Abstract

Recent studies indicated that preoperative radiotherapy significantly reduces the lymph nodes (LNs) harvest from patients with rectal cancer. This may weaken the prognostic value of current standard of LNs retrieval (≥12 LNs). This study investigates the prognostic impact of the LN counts on pathologically LN-negative (ypN0) after preoperative radiotherapy for patients with rectal cancer.

Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registered nonmetastatic rectal cancer patients diagnosed between 1998 and 2005 were included in this study. Optimal cutoff value for number of LNs retrieved was determined by X-tile program. Log-rank tests were adopted to compare the rectal cause specific survival (RCSS) for ypN0 patients using separated cutoff value of LN counting from 2 to 20. Correlation between LN count and tumor regression was investigated in an additional 221 patients from Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (FUSCC).

The results showed that there were fewer number of LNs examined in patients with preoperative radiotherapy than those without (8.9 vs 10.9, P < 0.001). X-tile program identified the difference in survival was most significant (maximum of χ2 log-rank values) for the number 4. And 5-year RCSS increased accordingly with the cutoff values ranging from 4 to 15, which were confirmed as optimal cutoff and validated as independent prognostic factors in multivariate regression analysis (χ2 = 50.65, P < 0.001). Patients in FUSCC set were found to have fewer LNs retrieval in group of good tumor regression than in that of poor one (P = 0.01).

These results confirmed the reduced number of LN retrieval in patients with rectal cancer treated with preop-RT. LN count is still an independently prognostic factor for ypN0 rectal cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Rectal cancer is one of the most common malignancies with an estimated 40 000 new cases expected to occur in 2014 in the United States. Combined with colon cancer, colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks as the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States.1 Preoperative radiation (preop-RT) followed by a curative resection has become the standard of care to treat locally advanced rectal cancer because of the oncologic benefit of reduced local recurrence rate.2,3

Studies have demonstrated that the number of retrieved lymph nodes (LNs) is associated significantly with relapse and survival rates in patients with stage II rectal cancer.4–6 To validate appropriate staging, pathological examination of at least 12 LNs in CRC patients has been recommended by the International Union Against Cancer and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) since 2000. However, evidence indicated that preop-RT may decrease the number of analyzable LNs that the surgeons and pathologists are able to retrieve.7–9 The prognostic value of current standard (≥12 LNs retrieval) may be questionable as well under this circumstance.

Given the growing importance of preop-RT in the management for patients with rectal cancer, there existed increasing doubts about the rationale of at least 12 LNs retrieved in ypTNM staging.10 We designed this study to assess the impact of the number of LNs examined on survival of patients with rectal cancer after preop-RT and to find a reasonable LNs cutoff value that allows a reliable staging of ypTNM, we utilized a larger Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registered database and we used X-tile program11 to determine the optimal cutoff. Moreover, as the SEER data lack information on the neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy (NCRT) methods, NCRT response, and the quality of surgery, we further clarified these relevant issues in another set of patients with locally advanced rectal cancer from Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (FUSCC).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Selection in SEER Database

The SEER cancer statistics review (http://seer.cancer.gov/data/citation.html), a review on the most recent cancer incidence, mortality, survival, prevalence, and lifetime risk statistics, is published annually by the Data Analysis and Interpretation Branch of the National Cancer Institute, MD, and USA. The current SEER database consists of 17 population-based cancer registries that represent approximately 28% of the population in the United States. The SEER data contain no identifiers and are publicly available for studies of cancer-based epidemiology and TNM staging of CRC,12,13 gastric cancer,14 esophageal cancer,15 and others.

Cases of invasive rectal cancer (C20.9-Rectum, NOS) diagnosed between 1998 and 2005 were extracted from the SEER database (SEER∗Stat 8.1.2) according to the Site Recode Classifications. Histological type were limited to adenocarcinoma (8150/3, 8210/3, 8261/3, 8263/3), mucinous adenocarcinoma (8480/3), and signet ring cell carcinoma (8490/3). Only patients between 18 and 80 years old and whose rectal cancer was a single primary tumor were included into the current study. Patients diagnosed after 2006 were excluded to ensure an adequate follow-up time. Other exclusion criterions were as follows: pathologically LNs positive, synchronous distance metastases, patients died within 30 days after surgery.

Patient Selection in the FUSCC Set

The FUSCC rectal cancer dataset was built prospectively and recorded the rectal cancer patients treated at FUSCC, Shanghai, China since January, 2006. To validate the findings from the SEER set and to clarify relevant issues mentioned above, we used FUSCC rectal cancer dataset between January 2006 and December 2012. Consecutive patients who were histologically diagnosed to have a single primary tumor of AJCC stages II to III rectal cancer (cT3-T4 and/or cN+), located within 12 cm of the anal verge, and treated with NCRT before a radical surgery were included. All patients were pathologically confirmed to have no LN metastasis after surgery (ypN0). Patients who received only local resection were excluded from this study.

All patients received intensity-modulated radiation therapy to the pelvis of 50 Gy and a concomitant boost of 5 Gy to the primary tumor in 25 fractions, and concurrent with capecitabine (625 mg/m2 bid d1–5 weekly) based chemotherapy. Radical surgery was scheduled 6 to 8 weeks after NCRT. Tumor regression grade (TRG) was adopted to access the treatment effect on primary tumor after NCRT. TRG of the primary tumor was semiquantitatively determined by the amount of viable tumor versus the amount of fibrosis, ranging from no evidence of any treatment effect to a complete response with no viable tumor identified, as described by Dworak et al.16 The following were characteristics of each grade: grade 0, no regression; grade 1, minor regression (dominant tumor mass with obvious fibrosis in 25% or less of the tumor mass); grade 2, moderate regression (dominant tumor mass with obvious fibrosis in 26%–50% of the tumor mass); grade 3, good regression (dominant fibrosis outgrowing the tumor mass; ie, >50% tumor regression); and grade 4, total regression (no viable tumor cells, only fibrotic mass).17

Informed Consent and Institutional Review Board Approval

This study was partly based on a publicly available data (the SEER database) and we have got the permission to access them on purpose of research only (Reference number: 12768-Nov2012). It did not include interaction with humans or use personal identifying information. Thus, the informed consent for this part was not required. All patients from FUSCC dataset have provided written informed consent. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the FUSCC.

Statistical Analyses

Age, sex, race, extension of primary tumor invasion, total number of LNs examined, histological grade, survival time, and rectal cancer cause specific survival (RCSS) were extracted from SEER database and FUSCC set separately. All cases were restaged according to the criteria described in the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (7th edition, 2010). The primary endpoint of this study was RCSS, which was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of cancer-specific death. Deaths attributed to the rectal cancer of interest are treated as events and deaths from other causes are treated as censored observation.

The LNs cutoff points were produced and analyzed using the X-tile program (http://www.tissuearray.org/rimmlab/), which identified the cutoff with the minimum P values from log-rank χ2 statistics for the categorical LNs in terms of survival.11 Survival curves were generated using Kaplan–Meier estimates, differences between the curves were analyzed by log-rank test. Cox regression models were built for analysis of risk factors for survival outcomes in preop-RT rectal cancer patients. Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package SPSS for Windows, version 17 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). A two-tailed P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics in SEER Database

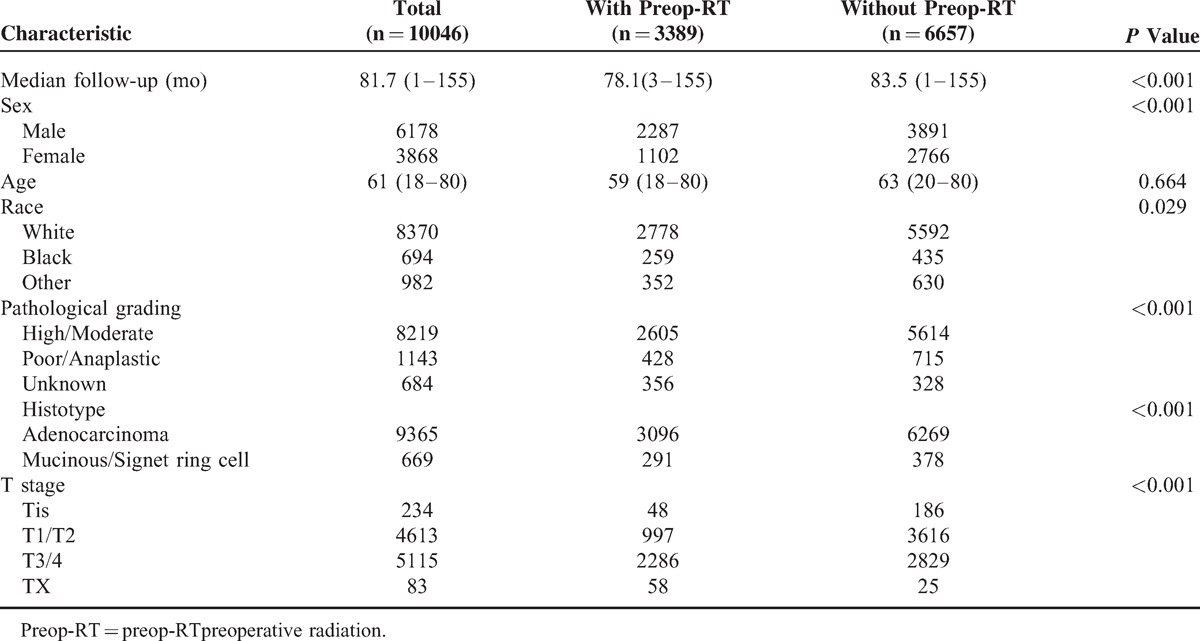

We identified 10 046 eligible patients who had pathologically negative LNs on assessment during the 8-year study period in SEER database, including 3389 patients in group with preop-RT (ypN0 group) and 6657 in group of surgery without preop-RT (pN0 group). The median ages of ypN0 group and pN0 group were 59 (18–80) and 62 (20–80) years old, respectively, which have no significant difference (P = 0.66). Majority were the White in race in both groups. Compared with patients in pN0 group, patients in ypN0 group had higher proportion of males, more common of poor/anaplastic in pathological grading, more prevalence of adenocarcinoma in histological type, and more ypT3/4 in tumor stage, (P < 0.001, for all). Patient demographics and pathological features are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Clinicopathologic Features of Rectal Cancer With and Without Preop-RT in Pathologically Lymph Node-Negative Patients

Comparison of LNs Status of Patients With and Without Preop-RT in SEER Database

The mean number of LNs examined in ypN0 and pN0 group was 8.9 (1–53) and 10.9 (1–86), respectively, which had statistical difference (P < 0.001). In total, 27.15% of patients in ypN0 group and 37.18% in pN0 one, respectively, had been retrieved >12 LNs (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of Lymph Node Status Between With and Without Preop-RT

Identification of Cutoff Points of Minimum Number of LNs Retrieved in SEER Database

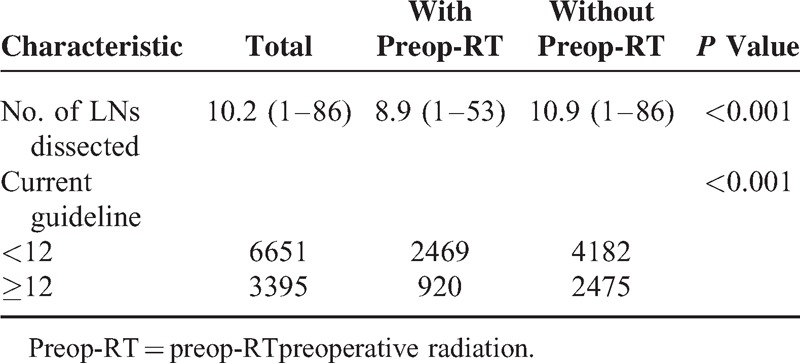

X-tile plots were constructed and the maximum of χ2 log-rank values of 35.72 was achieved when applying 4 as the cutoff value of LN numbers retrieved. This value can be used to divide the cohort into 2 subsets in terms of 5 years (survival rate were 75.9% and 84.5% for patients with <4 and ≥4 LNs retrieval, respectively, P < 0.001) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

X-tile analysis of survival data from the SEER registry. X-tile analysis was done on patient data from the SEER registry, equally divided into training and validation sets. X-tile plots of training sets are shown in the left panels, with plots of matched validation sets shown in the smaller inset. The optimal cut-point highlighted by the black circle in the left panels is shown on a histogram of the entire cohort (middle panels), and a Kaplan-Meier plot (right panels). P values were determined by using the cut-point defined in the training set and applying it to the validation set. Figures 1 shows ypN0 patients optimal cutoff point (4, χ2 = 35.62, P < 0.001).

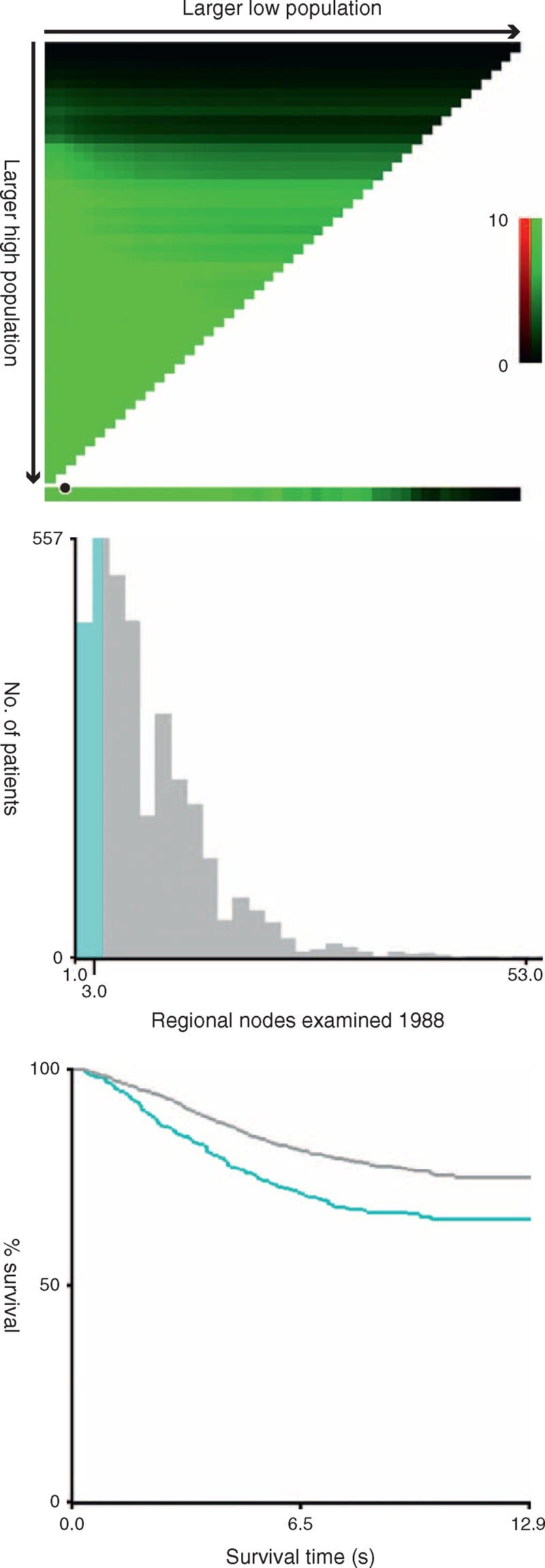

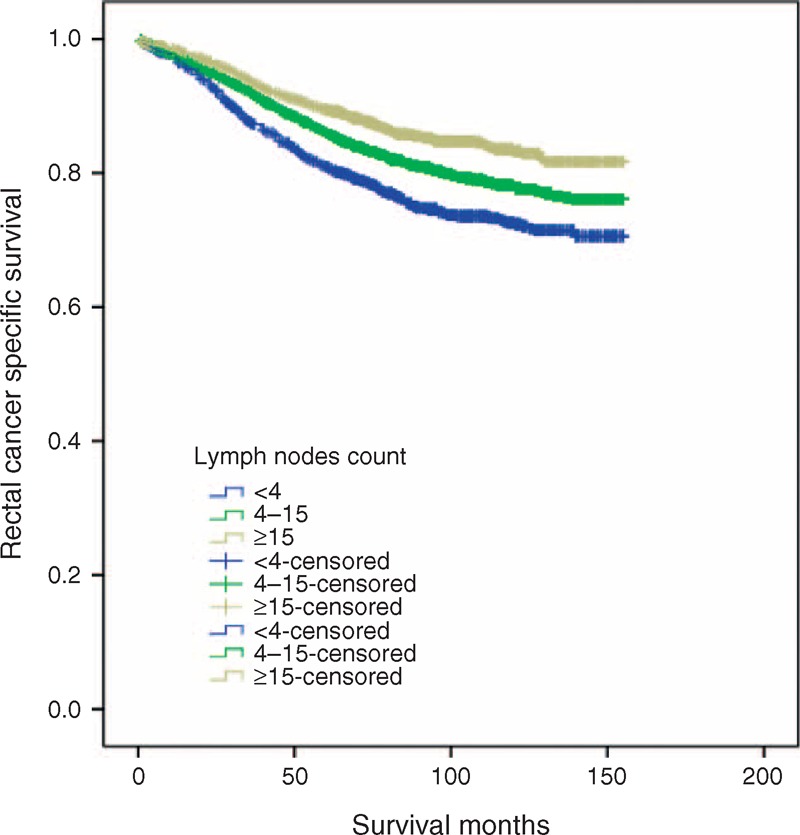

To assess the influence of different LN counts retrieved on ypN0 patients’ 5-year RCSS, we stepped further to analyze the individual result using different cutoff values of LN numbers ranging from 2 to 20. The 5-year RCSS of patients with N (cutoff point) or more nodes and less than N were calculated, respectively. The survival rates of patients with N or more nodes increased gradually when N ranged from 2 to 14. After the number 15, however, the survival rates were roughly the same and the difference between the compared groups were not so significant any more (81.3% vs 89.6%, χ2 = 26.41) (Table 4). Thus, cutoff value of 4 and 15 can be used to divide patients into 3 risk group: high (<4), middle (4–15), and low (≥15) risk subgroup. Significantly, for ypN0 patients, there was an absolute 13.7% improvement in 5-year RCSS if ≥15 LNs were analyzed than those patients of <4 (89.6% vs 75.9%, P < 0.001) (Table 4) (Figure 2).

TABLE 4.

Univariate Analysis for the Influence of Difference Cutoff on RCSS in ypN0 Rectal Cancer Patients

FIGURE 2.

Survival curves in ypN0 rectal cancer patients according to 4 and 15 lymph nodes cutoff, χ2 = 50.65, P < 0.001.

Prognostic Value of Number of LNs Retrieved in SEER Database

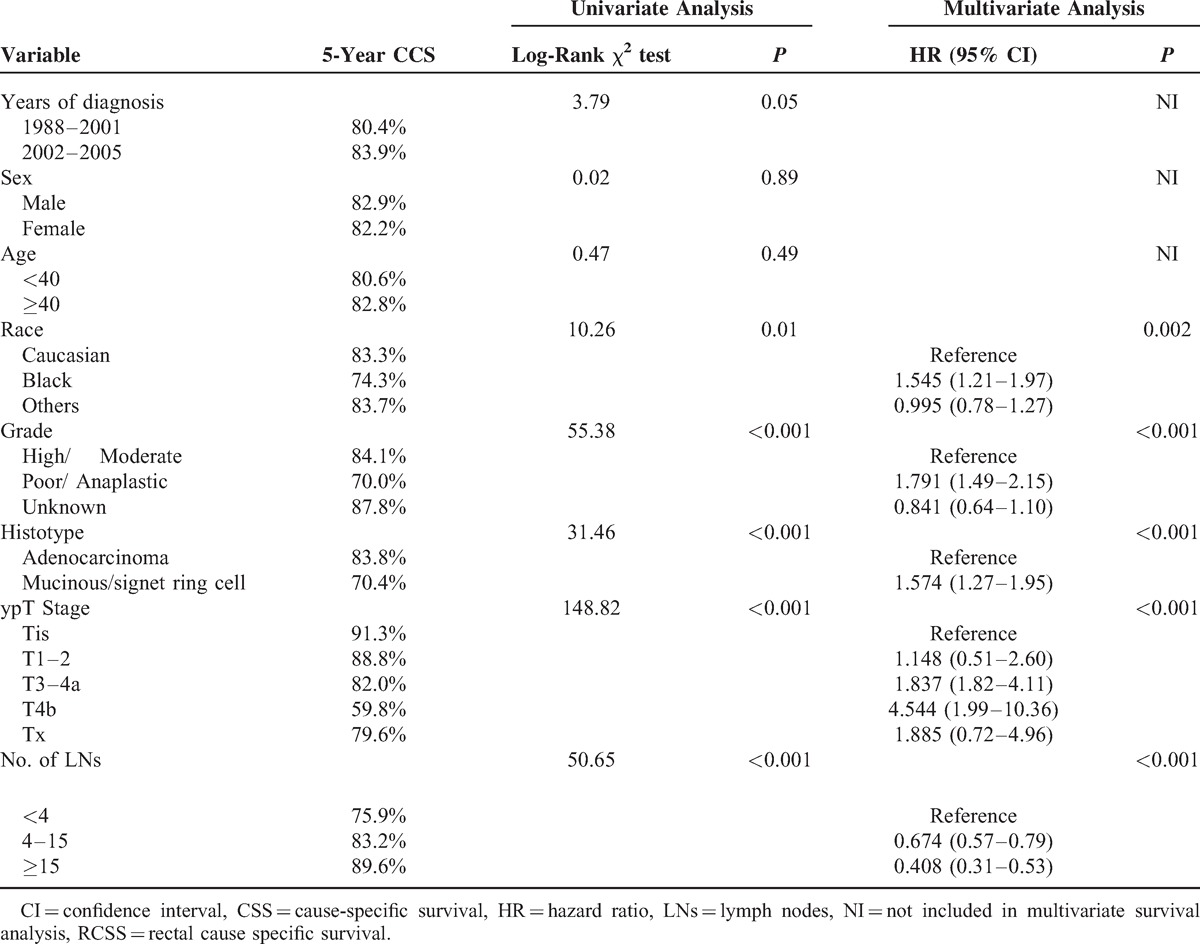

Using Kaplan–Meier estimates, beside of the number of LNs mentioned above, some other clinicopathological factors, including race (P = 0.00), pathological grade (P < 0.001), tumor histotype (P < 0.001), and ypT stage (P < 0.001) were also found to be risk factors for RCSS on univariate analysis. Further multivariate analysis showed the number of LNs retrieved was an independent prognostic factor in ypN0 patients. (LNs: 4–15, hazard ratio (HR): 0.67, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.57–0.79; LNs > 15, HR: 0.41, 95%CI: 0.31–0.53, LNs <4 as reference. P < 0.001) (Table 5)

TABLE 5.

Univariate and Multivariate Survival Analyses for Evaluating the Number of LNs Retrieved Influencing RCSS in ypN0 Rectal Cancer

Evaluating the SEER Database Outcomes in the FUSCC Set

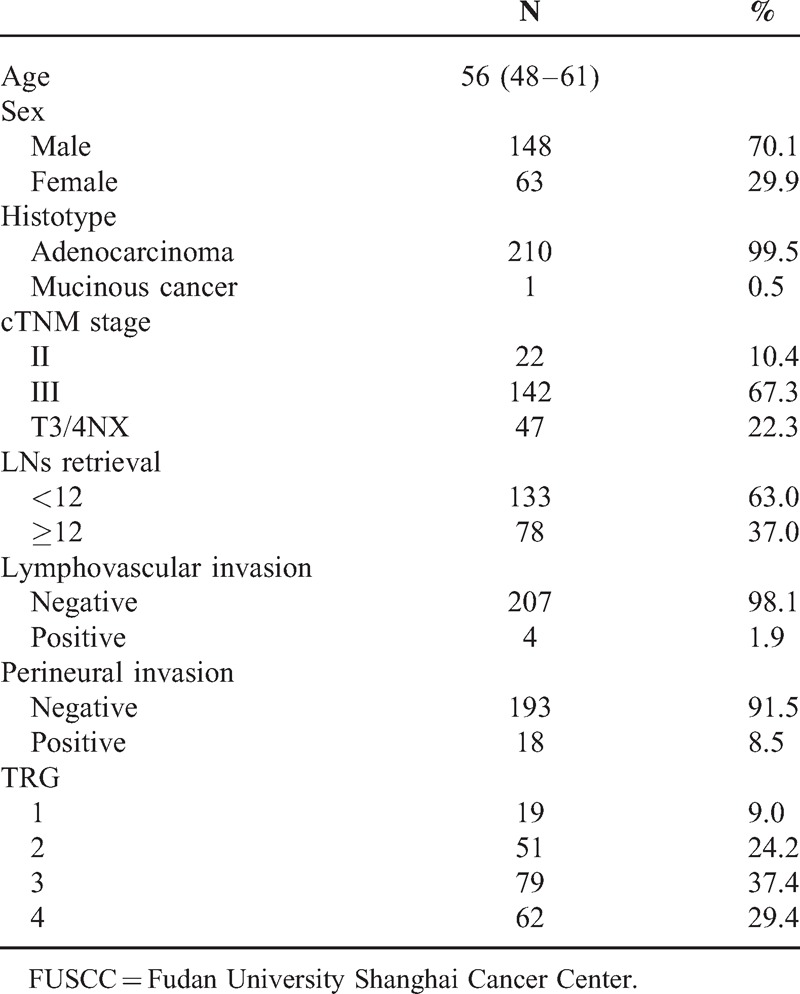

These results should be treated with caution because they could be biased by confounding factors, such as NCRT response and quality of surgery. To evaluate the reliability of SEER results, we studied relevant issues in 211 eligible patients from the FUSCC. Patient demographics and pathological features are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Demographic and Clinical Features for Patients With Rectal Cancer (ypN0) From FUSCC

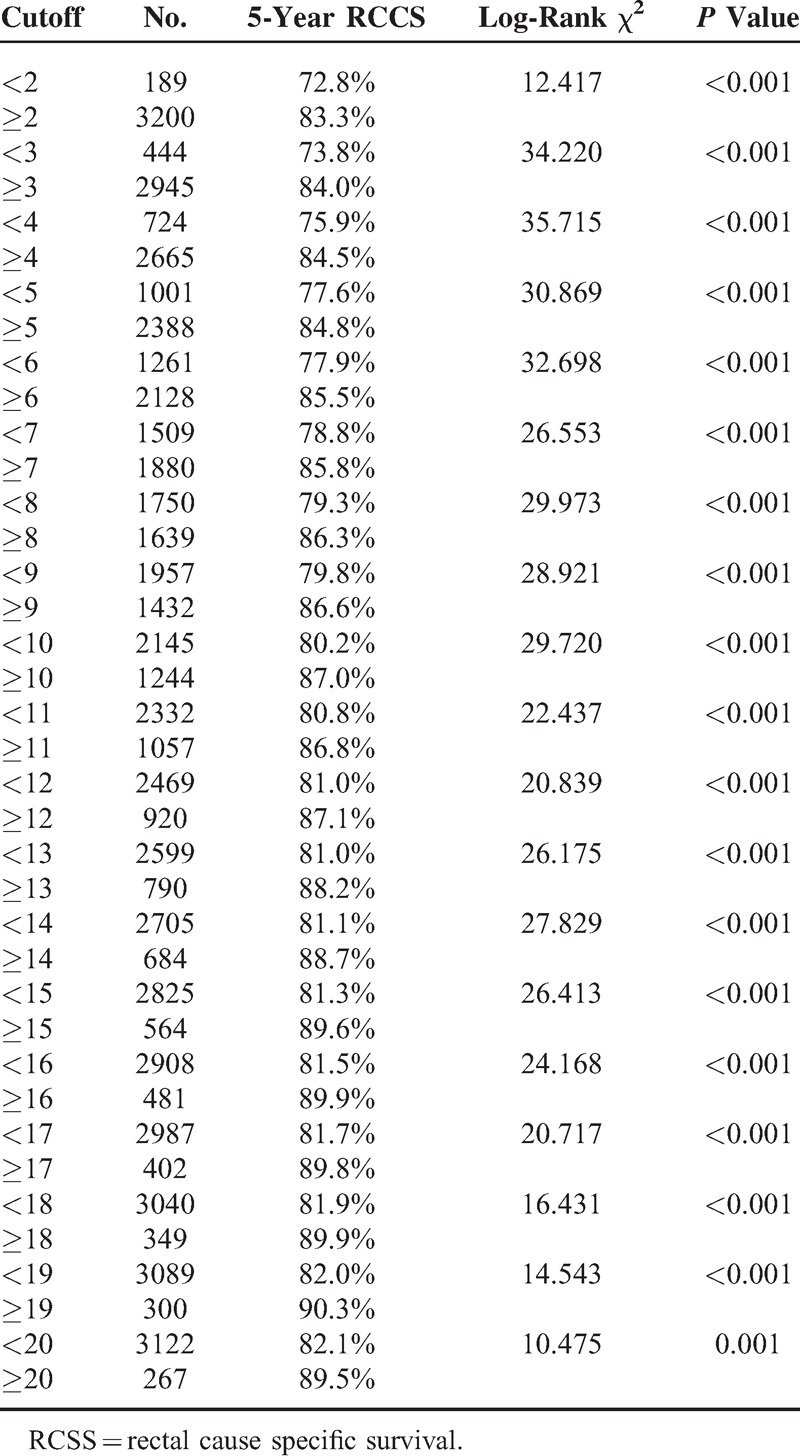

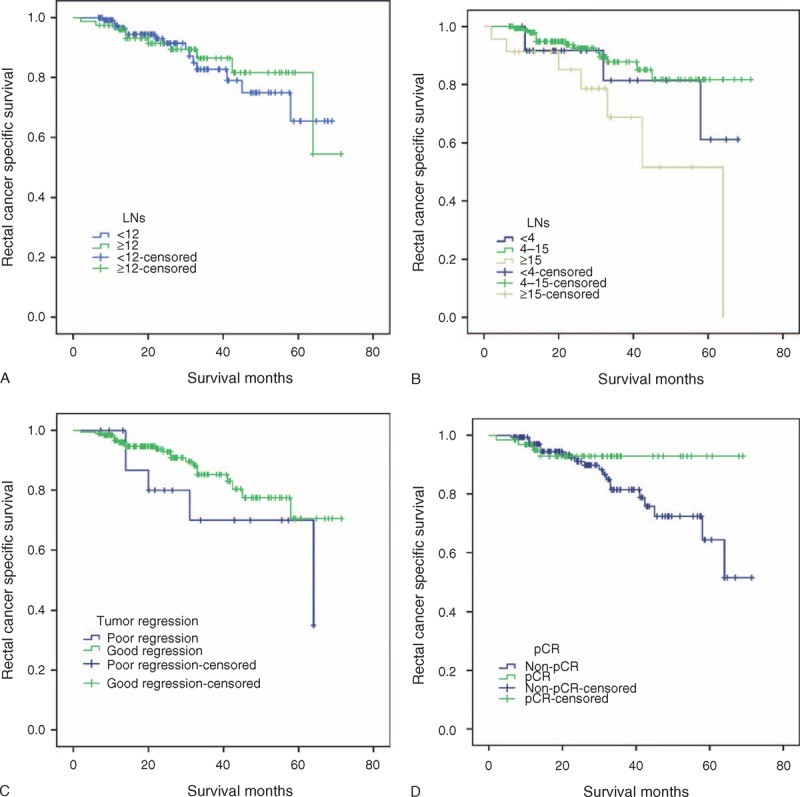

First, we studied 12 LNs cutoff in FUSCC. Three-year RCSS in patients with <12 and >12 LNs was 82.7% and 86.5%, respectively, which difference was not statistical (χ2 = 0.045, P = 0.832) (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Survival curves in rectal cancer patients at ypN0 stage according to different factors in FUSCC. (A) LNs retrieval <12 versus ≥12, χ2 = 0.05, P = 0.83; (B) Using 4 and 15 as LNs cutoff, χ2 = 7.90, P = 0.02; (C) Poor regression (TRG1) versus good regression (TRG2–4),χ2 = 1.88, P = 0.17; (D) pCR versus non-pCR, χ2 = 2.17, P = 0.14. FUSCC = Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center, LN = lymph nodes.

Second, we test 4 and 15 LNs cutoff in FUSCC. Three-year RCSS in patients with <4 LNs,4 to 15 LNs and ≥15LNs retrieval was 81.5%, 87.8%, 68.8%, which had statistically difference (χ2 = 7.90, P = 0.02). What interesting is patients with ≥15LNs dissected had worse 3-year RCSS than those with 4 to 15 LNs dissected (χ2 = 7.84, P = 0.01),and the differences between <4 LNs and 4 to 15 LNs dissected(χ2 = 0.80, P = 0.37), between <4 LNs and ≥15LNs dissected (χ2 = 1.78, P = 0.18) were not statistical (Figure 3B).

Third, we investigated the clinical relevance of LNs number and TRG after preop-RT for rectal cancer. TRG 4, 3, 2, 1 was found in 62 (29.4%), 79 (37.4%), 51 (24.2%), and 19 (9.0%) of the resected specimens, respectively. The median number of LNs retrieval was 9.23 for TRG4, 9.04 for TRG3, 9.35 for TRG2 and 11.95 for TRG1, respectively. There were significantly less LNs retrieval in good regression (TRG2–4) than poor regression (TRG1) (t = 2.40, P = 0.01). Compared with ≥12 LNs retrieval, higher proportion of good regression (TRG2–4) (95.49% vs 83.33%) was found in those with <12 LNs retrieval (χ2 = 8.87, P = 0.00) (Figure 3C).

Finally, we evaluated the correlation between TRG and RCSS. Three-year RCSS in patients with poor regression (TRG1) was lower than those who had good regression (TRG2–4), but the difference was not statistical (70.0% vs 85.3%, χ2 = 1.88, P = 0.17). Patients of pCR had better 3-year RCSS than non-pCR(92.9% vs 81.4%), although it failed statistical significance(χ2 = 2.17, P = 0.14),the difference between good and poor NCRT response is clearly (Figure 3D).

DISCUSSION

Preop-RT followed by surgical resection is the current standard practice for patients with rectal cancer with T3 or T4 tumors and/or positive lymph nodes. An increasing body of data suggests the superiority of preop-RT with regard to the local control, disease-free survival, and the ability to perform sphincter-sparing resection.2,3,18,19 The NCCN guideline recommends the examination of at least 12 LNs for patients with rectal cancer.20 Unfortunately, the impact of preop-RT on the number of examined LNs has not be fully elucidated. In this study, on average, 2 less LNs were examined in patients with preop-RT compared with patients without preop-RT. Our study verified statistically significant reduction in the number of LNs has been harvested after preop-RT.

The proportion of patients with recommended adequate nodal retrieval (≥12) by NCCN among patients with preop-RT was relatively low in both SEER (27.15%) and FUSCC dataset (37.0%). Our results are consistent with previous studies on the effect of preop-RT on LNs retrieval. In a study of 286 patients at a single institution, 188 underwent preop-RT and 98 went directly to surgery, the number of LNs retrieved was significantly lower in the preop-RT treated group (17.2 vs 14.6,P < 0.05).21 Similar results were reported by Wang et al22 and in the Dutch Total Mesorectal Excision trial.23 Many factors may be associated with the reduction of LNs number retrieved. Preop-RT influences LNs status by the effect of tumor cell killing effect and significantly reduces the number of harvested LNs by apoptosis and nodal involution induction of LNs.21,22,24–26 The immune response and fibrosis in LNs also contribute to the difficult in identification of nodes in the specimen.27 Neoadjuvant therapies may decrease the size of nonmetastatic LNs by 1 to 2 mm,28–30 and thus may decrease their likelihood to be detected in the surgical specimen.

In the current AJCC Staging system, examination of at least 12 LNs in rectal cancer is essential for avoiding underestimation of nodal staging. With the reduction in LNs harvest after preop-RT, this benchmark may not be suitable any longer. For optimal cutoff number of LNs retrieved was initially validated to assess survival and guide clinical practice, in this study, we identified 4 and 15 as optimal cutoff to divide ypN0 rectal cancer patients into high, middle and low risk subgroups and there was an absolute 13.7% improvement in 5-year RCSS if ≥ 15 LNs were analyzed than those <4. Previous study by Le et al31 identified 8 as optimal cutoff in ypN0 patients. But some other authors could not identify optimal LNs number in rectal cancer with preop-RT.32,33 Our large population-based study may make our conclusions more convincing.

LNs yield is also a good evaluation criterion for regional lymphadenectomy, which has been shown to be an independent prognostic factor in rectal cancers.5,34 Both surgical oncologists and pathologists play important roles in adequate LNs examined. A thorough LN dissection can not only reduce the possibility of local recurrence, but also guaranty the accurate staging of disease after surgery. This is important for further prognostic evaluation and subsequent adjuvant treatment. Moreover, surgeon is a technician, and perhaps those patients who each had more LNs identified in their specimens had a more complete excision of their tumor and the draining nodes. In rectal cancer resections, the technical considerations are more complicated than colon cancer.35 Improved surgical technique may reduce chance of iatrogenic spread of cancer cell. As such, there would be less likelihood of leaving tumor behind and thus affecting survival. A greater number of recovered LNs may be an indicator of quality of surgical care or pathological examination.

Conversely, less nodal counts may increase the risk of understage. We found patients with extremely low LNs counts (2 LNs) had a very low 5-year RCSS than the others. This might be the result of a poor quality control of radical lymphadenectomy and understaged. It might occur that, however, after a certain cutoff, any increase in number of LNs examined will no longer have influence on the accuracy of staging and survival. Thus, we recommended that a minimal number of 15 LNs be retrieved in ypN0 patients.

Previous study had shown that the meaning of good tumor response in reduced number of LNs examined may offset the influence of potential understaged in rectal cancer patients with preop-RT,36 in FUSCC set, there was fewer LNs retrieval in good tumor regression than poor regression, but the survivals between the 2 group was not significantly difference. We deduced the risk of understaged may have overwhelmed effect on survival than that of good tumor response in reduced LN counts in patients with very few LNs retrieval. The sample size in FUSCC set was relatively small. This may reduce the statistical power. But we should still pay great caution that provided the standard principles of Total Mesorectal Excision technique and adequate pathologic examination, small LN count from patients treated with NCRT previously might be an indicator of good other than poor tumor response, which is associated with improved survival.

Although this is a large population-based study, it has several potential limitations. Firstly, SEER database does not include information on the administration of chemotherapy. The additional or concurrent chemotherapy might reduce more LNs numbers retrieval than preop-RT alone. Secondly, our study was performed using 2 retrospective databases rather than prospective cohorts; this approach might introduce sampling biases. Lastly, the therapeutic strategy of multidisciplinary treatment on advanced rectal cancer has not well organized until 2005 worldwide. Thus, the exact dose, duration and administration of radiation therapy may be different from nowadays’.

In summary, our study revealed that preop-RT significantly decreases the number of LNs retrieved from patients with ypN0 stage rectal cancer. This may weaken the power of established guideline of at least of 12 LNs retrieval for proper nodal staging. But the number of LNs is still an independently prognostic factor for ypN0 rectal cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer, CRC = colorectal cancer, CSS = cause-specific survival, FUSCC = Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center, LN = lymph node, NCRT = neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy, preop-RT = preoperative radiation, SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results, TRG = tumor regression grade.

QL and CZ contributed equally to this work.

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81001055, 81101586, 81201836 and 81472222), Shanghai Pujiang Program (No.13PJD008, 12PJD015, 12PJ1401800), National High Technology Research and Development Program (863 Program, No.2012AA02A506), and Shanghai Shenkang Program (No. SHDC12012120). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014; 64:9–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:638–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:1731–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim YW, Kim NK, Min BS, et al. The influence of the number of retrieved lymph nodes on staging and survival in patients with stage II and III rectal cancer undergoing tumor-specific mesorectal excision. Ann Surg 2009; 249:965–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tepper JE, O’Connell MJ, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Impact of number of nodes retrieved on outcome in patients with rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19:157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xingmao Z, Hongying W, Zhixiang Z, et al. Analysis on the correlation between number of lymph nodes examined and prognosis in patients with stage II colorectal cancer. Med Oncol 2013; 30:371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rullier A, Laurent C, Capdepont M, et al. Lymph nodes after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal carcinoma: number, status, and impact on survival. Am J Surg Pathol 2008; 32:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wichmann MW, Muller C, Meyer G, et al. Effect of preoperative radiochemotherapy on lymph node retrieval after resection of rectal cancer. Arch Surg 2002; 137:206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taflampas P, Christodoulakis M, Gourtsoyianni S, et al. The effect of preoperative chemoradiotherapy on lymph node harvest after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2009; 52:1470–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leibold T, Shia J, Ruo L, et al. Prognostic implications of the distribution of lymph node metastases in rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:2106–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camp RL, Dolled-Filhart M, Rimm DL. X-tile: a new bio-informatics tool for biomarker assessment and outcome-based cut-point optimization. Clin Cancer Res 2004; 10:7252–7259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunderson LL, Jessup JM, Sargent DJ, et al. Revised tumor and node categorization for rectal cancer based on surveillance, epidemiology, and end results and rectal pooled analysis outcomes. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28:256–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao P, Song YX, Wang ZN, et al. Is the prediction of prognosis not improved by the seventh edition of the TNM classification for colorectal cancer? Analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database. BMC Cancer 2013; 13:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Appleby DH, Zhang X, et al. Comparison of three lymph node staging schemes for predicting outcome in patients with gastric cancer. Br J Surg 2013; 100:505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu Y, Hu C, Zhang H, et al. How does the number of resected lymph nodes influence TNM staging and prognosis for esophageal carcinoma? Ann Surg Oncol 2010; 17:784–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dworak O, Keilholz L, Hoffmann A. Pathological features of rectal cancer after preoperative radiochemotherapy. Int J Colorectal Dis 1997; 12:19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodel C, Martus P, Papadoupolos T, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23:8688–8696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu JY, Xiao Y, Qiu HZ, et al. Clinical outcome of neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy with oxaliplatin and capecitabine or 5-fluorouracil for locally advanced rectal cancer. J Surg Oncol 2013; 108:213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roh MS, Colangelo LH, O’Connell MJ, et al. Preoperative multimodality therapy improves disease-free survival in patients with carcinoma of the rectum: NSABR-03. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:5124–5130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engstrom PF, Arnoletti JP, Benson AB, 3rd, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: rectal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2009; 7:838–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de la Fuente SG, Manson RJ, Ludwig KA, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation for rectal cancer reduces lymph node harvest in proctectomy specimens. J Gastrointest Surg 2009; 13:269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang H, Safar B, Wexner S, et al. Lymph node harvest after proctectomy for invasive rectal adenocarcinoma following neoadjuvant therapy: does the same standard apply? Dis Colon Rectum 2009; 52:549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, Klein Kranenbarg E, et al. No downstaging after short-term preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19:1976–1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baxter NN, Morris AM, Rothenberger DA, et al. Impact of preoperative radiation for rectal cancer on subsequent lymph node evaluation: a population-based analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005; 61:426–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thorn CC, Woodcock NP, Scott N, et al. What factors affect lymph node yield in surgery for rectal cancer? Colorectal Dis 2004; 6:356–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morcos B, Baker B, Al Masri M, et al. Lymph node yield in rectal cancer surgery: effect of preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol 2010; 36:345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scabini S, Montecucco F, Nencioni A, et al. The effect of preoperative chemoradiotherapy on lymph nodes harvested in TME for rectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol 2013; 11:292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sprenger T, Rothe H, Homayounfar K, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy does not necessarily reduce lymph node retrieval in rectal cancer specimens: results from a prospective evaluation with extensive pathological work-up. J Gastrointest Surg 2010; 14:96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez RO, Pereira DD, Proscurshim I, et al. Lymph node size in rectal cancer following neoadjuvant chemoradiation: can we rely on radiologic nodal staging after chemoradiation? Dis Colon Rectum 2009; 52:1278–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koh DM, Chau I, Tait D, et al. Evaluating mesorectal lymph nodes in rectal cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemoradiation using thin-section T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008; 71:456–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le M, Nelson R, Lee W, et al. Evaluation of lymphadenectomy in patients receiving neoadjuvant radiotherapy for rectal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19:3713–3718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mekenkamp LJ, van Krieken JH, Marijnen CA, et al. Lymph node retrieval in rectal cancer is dependent on many factors: the role of the tumor, the patient, the surgeon, the radiotherapist, and the pathologist. Am J Surg Pathol 2009; 33:1547–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ha YH, Jeong SY, Lim SB, et al. Influence of preoperative chemoradiotherapy on the number of lymph nodes retrieved in rectal cancer. Ann Surg 2010; 252:336–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai CJ, Crane CH, Skibber JM, et al. Number of lymph nodes examined and prognosis among pathologically lymph node-negative patients after preoperative chemoradiation therapy for rectal adenocarcinoma. Cancer 2011; 117:3713–3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McFadden C, McKinley B, Greenwell B, et al. Differential lymph node retrieval in rectal cancer: associated factors and effect on survival. J Gastrointest Oncol 2013; 4:158–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Campos-Lobato LF, Stocchi L, de Sousa JB, et al. Less than 12 nodes in the surgical specimen after total mesorectal excision following neoadjuvant chemoradiation: it means more than you think!. Ann Surg Oncol 2013; 20:3398–3406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]