Abstract

Walled-off necrosis (WON) caused by fungal infection is very rare, and its treatment is more difficult than that of bacterial infection. We present the first case of a patient with refractory fungal-infected WON treated with percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy and local administration of amphotericin B.

A Japanese man in his 30s was hospitalized with severe necrotizing pancreatitis and multiple organ failure. Computed tomography imaging of the abdomen 1 month after the onset of pancreatitis revealed infected WON. Percutaneous drainage revealed purulent necrotic fluid, and culture of the fluid revealed the presence of Candida albicans and C glabrata. WON was treated by percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy and local administration of amphotericin B. Consequently, the patient's condition improved, and Candida species were not detected in subsequent cultures.

The combination of endoscopic necrosectomy with local administration of amphotericin B may be effective in treating refractory fungal-infected WON.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic and peripancreatic collections are typical late complications of acute pancreatitis. The revised Atlanta Classification1 classifies pancreatic and peripancreatic collections into 4 categories: acute peripancreatic fluid collection, pancreatic pseudocyst, acute necrotic collection, and walled-off necrosis (WON).

WON, which usually occurs more than 4 weeks after the onset of necrotizing pancreatitis, is a severe complication with particularly high mortality when secondarily infected.2 Open necrosectomy with drainage had been the standard treatment for infected WON. However, the risk of surgery is high when the presenting infection is severe, with high complication and mortality rates.3 Recently, minimally invasive endoscopic necrosectomy has been reported4 and has improved clinical outcomes. However, fatal cases have still been reported.

Here we present a case of refractory fungal-infected WON that failed to resolve despite 3 percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy procedures; however, it resolved with local administration of amphotericin B and perfusion lavage. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of fungal-infected WON to be successfully treated by local administration of amphotericin B. We present this case with a review of the literature.

CASE REPORT

A Japanese man in his 30s visited our hospital with postprandial upper abdominal pain. He had no medical or family history. Physical examination revealed marked abdominal tenderness and a temperature of 37.9°C. Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 28300/μL, C-reactive protein level of 3.61 mg/dL, and serum amylase level of 4846 IU/L. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed enlargement of the pancreas, inflammatory changes in the peripancreatic fat, poor enhancement of the parenchyma of the pancreatic body and tail, and inflammatory changes spreading from the pancreas to the lower abdominal cavity (Figure 1). Therefore, he was diagnosed with acute severe necrotizing pancreatitis. He also had evidence of multiple organ failure. Although his condition gradually improved with intensive care, it deteriorated 1 month after the onset of pancreatitis. At this point, he developed a temperature of 39°C, abdominal pain, an elevated white blood cell count (27100/μL), and an elevated C-reactive protein level (30.65 mg/dL). Abdominal CT revealed WON in the pancreatic body/tail and peripancreatic area, and it was presumed to be secondarily infected (Figure 2A). Because of the clinical deterioration and severe infection, we were unable to perform endoscopic treatment. Therefore, we punctured WON by ultrasound (US) guidance and initiated percutaneous drainage, which produced purulent necrotic fluid. The initial culture revealed the presence of Enterococcus gallinarum, and we initiated intravenous antibacterial therapy with meropenem (3 g daily). However, we were unable to control the infection. Although additional treatment, including the addition of drainage catheters and necrosectomy, was necessary, he developed severe cerebral infarction requiring decompressive hemicraniectomy, which precluded aggressive treatment. The cause of cerebral infarction was unidentified, although metabolic abnormality with severe pancreatitis may be related to the onset of cerebral infarction. Approximately 4 weeks after the initial drainage, his cerebral infarction slightly improved. However, repeat CT showed that WON had extended (Figure 2B); therefore, 2 additional percutaneous drainage catheters were inserted in his left flank. In addition, we performed perfusion lavage of WON with saline via the drainage catheters. Purulent necrotic fluid from WON was again for culture; Candida albicans and C glabrata were detected. His serum (1,3)-β-d-glucan level increased to 33 pg/mL (normal: ≤11 pg/mL). Therefore, we initiated intravenous antifungal therapy with caspofungin (50 mg daily). Subsequently, we performed endoscopic necrosectomy via the percutaneous fistula (Figure 3) after the patient provided informed consent. The percutaneous fistula was dilated up to 15 mm using a large balloon (CRE balloon dilator; Boston Scientific Corp, Natick, MA). Following this, we inserted the water jet endoscope (GIF-Q260J; Olympus Medical Systems Corp, Tokyo, Japan) into the cavity and removed the necrotic tissue using a snare, net, or basket catheter with CO2 insufflation. No complications were observed. We removed as much necrotic tissue as possible on 3 separate occasions; however, the elevated temperature persisted, and his serum (1,3)-β-d-glucan level increased to 95 pg/mL. At necrosectomy, because a fungal nest that was not removed by necrosectomy remained adhered to the wall of WON (Figure 4), we speculated that the intravenous antifungal agents were unable to reach that nest. Therefore, we initiated a local administration of amphotericin B (100 mg) and saline perfusion lavage 3 times a day (Figure 5). Drainage catheters were clamped for 1–2 hours after every local administration of amphotericin B. The patient's condition subsequently improved; he became apyrexial, his serum (1,3)-β-d-glucan level became normal, and culture of the WON fluid revealed no further Candida species. The drainage catheters were removed and antifungal treatment was stopped 3 months after the diagnosis of infected WON (Figure 6). No side effect of amphotericin B was observed. The fistula was closed naturally, and no further recurrence has been observed.

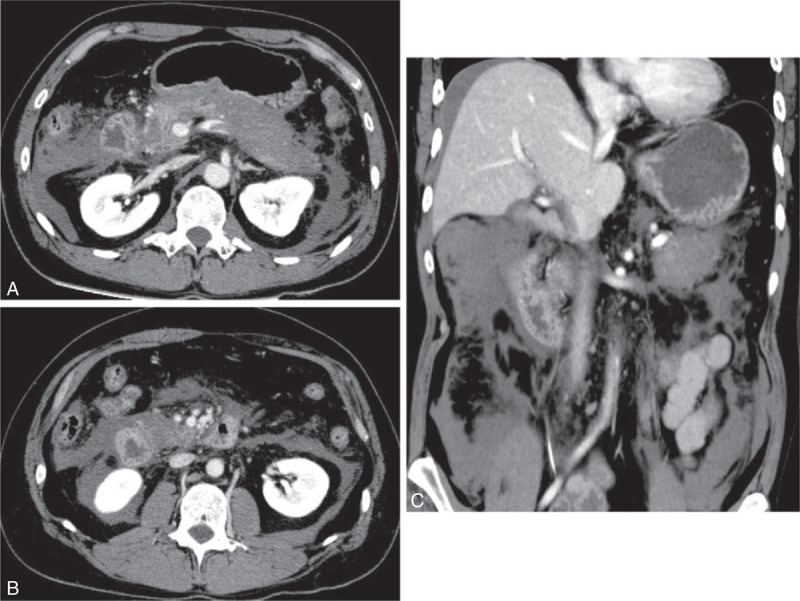

FIGURE 1.

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed enlargement of the pancreas, inflammatory changes of the peripancreatic fat, poor enhancement of the parenchyma of the pancreatic body and tail (A, B), and inflammatory changes spreading to the lower abdominal cavity (C).

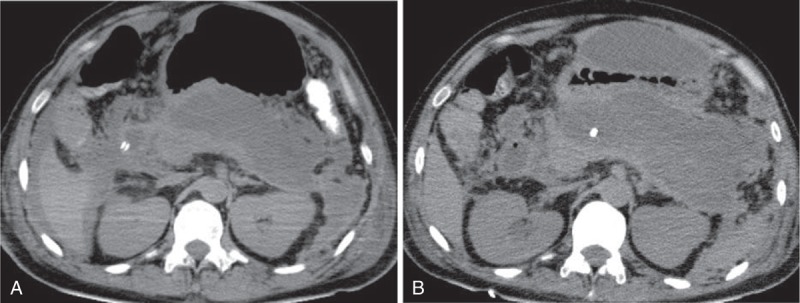

FIGURE 2.

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed a walled-off necrosis (WON) in the pancreatic body/tail and peripancreatic area 1 month after the onset of pancreatitis (A). WON had extended by 3 weeks after the onset of a cerebral infarction (4 weeks after the onset of infected WON) (B).

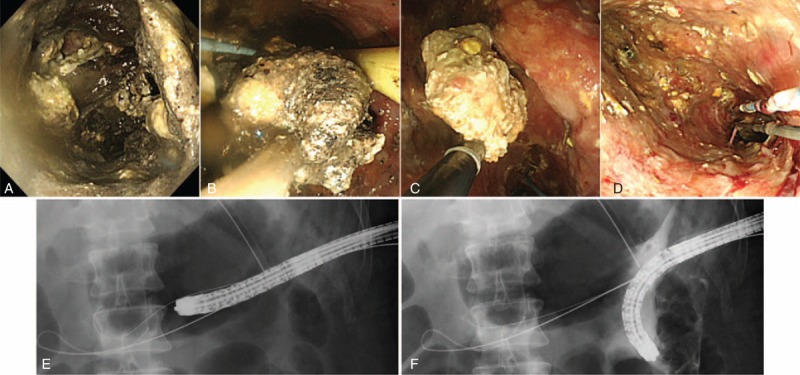

FIGURE 3.

A significant amount of necrotic tissue had accumulated in the walled-off necrosis (WON) (A). Endoscopic necrosectomy was performed via the percutaneous fistula (B, C, E, F), and as much necrotic tissue as possible was removed on 3 separate occasions (D).

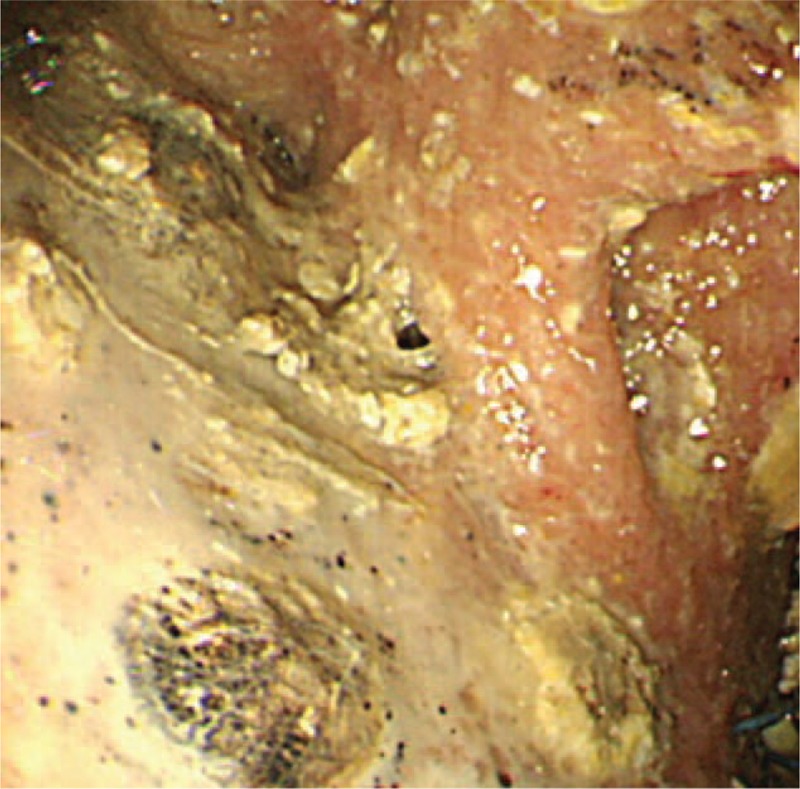

FIGURE 4.

Necrosectomy revealed a fungal nest that remained adhered to the wall of the walled-off necrosis (WON).

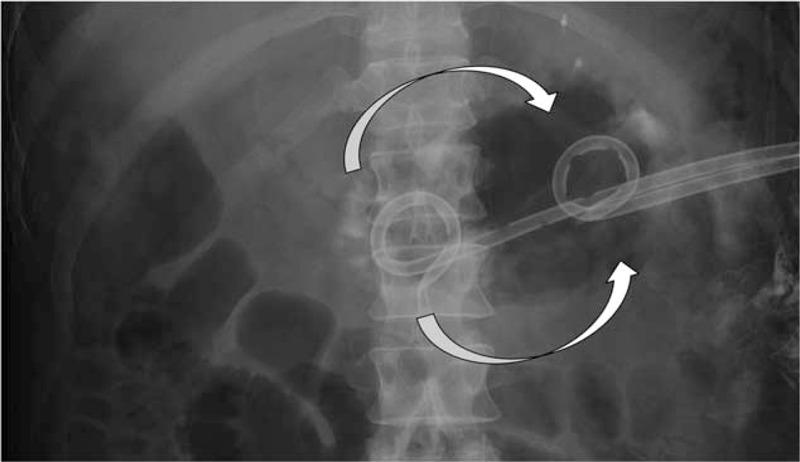

FIGURE 5.

Local administration of amphotericin B and saline with perfusion lavage of the walled-off necrosis (WON) using 2 drainage catheters: administration into WON by the pancreatic head-side catheter and discharge from the pancreatic tail-side catheters (arrow).

FIGURE 6.

Improvement in the walled-off necrosis (WON) on computed tomography (CT) after the drainage catheters had been removed.

DISCUSSION

Severe cases of infected WON have been reported to deteriorate because of poor control of the infection. When this occurs, urgent intervention by drainage and necrosectomy is indicated. Catheter drainage is the recommended first-line intervention because it can successfully treat approximately half of WON cases.5 This should then be followed by necrosectomy if necessary because this is considered superior to initial open necrosectomy.6 However, if infection control is poor with drainage alone because of the clogging of catheters by necrotic tissue, open necrosectomy is required. To avoid the high mortality associated with the open procedure, minimally invasive endoscopic necrosectomy has been reported.4,7,8 In general, endoscopic necrosectomy is performed via the gastrointestinal tract; however, the percutaneous route can be used when WON is not located adjacent to the gastrointestinal tract.9,10 In the present case, although WON was adjacent to the stomach wall, we were unable to perform endoscopic treatment because of the patient's poor condition during the initial drainage. Therefore, we initially performed percutaneous drainage with US guidance before performing endoscopic necrosectomy via the percutaneous fistula.

Recently, despite a continued mortality rate of approximately 10%, the outcomes of infected WON have improved.4,7,8 Even if necrosectomy is performed, there are severe cases in which infection control is difficult to achieve. Most infections in WONs are caused by bacteria, and fungal infection is both very rare and difficult to treat.11 An immunocompromised condition and the administration of long-term broad-spectrum antibiotics are factors that predispose a patient to fungal infection. In the present case, the initial bacterial infection was replaced by Candida infection over the course of several weeks of conservative therapy for severe cerebral infarction, during which broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy was continued.

In the present case, percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy was performed 3 times without improving the patient's condition. Adding local administration of amphotericin B and saline perfusion lavage was successful in treating the fungal infection, which is consistent with a report on the treatment of prosthetic joint infection.12 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of WON treated via local administration of amphotericin B. We believe that this approach was effective because the intravenous drugs were unable to reach WON as a result of necrosis and the necrotic tissue may have prevented the drug from acting. If amphotericin B was proven to be ineffective, we considered changing caspofungin to a drug with greater tissue transitivity. However, local administration of amphotericin B and saline perfusion lavage were performed after the removal of necrotic tissue by endoscopic necrosectomy, and this probably facilitated antifungal spread and prevented catheters from clogging. We believe that local administration of amphotericin B may be ineffective if used in isolation when a significant amount of necrotic tissue remains in WON. Further investigation will be necessary to confirm this theory.

In conclusion, the combination of endoscopic necrosectomy with local administration of amphotericin B may be effective in treating refractory fungal-infected WON by removing necrotic tissue and treating the infection directly.

Footnotes

Abbreviation: WON = walled-off necrosis.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis 2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut 2013; 62:102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Werner J, Feuerbach S, Uhl W, et al. Management of acute pancreatitis: from surgery to interventional intensive care. Gut 2005; 54:426–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison S, Kakade M, Varadarajula S, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing debridement of pancreatic necrosis. J Gastrointest Surg 2010; 14:245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seifert H, Biermer M, Schmitt W, et al. Transluminal endoscopic necrosectomy after acute pancreatitis: a multicenter study with long-term follow-up (the GEPARD Study). Gut 2009; 58:1260–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Santvoort HC, Bakker OJ, Bollen TL, et al. A conservative and minimally invasive approach to necrotizing pancreatitis improves outcome. Gastroenterology 2011; 141:1254–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, et al. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1491–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner TB, Coelho-Prabhu N, Gordon SR, et al. Direct endoscopic necrosectomy for the treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis: results from a multicenter U.S series. Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 73:718–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasuda I, Nakashima M, Iwai T, et al. Japanese multicenter experience of endoscopic necrosectomy for infected walled-off pancreatic necrosis: the JENIPaN study. Endoscopy 2013; 45:627–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto N, Isayama H, Takahara N, et al. Percutaneous direct-endoscopic necrosectomy for walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Endoscopy 2013; 45:E44–E45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navarrete C, Castillo C, Caracci M, et al. Wide percutaneous access to pancreatic necrosis with self-expandable stent: new application (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 73:609–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.2004; Zulfikaroglu B, Koc M, Ozalp N. Candida albicans-infected pancreatic pseudocyst: report of a case. 34:466–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu ES, Thompson GR, Kreulen C, et al. Amphotericin B-Impregnated bone cement to treat refractory coccidioidal osteomyelitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57:6341–6343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]