Abstract

Enterovirus (EV) infection is a major public health issue throughout the world with potential neurological complications. This study evaluated the relationship between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and EV encephalitis in children.

Data of reimbursement claims from the National Health Insurance Research Database of Taiwan were used in a population-based case–control design. The study comprised 2646 children with ADHD who were matched according to sex, age, urbanization level of residence, parental occupation, and baseline year, to people without ADHD at a ratio of 1:10. The index date of the ADHD group was the ADHD date of diagnosis. Histories of EV infections before the index dates were collected and recategorized according to the severity of infection.

Compared with children without EV infection, the children with mild EV infection had a 1.16-fold increased risk of ADHD (odds ratio [OR] = 1.16, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.07–1.26), and the children with severe EV infection had a greater risk of ADHD (OR = 2.82, 95% CI = 1.05–7.57). The results also revealed a significant correlation between ADHD and the severity of EV infection (P for trend = 0.0001).

Patients with EV encephalitis have an increased risk of developing ADHD. Although most EV encephalitis in children has a favorable prognosis, it may be associated with significant long-term neurological sequelae, even in children considered fully recovered at discharge. Neuropsychological testing should be recommended for survivors of childhood EV encephalitis. The causative factors between EV encephalitis and the increased risk of ADHD require further investigation.

INTRODUCTION

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common disorder in preschool and school-aged children.1 Although genetic factors account for 80% of the etiology of ADHD,2 multiple pre-, peri-, and postnatal factors can result in ADHD. Numerous experimental and clinical studies have correlated the sites of brain damaged with the symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity.3,4 Recent studies have indicated that there may be a relationship between individuals suffering from ADHD and traumatic brain injuries5 and an association with seasonally mediated viral infections 6,7, including HIV, enterovirus (EV) 71, and varicella zoster encephalitis.8–10

EV infections are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.11 The EV genus is part of the picornavirus family and includes notable members such as poliovirus, coxsackievirus, and EV71. Diseases caused by EV are not restricted to poliomyelitis; nonpolio EVs are known to target the central nervous system (CNS) and are responsible for numerous clinical manifestations including encephalitis and meningitis.12 Several previous large studies on encephalitis cases have found that EVs are among the major known causes of encephalitis.12,13

EV encephalitis generally has a favorable prognosis14; however, in 1998, an epidemic of hand-foot-and-mouth disease caused by EV71 affected thousands of children in Taiwan.15 The primary neurological complication was rhombencephalitis, which had a fatality rate of 14%. In 2000, the Taiwan centers for disease control developed a disease management program that had effectively controlled EV infection and reduced impacts of the disease to the society.16,17 However, long-term sequelae of neuropsychiatric problems have remained a major concern. In a recent study, Gau et al18 examined the outcome of 86 children who had neurological complications because of EV71 infections during the Taiwan epidemic and found that the prevalence of symptoms related to ADHD was 20%, whereas among matched control subjects, it was only 3%.

Based on our review, the data on the long-term neurological outcomes of children with EV encephalitis are limited. Most related studies have estimated the outcomes by using clinical follow-up assessments at outpatient clinics19,20 and structured questionnaires.21 In addition, most studies have been conducted in clinical settings and have not included large populations. The current study investigated the relationship between ADHD and EV encephalitis by using population-based data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), based on the hypothesis that EV encephalitis increases the risk of ADHD.

METHODS

Data Source

In 1995, the Taiwan government launched the Taiwan National Health Insurance program, which is a nationwide single-payer health insurance program that covers >99% of Taiwan's 23 million residents since 1998. The National Health Research Institute (NHRI) created and manages the NHIRD, which contains all historical reimbursement claims data. The NHRI encrypted all personal identification information to protect patient privacy before releasing the data for research. This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board at China Medical University (CMU-REC-101–012).

The Longitudinal Health Insurance Database (LHID) was used for this research. The LHID is a subset of the NHIRD. The NHRI randomly sampled 1 million beneficiaries from the NHIRD; the sample comprised annual reimbursement claims records, which included medical service records and information on the sex, date of birth, and occupation of the beneficiaries. According to an NHRI report, the age and sex distributions were similar between the LHID and the NHIRD. Because the identification information is encoded, the NHRI provided anonymous identification numbers for each patient's claims data.

In NHIRD, all disease records of the insured subjects were written in outpatient (including emergency department visits) and inpatient files. The disease history of the study population was collected from these files. The disease diagnosis in the NHIRD is based on the criteria of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM).

Study Population

This study was a population-based case–control design. Children aged <18 years who were diagnosed with ADHD (ICD-9-CM 314) from 2006 to 2010 were selected for the ADHD group of this study. The NHIRD recorded the disease diagnoses by using the ICD-9-CM.22–24 The index date of the ADHD group was the date of ADHD diagnosis. The 10-fold control group was selected and frequency-matched according to age (every 3 years), sex, urbanization level, and parents’ occupation. The date of the control was the month and index year of the matched case.

The risk factor assessed was EV infection (ICD-9-CM 074, 047, and 048). The ICD-9-CM codes are as following: 047 (meningitis due to EV); 048 (EV disease of CNS); and 074 (specific diseases due to Coxsackie virus). We collected data on EV infections before the index date. The EV infections were categorized according to severity. A severe EV infection was defined as EV infection combined with encephalitis (ICD-9-CM 323.0, 323.4, 323.9) within 1 month of infection. Children who were infected only with EV were defined as having a mild EV infection, that is, infection but without complication of encephalitis. We also calculated the frequency of EV infections diagnosed before index date and grouped into 4 levels: none, <4 times, 4 to 5 times, and ≧6 times.

The urbanization level was defined according to several indices including the population density (people/km2), population ratio of different educational levels, population ratio of elderly people, population ratio of agricultural workers, and number of physicians per 100,000 people.25 Urbanization was categorized into 4 levels, with Level 1 being the highest degree of urbanization and Level 4 the lowest. Parental occupation was classified as white collar (those working most hours indoors, such as institutional workers, office workers, and civil service employees), blue collar (those working most hours outdoors or as industrial laborers, farmers, fishermen, and factory workers), or other (eg, retired).

Statistical Analysis

The distribution of demographic factors and cases of EV infection were presented as a number and percentage. The difference in the demographic distribution between the case and the control groups was examined using the chi-squared test. To demonstrate the risk of ADHD for children with and without EV infection, we estimated the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) by using an unconditional logistic regression model. The logistic regression was also applied to the stratified analysis to assess the ADHD risk for subjects with different demographic factors.

Data management and statistical analysis were performed using SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The significant level was set at less than 0.05 for two-sided P values.

RESULTS

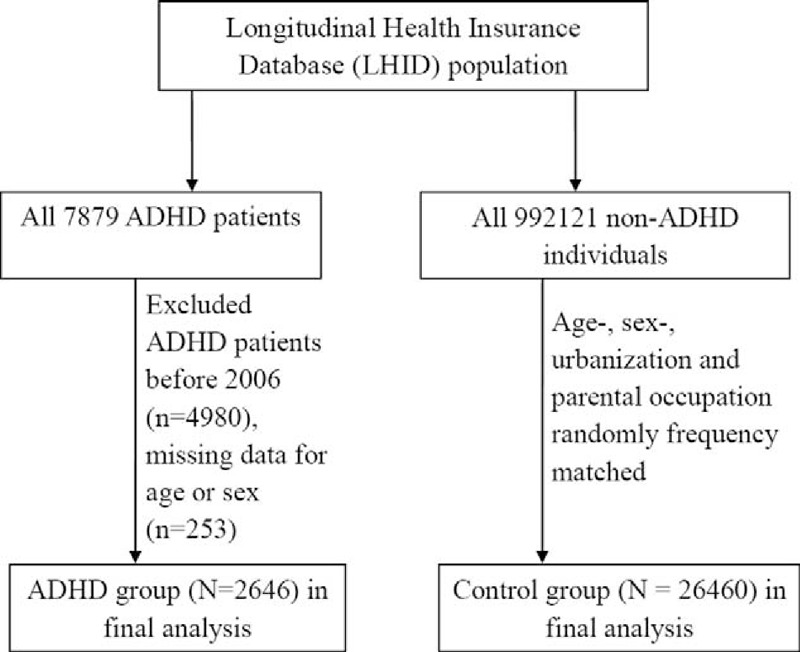

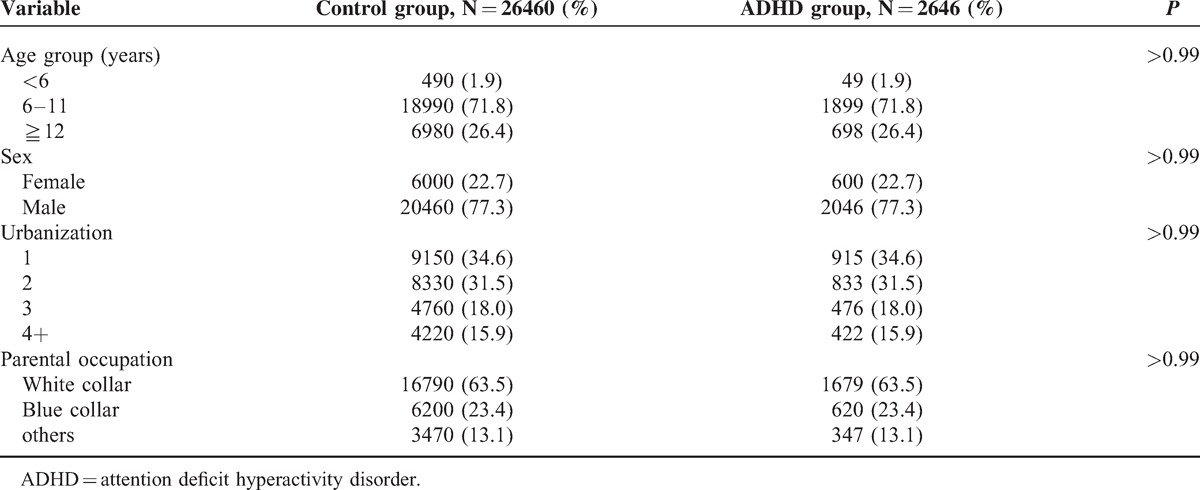

The study population consisted of 2646 children diagnosed with ADHD and 26,460 children without ADHD (Figure 1, Table 1). All types of EV virus were included in the study. Over 98% of the subjects were older than 6 years and 77% were male. Most of the subjects (66.1%) lived in areas of high-level urbanization (Levels 1 and 2) and most parental occupations were white-collar workers. The mean of the duration from the initial EV infection to ADHD diagnosed was 6.1 years (standard deviation = 2.4 years).

FIGURE 1.

The flow chart to describe the study design and study subjects’ selection.

TABLE 1.

The Distribution of Demographic Status Compared Between Control and ADHD Group

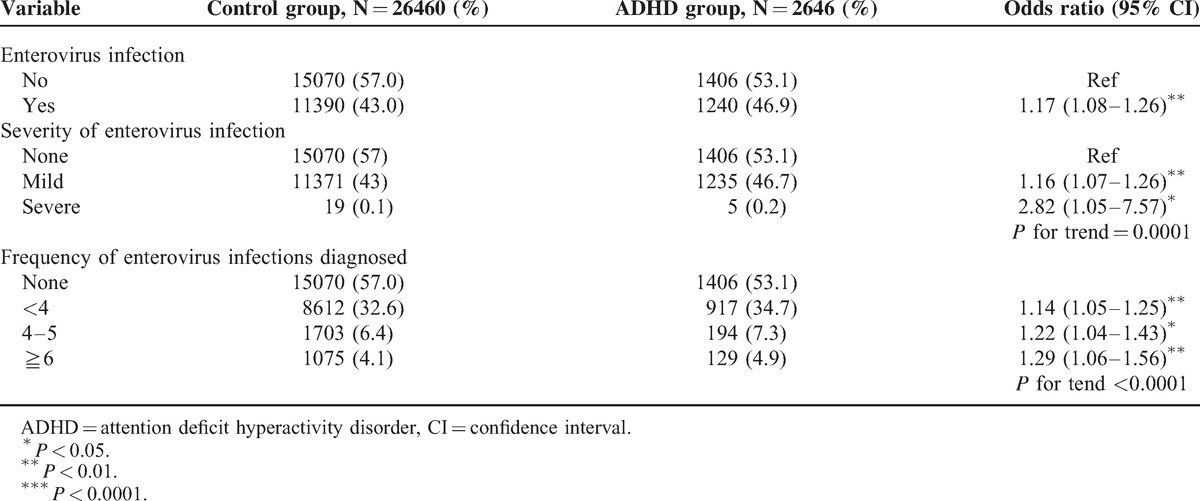

Nearly 47% of the children with ADHD had EV infection. The proportion of subjects who had EV infection in the control group (43%) was lower than that in the ADHD group (Table 2). Compared with the children without EV infection, the children with EV infection had a 1.17-fold increased risk of ADHD (OR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.08–1.26). Compared with the children without EV infection, the children with mild infection had a 1.16-fold increased risk of ADHD (OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.07–1.26), and the children with severe EV infection had a greater risk of ADHD (OR = 2.82, 95% CI = 1.05–7.57). We also observed a trend that the ADHD risk was increased with severity of the EV infection (P for trend = 0.0001). Compared with the individuals without EV infection, the individuals with <4, 4 to 5, and ≧6 times EV diagnosis had a 1.14-fold (95% CI = 1.05–1.25), a 1.22-fold (95% CI = 1.04–1.43), and a 1.29-fold (95% CI = 1.06–1.56) increased risk of ADHD, respectively. The results revealed that the ADHD risk was increased with increased frequency of EV infections.

TABLE 2.

Logistic Regression Analysis Measured Odds Ratio for the ADHD Risk Between the Children With and Without Enterovirus Infection

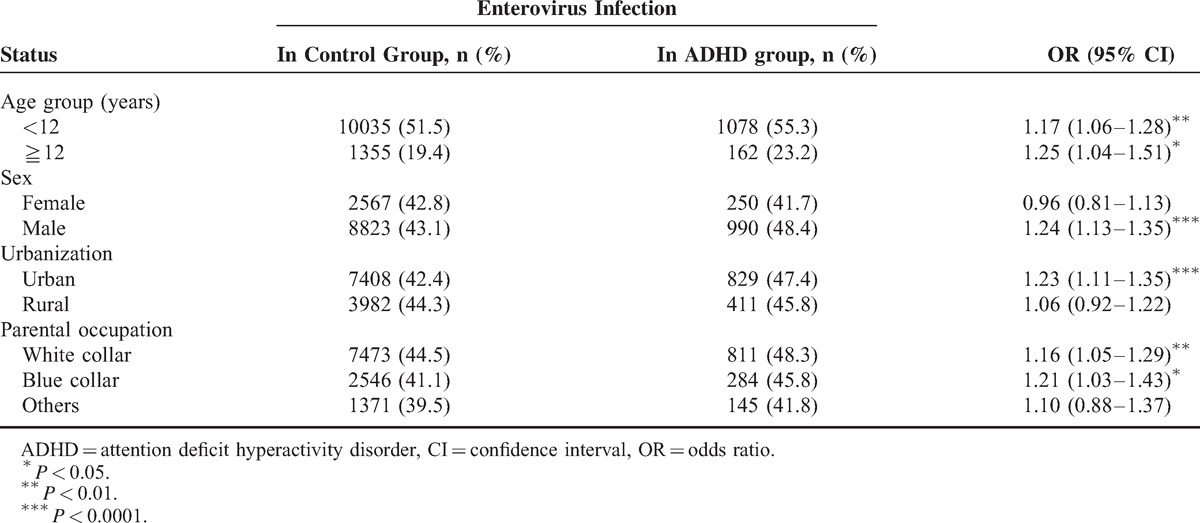

Table 3 shows the ADHD risk of children with and without EV infection, stratified according to different demographic factors. The children with EV infection were significantly associated with an increased risk of ADHD compared with the children without EV infection (with different status of demographic factors except for the following: female, lived in rural areas, and nonwhite- and nonblue-collar parent occupation).

TABLE 3.

Logistic Regression Analysis Measured OR for Study Group Stratified Different Demographic Factors

DISCUSSION

ADHD is a neurobiological syndrome with an estimated prevalence of 5% among children and adolescents.26 The specific genes may be responsible for most causes of ADHD. However, other risk factors for ADHD may influence brain development and functioning such as acquired brain injury due to trauma or disease. Identifying the risk factors for ADHD is necessary for implementing prevention strategies.

This study found that patients with EV encephalitis have an increased risk of developing ADHD (OR = 2.82, 95% CI = 1.05–7.57). This result is consistent with that of a previous study on encephalitis, that early childhood is associated with behavioral and psychotic disorders.27 A Swedish national cohort study on 1.2 million children used Swedish national registers to retrieve data on hospital admissions for CNS infections, revealing a slightly increased risk of nonaffective psychotic illnesses and schizophrenia associated with viral CNS infections. In addition, some serotypes, such as EV71, are associated with severe diseases and outcomes, as well as an increased prevalence of hyperactivity/impulsivity and attention deficit/hyperactivity.17 Recently, Michaeli et al28 reported that acute encephalitis in children may lead to significant long-term neurological sequelae; in their study, 50% of the patients suffered from ADHD and 20% suffered from learning disabilities.

The pathogenesis of EV encephalitis is diverse and not completely understood. Immune responses to viral infections produce various cytokines. The clinical presentation of EV encephalitis seems to be caused by a hyperinflammatory syndrome resulting from hypercytokinemia and CNS inflammation of various inflammatory mediators.29,30 Children with CNS infection may suffer from inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity when the prefrontal lobe and its connection to the striatum, parietal lobe, cerebellum, and other circuits are involved.31 They may also suffer from emotional problems when the function of brain areas such as the amygdala and nucleus accumbens is affected.32

Using a population-based study with high representation under the single-buyer of the government in Taiwan and including a very large sample size are the strengths of this study. In addition, the diagnoses in the NHIRD are highly reliable because of strict survey by qualified specialists and under peer review. However, there are some study limitations: no detailed data of subjects’ lifestyle, habits, body mass index, physical activity, socioeconomic conditions, or family history; the quality of a cohort study is lower than that of a randomized trial; the NHI claims are not for studies’ purposes and lack of the identified numbers to directly contact the study subjects.

In conclusion, our results show that patients with EV encephalitis are associated with a higher prevalence of ADHD. Although most EV encephalitis in children have a favorable prognosis, there may be significant long-term neurological sequelae even in children who were considered fully recovered at discharge. Neuropsychological testing should be recommended for survivors of childhood encephalitis. The causative factors between ADHD and the increased risk of EV encephalitis require further investigation.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, CI = confidence interval, CNS = central nervous system, EV = Enterovirus, ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, LHID = Longitudinal Health Insurance Database, NHIRD = National Health Insurance Research Database, NHRI = National Health Research Institute, OR = odds ratio.

Contributor's Statement: Conception/design: I-CC, C-HK.

Provision of study materials: C-HK.

Collection and/or assembly of data: I-CC, C-HK.

Data analysis and interpretation: C-CL.

Manuscript writing: All authors.

Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

This study is supported in part by China Medical University Hospital (DMR-104-028), Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence (MOHW104-TDU-B-212-113002); China Medical University Hospital, Academia Sinica Taiwan Biobank, Stroke Biosignature Project (BM104010092); NRPB Stroke Clinical Trial Consortium (MOST 103-2325-B-039 -006); Tseng-Lien Lin Foundation, Taichung, Taiwan; Taiwan Brain Disease Foundation, Taipei, Taiwan; Katsuzo and Kiyo Aoshima Memorial Funds, Japan; and Health, and welfare surcharge of tobacco products, China Medical University Hospital Cancer Research Center of Excellence (MOHW104-TDU-B-212-124-002, Taiwan). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. No additional external funding received for this study.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mental health in the United States: Prevalence of diagnosis and medication treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. United States, 2003. MMWR 2005; 54:842–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biederman J, Faraone SV. Current concepts on the neurobiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Atten Disord 2002; 6:S7–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Livingston RB, Fulton JF, Delgado JMR. Fulton JF, et al. Stimulation and regional ablation of orbital surface of frontal lobe. The Frontal Lobes. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins Company; 1948; 27:405-420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millichap JG, et al. Historical overview of ADHD. Progress in Pediatric Neurology, III 1997; Chicago, IL: PNB, 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 5.English T. The after effects of head injuries. Lancet 1904; 1:485–489. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hohman LB. Post-encephalitic behavior disorders in children. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 1922; 380:372–375. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebaugh F. Neuropsychiatric sequelae of acute epidemic encephalitis in children. Am J Dis Child 1923; 25:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nozyce ML, Lee SS, Wiznia A, et al. A behavioral and cognitive profile of clinically stable HIV-infected children. Pediatrics 2006; 117:763–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang LY, Huang LM, Gau SSF, et al. Neurodevelopment and cognition in children after enterovirus 71 infection. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:1226–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dale RC, Church AJ, Heyman I. Striatal encephalitis after varicella zoster infection complicated by Tourettism. Mov Disord 2003; 18:1554–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhoades RE, Tabor-Godwin JM, Tsueng G, et al. Enterovirus infections of the central nervous system. Virology 2011; 411:288–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michos AG, Syriopoulou VP, Hadjichristodoulou C, et al. Aseptic meningitis in children: analysis of 506 cases. PLoS One 2007; 2:e674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fowlkes AL, Honarmand S, Glaser C, et al. Enterovirus-associated encephalitis in the California Encephalitis Project, 1998–2005. J Infect Dis 2008; 198:1685–1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherry JD. Feigin RD, Cherry JD. Enteroviruses: coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, and polioviruses. Textbook of pediatric infectious diseases 4th ed.Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1998; 1787-839. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho M, Chen ER, Hsu KH, et al. An epidemic of enterovirus 71 infection in Taiwan. N Engl J Med 1999; 341:929–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin TY, Chang LY, Hsia SH, et al. The 1998 enterovirus 71 outbreak in Taiwan: pathogenesis and management. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 34:S52–S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang LY, Hsia SH, Wu CT, et al. Outcome of EV71 Infections with or without stage-based management, 1998 to 2002. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2004; 23:327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gau SS, Chang LY, Huang LM, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity-related symptoms among children with enterovirus 71 infection of the central nervous system. Pediatrics 2008; 122:e452–e458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rautonen J, Koskiniemi M, Vaheri A. Prognostic factors in childhood acute encephalitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1991; 10:441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang IJ, Lee PI, Huang LM, et al. The correlation between neurological evaluations and neurological outcome in acute encephalitis: a hospital-based study. Eur J Paediatr Neuro 2007; 11:63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ilias A, Galanakis E, Raissaki M, et al. Childhood encephalitis in Crete, Greece. J Child Neurol 2006; 21:910–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou IC, Lin CC, Sung FC, et al. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder increases the risk of deliberate self-poisoning: A population-based cohort. Eur Psychiatry 2014; 29:523–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chou IC, Lin CC, Sung FC, et al. Attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder increases risk of bone fracture: a population-based cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2014; 56:1111–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chou IC, Chang YT, Chin ZN, et al. Correlation between epilepsy and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a population-based cohort study. PLoS One 2013; 8:e57926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu CY, Hung YT, Chuang YL, et al. Incorporating development stratification of Taiwan townships into sampling design of large scale health interview survey. J Health Manag 2006; 14:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willcutt EG. The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review”. Neurotherapeutics 2012; 9:490–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dalman C, Allebeck P, Gunnell D, et al. Infections in the CNS during childhood and the risk of subsequent psychotic illness: a cohort study of more than one million Swedish subjects. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michaeli O, Kassis I, Shachor-Meyouhas Y, et al. Long-term motor and cognitive outcome of acute encephalitis. Pediatrics 2014; 133:e546–e552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin TY, Hsia SH, Huang YC, et al. Proinflammatory cytokine reactions in enterovirus 71 infections of the central nervous system. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 36:269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffiths MJ, Ooi MH, Wong SC, et al. In enterovirus 71 encephalitis with cardio-respiratory compromise, elevated interleukin 1β, interleukin 1 receptor antagonist, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor levels are markers of poor prognosis. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:881–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arnsten AF. Fundamentals of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: circuits and pathways. J Clin Psychiatry 2006; 67:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davidson RJ, Jackson DC, Kalin NH. Emotion, plasticity, context, and regulation: perspectives from affective neuroscience. Psychol Bull 2000; 126:890–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]