Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Abstract

Preoperative biliary drainage (PBD) prior to pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) is still controversial; therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the impact of PBD on complications following PD.

A meta-analysis was carried out for all relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective and retrospective studies published from inception to March 2015 that compared PBD and non-PBD (immediate surgery) for the development of postoperative complications in PD patients. Pooled odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were estimated using fixed-effect analyses, or random-effects analyses if there was statistically significant heterogeneity (P < 0.05).

Eight RCTs, 13 prospective studies, 20 retrospective studies, and 3 Chinese local retrospective studies with 6286 patients were included in this study. In a pooled analysis, there were no significant differences between PBD and non-PBD group in the risks of mortality, morbidity, intra-abdominal abscess, sepsis, hemorrhage, pancreatic leakage, and biliary leakage. However, subgroup analysis of RCTs yielded a trend toward reduced risk of morbidity in PBD group (OR 0.48, CI 0.24 to 0.97; P = 0.04). Compared with non-PBD, PBD was associated with significant increase in the risk of infectious complication (OR 1.52, CI 1.07 to 2.17; P = 0.02), wound infection (OR 2.09, CI 1.39 to 3.13; P = 0.0004), and delayed gastric emptying (DGE) (OR 1.37, CI 1.08 to 1.73; P = 0.009).

This meta-analysis suggests that biliary drainage before PD increased postoperative infectious complication, wound infection, and DGE. In light of the results of the study, PBD probably should not be routinely carried out in PD patients.

INTRODUCTION

Although the mortality rate for pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) has fallen to approximately 5% in the last 20 years because of improvements in perioperative care and operative management, the morbidity rate remains as high as 40%.1 Preoperative biliary drainage (PBD) was considered to reduce postoperative complication rate after PD for the first time in 1935 by Whipple et al.2 Drainage can be accomplished either externally, by inserting a transhepatic catheter into the biliary tract percutaneously, or internally, by endoscopic retrograde cannulation of the bile duct with insertion of an endoprosthesis. Both techniques are used safely, but the potential benefit of biliary decompression on postoperative morbidity remains controversial.3

Despite effective reducing levels of jaundice, the majority of studies defining the role of PBD for the development of postoperative complications are with conflicting results. Several experimental studies and retrospective case series have suggested that PBD reduced morbidity and mortality after surgery.3–5 However, some current studies showed a deleterious effect of PBD on postoperative infectious complications, including wound infection and/or intra-abdominal abscess (IAA).6–9 More recently, one randomized controlled trial (RCT) in 2010 has suggested that PBD increased the rate of complications and should not be performed routinely.10 Nevertheless, PBD has been incorporated into the surgical treatment of cancer of the pancreatic head in many centers.11–13 In other words, the safety of routine PBD for obstructive jaundice has not been established. To assess the benefits and harms of PBD versus non-PBD (direct surgery) in patients with obstructive jaundice (irrespective of a benign or malignant cause), 7 meta-analyses9,14–19 from 2002 to 2013 have been reported. The previous meta-analyses were mostly focused on postoperative overall morbidity and mortality, without systematic analysis of various postoperative complications. On the contrary, trials included in these meta-analyses were not comprehensive. The previous meta-analysis in 2013 also concentrated on postoperative morbidity and mortality based on 6 RCTs, and did not include recent nonrandomized studies to analyze postoperative complications in detail, which may no longer be in line with modern surgical practice.

Therefore, this study was to find and update sufficient evidence to support or refute routine PBD for PD patients with obstructive jaundice in clinical practice based on randomized and nonrandomized trials, as well as Chinese local relevant studies, to guide clinicians in their management of these patients.

METHODS

Search Strategy

Electronic databases including PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE Databases, Web of Science, the Cochrane library, Wanfang Data, CNKI database, and scholar.google.com were searched by using the keyword “preoperative biliary drainage” and “obstructive jaundice.” All the articles were published before March 2015. Reference lists of identified studies were scrutinized to reveal additional sources. This study was subject to approval by the Research Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital.

Criteria for Study Selection

Studies were considered for inclusion based upon the following criteria: patients underwent PD with obstructive jaundice; studies with PBD and non-PBD groups; and studies with postoperative mortality and incidence of complications assessed. The main exclusion criteria were as follows: studies not in English or Chinese language; studies with unretrievable or unclear data; studies that were reviews, comments, or replies, and meta-analyses; studies that used duplicated data; and studies that contained <10 patients in either intervention arm.

Data Extraction

Data was extracted independently by 2 investigators. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or a third author adjudication. The following data were abstracted from each study: study group, year, number of included patients, postoperative mortality, incidence of postoperative complication, infectious complication, wound infection, IAA, sepsis, delayed gastric emptying (DGE), pancreatic leakage, biliary leakage, and hemorrhage.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted this meta-analysis in line with the guidelines of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0.20 Treatment effects of the measures are represented as the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for binary variables. The Mantel–Haenszel method was used to combine the OR for the outcomes of interest. The presence of heterogeneity across trials was assessed using a standard χ2 test with the level of significance set at P <0.05 and also evaluated via I2 statistic with the level of significance set at I2 >30%. If heterogeneity was present, a random-effects model was used for meta-analysis. If heterogeneity was not present, the fixed-effect model was applied instead. Furthermore, stratified analysis was conducted based on the study design. The OR, its 95% CI, and heterogeneity of either subgroup were calculated respectively. The subgroup differences were assessed and a P <0.05 was considered representative of statistical significance. In addition, we conducted sensitivity analyses between RCTs, prospective studies, and retrospective studies. Public bias was assessed by visual inspection of a funnel plot. All statistical analyses were performed with the Review Manager Version 5.2 (Cochrane Collaboration, Software Update, Oxford, UK).

RESULTS

Study Selection

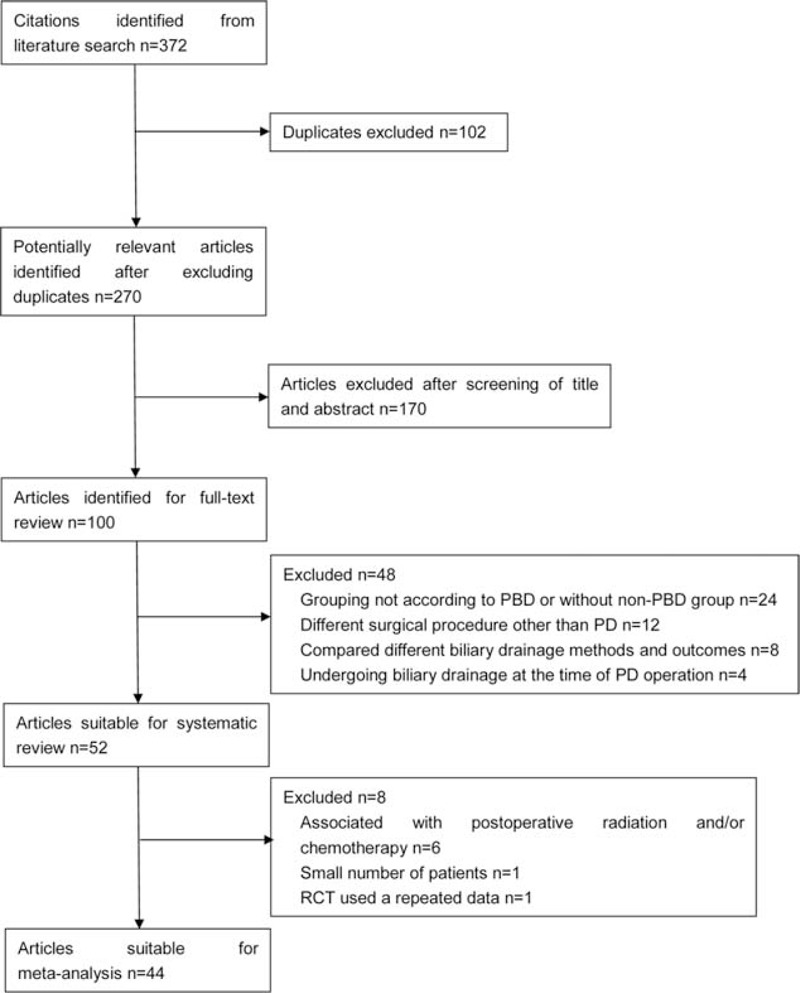

A total of 372 studies were retrieved from PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE Databases, Web of Science, the Cochrane library, Wanfang Data, CNKI database, and scholar.google.com. After the duplicates were identified and excluded, 270 studies were left. Then, we also excluded the articles not written in English or Chinese, reviews comments, or replies, and meta-analyses, leaving 100 studies that were found to be relevant were closely reviewed. At last a total of 44 studies were included and analyzed (Figure 1), including 8 RCTs,10,21–27 13 prospective studies,6,12,13,28–37 20 retrospective studies,8,38–56 and 3 Chinese local retrospective studies57–59 with 6286 patients. Among 8 RCTs, only 1 RCT in 2010 detected specifically the incidence of different postoperative complications. The results of meta-analyses are summarized in Table 1. Two reviewers achieved complete consensus in applying the eligibility criteria.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart showing literature search strategies.

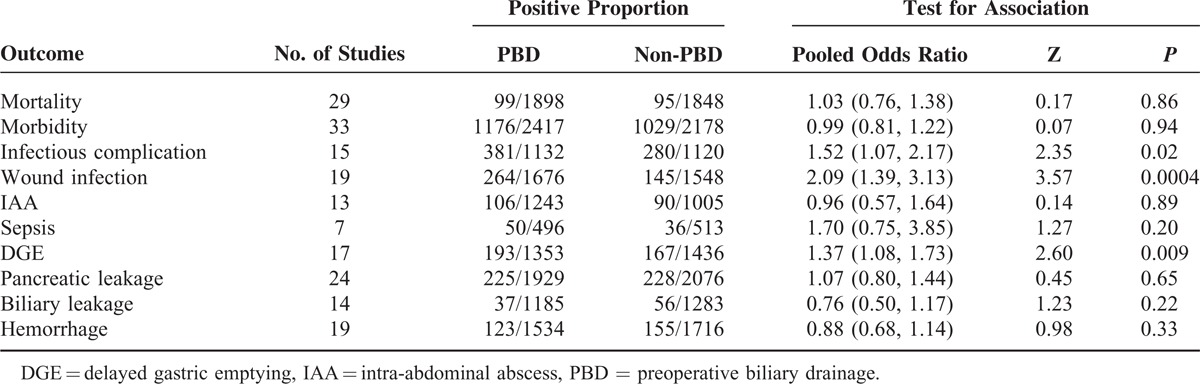

TABLE 1.

Summary of Pooled Odds Ratios in the Meta-Analysis

Mortality

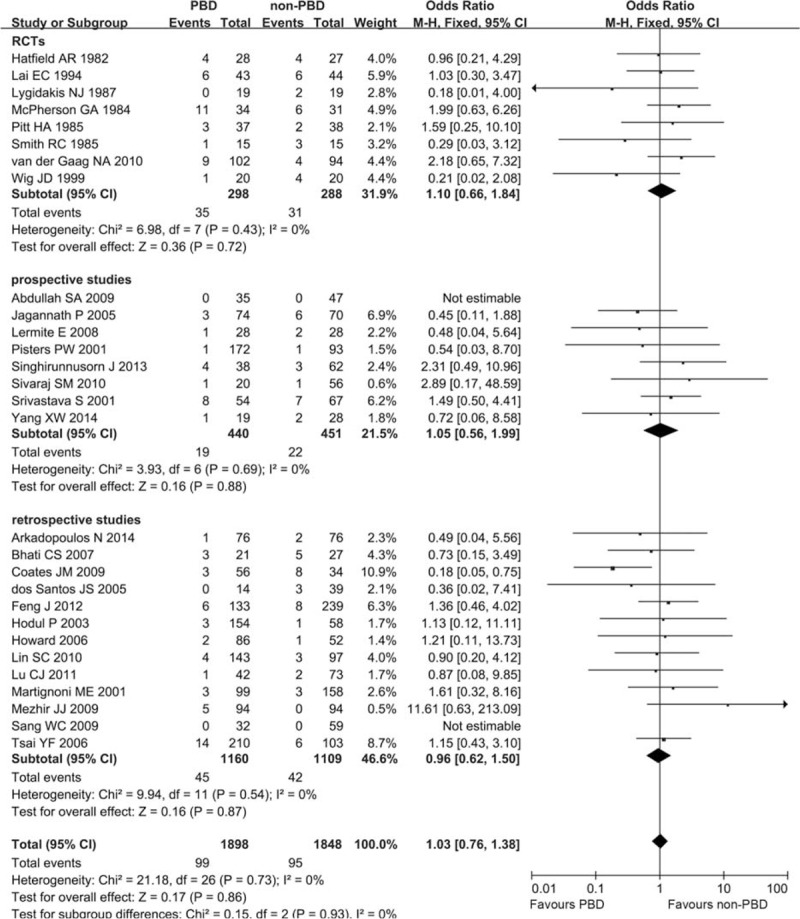

Twenty-nine trials, including 8 RCTs, reported the incidence of postoperative overall mortality. In a pooled analysis of all studies, there was no significant difference between the PBD and non-PBD groups for mortality. In general, it occurred in 99 patients (5.22%, 99/1898) in the PBD group and 95 patients (5.14%, 95/1848) in the non-PBD group (OR 1.03, CI 0.76 to 1.38; P = 0.86). Subgroup analysis by study design, RCTs (OR 1.10, CI 0.66 to 1.84; P = 0.72), prospective studies (OR 1.05, CI 0.56 to 1.99; P = 0.88), and retrospective studies (OR 0.96, CI 0.62 to 1.50; P = 0.87), yielded similar results (Figure 2). There was no significant heterogeneity for all studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.73). The heterogeneity remains no significance for RCTs (I2 = 0%, P = 0.43), prospective studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.69), and retrospective studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.54). No subgroup difference between RCTs, prospective studies, and retrospective studies was observed (P = 0.93).

FIGURE 2.

Meta-analysis of postoperative mortality with PBD versus non-PBD. A Mantel–Haenszel method was used for meta-analysis. Odds ratios are shown with 95% CI. CI = confidence interval, PBD = preoperative biliary drainage.

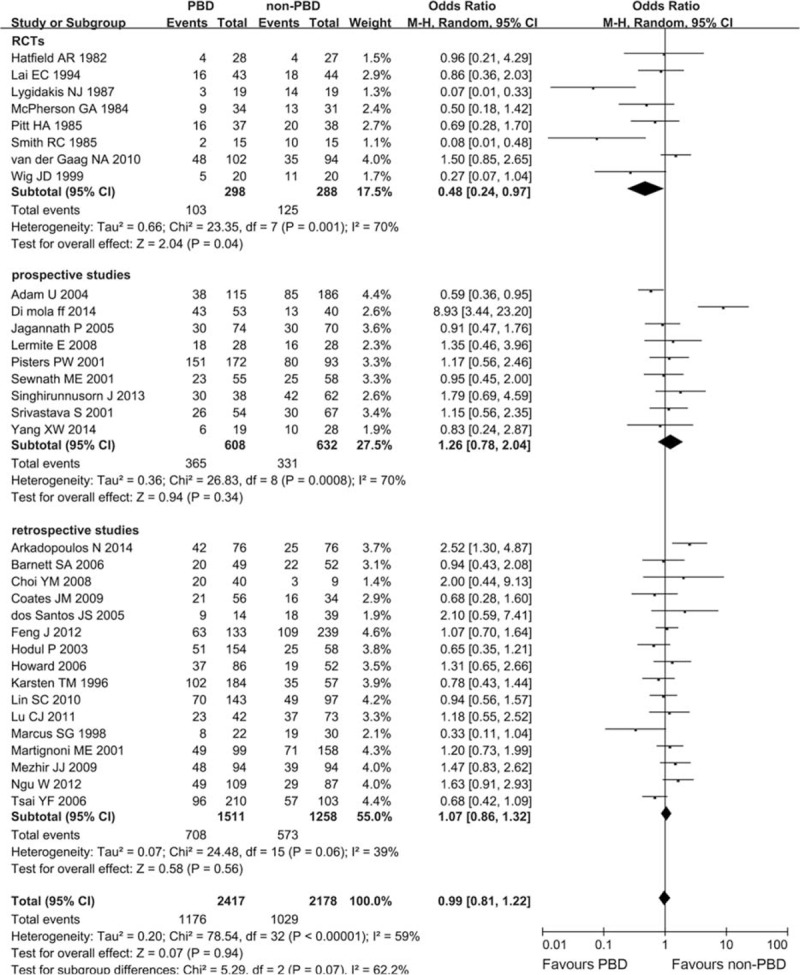

Morbidity

Thirty-three trials, including 8 RCTs, compared PBD with non-PBD and reported the incidence of postoperative complications. Overall, there was no statistically significant difference in morbidity rate between patients who had PBD compared with those who did not (1176/2417, 48.66% vs 1029/2178, 47.25%, respectively; OR 0.99, CI 0.81 to 1.22; P = 0.94). Subgroup analysis by study design, RCTs yielded a trend toward reduced risk of morbidity in PBD group (OR 0.48, CI 0.24 to 0.97; P = 0.04), whereas prospective studies (OR 1.26, CI 0.78 to 2.04; P = 0.34) and retrospective studies (OR 1.07, CI 0.86 to 1.32; P = 0.56) did not yield similar results. There was significant heterogeneity for all studies (I2 = 59%, P < 0.00001). The heterogeneity remains significant for RCTs (I2 = 70%, P = 0.001), prospective studies (I2 = 70%, P = 0.0008), and retrospective studies (I2 = 39%, P = 0.06) (Figure 3). No subgroup difference between RCTs, prospective studies, and retrospective studies was observed (P = 0.07). And no obvious publication bias was found (Figure S1, http://links.lww.com/MD/A340).

FIGURE 3.

Meta-analysis of postoperative morbidity with PBD versus non-PBD. A Mantel–Haenszel method was used for meta-analysis. Odds ratios are shown with 95% CI. CI = confidence interval, PBD = preoperative biliary drainage.

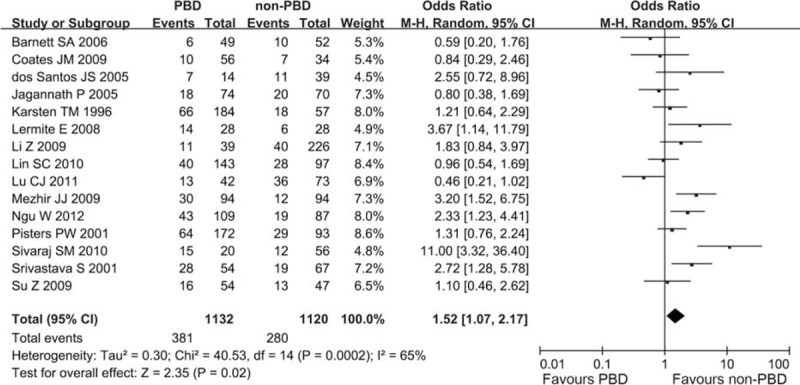

Postoperative Infectious Complication

Fifteen trials with 2252 patients provided available data about the frequency of postoperative infectious complication. And no RCT was included. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed (I2 = 65%, P = 0.0002), and a random-effects model was applied. The weighted mean clinically relevant postoperative infection rate in the PBD group was 33.66% and that in the non-PBD group was 25%. A statistically significant difference was observed between the 2 groups in the meta-analysis (OR 1.52, CI 1.07 to 2.17; P = 0.02) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Meta-analysis of postoperative infectious complication with PBD versus non-PBD. A Mantel–Haenszel method was used for meta-analysis. Odds ratios are shown with 95% CI. CI = confidence interval, PBD = preoperative biliary drainage.

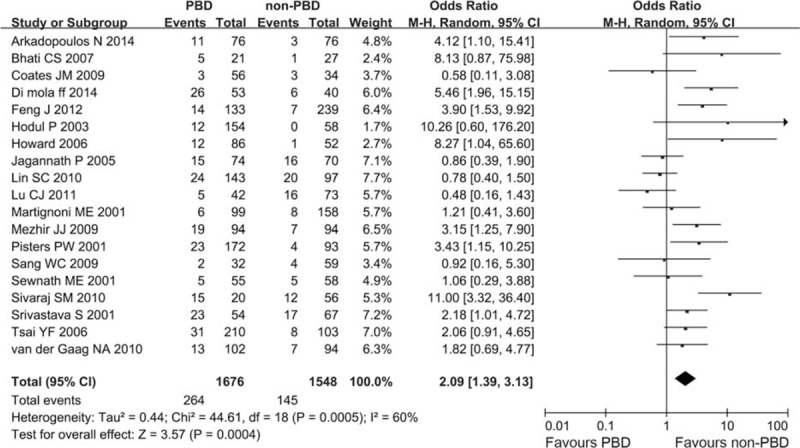

Postoperative Wound Infection

Nineteen trials with 3224 patients comparing PBD with non-PBD showed that PBD had a significantly higher incidence of postoperative wound infection than non-PBD (15.75% vs 9.37%). Only 1 RCT was included. Heterogeneity was observed in this meta-analysis (I2 = 60%, P = 0.0005). In a random-effects model, the difference was statistically significant, and the combined OR was 2.09 (CI 1.39 to 3.13; P = 0.0004) (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Meta-analysis of postoperative wound infection with PBD versus non-PBD. A Mantel–Haenszel method was used for meta-analysis. Odds ratios are shown with 95% CI. CI = confidence interval, PBD = preoperative biliary drainage.

Postoperative Sepsis and Intra-Abdominal Abscess

Seven trials reported the incidence of postoperative sepsis. In general, it occurred in 50 patients (10.08%, 50/496) in the PBD group and 36 patients (7.02%, 36/513) in the non-PBD group. Although there was a trend favoring the non-PBD group, no statistically significant difference was observed between the 2 groups in the meta-analysis (OR 1.70, CI 0.75 to 3.85; P = 0.20) (Figure S2, http://links.lww.com/MD/A340). Thirteen studies investigated the incidence of postoperative IAA, and only 1 RCT was included. Taking all the data together, the PBD group was associated with a minor trend toward a reduced risk of IAA (OR 0.96, CI 0.57 to 1.64; P = 0.89), although the difference was not statistically significant (Figure S3, http://links.lww.com/MD/A340).

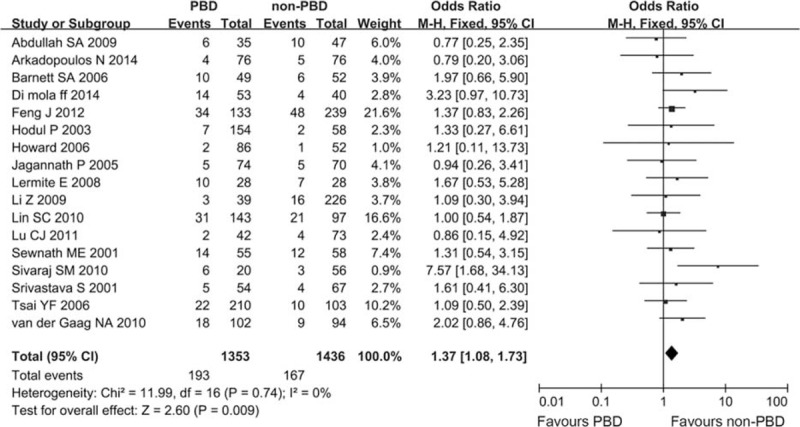

Incidence of Postoperative DGE

The meta-analysis of 17 studies with 2789 patients comparing PBD with non-PBD showed that the PBD group had a significantly higher incidence of DGE than the non-PBD group (14.26% vs 11.63%). One RCT was included, and subgroup analysis in line with the study design was not carried out. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed (I2 = 0%, P = 0.74). In a fixed-effect model, there was a significant between-group difference, and the combined OR was 1.37 (CI 1.08 to 1.73; P = 0.009) (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Meta-analysis of postoperative delayed gastric emptying with PBD versus non-PBD. A Mantel–Haenszel method was used for meta-analysis. Odds ratios are shown with 95% CI. CI = confidence interval, PBD = preoperative biliary drainage.

Pancreatic Leakage, Biliary Leakage, and Hemorrhage

Twenty-four studies provided data on PBD versus non-PBD for the incidence of postoperative pancreatic leakage. There was a moderate level of heterogeneity (I2 = 41%, P = 0.02). In the random-effects model, there was no statistically significant difference between these 2 groups (OR 1.07, CI 0.80 to 1.44; P = 0.65) (Figure S4, http://links.lww.com/MD/A340). The incidence of postoperative biliary leakage was reported in 14 studies. Rate of postoperative biliary leakage was not significantly different in PBD and non-PBD groups (3.12% vs 4.36%; OR 0.76, CI 0.50 to 1.17; P = 0.22) (Figure S5, http://links.lww.com/MD/A340). The incidence of postoperative hemorrhage was reported in 19 studies. Overall, there was no statistically significant difference in the risk of postoperative hemorrhage between patients who had PBD compared to those who did not (8.02% vs 9.03%; OR 0.88, CI 0.68 to 1.14; P = 0.33) (Figure S6, http://links.lww.com/MD/A340).

Sensitivity Analyses

As prospective and retrospective studies were pooled with the RCTs in the analysis of mortality and morbidity, sensitivity analysis to subtotal the plots by RCTs versus prospective studies versus retrospective studies was conducted, and no significant differences of OR between RCTs, and prospective and retrospective studies were detected (all P > 0.05; Figures 2 and 3).

DISCUSSION

PBD is generally performed for patients having jaundice with pancreatic head malignancy. Despite theoretical advantages, such as cholangitis, PBD remains controversial because it has not only failed to show a clinical benefit but also suggested an adverse impact on perioperative outcome. The major findings of this study were as follows: first, overall, PBD resulted in a significant increase in the risk of postoperative infectious complication, wound infection, and DGE compared with non-PBD. Second, in general, there were no between-group differences in terms of the risk of postoperative mortality, morbidity, IAA, sepsis, pancreatic leakage, biliary leakage, and hemorrhage. PBD was demonstrated to increase postoperative infectious complications in the previous studies,31,38,44,60 which is consistent with our findings. Wound infection after surgery was defined as a culture-positive collection that resulted in a hospital stay of >2 weeks or as wound sepsis that required secondary suturing or refashioning. In the present study, the incidence of postoperative wound infection was significantly different in patients with or without PBD, and PBD probably increases the rates of postoperative wound infection by about 6%, which is consistent with other reports.8,12,13,27,30,34,36,39,44,51,57,60,61 DGE was defined as the need for nasogastric tube drainage for ≥7 days postoperatively or the need for reinsertion after removal. As demonstrated in our study, the incidence of postoperative DGE was increased in patients with PBD compared with those with immediate surgery. The underlying mechanism of DGE is still unclear, but many authors suggest that the local inflammation induced by the leaked pancreatic enzymes may play an important role.62,63

However, 8 of the studies used in the meta-analysis were RCTs, and only 1 RCT in 2010 specifically detected the incidence of different postoperative complications. In order to define whether PBD was associated with increased specific postoperative complications, prospective and retrospective studies were included. Therefore, this must be considered as a weakness in this study. Second, RCTs were pooled with the prospective and retrospective studies in the analyses of mortality and morbidity. We conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine the effects of RCTs, and prospective and retrospective studies. There was no significant difference of OR between RCTs, and prospective and retrospective studies (Figures 2 and 3). So even for compiled retrospective studies, the same conclusion could be drawn. However, there was heterogeneity in the analysis of morbidity, and RCTs yielded a reduced risk of morbidity in PBD group, which is in conflict with the prospective and retrospective studies (Figure 3). This result may be because of the lack of accurate definition and classification of morbidity in the included trials. In addition, mainly because of different study design, RCTs have ruled out many confounding factors, which are different from prospective and retrospective studies. The results were not adjusted for the presence of confounding, which potentially leaded to biased estimates. Therefore, further studies were required to clarify this issue.

It is unclear what factors in PBD affect the incidence of postoperative complications after PD. The short duration of PBD might be the reason for its failure to benefit severely jaundiced patients in several studies. The optimal duration of biliary drainage before surgery has not been established. Even if the bilirubin level has decreased to normal levels, normal major synthetic and clearance functions of the liver, as well as mucosal intestinal barrier functions will be fully restored only after at least 4 to 6 weeks according to animal studies.3,64 However, whether this nearly complete restoration of liver function can be transformed into better clinical outcome after surgery has not been studied. In fact, in clinical practice, surgery is not usually delayed more than a few weeks except for patients with cholangitis, requiring extensive preoperative assessment (such as liver biopsy) or neoadjuvant treatments. In addition, prolonged PBD causes extensive inflammatory reaction in the bile duct wall leading to difficulties in the subsequent operations, increases the risk of stent-related complications, increases the chance of bacterial colonization of the biliary tree, and delays the definitive surgery.65 It is possible that there may be an optimal duration of biliary drainage before surgery, wherein PBD may help reduce morbidity and mortality in those patients who are deeply jaundiced without increasing biliary drainage-related complication. More large-sized comparative studies are needed to answer this question.

Second, there may be a threshold of bilirubin wherein PBD helps to reduce morbidity and mortality of patients with jaundice,16 or the effect of PBD on postoperative morbidity and mortality may be associated with different bilirubin levels. In this study, such a subgroup analysis was not performed because of the data representation that was not sufficient. Therefore, subsequent studies should focus on the relationship between predrainage bilirubin level and patient's prognosis.

Third, another issue is the selection of internal or external drainage in PBD. Different drainage methods may affect the incidence of postoperative complications after PD. Kitahata et al66 retrospectively reviewed a prospectively maintained database to assess the associations between biliary drainage-related complications and postoperative complications after PD between internal drainage and external drainage. Compared with external drainage, preoperative internal biliary drainage may increase the risk of postoperative complications. However, there are some drawbacks in external drainage, such as the drainage tube may be shifted or pulled out by patients, discomfort or esthetic issues because of the existence of nasopharynx tube in endoscopic nasobiliary drainage, and the invasiveness or seeding risk in percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. In addition, another problem is which kind of stents should be used in internal drainage, plastic or metallic stents. A few studies suggested that in patients awaiting PD, metallic stents have more advantages over plastic stents as for preoperative internal biliary drainage.67–69 Additional studies are required to figure out internal or external drainage, and specific approach for drainage is the optimum method for PBD.

To conclude, the present study suggests that PBD would not benefit patients and additionally it would increase postoperative infectious complications. PBD for PD patients with obstructive jaundice probably should not be routinely carried out. For those patients who can do immediate surgery, obstructive jaundice should not be the contraindication of PD, and immediate surgery is still the first choice. Moreover, PBD should not be performed only for the reason of preoperative biliary decompression, so as to delay surgery. However, a large multicenter RCT of PBD versus immediate surgery for PD patients with obstructive jaundice is required to confirm the present study results and find out the reasons for the occurrence of postoperative complications in PBD.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Haifeng Zhang and Jing Deng for assistance in statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, DGE = delayed gastric emptying, IAA = intra-abdominal abscess, OR = odds ratio, PBD = preoperative biliary drainage, PD = pancreatoduodenectomy, RCTs = randomized controlled trials.

YC, GO and GL equally contributed to this work.

Author Contributions—Conceived and designed the experiments: YC and YH; Performed the experiments: YC and GO; Analyzed the data and contributed analysis tools: GO, GL, and HL; Wrote the article: YC and GO; Independent literature searching and data extraction: GL, KH and HL.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81302140), National Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong, China (Grant No. 2014A030313050), Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (Grant No. 20130171120093), Grant [2013]163 from Key Laboratory of Malignant Tumor Molecular Mechanism and Translational Medicine of Guangzhou Bureau of Science and Information Technology; and Grant KLB09001 from the Key Laboratory of Malignant Tumor Gene Regulation and Target Therapy of Guangdong Higher Education Institutes.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Website (www.md-journal.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Gouma DJ, van Geenen RC, van Gulik TM, et al. Rates of complications and death after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and the impact of hospital volume. Ann Surg 2000; 232:786–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whipple AO, Parsons WB, Mullins CR. Treatment of carcinoma of the ampulla of vater. Ann Surg 1935; 102:763–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Gaag NA, Kloek JJ, de Castro SM, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage in patients with obstructive jaundice: history and current status. J Gastrointest Surg 2009; 13:814–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klinkenbijl JH, Jeekel J, Schmitz PI, et al. Carcinoma of the pancreas and periampullary region: palliation versus cure. Br J Surg 1993; 80:1575–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimmings AN, van Deventer SJ, Obertop H, et al. Endotoxin, cytokines, and endotoxin binding proteins in obstructive jaundice and after preoperative biliary drainage. Gut 2000; 46:725–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jagannath P, Dhir V, Shrikhande S, et al. Effect of preoperative biliary stenting on immediate outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 2005; 92:356–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cortes A, Sauvanet A, Bert F, et al. Effect of bile contamination on immediate outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy for tumor. J Am Coll Surg 2006; 202:93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard TJ, Yu J, Greene RB, et al. Influence of bactibilia after preoperative biliary stenting on postoperative infectious complications. J Gastrointest Surg 2006; 10:523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Velanovich V, Kheibek T, Khan M. Relationship of postoperative complications from preoperative biliary stents after pancreaticoduodenectomy. A new cohort analysis and meta-analysis of modern studies. JOP 2009; 10:24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Gaag NA, Rauws EA, van Eijck CH, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage for cancer of the head of the pancreas. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lillemoe KD. Preoperative biliary drainage and surgical outcome. Ann Surg 1999; 230:143–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sewnath ME, Birjmohun RS, Rauws EA, et al. The effect of preoperative biliary drainage on postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2001; 192:726–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pisters PW, Hudec WA, Hess KR, et al. Effect of preoperative biliary decompression on pancreaticoduodenectomy-associated morbidity in 300 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 2001; 234:47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sewnath ME, Karsten TM, Prins MH, et al. A meta-analysis on the efficacy of preoperative biliary drainage for tumors causing obstructive jaundice. Ann Surg 2002; 236:17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saleh MM, Nørregaard P, Jørgensen HL, et al. Preoperative endoscopic stent placement before pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis of the effect on morbidity and mortality. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56:529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcea G, Chee W, Ong SL, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage for distal obstruction: the case against revisited. Pancreas 2010; 39:119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang Y, Gurusamy KS, Wang Q, et al. Pre-operative biliary drainage for obstructive jaundice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 9:CD005444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu YD, Bai JL, Xu FG, et al. Effect of preoperative biliary drainage on malignant obstructive jaundice: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17:391–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang Y, Gurusamy KS, Wang Q, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials on safety and efficacy of biliary drainage before surgery for obstructive jaundice. Br J Surg 2013; 100:1589–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. http://handbook.cochrane.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai EC, Mok FP, Fan ST, et al. Preoperative endoscopic drainage for malignant obstructive jaundice. Br J Surg 1994; 81:1195–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wig JD, Kumar H, Suri S, et al. Usefulness of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage in patients with surgical jaundice: a prospective randomised study. J Assoc Physicians India 1999; 47:271–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hatfield AR, Tobias R, Terblanche J, et al. Preoperative external biliary drainage in obstructive jaundice. A prospective controlled clinical trial. Lancet 1982; 2:896–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McPherson GA, Benjamin IS, Hodgson HJ, et al. Pre-operative percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage: the results of a controlled trial. Br J Surg 1984; 71:371–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pitt HA, Gomes AS, Lois JF, et al. Does preoperative percutaneous biliary drainage reduce operative risk or increase hospital cost? Ann Surg 1985; 201:545–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith RC, Pooley M, George CR, et al. Preoperative percutaneous transhepatic internal drainage in obstructive jaundice: a randomized, controlled trial examining renal function. Surgery 1985; 97:641–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lygidakis NJ, van der Heyde MN, Lubbers MJ. Evaluation of preoperative biliary drainage in the surgical management of pancreatic head carcinoma. Acta Chir Scand 1987; 153:665–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdullah SA, Gupta T, Jaafar KA, et al. Ampullary carcinoma: effect of preoperative biliary drainage on surgical outcome. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15:2908–2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adam U, Makowiec F, Riediger H, et al. Risk factors for complications after pancreatic head resection. Am J Surg 2004; 187:201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.di Mola FF, Tavano F, Rago RR, et al. Influence of preoperative biliary drainage on surgical outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy: single centre experience. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2014; 399:649–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lermite E, Pessaux P, Teyssedou C, et al. Effect of preoperative endoscopic biliary drainage on infectious morbidity after pancreatoduodenectomy: a case-control study. Am J Surg 2008; 195:442–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rumstadt B, Schwab M, Korth P, et al. Hemorrhage after pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 1998; 227:236–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singhirunnusorn J, Roger L, Chopin-Laly X, et al. Value of preoperative biliary drainage in a consecutive series of resectable periampullary lesions. From randomized studies to real medical practice. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2013; 398:295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sivaraj SM, Vimalraj V, Saravanaboopathy P, et al. Is bactibilia a predictor of poor outcome of pancreaticoduodenectomy? Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2010; 9:65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su Z, Koga R, Saiura A, et al. Factors influencing infectious complications after pancreatoduodenectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2010; 17:174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Srivastava S, Sikora SS, Kumar A, et al. Outcome following pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients undergoing preoperative biliary drainage. Dig Surg 2001; 18:381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang XW, Yuan JM, Chen JY, et al. The prognostic importance of jaundice in surgical resection with curative intent for gallbladder cancer. BMC Cancer 2014; 14:652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnett SA, Collier NA. Pancreaticoduodenectomy: does preoperative biliary drainage, method of pancreatic reconstruction or age influence perioperative outcome? A retrospective study of 104 consecutive cases. ANZ J Surg 2006; 76:563–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhati CS, Kubal C, Sihag PK, et al. Effect of preoperative biliary drainage on outcome of classical pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13:1240–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi YM, Cho EH, Lee KY, et al. Effect of preoperative biliary drainage on surgical results after pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients with distal common bile duct cancer: focused on the rate of decrease in serum bilirubin. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14:1102–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coates JM, Beal SH, Russo JE, et al. Negligible effect of selective preoperative biliary drainage on perioperative resuscitation, morbidity, and mortality in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Arch Surg 2009; 144:841–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.dos Santos JS, Júnior WS, Módena JL, et al. Effect of preoperative endoscopic decompression on malignant biliary obstruction and postoperative infection. Hepatogastroenterology 2005; 52:45–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han HJ, Choi SB, Lee JS, et al. Reliability of continuous suture of pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology 2011; 58:2132–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hodul P, Creech S, Pickleman J, et al. The effect of preoperative biliary stenting on postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg 2003; 186:420–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kajiwara T, Sakamoto Y, Morofuji N, et al. An analysis of risk factors for pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: clinical impact of bile juice infection on day 1. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2010; 395:707–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karsten TM, Allema JH, Reinders M, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage, colonisation of bile and postoperative complications in patients with tumours of the pancreatic head: a retrospective analysis of 241 consecutive patients. Eur J Surg 1996; 162:881–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Z, Zhang Z, Hu W, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with preoperative obstructive jaundice: drainage or not. Pancreas 2009; 38:379–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin SC, Shan YS, Lin PW. Adequate preoperative biliary drainage is determinative to decrease postoperative infectious complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology 2010; 57:698–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marcus SG, Dobryansky M, Shamamian P, et al. Endoscopic biliary drainage before pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary malignancies. J Clin Gastroenterol 1998; 26:125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martignoni ME, Wagner M, Krähenbühl L, et al. Effect of preoperative biliary drainage on surgical outcome after pancreatoduodenectomy. Am J Surg 2001; 181:52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mezhir JJ, Brennan MF, Baser RE, et al. A matched case-control study of preoperative biliary drainage in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma: routine drainage is not justified. J Gastrointest Surg 2009; 13:2163–2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ngu W, Jones M, Neal CP, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage for distal biliary obstruction and post-operative infectious complications. ANZ J Surg 2013; 83:280–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsai YF, Shyu JF, Chen TH, et al. Effect of preoperative biliary drainage on surgical outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology 2006; 53:823–827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Watanabe F, Noda H, Kamiyama H, et al. Risk factors for intra-abdominal infection after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a retrospective analysis to evaluate the significance of preoperative biliary drainage and postoperative pancreatic fistula. Hepatogastroenterology 2012; 59:1270–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yeh TS, Jan YY, Jeng LB, et al. Pancreaticojejunal anastomotic leak after pancreaticoduodenectomy: multivariate analysis of perioperative risk factors. J Surg Res 1997; 67:119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arkadopoulos N, Kyriazi MA, Papanikolaou IS, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage of severely jaundiced patients increases morbidity of pancreaticoduodenectomy: results of a case-control study. World J Surg 2014; 38:2967–2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feng J, Huang ZQ, Chen YL, et al. Influence of obstructive jaundice on postoperative complications and mortality after pancreaticoduodenectomy: analysis of the 25-year single-center data. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 2012; 50:294–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lu CJ, Wang YJ, Du Z, et al. The effect of preoperative percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage on postoperative short-term outcomes. Zhonghua Gan Dan Wai Ke Za Zhi 2011; 17:891–893. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sang WC, He QS, Sun CB. Preoperative biliary drainage in patients with malignant obstructive jaundice of carcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Shandong Da Xue Xue Bao 2009; 47:118–121. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Povoski SP, Karpeh MS, Jr, Conlon KC, et al. Association of preoperative biliary drainage with postoperative outcome following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 1999; 230:131–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Montagne GJ, Lygidakis NJ, van der Heyde MN, et al. Early postoperative complications after (sub)total pancreatoduodenectomy: the AMC experience. Hepatogastroenterology 1988; 35:226–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Niedergethmann M, Farag Soliman M, Post S. Postoperative complications of pancreatic cancer surgery. Minerva Chir 2004; 59:175–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Riediger H, Makowiec F, Schareck WD, et al. Delayed gastric emptying after pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy is strongly related to other postoperative complications. J Gastrointest Surg 2003; 7:758–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hirazawa K, Hazama S, Oka M. Depressed cytotoxic activity of hepatic nonparenchymal cells in rats with obstructive jaundice. Surgery 1999; 126:900–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lai EC, Lau SH, Lau WY. The current status of preoperative biliary drainage for patients who receive pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary carcinoma: a comprehensive review. Surgeon 2014; 12:290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kitahata Y, Kawai M, Tani M, et al. Preoperative cholangitis during biliary drainage increases the incidence of postoperative severe complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg 2014; 208:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aadam AA, Evans DB, Khan A, et al. Efficacy and safety of self-expandable metal stents for biliary decompression in patients receiving neoadjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 76:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Decker C, Christein JD, Phadnis MA, et al. Biliary metal stents are superior to plastic stents for preoperative biliary decompression in pancreatic cancer. Surg Endosc 2011; 25:2364–2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cavell LK, Allen PJ, Vinoya C, et al. Biliary self-expandable metal stents do not adversely affect pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:1168–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]