Abstract

The pathophysiology of neutrophilic dermatoses (NDs) and autoimmune connective tissue diseases (AICTDs) is incompletely understood. The association between NDs and AICTDs is rare; recently, however, a distinctive subset of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (LE, the prototypical AICTD) with neutrophilic histological features has been proposed to be included in the spectrum of lupus. The aim of our study was to test the validity of such a classification. We conducted a monocentric retrospective study of 7028 AICTDs patients. Among these 7028 patients, a skin biopsy was performed in 932 cases with mainly neutrophilic infiltrate on histology in 9 cases. Combining our 9 cases and an exhaustive literature review, pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet syndrome (n = 49), Sweet-like ND (n = 13), neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis (n = 6), palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis (n = 12), and histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatitis (n = 2) were likely to occur both in AICTDs and autoinflammatory diseases. Other NDs were specifically encountered in AICTDs: bullous LE (n = 71), amicrobial pustulosis of the folds (n = 28), autoimmunity-related ND (n = 24), ND resembling erythema gyratum repens (n = 1), and neutrophilic annular erythema (n = 1). The improvement of AICTDS neutrophilic lesions under neutrophil targeting therapy suggests possible common physiopathological pathways between NDs and AICTDs.

INTRODUCTION

Neutrophilic dermatoses (NDs) are a group of disorders characterized by skin lesions for which histological examination shows intense inflammatory infiltrate, composed primarily of neutrophils, with no evidence of infection. Classical NDs include Sweet syndrome, pyoderma gangrenosum, subcorneal pustular dermatosis, erythema elevatum diutinum, and other transitional forms. NDs may be associated with a variety of systemic disorders, including myeloproliferative disorders, monoclonal gammopathies (mainly IgA type), inflammatory bowel diseases, and autoimmune connective tissue diseases (AICTDs). At present, the pathophysiology of NDs is poorly understood, but the current knowledge of NDs suggests that they should be categorized within the spectrum of “polygenic” autoinflammatory diseases.1,2 One of the prototype polygenic autoinflammatory diseases is inflammatory bowel disease. The exact term “autoinflammatory disease” encompasses an enlarging group of inflammatory disorders, defined as Mendelian genetic diseases (monogenic diseases) of the innate immune system that involve mutations in molecular platforms called “inflammasomes.” This results in an excessive inflammatory cytokine production by the innate immune cells (in particular, interleukin (IL)-1) in response to danger signals. Monogenic autoinflammatory diseases are also characterized by a clinical and biological inflammatory syndrome in which there is little or no evidence of autoimmunity.3 One of the prototypic monogenic autoinflammatory diseases is the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome, which is caused by NLRP3 selective gene mutations.4 NDs share many clinical features of monogenic inflammatory disorders, including fever, arthralgia, and neutrophilic infiltration of the skin and visceral organs.

Connective tissue diseases (CTDs) are a group of disorders that are characterized by abnormal structure or function of one or more of the elements of connective tissues.5 AICTDs include lupus erythematosus (LE), dermatomyositis (DM), Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic sclerosis. The pathophysiological hallmark of AICTDs is the activation of the adaptive immune system against “self” antigens, resulting in the detection of autoantibodies (autoAbs) (produced by plasmocytes, the most mature state of B cells) or self-antigen-specific T cells. Skin lesions in AICTDs, especially in LE,6 are generally separated into 2 groups, based on a careful morphological evaluation, evolution, and histological results:

Specific skin lesions, which result from autoreactive T lymphocyte infiltrate (sometimes mixed with histiocytes) of the dermis and the basement membrane and/or autoAbs deposition; this is classically associated with vacuolar degeneration of the basal cell layer of the epidermis and apoptotic keratinocytes (interface dermatitis), as is found in LE and DM, but not Sjögren syndrome.

Nonspecific CTD skin lesions, which result from vasculitis, thrombosis, or other mechanisms and may be encountered in other disease settings.

For example, acute, subacute, and chronic cutaneous LE, including discoid LE7 are LE-specific skin lesions; Raynaud phenomenon, purpura, urticarial vasculitis, livedo, and calcinosis cutis are nonspecific LE skin lesions.

Autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases share clinical (fever, skin rash, and arthralgia) and biological (systemic inflammation) characteristics, but the resulting inflammation is mainly due to the activation of the innate immune system in autoinflammation (neutrophils) and the adaptive immune system in autoimmunity (lymphocytes).8 Associations between AICTDs and neutrophilic infiltration have been reported as pyoderma gangrenosum and LE;9 Sweet syndrome and LE,10 rheumatoid arthritis,11 or DM;12 Sweet-like ND and LE;13 neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis and LE;14 nonbullous histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatitis and LE;15 palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis and LE;16 bullous LE;17 ND in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), resembling erythema gyratum repens;18 amicrobial pustulosis of folds and LE;19 autoimmunity-related ND,20 also coined by other authors “nonbullous neutrophilic lupus erythematosus”21 (nonbullous clinical lesions with interface dermatitis and an unusual neutrophilic infiltrate on histological examination). Notably, in 2010, Lipsker22 proposed to include neutrophilic skin lesions in the spectrum of LE skin lesions. The aim of our study was to test the reproducibility and the applicability of this classification in lupus and other AICTDs. Therefore, we describe the clinical and histological spectrum of neutrophilic skin lesions associated with AICTDs through various case reports and through an exhaustive review of the cases that have been published in the literature.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

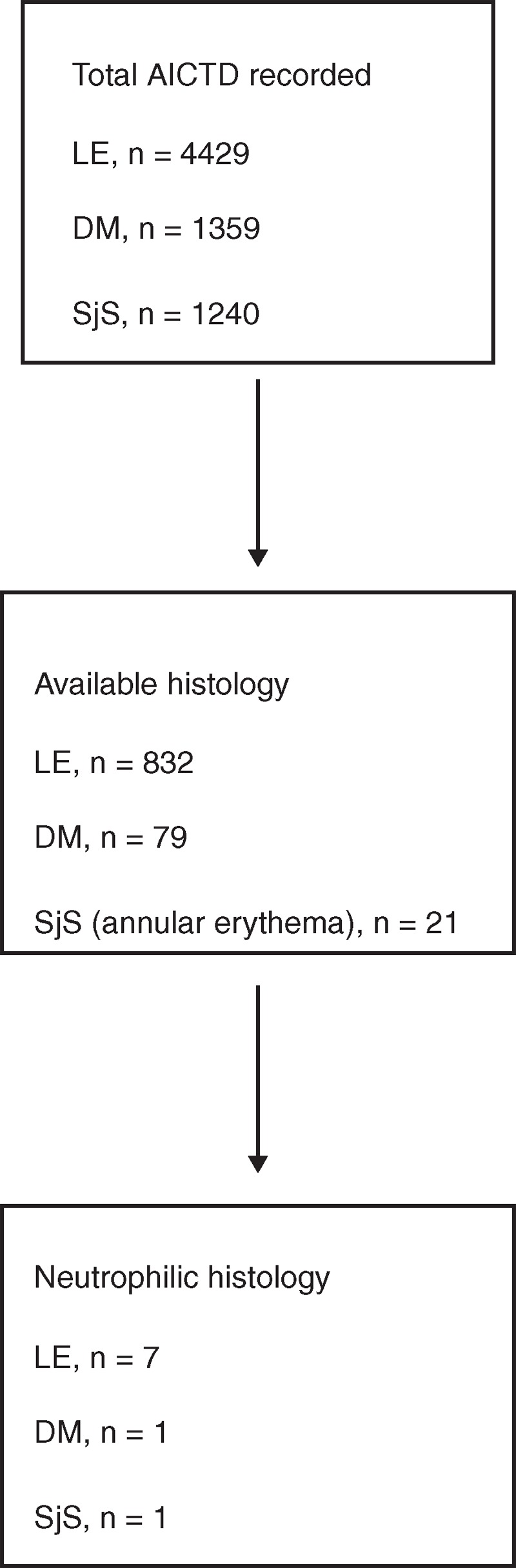

We retrieved the medical records of all AICTDs patients for which skin biopsy showed significant neutrophilic infiltrate; records were examined from Saint Louis Hospital (Paris, France), between 2003 and 2013. Among 7028 AICTDs patients, a skin biopsy was available in 932 cases; there was mainly neutrophilic infiltrate on histology in 9 cases (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of patients with AICTD neutrophilic skin lesions included in the study. AICTD = autoimmune connective tissue disease, DM = dermatomyositis, LE = lupus erythematosus, SjS = Sjögren syndrome.

Patients were included if they met the following criteria:

Diagnosis of AICTD, according to the standard criteria of AICTDs, which is based on the revised 1997 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for SLE.23 The ACR 2012 criteria was used for Sjögren syndrome;24 the Bohan and Peter25 1975 criteria was used for DM. Cutaneous LE diagnosis was based on clinical criteria of discoid LE (red, scaly patches of variable size, which heal with atrophy, scarring, and pigmentary changes), subacute LE (erythematous macules or papules of sun-exposed areas that evolve into scaly, papulosquamous or annular/polycyclic plaques) or LE tumidus (indurated, succulent, urticaria-like, single or multiple plaques with a bright reddish or violaceous smooth surface without clinically visible epidermal involvement on sun-exposed areas, which is exacerbated during the summer), and/or histological characteristic of LE (interface dermatitis with vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer of the epidermis and patchy dermal lymphocytic infiltrate, possibly associated with epidermal atrophy and hyperkeratosis)6 without systemic involvement.

Histological features of neutrophilic skin lesions, including every skin lesion with a significant neutrophilic infiltrate (>50%). Neutrophilic leukocytoclastic vasculitis skin lesions were not included to focus on neutrophilic skin infiltrates that may be related to AICTDs.

Biopsies, medical records, and photographs of patients included were reviewed and analyzed. We also searched the National Library of Medicine's MEDLINE database (Bethesda, MD) for relevant literature using the keywords “neutrophil,” “neutrophilic dermatosis,” “ Sweet syndrome,” “neutrophilic urticaria,” “pyoderma gangrenosum,” “annular erythema,” “palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis,” or “amicrobial pustulosis of the folds,” together with “connective tissue disease,” “discoid lupus erythematosus,” “systemic lupus erythematosus,” “Sjogren syndrome,” “rheumatoid arthritis,” and “dermatomyositis.” The bibliographies of all the selected articles were reviewed for additional case reports. Together, 89 different articles, published between 1978 and 2014 in the international literature, were included in this review.

RESULTS, DISCUSSION, AND LITERATURE REVIEW

A total of 9 patients fulfilled both the histopathological and clinical criteria. A summary of clinical signs and laboratory tests of cases is depicted in Table 1. Pictures of clinical and histological (hematoxylin and eosin stain or direct immunofluorescence, original magnification ×20, ×40, or ×200) skin lesions are shown in Figures 2–11. We also performed a literature review of AICTD-associated NDs cases and discussed the possible pathophysiological link regarding this association. We distinguished, within our cases and literature ND cases, a large clinical and histological spectrum of neutrophilic skin lesions associated with AICTDs. Some of the NDs are likely to occur in both autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases, such as pyoderma gangrenosum; other NDs seem to be specifically encountered in the setting of autoimmunity, such as bullous LE or amicrobial pustulosis of folds. However, the fact that some of the NDs have not been reported in the context of autoinflammatory syndromes does not mean that they do not have an underlying autoinflammatory mechanism. As described below, a better terminology may be required for describing AICTD-associated NDs: Sweet syndrome, Sweet-like ND, and neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis do not always have well-defined boundaries; historically, the term “Nonbullous neutrophilic lupus erythematosus” includes various entities and may be inadequate.21

TABLE 1.

Summary of Clinical Signs and Laboratory Tests of Cases

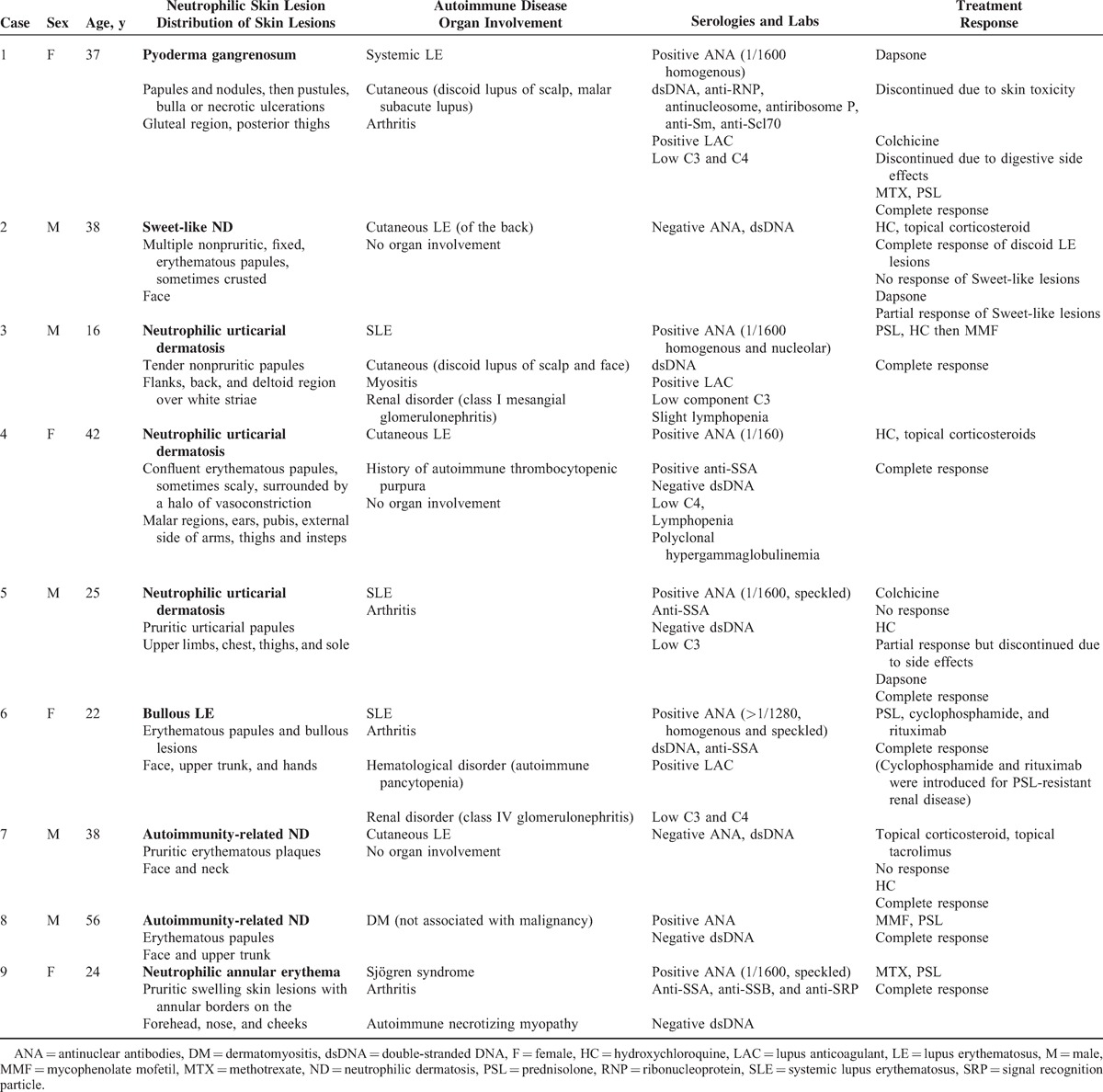

FIGURE 2.

Multiple pyoderma gangrenosum lesions in the context of systemic LE (case 1). LE = lupus erythematosus.

FIGURE 11.

Neutrophilic annular erythema of the cheek in the context of Sjögren syndrome (case 9).

Pyoderma Gangrenosum and SLE

Pyoderma gangrenosum is characterized by painful nodular, bullous, or pustular lesions, which eventually ulcerate. There are no specific histological findings or pathognomonic laboratory tests for diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum. Of monogenic autoinflammatory diseases, pyoderma gangrenosum is associated with an underlying systemic disease in 50% to 70% of cases.26 The underlying diseases primarily include inflammatory bowel diseases, arthritis, IgA monoclonal gammopathies, and myeloid hematological malignancies; however, pyoderma gangrenosum may also occur on its own. Rheumatoid arthritis is the most common AICTD reported in association with pyoderma gangrenosum (10% of cases, in a review of 348 patients afflicted with pyoderma gangrenosum).27 SLE and pyoderma gangrenosum is an uncommon association. Seventeen cases of pyoderma gangrenosum associated with SLE,9,28–41 3 cases associated with Sjögren syndrome,42–44 and 1 case associated with dermatomyositis45 have been reported in the literature. As in our case (case 1, Table 1 and Figure 2), in patients with SLE-associated pyoderma gangrenosum, the occurrence of pyoderma gangrenosum and the response to treatment were correlated with the SLE activity. Similar lesions to pyoderma gangrenosum have also been described in patients with SLE-associated antiphospholipid syndrome.9

Sweet Syndrome and AICTDs

The diagnostic criteria of Sweet syndrome must include both major and 2/4 minor criteria. The 2 major criteria are erythematoedematous plaques or nodules and a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of primary vasculitis, on biopsy. The minor criteria include the following: excellent response to steroid treatment; periods of fever or malaise; preceding nonspecific respiratory or gastrointestinal infection, vaccination, hematoproliferative disorder, solid tumor, pregnancy, or autoimmune disease; increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate.46 Most Sweet syndrome cases are considered to be idiopathic, but Sweet syndrome can be associated with hematological malignancy, solid tumors, and drugs.47 Sweet syndrome also has an association with inflammatory bowel disease (both Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis).1 Among AICTDs, Sweet syndrome has been described in association with rheumatoid arthritis (n = 9),11,48–51 Sjögren syndrome (n = 9),52–57 including a case of coexisting Sjögren syndrome and Crohn disease,57 DM (n = 1),12 undifferentiated AICTD (n = 1),58 and mixed AICTD (n = 1).59 The association of Sweet syndrome with SLE is most commonly reported; it has been reported in 28 cases, including 6 drug-induced cases (hydralazine, n = 460–63; acyclovir, n = 264,65) and 22 cases that often occurred simultaneously with the onset of LE.10,21,51,58,66–78 The skin lesion features may not accurately meet the Sweet syndrome diagnostic criteria; in these cases, a diagnosis of Sweet-like ND has been proposed in the literature (see below).

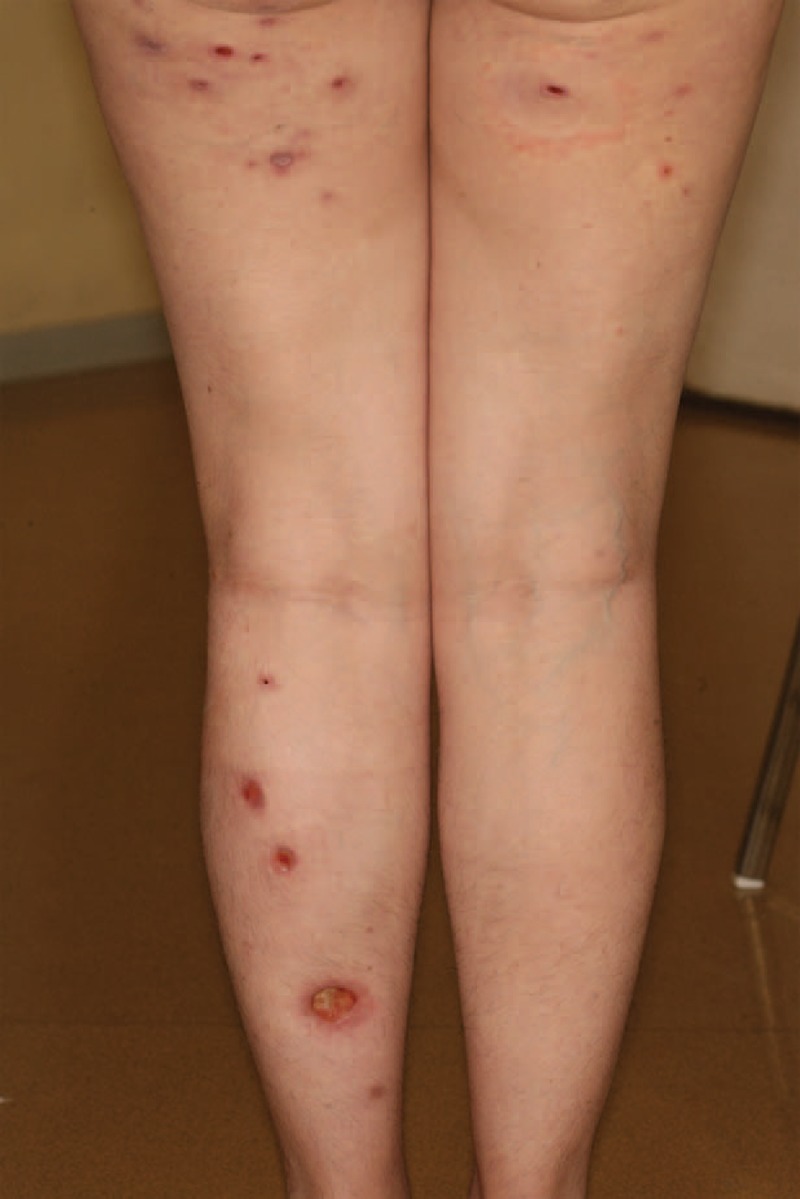

Sweet-Like ND and AICTDs

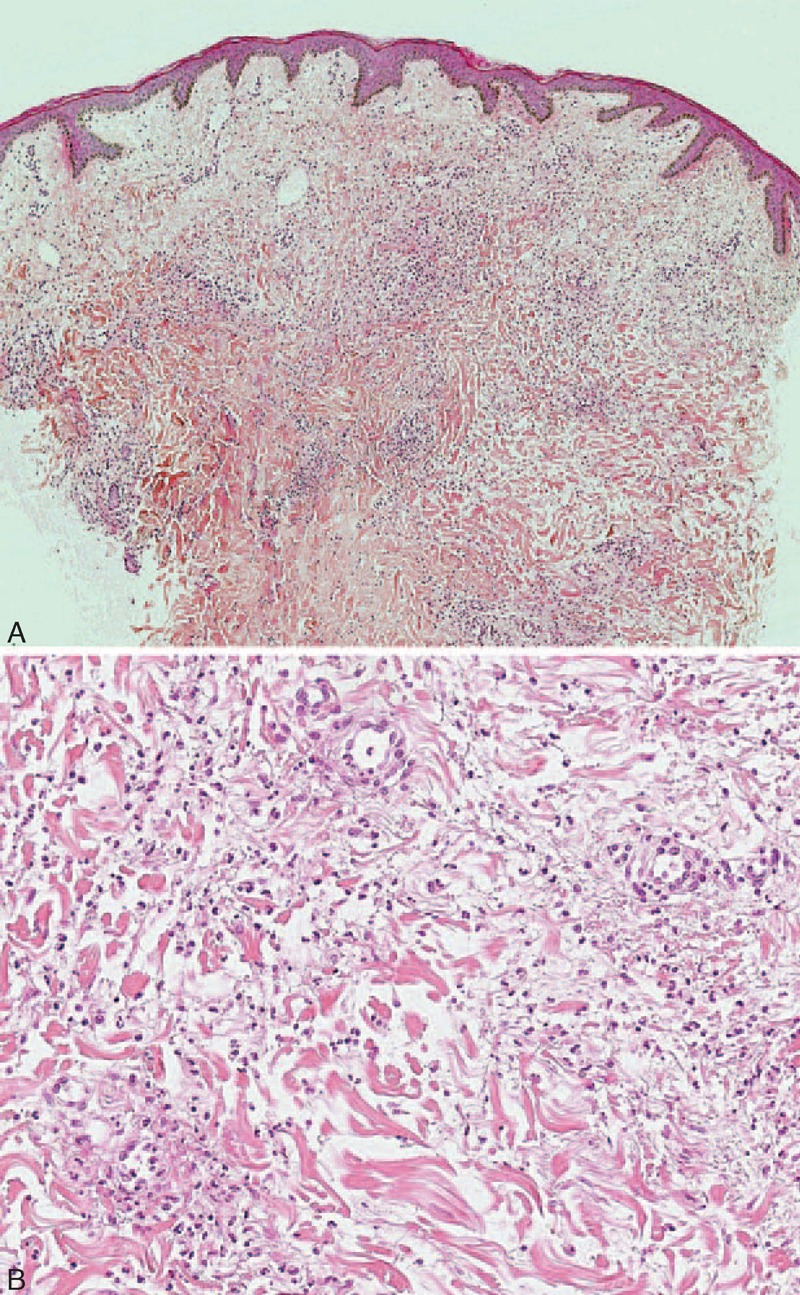

In daily care, as in literature case reports, the difference between Sweet syndrome and Sweet-like ND is not clear. Sweet-like ND is defined as a neutrophil-predominant infiltrate of the dermis with leukocytoclasia and superficial dermal edema. Sweet-like ND should be distinguished from Sweet syndrome because of its subacute or chronic evolution, its occurrence on sun-exposed sites, and the absence of fever or malaise. Unlike typical Sweet syndrome, skin biopsy may also show a moderate neutrophilic infiltrate and a polymorphous leukocytic and lymphocytic infiltrate. The difference between Sweet-like ND and neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis is based on the clinical aspect (macules in neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis vs papules in Sweet-like ND) and the histology (more neutrophilic dermal infiltrates and dermal edema in Sweet-like ND than in neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis).14 Case 2 (Table 1) had both clinical (Figure 3) and histological (Figure 4A and B) features of Sweet-like ND on the face, whereas demonstrating typical discoid LE on the back. Larson and Granter79 reported 14 cases of “Systemic lupus erythematosus–associated neutrophilic dermatosis,” including 6 cases that match the Sweet-like ND description. Together, we found 12 cases of Sweet-like ND associated with LE (case 2 and references13,79). It is likely that Sweet syndrome and Sweet-like ND associated with AICTDs belong to the same entity.

FIGURE 3.

Sweet-like ND of the face in the context of subacute cutaneous LE (case 2). LE = lupus erythematosus, ND = neutrophilic dermatosis.

FIGURE 4.

(A) Dense dermal polymorphic infiltrate composed primarily of neutrophils suggestive of Sweet syndrome (case 2) (hematoxylin–eosin stain; original magnifications, 20). (B) Dense dermal infiltrate primarily neutrophilic with edema suggestive of Sweet syndrome (case 2) (hematoxylin–eosin stain; original magnifications, 200).

Histiocytoid Sweet Syndrome

Camarillo et al15 described 2 cases of pediatric patients that presented with asymptomatic erythematous and/or violaceous papules, plaques, nodules, and papulovesicles, affecting the extremities, trunk, and face in the setting of SLE or cutaneous LE. Histopathological findings showed an infiltrate of histiocytoid myeloid cells, confirmed by immunostaining (CD68 and myeloperoxidase), accompanying neutrophils, nuclear dust, and leukocytoclastic debris. Camarillo et al coined these lesions “nonbullous histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatitis.” “Nonbullous histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatitis” is distinct from histiocytoid Sweet syndrome because it is associated with AICTDs but not with malignant neoplasms,80 fever and general symptoms are absent,15 and a more abundant neutrophil infiltrate is present.15

Neutrophilic Urticarial Dermatosis and LE

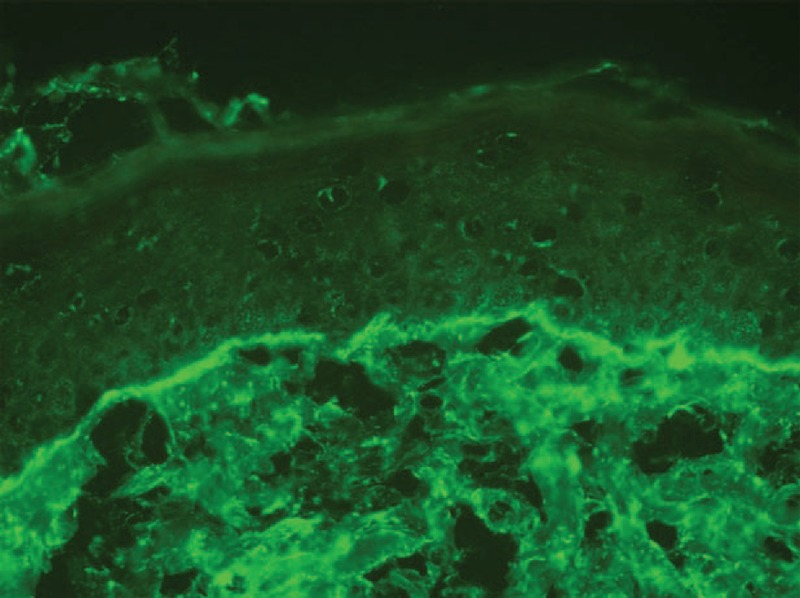

Kieffer et al14 proposed neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis as a distinct entity from the neutrophilic variant of common urticaria. Neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis is characterized by an urticarial eruption: pale, flat or only slightly raised, nonpruritic macules, papules, or plaques, which disappear within hours without leaving any sequelae. Neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis has a different histological pattern than urticaria and a significant interstitial distribution of the neutrophilic infiltrate; the distribution is along the collagen bundles and in the deep part of the reticular dermis, with significant leukocytoclasia. There is usually moderate or no edema, and it is usually diffuse in neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis. Eosinophils and mononuclear cells are absent or scarce. Kieffer et al reviewed the literature on neutrophilic urticarial and identified 50 probable cases of neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis; they reported a series of 9 patients with neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis. Seven of the 9 patients, and the majority of cases of the literature, had systemic involvement, which included autoinflammatory diseases associated with NLRP3 mutations (n = 22), Schnitzler syndrome (n = 17), adult-onset Still disease (n = 5), and LE (n = 3). Schnitzler syndrome and adult-onset Still disease are multifactorial diseases that most likely involve autoinflammatory pathways. Kieffer et al speculated that many of the diseases associated with neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis are related to a disorder of the innate immunity, which eventually results in autoinflammation. In our study, cases 3, 4, and 5 had clinical and histopathological features of neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis. In contrast to the cases of neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis associated with SLE reported by Kieffer et al, which had a known diagnosis of SLE, our 3 cases occurred within the early and nonestablished stages of SLE (case 3 and 5) or cutaneous LE (case 4) (Table 1, Figures 5 and 6A and B). Direct immunofluorescence performed on the skin biopsy of case 2 showed a lupus band within the neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis aspect (Figure 7). Our cases of neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis associated with cutaneous LE may support the hypothesis that pathogenesis of early cutaneous lesions of LE may involve the innate immune system.81

FIGURE 5.

Neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis on white striae in the context systemic LE (case 3). LE = lupus erythematosus.

FIGURE 6.

(A) Interstitial diffuse infiltrate of neutrophils associated with leukocytoclastic debris, without vasculitis suggestive of neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis (case 3) (hematoxylin–eosin stain; original magnifications, 40). (B) Intradermal diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate (case 3) (hematoxylin–eosin stain; original magnifications, 200).

FIGURE 7.

Immunofluorescence showed granular deposition of IgG at the dermal–epidermal junction (case 5).

Palisaded Neutrophilic Granulomatous Dermatitis and AICTD

Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis is a rare cutaneous manifestation, which is most commonly reported with rheumatoid arthritis;82 however, it has also been associated with SLE (n = 12),16,83–89 inflammatory bowel disease, lymphoproliferative disorders, and systemic sclerosis.90 The clinical manifestations of palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis include asymptomatic or intensely painful papules, nodules, linear subcutaneous indurated cordlike bands, and plaques on multiple body sites. The histological examination typically shows a dense neutrophilic infiltrate with degenerated collagen, leukocytoclastic debris, and palisading granulomas, without vasculitis. It has been proposed that the histological appearances of palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis vary from early (dense inflammatory infiltrates, composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils) to late stages (palisading granulomas with fibrosis) of the disease.83,84

Bullous LE

Bullous LE typically affects young adults. Clinical manifestations include vesicles and bullae of acute onset, which arise from sun-exposed sites but may also be widespread. Histological findings show subepidermal vesicles-containing neutrophils with microabscesses, nuclear ‘dust,’ and fibrin at the tips of dermal papillae. Direct immunofluorescence shows linear deposition of IgA, IgG, and IgM and, to a lesser extent, C3 at the basement membrane. Indirect immunofluorescence may show antitype VII collagen antibodies (Abs), which are the same Abs found in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.91 Approximately, 70 cases of bullous LE have been reported in the literature.17 Our case of bullous LE (case 6, Table 1 and Figure 8) displayed a particularly abundant neutrophilic skin infiltrate. As in our case, glomerulonephritis, hypocomplementemia, and antidouble-stranded DNA (dsDNA) Abs are common. Despite its neutrophilic infiltrate, classifying bullous LE as a “neutrophilic cutaneous LE”22 or a “ND associated with SLE” should be questioned, as bullous LE shares many clinical, histological, and immunological features with epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Furthermore, typically acquired autoAbs-mediated blistering diseases can coexist with SLE (eg, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita,92,93 bullous pemphigoid,94 pemphigus,95 dermatitis herpetiformis,96 and linear IgA bullous dermatosis97).

FIGURE 8.

Bullous LE on sun-exposed areas (case 6). LE = lupus erythematosus.

Amicrobial Pustulosis of the Folds and SLE

Amicrobial pustulosis of the folds has been considered to belong to the spectrum of noninfectious NDs associated with autoimmune disorders. Amicrobial pustulosis of the folds presents as small pustules that predominantly affect the face, scalp, and flexures;19 it may involve extracutaneous localizations, such as colonic neutrophilic ulcerations.98 Histopathological examination demonstrates subcorneal multilocular pustules, associated with a superficial perivascular and interstitial neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate. Amicrobial pustulosis of the folds has been primarily described in association with SLE (n = 15), LE (n = 3), Sharp syndrome (n = 2), mixed CTDs (n = 1), Sjögren syndrome (n = 1), rheumatoid arthritis (n = 1), and organ-specific autoimmune diseases, such as autoimmune hepatitis,99 celiac disease, myasthenia gravis, and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.100 In their case reports and reviews in 2007, Marzano et al101 showed that there were various autoAbs found in the context of amicrobial pustulosis of folds (antinuclear 76%; anti-dsDNA 24%; anti-Ro/SSA 19%; anti-ribonucleoprotein 14%; antismooth-muscle 10%; others ≤5%). Skin flares of amicrobial pustulosis of folds were not associated with systemic autoimmune disease flares. Lee et al102 reported the only case of amicrobial pustulosis of folds occurring in the context of Crohn disease, which is considered as a polygenic autoinflammatory syndrome. The pustular lesions, which were essentially located on the scalp of a 22-year-old woman, occurred under long-term therapy with infliximab; this may be considered as a cutaneous complication of antitumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) treatment. Moreover, interface dermatitis on histological examination was suggestive of induced cutaneous LE.102

Autoimmunity-Related ND

Saeb-Lima et al20 used the term autoimmunity-related ND to describe an entity of specific AICTD lesions (urticarial or erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques or nodules, with histological features of interstitial and perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate with leukocytoclasia, vacuolar alteration along the dermal–epidermal junction, and no vasculitis) with unusual neutrophilic infiltrate, which were frequently, but not exclusively, encountered in the setting of SLE (also encountered in association with rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren syndrome).20 In 2006, Gleason et al21 used the term “Nonbullous neutrophilic lupus erythematosus” to describe the same entity exclusively encountered in the setting of SLE; this was followed by the description by Brinster et al103 in 2012.

Autoimmunity-Related ND and LE

We described 1 case (case 7, Table 1 and Figure 9) of cutaneous lesions of LE with classical histological features of LE, that is, vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer of the epidermis, a patchy dermal lymphocytic infiltrate (interface dermatitis) associated with an unusual neutrophilic infiltrate. We found 20 cases in the literature, with similar histological features.13,20,21,79,103,104 The clinical presentation of skin lesions was either “classical” LE (erythematous annular or discoid macules or plaques, n = 9)79,104 or “non-classical” LE (erythematous macules, urticarial papules, or plaques, n = 11).13,20,21,103

FIGURE 9.

Autoimmunity-related ND in the context of cutaneous LE tumidus (case 7). LE = lupus erythematosus, ND = neutrophilic dermatosis.

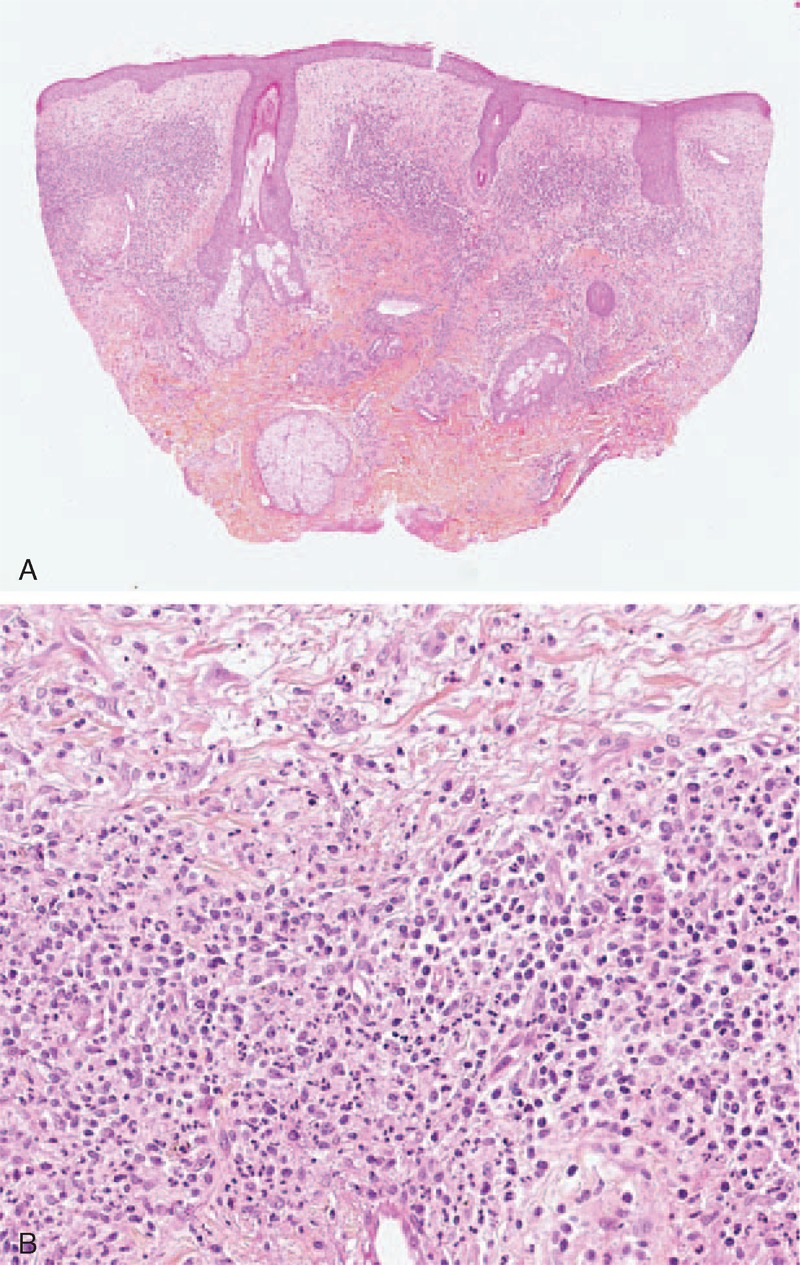

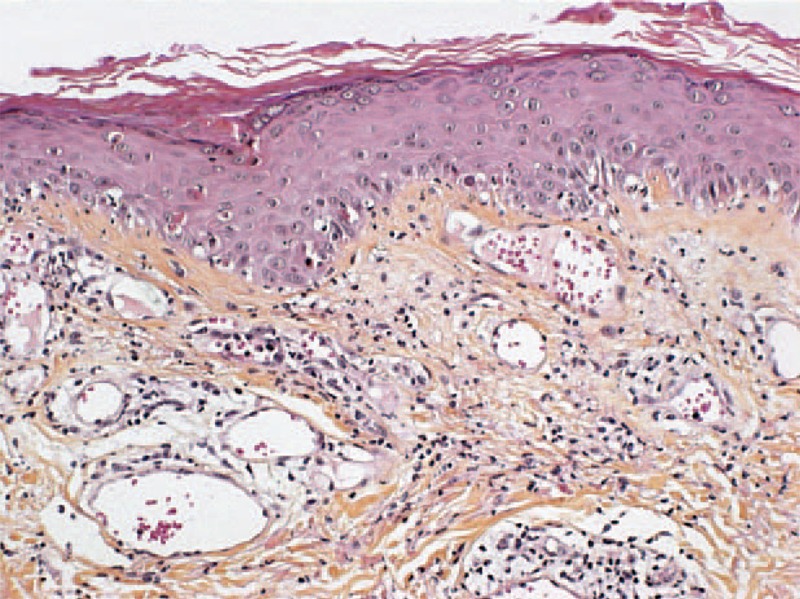

Autoimmunity-Related ND and DM

We described 1 DM patient (case 8, Table 1) in whom a skin biopsy showed histological classical features of DM, that is, interface dermatitis and edema but with a significant neutrophilic infiltrate (Figure 10). Generally, DM skin infiltrate is rare and mainly includes CD4+ T lymphocytes, some macrophages, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils.26 Ito et al105 reported a case of specific DM skin lesions on the back of the hands, face, and trunk; a skin biopsy showed a diffuse infiltration of neutrophils through the dermis, with a few lymphocytes. Caproni et al106 studied the immunophenotype of cells infiltrating the skin pathognomonic lesions (Gottron papules or Gottron sign) of 8 patients with DM. They showed that the main infiltrating cells were activated CD4+ T cells. The large quantity of myeloperoxidase-positive cells led to the conclusion that neutrophil granulocytes were the second most abundant population; these cells infiltrated the perivascular upper dermis and, oftentimes, the epidermis.

FIGURE 10.

Interface dermatitis associated with slight infiltrate composed primarily with neutrophils and few lymphocytes, suggestive of autoimmunity-related ND (case 8) (hematoxylin–eosin stain; original magnifications, 200). ND = neutrophilic dermatosis.

Neutrophilic Annular Erythema and Sjögren Syndrome

Clinical characteristics of annular erythema include an elevated erythematous border and central pallor, suggestive of Sweet syndrome; a red scaly polycyclic lesion, suggestive of subacute LE; or a papulous annular erythema,107 without a subsequent scar or pigmentation.108 Histological features of annular erythema include a deep perivascular and/or periappendageal polymorphic infiltrate, primarily composed of lymphocytes, which may be associated with neutrophils and plasma cells.108 First described in a Japanese series of 22 cases in 1989,108 the association of annular erythema and Sjögren syndrome has mostly been reported in the Asian population; annular erythema is more often associated with cutaneous LE in the occidental population.109 Although most published cases show mixed lymphocytic infiltrate with some neutrophils,107 there have been few reported cases of neutrophilic infiltrate histologically.110–116 We report the first case of annular erythema of the face with significant neutrophilic infiltrate, associated with AICTD (case 9, Table 1 and Figure 11). We chose to designate this case with the term “neutrophilic annular erythema” because clinical and histological signs were suggestive of Sjögren annular erythema; however, there was an unusual neutrophilic infiltrate. Notably, this case (case 9) is interesting because it describes the second117 reported association between necrotizing autoimmune myopathy and Sjögren syndrome. Necrotizing autoimmune myopathy is distinct from other inflammatory myopathies due to muscle necrosis and regeneration without inflammatory infiltrate on muscle biopsy; in addition, there is positivity of the antisignal recognition particle Abs.118

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Mechanism of Neutrophilic Infiltrate in AICTD Skin Lesions

Marzano et al studied the cytokine expression in skin lesions of pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome as compared with healthy skin.119 They showed that IL-1β and its receptors, IL-8 and IL-17, TNFα, the chemokines CXCL1/2/3 and CXCL16, and metalloproteinases 2 and 9 (MMP-2, MMP-9) were significantly overexpressed in skin lesions when compared with normal skin. All of these overexpressed cytokines amplify the inflammatory response and neutrophil recruitment. The pathogenesis of pyoderma gangrenosum in inflammatory bowel disease has also been proposed to be an abnormal immune response consisting of cross-reacting Abs directed towards common antigens in the bowel and skin.120 The neutrophilic infiltrate in AICTDs may also be explained by the activation of the innate immune system because of immune complex deposition and complement cascade activation; it may also be due to a global aberrant innate immune response to environmental triggers. The adaptive immune system may also be involved in the neutrophilic infiltration, particularly through the T helper lymphocytes (Th) 17-cell subset. Th17 cells secrete neutrophil-recruiting chemokines, such as IL-17A and G-CSF. Local synthesis of IL-17A by infiltrating Th17 cells in skin lesions of AICTDs could explain the presence of a nonspecific neutrophilic infiltrate in specific skin lesion of AICTDs, which are classified as autoimmunity-related ND. Neutrophils may also be overrecruited in AICTD skin lesions because of an abnormal expression and/or activation of adhesion/migration molecules through the endothelial barrier of inflamed tissues.121 Caproni et al106 proposed that the neutrophilic infiltrate described in specific skin lesions of DM could be explained by increased expression of adhesion molecules, such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and E-selectins on endothelial cells.

Pathogenic Role of the Neutrophilic Infiltrate in AICTD Skin Lesions

Aberrant and/or excessive neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation (NETosis) is increasingly believed to play an important role in the development and perpetuation of autoimmune diseases. NETs describe nuclear chromatin fibers actively extruded from the neutrophil in response to stimulating signals (lipopolysaccharide, IL-8, TNFα, bacteria, fungi, and parasites).122 NETs bind histones, IL-17, and antimicrobial components to kill invading microbes. In peripheral blood of SLE patients, an abnormal neutrophil subset (the low density granulocytes) has an increased capacity to synthesize NETs. Affected skin and kidneys from LE patients are infiltrated by these netting neutrophils.123 In addition, sera from patients with active SLE have a reduced ability to degrade in vitro generated NETs.124,125 Antimicrobial components exposed by NET drive an immunostimulatory signal, which facilitates the uptake and recognition of self-dsDNA, histones, and IFNα synthesis by plasmacytoid dendritic cells.122,123 This process could induce the activation of autoimmune T and B lymphocytes. Activated autoreactive lymphocytes induce DNA-containing immune complexes and lead to IL-17 production; this may trigger neutrophil activation and NET formation,121 leading to a vicious cycle.

THERAPEUTIC

The treatment strategies of NDs consist of modulating the neutrophilic activation, maturation, or migration. Oral corticosteroid use is efficient and has been proven be effective. Sulphones (dapsone), colchicine, potassium iodide, retinoid (acitretin), clofazimine, sulfasalazine, and thalidomide may also be beneficial. Severe corticosteroid-unresponsive cases may be treated with immunosuppressant agents, such as cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, intravenous tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil. Recently, TNFα inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept) have shown good efficacy in pyoderma gangrenosum, especially when pyoderma gangrenosum was associated with inflammatory bowel diseases; this therapy concurrently cured both disease processes.126 In our study, 2 cases (cases 2 and 5) were improved by neutrophil targeting therapy, that is, dapsone; underlying AICTD therapies, that is, prednisolone, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclophosphamide, were effective on neutrophilic skin lesions in the remaining 7 cases, suggesting a parallelism between the 2 disorders.

CONCLUSION

NDs in the setting of AICTDs include many entities in which autoimmune and autoinflammatory pathways are more or less interconnected, which may explain the polymorphic clinical spectrum of the neutrophilic skin symptoms. This review supports the idea that AICTD neutrophilic skin lesions are a distinct entity within the spectrum of cutaneous signs in AICTDs, as has been previously reported.22 Further investigations are needed to clarify the probable part of the neutrophil and innate immunity in the pathogenesis and prognosis of AICTDs; this may lead to new therapeutic targets.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: Abs = antibodies, ACR = American College of Rheumatology, AICTD = autoimmune connective tissue disease, CTD = connective tissue disease, DM = dermatomyositis, dsDNA = double-stranded DNA, IL = interleukin, LE = lupus erythematosus, ND = neutrophilic dermatosis, NET = neutrophil extracellular trap, SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus, Th = T helper lymphocyte, TNFα = tumor necrosis factor α.

MR and JDB have equally contributed to the study and share last author seniorship.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marzano AV, Ishak RS, Saibeni S, et al. Autoinflammatory skin disorders in inflammatory bowel diseases, pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet's syndrome: a comprehensive review and disease classification criteria. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2013; 45:202–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prat L, Bouaziz JD, Wallach D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses as systemic diseases. Clin Dermatol 2014; 32:376–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masters SL, Simon A, Aksentijevich I, et al. Horror autoinflammaticus: the molecular pathophysiology of autoinflammatory disease. Annu Rev Immunol 2009; 27:621–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffman HM, Mueller JL, Broide DH, et al. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle–Wells syndrome. Nat Genet 2001; 29:301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MeSH database [database online]. Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuhn A, Landmann A. The classification and diagnosis of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun 2014; 48–49:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilliam JN, Sontheimer RD. Distinctive cutaneous subsets in the spectrum of lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1981; 4:471–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw PJ, McDermott MF, Kanneganti TD. Inflammasomes and autoimmunity. Trends Mol Med 2011; 17:57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masatlioğlu SP, Göktay F, Mansur AT, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting as pyoderma gangrenosum in two cases. Rheumatol Int 2009; 29:837–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuji H, Yoshifuji H, Nakashima R, et al. Sweet's syndrome associated with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report and review of the literature. J Dermatol 2013; 40:641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Concheiro J, León A, Pardavila R, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands in rheumatoid arthritis. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2010; 101:280–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoo WH, Moon SK, Park TS, et al. A case of Sweet's syndrome in patient with dermatomyositis. Korean J Intern Med 1999; 14:78–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pavlidakey P, Mills O, Bradley S, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis revisited: an initial presentation of lupus? J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 67:e29–e35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kieffer C, Cribier B, Lipsker D. Neutrophilic urticarial dermatosis a variant of neutrophilic urticaria strongly associated with systemic disease. Report of 9 new cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2009; 88:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Camarillo D, McCalmont TH, Frieden IJ, et al. Two pediatric cases of nonbullous histiocytoid neutrophilic dermatitis presenting as a cutaneous manifestation of lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol 2008; 144:1495–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Germanas JP, Mehrabi D, Carder KR. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis in a 12-year-old girl with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:S60–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vassileva S. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol 2004; 22:129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durani B, Andrassy K, Hartschuh W. Neutrophilic dermatosis with an erythema gyratum repens-like pattern in systemic lupus erythematosus. Acta Derm Venereol 2005; 85:455–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crickx B, Diego ML, Guillevin L. Pustulose amicrobienne et lupus érythémateux systémique March 1991, Communication No. 11 (letter). Journées Dermatologiques de Paris. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saeb-Lima M, Charli-Joseph Y, Rodríguez-Acosta ED, et al. Autoimmunity-related neutrophilic dermatosis: a newly described entity that is not exclusive of systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Dermatopathol 2013; 35:655–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gleason BC, Zembowicz A, Granter SR. Non-bullous neutrophilic dermatosis: an uncommon dermatologic manifestation in patients with lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol 2006; 33:721–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipsker D. The need to revisit the nosology of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: the current terminology and morphologic classification of cutaneous LE: difficult, incomplete and not always applicable. Lupus 2010; 19:1047–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1997; 40:1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shiboski SC, Shiboski CH, Criswell L, et al. American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for Sjögren's syndrome: a data-driven, expert consensus approach in the Sjögren's International Collaborative Clinical Alliance cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012; 64:475–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. N Engl J Med 1975; 292:344–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al. Rook's, Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed.Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahronowitz I, Harp J, Shinkai K. Etiology and management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol 2012; 13:191–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powell FC, Schroeter AL, Su WP, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of 86 patients. Q J Med 1985; 55:173–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinto GM, Cabeças MA, Riscado M, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with systemic lupus erythematosus: response to pulse steroid therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991; 24:818–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roger D, Aldigier JC, Peyronnet P, et al. Acquired ichthyosis and pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Dermatol 1993; 8:268–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holbrook MR, Doherty M, Powell RJ. Post-traumatic leg ulcer. Ann Rheum Dis 1996; 55:214–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wenzel HC, Wollina U. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting as pyoderma gangrenosum. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1995; 4:20–25. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmid MH, Hary C, Marstaller B, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with the secondary antiphospholipid syndrome. Eur J Dermatol 1998; 8:45–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakamoto T, Hashimoto T, Furukawa F. Pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Dermatol 2002; 12:485–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waldman MA, Callen JP. Pyoderma gangrenosum preceding the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatology 2005; 210:64–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reddy V, Dziadzio M, Hamdulay S, et al. Lupus and leg ulcers—a diagnostic quandary. Clin Rheumatol 2007; 26:1173–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hasselmann DO, Bens G, Tilgen W, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinical presentation and outcome in 18 cases and review of the literature. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2007; 5:560–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hind A, Abdulmonem AG, Al-Mayouf S. Extensive ulcerations due to pyoderma gangrenosum in a child with juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus and C1q deficiency. Ann Saudi Med 2008; 28:466–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kole AK, Ghosh A. Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus in a tertiary referral center. Indian J Dermatol 2009; 54:132–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nuzhatun N, Masood Q, Iffat Shah. Pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with antiphospholipid antibody negative systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report. Iran J Dermatol 2011; 4:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhat RM, Nandakishore B, Sequeira FF, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an Indian perspective. Clin Exp Dermatol 2011; 36:242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ravic-Nikolic A, Milicic V, Ristic G, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Sjögren syndrome. Eur J Dermatol 2009; 19:392–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saracino A, Kelly R, Liew D, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum requiring inpatient management: a report of 26 cases with follow up. Australas J Dermatol 2011; 52:218–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsai YH, Huang CT, Chia CY, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: intractable leg ulcers in Sjögren's syndrome. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2013; 30:486–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shah M, Lewis FM, Harrington CI. Scrotal pyoderma gangrenosum associated with dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol 1996; 21:151–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet's syndrome. Cutis 1986; 37:167–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rochet NM, Chavan RN, Cappel MA, et al. Sweet syndrome: clinical presentation, associations, and response to treatment in 77 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013; 69:557–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaufmann J, Hein G, Graefe T, et al. Rare association of acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome) with rheumatoid arthritis. Z Rheumatol 2001; 60:263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mrabet D, Saadi F, Zaraa I, et al. Sweet's syndrome in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren's syndrome and lymph node tuberculosis. BMJ Case Rep 2011; 2011: bcr0720103137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamauchi PS, Turner L, Lowe NJ, et al. Treatment of recurrent Sweet's syndrome with coexisting rheumatoid arthritis with the tumor necrosis factor antagonist etanercept. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 54:S122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ratzinger G, Burgdorf W, Zelger BG, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathologic study of 31 cases with review of literature. Am J Dermatopathol 2007; 29:125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bianconcini G, Mazzali F, Candini R, et al. Sweet's syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) associated with Sjögren's syndrome. A clinical case. Minerva Med 1991; 82:869–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prystowsky SD, Fye KH, Goette KD, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis associated with Sjögren's syndrome. Arch Dermatol 1978; 114:1234–1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Souissi A, Benmously R, Fenniche S, et al. Sweet's syndrome: a propos of 8 cases. Tunis Med 2007; 85:49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vatan R, Sire S, Constans J, et al. Association of primary Gougerot-Sjögren syndrome and Sweet syndrome. Apropos of a case. Rev Med Interne 1997; 18:734–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Osawa H, Yamabe H, Seino S, et al. A case of Sjögren's syndrome associated with Sweet's syndrome. Clin Rheumatol 1997; 16:101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Foster EN, Nguyen KK, Sheikh RA, et al. Crohn's disease associated with Sweet's syndrome and Sjögren's syndrome treated with infliximab. Clin Dev Immunol 2005; 12:145–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Neoh CY, Tan AW, Ng SK. Sweet's syndrome: a spectrum of unusual clinical presentations and associations. Br J Dermatol 2007; 156:480–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Makino Y, Ueda S, Ogawa M, et al. A case of Sweet's syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) associated with mixed connective tissue disease. Ryumachi 1992; 32:340–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sequeira W, Polisky RB, Alrenga DP. Neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet's syndrome). Association with a hydralazine-induced lupus syndrome. Am J Med 1986; 81:558–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Servitje O, Ribera M, Juanola X, et al. Acute neutrophilic dermatosis associated with hydralazine-induced lupus. Arch Dermatol 1987; 123:1435–1436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramsey-Goldman R, Franz T, Solano FX, et al. Hydralazine induced lupus and Sweet's syndrome. Report and review of the literature. J Rheumatol 1990; 17:682–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cartee TV, Chen SC. Sweet syndrome associated with hydralazine induced lupus erythematosus. Cutis 2012; 89:121–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Choi JW, Chung KY. Sweet's syndrome with systemic lupus erythematosus and herpes zoster. Br J Dermatol 1999; 140:1174–1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gollol-Raju N, Bravin M, Crittenden D. Sweet's syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2009; 18:377–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goette DK. Sweet's syndrome in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol 1985; 121:789–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Levenstein MM, Fisher BK, Fisher LL, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and Sweet syndrome. A marker of Sjögren syndrome? Int J Dermatol 1991; 30:640–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Katayama I. Subacute lupus erythematosus and Sweet syndrome. Int J Dermatol 1992; 31:165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hou TY, Chang DM, Gao HW, et al. Sweet's syndrome as an initial presentation in systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report and review of the literature. Lupus 2005; 14:399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burnham JM, Cron RQ. Sweet syndrome as an initial presentation in a child with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2005; 14:974–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Satter EK, High WA. Non-bullous neutrophilic dermatosis within neonatal lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol 2007; 34:958–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fernandes NF, Castelo-Soccio L, Kim EJ, et al. Sweet syndrome associated with new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in a 25-year-old man. Arch Dermatol 2009; 145:608–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barr KL, O’Connell F, Wesson S, et al. Nonbullous neutrophilic dermatosis: Sweet's syndrome, neonatal lupus erythematosus, or both? Mod Rheumatol 2009; 19:212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abbas O, Kibbi AG, Rubeiz N. Sweet's syndrome: retrospective study of clinical and histologic features of 44 cases from a tertiary care center. Int J Dermatol 2010; 49:1244–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rochael MC, Pantaleão L, Vilar EA, et al. Sweet's syndrome: study of 73 cases, emphasizing histopathological findings. An Bras Dermatol 2011; 86:702–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tabache F, Kartouti AE, Abdelilah T, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus revealed by sweet syndrome. Joint Bone Spine 2011; 78:420–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barton JL, Pincus L, Yazdany J, et al. Association of sweet's syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus. Case Rep Rheumatol 2011; 2011:242681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Díaz-Corpas T, Mateu-Puchades A, Morales-Suárez-Varela MM, et al. Retrospective study of patients diagnosed with Sweet syndrome in the health area of a tertiary hospital in the autonomous community of Valencia. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2012; 103:233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Larson AR, Granter SR. Systemic lupus erythematosus-associated neutrophilic dermatosis—an underrecognized neutrophilic dermatosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum Pathol 2014; 45:598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Requena L, Kutzner H, Palmedo G, et al. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome: a dermal infiltration of immature neutrophilic granulocytes. Arch Dermatol 2005; 141:834–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lipsker D, Saurat JH. Neutrophilic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. At the edge between innate and acquired immunity? Dermatology 2008; 216:283–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sangueza OP, Caudell MD, Mengesha YM, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis in rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 47:251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol 1994; 130:1278–1283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gulati A, Paige D, Yaqoob M, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with the burning rope sign. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 61:711–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Blaise S, Salameire D, Carpentier PH. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a misdiagnosed cutaneous form of systemic lupus erythematosus? Clin Exp Dermatol 2008; 33:712–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brecher A. Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis. Dermatol Online J 2003; 9:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Misago N, Inoue H, Inoue T, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis in systemic lupus erythematosus with a butterfly rash-like lesion. Eur J Dermatol 2010; 20:128–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Misago N, Narisawa Y, Tada Y, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis caused by cellulitis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Dermatol 2011; 50:1583–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Obermoser G, Zelger B, Zangerle R, et al. Extravascular necrotizing palisaded granulomas as the presenting skin sign of systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol 2002; 147:371–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hantash BM, Chiang D, Kohler S, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis associated with limited systemic sclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 58:661–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gammon WR. Autoimmunity to collagen VII: autoantibody-mediated pathomechanisms regulate clinical-pathological phenotypes of acquired epidermolysis bullosa and bullous SLE. J Cutan Pathol 1993; 20:109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dotson AD, Raimer SS, Pursley TV, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus occurring in a patient with epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Arch Dermatol 1981; 117:422–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McHenry PM, Dagg JH, Tidman JH, et al. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita occurring in association with bullous lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Dermatol 1991; 1993:378–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Clayton CA, Burnham TK. Systemic lupus erythematosus and coexisting bullous pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol 1982; 7:236–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hidalgo-Tenorio C, Sabio-Sanchez JM, Tercedor-Sanchez J, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris and systemic lupus erythematosus in a 46-year-old man. Lupus 2001; 10:824–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Thomas IJR, Su DWP. Concurrence of lupus erythematosus and dermatitis herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol 1983; 119:740–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lau M, Kaufmann-Grunzinger I, Raghunath MA. Case report of a patient with features of systemic lupus erythematosus and linear IgA disease. Br J Dermatol 1991; 124:498–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kerl K, Masouyé I, Lesavre P, et al. A case of amicrobial pustulosis of the folds associated with neutrophilic gastrointestinal involvement with systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatology 2005; 211:356–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Méndez-Flores S, Charli-Joseph Y, Saeb-Lima M, et al. Amicrobial pustulosis of the folds associated with autoimmune disorders: systemic lupus erythematosus case series and first report on the association with autoimmune hepatitis. Dermatology 2013; 226:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Boms S, Gambichler T. Review of literature on amicrobial pustulosis of the folds associated with autoimmune disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol 2006; 7:369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Marzano AV, Ramoni S, Caputo R. Amicrobial pustulosis of the folds: report of 6 cases and a literature review. Dermatology 2008; 216:305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee HY, Pelivani N, Beltraminelli H, et al. Amicrobial pustulosis-like rash in a patient with Crohn's disease under anti-TNF-alpha blocker. Dermatology 2011; 222:304–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Brinster NK, Nunley J, Pariser R, et al. Nonbullous neutrophilic lupus erythematosus: a newly recognized variant of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 66:92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kanekura T, Hashiguchi T, Mera Y, et al. Improvement of SLE skin rash with granulocyte and monocyte adsorption apheresis. Dermatology 2004; 208:79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ito A, Funasaka Y, Shimoura A, et al. Dermatomyositis associated with diffuse dermal neutrophilia. Int J Dermatol 1995; 34:797–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Caproni M, Torchia D, Cardinali C, et al. Infiltrating cells, related cytokines and chemokine receptors in lesional skin of patients with dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol 2004; 151:784–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Teramoto N, Katayama I, Arai H, et al. Annular erythema: a possible association with primary Sjögren's syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989; 20:596–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Katayama I, Teramoto N, Arai H, et al. Annular erythema. A comparative study of Sjögren syndrome with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Int J Dermatol 1991; 30:635–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lee CW. Clinical constellation of annular erythema associated with anti-Ro/La autoantibodies. J Korean Med Sci 2000; 15:199–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cox NH, McQueen A, Evans TJ, et al. An annular erythema of infancy. Arch Dermatol 1987; 123:510–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Annessi G, Signoretti S, Angelo C, et al. Neutrophilic figurate erythema of infancy. Am J Dermatopathol 1997; 19:403–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Khan Durani B, Andrassy K, Hartschuh W. Neutrophilic dermatosis with an erythema gyratum repens-like pattern in systemic lupus erythematosus. Acta Derm Venereol 2005; 85:455–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Trébol I, González-Pérez R, García-Rio I, et al. Paraneoplastic neutrophilic figurate erythema. Br J Dermatol 2007; 156:396–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ozdemir M, Engin B, Toy H, et al. Neutrophilic figurate erythema. Int J Dermatol 2008; 47:262–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Patrizi A, Savoia F, Varotti E, et al. Neutrophilic figurate erythema of infancy. Pediatr Dermatol 2008; 25:255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Koguchi H, Arita K, Yamane N, et al. Erythema annulare centrifugum-like neutrophilic dermatosis: effects of potassium iodide. Acta Derm Venereol 2012; 92:333–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ponge T, Mussini JM, Ponge A, et al. Primary Gougerot-Sjögren syndrome with necrotizing polymyositis: favorable effect of hydroxychloroquine. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1987; 143:147–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Liang C, Needham M. Necrotizing autoimmune myopathy. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2011; 23:612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Marzano AV, Fanoni D, Antiga E, et al. Expression of cytokines, chemokines and other effector molecules in two prototypic autoinflammatory skin diseases, pyoderma gangrenosum and sweet's syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol 2014; 178:48–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Huang BL, Chandra S, Shih DQ. Skin manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Front Physiol 2012; 3:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Németh T, Mócsai A. The role of neutrophils in autoimmune diseases. Immunol Lett 2012; 143:9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Simon D, Simon HU, Yousefi S. Extracellular DNA traps in allergic, infectious, and autoimmune diseases. Allergy 2013; 68:409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Villanueva E, Yalavarthi S, Berthier CC, et al. Netting neutrophils induce endothelial damage, infiltrate tissues, and expose immunostimulatory molecules in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol 2011; 187:538–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hakkim A, Fürnrohr BG, Amann K, et al. Impairment of neutrophil extracellular trap degradation is associated with lupus nephritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:9813–9818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Leffler J, Martin M, Gullstrand B, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps that are not degraded in systemic lupus erythematosus activate complement exacerbating the disease. J Immunol 2012; 188:3522–3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Chan JL, Graves MS, Cockerell CJ, et al. Rapid improvement of pyoderma gangrenosum after treatment with infliximab. J Drugs Dermatol 2010; 9:702–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]