Abstract

Parastomal variceal bleeding is a rare complication of portal hypertension, which often occurs in a recurrent manner and might be life-threatening in extreme situations. Treatment options vary, and no standard therapy has been established.

Herein, we report 2 such cases. The first patient suffered from parastomal variceal bleeding after Hartmann procedure for rectal cancer. Stomal revision was performed, but bleeding recurred 1 month later. The second patient developed the disease after Miles procedure for rectal cancer. Embolization via the percutaneous transhepatic approach was performed using the Onyx liquid embolic system (LES) (Micro Therapeutics Inc, dba ev3 Neurovascular) in combination with coils, and satisfactory results were obtained after a 4-month follow-up.

Our cases illustrate that surgical revision should be used with caution as a temporary solution due to the high risk of rebleeding, whereas transhepatic embolization via the Onyx LES and coils could be considered a safe and effective choice for skillful managers.

INTRODUCTION

Ectopic varix is a rare complication of portal hypertension that can arise along the entire gastrointestinal tract but that seldom arises at the stomas.1 Variceal bleeding from a stoma, which can be observed in patients with intestinal and colonic stomas or those with ileal conduit urinary diversion, has rarely been reported.2 Persistent bleeding can lead to repeated hospital admissions and numerous blood transfusions. The management varies from simple measures such as local compression and sclerotherapy to more invasive methods such as stomal revision and portosystemic shunts. Other options include embolization via a transhepatic, transjugular transhepatic, or direct percutaneous route, placement of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and transplantation of the liver. We present 2 cases of ectopic variceal bleeding from colonic stomas in an attempt to draw lessons from the treatment experience. To our knowledge, this is also the first report of the Onyx liquid embolic system (LES) (Micro Therapeutics Inc, dba ev3 Neurovascular) being successfully used to treat parastomal varices.

CASE 1

Patient Information

A 71-year-old male patient was admitted to our tertiary hospital on July 26, 2001, for recurrent episodes of hemorrhage from a transverse colonic stoma. The intermittent bleeding, which could spontaneously stop or be stopped by compression, had lasted for 4 weeks before admission, with 2 to 3 episodes per week and 50 to 200 mL of blood lost each time. Previously, the patient had been diagnosed with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and had undergone colectomy 3 times due to multiple metachronous colon cancers in 1977, 1985, and 1996, respectively. In April 2001, the patient was diagnosed with rectal cancer, and Hartmann procedure with transverse colostomy was performed. During his last hospitalization, the patient experienced an episode of hematemesis. Hepatic cirrhosis complicated with esophageal varices was then confirmed after gastrointestinal contrast and ultrasound examinations.

Clinical Findings

The vital signs were stable at admission, and physical examination showed nothing abnormal, except for ecchymoses around the stoma.

Diagnostic Focus and Assessment

The patient was anemic (hemoglobin, 80 g/L), with a normal coagulation profile. Ultrasonic imaging revealed a normal-sized liver with uneven echogenicity, a mildly enlarged spleen, and a widened portal vein trunk measuring 1.3 cm. Abundant variceal vessels were also revealed by ultrasound; therefore, variceal bleeding from the stoma caused by portal hypertension was highly suspected.

Therapeutic Intervention and Follow-Up

A stomal revision surgery with careful suture ligation of all of the visible varices was then performed. The postoperative recovery was uneventful, and no stomal bleeding occurred during hospitalization. However, the bleeding recurred 1 month later and occurred intermittently thereafter. On December 7, 2002, the patient suffered from a massive hemorrhage, with a blood loss of approximately 400 mL. He was severely anemic (hemoglobin, 65 g/L) and received a blood transfusion at our emergency room. The patient was lost to follow-up thereafter.

CASE 2

Patient Information

A 78-year-old male patient who presented with a 4-month history of dizziness and recurrent stomal bleeding was admitted to our hospital on July 15, 2014. The bleeding could be stopped by local compression, but it worsened, with more frequent episodes and more massive hemorrhages. The most dangerous hemorrhage, with a blood loss of approximately 1500 mL, occurred 5 weeks before the patient was admitted. He suffered from severe anemia, with a hemoglobin level of 58 g/L, which required an emergency blood transfusion. One year prior, the patient had undergone abdominal perineal resection with sigmoid colostomy (Miles procedure) for rectal cancer.

Clinical Findings

The patient's vital signs were stable at admission, and physical examination showed an anemic appearance and a normal colonic stoma in his left lower abdomen.

Diagnostic Focus and Assessment

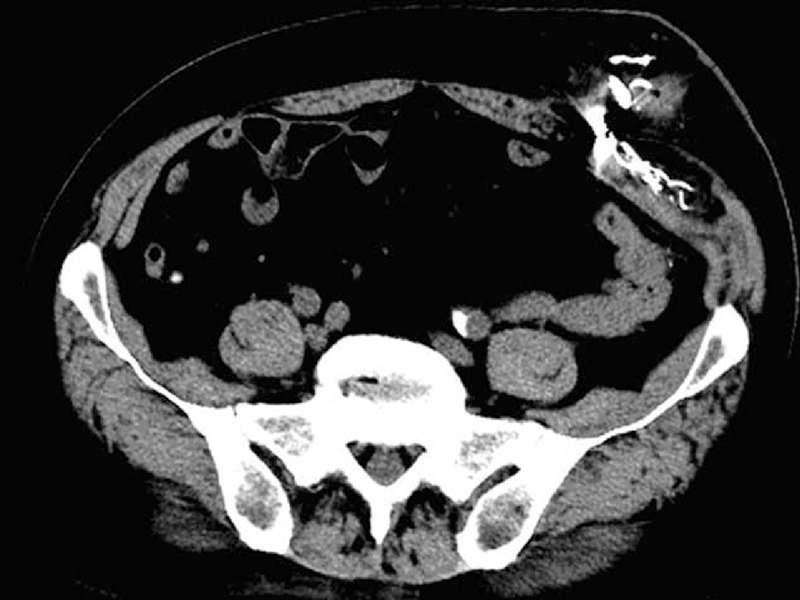

A contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed large ectopic varices around the colostomy site (Figure 1). In addition, splenomegaly and broadened veins of the portal system were observed. Because no definitive cause, including liver cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and portal thrombosis or Budd–Chiari syndrome, could be identified, the patient was diagnosed with idiopathic portal hypertension. Portal venography via the percutaneous transhepatic approach demonstrated that the varices arose from the inferior mesenteric vein (Figure 2A–B). Retrograde flow toward the stoma that communicated with the abdominal and ilioinguinal veins as well as coexisting esophageal varices were also revealed.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan demonstrated ectopic varices at parastomal site (arrows). CT = computed tomography.

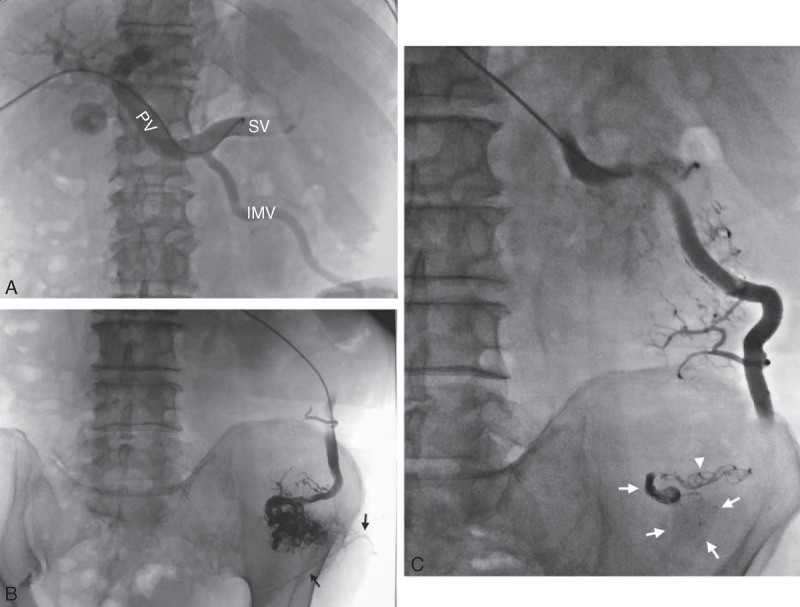

Figure 2.

(A) Percutaneous transhepatic portal venography revealed widened portal vein trunk, spleen vein, and IMV. (B) Venography showed a complex network of parastomal variceal vessels arising from the IMV. Communicating veins to systemic circulation can be noticed (arrows). (C) Embolization using Onyx LES (arrows) in combination with coils (arrowheads) via transhepatic approach. IMV = inferior mesenteric vein, LES = liquid embolic system, PV = portal vein trunk, SV = spleen vein.

Therapeutic Intervention and Follow-Up

Ectopic varices were embolized using a combination of coils and the Onyx 18 LES (Figure 2C). After the operation, an obvious shrinkage of the stoma was observed, and the patient's sensation of swelling around the stoma disappeared. An additional CT scan demonstrated complete occlusion of the parastomal varices (Figure 3). The patient had an uneventful recovery and was doing well at the 4-month follow-up, without the recurrence of stomal bleeding.

Figure 3.

Postembolization nonenhanced CT scan confirmed a complete occlusion of the variceal vessels. CT = computed tomography.

DISCUSSION

Parastomal varices are confirmed to be portosystemic venous communications that occur in portal hypertension patients when the retrograde flow from the high-pressure portal venous system decompresses into the low-pressure systemic veins of the abdominal wall via the mucocutaneous venous network surrounding the stoma site.2,3 The high pressure of the portal vein system forces abnormal dilatation of the communicating veins, leading to the clinical presentation of varices. Parastomal varices can spontaneously bleed in a repeated manner, and it is estimated that 3% to 5% of all patients with the dual pathology of portal hypertension and stoma formation will develop significant morbidity associated with bleeding.4

The standard therapy for parastomal variceal bleeding has not yet been established.4–8 Stomal revision, which is aimed to disconnect the mucocutaneous portosystemic communications, is one of the options; however, an unsatisfactory result was obtained using this method in our first case. The main cause is likely newly developed or reconnected venous collaterals shortly after the operation. Local surgical procedures such as stoma revision and resitting of the stoma should be used with caution, as these procedures are invasive, carry a high risk of postoperative morbidities, and are associated with a high rebleeding rate of up to 81%.4,9

Percutaneous transhepatic embolization (PTE) has long been confirmed as a good treatment option.10,11 Although PTE can potentially be associated with an increased risk of several complications such as hepatic bleeding, bile leakage, and portal thrombosis,12 it is relatively safe for skillful managers. However, a proportion of patients do rebleed after PTE because the abnormal variceal veins can recanalize. To minimize the occurrence of rebleeding, we performed a precise embolization in our second case using the Onyx LES in combination with coils.

Onyx is a nonabsorbable and nonadhesive liquid embolic agent that can be delivered downstream and is uniquely able to occlude small and distal vessels. The safety and efficacy of Onyx have been proven in treating aneurysms, pseudoaneurysms, and arteriovenous fistulas,13,14 but its employment in the embolization of parastomal varices has not yet been reported. With a long precipitation time and high visibility under fluoroscopy, Onyx allows for precise control and results in more complete embolization of the varices and tiny tributaries. Thus, in the second case, the Onyx LES was employed at distal sites to adequately fill small mucocutaneous varices. For the proximal major varix, the use of coils also achieved a good occlusive effect. Theoretically, the recurrence of varices due to incomplete embolization or recanalization could be minimized by employing the Onyx LES. Practically, this method was proven to be safe and effective over a short follow-up of 4 months. Observations of a longer follow-up period and more cases are required to further evaluate the effect of this method.

TIPS could decrease the portal pressure at the stoma site and has been considered as a successful means with a relatively low rebleeding rate.4,7,8 However, considering the much higher cost, as well as the underlying damage to the liver function, this procedure was not employed for our second patient, who exhibited only a relatively early stage of portal hypertension.

CONCLUSIONS

Among the various treatment modalities for parastomal variceal bleeding, surgical revision should be used with caution because it is only a temporary solution with a high risk of rebleeding. PTE with the Onyx LES and coils, which is less invasive than TIPS or other surgical procedures, is safe and effective and possesses a relatively wide indication for skillful managers. It could be used for patients treated for the first time, as well as for patients for whom other procedures failed. As it causes little damage to liver function, it is also suitable for patients with decompensated liver function.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: Onyx LES = Onyx liquid embolic system, TIPS = transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, CT = computed tomography.

LW and J-lZ are the first authors who contributed equally to the article.

All interventions given were part of normal health care, and thus, ethical approval was neither obliged nor sought. However, approvals from the patients were obtained to publish the case reports.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almadi MA, Almessabi A, Wong P, et al. Ectopic varices. Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 74:380–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yao DH, Luo XF, Zhou B, et al. Ileal conduit stomal variceal bleeding managed by endovascular embolization. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19:8156–8159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwok AC, Wang F, Maher R, et al. The role of minimally invasive percutaneous embolisation technique in the management of bleeding stomal varices. J Gastrointest Surg 2013; 17:1327–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pennick MO, Artioukh DY. Management of parastomal varices: who re-bleeds and who does not? A systematic review of the literature. Tech Coloproctol 2013; 17:163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helmy A, Kahtani AIK, Fadda AIM. Updates in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Hepatol Int 2008; 2:322–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arulraj R, Mangat KS, Tripathi D. Embolization of bleeding stomal varices by direct percutaneous approach. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2011; 34:S210–S213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nayar M, Saravanan R, Rowlands PC, et al. TIPSS in the treatment of ectopic variceal bleeding. Hepatogastroenterology 2006; 53:584–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrafiello G, Laganà D, Giorgianni A, et al. Bleeding from peristomal varices in a cirrhotic patient with ileal conduit: treatment with transjugular intrahepatic portocaval shunt (TIPS). Emerg Radiol Mar 2007; 13:341–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naidu SG, Castle EP, Kriegshauser JS, et al. Direct percutaneous embolization of bleeding stomal varices. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2010; 33:201–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samaraweera RN, Feldman L, Widrich WC, et al. Stomal varices: percutaneous transhepatic embolization. Radiology 1989; 170:779–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kishimoto K, Hara A, Arita T, et al. Stomal varices: treatment by percutaneous transhepatic coil embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1999; 22:523–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toumeh KK, Girardot JD, Choo IW, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic embolization as treatment for bleeding ileostomy varices. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1995; 18:179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jadhav AP, Pryor JC, Nogueira RG. Onyx embolization for the endovascular treatment of infectious and traumatic aneurysms involving the cranial and cerebral vasculature. Neuro Intervent Surg 2013; 5:562–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu YC, Newman CB, Dashti SR, et al. Cranial dural arteriovenous fistula: transarterial Onyx embolization experience and technical nuances. J Neurointerv Surg 2011; 3:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]