Abstract

Orbital emphysema is generally recognized as a complication of orbital fractures involving any paranasal sinuses. The recognition about its etiology has extended beyond sole trauma, but few articles mentioned tumors to be a possible cause.

In this case report, we present a patient with orbital emphysema associated with ethmoid osteoma without orbital cellulitis or trauma history. The patient developed sudden proptosis, eyelid swelling, and movement limitation of the left eye, peripheral diplopia, and left periorbital crepitus after a vigorous nose blowing.

Complete surgical resection of ethmoid osteoma followed by repair of the orbital medial wall was performed with assistance of combined endoscopy and navigational techniques. Twelve-month follow-up showed no residual lesion or recurrence; the orbital medial wall was accurately repaired with good visual function and facial symmetry.

Tumors should be considered for differential diagnosis of orbital emphysema, and combined endoscopy and navigational techniques may improve safety, accuracy, and effectiveness of orbital surgeries.

INTRODUCTION

Orbital emphysema is generally recognized as a complication of orbital fractures involving any paranasal sinuses. It is usually benign and self-limited, but can lead to ophthalmic emergencies like ischemic optic neuropathy and central retinal artery occlusion.1,2 The recognition about its etiology has extended beyond sole trauma, but few articles mentioned tumors to be a possible cause. Cecire et al3 reported a case of ethmoid osteoma associated with orbital cellulitis and orbital emphysema. Jack et al4 reported a case of frontal sinus osteoma presenting with orbital emphysema after nasal blunt trauma. We hereby present a patient with both ethmoid osteoma and orbital emphysema, who underwent total surgical resection of the osteoma followed by successful repair of the medial wall defect with the assistance of combined endoscopy and navigation techniques. To the authors’ knowledge, it is the first case that revealed an interesting association between ethmoid osteoma and orbital emphysema without orbital cellulitis or trauma history, and adopted combined techniques of endoscopy and navigation to assist the surgical resection of the osteoma. We believe the case is inspiring for both the differential diagnosis of orbital emphysema and the surgical strategy of paranasal sinus osteoma. And we further educated readers about the growth characteristics, symptoms, complications, diagnosis, and therapeutic options of osteomas.

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old woman developed sudden proptosis and eyelid swelling of the left eye, double vision, and left periorbital crepitus after a vigorous nose blowing, but there is no blurry vision, ophthalmalgia, or headache. The patient denied any trauma or infection history. The patient's visual acuity was 8/10 in the left eye and 10/10 in the right. On examination, she was found with peripheral diplopia, exophthalmometry of 15-mm Oculus Dexter (OD) and 18-mm Oculus Sinister (OS), and eyeball movement limitation (Figure 1A). A suspected diagnosis of orbital emphysema was made. Orbital computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed subcutaneous and orbital emphysema, but further revealed a high-density, well-circumscribed mass in the left ethmoid sinus and orbit, which highly indicated an osteoma (Figure 1B). Epinephrine nasal spray and prophylactic antibiotics were prescribed. And she was told to avoid nose blowing, sneezing, and Valsalva maneuvers, and come to see the doctor if symptoms got worse or new symptoms like vision reduction, ophthalmalgia, or headache occurred. The proptosis and swelling gradually relieved within 3 days, but the diplopia and eye movement limitation remained. After extensive discussion of the risks and benefits of surgery, such as bleeding, infection, scar, recurrence, and aggravated diplopia, the patient agreed to proceed with surgical excision of the osteoma and orbital wall repair with the assistance of combined endoscopy (0, 4-mm diameter; STORZ Tricam sl II, Tuttlingen, Germany) and navigational techniques (BrainLAB, Feldkirchen, Germany) under general anesthesia. Approval was obtained from the institute's ethics committee, and the study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and patient consent was obtained.

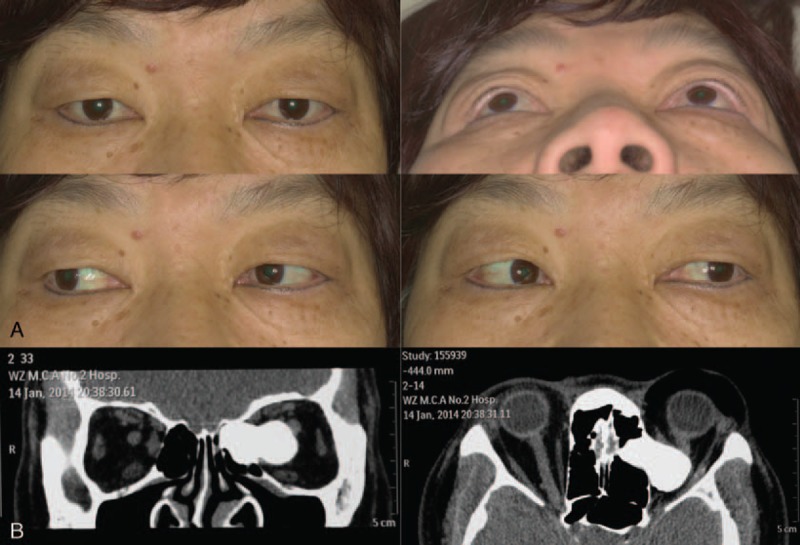

FIGURE 1.

Preoperatively, the patient presented with proptosis of the left eye, swelling of the left periorbital area, and eye movement limitation at the horizontal direction (A), and coronal and axial computed tomography scans showed left orbital emphysema and an ethmoid osteoma extending into the left orbit (B).

Transconjunctival and transcaruncular incisions were made, followed by meticulous dissection between the mass and surrounding normal tissues. The combined endoscope and navigation system (CENS) were used to check whether the dissection was sufficient to completely expose the lesion (Figure 2A). A grey–white, well-demarcated, and lobulated osteoma was then resected, measuring 30 × 20 × 15 mm (Figure 2B). Examine the medial wall defect with CENS. A preformed titanium mesh was implanted to repair the orbital medial wall through the transconjunctival incision. Examine the position of the implant with CENS, and make adjustments until the actual position of the implant was in accordance with the preoperative plan (Figure 2C, D). The incisions were closed with 8–0 absorbable sutures (Vicryl, Johnson & Johnson, NJ). Pathological examination confirmed the tumor was a mixed type of osteoma with mature, ivory, and osteoblast-like features (HE staining, 100×, Figure 3A–C). The last follow-up was 12 months after surgery. The patient acquired an uneventful recovery with good visual function and mid-facial appearance (Figure 4A). The postoperative CT showed no sign of residual tumor and precisely reconstructed medial wall of the left orbit (Figure 4B).

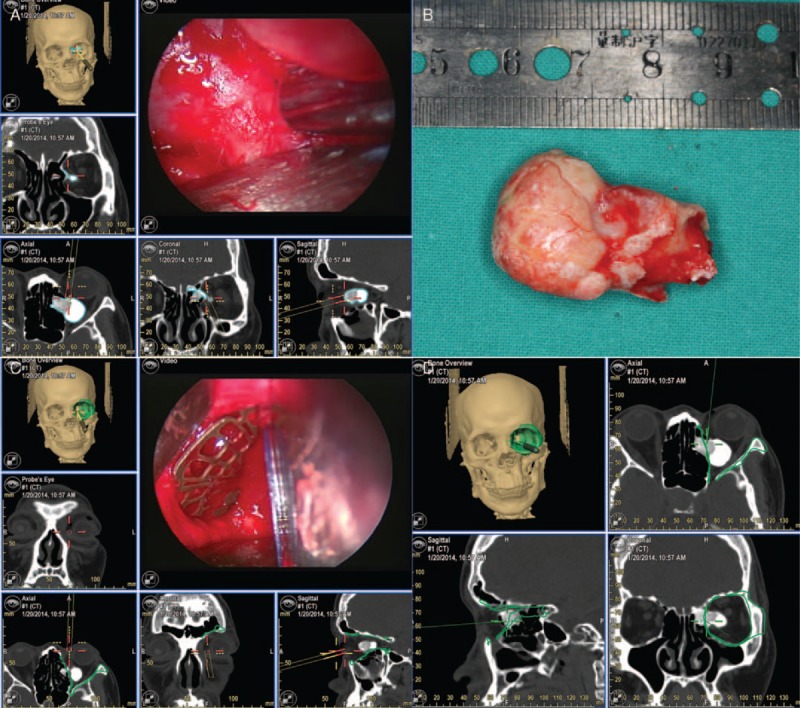

FIGURE 2.

Intraoperatively, the combined endoscope and navigation system (CENS) were used to real-time monitor the dissection and exposure of the lesion (A). The grey–white, and well-demarcated osteoma was completely resected, measuring 30 × 20 × 15 mm (B). The CENS was used to guide and monitor repair of the medial wall with preformed titanium mesh, and examine whether the position of implant accorded with the preoperative plan (C, D).

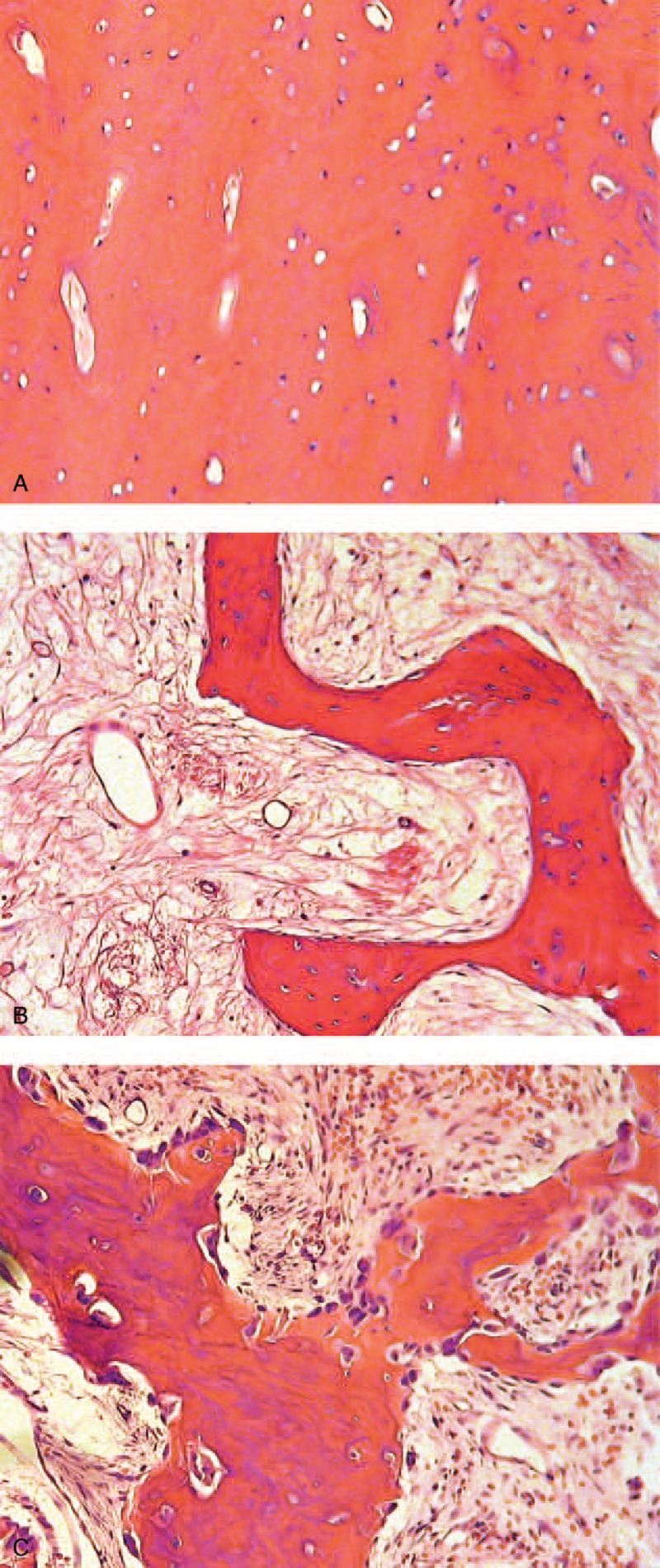

FIGURE 3.

Pathological examination confirmed the tumor is a mixed type of osteoma: The orbital part is ivory-type, mainly composed of mature dense lamellar bone and less stroma (A); the ethmoid part is mature-type, composed of broad trabeculae of mature lamellar bone and collagenous stroma, where a small amount of fibroblasts lie (B); and the characteristic osteoblastoma-like area demonstrates abundant osteoblasts and scattered osteoclasts at the margins of the woven bones, and more cellular and vascular stroma (C). (HE staining, 100×).

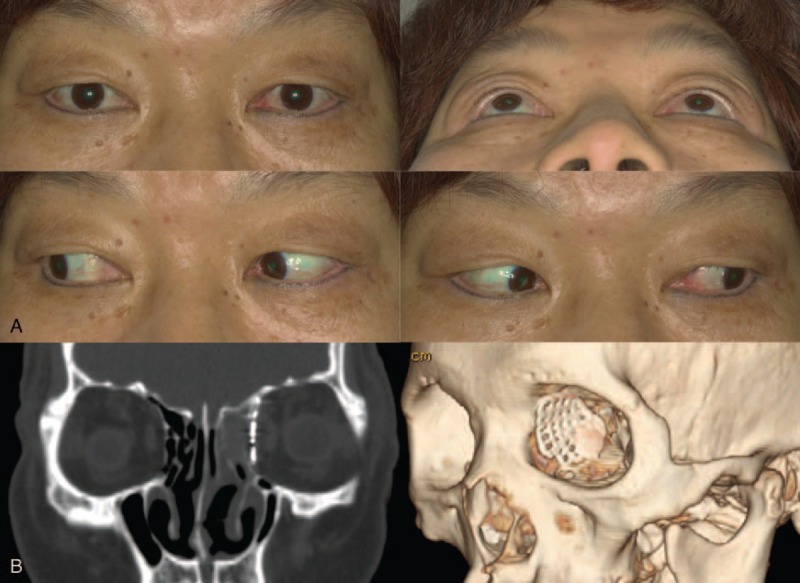

FIGURE 4.

Twelve-month follow-up showed no residual lesion or recurrence, and the patient acquired complete elimination of proptosis, periorbital swelling, and ocular motion restriction and accurately repaired orbital medial wall with no complications (A, B).

DISCUSSION

Although severe consequence like blindness is possible, orbital emphysema is generally benign and self-limited, most associated with orbital fracture involving paranasal sinuses.1 Other causes include but are not limited to pulmonary barotrauma, infection, conjunctival laceration, and oral and otorhinolaryngeal procedures.1,5 Roselle and Herman1 reported a case with no aforesaid conditions but a possibly undetectable anatomical defect. Few authors mentioned tumor as an etiology, except Cecire et al's3 reported case indicating a possible association of ethmoid osteoma with orbital emphysema and orbital cellulitis, and Jack et al's4 reported case of frontal sinus osteoma presenting with orbital emphysema after nasal blunt trauma. In our case, we easily reached a probable diagnosis of orbital emphysema by taking history, but finding an ethmoid osteoma and its interesting association with orbital emphysema was unexpected. This was the third case representing the association between orbital emphysema and paranasal sinus osteoma, but to the authors’ knowledge, it is the first one involving no orbital cellulitis or trauma history, which made the association more direct and convincible. The osteoma eroded the lamina papyracea and extended into the orbit, establishing a channel between the orbit and the ethmoid sinus; when the patient had a vigorous nose blowing, the fast increased intranasal pressure pushed air into the orbit, leading to proptosis and periorbital swelling.

Osteoma is the most common neoplasm of paranasal sinuses, benign, and generally slow-growing.6–8 Enough attention should be put for its possible encounter by ophthalmologists, ear, nose, and throat (ENT) surgeons as well as neurological surgeons, and the treatment may need close operation of a professional and multidisciplinary team. It can be asymptomatic, whereas sometimes presents with sinusitis, headache, facial pain, seizures and orbital symptoms like ophthalmalgia, diplopia, metamorphopsia, global displacement, dacryocystitis, orbital cellulitis, and vision loss. Uncommon but likely severe complications include pneumocephalus, intracranial mucocele, optic nerve compression, and cerebrospinal fluid leaks etc.6,7 Most osteomas remain undetected, and may be diagnosed incidentally on radiographs. The indication of surgical intervention remains controversial, but when it causes symptoms or complications, grows fast, or extends to adjacent orbital and cranial cavities, the surgical removal is preferred. The surgical route and mode are chosen under comprehensive consideration of the size, site, growth rate of the tumor, related risks, and the treatment process may need cooperation of different divisions. Both open and endoscopic approaches can acquire satisfying outcomes.6 Sometimes imposed radical tumor resection is related to unavoidable damages to adjacent vital structures, so we performed surgery with the assistance of combined endoscopy and navigational techniques, which enables real-time monitor of the osteoma and other vital structures in the orbit, complete resection of the osteoma without iatrogenic injuries, and true-to-original repair of the orbital medial wall. Whether surgery is performed or not, continued follow-up is necessary to observe the development or recurrence of the tumor.

In conclusion, tumors can be a cause of orbital emphysema and should be considered for differential diagnosis. The clinical decision and treatment may need close cooperation of a multidisciplinary team. Combined endoscopy and navigational techniques may improve safety, accuracy, and effectiveness of orbital surgeries.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: OD = oculus dexter, OS = oculus sinister, CT = computed tomography, ENT = ear, nose, and throat, CENS = combined endoscope and navigation system.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grant (81170876), Shanghai Municipal Hospital Emerging Frontier Technology Joint Research Project (SHDC12012107), Shanghai Science and Technology Commission Research Project (12441903003, 124119a9300).

XF has full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The study has no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed.

Design and conduct of the study (AZ, XF); data collection, analysis and interpretation (AZ); navigation technology support (AZ, YL); manuscript preparation and review (AZ, ML, WS); surgery performance (XF, ML, WS); Decision to submit the manuscript for publication (XF).

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roselle HA, Herman M. A hearty sneeze. Lancet 2010; 376:1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee SL, Mills DM, Meyer DR, et al. Orbital emphysema. Ophthalmology 2006; 113:2113.2111–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cecire A, Harrison HC, Ng P. Ethmoid osteoma, orbital cellulitis and orbital emphysema. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1988; 16:11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jack LS, Smith TL, Ng JD. Frontal sinus osteoma presenting with orbital emphysema. Ophthalm Plast Reconstruct Surg 2009; 25:155–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan K, Winchell GD. Orbital emphysema from nose blowing. N Engl J Med 1968; 278:1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pons Y, Blancal JP, Verillaud B, et al. Ethmoid sinus osteoma: diagnosis and management. Head Neck 2013; 35:201–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McHugh JB, Mukherji SK, Lucas DR. Sino-orbital osteoma: a clinicopathologic study of 45 surgically treated cases with emphasis on tumors with osteoblastoma-like features. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2009; 133:1587–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buyuklu F, Akdogan MV, Ozer C, et al. Growth characteristics and clinical manifestations of the paranasal sinus osteomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011; 145:319–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]