Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Abstract

In the spectrum of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCL), both T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (TCHRBCL) and most lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LG) cases are characterized by the relative rarity of the neoplastic B-cell population, with respect to the overwhelming non-neoplastic counterpart of T cells or histiocytes. Here we report a case of aggressive B-cell lymphoma with unusual clinicopathological features partially overlapping these two entities.

The patient was a previously healthy 55-year-old male, presenting with a computed tomography finding of a pelvic mass, inguinal lymphadenopathies, and pulmonary nodules. Two excisional lymph node biopsies resulted inconclusive for lymphoproliferative disease. Because of a colonic perforation, the patient underwent an urgent laparotomy, which disclosed a large pelvic abscess. The pathological examination of the surgical specimen could not discriminate between a primary aggressive B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder and an abnormal inflammatory hyper-reaction. The patient developed a septic state, not resolving until death, which occurred because of an abdominal hemorrhage. A second perimortem surgical specimen consisting of a nodal mass revealed a diagnosis of an Epstein–Barr virus-negative high-grade large B-cell lymphoma with massive necrosis, angiocentric pattern of growth, and prominent T-cell infiltrate.

The unique clinicopathological features did not allow to classify this tumor within any of the recognized WHO entities, potentially representing a new clinicopathological variant of DLBCL in-between TCHRBCL and LG.

INTRODUCTION

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL), accounting for approximately 30% of all newly diagnosed cases and more than 80% of aggressive lymphomas.1 It has become increasingly recognized that DLBCL is not one entity, but rather a heterogeneous group of disorders, characterized by a wide variety of immunomorphologic characteristics, genetic features, and clinical outcomes.2 In the spectrum of DLBCL, both T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (TCHRBCL) and most lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LG) cases are characterized by the relative rarity of the neoplastic B-cell population, with respect to the overwhelming background of non-neoplastic surrounding T-cells or histiocytes.

TCHRBCL usually occurs in younger patients and often involves the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. Several morphological, immunophenotypic, and molecular similarities exist between TCHRBCL and nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin's lymphoma, which may pose serious diagnostic challenges.3 In TCHRBCL less than 10% neoplastic B cells are seen on a background rich in reactive histiocytes and T cells, with a phenotype of cytotoxic nonactivated lymphocytes (CD8+, TIA+, granzyme B−). Large neoplastic cells are CD20+ and CD79+, often express Bcl-6, and have immunoglobulin genes rearranged and mutated, supporting a germinal center B-cell derivation; however, infrequent expression of CD10, absence of BCL-2, and gene expression profiling data suggest that some downregulation of the B-cell program has occurred.4,5 Variations in morphology and immunophenotype are common, calling into question whether TCHRBCL is a homogeneous disease entity.6

LG is an angiocentric and angiodestructive process involving extranodal sites, composed of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-positive B cells admixed with reactive T cells, which frequently predominate. LG typically presents in the fifth decade; lung involvement is the most frequent, followed by central nervous system, skin, liver, and kidney.7

Here, we report a case of aggressive B-cell lymphoma with unusual clinicopathological features, partially overlapping these two entities and potentially representing a clinicopathological variant of DLBCL not previously described.

METHODS

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa. Immunohistochemical stainings were done using routine methods for clinical diagnosis; sections were submitted to antigen retrieval in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid 1 mmol/L (pH 8.0) by microwaving twice for 5 minutes at either 750 or 900 W. Details of the antibodies used are shown in Table 1. Bound antibodies were visualized by the alkaline phosphatase antialkaline phosphatase complexes technique.8

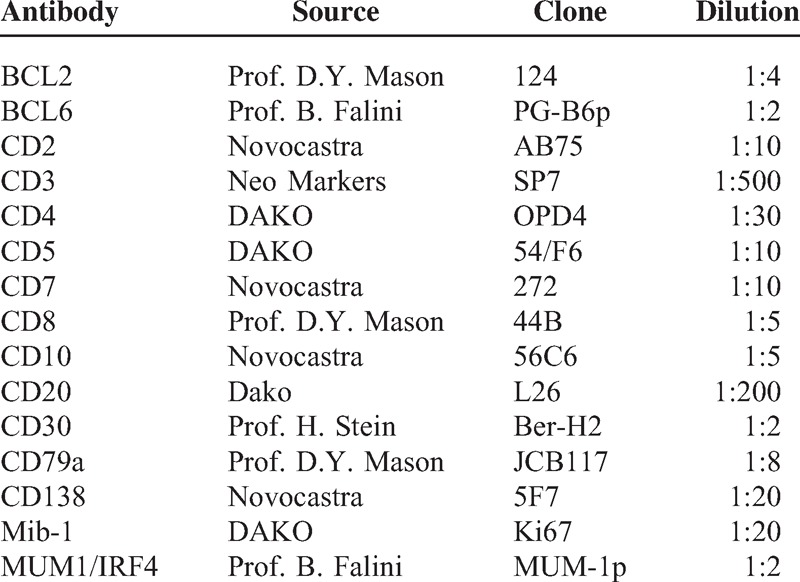

TABLE 1.

Antibodies Used in This Study

EBV was detected using an ISH probe against EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER) (EBER PNA Probe/FITC, Dako Cytomation, Carpenteria, CA) d according to the manufacturer's instructions.9

Analysis for B- and T-cell clonality by immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) and T-cell receptor gamma (TRG@) gene rearrangement was performed according to established polymerase chain reaction protocols for clinical use.10

Ethical approval was not necessary for this study, as all the procedures and interventions illustrated in this case are part of the good clinical practice. The patient expressed written informed consent to all diagnostic and therapeutic procedures described thereby.

CASE REPORT

A 55-year-old white male was referred to our outpatient clinic because of a computed tomography (CT) finding of a large abdominal mass and left inguinal adenopathy. No significant medical history was reported. At our evaluation, he reported a remittent and dull pain on his left flank, which had prompted a further diagnostic evaluation by his general practitioner. Laboratory values were notable for mild anemia (Hb = 13.1 g/dL; normal range, 14–16 g/dL), moderate lymphopenia (620/mm3, normal range, 1000–3500/mm3), and raised serum creatinine levels (1.7 mg/dL). Serum LDH levels were normal (348 U/L, normal range, 100–450 U/L), as serum electrophoresis and liver function. The CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed multiple scattered nodular lesions in the lungs (the greater of which measured 1.6 cm); marked left hydronephrosis was present, caused by a diffuse thickening of the pelvic connective tissue, compressing the left ureter and surrounding the bladder, the prostate, and ileopsoas muscles. Multiple left inguinal adenopathies were evident, the larger of which measured 2.6 cm. A biopsy of the most accessible inguinal lymph node had been performed, but no evidence of malignant lymphoma was found at histological examination. Given the strong clinical suspicion for a neoplastic disease, a new biopsy of the largest inguinal adenopathy was performed, which exhibited fat necrosis and chronic granulomatous inflammation with giant cells. At the positron emission tomography (PET) scan, both the pelvic masses and the pulmonary nodules showed remarkable metabolic avidity to 18-FDG (Fig. 1). A diagnostic bone marrow biopsy was proposed, but the patient refused the procedure. After these tests and before a new clinical evaluation, the patient developed acute abdominal pain with fever and was hospitalized in a nearby local clinic. An urgent laparotomy was performed. Intraoperative examination did not confirm the finding of an intraabdominal mass seen at the CT scan; a large pelvic abscess was instead found, with evidence of colonic perforation, bladder-colonic fistula, and completely necrotic bladder. Large adenopathies were also absent. Surgical intervention included partial colonic, total bladder, and omental resection with terminal colostomy to the left side, suturing of the remaining bladder, and fashioning of a bilateral nephrostomy. All the surgical specimens were submitted for pathological examination.

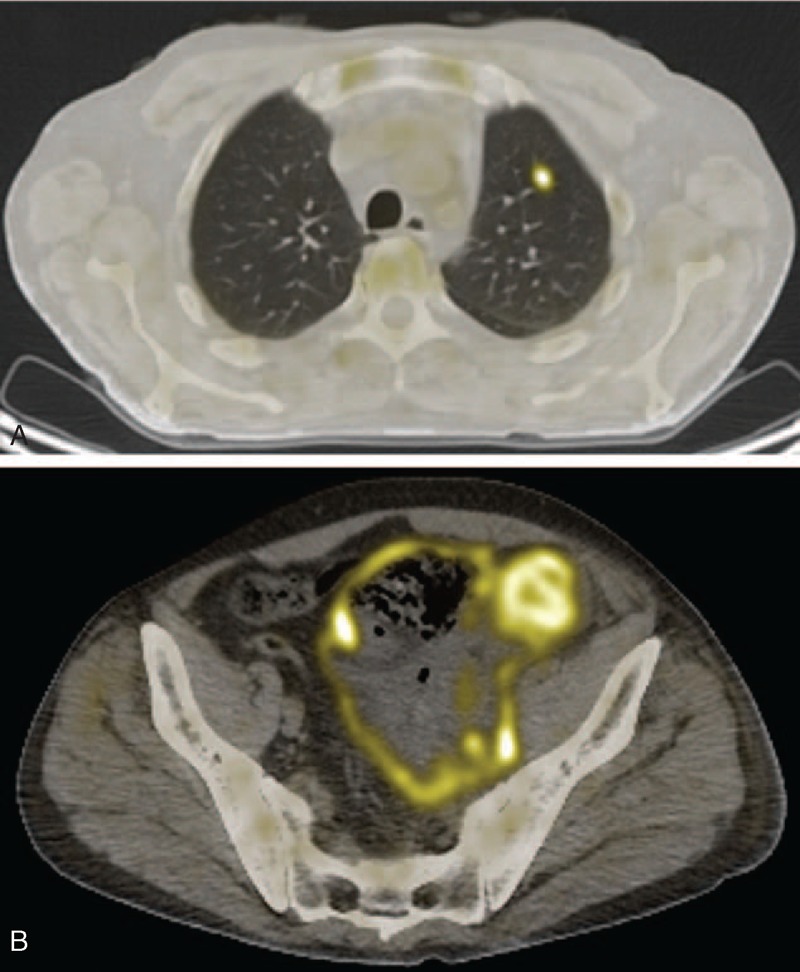

FIGURE 1.

Fusion positron emission tomography/computed tomography images showing metabolic uptake of the pulmonary nodules (A) and of the pelvic mass (B).

Pathological Findings of the First Surgical Specimen

Grossly, the intestinal wall appeared thickened and hardened with a 3-cm large perforation. The cut surface was whitish with areas of frank necrosis and the overlying mucosa featured erosions and ulcerations. The bladder wall appeared extensively necrotic.

On histology, the intestinal submucosa and muscularis propria layer displayed a mild small lymphocytic infiltrate within an edematous and necrotic stroma, with scattered atypical mononuclear larger cells, sometimes provided with a conspicuous nucleolus and a relatively abundant cytoplasm. In the intestine, the large cells were B lymphocytes (CD20+/CD79a+/CD3−) with strong IRF4 expression and active cycling (Ki67 80%). No clear-cut expression of germinal center markers (BCL6 and CD10), CD30, BCL2, and κ or λ light chains could be observed, although no positive internal controls were present for BCL6. The immunohistochemical staining for cytomegalovirus and in situ hybridization (ISH) for EBER proved negative. The accompanying population of small lymphocytes was mainly composed of CD3+ cells with both helper (CD4+) and cytotoxic (CD8+) phenotype, and rare CD20+ B cells (Fig. 2). T lymphocytes did not display evident cytological abnormalities; regular representation of other T-cell markers (CD2, CD5, CD7; Fig. 3) was observed; molecular studies for clonal rearrangement of TCR-gamma gene proved negative (Supplementary Fig. 1S, http://links.lww.com/MD/A126). Molecular studies for clonal rearrangement of IgH gene did not provide any reliable result, likely because of the abundant coagulative necrosis and tissue autolytic degeneration. The specimen from the bladder showed extensively necrotic tissue with scattered lymphoid infiltration and no evidence of large atypical cells.

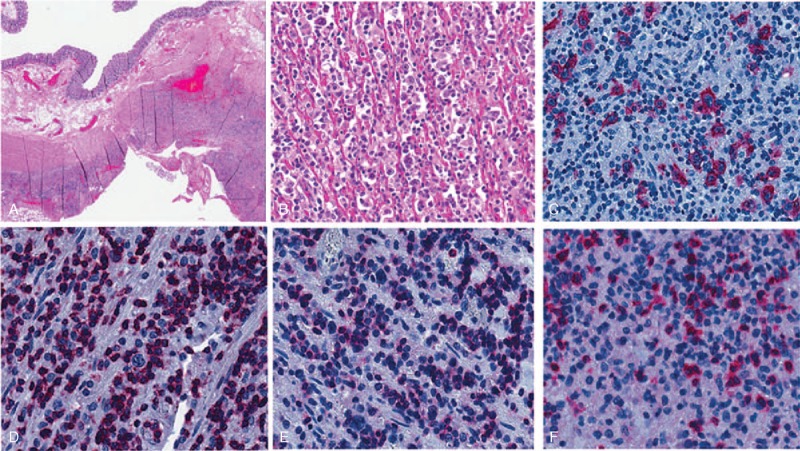

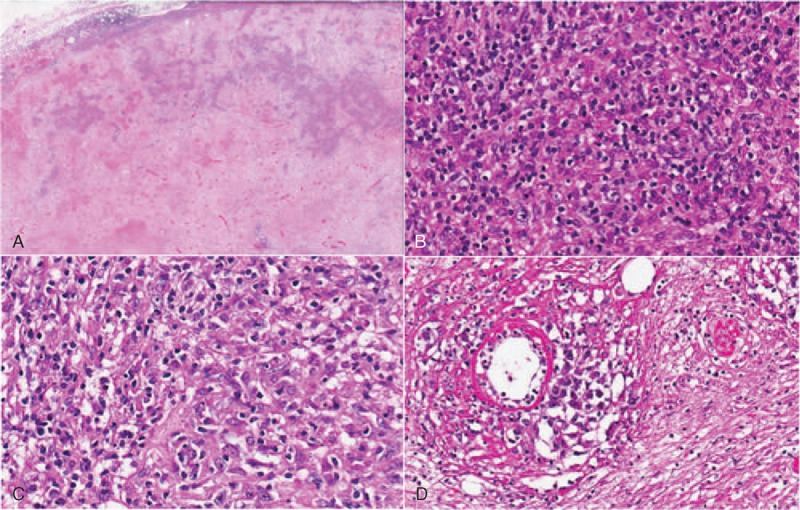

FIGURE 2.

Microscopic features of the colonic lesions: (A) the intestinal lesion is depicted associated with a marked lymphoid infiltrate in the wall and necrosis in the perivisceral fat (H&E); (B) at higher power, the infiltrate is composed mainly of small lymphocytes and scattered large cells (H&E); the large blasts are CD79a-positive B cells (C), whereas most of small lymphocytes are CD3+ T cells (D), positive for both CD4 (E) and CD8 (F; alkaline phosphatase antialkaline phosphatase immunostaining).

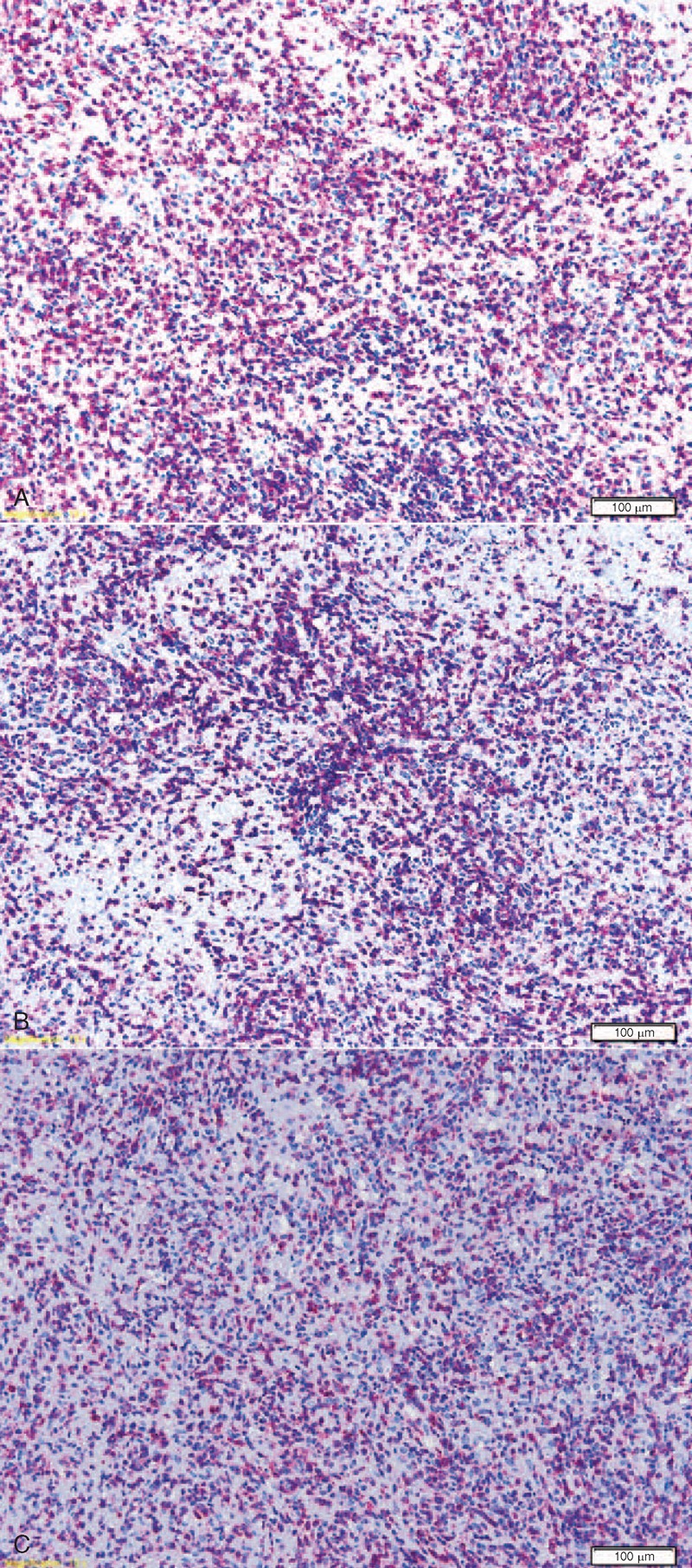

FIGURE 3.

Immunohistological features of the lymphocytic infiltrate in the colonic lesions, mainly composed of T cells: regular representation of CD2 (A), CD5 (B), and CD7 (C) is observed.

The histological and immunohistochemical features of the lymphoid infiltrate prompted the differential diagnosis between a primary aggressive B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder and an abnormal inflammatory hyper-reaction with secondary perforation and involvement of the colonic and bladder wall, in the light of the referred absence of a properly defined mass at surgical examination and presence of a large abscess instead.

After the intervention, the patient entered a septic state confirmed by repeated findings of Gram-negative bacteria from blood and abdominal drainage cultures. Notwithstanding extensive antibacterial treatment, the septic state persisted. The finding of increasing pulmonary nodules at the chest CT scan prompted the execution of a transbronchial biopsy of a 3-cm nodular lesion in the left lung, which resulted nondiagnostic. Also, pleural fluid obtained from thoracentesis proved sterile, and cytological examination of the sediment did not find cells. Given the strong suspicion for B-cell lymphoma, the resistance to multiple antibacterial treatments, and the evidence for growing abdominal and pulmonary lesions, the possibility of a treatment with Rituximab was discussed. However, owing to the poor clinical conditions, the patient was deemed unfit even for this treatment.

Approximately 2 months after the hospitalization, the patient developed a massive intra-abdominal hemorrhage. He underwent immediate surgical intervention, but attempt to stop the bleeding was unsuccessful. The patient died during the intervention. A large mass in the left iliac fossa was found and sent for pathological examination (Figs. 4 and 5).

FIGURE 4.

Nodal lymphoma: (A) the lymph node shows large areas of necrosis; (B–D) where preserved, the infiltrate exhibits areas morphologically similar to the intestinal infiltrate and areas with numerous blasts and angiotropism.

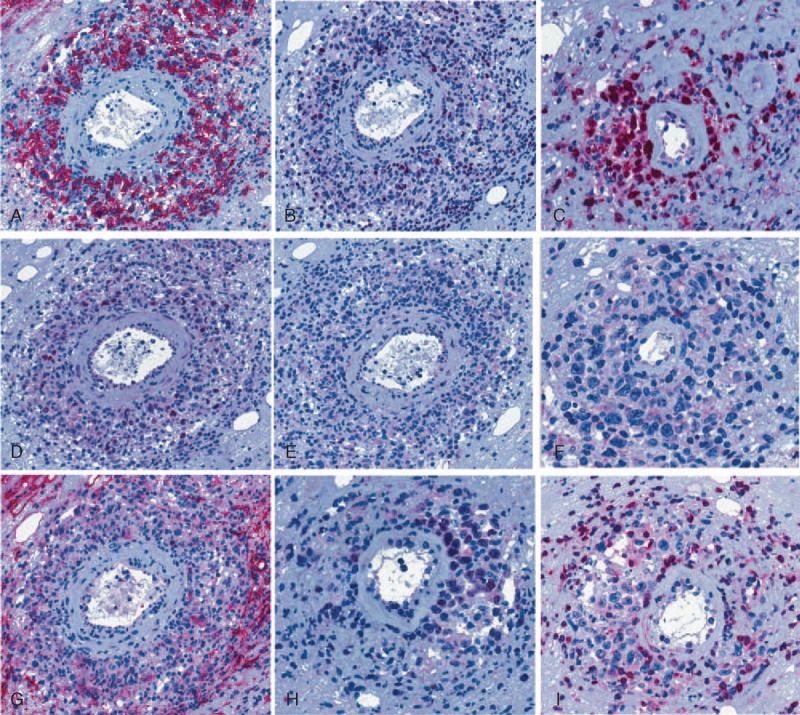

FIGURE 5.

Immunohistochemical features of the nodal lymphoma: the neoplastic cells express CD20 (A), MUM1/IRF4 (B) and c-myc (D), with focal positivity for Bcl-6 (H); a high proliferative index is demonstrated by Ki67 immunostaining (C); also, the large atypical blasts proved negative for CD138 (E), CD30 (F), CD10 (G), and for BCL2 (I).

Pathological Findings of the Second Surgical Specimen

On histology, the sample was diffusely necrotic and edematous, with a dispersed loose mixed lymphocytic and granulocytic inflammatory infiltrate within which large cells, cytologically more atypical than those previously observed in the intestine, were seen, either scattered singly or focally surrounding small blood vessels as perivascular cuffs. These cells expressed CD20, IRF4, and BCL6, with negativity for CD3, CD10, and BCL2. The strong diffuse positivity for the c-Myc protein (>90%) and the extremely high Ki67-index confirmed the aggressive nature of the neoplastic process. Again, ISH for EBER proved negative and the clonal rearrangement of IgH genes was not assessable.

A diagnosis of an extranodal EBV-negative high-grade large B-cell lymphoma with massive necrosis and angiocentric pattern of growth was addressed, although the unique histological features did not allow to classify this tumor within any of the recognized WHO entities.

DISCUSSION

From a clinicopathological perspective, this neoplasm cannot be easily attributed to a definite WHO category and poses the following diagnostic challenges. The presence of scattered large B-cells in a small T-lymphocytic background suggested a T-cell-rich large B-cell lymphoma of the intestinal wall as the only possible lymphoma diagnosis, although the wide necrosis and edema as well as the CD4 prevalence of the T-cell infiltrate and the extranodal site were scarcely consistent. The abundant necrosis and the prominent perivascular location of the neoplastic cells (particularly observed in the second excised sample) may conversely suggest a diagnosis of LG grade 37,11 even without detectable EBV integration. The latter observation might be justified by the poor DNA preservation, likely induced by the wide necrosis; also, rare cases of EBV integration with discordant EBER (ISH) and latent membrane protein (LMP) (immunohistochemistry) positivity have been described; in these instances, PCR for EBV BamHI-W fragment yielded the highest sensitivity12 However, the clinical setting strongly discourages the diagnosis of LG, as this tumor usually presents in immunocompromised subjects and mostly affects lungs (>90% of cases),11 whereas our patient was immunocompetent and fully healthy just a couple of months prior, and the lesion primarily arose in the gastrointestinal tract. The alternative diagnosis of a TCHRBCL, already considered in the first biopsy, could only fit with the presence of scattered EBV-negative large B-blasts,13 as neither the massive necrosis nor the striking angiotropism, the large cell sheets, and the scarcity of T lymphocytes are consistent. Very rarely, cases of angiotropic TCHRBCL have been reported, but only as primary skin lymphomas;14,15 however, in these cases, the angiotropic component was represented by the small T-cells, the B blasts being found at distance from the blood vessels.14,15 As regards phenotype, the significant aggressiveness of the tumor is unusual in a BCL2-negative neoplasm, this anti-apoptotic molecule being among the parameters commonly related to a worse prognosis.16,17 However, this result is fairly in keeping with the remaining phenotype of the tumor, which is reminiscent of a late germinal center B lymphocyte (being BCL6+/IRF4+), as more reliably assessed in the second biopsy. However, since none of the several immunohistochemical algorithms published for stratifying the large B-cell lymphomas upon the cell of origin18,19 is accepted or advised by the WHO classification and because the patient's conditions did not allow any therapy, no speculations are feasible regarding the prognostic impact of the phenotype.

From a clinical viewpoint, the management of the patient has been prejudiced by failure to reach a definite histological diagnosis before death. Overall, the patient underwent two lymph node biopsies, a transbronchial biopsy, and a surgical intervention without a conclusive diagnosis, but these unsuccessful attempts likely recognize different causes. The absence of a pathological PET uptake in the residual inguinal lymph nodes suggests that lymphoma cells were truly absent or poorly represented in the excised samples. The sensitivity of fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of TCHRBCL is low.20 In the first surgical specimen, the massive necrosis prevented the molecular studies for clonality to exclude an exaggerated inflammatory reaction. When necrosis is established before tissue removal, little can be done to improve the diagnostic accuracy, as cellular detail is irreparably lost and most immunostaining and molecular techniques either fail or give misleading results.21 Moreover, after the surgical procedure, the patient went into a septic state, which persisted until the exitus, precluding any further immunosuppressive or cytostatic treatment.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this case represents the first reporting of a massively necrotizing angiotropic EBV-negative large B-cell lymphoma, with a fatal clinical course, primarily arising in the gastrointestinal tract of an immunocompetent previously healthy middle age man.

This study has been supported by AIL (Associazione Italiana contro le Leucemie) of Ancona-Italy.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography, DLBCL = diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, EBER = EBV-encoded small RNA, EBV = Epstein–Barr virus, Hb = hemoglobin, IgH = immunoglobulin heavy chain, ISH = in-situ hybridization, LG = lymphomatoid granulomatosis, NHL = non-Hodgkin lymphomas, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, PET = positron emission tomography, TCHRBCL = T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma, TCR = T-cell receptor, WHO = World Health Organization.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Website (www.md-journal.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO Classification of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th edLyon: IARC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martelli M, Ferreri AJ, Agostinelli C, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2013; 87:146–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris NL. Shades of gray between large B-cell lymphomas and Hodgkin lymphomas: differential diagnosis and biological implications. Mod Pathol 2013; 26 suppl 1:S57–S70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marafioti T, Mancini C, Ascani S, et al. Leukocyte-specific phosphoprotein-1 and PU.1: two useful markers for distinguishing T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma from lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin's disease. Haematologica 2004; 898:957–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brune V, Tiacci E, Pfeil I, et al. Origin and pathogenesis of nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma as revealed by global gene expression analysis. J Exp Med 2008; 205:2251–2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dogan A, Burke JS, Goteri G, et al. Micronodular T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma of the spleen: histology, immunophenotype, and differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol 2003; 27:903–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colby TV. Current histological diagnosis of lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Mod Pathol 2012; 25 suppl 1:S39–S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sabattini E, Bisgaard K, Ascani S, et al. The EnVision++ system: a new immunohistochemical method for diagnostics and research—critical comparison with the APAAP, ChemMate, CSA, LABC, and SABC techniques. J Clin Pathol 1998; 51:506–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu TC, Mann RB, Epstein JI, et al. Abundant expression of EBER1 small nuclear RNA in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. A morphologically distinctive target for detection of Epstein-Barr virus in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded carcinoma specimens. Am J Pathol 1991; 138:1461–1469. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Dongen JJ, Langerak AW, Brüggemann M, et al. Design and standardization of PCR primers and protocols for detection of clonal immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene recombinations in suspect lymphoproliferations: report of the BIOMED-2 Concerted Action BMH4-CT98-3936. Leukemia 2003; 17:2257–2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pittaluga S, Wilson WH, Jaffe ES. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC; 2008. 247–249. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qi ZL, Han XQ, Hu J, et al. Comparison of three methods for the detection of Epstein-Barr virus in Hodgkin's lymphoma in paraffin-embedded tissues. Mol Med Rep 2013; 7:89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Wolf-Peeters C, Delabie J, Campo E. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. T cell/histiocyte rich large B-cell lymphoma. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC; 2008. 238–239. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gogstetter D, Brown M, Seab J, et al. Angiocentric primary cutaneous T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol 2000; 27:516–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfistershammer K, Petzelbauer P, Stingl G, et al. Methotrexate-induced primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with an ’angiocentric’ histological morphology. Clin Exp Dermatol 2010; 35:59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson NA, Slack GW, Savage KJ, et al. Concurrent expression of MYC and BCL2 in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30:3452–3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horn H, Ziepert M, Becher C, et al. MYC status in concert with BCL2 and BCL6 expression predicts outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2013; 121:2253–2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutiérrez-García G, Cardesa-Salzmann T, Climent F, et al. Gene-expression profiling and not immunophenotypic algorithms predicts prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Blood 2011; 117:4836–4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer PN, Fu K, Greiner TC, et al. Immunohistochemical methods for predicting cell of origin and survival in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29:200–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Das DK, Pathan SK, Mothaffer FJ, et al. T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma (TCRBCL): limitations in fine-needle aspiration cytodiagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol 2012; 40:956–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkins BS. Pitfalls in lymphoma pathology: avoiding errors in diagnosis of lymphoid tissues. J Clin Pathol 2011; 64:466–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]