Abstract

We presented a pediatric case with a history of intermittent melena for 3 years because of angiodyplasia of small intestine. The results of frequent upper gastrointestinal endoscopies and colonoscopies as well as both 99mTc-red blood cell (RBC) and Meckel's scintigraphies for several times were negative in detection of bleeding site. However, 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)/computed tomography (CT) after heparin augmentation detected a site of bleeding in the distal ileum which later was confirmed during surgery with final diagnosis of angiodysplasia.

It could be stated that heparin provocation of bleeding before 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy accompanied by fused SPECT/CT images should be kept in mind for management of intestinal bleeding especially in difficult cases.

INTRODUCTION

Bleeding from small-intestine is responsible for the majority of cases of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) and is difficult to be detected and localized.1 Different imaging methods such as angiography and capsule endoscopy are suggested for work-up of these patients.2 Among nuclear medicine procedures, 99mTc-red blood cell (RBC) scintigraphy is also known as a sensitive method for detection and localization of intestinal bleeding.3 Despite using variable imaging techniques, some patients still may remain undiagnosed usually because of small amount or intermittent nature of intestinal bleeding.2 Our patient had also undergone many work-ups during 3 years with no effective results gained. However, modification in method of conventional 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy by provocation of bleeding with heparin and addition of single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)/computed tomography (CT) helped in the detection of bleeding origin.

Presenting Concerns

The subject of this report is a 16-year-old girl who was referred to our nuclear medicine department for 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy. She had been admitted in our hospital because of melena and acute bleeding. The patient had history of intermittent melena for 3 years. With initial presentation of melena, which was also associated with bloody vomiting, upper endoscopy revealed a clear bed duodenal ulcer; however, because of lack of appropriate response to medical therapy, truncal vagotomy was done for her. However, the patient failed to respond to these therapies and intermittently presented with other episodes of melena and hemoglobin (Hb) level drop (every 2–3 months, on average). During 2 years, endoscopic and colonoscopic examinations were performed for >10 times, all of them revealed no significant abnormality to explain the patient's symptoms. Other work-ups for evaluation of underlying inflammatory diseases (rheumatologic diseases and inflammatory bowel disease) as well as 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy and Meckel's scintigraphy were also negative, for several times within the last 2 years.

Clinical Findings

In the last admission, the patient presented with Hb 6.7 g/dL and hematocrit 21.3%. The patient complained of melena and mild abdominal pain since 2 days before admission. On physical examination, the patient was pale with blood pressure of 100/80 mm Hg. Other examinations were unremarkable. Upper endoscopy revealed angiodysplasic pattern with no evidence of active bleeding. The patient was referred for 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy. Immediately after injection of 20 mL 99mTc-labeled RBC, dynamic 1-minute images were acquired in anterior projection for 1 hour. Then, static images at 2 to 4 hours interval were obtained up to 24 hours, which showed no evidence of abnormal radiotracer accumulation (Figure 1).

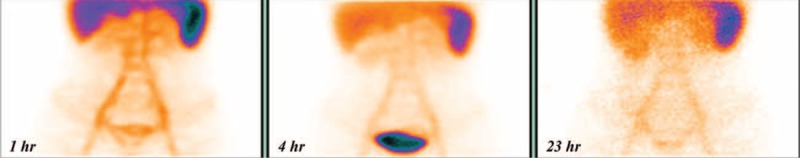

FIGURE 1.

99mTc-RBC scintigraphy. Planar anterior projection in 3 different times 1, 4, and 24 hours after injection of 99mTc-labeled RBCs. The images are negative for gastrointestinal bleeding.

Diagnostic Focus and Assessment

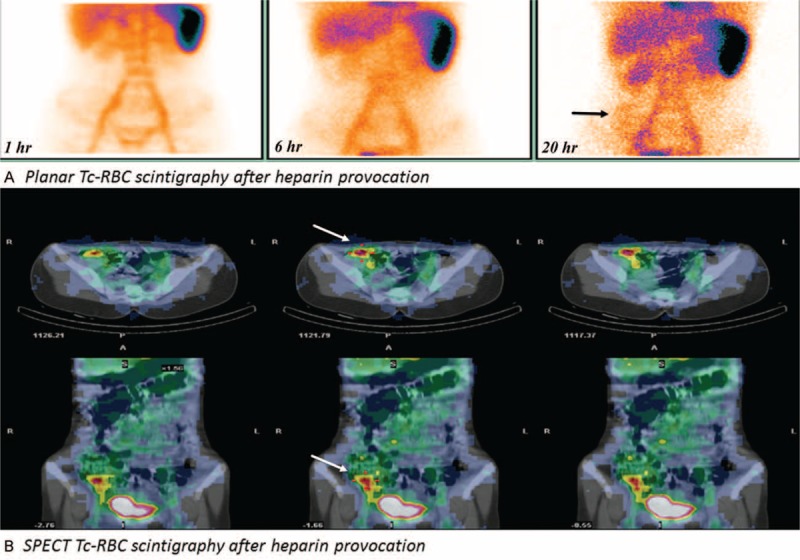

Despite the previous negative result, we decided to repeat the 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy after provocation of bleeding with heparin. Because this procedure was performed as a part of patient's work-up without any research purposes, ethical approval was waived. However, informed consent was given from the patient and her parents. A 20 mL whole blood was obtained from the patient, and after in vitro labeling with 666 MBq99mTc-pertechnetate the patient was reinjected. One hour after reinjection of labeled RBCs, 6000 units heparin was administered intravenously as a loading dose and continued by 1000 units IV heparin/h as previously recommended by some authors.4,5 Close monitoring of the patient was done, and protamine sulfate as an antidote and surgical coverage as a precautionary measure were also available. Dynamic images were obtained in anterior projection at a rate of 1 min/frame for 1 hour and static anterior and posterior images were acquired till 20 hours. After 20 hours a suspicious area of increased activity was noted in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen (Figure 2A). SPECT/CT imaging was performed with a hybrid SPECT/low-dose multislice CT system (Infinia-Hawkeye-4 slice, GE Healthcare System. Milwaukee, WI, USA). SPECT was done with 30 projections in 360 arc (60 s/projection) in step and shoot mode. The fused SPECT/CT images demonstrated an abnormal focus of intraluminal accumulation of radiotracer around the region of ileo-cecal junction (proximal cecum or distal ileum) with anterograde and retrograde extension of activity (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

99mTc-RBC scintigraphy. Anterior planar image (A) at 20 hours following injection of 99mTc-labeled RBCs reveals a suspicious area in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. Transaxial and coronal slices of hybrid SPECT/CT of abdomen (B) confirmed an abnormal focus of intraluminal accumulation of radiotracer around the region of ileo-cecal junction (proximal cecum or distal ileum) with anterograde and retrograde extension of activity.

Therapeutic Focus and Assessment

After the positive result of 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy, the patient was referred to surgeon for exploratory laparotomy and enteroscopy. During exploratory laparotomy, 2 sites of bleeding were seen in the distal ileum, and 10 cm of the ileum was removed which later was confirmed as angiodysplasia histologically.

Follow-Up and Outcomes

The patient was discharged with Hb 10 g/dL, which is still remained stable during 1-year follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Small intestine bleeding is responsible for the majority of cases of OGIB which is difficult to detect and localize. The most common causes are vascular ectasias and tumors. Meckel's diverticulum is the most common cause of significant lower gastrointestinal bleeding in children, decreasing in frequency as a cause of bleeding with age. Small-bowel tumors account for most cases of OGIB in adults; however, in older adults, vascular ectasias are more prevalent.1 Intestinal angiodysplasia which is a type of vascular ectasia is referred to a thin-walled, dilated, punctuate red vascular structure in the mucosa or submucosa of the bowel and is known as a rare cause of intestinal bleeding in children.6–9 In a recent study by Chuang et al,8 the ascending colon and terminal ileum were found to be the most common sites of angiodysplasia in pediatric patients. Although noninvasive techniques such as computed tomographic angiography can be used in the diagnosis of angiodysplasia, the diagnostic standard methods are still angiography and endoscopy which could be too invasive in children.299mTc-RBC scintigraphy can be used as a guide for a more limited angiography or endoscopic techniques by detecting the region of active bleeding.3

This report emphasizes the role of heparin augmented 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy with SPECT/CT in localizing the origin of OGIB. Provocation of gastrointestinal bleeding has also been used before with other imaging modalities such as angiography and with other provocative agents in a few previous reports.10–12 Although the idea of heparin provocation before 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy has been suggested in 1988 by Murphy et al,5 there are few reports in the literature about the use of this technique.4,13 The recommended heparin dose is 6000 units of heparin intravenously as a loading dose 1 hour after the injection of 99mTc-labeled RBCs followed by 1000 units IV heparin/h.4,5 Considering the iatrogenic provocation of an active bleeding process, this procedure should be performed with caution including the intensive monitoring and surgical coverage as well as availability of protamine sulfate and blood for prompt reversal of adverse effects, despite lack of any report on incidence of complications. This technique should be considered only if the other conventional studies remain inconclusive. The patients should also be screened and evaluated for risk of complications because of heparin infusion.4 Brünnler et al13 reported that heparin provocation before 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy can lead to an additional 46% of positive result in previously negative scintigraphies.

With introduction of SPECT/CT for better localization of bleeding origin in 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy,14–16 it seems that combination of both techniques can optimize the accuracy of 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy. Regarding the noninvasive nature of 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy and a lower rate of complications, as well as the ability for detection of intermittent bleeding, 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy with SPECT/CT can be a suitable imaging modality after provocation of gastrointestinal bleeding in cases of OGIB.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography, Hb = hemoglobin, OGIB = obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, RBC = red blood cell, SPECT = single-photon emission computed tomography.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Longo D, Fauci A, Kasper D, et al. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th edUSA: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filippone A, Cianci R, Milano A, et al. Obscure and occult gastrointestinal bleeding: comparison of different imaging modalities. Abdom Imaging 2012; 37:41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dam HQ, Brandon DC, Grantham VV, et al. The SNMMI procedure standard/EANM practice guideline for gastrointestinal bleeding scintigraphy 2.0. J Nucl Med Technol 2014; 42:308–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakalar RS, Tourigny PR, Silverman ED, et al. Provocative red blood cell scintiscan in occult chronic gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Clin Nucl Med 1994; 19:945–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy WD, Di Simone RN, Wolf BH, et al. The use of heparin to facilitate bleeding in technetium-99m RBC imaging. J Nucl Med 1988; 29:725–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de la Torre Mondragón L, Gómez MAV, Tiscarreño MAM, et al. Angiodysplasia of the colon in children. J Pediatr Surg 1995; 30:72–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdoon H. Angiodysplasia in a child as a cause of lower GI bleeding: case report and literature review. Oman Med J 2010; 25:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chuang F-J, Lin J-S, Yeung C-Y, et al. Intestinal angiodysplasia: an uncommon cause of gastrointestinal bleeding in children. Pediatr Neonatol 2011; 52:214–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh S, Gupta R, Mandal A. Angiodysplasia of colon in a seven-year-old boy: a rare cause of intestinal bleeding. J Postgrad Med 2007; 53:278–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingle SB, Alexander JA. Recurrent obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: time for provocative thinking? Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 3:571–573. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar A, Gandolfo F, Halwan B. Provocation of bleeding during endoscopy in patients with recurrent acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 3:570. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rieder F, Schneidewind A, Bolder U, et al. Use of anticoagulation during wireless capsule endoscopy for the investigation of recurrent obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy 2006; 38:526–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brünnler T, Klebl F, Mundorff S, et al. Significance of scintigraphy for the localization of obscure gastrointestinal bleedings. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14:5015–5019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bentley BS, Tulchinsky M. SPECT/CT helps in localization and guiding management of small bowel gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Clin Nucl Med 2014; 39:94–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schillaci O, Spanu A, Tagliabue L, et al. SPECT/CT with a hybrid imaging system in the study of lower gastrointestinal bleeding with technetium-99m red blood cells. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2009; 53:281–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yama N, Ezoe E, Kimura Y, et al. Localization of intestinal bleeding using a fusion of Tc-99m-labeled RBC SPECT and X-ray CT. Clin Nucl Med 2005; 30:488–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]