Abstract

The aim of this study was to explore the principle of moblile echogenicities in epididymis in patients with a history of postvasectomy or infertility, which were reported as the characteristic sonographic sign of filarial infection.

We reported a 38-year-old man presented with a 3-year history of infertility after marriage. Ultrasound imaging revealed an enlarged body in the inner left epididymis along with innumerable punctate mobile echogenicities, which showed random to-and-fro movements in the left epididymis. This had previously been recognized as the sonographic filarial dance sign of live filarial worms or microfilaria. The patient subsequently underwent needle aspiration of the left epididymis.

Histopathological examination confirmed that the mobile echogenicities were a large number of macrophages with phagocytized sperm or clumps of agglutinated sperm. Our report includes a video clip that will help familiarize readers with this phenomenon.

Our case highlighted that moblile echogenicities should be an important sign for epididymal obstruction to initiate corresponding treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Mobile echogenicities in the epididymis have always been described as the “filarial dance,” a characteristic sonographic appearance that was first reported in 1994.1 This filarial dance refers to the random to-and-fro movements of innumerable tiny echogenic particles in the epididymis of men infected with adult Wuchereria bancrofti worms or microfilaria. Our report also describes this phenomenon but without the filariasis infestation history. In addition, the mobile echogenicities were confirmed by a histopathological examination, and we attempt to discuss the principle.

CASE REPORT

A 38-year-old man presented with a 3-year history of infertility after marriage. He was a national public servant who came from an area nonendemic for filariasis and who denied a history of filariasis infestation. He had not had any previous scrotal surgeries and had no impression of acute or chronic manifestations in the scrotum. Clinical examination revealed a slightly swollen left scrotum. An ultrasound of the scrotum was performed with a Mylab 90 ultrasound system (Esaote, Genoa, Italy) using a LA 532 transducer with a frequency of 4–13 MHz with the body in a supine position.

The quantitative and qualitative characteristics of the organs of the male genital tract were evaluated according to the European Academy of Andrology suggestions (http://www.andrologyacademy.net/default.aspx). The transrectal ultrasound had been performed in another hospital 2 weeks ago, which suggested no distal obstruction, according to recent literature.2,3 Both testes were normal in size and echo pattern (Table 1). Innumerable punctate mobile echogenicities were detected in the enlarged body of left epididymis with dilation and inhomogenicity,4,5 while the right epididymis was normal (Figures 1 and 2). These echogenicities had a random to-and-fro motion and were no more than 1 mm in diameter and with comet tail sign. Doppler ultrasonography showed no obvious blood-flow signal in left epididymis. Static imaging as well as a video clip of the random, undulating motion were recorded (Clip 1). This was identified as the typical sonographic filarial dance sign of filarial worms, and a provisional diagnosis of scrotal filariasis was suggested. The patient subsequently underwent needle aspiration of the lesion. Microbial cultures yielded negative results, and there were neither filarial worms nor microfilaria, nor were there any other parasites in the aspirate as discerned by microscopy. The seminal plasma α-glucosidase, fluid fructose, and elastase were all below normal levels, which would suggest the obstruction of epididymis (Table 2). Wet smear result showed there were many sperm and clumps of agglutinated sperm. Histopathological examination confirmed that the mobile echogenicities were a large number of macrophages with phagocytized sperm (Figures 3–5).

TABLE 1.

Quantitative and Qualitative Characteristics of the Organs of the Male Genital Tract of the Patient

FIGURE 1.

Longitudinal US images of the body of left epididymis (arrow) and the contralateral normal epididymis (arrow head). Anterior–posterior diameter of the body of left epididymis was 5.7 mm, while the contralateral normal epididymis was 2.7 mm.

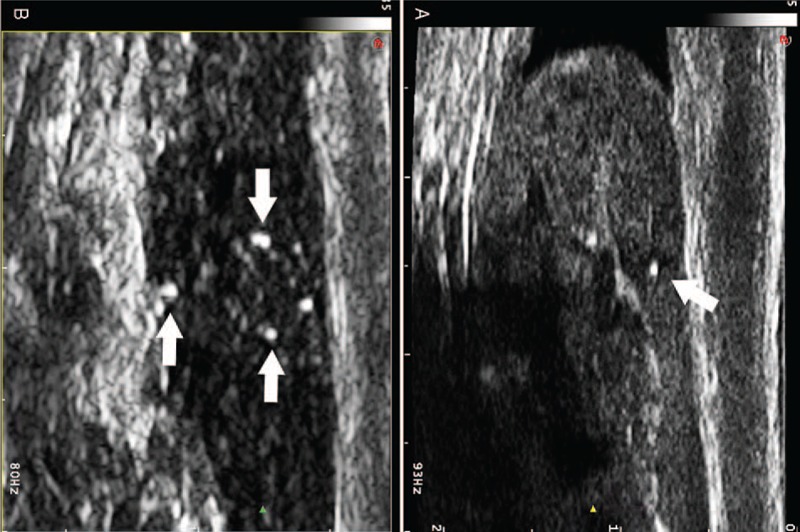

FIGURE 2.

Longitudinal US images of the head and body of the left epididymis showing a cluster of punctate echogenicities (arrows), which were not more than 1 mm in diameter and with comet tail sign.

TABLE 2.

Semen Analysis of the Patient

FIGURE 3.

Wet smear result showed that there were many clumps of agglutinated sperm (arrow).

FIGURE 5.

A, Histopathological examination showed that there were many macrophages (arrow) with CD68 (+) and MAC387 (+) in the dilated seminiferous tubules accompanied by a sperm phagocytosis phenomenon. B, The seminiferous epithelium also exhibited CD68 (+) and MAC387 (+).

This study was approved by the first affiliated hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained.

DISCUSSION

Many reports1,6–8 have described the “filarial dance” sign, which refers to the ultrasound finding of numerous tiny particles showing random to-and-fro movements within a distended epididymis thought to represent infection with filarial worms or microfilaria. Despite the findings of those previous studies, the results of our observations diverged from the existing theory that filarial dance is due to microfilaria or adult filarial worms in constant motion. We found a sonographic appearance indistinguishable from the well-described filarial dance in a male patient who had no history of infection or travel to a filarial-endemic area. To the best of our knowledge, this phenomenon in patients lacking histories of filariasis infestation had only been described in 2 reports.9,10 However, neither of these studies obtained pathological results.

Adejolu et al10 found that 77.8% of the men (14/18) had evidence of previous vasectomy with the epididymis, but Frates et al's9 results showed that only 12.5% (7/56) of such patients had postvasectomy histories. Despite the considerable difference between those 2 results, all of the patients, including that in our case, had one thing in common: an obstructed epididymis. Thus, we posited that this phenomenon was an important sign for epididymal obstruction, which might be caused not only by filarial infection or postvasectomy factors but also by chronic orchiepididymitis, which were consistent with previous reports.2

The 2 reports suggest that the moving echogenic particles represent clumps of agglutinated sperm within dilated ducts and that the underlying etiology for the appearance of random movement was due to acoustic streaming.11 (A single spermatozoa, measuring approximately not more than 55 μm, would only be visible microscopically.) This hypothesis was confirmed by our results, in which many clumps of agglutinated sperm were detected in a wet smear (Figure 3).

Histopathological examination showed that there were many giant cells in the dilated seminiferous tubules to the exclusion of a large number of sperm (Figure 4). Immunohistochemistry confirmed that the giant cells were macrophages with CD68(+) and MAC387(+) (Figure 5), and it showed different degrees of the phenomenon of sperm phagocytosis. Moreover, CD68(+) and MAC387(+) were also detected in the seminiferous epithelium, so we speculated that the macrophages in the dilated seminiferous tubules might have originated from seminiferous epithelium stem cells with prolonged obstruction time of the epididymis. The diameter of the largest giant cell was approximately 100 μm, and this would be visible on sonographic imaging. So, another possibility was that the mobile echogenicities in the epididymis might be a large number of macrophages with phagocytized sperm.

FIGURE 4.

Histopathological examination showed that there were many giant cells (arrow head) in the dilated seminiferous tubules to the exclusion of a large number of sperm (arrow).

In conclusion, we have described and confirmed a sonographic appearance identical to the filarial dance in men with no histories of filarial infection; we believe that this finding may occur in men with an obstructed epididymis.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge funding from the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No: 30901384 and No: 81271576), the Guangdong Province Medical Research Foundation (No: A2013194), and the Guangdong Province S&T Plan Foundation (No: 2013B060500044).

Footnotes

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

Video 1. Many isolated, tiny mobile echogenicities within a dilated epididymis with random movement on sonographic imaging.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amaral F, Dreyer G, Figueredo-Silva J, et al. Live adult worms detected by ultrasonography in human Bancroftian filariasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1994; 50:753–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lotti F, Maggi M. Ultrasound of the male genital tract in relation to male reproductive health. Hum Reprod Update 2015; 21:56–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lotti F, Corona G, Colpi GM, et al. Seminal vesicles ultrasound features in a cohort of infertility patients. Hum Reprod 2012; 27:974–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lotti F, Maggi M. Interleukin 8 and the male genital tract. J Reprod Immunol 2013; 100:54–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lotti F, Corona G, Mancini M, et al. Ultrasonographic and clinical correlates of seminal plasma interleukin-8 levels in patients attending an andrology clinic for infertility. Int J Androl 2011; 34 (6 Pt 1):600–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chew LL, Teh HS. The filarial dance sign in scrotal filarial infection: a case report. J Clin Ultrasound 2013; 41:377–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mand S, Marfo-Debrekyei Y, Dittrich M, et al. Animated documentation of the filaria dance sign (FDS) in bancroftian filariasis. Filaria J 2003; 2:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaubal NG, Pradhan GM, Chaubal JN, et al. Dance of live adult filarial worms is a reliable sign of scrotal filarial infection. J Ultrasound Med 2003; 22:765–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frates MC, Benson CB, Stober SL. Mobile echogenicities on scrotal sonography: is the finding associated with vasectomy. J Ultrasound Med 2011; 30:1387–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adejolu M, Sidhu PS. The “filarial dance” is not characteristic of filariasis: observations of “dancing megasperm” on high-resolution sonography in patients from nonendemic areas mimicking the filarial dance and a proposed mechanism for this phenomenon. J Ultrasound Med 2011; 30:1145–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke L, Edwards A, Graham E. Acoustic streaming: an in vitro study. Ultrasound Med Biol 2004; 30:559–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]