Abstract

To determine plasma concentrations of angiopoietin (Ang)-1, Ang-2, Tie-2, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in patients with sepsis-induced multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) and determine their association with mortality.

The study prospectively recruited 96 consecutive patients with severe sepsis in a l intensive care unit of a tertiary hospital. Plasma Ang-1, Ang-2, Tie-2, and VEGF levels and MODS were determined in patients on days 1, 3, and 7 of sepsis. Univariate and Cox proportional hazards analysis were performed to develop a prognostic model.

Days 1, 3, and 7 plasma Ang-1 concentrations were persistently decreased in MODS patients than in non-MODS patients (day1: 4.0 ± 0.5 vs 8.0 ± 0.5 ng/mL, P < 0.0001; day 3, 3.2 ± 0.6 vs 7.3 ± 0.5 ng/mL, P < 0.0001, day 7, 2.8 ± 0.6 vs 10.4 ± 0.7 ng/mL, P < 0.0001). In patients with resolved MODS on day 7 of sepsis, Ang-1 levels were increased from day 1 (4.7 ± 0.6 ng/mL vs 9.1 ± 1.4 ng/mL, n = 43, P = 0.004). Plasma Ang-1 levels were lower in nonsurvivors than in survivors on days 1 (4.0 ± 0.5 vs 7.1 ± 0.5 ng/mL, P < 0.0001), 3 (3.8 ± 0.6 vs 7.1 ± 0.5 ng/mL, P < 0.0001), and 7 (4.7 ± 0.7 vs 11.0 ± 0.8 ng/mL, P < 0.0001) of severe sepsis. In contrast, plasma Ang-2 levels were higher in nonsurvivors than in survivors only on day 1 (15.8 ± 2.0 vs 9.5 ± 1.2 ng/mL, P = 0.035). VEGF and Tie-2 levels were not associated with MODS and mortality. Ang-1 level less than the median value was the only independent predictor of mortality (hazard ratio, 2.57; 95% CI 1.12–5.90, P = 0.025).

Persistently decreased Ang-1 levels are associated with MODS and subsequently, mortality in patients with sepsis.

INTRODUCTION

Emerging evidences disclose that endothelial activation and injury are involved in the development of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) during sepsis. In addition to its function as vascular barrier, endothelial cells are implicated in inflammatory responses and coagulation imbalance in sepsis.1 A study showed that endothelial injury is an independent predictor for MODS and mortality in patients with severe sepsis. The degree of endothelial injury correlates with the numbers of organ failure in those patients.2 Taken together, sepsis-induced endothelial injury plays a critical role in mediating illness progression and outcome.

The angiopoietin (Ang) family contains 3 members in humans, including Ang-1, Ang-2, and Ang-4.3,4 Both Ang-1 and Ang-2 bind to the same site of Tie2 receptor with similar affinity.5 After binding to Tie-2 receptor, Ang-1 causes activation of Tie-2. In contrast, Ang-2 exerts antagonistic response to Tie-2.6 Ang-1 inhibits the endothelial response to inflammatory cytokines and exerts protective effects. In addition, Ang-1 inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-induced blood-vessel formation and adhesion molecule expression, and attenuates increased VEGF and thrombin-induced permeability.7,8 However, Ang-2 triggers inflammatory responses by activating the endothelial cell and increasing permeability.9,10

Because of the important role of Angs in endothelial activation and vascular barrier breakdown, many studies have explored their role as biomarkers of sepsis.11–13 Evidence has consistently shown increased Ang-2 levels in patients with sepsis compared with those without. But discrepancy exists in the levels of Ang-1 in patients with sepsis. Previous reports demonstrate that circulating Ang-1 levels remain unchanged, or even decrease, in septic patients.11–13 Although decreased Ang-1 levels have recently been reported as an independent predictor for mortality in pediatric patients with severe bacterial infection,13 few comprehensive clinical investigations have examined the role of circulating Ang-1 during the clinical course from MODS to subsequent mortality in sepsis. Whether longitudinally measured Ang-1 levels correlate with the resolution or aggravation of MODS during sepsis remains unclear.

The study aimed to measure plasma concentrations of Ang-1, Ang-2, Tie-2, and VEGF in patients with sepsis-induced organ failure and examine the independent association between these markers and mortality. These markers were also serially measured to determine their correlation with evolutional change of MODS status during the course of severe sepsis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This study was conducted from October 2008 to April 2010 in a 37-bed medical intensive care unit (MICU) of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, a tertiary medical center. Ninety-six patients (46 males and 50 females) were recruited within 24 hours of diagnosis of severe sepsis. Sepsis was defined as the presence of infection and at least 2 of the following criteria.14 of the American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Medicine Consensus Committee: temperature >38°C or <36°C, heart rate >90 beats/minute, respiratory rate >20 breaths/minute, PaCO2 < 32 mmHg, white blood cell >12,000/mm3 or <4000/mm3 or >10% immature (band) forms. Patients’ baseline data included age, vital signs, blood gas analysis, organ failure count, and hematologic and biochemical tests. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) scores and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score15 were used to assess illness severity. Underlying medical history was also collected, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, neurologic disease, congestive heart failure, malignancy, and chronic airway obstruction disease.

The hospital's Institutional Review Board approved the study and all patients or their legal representatives provided written informed consent. The patients were treated according to the Surviving Sepsis Guidelines.16

Definitions

Organ failure was diagnosed according to the ACCP-SCCM Consensus Committee criteria.14 Respiratory failure was defined as needing mechanical ventilation. Cardiovascular failure was defined as systolic BP ≤ 90 mmHg or mean arterial pressure ≤ 60 mmHg for 1 hour, despite fluid bolus. Renal failure was defined as low urine output (eg, <0.5 mL/kg/hour), increased creatinine (≥50% increase from baseline), or the need for acute dialysis. Hematologic failure was defined as low platelet count (<100,000/mm3) or PT/PTT > upper limits of normal. Metabolic failure was low pH with high lactate (eg, pH < 7.30 and plasma lactate > upper limits of normal), while hepatic failure was liver enzyme levels >2× the upper limits of normal. CNS failure was defined as altered consciousness or reduced Glasgow Coma Score. Those with more than 2 organ dysfunctions were defined as MODS.2,14 Day 1 was the day the patients were recruited.

The number of organ failure was determined on days 1, 3, and 7 of sepsis in each patient. Patients with persistently MODS on days 1 and 7 were defined as having persistent MODS. The no MODS group was defined as having organ failure counts less than 3 on days 1 and 7. Patients with MODS on day 1 but with organ failure number less than 3 on day 7 were defined as resolved MODS.

Blood Sampling and Measurement

Blood samples were taken on days 1, 3, and 7 of sepsis for plasma collection. The maximum levels of laboratory data were used for determination of organ function and comparison between survivors and nonsurvivors. Soluble Ang-1, Ang-2, VEGF, and Tie-2 plasma concentrations (Sekisui Diagnostics, MA) on days 1, 3, and 7 were determined by ELISA based on the manufacturer's instructions. Plasma levels of these mediators were compared between patients with and without MODS, and between survivors and nonsurvivors. For sequential MODS changes, patients were classified into 3 groups (ie, no MODS, resolved MODS, and persistent MODS) and compared.

Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SEM or percentage. Since most continuous variables were skewed, nonparametric approaches were used. Quantitative variables between 2 groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney test for continuous and ordinal variables, and the chi-square test for nominal variables. Nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon signed rank) were used for comparison of time points within a group. Differences among comparison for more than 2 groups were determined using the Kruskal–Wallis test. The primary outcome studied was in-hospital mortality.

Univariate analyses were primarily used for the selection of variables, based on P value less than 0.1. Selected variables, including APACHE II score, SOFA score, Ang-1 levels, Ang-2 levels, C-reactive protein (CRP), and lactate were entered into a Cox proportional hazards model to identify the net effects of each individual factor. Hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to assess independent contributions of significant factors. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for day 1 APACHE II scores, plasma levels of Ang-1, Ang-2, CRP, and lactate for predicting the development of MODS and mortality during ICU stay were plotted, and the respective areas under the curves were calculated. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analysis was done using the SPSS software version 10.0 (Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

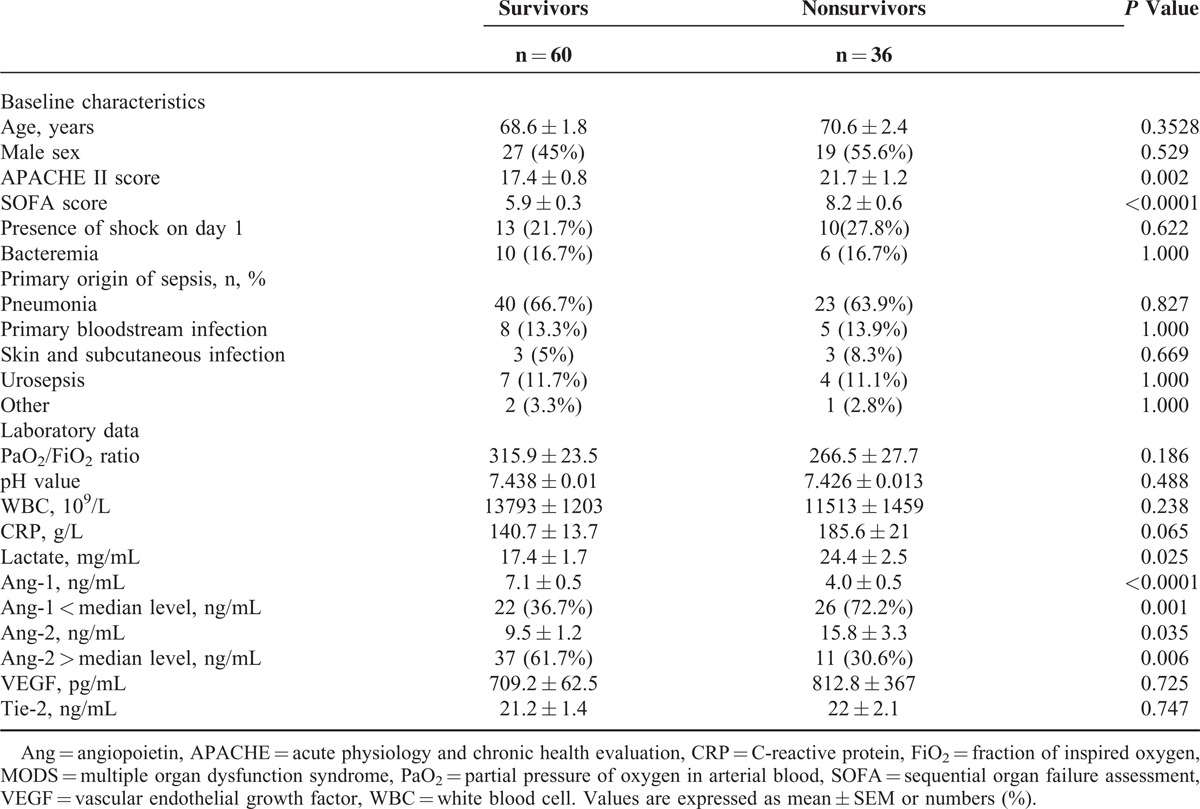

The 96 patients enrolled were classified as survivors and nonsurvivors during their hospital stay. Their baseline characteristics were listed in (Table 1). Thirty-six (37.5%) died during their hospitalization. There were no differences between survivors and nonsurvivors in age, sex, shock, bacteremia, and origin of sepsis. However, the nonsurvivors had higher illness severity than survivors, as indicated by APACHE II score (21.7 ± 1.2 vs 17.4 ± 0.8, P = 0.002). The SOFA scores of nonsurvivors differed from those of survivors on day 1 (8.2 ± 0.6 vs 5.9 ± 0.3, P < 0.0001). They also had higher levels of lactate (24.4 ± 2.5 vs 17.4 ± 1.7 mg/dL, P = 0.025) and Ang-2 (15.8 ± 3.3 vs 9.5 ± 1.2 ng/mL, P = 0.035) but lower Ang-1 levels (4.0 ± 0.5 vs 7.1 ± 0.5 ng/mL, P < 0.0001) than survivors.

TABLE 1.

Factors Associated With Mortality in Patients With Severe Sepsis

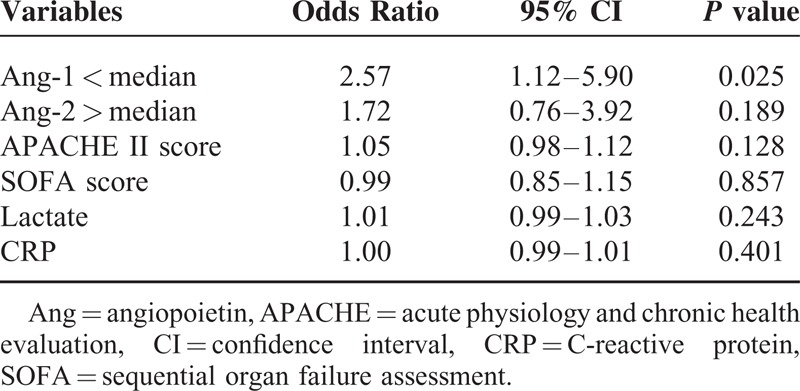

Cox Proportional Hazard Analysis for Predicting Mortality

The APACHE II and SOFA scores and CRP, lactate, and Ang-1 levels less than the median value (<5.5 ng/mL) and Ang-2 level higher than the media value (>7.0 ng/mL) were subjected to Cox proportional hazard analysis (Table 2). Except for Ang-1 level (HR, 2.57; 95% CI 1.12–5.90, P = 0.025), all other variables did not remain significant in the Cox proportional hazard analysis. Therefore, Ang-1 levels less than the median value were the only independent predictor for mortality in patients with severe sepsis.

TABLE 2.

Major Factors Associated With Mortality in Patients With Severe Sepsis, by Cox Proportional Hazard Analysis

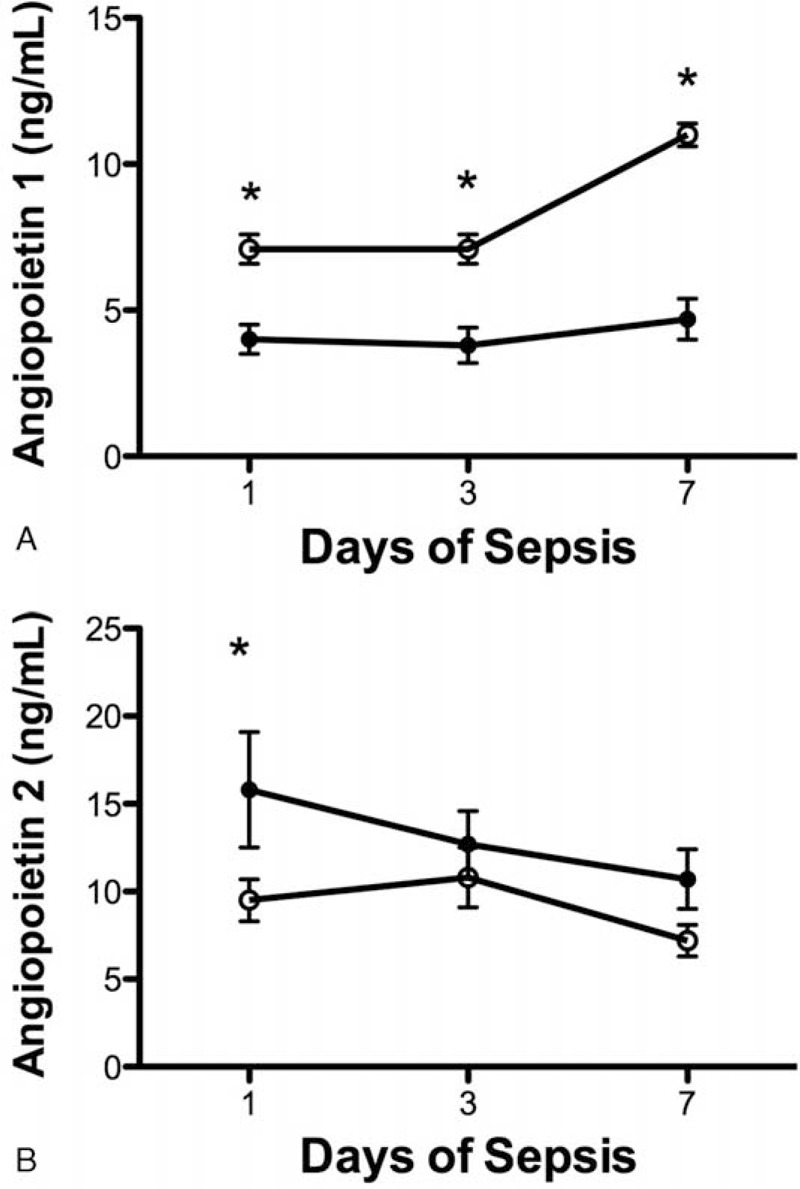

Plasma Levels of Angiopoietins and Clinical Outcomes

The plasma levels of Ang-1 were lower in nonsurvivors than in survivors on days 1 (4.0 ± 0.5 vs 7.1 ± 0.5 ng/mL, P < 0.0001), 3 (3.8 ± 0.6 vs 7.1 ± 0.5 ng/mL, P < 0.0001), and 7 (4.7 ± 0.7 vs 11.0 ± 0.8 ng/mL, P < 0.0001) (Figure 1A). In contrast, plasma Ang-2 levels were higher in nonsurvivors than in survivors only on day 1 (15.8 ± 2.0 vs 9.5 ± 1.2 ng/mL, P = 0.035) but not on day 3 (12.7 ± 1.9 vs 10.8 ± 1.7 ng/mL, P = 0.474) and day 7 (10.7 ± 1.7 vs 7.2 ± 1.0 ng/mL, P = 0.060) (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Relationship between serial angiopoietin (Ang) plasma levels and mortality. (A) Serial mean Ang-1 plasma levels were significantly lower in nonsurvivors (filled circle) than in survivors (open circle) of severe sepsis on days 1, 3, and 7 (P < 0.0001). (B) Plasma levels of Ang-2 were higher in nonsurvivors than in survivors only on day 1 (P = 0.035) but not on days 3 and 7 of severe sepsis. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM.

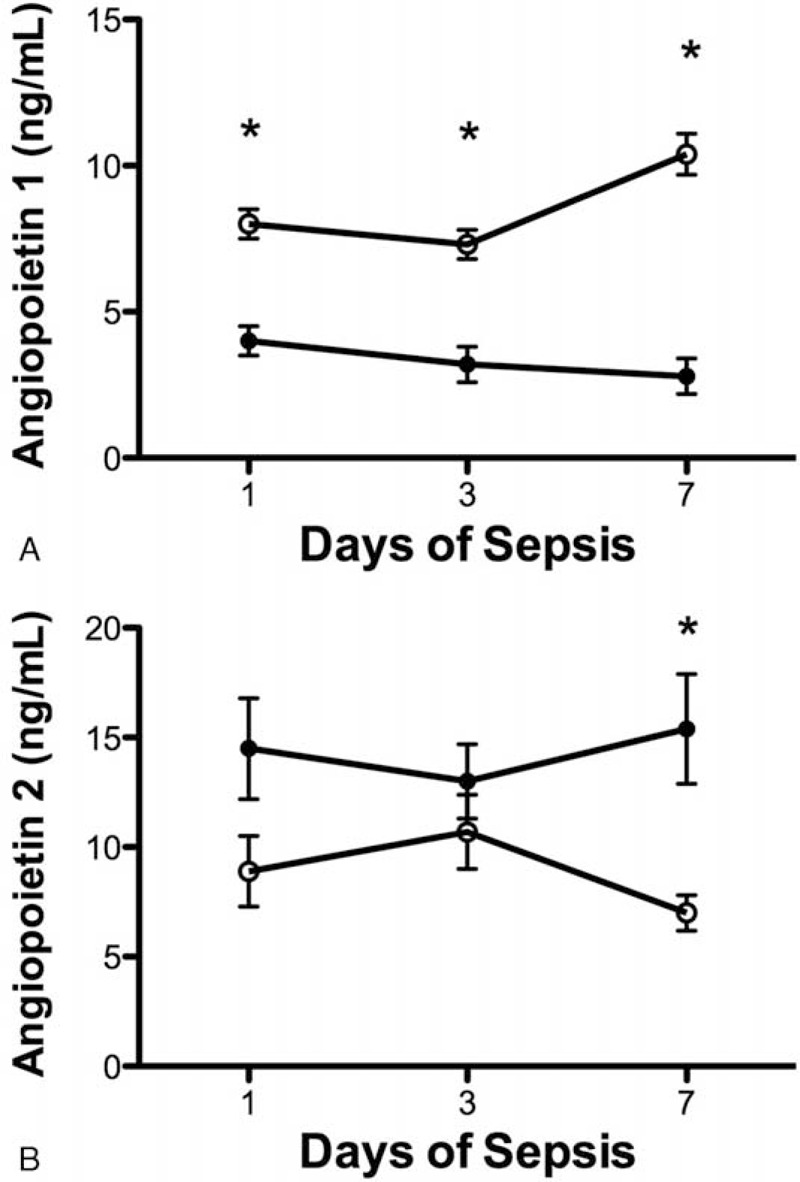

Similarly, plasma Ang-1 levels were lower in MODS patients than in those without MODS on days 1 (4.0 ± 0.5 [n = 50] vs 8.0 ± 0.5 [n = 46] ng/mL, P < 0.0001), 3 (3.2 ± 0.6 [n = 34] vs 7.3 ± 0.5 [n = 62] ng/mL, P < 0.0001), and 7 (2.8 ± 0.6 [n = 19] vs 10.4 ± 0.7 [n = 72] ng/mL, P < 0.0001) (Figure 2A). However, plasma levels of Ang-2 were higher in MODS patients than in non-MODS patients on day 7 (15.4 ± 2.5 vs 7.0 ± 0.8 ng/mL, P < 0.0001) but not on day 1 (14.5 ± 2.3 vs 8.9 ± 1.6 ng/mL, P = 0.053) and day 3 (13.0 ± 1.7 vs 10.6 ± 1.7 ng/mL, P = 0.399) (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Relationship between serial angiopoietin (Ang) plasma levels and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). (A) Serial mean Ang-1 plasma levels were significantly lower in patients with MODS (filled circle) than those without (open circle) on days 1, 3, and 7 (P < 0.0001) of severe sepsis. (B) Plasma levels of Ang-2 were higher in patients with MODS than those without only on day 7 (P = 0.035) but not on days 1 and 3 of severe sepsis. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM.

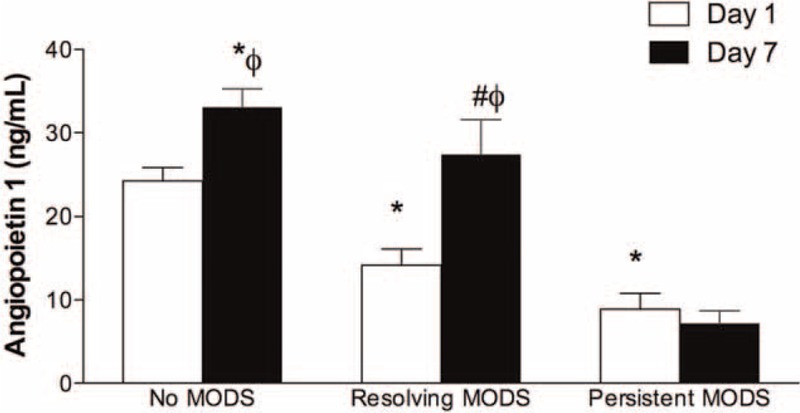

Plasma Ang-1 concentrations in septic patients stratified by MODS status were compared (Figure 3). Plasma Ang-1 concentrations were lower in patients with persistent MODS (n = 17) (3.0 ± 0.6 ng/mL on day 1 and 2.4 ± 0.5 ng/mL on day 7) than in patients with no MODS (n = 29) (day 1, 8.1 ± 0.5 ng/mL, P < 0.0001 and day 7, 11.0 ± 0.7 ng/mL, P < 0.0001). However, in patients with resolved MODS (n = 43), the Ang-1 levels increased from day 1 to day 7 (4.7 ± 0.6 ng/mL vs 9.1 ± 1.4 ng/mL, P = 0.004). Plasma Ang-1 levels in patients with resolving MODS were similar to those of patients with no MODS on day 7 (P = 0.188). Patients with persistent MODS also had persistently low levels of Ang-1 on days 1 and 7 (P = 0.482). In patients with no MODS, plasma Ang-1 level mildly increased from day 1 to day 7 (P = 0.016). Plasma Ang-1 levels in patients with resolving MODS were similar to those of patients with persistent MODS on day 1 (P = 0.07).

FIGURE 3.

Concentrations of angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) in patients with no, resolved, or persistent multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) from day 1 to day 7. Open bars, concentrations of Ang-1 on day 1; solid bars, concentrations of Ang-1 on day 7; ∗P < 0.05 compared to day 1 no MODS group; #P < 0.05 compared to day 7 no MODS group; ϕP < 0.05 compared to day 1 levels in the same group. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM.

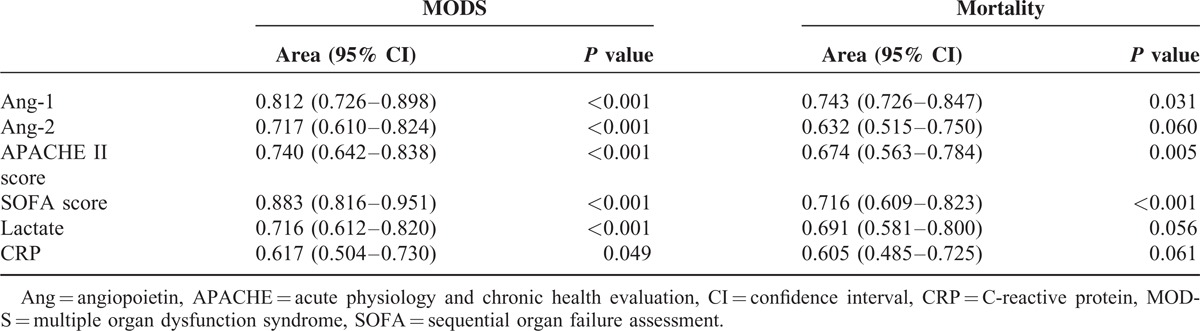

Area Under the ROC Curve for Day 1 Soluble Factor Levels, SOFA Score and APACHE II Scores in Predicting Outcomes

Areas under the ROC curve for plasma Ang-1, Ang-2, CRP, and lactate levels, and SOFA and APACHE II scores on day 1 were compared for predicting clinical outcomes (Table 3). Values for areas under the ROC curves showed that day 1 plasma Ang-1 levels had good discriminative power in predicting MODS (0.743) and mortality (0.898). In addition, APACHE II score also had good discriminative power for MODS (0.674) and mortality (0.740). The areas under the ROC curve for day 1 plasma Ang-2 (0.717), CRP (0.617), and lactate (0.716) levels and SOFA scores (0.883) were adequate only in predicting mortality but not MODS.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of Areas Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curves for Variables on Day 1 of Severe Sepsis (n = 96)

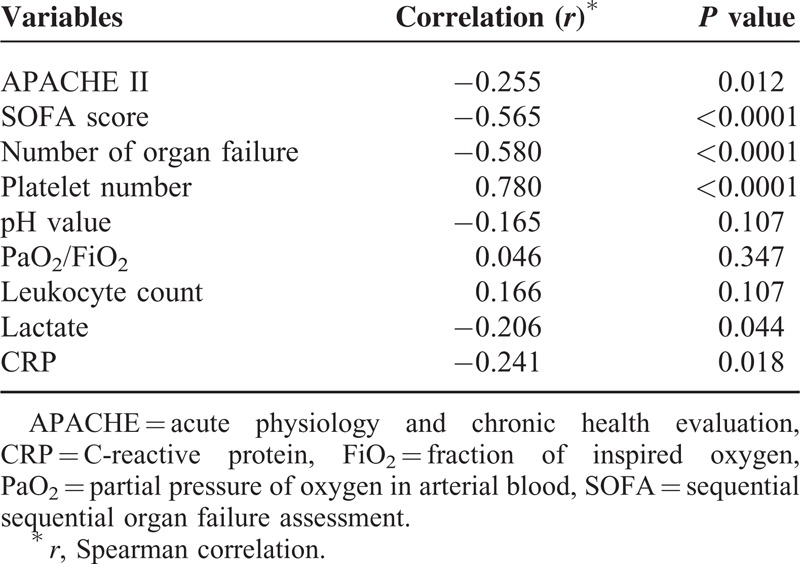

Plasma Ang-1 and Organ Dysfunction and Illness Severity

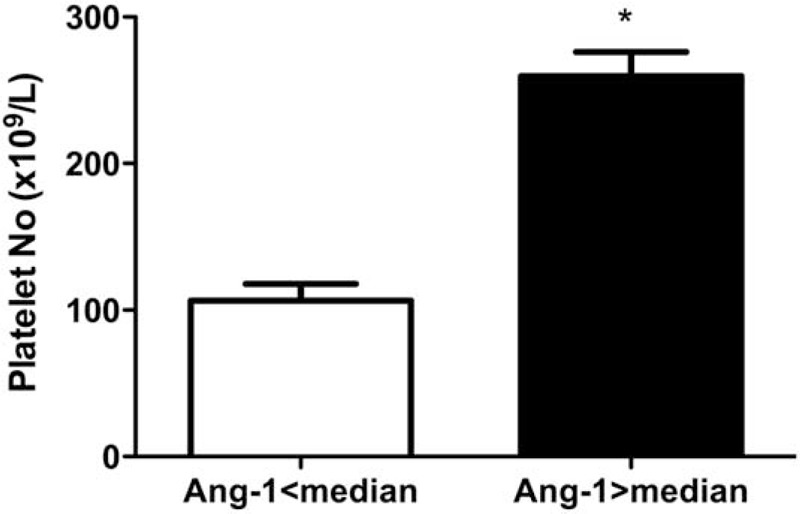

To further understand the relationship between Ang-1 and organ dysfunction, Ang-1 levels were compared to several variables of illness severity and laboratory findings associated with organ dysfunction (Table 4). Ang-1 negatively correlated with APACHE II (r = −0.255, P = 0.012) and SOFA scores (r = −0.565, P < 0.0001), number of organs affected by failure (r = −0.580, P < 0.0001), and serum CRP (r = −0.241, P = 0.018) and lactate (r = −0.206, P = 0.044) levels. In contrast, the plasma Ang-1 levels positively correlated with platelet count (r = 0.780, P < 0.0001) such that the platelet count of patients with plasma Ang-1 higher than the median level (n = 48) (259.6 ± 16.5 1000/mm3) was higher than those with Ang-1 level lower than the median value (n = 48) (106.4 ± 11.4 1000/mm3, P < 0.0001) (Figure 4).

TABLE 4.

Bivariate Correlation Between Angiopooietin-1 and Clinical and Biologic Variables in Patients With Sepsis

FIGURE 4.

The platelet number in patients with plasma angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) concentrations lower and higher than the median value. Open bars, patients with plasma Ang-1 concentrations lower than the median value; solid bars, patients with plasma Ang-1 concentrations higher than the median value; ∗P < 0.05 compared to patients with plasma Ang-1 concentrations lower than the median value. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM.

DISCUSSION

This study reveals that plasma Ang-1 levels changes and are decreased with the evolution of MODS in patients with severe sepsis. Concentrations of Ang-1 increase in patients with resolved MODS but remain low in patients with persistent MODS. Moreover, Ang-1 levels on day 1 of sepsis independently predict mortality during hospital stay. Analysis of area under the ROC curve confirms that day 1 plasma Ang-1 levels have good discriminative power for predicting MODS and mortality, and decreased Ang-1 levels are associated with decreased platelet count in patients with severe sepsis.

In the current study, the APACHE II and SOFA scores, and CRP, lactate, Ang-1, and Ang-2 levels are different between survivors and nonsurvivors, even though Ang-1 level is the only independent predictor for mortality after Cox proportional analysis. The functions of Ang-1 are to maintain vessel integrity, inhibit vascular leakage, suppress inflammatory gene expression, and prevent recruitment and transmigration of leukocytes.17 The inadequate amount of Ang-1 in septic patients contributes to uncontrolled inflammation, injury of endothelial cells, and increased vascular permeability.17 In fact, endothelial injury2 and increased vascular permeability18,19 have been documented as possible mechanisms underlying sepsis-induced organ failure and mortality. The failure to maintain quiescence status of endothelial cells due to inadequate Ang-1 during sepsis may play an important role in the development of organ failure and followed by mortality. Consistent with previous studies, this study demonstrates that day 1 plasma Ang-1 and Ang-2 levels are significantly different between nonsurvivors and survivors among patients with severe sepsis. Only Ang-1 level remains significant after multivariate analysis.11,13 Nonetheless, other studies have not consistently shown a correlation between Ang-1 levels and mortality. A previous study showed that plasma Ang-1 levels were similar between surgical patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and those without.20 Similarly, another study also failed to demonstrate a difference in plasma Ang-1 levels between survivors and nonsurvivors among mechanically ventilated patients with septic shock.11 Discrepancies in the observed association between low Ang-1 levels and MODS and mortality in severe sepsis in the present study and in previous ones may relate to the difference in study populations and illness severity. In contrast to previous studies recruiting surgical patients complicated with ARDS or mechanically ventilated patients with septic shock, the present study recruited patients with sepsis complicated by organ dysfunction in an MICU. Less than 30% of the patients had septic shock in this study.

This study also demonstrates that persistently depressed plasma Ang-1 level is associated with MODS and subsequent death in patients with severe sepsis. The present study reveals that Ang-1 levels are repressed in patients with MODS and increase with MODS resolution. The values for areas under the ROC curve also show that plasma Ang-1 level on day 1 of sepsis has good discriminative power for predicting both MODS and mortality outcomes. These findings suggest that plasma Ang-1 level may serve as an early predictor of survival in septic patients. By serial measurement of Ang-1 levels, the persistent depressed Ang-1 levels may be used to identify the patients with persistent MODS and are vulnerable to mortality. In contrast, increased plasma Ang-1 on day 7 may indicate patients with resolved MODS. Our study results, if further confirmed by large-scale prospective studies, provided a useful marker to stratify the patients by measuring plasma Ang-1 levels. Therefore, serial measuring plasma Ang-1 in patients with severe sepsis should prompt efforts to identify and treat the modifiable factors associated with mortality. In patients with persistently decreased Ang-1 levels, some interventions may be instituted to improve survival. According to the Surviving Sepsis Guidelines,16 those interventions include: further studies performed promptly for confirming potential source of infection, reassessment of antibiotic therapy with microbiology and clinical data, a low tidal volume and limitation of inspiratory plateau pressure strategy for acute lung injury (ALI)/ARDS, and maintain tissue perfusion by targeting a hemoglobin of 7 to 9 g/dL. However, further studies are warranted to confirm the application of plasma Ang-1 monitoring on the management of patients with severe sepsis.

Plasma Ang-1 levels negatively correlated well with organ failure status indicated by SOFA score and organ failure counts (Table 4). These findings further support the theory that inadequate amount of Ang-1 has a pathogenic role in sepsis and contributes to organ dysfunction, likely through endothelial activation and subsequent vascular leak, which could result in circulatory, hepatic, and renal compromise. These results are in agreement with previous clinical study reporting that plasma levels of Ang-1 are associated with organ failure in sepsis.21 Indeed, an animal study had disclosed that administration of Ang-1 significantly protects against sepsis-associated organ dysfunctions and improves survival time, most likely by preserving endothelial barrier function.22 Recently, platelets have been identified as carriers of angiogenic factors since a high amount of Ang-1 is found in platelets.23,24 Results here demonstrate a positive correlation between Ang-1 level and platelet count. Moreover, the platelet counts of patients with plasma Ang-1 >median level is higher than those with Ang-1 level <median value. These findings suggest that sepsis-induced thrombocytopenia may contribute to the depressed levels of Ang-1 in patients with severe sepsis. Thrombocytopenia is typically a result of sepsis and mainly caused by sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).2 The presence of DIC is closely linked to sepsis-induced MODS and higher mortality rates.25,26 The thrombocytopenia-associated depressed Ang-1 levels may play a certain role in the progression from sepsis-induced DIC to MODS and subsequent death.

Our study has limitations. First, we stratified the survivors versus nonsurvivors according to the in-hospital mortality. It is possible that patients who initially recovered from the septic insult may have died from another complication of critical illness. This would have an effect to decrease the power of Ang-1 to predict mortality in those patients with cause of death other than sepsis. However, our results that persistently decreased Ang-1 correlated with MODS course and mortality in patients with severe sepsis reinforces the use of Ang-1 as a predictive biomarker. Second, our study was performed in a single center. A larger study at multiple sites should be performed to confirm these findings.

In conclusion, plasma Ang-1 levels are repressed in sepsis-induced MODS and mortality. Plasma concentrations of this marker increase concomitantly with the resolution of MODS and independently predict mortality in patients with severe sepsis. These may suggest that the inadequate amount of Ang-1 plays a critical role in progression from MODS to mortality. Thus, plasma Ang-1 levels may be used for monitoring MODS status in patients with severe sepsis, particularly day 1 plasma Ang-1 levels, which may be used as an early predictor of mortality.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank National Science Council of Taiwan and research grants from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan for funding.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: Ang = angiopoietin, APACHE II = acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II, ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome, CI = confidence interval, CRP = C-reactive protein, DIC = disseminated intravascular coagulation, HR = hazard ratios, MODS = multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, ROC = receiver operating characteristic, SOFA = sequential organ failure assessment, VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor, MICU = medical intensive care unit.

This project was supported by the National Science Council of Taiwan, R.O.C. (NSC 97-2314-B-182A-088-MY3) and research grants from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan (CMRPG 3B0822).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aird WC. The role of the endothelium in severe sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Blood 2003; 101:3765–3777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin SM, Wang YM, Lin HC, et al. Serum thrombomodulin level relates to the clinical course of disseminated intravascular coagulation, multiorgan dysfunction syndrome, and mortality in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med 2008; 36:683–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yancopoulos GD, Davis S, Gale NW, et al. Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature 2000; 407:242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones N, Iljin K, Dumont DJ, et al. Tie receptors: new modulators of angiogenic and lymphangiogenic responses. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2001; 2:257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maisonpierre PC, Suri C, Jones PF, et al. Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis. Science 1997; 277:55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiedler U, Krissl T, Koidl S, et al. Angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2 share the same binding domains in the Tie-2 receptor involving the first Ig-like loop and the epidermal growth factor-like repeats. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:1721–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asahara T, Chen D, Takahashi T, et al. Tie2 receptor ligands, angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2, modulate VEGF-induced postnatal neovascularization. Circ Res 1998; 83:233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim I, Moon SO, Park SK, et al. Angiopoietin-1 reduces VEGF-stimulated leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells by reducing ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin expression. Circ Res 2001; 89:477–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roviezzo F, Tsigkos S, Kotanidou A, et al. Angiopoietin-2 causes inflammation in vivo by promoting vascular leakage. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2005; 314:738–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemieux C, Maliba R, Favier J, et al. Angiopoietins can directly activate endothelial cells and neutrophils to promote proinflammatory responses. Blood 2005; 105:1523–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Heijden M, Pickkers P, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, et al. Circulating angiopoietin-2 levels in the course of septic shock: relation with fluid balance, pulmonary dysfunction and mortality. Intensive Care Med 2009; 35:1567–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ricciuto DR, dos Santos CC, Hawkes M, et al. Angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2 as clinically informative prognostic biomarkers of morbidity and mortality in severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2011; 39:702–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mankhambo LA, Banda DL, Jeffers G, et al. The role of angiogenic factors in predicting clinical outcome in severe bacterial infection in Malawian children. Crit Care 2010; 14:R91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med 2003; 31:1250–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 1996; 22:707–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Intensive Care Med 2008; 34:17–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Witzenbichler B, Westermann D, Knueppel S, et al. Protective role of angiopoietin-1 in endotoxic shock. Circulation 2005; 111:97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung FT, Lin SM, Lin SY, et al. Impact of extravascular lung water index on outcomes of severe sepsis patients in a medical intensive care unit. Respir Med 2008; 102:956–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung FT, Lin HC, Kuo CH, et al. Extravascular lung water correlates multiorgan dysfunction syndrome and mortality in sepsis. PloS One 2010; 5:e15265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallagher DC, Parikh SM, Balonov K, et al. Circulating angiopoietin 2 correlates with mortality in a surgical population with acute lung injury/adult respiratory distress syndrome. Shock 2008; 29:656–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukasz A, Hellpap J, Horn R, et al. Circulating angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2 in critically ill patients: development and clinical application of two new immunoassays. Crit Care 2008; 12:R94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.David S, Park JK, Meurs M, et al. Acute administration of recombinant Angiopoietin-1 ameliorates multiple-organ dysfunction syndrome and improves survival in murine sepsis. Cytokine 2011; 55:251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salgado R, Benoy I, Bogers J, et al. Platelets and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF): a morphological and functional study. Angiogenesis 2001; 4:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lukasz A, Hellpap J, Horn R, et al. Circulating angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2 in critically ill patients: development and clinical application of two new immunoassays. Crit Care 2008; 12:R94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gando S, Kameue T, Nanzaki S, et al. Participation of tissue factor and thrombin in posttraumatic systemic inflammatory syndrome. Crit Care Med 1997; 25:1820–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wada H, Wakita Y, Nakase T, et al. Outcome of disseminated intravascular coagulation in relation to the score when treatment was begun, Mie DIC Study Group. Thromb Haemost 1995; 74:848–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]