Abstract

Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy (PTTM) is a rare clinical entity where tumor cell embolisms in pulmonary circulation induce thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), respiratory failure, and subacute cor pulmonale.

We describe 3 cases of PTTM that presented as the initial manifestation of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma with TMA and pulmonary infiltrates.

All 3 cases had similar clinical and laboratory features, which included moderate thrombocytopenia without renal failure, hemolysis with extremely high serum lactate dehydrogenase levels, leukoerythroblastosis in peripheral blood smear, altered coagulation tests, lymphadenopathies, and interstitial pulmonary infiltrates. All patients died within 2 weeks of diagnosis. Two cases were initially misdiagnosed as idiopathic thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and treated with plasma exchange with no response. One patient had bone marrow infiltration by malignant cells. Autopsies revealed PTTM associated with gastric disseminated adenocarcinoma (signet-ring cell type in 2 patients and poorly differentiated type in 1).

PTTM should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with fulminant microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, such as atypical thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, mainly those with pulmonary infiltrates, disseminated intravascular coagulation, or Trousseau syndrome.

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy (PTTM) is a rare clinical entity where tumor cell embolisms in pulmonary circulation induce thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), respiratory failure, and subacute cor pulmonale. TMA is a disorder characterized by thrombocytopenia, Coombs negative microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA), and variable degrees of organ dysfunction.23

Diagnosis of PTTM is challenging. It is often misdiagnosed as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP),23 and the patient is started on plasma exchange therapy. However, such treatment is ineffective and the disease usually progresses quickly to a fatal outcome. Therefore, prompt etiologic diagnosis is very important because the only chance for the patient is to achieve a response to tumor-specific chemotherapy. We present hereby 3 patients with PTTM presenting with TMA and lung involvement admitted to the same hospital. We note that these patients presented features of TTP but with atypical characteristics that can help to shape the differential diagnosis. We also address other potential differential diagnoses.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We describe 3 cases of PTTM that presented as the initial manifestation of metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma with TMA and pulmonary infiltrates. All 3 patients had similar clinical and laboratory features and were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) of the same hospital due to the severity and clinical complications during the hospitalization. All patients died within 2 weeks of diagnosis. As this is a retrospective and descriptive study with no intervention, and figures do not show identifiable patients, institutional review board approval and informed consents were waived.

Literature Search

We also present a literature review based on relevant articles for PTTM, TMA, MAHA, TTP, and Trousseau syndrome published in PubMed (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD) in the English language up to February 2014.

CASE REPORTS

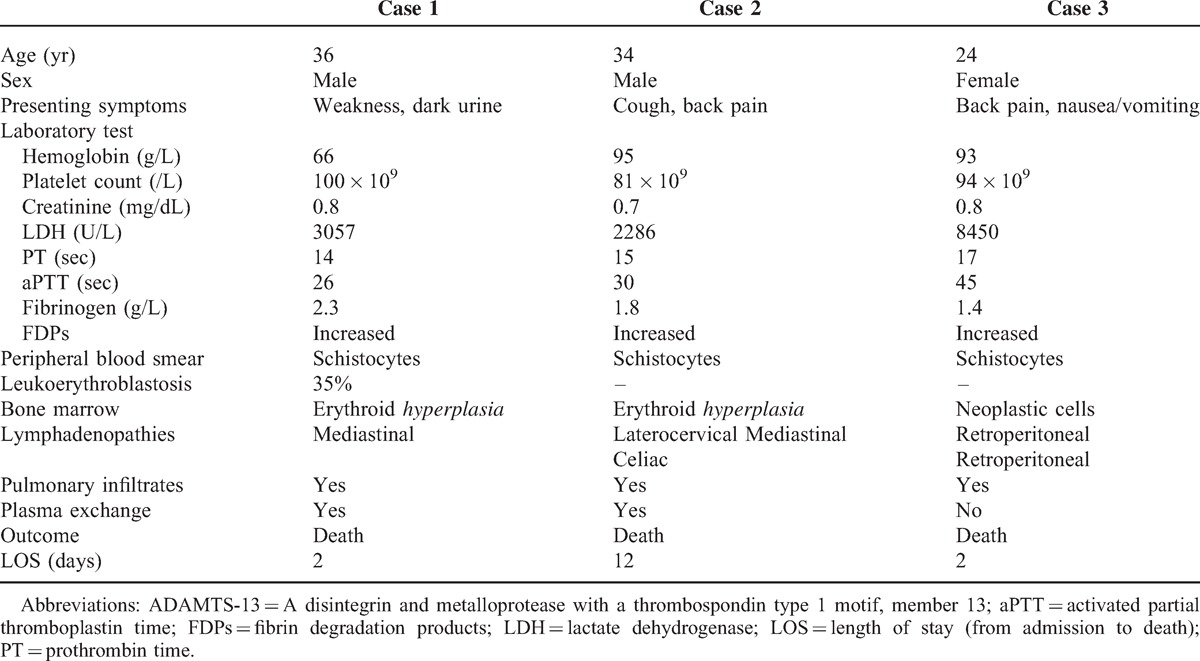

The main clinical and laboratory features of the 3 cases are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Main Clinical and Laboratory Features of the 3 Cases

Case 1

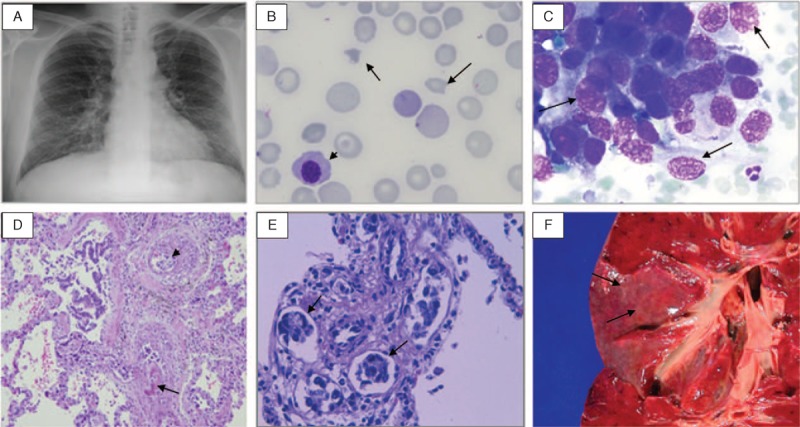

A 36-year-old Brazilian man without relevant past medical history came to our hospital complaining of 1-week weakness and dark urine. Vital signs were normal and he was apyretic. Physical examination revealed pale skin, jaundice and petechiae on the upper limbs. Laboratory tests showed signs of MAHA (hemoglobin 66 g/L, total bilirubin 4.1 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 0.8 mg/dL, reticulocyte count 190 × 109/L, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 3057 U/L, undetectable haptoglobin, and schistocytes in the peripheral blood smear). White blood cell count and creatinine were normal. Platelet count was 100 × 109/L, prothrombin time (PT) was 14 sec, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) was 26 sec, fibrinogen was 2.3 g/L and fibrinogen degradation products (FDPs) were increased. The direct antiglobulin (Coombs) test (DAT) was negative. Bone marrow aspiration detected erythroblastosis without abnormalities in other lineages. Chest X-ray demonstrated bilateral interstitial pulmonary infiltrates (Figure 1A) and the patient was hypoxemic. He was admitted to the ICU with an initial diagnosis of TTP and plasma exchange therapy was started without improvement. Invasive mechanical ventilation was needed due to progressive respiratory failure. Chest and abdomen computed tomography (CT) demonstrated mediastinal and celiac lymphadenopathies. A result of ADAMTS-13 (a desintegrin and metalloprotease with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13) activity of 35% in the initial plasma sample was received. Two days after admission the patient died due to refractory hypoxemia. Autopsy was performed.

FIGURE 1.

A. Chest X-ray with interstitial bilateral infiltrates (Case 1). B. Schistocytes (arrows) and an erythroblast (arrowhead) in the peripheral blood smear (Case 3). C. Neoplastic cells in bone marrow (arrows) (Case 3). D. Blood vessels with eccentric intimal fibrosis (arrow), intravascular fibrin thrombi, and recanalization and intraluminal emboli of neoplastic cells (arrowhead) (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification × 100) (Case 3). E. Carcinoma emboli in perivascular lymphatic vessels (arrows) (hematoxylin and eosin, × 400) (Case 1). F. Autopsy specimen of the lung showing prominent lymphatic vessels (carcinomatous lymphangitis) in pleural surface as fine white lines (Case 3).

Case 2

A 34-year-old Peruvian man without relevant past medical history presented to the emergency room referring 1 month of asthenia, cough, headache and lumbar pain. Physical examination showed pale skin, jaundice, laterocervical lymphadenopathies and bilateral basal rales. In the laboratories he presented elevated liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase 388 U/l, alanine aminotransferase 75 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 450 U/L), signs of MAHA (hemoglobin 81 g/L, total bilirubin 4.2 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 1.3 mg/dL, reticulocyte count 265 × 109/L, LDH 2286 U/L, haptoglobin 0.071 g/L, and peripheral blood smear with schistocytes) and platelet count of 95 × 109/L. Coagulation test showed PT 15 sec, aPTT 30 sec, fibrinogen 1.8 g/L and increased FDPs. Creatinine was normal. DAT was negative. Chest X-ray and CT scan demonstrated bilateral interstitial infiltrates, infracentrimetric mediastinal and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathies, hypodense hepatic lesions and ascites. Bone marrow aspirate excluded infiltration by malignant cells. Corticosteroids and plasma exchange were administered with no improvement. A lymph node and a percutaneous liver biopsy with a Tru-Cut needle were performed showing metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma of signet-ring cell type in the lymph node and sinusoidal infiltration by carcinoma cells in the liver. The outcome was complicated with hemoperitoneum after liver biopsy and the patient was transferred to the ICU. Administration of chemotherapy was ruled out due to poor patient's clinical condition. Twelve days after admission the patient died of multiple organ dysfunction due to several complications, such as pulmonary distress and Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Autopsy was not done.

Case 3

A 24-year-old Bolivian woman without relevant past medical history was referred to our hospital for further study of 3-weeks back pain, nausea and vomiting. At admission she appeared pale. Laboratory tests showed increased alkaline phosphatase (855 U/L), signs of MAHA (hemoglobin 93 g/dL, total bilirubin 8.1 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 2.3 mg/dL, reticulocyte count 267 × 109/L, LDH 8450 U/L, haptoglobin 0.04 g/L, and schistocytes in peripheral blood smear), 94 × 109/L platelets and signs of disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) (PT 17 sec, aPTT 45 sec, fibrinogen 1.4 g/L and elevated FDPs). Leukoerythroblastosis was also present in the peripheral blood smear (Figure 1B). DAT was negative. Chest X-ray was normal, but a CT scan demonstrated interstitial bilateral infiltrates, hepatic lesions suggestive of multiple metastasis and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathies. A gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed, observing an irregularly shaped ulcer with headed up margins whose biopsy was compatible with gastric adenocarcinoma. Bone marrow was infiltrated with neoplastic epithelial cells (Figure 1C). After 48 hours of admission the patient presented multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. As the prognosis was fatal, no life support measures were initiated and the patient died. An autopsy was performed.

Comment

In the 3 cases, anatomopathologic reports revealed gastric adenocarcinoma (2 signet-ring cell type, 1 poorly differentiated type [Case 3]), widespread microscopic metastatic deposits, tumor cell embolism with local thrombosis in the pulmonary arteries and arterioles, and fibrocellular intimal proliferation (Figure 1D-E). Carcinomatous lymphangitis was also present in the autopsies performed (Figure 1F). These findings confirmed the diagnosis of PTTM secondary to microscopic tumor cell embolism due to disseminated gastric adenocarcinoma.

DISCUSSION

PTTM is a rare clinicopathologic entity named by Von Hervay in 1990,23 but first described by Brill and Robertson in 1937 with the term “subacute cor pulmonale”.1 Although detailed pathogenesis remains to be clarified, it seems that embolization of tumoral cells into the pulmonary vessels induce endothelial damage and create a procoagulant environment with local activation of coagulation and fibrocellular intimal proliferation, leading to thrombosis and stenosis of vessels, with resulting pulmonary hypertension and MAHA.14,23 Recent reports suggest that vascular endothelial growth factor, tissue factor, and activated alveolar macrophages in the lung via expression of platelet-derived growth factor, may contribute to the onset and/or progression of PTTM promoting fibrocellular intimal proliferation.2,18,24 In addition, systemic activation of coagulation involves the generation of intravascular fibrin and the consumption of procoagulants, leading to DIC.

Although PTTM has been observed in 0.9% to 3.3% of autopsy case studies with extrathoracic malignancies,14,23 only a few cases are diagnosed antemortem.11,14 Different neoplasms have been reported to be associated with PTTM,5,8,23 but adenocarcinomas are the most frequently related. Gastric carcinoma is the most common (up to 26% of the cases described in the literature) followed by breast (21%), prostate (13%), and lung (10%) carcinoma. Although less frequent, PTTM has also been observed in hematologic malignancies such as Hodgkin lymphoma, aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and myeloma.12 Furthermore, a high incidence of PTTM, up to 16.7%, has been described in the context of gastric carcinomas (3.3% in malignant tumors in general).10 It is not well known why gastric carcinoma is more frequently associated with PTTM than other neoplasms. Interestingly, our 3 patients came from Latin American countries and were younger than most of the patients at gastric cancer diagnosis. Although the higher incidence of gastric cancer is described in Asian countries, such as Japan and Korea, a high incidence has also been seen in Central and South-America, as two-thirds of this malignancy is produced in developing countries. Median age of patients diagnosed with gastric cancer is around 50–70 years. However, several authors have described that patients with gastric cancer and cancer-related MAHA12 or PTTM3 are younger, regardless of their country of origin. There have also been described cases of PTTM associated with gastric cancer in children and adolescent patients, although the prevalence of gastric cancer in young generations is much lower.9

Patients with PTTM can present with different symptoms (weakness, weight loss, pain, fever, and respiratory symptoms)6,8,14 and can mimic different syndromes such as pulmonary hypertension, right heart failure,6,19 or organ dysfunction. In some cases, including the patients reported herein, MAHA and TMA are the predominant features of the clinical scenario, and differential diagnosis with TTP is then mandatory. Current diagnostic criteria of TTP include thrombocytopenia and MAHA without another apparent etiology.7 However, these clinical features are nonspecific and can be observed in other clinical conditions, including PTTM, inducing an inappropriate indication of plasma exchange therapy. It has been described that up to 3% of patients diagnosed with TTP (and almost 7% of the “idiopathic” cases) are really misdiagnosed MAHA secondary to a disseminated malignancy, whose main pathologic mechanism is microthrombi formation by tumor cells.5 When these microthrombi affect predominantly (but not only) pulmonary vessels and produce respiratory signs and symptoms, we call this entity PTTM. Thereby, although occult malignancy causing MAHA may be uncommon (George8 et al described 65 cases of systemic malignancies associated with MAHA and TMA in 30 years), it is important to consider it in the evaluation of patients with TTP.

The cases in the current series reflect that PTTM and TMA due to disseminated malignancy present some atypical clinical and laboratory features that may help in the differential diagnosis.5,15 One of the main differences is the presence of pulmonary involvement. Typically TTP has been reported to spare the lungs. However, one should not consider that all TTP cases with lung involvement are due to PTTM. Actually, pulmonary affectation in TTP is more common than generally appreciated: lung diseases can be the cause of a secondary TTP (pneumonia, chemotherapy-induced lung toxicity); and the lung can be involved in idiopathic TTP due to microthrombotic occlusion of pulmonary vessels or intraparenchymal hemorrhage associated with thrombopenia.16 There exist other features that are different in PTTM compared with TTP: a longer duration of symptoms, moderate thrombocytopenia, higher serum LDH levels, and abnormal coagulation tests. Regarding the levels of ADAMTS-13, it has been described that PTTM cases present a slight decrease instead of the severe deficient activity (<5%) typically seen in idiopathic TTP.4,22 Leukoerythroblastosis in peripheral blood smear and increase of alkaline phosphatase could be indicative of bone marrow infiltration. The detection of lymphadenopathies in the CT images is also a common finding in PTTM. Finally, failure to response to plasma exchange is another characteristic of these patients.5,8

Differential diagnosis with PTTM should be considered not only in atypical TTP, but also in other conditions that may present with fulminant MAHA and could mimic a similar scenario, such as DIC or Trousseau syndrome. About one-third of patients with cancer-related MAHA show laboratory signs indicative of DIC, although malignancies can cause TMA without coagulation abnormalities.12 Trousseau syndrome consists of migratory thrombotic events that precede the diagnosis of an occult visceral malignancy or appear concomitantly with the tumor. It is consequence of multiple pathophysiologic mechanisms that contribute to the hypercoagulability associated with cancer, often occurring with mucin-positive carcinomas although it may be associated with other different types of cancer.20 It has been considered by some authors as a chronic or compensated DIC in the set of malignancy, where there is a slower rate of consumption of coagulation factors and platelets because liver and bone marrow are largely able to replenish them, so thrombosis manifestations are frequent rather than bleeding events. The typical clinical picture is venous and arterial microthrombi with secondary MAHA and that may also be associated with alteration of coagulation tests. However, in recent times, Trousseau syndrome is also used to describe any thrombotic complication associated with cancer, and usually affects large or medium vessels resulting in migratory thrombophlebitis, nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis, arterial emboli or deep vein thrombosis associated or not with DIC,17 differently from the clinical course of PTTM, where the principal location of the microvascular metastases is the lung. There are also physiopathologic differences, as Trousseau syndrome represents a spectrum of disorders, ranging with thrombosis induced primarily by the production of tissue factor by tumor cells, and platelet-rich microthrombotic process triggered by carcinoma mucins and other mechanisms that leads to thrombin generation and fibrin deposition, whereas the main problem in PTTM are the cancer cells embolism, mainly in the pulmonary microcirculation.20

Although pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale are classical signs documented in several case reports, they were not present in our patients. Actually, right ventricle enlargement or hypertrophy appears in less than 50% of patients with PTTM.6,21 Moreover, in the series of Von Herbay et al,23 11/21 patients with PTTM died due to causes different that right cardiac failure. Essentially, patients with MAHA due to metastatic cancer have TMA not only in the lung, but also in other organs.8,13 Therefore, in our opinion, the term PTTM should be considered as part of a more generalized picture (“tumor thrombotic microangiopathy”) with TMA due to micrometastasis in the vessels of diverse organs leading to different possible clinical presentations.

Although most of the cases are diagnosed in autopsies, if systematic malignancy is suspected, bone marrow biopsy, as well as biopsies of any suspected involved organs, would be appropriate.5

There are several reasons to make a prompt diagnosis of the systemic malignancy underlying PTTM. First, it provides an opportunity for treatment with appropriate chemotherapy. Although early recognition of cancer may not benefit these patients since they often have widely disseminated disease, some cases of improvement under treatment have been described.14 Second, the diagnosis allows establishing a prognosis: 90% of patients will die within 1 month, although it will depend on the underlying malignancy.5 Finally, timely diagnosis of systemic malignancy allows not starting or discontinuing plasma exchanges since this treatment is ineffective and can even be counterproductive. Indeed, some authors have hypothesized that plasma exchange might promote microthrombi formation, thereby worsening a chronic compensated state.21

Conclusions

In summary, disseminated malignancy, especially gastric cancer, and PTTM should be suspected in the presence of TMA presenting with atypical characteristics of TTP and/or alteration in coagulation tests, especially with lung involvement. These patients usually need ICU admission and their outcome is rapidly fatal, so they are a medical challenge. Prompt diagnosis is important in order to establish a correct treatment and prognosis, avoiding ineffective therapies.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: aPTT = activated partial thromboplastin time, ADAMTS-13 = a desintegrin and metalloprotease with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13, CT = computed tomography, DAT = direct antiglobulin test, DIC = disseminated intravascular coagulation, FDPs = fibrin degradation products, ICU = intensive care unit, LDH = lactate dehydrogenase, LOS = length of stay, MAHA = microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, NHL = non-Hodgkin lymphoma, PT = prothrombin time, PTTM = pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy, TMA = thrombotic microangiopathy, TTP = thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Financial support and conflicts of interest: The authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brill IC, Robertson TD. Subacute cor pulmonale. Arch Intern Med. 1937; 60:1043–1057. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chinen K, Kazumoto T, Ohkura Y, et al. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy caused by gastric carcinoma expressing vascular endothelial growth factor and tissue factor. Pathol Int. 2005; 55:27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chinen K, Tokuda Y, Fujiwara M, et al. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy in patients with gastric carcinoma: an analysis of 6 autopsy cases and review of the literature. Pathol Res Pract. 2010; 206:682–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fontana S, Gerritsen H, Hovinga JK, et al. Microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia in metastasizing malignant tumors is not associated with severe deficiency of the von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease. Br J Haematol. 2001; 113:100–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francis KK, Kalyanam N, Terrel DR, et al. Disseminated malignancy misdiagnosed as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: a report of 10 patients and a systematic review of publised cases. Oncologist. 2007; 12:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavin MC, Morse D, Partridge AH, et al. Breathless. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George JN. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. New Engl J Med. 2006; 354:1927–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George JN. Systemic malignancies as a cause of unexpected microangiopathic haemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia. Oncology. 2011; 25:908–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hara A, Ichinoe M, Oqawa T, et al. A microscopic adenocarcinoma of the stomach with pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy in a 17-year-old male. Pathol Res Pract. 2005; 201:457–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hotta M, Ishida M, Kojima F, et al. Pulmonary tumor thombotic microangiopathy caused by lung adenocarcinoma: case report with review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2011; 3:435–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kayatani H, Matsuo K, UVeda Y, et al. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy diagnosed antemorten and treated with combination chemotherapy. Intern Med. 2012; 51:2567–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lechner K, Obermeier HL. Cancer-related microangiopathic hemolytic anemia: clinical and laboratory features in 168 reported cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2012; 111:997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lohrmann HP, Adam W, Heymer B, et al. Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia in metastatic carcinoma. Report of eight cases. Ann Intern Med. 1973; 79:368–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyano S, Izumi S, Takeda Y, et al. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25:597–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oberic L, Buffet M, Schwarzinger M, et al. Reference Center for the Management of Thrombotic Microangiopathies, et al. Cancer awareness in atypical thrombotic microangiopathies. Oncologist. 2009; 14:780–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panoskaltsis N, Derman MP, Perillo I, et al. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in pulmonary-renal syndromes. Am J Hematol. 2000; 65:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sack GH, Levin J, Bell WR. Trousseau's sybdrome and other manifestations of chronic disseminated coagulopathy in patients with neoplasms: clinical, pathophysiologic, and therapeutic features. Medicine (Baltimore). 1977; 56:1–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakashita N, Yokose C, Fuji K, et al. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy resulting from metastasic signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach. Pathol Int. 2007; 57:383–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Systrom DM, Mark EJ. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 19-1995. A 55-year-old woman with acute respiratory failure and radiographically clear lungs. N Engl J Med. 1995; 332:1700–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varki A. Trousseau's syndrome: multiple definitions and multiple mechanisms. Blood. 2007; 119:1723–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vasko R, Koziolek M, Fuzesi L, et al. Fulminant plasmapheresis-refractory thrombotic microangiopathy associated with advanced gastric cancer. Ther Apher Dial. 2010; 14:222–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vesely SK, George JN, Laammle B, et al. ADAMTS13 activity in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome: relation to presenting features and clinical outcomes in a prospective cohort of 142 patients. Blood. 2003; 102:60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Von Hervay A, Illes A, Waldherr R, et al. Pulmonary tumor thrombotic microangiopathy with pulmonary hypertension. Cancer. 1990; 66:587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yokomine T, Hirakawa H, Ozawa E, et al. Pulmonary thrombotic microangiopathy caused by gastric carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2010; 63:367–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]