score < −1) indicate osteopenia, while T-scores < −2.5 indicate osteoporosis. Despite DXA’s diagnostic utility, more than half of all fractures occur in persons without osteoporosis (defined by aBMD), indicating that aBMD alone does not sufficiently quantify future fracture risk (Nguyen, et al., 2007).

Volumetric BMD (vBMD) obtained with quantitative computed tomography (qCT) is increasingly used to complement DXA-acquired aBMD estimates (Engelke, et al., 2013). qCT uses a scanned calibration phantom to transform attenuation measured in Hounsfield Units (HU) into known mg/cc calcium hydroxyapatite (CaHA) values (Link, et al., 2014). qCT measurement of vBMD is less dependent on bone size than DXA and may be used to selectively measure trabecular or cortical bone that are indistinguishable by DXA (Lenchik, et al., 2004; Link, et al., 2014; Mueller, et al., 2011). Furthermore, qCT allows for more accurate identification and exclusion of vertebral fractures than DXA, and is less influenced by arthritic changes, calcifications, or adipose tissue (Lenchik, et al., 2004; Link, et al., 2014; Mueller, et al., 2011; Yu, et al., 2014). BMD measurement from phantom-less clinical CT scans would increase the utility of thoracic or abdominal CT scans for osteopenia/osteoporosis screening. Lumbar BMD measurement from phantom-less CT has been explored in previous studies (Buckens, et al., 2015; Lee, et al., 2015; Pickhardt, et al., 2011; Pickhardt, et al., 2013). The fundamental difference between phantom-less and phantom-based (qCT) BMD measurement from CT is the calibration procedure (Mueller, et al., 2011). Rather than calibrating from CaHA phantom ports, phantom-less calibration utilizes measurements from regions of interests (ROIs) in the musculature and subcutaneous fat (Pickhardt, et al., 2011).

Low bone quality is a known contributing factor to high-trauma fractures (e.g. those resulting from MVCs and falls from greater than standing height) (Mackey, et al., 2007). Thus, quantification of an occupant's BMD is important from an injury causation standpoint. Since most CT scans done for a traumatized patient do not contain a phantom, the first aim of this study was to validate a technique for measuring lumbar vBMD from phantom-less clinical CT scans. The second aim was to apply the validated technique to quantify lumbar vBMD for 281 seriously injured Crash Injury Research and Engineering Network (CIREN) occupants from phantom-less clinical CT scans and to correlate vBMD to age, fracture incidence, and osteopenia/osteoporosis diagnoses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Validation of Bone Mineral Density Measurement Technique

DXA, which is commonly used to diagnose osteopenia and osteoporosis, and qCT scans were collected prospectively for 50 subjects and used to validate a technique to measure vBMD from phantom-less CT scans. Fifty subjects (33 females and 17 males) between the ages of 60–76 were recruited as part of the Cooperative Lifestyle Intervention Program (CLIP-II), a study of older, overweight, and obese adults with cardiovascular disease or metabolic syndrome (R18 HL076441). Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained for the CLIP-II study. aBMD was determined in the CLIP-II subjects by supine DXA scans of the anterior-posterior L1-L4 spine (iDXA, GE Medical Systems, Madison, WI). Helical qCT scans of the lumbar spine (L1-L5) were acquired from the CLIP-II subjects on a 64-slice CT scanner (LightSpeed VCT, General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) and a 4-port In Table bone mineral phantom (Image Analysis, Columbia, KY) was imaged in every scan. The CT scanning protocol involved a scan field of view (SFOV) of 50, 120 KVp, 250 mA, 2.5 mm helical with a pitch of 1.375:1, a 0.8 second gantry speed, standard reconstruction, with secondary reconstruction at 0.625 mm thick using a bone algorithm.

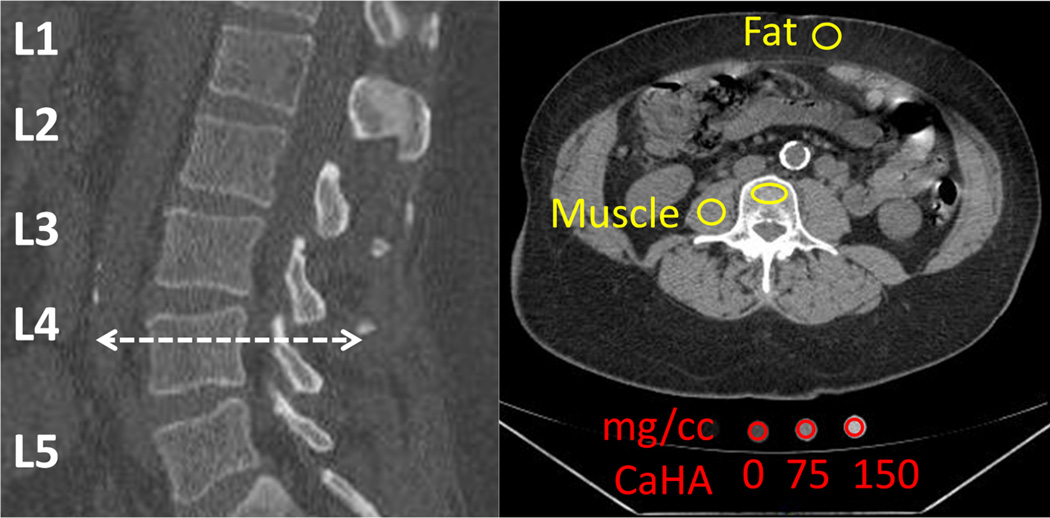

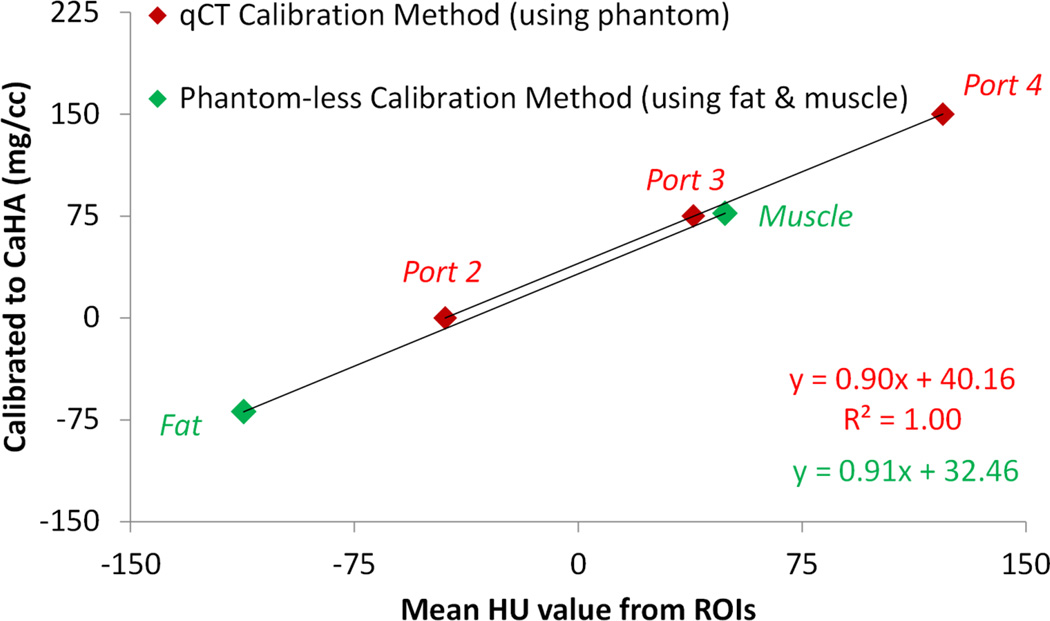

Mean Hounsfield Unit (HU) values were collected in ImageJ (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) from ROIs on the L1-L5 vertebrae, right psoas major muscle, and anterior subcutaneous fat for all CLIP-II subjects and from three phantom ports with known mg/cc CaHA values (Figure 1). The window center level was set to 125 and window width was set to 540 in each scan. Lumbar ROIs were placed to be centrally located within the trabecular bone of each vertebra and a consistent ROI size was used for all vertebral levels (L1-L5). ROIs were placed to avoid metallic or CT streaks, surgical artifacts, or bright calcifications. ROIs for the muscle, fat, and phantom ports were placed as shown in Figure 1. qCT calibration was accomplished using linear regressions between the mean HU values collected from the phantom ports and the known mg/cc values (0, 75, and 150 mg/cc CaHA) to convert L1-L5 HU values to mg/cc for the 50 CLIP-II subjects (Figure 2 and Appendix). A phantom-less calibration technique was developed where the fat and muscle HU values were linearly regressed against ground truth values for fat (−69 mg/cc) and muscle (77 mg/cc) to establish a conversion for L1-L5 HU measurements to mg/cc (Eqs. (1) and (2), Figure 2, and Appendix). The ground truth values for fat and muscle were derived from the CLIP-II subject data by using the phantom calibration method (Figure 2) to convert the fat and muscle mean HU values obtained from the ROIs to mg/cc. Then, the fat and muscle mg/cc measures were averaged across all 50 CLIP-II subjects to compute the ground truth values of −69 mg/cc for fat and 77 mg/cc for muscle.

| (1) |

| (2) |

where HUFat and HUMuscle are the mean HU values obtained from the ROIs placed on the subcutaneous fat and psoas major muscle, respectively. The system of equations, Eqs. (1) and (2), are solved to compute the slope (β1) and y-intercept (β0,) of the linear regression equation to calibrate HU values using the phantom-less technique.

Figure 1.

Mean HU values collected from the illustrated ROIs on the L4 vertebra, right psoas major muscle, anterior subcutaneous fat, and three phantom ports. Mean HU values were also collected from L1, L2, L3, and L5 vertebrae (not shown).

Figure 2.

Example for one CLIP-II subject of the equations used to convert mean HU values from the ROIs to mg/cc vBMD. As shown, qCT calibration using a phantom and phantom-less calibration using fat and muscle ROI measurements yielded similar equations to convert from HU values to mg/cc vBMD. Equations for all 50 CLIP-II subjects are provided in the Appendix.

Mean lumbar vBMD was computed for each subject by averaging the mg/cc vBMD measurements from five vertebrae (L1-L5). Mean lumbar vBMD calculated with the two techniques (qCT versus phantom-less) was compared for the 50 subjects to assess agreement using simple linear regression. The statistical significance of this linear regression model was evaluated with an overall model F-test to test whether the model explains a significant portion of the variation in the data. A paired t-test was conducted to compare differences in the slopes of the calibration equations from the qCT technique versus the phantom-less technique. A paired t-test was also used to compare differences in the y-intercepts of the calibration equations from the qCT technique versus the phantom-less technique. The mg/cc threshold that best discriminated for osteopenia in the 50 CLIP-II subjects was established by performing a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis using DXA-derived T-scores of the lumbar spine to distinguish corresponding mg/cc values as osteopenic or not. The ROC analysis results were used to select the threshold associated with the maximum specificity when sensitivity was equal to 100%. Further validation of the threshold determined with DXA-derived T-scores was performed through comparison with reported thresholds for osteopenia in the literature (American College of Radiology, 2014; Pickhardt, et al., 2013) and commercial qCT software (Image Analysis software, N-Vivo version 1.20, Columbia, KY).

Bone Mineral Density Measurement in CIREN Occupants

vBMD was measured in seriously injured MVC occupants enrolled in the CIREN study at Wake Forest University School of Medicine between 2006 to 2014. Through the CIREN program, detailed vehicle, crash, and medical information were collected for each subject and presented at a multidisciplinary case review in which engineers and physicians assessed the crash mechanics, biomechanics, and clinical aspects of the occupant’s injuries (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2010). IRB approval was obtained for the CIREN study. BMD analyses focused on 281 CIREN occupants (109 males and 172 females) ranging in age from 16 to 88 years that received an abdominal CT scan as part of their hospital course following a MVC. CIREN cases analyzed included frontal, near side, and far side crashes with varying crash and occupant characteristics. Each CIREN CT scan was reconstructed to 0.625 or 1.25 mm slice thickness and no phantom was present in the scan. The vBMD measurement technique previously described was applied to the CIREN CT scans to collect mean HU values from ROIs on the L1–L5 vertebrae, right psoas major muscle, and anterior subcutaneous fat. Fractures of the lumbar vertebral body were present in 2.1% of the vertebrae analyzed and the ROI size was adjusted in these cases to avoid the fractured area. Using Eqs. (1) and (2), the fat and muscle HU values were linearly regressed against ground truth values for fat (−69 mg/cc) and muscle (77 mg/cc) to establish a conversion for the L1–L5 HU measurements to mg/cc. Mean lumbar vBMD was computed for each CIREN subject by averaging the mg/cc vBMD measurements from five vertebrae (L1-L5). The established mg/cc threshold for osteopenia was used to compare CT-derived vBMD measures to osteopenia/osteoporosis comorbidity classifications in the CIREN database which are determined from documented physician diagnosis. Simple linear regression of mean lumbar vBMD versus height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) of the CIREN subjects was performed. For each sex, simple linear regression of mean lumbar vBMD versus age was performed. Low lumbar spine BMD has been correlated with increased rib fracture incidence and risk, particularly in women (Kroger, et al., 1995; Wuermser, et al., 2011). Thus, a multivariate linear regression model controlling for change in vehicle velocity (delta-v) and the subject’s dichotomous classification of vBMD using the established mg/cc osteopenia threshold was fit to the CIREN data to predict rib and sternum fracture incidence. Statistical significance of the simple linear regression models and the multivariate linear regression model was evaluated with an overall model F-test to test whether the model explained a significant portion of the variation in the data.

Currently, there are no consensus standards for assigning diagnostic categories (normal, osteopenia, versus osteoporosis) based on qCT spine BMD measurements (American College of Radiology, 2014). The American College of Radiology established a suggested 120 mg/cc osteopenia threshold that results in approximately the same proportion of the population being assigned to an osteopenia category based on qCT spine T-scores as would be assigned based on qCT hip T-scores. Pickhardt et al. (2013) used a 1,800 patient study of paired DXA and CT BMD measurements to establish a high sensitivity threshold (148 mg/cc), balanced sensitivity/specificity threshold (168 mg/cc), and a high specificity threshold (193 mg/cc) for osteopenia (Pickhardt, et al., 2013). Image Analysis software (N-Vivo version 1.20, Columbia, KY) utilizes a 150 mg/cc threshold for osteopenia. The aforementioned osteopenia thresholds were investigated to produce a truth table comparing occupants whose vBMD measurements exceeded particular mg/cc thresholds to osteopenia/osteoporosis comorbidities documented in CIREN.

RESULTS

Validation of Bone Mineral Density Measurement Technique

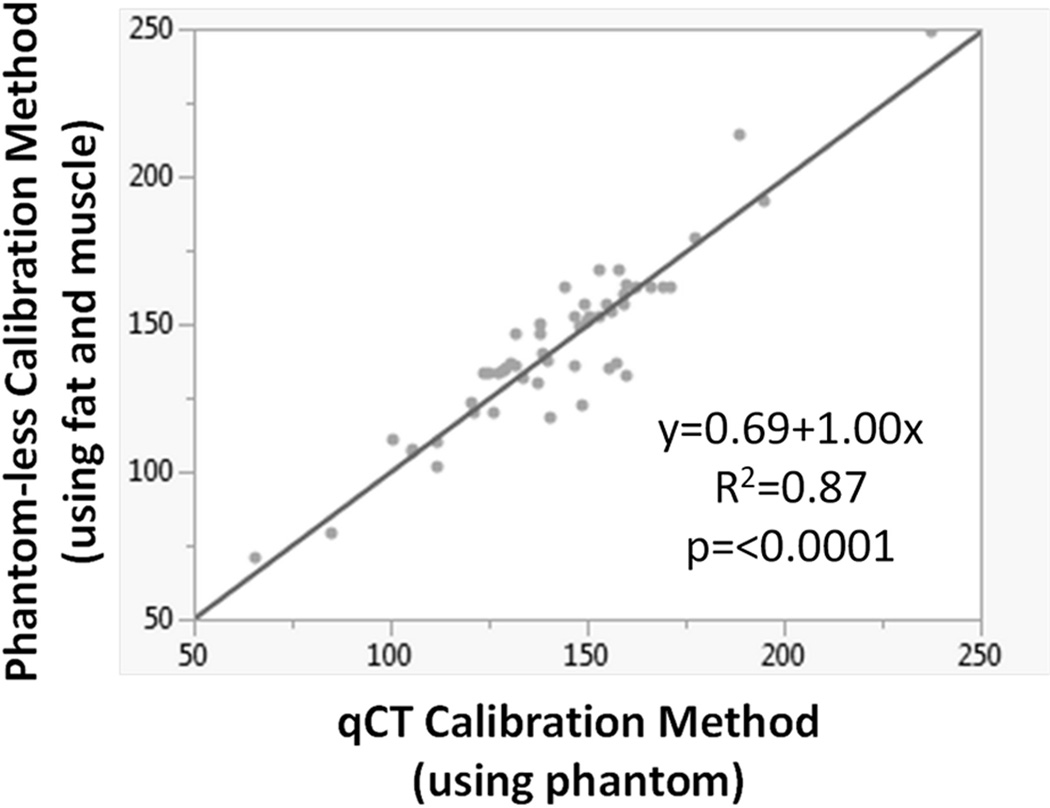

A highly significant linear regression relationship between the mean lumbar vBMD mg/cc values was achieved when comparing the qCT and phantom-less calibrations (Figure 3). This regression indicated excellent agreement between the lumbar vBMD mg/cc values obtained with the two calibration techniques (R2=0.87, p=<0.0001). A paired t-test revealed no statistically significant differences in the slopes (mean difference=−0.004, p=0.65) or y-intercepts (mean difference=0.641, p=0.56) between the qCT and phantom-less calibration equations. These results indicate that the phantom-less technique of using fat and muscle ROI measures closely replicates qCT calibration methods that require a phantom in the CT scan. DXA-derived T-scores for the L1–L4 vertebrae indicated normal bone quality in 42 subjects (14 males, 28 females), osteopenia in 7 subjects (2 males, 5 females), and osteoporosis in one male subject. The ROC analysis using L1–L4 T-scores calculated from DXA revealed a 145 mg/cc lumbar vBMD threshold best discriminated for osteopenia in these 50 CLIP-II subjects. The 145 mg/cc threshold maximized sensitivity (sensitivity=1) and resulted in no false negatives, meaning that all 8 subjects with T-scores less than −1 (osteopenia/osteoporosis diagnoses) had CT-derived lumbar vBMD measures below 145 mg/cc. Specificity associated with the 145 mg/cc threshold was 0.57. CT-derived lumbar vBMD measures among the 42 subjects with T-scores greater than or equal to −1 were greater than 145 mg/cc for 24 subjects (true negatives) and less than 145 mg/cc for 18 subjects.

Figure 3.

Excellent agreement in mean lumbar vBMD (mg/cc CaHA) was observed for the 50 CLIP-II subjects when comparing linear regression of vBMD measured using the qCT calibration method (phantom calibration) versus the phantom-less calibration method (fat and muscle calibration).

Bone Mineral Density Measurement in CIREN Occupants

Table 1 reports the sex distribution and the mean, standard deviation, and range of the ages, vBMD, and delta-v for the occupants with vBMD less than 145 mg/cc versus the occupants with vBMD of 145 mg/cc or greater. Twenty-nine CIREN occupants (10%) had a comorbidity of osteopenia or osteoporosis documented in the CIREN database which was determined based on documented physician diagnosis, while the remaining 252 occupants had no documented comorbidity related to bone quality. Forty-four (16%) of the CIREN occupants (28 females, 16 males) had vBMD measures below the 145 mg/cc threshold for osteopenia. Of these 44 occupants, 28 (64%) had no documented osteopenia/osteoporosis comorbidity in the CIREN database, but vBMD measures suggested undiagnosed osteopenia. Occupants are only documented with osteopenia/osteoporosis in CIREN if their medical record data (i.e. DXA) indicates osteopenia/osteoporosis, but often the presence of osteopenia/osteoporosis is unknown if the occupant has not had previous DXA evaluation. Of the 29 occupants with an osteopenia/osteoporosis comorbidity in the CIREN database, 13 (45%) had normal vBMD measures (>=145 mg/cc).

Table 1.

Comparison of the mean, standard deviation, and range of the ages, vBMD, and delta-v and the proportion of males and females for CIREN occupants with vBMD less than 145 mg/cc versus CIREN occupants with vBMD of 145 mg/cc or greater.

| Measure | CIREN occupants with vBMD < 145 mg/cc |

CIREN occupants with vBMD >= 145 mg/cc |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean |

St. Dev. |

Range | Mean |

St. Dev. |

Range | |

| Age (yrs) | 69 | 11 | 40–86 | 43 | 18 | 16–88 |

| vBMD (mg/cc) | 127.9 | 13.3 | 97.2–144.0 | 215.1 | 43.2 | 145.6–365.2 |

| Delta-v (km/h) | 33.1 | 15.2 | 11–79 | 41.9 | 18.9 | 11–116 |

| Sex | 36% males, 64% females | 39% males, 61% females | ||||

The CIREN occupants with vBMD below 145 mg/cc sustained an average 1.7 additional rib and sternum fractures compared to occupants with 145 mg/cc or greater vBMD (5.2 versus 3.5 fractures, p=0.036). Of the occupants with no documented bone quality comorbidity, those with less than 145 mg/cc vBMD sustained a higher number of rib/sternum fractures (4.1 versus 3.4 fractures), which further supports the notion of undiagnosed osteopenia in the occupants with low vBMD. Of the occupants with a vBMD of 145 mg/cc or greater, those classified as osteopenic in the CIREN database had a higher number of rib/sternum fractures (5.5 versus 3.4 fractures).

A multivariate linear regression model controlling for delta-v and the dichotomous classification of vBMD (<145 versus >=145 mg/cc) was fit to the CIREN data to predict the number of rib and sternum fractures (p=0.038). As Eq. (3) shows, the effect of having a vBMD less than 145 mg/cc results in an equivalent increase in the number of rib and sternum fractures as a 39 km/h change in delta-v (computed from 1.18/0.03). As an example, an occupant with a vBMD of 145 mg/cc or greater involved in a 49km/h delta-v crash is predicted to have an equivalent number of rib/sternum fractures as an occupant with a vBMD less than 145 mg/cc involved in a 10 km/h delta-v crash.

| (3) |

where DV is the delta-v in km/h and vBMD145 = 1 when the subject’s

The incidence of lumbar vertebral body fractures among the CIREN occupants was low, with only 29 lumbar vertebral body fractures occurring in 24 unique CIREN occupants. Thus, less than 2.1% of the lumbar vertebrae analyzed sustained a vertebral body fracture. Due to the low incidence of this injury in the CIREN sample, comparison of lumbar vertebral body fracture incidence to vBMD, crash, and occupant characteristics was limited.

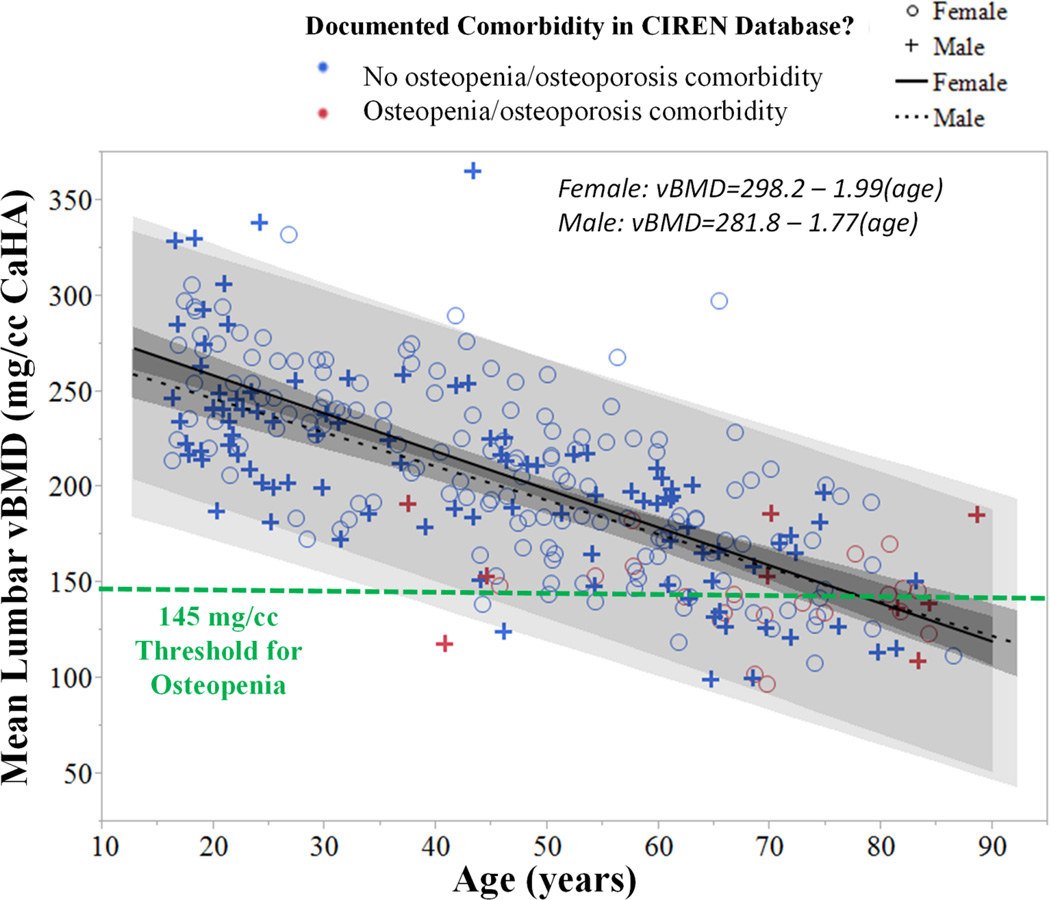

Height, weight, and BMI were poorly correlated to lumbar vBMD (R2 = 0.003, 0.020, and 0.013, respectively), which is in contrast to positive correlations between BMD and weight/BMI that have been reported in larger studies (Felson, et al., 1993; Reid, 2002). The 281 CIREN occupants that were analyzed ranged in age from 16–88 years with a median age of 47 years. As Figure 4 shows, age was negatively correlated with vBMD as expected in both sexes (both p=<0.0001). vBMD declined more rapidly in females compared to males, and this trend can be observed in Figure 4 by the steeper decline in vBMD from young age (16 years) to elderly age (65 years) in females. Some occupants with particularly low vBMD were documented as osteopenic in CIREN, such as a 40 year old male who was paraplegic prior to the MVC with a vBMD of 118 mg/cc. Other occupants, including a 44 year old female and 46 year old male that sustained a multitude of fractures, had low vBMD with no documented osteopenia comorbidity in CIREN. The 44 year old female had a vBMD of 139 mg/cc and sustained six rib fractures, five lumbar transverse process fractures, and an orbital wall blowout fracture. This occupant was a 77.1 kg, 157 cm unbelted driver involved in a near side tree impact with no airbags deployed and an out of scope delta-v and principal direction of force (PDOF). Thus, other crash and occupant-related factors likely also contributed to this occupant’s fracture patterns. The 46 year old male had a vBMD of 125 mg/cc and sustained four rib fractures, a lumbar vertebral body compression fracture, and a bimalleolar fracture. This occupant was a 100 kg, 185 cm belted driver with frontal airbag deployment who was involved in a frontal impact to a light truck at 47 km/h delta-v. Along with low lumbar vBMD, other crash- and occupant-related factors likely also contributed to this occupant’s fracture patterns.

Figure 4.

Mean lumbar vBMD measurements for 281 CIREN occupants were negatively correlated with age in both sexes (both p<0.0001). Comorbidities documented in the CIREN database are indicated by the color legend. vBMD measurements for 44 CIREN occupants were below the 145 mg/cc threshold for osteopenia. Confidence of fit and confidence of prediction is illustrated for the trend lines by gray shading.

The truth table comparing occupants whose vBMD measurements exceeded particular mg/cc thresholds to osteopenia/osteoporosis comorbidities documented in CIREN is provided in Table 2. The high sensitivity 148 mg/cc threshold reported by Pickhardt et al. (2013) as well as the 150 mg/cc threshold used in the BMD-estimation software package, Image Analysis (N-Vivo version 1.20, Columbia, KY), were nearly identical to the 145 mg/cc threshold derived in the validation phase of this study. The American College of Radiology threshold, which is much lower (120 mg/cc), would indicate possible misclassification of 25 (86%) of the occupants documented as osteopenic in CIREN based on physician diagnosis (American College of Radiology, 2014). On the other hand, the Pickhardt et al. (2013) balanced sensitivity/specificity 168 mg/cc and high specificity 193 mg/cc thresholds may over-predict osteopenia, suggesting osteopenia in 22% and 39% of the occupants with no documented bone quality comorbidities, respectively. These findings further support the validity of a vBMD threshold near 145 mg/cc for identifying subjects with osteopenia in this dataset.

Table 2.

Truth table comparing vBMD measurements in the 281 CIREN occupants to osteopenia/osteoporosis comorbidities documented in the CIREN database for several different mg/cc osteopenia thresholds. Linear correlation between mean lumbar HU and vBMD in mg/cc in the 281 CIREN occupants was used to convert the Pickhardt et al. (2013) HU thresholds to mg/cc (vBMD=36.96+0.82(HU), R2=0.89). True positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), false negatives (FN), sensitivity, and specificity are reported. Occupants with vBMD < the mg/cc threshold are classified as TP if they have an osteopenia/osteoporosis comorbidity in CIREN and FP otherwise. Occupants with vBMD >= the mg/cc threshold are classified as FN if they have an osteopenia/osteoporosis comorbidity in CIREN and TN otherwise.

| Reference | Threshold (mg/cc) |

vBMD < Threshold |

vBMD >= Threshold |

Sensitivity/ Specificity |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | FP | TN | FN | |||

| American College of Radiology (American College of Radiology, 2014) | 120 | 4 | 7 | 245 | 25 | 0.36 / 0.91 |

| Current Study | 145 | 16 | 28 | 224 | 13 | 0.36 / 0.95 |

| Pickhardt et al.–135 HU high sensitivity threshold (Pickhardt, et al., 2013) | 148 | 18 | 30 | 222 | 11 | 0.38 / 0.95 |

| Image Analysis software (N-Vivo version 1.20) | 150 | 19 | 35 | 217 | 10 | 0.35 / 0.96 |

| Pickhardt et al.–160 HU balanced sensitivity/specificity threshold (Pickhardt, et al., 2013) | 168 | 24 | 55 | 197 | 5 | 0.30 / 0.98 |

| Pickhardt et al.–190 HU high specificity threshold (Pickhardt, et al., 2013) | 193 | 29 | 98 | 154 | 0 | 0.23 / 1.00 |

DISCUSSION

A phantom-less vBMD technique using fat and muscle measurements to calibrate HU measurements collected at the L1–L5 vertebrae was validated in this study using a cohort of 50 subjects with paired DXA and qCT scans. The phantom-less calibration technique yielded similar accuracy to qCT and this method of calibration is supported by other BMD studies (Pickhardt, et al., 2011). A 145 mg/cc threshold for osteopenia with high sensitivity was defined based on DXA T-scores from 50 subjects, and this threshold was similar to other osteopenia thresholds reported in BMD software (Image Analysis, N-Vivo version 1.20, Columbia, KY) and the high sensitivity threshold reported in a large study of paired DXA and CT BMD measurements from over 1,800 patients (Pickhardt, et al., 2013). Although three thresholds (high sensitivity, balanced sensitivity/specificity, and high specificity) were reported by Pickhardt et al. (2013), the high sensitivity threshold of 148 mg/cc is the most appropriate threshold to compare to, as the 145 mg/cc threshold was also chosen to maximize sensitivity. The American College of Radiology’s 120 mg/cc threshold for osteopenia is much lower, possibly because it is determined based on diagnostic categories used for hip BMD measurements as opposed to being developed with spine BMD data (American College of Radiology, 2014).

As has been reported in other studies, variation in vBMD measures was observed between vertebral levels of the lumbar spine (Lee, et al., 2015; Pickhardt, et al., 2011; Pickhardt, et al., 2013). On a per subject-basis, the average difference between the vBMD measure at a single lumbar vertebra was only 0.7–4.2 mg/cc different from the mean of the vBMD measurements from L1-L5. vBMD was 4.0 (L1), 3.7 (L2), −2.8 (L3), −4.2 (L4) and −0.7 (L5) mg/cc different from the mean vBMD obtained from L1-L5. Mean vBMD from L1-L5 was also highly correlated (R2: 0.96–0.97) with vBMD at each lumbar level. Since the validation portion of this study (CLIP-II subjects) focused on the average DXA and vBMD measures from multiple lumbar vertebra levels, averaging the L1-L5 vBMD measures for the CIREN subject analysis was thought to be most appropriate for comparison purposes.

Lumbar BMD in the CIREN occupants decreased with age in both sexes, with a more rapid decline in females compared to males, which supports the findings of other studies (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012; Samelson, et al., 2012). In the CIREN occupants, vBMD less than 145 mg/cc was associated with a significant increase in the number of rib and sternum fractures sustained in MVCs even when controlling for delta-v. Since aging is correlated with decreased BMD and increased thoracic morbidity and mortality, elderly occupants are particularly at risk (Stitzel, et al., 2010). Elderly patients with thoracic injury present with more comorbidities, develop more complications, and require more ventilator days, intensive care unit (ICU) days, and longer hospital stays (Finelli, et al., 1989; Hanna, 2009; Holcomb, et al., 2003; Perdue, et al., 1998; Shorr, et al., 1989). Complications from thoracic injury include atelectasis, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and respiratory failure that often result from hypoventilation due to rib fractures or underlying pulmonary contusion. Elderly patients with rib fractures have two to five times the mortality risk of younger patients and each additional rib fracture results in a 19% increase in mortality and 27% increase in pneumonia (Bergeron, et al., 2003; Bulger, et al., 2000; Kent, et al., 2008; Stawicki, et al., 2004).

The 145 mg/cc threshold designated 28 CIREN occupants with possible undiagnosed osteopenia. The false discovery rate suggests 64% of those classified as osteopenic based on vBMD are undiagnosed in CIREN. The positive predictive value is thus 36%, corresponding to the proportion of those classified as osteopenic based on vBMD that were correctly classified in the CIREN database. The poor correlation between vBMD measures and documented comorbidities in CIREN highlights possible underreporting of osteopenia/osteoporosis in CIREN since the method of vBMD measurement demonstrated reasonable accuracy. Underreporting is entirely possible and somewhat expected since all CIREN occupants do not receive tests for BMD (i.e. DXA), and documented physician diagnosis is required to document comorbidities in CIREN.

This technique, developed and validated to measure lumbar vBMD from phantom-less clinical CT scans, can be broadly applied across the United States to classify osteopenia in patients sustaining all types of trauma (i.e., MVCs, falls, sports-related injuries). It is routine for trauma centers to perform CT scans on all trauma patients. One of the new requirements for hospitals to get full reimbursement in the United States is to ensure that patients with fragility fractures get appropriate follow up (including DXA), and this technique could potentially be used in place of DXA in the future, resulting in decreased healthcare costs and the elimination of additional radiation exposure for patients (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2015).

As the majority of CIREN occupants have a CT scan available for measuring vBMD, this study provides a valuable quantitative tool for CIREN center case reviews in which engineers and physicians determine injury causation from vehicle, crash, and medical evidence. As part of the CIREN study, involved physical components within the vehicle (i.e., seat belt, B-pillar, airbag) are attributed to each occupant injury and comorbidities such as osteopenia and osteoporosis that may have contributed to injury are documented. Medical record data indicating osteopenia/osteoporosis (i.e. DXA) is available in some cases, but often the presence of osteopenia/osteoporosis is unknown if the occupant has not had previous DXA evaluation. Thus, the addition of vBMD data in these case reviews would provide quantitatively-based determinations of bone quality to substantiate decreased BMD or elderly age as a contributing factor to injury. With the incidence of MVC-related thoracolumbar spine injuries increasing over time, detection of reduced lumbar vBMD in CIREN MVC occupants may become even more important (Doud, et al., 2015; Pintar, et al., 2012). Estimation of lumbar vBMD in MVC occupants could help determine the relative contributions of bone quality versus other factors (i.e., vehicle seat design, crash characteristics) to thoracolumbar fracture incidence.

Limitations

The phantom-less CT analysis of CIREN occupants was retrospective, and vBMD measures may be subject to error due to differences in CT scanner calibrations as scans were collected over the course of a nine year period (2006–2014). However, error is estimated to be minimal as CT technicians performed routine calibration scans of an air phantom at least daily and a water phantom at least yearly. The average reported error in yearly CT calibration reports from the 2006–2014 time period was only 2.73 +/− 4.01 HU. A variation of 3 HU is substantially less than the variation in mg/cc or HU thresholds for osteopenia reported in the literature (American College of Radiology, 2014; Pickhardt, et al., 2013). The majority (97%) of the CIREN scans analyzed were contrast-enhanced which may lead to underestimation of osteopenia/osteoporosis compared to non-contrast CT (Pompe, et al., 2015). Calibration with fat and muscle measures collected from the same scan may adjust for the effect of contrast, but further investigation is warranted to evaluate this theory.

CIREN CT scans were collected on an emergency department CT scanner as part of the clinical course of each trauma patient, whereas the CLIP-II CT scans were collected prospectively under controlled conditions on a research CT scanner. Variation in the CT scanner used and scanning protocols between the CIREN and CLIP-II subjects presents a limitation and may affect the study results and conclusions. The current study illustrates the utility of applying a vBMD measurement technique to retrospective CT scan data and future studies are needed to examine the effects of different scanners and settings on measured vBMD.

vBMD measurements were collected by three different researchers which could introduce inter-subject variability. However, inter-subject variability was quantified by having all three users collect vBMD from all 50 CLIP-II subjects and was found to be low, varying on average 1.48 +/− 9.47 mg/cc.

The smaller sample size and characteristics of the elderly, overweight, and comorbid CLIP-II cohort used to validate the 145 mg/cc osteopenia threshold may limit its prediction sensitivity. The 145 mg/cc threshold that discriminates best for the CLIP-II cohort may be biased due to overrepresentation of subjects with osteopenia/osteoporosis or muscle with fat infiltration (Nakagawa, et al., 2007). However, other studies have reported similar thresholds of 148 and 150 mg/cc for osteopenia which is encouraging evidence to support the 145 mg/cc threshold derived in this study (Table 2).

CIREN is a convenience sample of seriously injured MVC occupants which may introduce bias in the correlations derived. Although vBMD measurements were collected from hundreds of CIREN occupants, these sample sizes and the variation in crash and occupant characteristics among the study population limit the ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding correlation of vBMD with age, BMI, sex and fracture incidence in MVC occupants. For instance, crash mode, impacting vehicle size, and intrusion affect rib/sternum fracture patterns, however controlling for all of these variables was beyond the scope of the study given the limited sample size. The multivariate model controlled for crash severity using delta-v, but more in depth studies are needed to tease out the effect of other factors beyond age, delta-v, and vBMD on rib/sternum fracture incidence.

Future Work and Applications

In future studies, a phantom could be included in the CT scanner within the emergency department so that vBMD could be quantified in trauma patients using qCT methods. Alternatively, more frequent calibrations with the air and water phantoms could be done to improve the accuracy of HU measures obtained from phantom-less CT scans. However, only minimal improvement in accuracy would be expected and the expenditure of additional resources (i.e. cost of the phantom and installation, technician training, technician and scan time) may not be feasible across different CIREN centers and other trauma centers. At present, all CIREN centers can use this phantom-less technique in open source software to quantify vBMD from CT scans of occupants prior to case reviews. In future studies, we aim to apply this vBMD technique to CT scans obtained from other CIREN centers, including CT scans obtained from different scanners and different hospitals. As lumbar vBMD was estimated from phantom-less CT scans with accuracy similar to qCT, the phantom-less technique can be broadly applied to both prospectively and retrospectively assess patient bone quality for research and clinical studies related to MVCs, falls, aging, and other applications.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Divya Jain, Samantha Schoell, and Avery Wilson for their assistance with data collection and analysis. Funding was provided by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration under Cooperative Agreement Number DTN22-10-H-00294. This work was also partially supported by the National Institutes of Health (R18 HL076441 and P30-AG21332) as well as the Wake Forest School of Medicine Translational Science Institute and Wake Forest University Translational Science Center. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the sponsors.

Contributor Information

Ashley A. Weaver, Email: asweaver@wakehealth.edu.

Kristen M. Beavers, Email: beaverkm@wfu.edu.

R. Caresse Hightower, Email: rhightow@wakehealth.edu.

Sarah K. Lynch, Email: salynch@wakehealth.edu.

Anna N. Miller, Email: anmiller@wakehealth.edu.

Joel D. Stitzel, Email: jstitzel@wakehealth.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.American College of Radiology. ACR–SPR–SSR Practice Parameter for the Performance of Quantitative Computed Tomography (QCT) Bone Densitometry. Resolution 32-2013, Amended 2014 (Resolution 39) 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergeron E, Lavoie A, Clas D, et al. Elderly Trauma Patients with Rib Fractures Are at Greater Risk of Death and Pneumonia. J Trauma. 2003;54(3):478–485. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000037095.83469.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouxsein ML. Bone quality: where do we go from here? Osteoporos Int. 2003 Sep;14(Suppl 5):S118–S127. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1489-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckens CF, Dijkhuis G, de Keizer B, Verhaar HJ, de Jong PA. Opportunistic screening for osteoporosis on routine computed tomography? An external validation study. Eur Radiol. 2015 Jan 17; doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3584-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bulger EMMD, Arneson MAMD, Mock CNMDP, Jurkovich GJMD. Rib Fractures in the Elderly. Journal of Trauma-Injury Infection & Critical Care. 2000;48(6):1040–1047. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200006000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lumbar Spine and Proximal Femur Bone Mineral Density, Bone Mineral Content, and Bone Area: United States, 2005–2008. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Physician Quality Reporting System. 2015 http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/MeasuresCodes.html.

- 8.Doud AN, Weaver AA, Talton JW, et al. Has the incidence of thoracolumbar spine injuries increased in the United States from 1998 to 2011? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015 Jan;473(1):297–304. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3870-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelke K, Libanati C, Fuerst T, Zysset P, Genant HK. Advanced CT based in vivo methods for the assessment of bone density, structure, and strength. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2013 Sep;11(3):246–255. doi: 10.1007/s11914-013-0147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felson DT, Zhang Y, Hannan MT, Anderson JJ. Effects of weight and body mass index on bone mineral density in men and women: the Framingham study. J Bone Miner Res. 1993 May;8(5):567–573. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finelli FC, Jonsson J, Champion HR, Morelli S, Fouty WJ. A Case Control Study for Major Trauma in Geriatric Patients. J Trauma. 1989;29(5):541–548. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198905000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanna R, Hershman, Lawrence . Evaluation of Thoracic Injuries Among Older Motor Vehicle Occupants. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2009. Mar, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holcomb JB, McMullin NR, Kozar RA, Lygas MH, Moore FA. Morbidity from rib fractures increases after age 45. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2003 Apr;196(4):549–555. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01894-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kent R, Woods W, Bostrom O. Fatality risk and the presence of rib fractures. Ann Adv Automot Med. 2008 Oct;52:73–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroger H, Huopio J, Honkanen R, et al. Prediction of fracture risk using axial bone mineral density in a perimenopausal population: a prospective study. J Bone Miner Res. 1995 Feb;10(2):302–306. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SY, Kwon SS, Kim HS, et al. Reliability and validity of lower extremity computed tomography as a screening tool for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2015 Apr;26(4):1387–1394. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-3013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenchik L, Shi R, Register TC, Beck SR, Langefeld CD, Carr JJ. Measurement of trabecular bone mineral density in the thoracic spine using cardiac gated quantitative computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004 Jan-Feb;28(1):134–139. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200401000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Licata A. Bone density vs bone quality: what's a clinician to do? Cleve Clin J Med. 2009 Jun;76(6):331–336. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76a.08041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Link TM, Lang TF. Axial QCT: clinical applications and new developments. J Clin Densitom. 2014 Oct-Dec;17(4):438–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2014.04.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Looker AC, Borrud LG, Hughes JP, Fan B, Shepherd JA, Melton LJ., 3rd Lumbar spine and proximal femur bone mineral density, bone mineral content, and bone area: United States, 2005–2008. Vital Health Stat 11. 2012 Mar;(251):1–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackey DC, Lui LY, Cawthon PM, et al. High-trauma fractures and low bone mineral density in older women and men. JAMA. 2007 Nov 28;298(20):2381–2388. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mueller DK, Kutscherenko A, Bartel H, Vlassenbroek A, Ourednicek P, Erckenbrecht J. Phantom-less QCT BMD system as screening tool for osteoporosis without additional radiation. Eur J Radiol. 2011 Sep;79(3):375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakagawa Y, Hattori M, Harada K, Shirase R, Bando M, Okano G. Age-related changes in intramyocellular lipid in humans by in vivo H-MR spectroscopy. Gerontology. 2007;53(4):218–223. doi: 10.1159/000100869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Crash Injury Research Engineering Network Coding Manual, Version 2.0. Department of Transportation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Osteoporosis Foundation. 54 Million Americans Affected by Osteoporosis and Low Bone Mass. 2014 http://nof.org/news/2948. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen ND, Eisman JA, Center JR, Nguyen TV. Risk factors for fracture in nonosteoporotic men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Mar;92(3):955–962. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perdue PW, Watts DD, Kaufmann CR, Trask AL. Differences in Mortality between Elderly and Younger Adult Trauma Patients: Geriatric Status Increases Risk of Delayed Death. J Trauma. 1998;45(4):805–810. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199810000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pickhardt PJ, Lee LJ, del Rio AM, et al. Simultaneous screening for osteoporosis at CT colonography: bone mineral density assessment using MDCT attenuation techniques compared with the DXA reference standard. J Bone Miner Res. 2011 Sep;26(9):2194–2203. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pickhardt PJ, Pooler BD, Lauder T, del Rio AM, Bruce RJ, Binkley N. Opportunistic screening for osteoporosis using abdominal computed tomography scans obtained for other indications. Ann Intern Med. 2013 Apr 16;158(8):588–595. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pintar FA, Yoganandan N, Maiman DJ, Scarboro M, Rudd RW. Thoracolumbar spine fractures in frontal impact crashes. Ann Adv Automot Med. 2012;56:277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pompe E, Willemink MJ, Dijkhuis GR, Verhaar HJ, Hoesein FA, de Jong PA. Intravenous contrast injection significantly affects bone mineral density measured on CT. Eur Radiol. 2015 Feb;25(2):283–289. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3408-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reid IR. Relationships among body mass, its components, and bone. Bone. 2002 Nov;31(5):547–555. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00864-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samelson EJ, Christiansen BA, Demissie S, et al. QCT measures of bone strength at the thoracic and lumbar spine: the Framingham Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2012 Mar;27(3):654–663. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shorr RM, Rodriguez A, Indeck MC, Crittenden MD, Hartunian S, Cowley RA. Blunt Chest Trauma in the Elderly. J Trauma. 1989;29(2):234–237. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198902000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stawicki SP, Grossman MD, Hoey BA, Miller DL, Reed JF., 3rd Rib fractures in the elderly: a marker of injury severity. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004 May;52(5):805–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stitzel JD, Kilgo PD, Weaver AA, Martin RS, Loftis KL, Meredith JW. Age thresholds for increased mortality of predominant crash induced thoracic injuries. Ann Adv Automot Med. 2010;54:41–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization. WHO Technical Report Series. Vol. 921. Geneva: 2003. Prevention and Management of Osteoporosis. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wuermser L-A, Achenbach SJ, Amin S, Khosla S, Melton LJ. What Accounts for Rib Fractures in Older Adults? Journal of Osteoporosis. 2011;2011:6. doi: 10.4061/2011/457591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu EW, Bouxsein ML, Roy AE, et al. Bone loss after bariatric surgery: discordant results between DXA and QCT bone density. J Bone Miner Res. 2014 Mar;29(3):542–550. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]