Abstract

Exposure to levamisole-adulterated cocaine can induce a distinct clinical syndrome characterized by retiform purpura and/or agranulocytosis accompanied by an unusual constellation of serologic abnormalities including antiphospholipid antibodies, lupus anticoagulants, and very high titers of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Two recent case reports suggest that levamisole-adulterated cocaine may also lead to renal disease in the form of pauci-immune glomerulonephritis. To explore this possibility, we reviewed cases of pauci-immune glomerulonephritis between 2010 and 2012 at an inner city safety net hospital where the prevalence of levamisole in the cocaine supply is known to be high. We identified 3 female patients and 1 male patient who had biopsy-proven pauci-immune glomerulonephritis, used cocaine, and had serologic abnormalities characteristic of levamisole-induced autoimmunity. Each also had some other form of clinical disease known to be associated with levamisole, either neutropenia or cutaneous manifestations. One patient had diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Three of the 4 patients were treated with short courses of prednisone and cyclophosphamide, 2 of whom experienced stable long-term improvement in their renal function despite ongoing cocaine use. The remaining 2 patients developed end-stage renal disease and became dialysis-dependent. This report supports emerging concern of more wide spread organ toxicity associated with the use of levamisole-adulterated cocaine.

INTRODUCTION

Now licensed exclusively as an antihelminthic for use in veterinary medicine, levamisole was once used as a putative immunomodulatory agent for the treatment of a variety of autoimmune conditions and malignancies. Toxicity eventually led to its withdrawal for human use in 1999. The most worrisome toxicities seen in adults were neutropenia and agranulocytosis, which occurred in 2.5%–13% of patients and resolved promptly with drug discontinuation.22,25,34 Small numbers of pediatric patients treated with prolonged courses of levamisole for refractory nephrotic syndrome developed a distinctive rash characterized by retiform purpura distributed on the face (nose, cheeks, and ear lobes) and proximal extremities. Biopsies of these purpuric lesions demonstrated thrombosis of superficial and deep dermal vessels with varying degrees of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Children with these rashes also had circulating antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) and antiphospholipid antibodies (APLAs). Upon discontinuation of levamisole, the purpura resolved within 2–3 weeks, and the autoantibodies disappeared over 2–14 months.20,28

In 2005, levamisole appeared as an adulterant in illicit cocaine entering the United States, presumably added by suppliers in an effort to increase cocaine volumes and enhance the perceived quality of the drug.5,16 The prevalence of this adulterant remained low through 2007 (detected in <10% of cocaine bricks seized by the United States Drug Enforcement Agency) but then rose sharply. By 2010, approximately 80% of all seized stocks of cocaine contained levamisole,4 indicating that exposure to levamisole had become almost ubiquitous among regular cocaine users. Indeed, 2 recent studies from inner-city hospitals identified levamisole in 63%-88% of urine samples that tested positive for cocaine.3,18 Levamisole toxicity has re-emerged as a medical problem with multiple reports linking the use of levamisole-adulterated cocaine to neutropenia, life-threatening agranulocytosis, and retiform purpura of the face and extremities.26,36,37,42 As reported in pediatric cases, adults with retiform purpura linked to levamisole-adulterated cocaine have an unusual combination of serologic abnormalities. First, they possess high titer ANCAs which stain in a perinuclear pattern (pANCA) due to autoantibodies against multiple components of neutrophil granules, including myeloperoxidase (MPO), proteinase 3 (PR3), human neutrophil elastase (HNE), lactoferrin, and cathepsin G. They also test positive for a lupus anticoagulant (LAC) and have APLAs, usually in the form of IgM antibodies to cardiolipin.12,37

A conspicuous feature of clinical disease associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine has been the paucity of organ involvement aside from the skin and granulocytes. Two recent case reports, however, raised the possibility of an association between the use of levamisole-adulterated cocaine and glomerulonephritis (GN).14,19 In the current study, we extend those observations and report 4 cases of biopsy-proven pauci-immune GN seen at a single institution over a 2-year period. All patients were active users of cocaine, had serologic abnormalities characteristic of levamisole-induced autoimmunity, and had at least 1 other clinical manifestation linked to use of levamisole (retiform purpura, digital infarcts, or neutropenia). These observations suggest that use of levamisole-adulterated cocaine can trigger a pauci-immune GN similar to that seen with the primary ANCA vasculitides, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA).

METHODS

We reviewed the medical records of all cases of pauci-immune GN seen at San Francisco General Hospital from 2010 through 2012. The study was approved by the San Francisco General Hospital institutional review board. For inclusion in this series, patients had to have the following: 1) pauci-immune GN on renal biopsy, 2) cocaine exposure confirmed either by patient history or by urine toxicology studies, and 3) serologic abnormalities characteristic of levamisole-induced autoimmunity. We defined the latter as a positive test for ANCA in a perinuclear pattern (pANCA) by indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) together with at least 1 of the following: simultaneous presence of antibodies to MPO and PR3 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), a LAC detected by dilute Russell viper venom time, or presence of IgM antibodies to cardiolipin. Because nearly 90% of cocaine in San Francisco is adulterated with levamisole, we accepted cocaine use as a proxy for levamisole exposure.18 Renal biopsies were reviewed by a renal pathologist (KJ) to confirm the presence of pauci-immune GN.

RESULTS

We identified 3 female patients and 1 male patient who had biopsy-proven pauci-immune GN, used cocaine, and had serologic abnormalities characteristic of levamisole-induced autoimmunity. All patients reported smoking cocaine, and all tested positive for cocaine on urine toxicology screens, except for 1 who was anuric. Each had some form of clinical disease known to be associated with levamisole, either neutropenia or cutaneous disease manifesting as retiform purpura or digital infarcts (Table 1). All patients had elevated levels of serum creatinine, and the 3 patients who were not anuric on presentation had proteinuria and an active urinary sediment, defined as the presence of dysmorphic red blood cells or the presence of red blood cell casts (Table 2). All 4 patients had pANCAs in titers ≥1:320 as measured by IIF. Two patients had antibodies to both MPO and PR3, whereas the others had antibodies to MPO alone. Three patients either tested positive for a LAC or had a circulating IgM antibody to cardiolipin (Table 3).

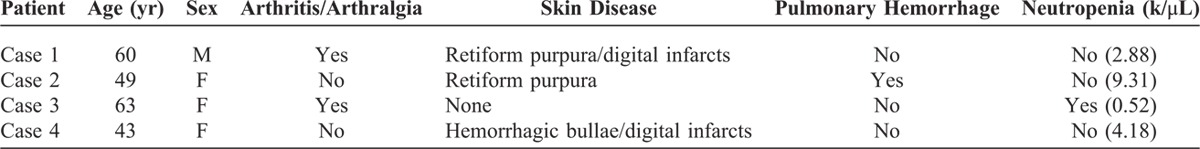

TABLE 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients Presenting With Pauci-Immune Glomerulonephritis Associated With Levamisole-Adulterated Cocaine Exposure

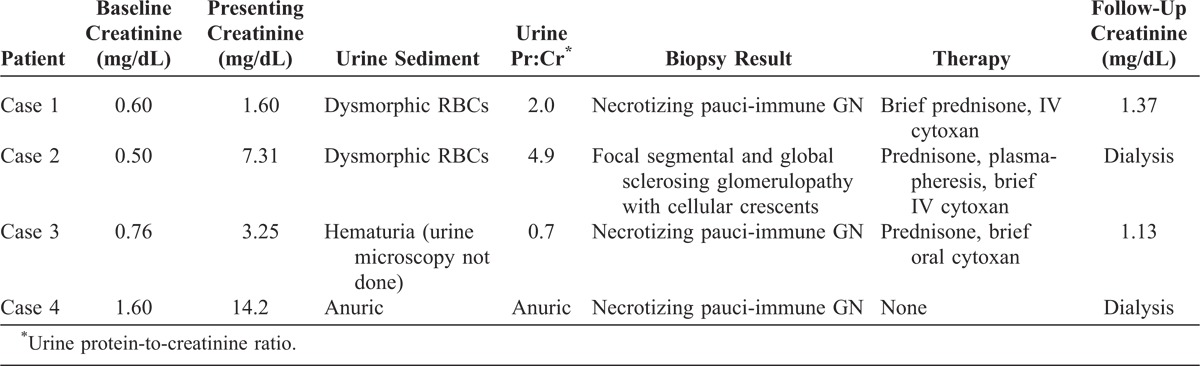

TABLE 2.

Renal Manifestations and Outcomes of Patients Presenting With Pauci-Immune Glomerulonephritis Associated With Levamisole-Adulterated Cocaine Exposure

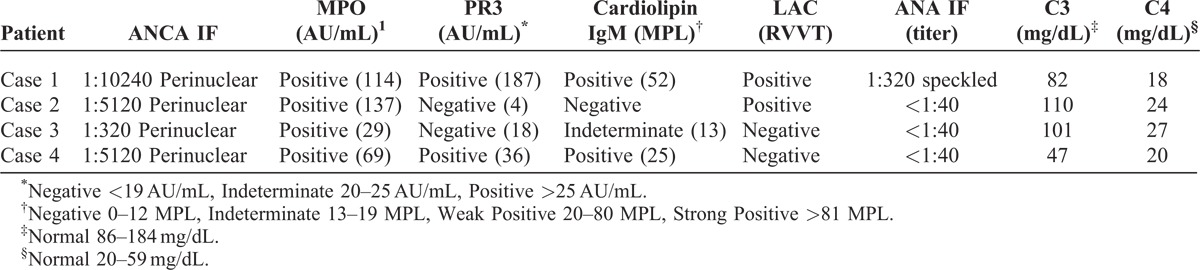

TABLE 3.

Immunologic and Coagulation Profiles of Patients Presenting With Pauci-Immune Glomerulonephritis Associated With Levamisole-Adulterated Cocaine Exposure

Kidney biopsies from each patient in this series demonstrated changes consistent with pauci-immune GN. Three biopsies (Cases 1, 3, and 4) exhibited evidence of recent/ongoing activity as supported by numerous cellular crescents and necrotizing lesions, while the other biopsy (Case 2) showed more remote signs of glomerular injury with presence of fibrous and fibrocellular crescents. The latter biopsy also revealed a higher percentage of global glomerulosclerosis and a greater degree of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, findings associated with chronic stages of GN. Otherwise, the nonsclerotic glomeruli in all biopsies were essentially unremarkable with no significant endocapillary proliferation, mesangial widening, or mesangial hypercellularity. The biopsies showed no evidence of thrombotic microangiopathy or malignant hypertension, which can be seen in association with cocaine use.13 The larger vessels within the renal parenchyma showed no evidence of frank vasculitis. Immunofluorescence for IgG, IgM, IgA, C3 and C1q was negative in all cases, supporting the diagnosis of pauci-immune GN. Ultrastructural analysis by electron microscopy confirmed the absence of electron dense immune-type deposits.

Three of the 4 patients were treated with short courses of prednisone and cyclophosphamide. Two of the treated patients had stable long-term improvement in their renal function despite ongoing cocaine use. The remaining 2 patients developed end-stage renal disease and became dialysis-dependent.

Case 1

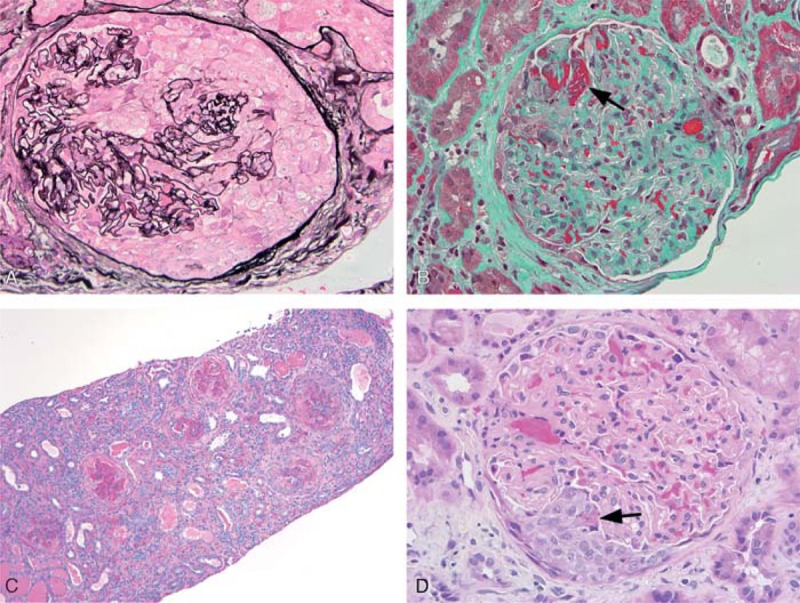

A 60-year-old man with a history of chronic cocaine use was admitted with a 2-week illness characterized by polyarthralgia and the development of retiform purpura on the upper extremities and overlying the zygomatic arches of the face. Serum creatinine was 1.60 mg/dL, increased from a baseline of 0.60 mg/dL measured 4 months previously. Urinalysis revealed proteinuria and hematuria with dysmorphic red blood cells. A urine toxicology screen was positive for cocaine. Serologic studies were notable for a high titer pANCA and the presence of antibodies to MPO and PR3. He tested positive for a LAC and had IgM and IgG antibodies to cardiolipin. Biopsy of a purpuric lesion revealed congestion and thrombosis of the superficial and mid-dermal vessels without evidence of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. A kidney biopsy showed pauci-immune GN with focal necrotizing lesions and crescent formation (Figure 1A and 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Kidney biopsy histologic findings. A) Glomerulus from Case 1 with a large cellular crescent (methenamine silver-periodic acid-Schiff; 400x). B) Glomerulus from Case 1 showing fibrin (arrow) of a necrotizing lesion (trichrome; 400x). C) Medium power view of biopsy from Case 4 demonstrating a range of cellular to fibrocellular crescents. Features of mild interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and interstitial inflammation are also noted (periodic acid-Schiff; 100x). D) Glomerulus from Case 4 showing a small cellular crescent with associated fibrin of a necrotizing lesion (arrow) (hematoxylin & eosin; 400x).

Three daily intravenous doses of 500 mg methylprednisolone were administered, followed by oral prednisone 60 mg daily. During the 10-day hospitalization, the skin lesions improved and the serum creatinine, which had peaked at 2.16 mg/dL, improved to 1.64 mg/dL. After discharge, the patient continued using cocaine and discontinued all prescribed medications. Two weeks later, he was readmitted with recurrent retiform purpura and a creatinine of 2.51 mg/dL. Urine microscopy revealed a persistently active urine sediment. Oral prednisone was restarted, and he received a single 750 mg dose of intravenous cyclophosphamide. Over the next 2 weeks his skin lesions resolved, and creatinine improved to 1.43 mg/dL. He was discharged on prednisone alone with plans for monthly infusions of cyclophosphamide but failed to keep any appointments. On a visit to a different clinic 19 months after his renal biopsy, he had a serum creatinine of 1.37 mg/dL, persistent hematuria and proteinuria, and a positive urine toxicology study for cocaine.

Case 2

A 49-year-old woman with hepatitis C, chronic leg ulcers, and a history of cocaine abuse was admitted with painful purpuric lesions on the left leg and an associated cellulitis. Initial laboratories on admission showed acute kidney injury with a serum creatinine of 1.88 mg/dL, elevated from her baseline of 0.50 mg/dL measured 1 year previously. Urinalysis revealed hematuria and proteinuria, and examination of the urine sediment demonstrated red blood cell casts. She received parenteral antibiotics with gradual improvement in her cellulitis. Creatinine remained stable throughout her hospitalization, ranging from 1.72 to 1.88 mg/dL. Prior to discharge, she underwent serologic testing and a skin biopsy of the purpuric lesions with plans to follow-up as an outpatient. Skin biopsy revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis and rare fibrin thrombi of the superficial and deep dermal vessels. Serologic studies were notable for the presence of antibodies to MPO and IgM antibodies to cardiolipin. She had no antibodies to PR3. She did not attend any of the scheduled outpatient follow-up appointments.

Five months later, she presented with hemoptysis and acute onset dyspnea. On presentation, she was hypoxemic with bilateral pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiograph. She was severely anemic with a hemoglobin of 6.7 g/dL and had acute kidney injury with a serum creatinine of 7.31 mg/dL. Urinalysis revealed hematuria and proteinuria, and examination of the urine sediment demonstrated dysmorphic red blood cells. A urine toxicology screen was positive for cocaine. She was admitted to the intensive care unit with hypoxemic respiratory failure and started urgently on hemodialysis. Bronchoscopy findings were consistent with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage.

She was transfused with several units of packed red blood cells and received 3 daily intravenous doses of 1000 mg methylprednisolone, 3 sessions of plasma exchange, and a single intravenous dose of 500 mg cyclophosphamide, followed by oral prednisone 60 mg daily. Serologic studies were notable for a high-titer pANCA, the presence of antibodies to MPO, and a positive test for a LAC. Renal biopsy demonstrated presence of fibrous and fibrocellular crescents, consistent with pauci-immune GN with evolving chronic changes due to prior activity. Following her initial course of therapy, the patient had no further alveolar hemorrhage but remained dialysis-dependent.

Case 3

A 63-year-old woman with a long history of cocaine abuse presented to her primary care provider with diffuse pruritis and arthralgia. Serum creatinine was 3.25 mg/dL, up from her baseline of 0.76 mg/dL measured 1 year previously, which prompted a hospitalization for expedited workup. Upon admission, she was neutropenic with an absolute neutrophil count of 520 cells/mL, and urinalysis revealed hematuria and proteinuria. A serologic workup was notable for a positive pANCA at a titer of 1:320, antibodies to MPO, and a weakly positive IgM antibody to cardiolipin. A kidney biopsy revealed pauci-immune necrotizing and crescentic GN.

Three daily intravenous doses of 1000 mg methylprednisolone were administered. She was then transitioned to oral prednisone 60 mg daily and oral cyclophosphamide 50 mg daily. One month after starting cyclophosphamide, she developed herpes ophthalmicus for which she was started on intravenous acyclovir, and her cyclophosphamide was discontinued. She was poorly compliant with her outpatient medications and eventually discontinued her prednisone. Serum creatinine remained stable at approximately 1.20 mg/dL over the ensuing 24 months despite intermittent use of cocaine.

Case 4

A 43-year-old woman with hepatitis C and a history of cocaine abuse was admitted with altered mental status. Physical examination revealed altered mental status, a pericardial friction rub, hemorrhagic bullae overlying her fingers, and distal digital infracts. She was anuric and had a serum creatinine of 14.30 mg/dL. She received urgent hemodialysis for symptomatic uremia with improvement in her mental status. Subsequent serologic workup revealed a pANCA with a titer of 1:5120, antibodies to both MPO and PR3, and IgM antibodies to cardiolipin. A kidney biopsy demonstrated pauci-immune necrotizing and crescentic GN with presence of fibrocellular and fibrous crescents (Figure 1C and 1D). She remained dialysis-dependent but continued to use cocaine and died from an intracerebral hemorrhage several months following discharge.

DISCUSSION

Levamisole-Adulterated Cocaine and Internal Organ Manifestations

We report 4 cases of chronic cocaine users presenting with biopsy-proven pauci-immune crescentic GN, one of whom had concurrent diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. All patients had clinical manifestations (skin disease or neutropenia) and serologic abnormalities characteristic of the syndrome associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. Two other cases of biopsy-proven pauci-immune GN linked to levamisole-adulterated cocaine have recently been published. Gulati et al reported on a 49-year-old Hispanic man who presented with retiform purpura, acute kidney injury, and an active urinary sediment.14 The patient’s laboratory studies were notable for MPO antibodies at high titers as well as a LAC. McGrath et al reported a case involving a 53-year-old woman who similarly presented with retiform purpura, acute kidney injury, and an active urinary sediment.19 She tested positive for both MPO and PR3 at high titers. Both of these patients underwent renal biopsies, which showed pauci-immune necrotizing crescentic GN. Taken together with the current series, these reports support the emerging concern that prolonged use of levamisole-adulterated cocaine can lead to a drug-induced autoimmune disease complicated by a clinically significant pauci-immune GN.

In contrast to neutropenia and retiform purpura, pauci-immune GN was not observed as a complication of levamisole when it was used therapeutically as an immunomodulatory agent. There was a reported case of renal insufficiency and GN linked to the use of levamisole for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, but the renal biopsy revealed an immune-complex-mediated proliferative GN with subepithelial deposits. After withdrawal of levamisole, the patient’s renal function improved.31 There were no purpuric rashes or cytopenias described in this case, which antedated the development of tests for ANCAs and APLAs. The association of levamisole with a pauci-immune GN, therefore, appears to represent a new clinical phenomenon.

Differentiating Levamisole-Induced Disease From Other Forms of ANCA-Associated Systemic Vasculitis

The primary ANCA associated vasculitides (AAVs) include GPA, MPA, and eosinophilic microscopic polyangiitis. These diseases affect multiple organ systems including the upper airways, lung parenchyma, peripheral nerves, skin, and kidneys. The drug-induced AAVs caused by agents such as hydralazine and propylthiouracil (PTU) manifest with clinical features that overlap to a significant degree with the primary forms of the disease, particularly MPA.7,10 A similar spectrum of organ involvement appears to occur in patients with disease associated with the use of levamisole-adulterated cocaine.19 Given variations in the treatment and prognosis of these different vasculitides, it is important to differentiate levamisole-induced disease from the primary and other secondary forms of AAV.

It has been previously noted that ANCA serologies themselves allow for differentiation of the primary and drug-induced AAVs.10,39 Patients with disease associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine tend to develop high to extremely high titer ANCAs when measured by IIF, most often in a perinuclear staining pattern. The ANCA antibodies in these and other cases of drug-induced AAV are directed at multiple antigenic targets within neutrophilic granules, primarily MPO, HNE, cathepsin G, and lactoferrin.7,10,12,15,32,33 HNE and cathepsin G share epitopes with PR3, and antibodies to these can result in a falsely positive anti-PR3 immunoassay due to cross reactivity. It is therefore possible to see a high titer pANCA and a discordantly positive anti-PR3 antibody in those with drug-induced AAV.30,38,39 In contrast, the primary AAVs demonstrate modest ANCA titers on IIF due to antibodies against either PR3 or MPO rather than multiple neutrophilic antigens.38,39 Unlike the primary AAVs, many agents linked to drug-induced AAVs, including levamisole-adulterated cocaine, have also been shown to lead to positive antinuclear antibodies (ANAs).7,32 Though clinical and serologic similarities exist among the drug-induced AAVs, the discriminating features of the illness associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine remain its unique cutaneous manifestations (retiform purpura), the frequent occurrence of neutropenia, and the presence of APLAs and a LAC.

Differentiating the Complications of Levamisole-Adulterated Cocaine From Those of Pure Cocaine Use

Cocaine use, independent of the presence of adulterants, is associated with varying rheumatic manifestations. These include cocaine-induced midline destructive lesion (CIMDL), organ specific and systemic vasculitides, and vascular disease related to stimulant-induced vasospasm.11 Despite the widespread use of cocaine, CIMDL and cocaine-induced vasculitis remain relatively uncommon. When these clinical manifestations do occur, they are associated with 1 of 3 serologic profiles which include: no circulating autoantibodies in those with organ limited disease,6,17,21 a positive cANCA and PR3 antibody in those with multi-systemic disease mirroring GPA,24 and a positive pANCA and PR3 antibody in those with CIMDL.35 The unexpected serologic discrepancy seen with CIMDL is due to the presence of antibodies to HNE. Antibodies directed at HNE have not been detected in patients with GPA and are rarely reported in MPA and eosinophilic microscopic polyangiitis.38,39

Because cocaine, like levamisole, can induce loss of tolerance to multiple targets within the neutrophilic granule, one must rely on other features to differentiate pathology associated with unadulterated cocaine from that of cocaine laced with levamisole. The unique cutaneous findings associated with levamisole are helpful if present, but otherwise one must use discriminating laboratory features. Patients with clinical disease associated with unadulterated cocaine have not been shown to develop APLAs or a LAC and do not develop neutropenia.8,12

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanism by which medications such as hydralazine, PTU, and levamisole induce ANCA-associated syndromes remains unclear, but studies have implicated neutrophil extracellular traps (NETS) in the pathogenesis of these conditions.23,29 NETs are comprised of a scaffold of chromatin DNA intermingled with histones and constituents of cytoplasmic PMN granules, including MPO, PR3, and HNE. These elements are released from neutrophils during a unique form of cell death in response to various stimuli, including intact pathogens, pathogen components, and high levels of reactive oxygen species. Antibodies and antibody-antigen complexes have also been shown to induce NET release, though to a lesser degree.2 NETs may provide a source of intact antigen capable of inducing an adaptive immune response, leading to the production of ANCAs.29 PTU in particular has been shown to cause production of disorganized NETs that are resistant to normal homeostatic mechanisms of degradation. Immunization of rats with these abnormal NETs leads to pulmonary capillaritis and pauci-immune GN.23 It is possible that levamisole, like PTU, acts via this mechanism to induce loss of tolerance to multiple antigens from within neutrophil granules, resulting in clinical disease.

Genetic and environmental factors likely play a role in the pathogenesis of disease related to levamisole exposure. Patients carrying an HLAB27 allele are known to be at higher risk of developing agranulocytosis when treated with levamisole.40 Demethylation of particular DNA sequences leading to altered expression of specific genes appears to play an important role in the pathogenesis of lupus-like syndromes induced by procainamide and hydralazine.27,41 Whether disruption of this type of epigenetic control also contributes to levamisole-induced autoimmunity is not known.

Many patients on agents such as PTU and hydralazine develop circulating ANCAs yet never develop vasculitis.15,33 This phenomenon is likely true in those exposed to levamisole given the widespread use of cocaine, the high prevalence of levamisole in the drug supply, and the relatively low incidence of retiform purpura, neutropenia, and GN in chronic cocaine users. The factors that distinguish those who develop clinical disease from those who do not remain unclear.

One important factor seems to be the chronicity of drug exposure. Patients with drug-induced AAVs and internal organ involvement have typically been exposed to offending agents for prolonged periods of time, often on the order of years. With regard to levamisole-adulterated cocaine, it is only in the past several years that cases of pauci-immune GN linked to levamisole have emerged. These more recent cases may reflect the effect of chronic exposure to levamisole, which has now been present in the illicit cocaine supply since 2005. With this timeline in mind, agranulocytosis, retiform purpura, and circulating autoantibodies may represent an earlier phase of levamisole-induced disease. With further exposure, patients may be at increased risk of developing renal involvement. Why patients previously treated with prolonged courses of therapeutic levamisole alone did not develop pauci-immune GN is unknown. It may be that cocaine acts synergistically with levamisole to result in a more advanced clinical phenotype. Alternatively, renal involvement may represent a dose dependent effect of levamisole or a variable response related to the route of drug administration. All patients in the current series reported smoking crack cocaine whereas all patients on therapeutic doses of levamisole in the past took oral formulations.

Treatment

The treatment of drug-induced AAVs due to hydralazine and PTU provides a helpful framework for strategies in those patients with end-organ damage associated with exposure to levamisole-adulterated cocaine. The mainstay of therapy for drug-induced AAVs is withdrawal of the offending agent. For patients with end-organ involvement (GN or pulmonary hemorrhage), short courses of immunosuppressives appear to be efficacious and result in durable remission rates provided that patients are identified early.9,10 Patients with pulmonary hemorrhage may be treated with plasmapheresis in addition to immunosuppression.

In the current series, 3 of the 4 patients were treated with short courses of prednisone and cyclophosphamide. Although they were counseled to abstain from cocaine, all continued to use the drug. It is noteworthy that despite these relapses and presumed repeated exposures to levamisole, short courses of immunosuppressive therapy were associated with improvement and stabilization of renal function in 2 patients over the course of 19–24 months. The other patients in the series remained dialysis-dependent, but they initially presented with more advanced renal disease. In contrast, the case reported by Gulati et al was treated in the same manner as a primary AAV with a short course of prednisone, 4 infusions of rituximab, and maintenance with azathioprine. This treatment course was associated with a partial remission and interval improvement in the patient’s creatinine to a new baseline. The case presented by McGrath et al received an unknown course of immunosuppressives, which was also associated with a partial remission. These cases suggest that durable responses can be achieved with short courses of aggressive immunosuppressive therapy even in the face of ongoing exposure to levamisole. It is not known however whether successfully treated patients will ultimately relapse if re-exposed to levamisole-adulterated cocaine on a persistent basis.

Limitations

Since 88% of urine samples testing positive for cocaine at San Francisco General Hospital also contain levamisole,18 we assumed that all patients with a history of cocaine use were exposed to levamisole. No confirmatory studies were performed to verify levamisole in patient samples from the current series. We limited the scope of this series to include only patients with biopsy-proven pauci-immune GN. It is possible that there are other forms of GN, such as immune complex-mediated disease, that are associated with levamisole use. Finally, no firm conclusions can be drawn regarding the efficacy of any of the therapeutic interventions we describe. We did not conduct a therapeutic trial, and the natural history of pauci-immune GN associated with levamisole remains uncertain.

Conclusion

In conclusion, levamisole-adulterated cocaine not only results in retiform purpura and neutropenia, but can also lead to a pauci-immune GN, and possibly pulmonary hemorrhage, in the setting of chronic drug exposure. There are unique exam and laboratory findings that help differentiate the syndrome associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine from the primary and drug-induced AAVs. Important discriminating laboratory features include the presence of APLAs and LACs in combination with high titer ANCAs measured by IIF and positive antibodies to multiple constituents of the neutrophilic granule. The mainstay of treatment is abstinence from cocaine and, by extension, levamisole. Though additional observations are needed, it appears that those patients with severe end-organ involvement can be treated with short courses of immunosuppressives without maintenance regimens.

Cocaine is a common drug of abuse. In 2008, an estimated 1.9 million individuals in the United States reported cocaine use within the past month, of which approximately 19% were current crack users.1 In light of this widespread use and the high prevalence of levamisole in the illicit cocaine supply in the United States, clinicians may expect cases of drug-induced AAV with internal organ involvement to occur with greater frequency in the future. Given the divergent treatment strategies for primary and drug-induced AAVs, it is important for medical providers to maintain a high level of suspicion for disease associated with levamisole in long-term cocaine users.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AAV = ANCA-associated vasculitis, ANCA = antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, APLA = antiphospholipid antibody, ANA = antinuclear antibody, cANCA = cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, CIMDL = cocaine-induced midline destructive lesion, ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, GN = glomerulonephritis, GPA = granulomatosis with polyangiitis, HNE = human neutrophil elastase, IIF = indirect immunofluorescence, LAC = lupus anticoagulant, MPA = microscopic polyangiitis, MPO = myeloperoxidase, NET = neutrophil extracellular trap, pANCA = perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, PR3 = proteinase 3, PTU = propylthiouracil.

Financial support and conflicts of interest: Funding was provided in part by the Rosalind Russell Arthritis Foundation and US Department of Veterans Affairs (AQC). DST is supported by K23DK094850 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Anonymous. Cocaine: abuse and addiction. National Institues of Health. 2010. Available from: http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/cocaine-abuse-addiction/what-scope-cocaine-use-in-united-states. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps: is immunity the second function of chromatin? J Cell Biol. 2012;198:773–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casale JF, Colley VL, LeGatt DF. Determination of phenyltetrahydroimidazothiazole enantiomers (levamisole/dexamisole) in illicit cocaine seizures and in the urine of cocaine abusers via chiral capillary gas chromatographyflame-ionization detection: clinical and forensic perspectives. J Anal Toxicol. 2012;36:130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casale JF, Cobreil EM, Hays PA. Identification of levamisole impurities found in illicit cocaine exhibits. Microgram Journal. 2008;6:82–89. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen SC, Jang MY, Wang CS, et al. Cocaine-related vasculitis causing scrotal gangrene. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:375–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi HK, Merkel PA, Walker AM, et al. Drug-associated antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive vasculitis: prevalence among patients with high titers of antimyeloperoxidase antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:405–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman DR, Wolfsthal SD. Cocaine-induced pseudovasculitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:671–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Y, Chen M, Ye H, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with propylthiouracil-induced anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic auto-antibody-associated vasculitis. Rheumatology. 2008;47:1515–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao Y, Zhao MH. Review article: drug-induced anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Nephrology (Carlton). 2009;14:33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graf J. Rheumatic manifestations of cocaine use. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graf J, Lynch K, Yeh CL, et al. Purpura, cutaneous necrosis, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3998–4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu X, Herrera GA. Thrombotic microangiopathy in cocaine abuse-associated malignant hypertension: report of 2 cases with review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1817–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gulati S, Donato AA. Lupus anticoagulant and ANCA associated thrombotic vasculopathy due to cocaine contaminated with levamisole: a case report and review of the literature. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2012;34:7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunton JE, Stiel J, Clifton-Bligh P, et al. Prevalence of positive anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) in patients receiving anti-thyroid medication. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;142:587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall AB, Coy SL, Nazarov EG, et al. Rapid separation and characterization of cocaine and cocaine cutting agents by differential mobility spectrometry-mass spectrometry. J Forensic Sci. 2012;57:750–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofbauer GF, Hafner J, Trueb RM. Urticarial vasculitis following cocaine use. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:600–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch KL, Dominy SS, Graf J, et al. Detection of levamisole exposure in cocaine users by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Anal Toxicol. 2011;35:176–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGrath MM, Isakova T, Rennke HG, et al. Contaminated cocaine and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2799–2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menni S, Pistritto G, Gianotti R, et al. Ear lobe bilateral necrosis by levamisole-induced occlusive vasculitis in a pediatric patient. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:477–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merkel PA, Koroshetz WJ, Irizarry MC, et al. Cocaine-associated cerebral vasculitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1995;25:172–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mielants H, Veys EM. A study of the hematological side effects of levamisole in rheumatoid arthritis with recommendations. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1978;4:77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakazawa D, Tomaru U, Suzuki A, et al. Abnormal conformation and impaired degradation of propylthiouracil-induced neutrophil extracellular traps: implications of disordered neutrophil extracellular traps in a rat model of myeloperoxidase antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:3779–3787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neynaber S, Mistry-Burchardi N, Rust C, et al. PR3-ANCA-positive necrotizing multi-organ vasculitis following cocaine abuse. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:594–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parkinson DR, Cano PO, Jerry LM, et al. Complications of cancer immunotherapy with levamisole. Lancet. 1977;1:1129–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poon SH, Baliog CR, Jr., Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leukopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richardson B. DNA methylation and autoimmune disease. Clin Immunol. 2003;109:72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rongioletti F, Ghio L, Ginevri F, et al. Purpura of the ears: a distinctive vasculopathy with circulating autoantibodies complicating long-term treatment with levamisole in children. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:948–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sangaletti S, Tripodo C, Chiodoni C, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps mediate transfer of cytoplasmic neutrophil antigens to myeloid dendritic cells toward ANCA induction and associated autoimmunity. Blood. 2012;120:3007–3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savige JA, Paspaliaris B, Silvestrini R, et al. A review of immunofluorescent patterns associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) and their differentiation from other antibodies. J Clin Pathol. 1998;51:568–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shearn MA, Tu WH. Proliferative glomerulonephritis associated with levamisole therapy of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1981;8:522–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Short AK, Lockwood CM. Antigen specificity in hydralazine associated ANCA positive systemic vasculitis. Q J Med. 1995;88:775–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slot MC, Links TP, Stegeman CA, Tervaert JW. Occurrence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and associated vasculitis in patients with hyperthyroidism treated with antithyroid drugs: a long-term followup study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Symoens J, Veys E, Mielants M, et al. Adverse reactions to levamisole. Cancer Treat Rep. 1978;62:1721–1730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trimarchi M, Nicolai P, Lombardi D, et al. Sinonasal osteocartilaginous necrosis in cocaine abusers: experience in 25 patients. Am J Rhinol. 2003;17:33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waller JM, Feramisco JD, Alberta-Wszolek L, et al. Cocaine-associated retiform purpura and neutropenia: is levamisole the culprit. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:530–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walsh NM, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiesner O, Russell KA, Lee AS, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies reacting with human neutrophil elastase as a diagnostic marker for cocaine-induced midline destructive lesions but not autoimmune vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2954–2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiik A, Stummann L, Kjeldsen L, et al. The diversity of perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCA) antigens. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;101:15–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolford A, McDonald TS, Eng H, et al. Immune-mediated agranulocytosis caused by the cocaine adulterant levamisole: a case for reactive metabolite(s) involvement. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40:1067–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou Y, Lu Q. DNA methylation in T cells from idiopathic lupus and drug-induced lupus patients. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;7:376–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu NY, Legatt DF, Turner AR. Agranulocytosis after consumption of cocaine adulterated with levamisole. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:287–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]