Abstract

Metaplastic breast carcinoma (MBC) is a rare type of breast carcinoma. Recurrence presenting as chest wall invasion is common but rarely as metastasis to distal skeletal muscle in which most patients present with a painful mass. Herein, we report a rare case of 65-year-old woman, with MBC and recurrence presenting as distal multiple muscle metastasis. The patient received surgical excision for symptomatic relief. Unfortunately, she died 12 months postoperatively due to disease progression with multiple lung metastasis.

In addition to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, surgical excision is an alternative option in selected patients such as those with painful, isolated, and easily approachable mass.

INTRODUCTION

Metaplastic breast carcinoma (MBC) is rare with an incidence less than 1% of all breast malignancies.1 It denotes tumors with mixed primary epithelial and sarcomatous components as well as mixed adenocarcinoma with squamous cell carcinoma and tends to be larger in size when diagnosed, with higher tumor grade and triple-negative for hormone receptors. Expression of estrogen, progesterone, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Her-2/Neu) receptors has been reported in 12%, 9%, and 15%, respectively, of patients with MBC.2 Metastasis commonly occurs to distant organs rather than axillary lymph nodes. The rare incidence of muscular metastasis in all malignancy, as in breast carcinoma, has been reported to range from 0.2% to 17.5% in large autopsy series.3,4 Surgical excision was recommended in selected patients such as those with painful, isolated, easily approachable mass.3 Herein, we report a rare case of MBC with multiple muscle metastasis (MMM).

CASE REPORT

A 65-year-old Taiwanese woman had a history of debulking surgery, bilateral oophorectomy with omentectomy, total anterior hysterectomy with radical pelvic lymph nodes dissection due to ovarian carcinoma (mucinous-type carcinoma, stage Ic) 1 year ago. Patient's medical compliance was poor and failed to complete her chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2, carboplatin 300 mg/m2). Recently, she noted a palpable right breast mass, which enlarged rapidly to about 15 cm in size and nearly occupied the whole right breast in 2 months. Core needle biopsy revealed metaplastic carcinoma. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with the regimens of Taxotere (75 mg/m2), Epirubicin (75 mg/m2), and Cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2) was given for 6 cycles with poor response, followed by a modified radical mastectomy (MRM) with dissection of axillary lymph nodes and skin grafting. Postoperatively, radiotherapy was done with 5000 cGy in 25 fractions. The histopathologic examination revealed a metaplastic carcinoma with myoepithelial and squamous differentiation associated with adenomyoepithelioma (Figure 1A–C). Immunohistochemistry study showed that the tumor cells are positive for epithelial markers–cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) stain, and myoepithelial markers, including cytokeratin 5/6 (CK 5/6), p63, and S100 stains (Figure 2A–E). Expressions of hormone receptors, including ER, PR, and Her-2/Neu, were all negative (Figure 3A–D). The dissected axillary lymph nodes showed metastastic carcinoma with hormone triple-negative in 3 out of 26 nodes. The patient was staged as pT3N1aM0, with histologic tumor grade III.

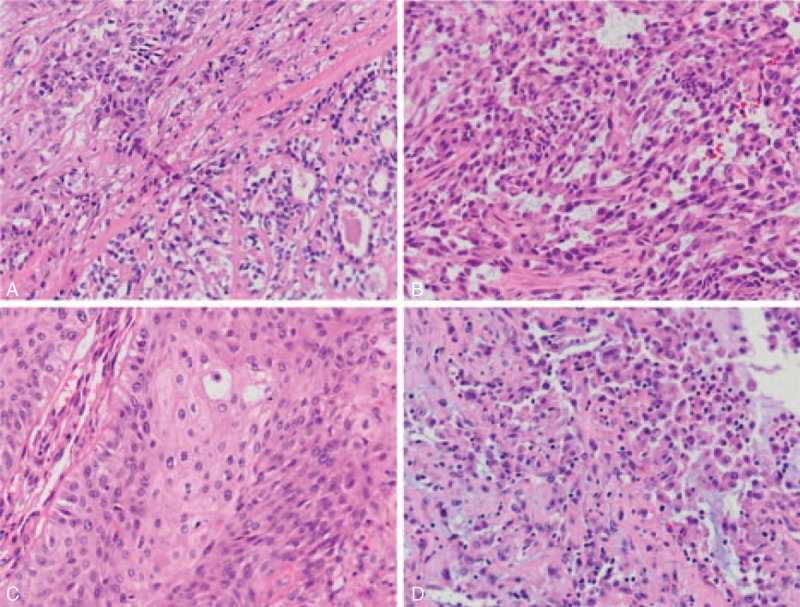

FIGURE 1.

(A) Right lower field shows adenomyoepithelioma with an inner layer of eosinophilic ductal cells and an outer layer of clear myoepithelial cells arranged in a glandular pattern. At the periphery (left upper field), there is myoepithelial carcinoma arranged in cords and nests (H&E stain, 200×). (B) Tumor cells have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei with various shapes, including round, ovoid, plasmacytoid, polygonal, and spindle shapes (H&E stain, 200×). (C) A part of the breast tumor reveals squamous cell carcinoma (H&E stain, 200×). (D) The metastatic tumor over the left forearm reveals round-shaped to spindle-shaped cells, similar to primary tumor shown in (B) (H&E stain, 200×).

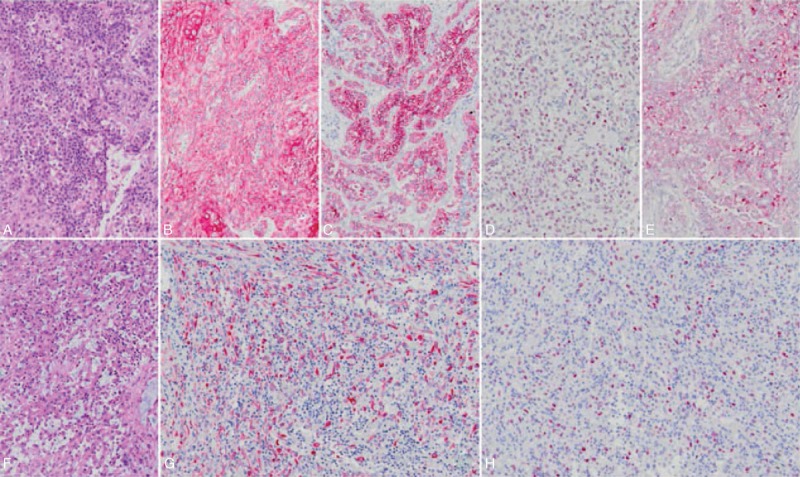

FIGURE 2.

Primary MBC (A, H&E stain, 100×) reveals diffuse expression of cytokeratin (B, 100×), CK5/6 (C, 100×), P63 (D, 100×), and is focally positive for S100 protein (E, 100×) immunohistochemically. The tumor cells of metastastic forearm (F, H&E stain, 100×) are also extensively reactive to cytokeratin (G, 100×) and show nuclear staining of P63 (H, 100×).

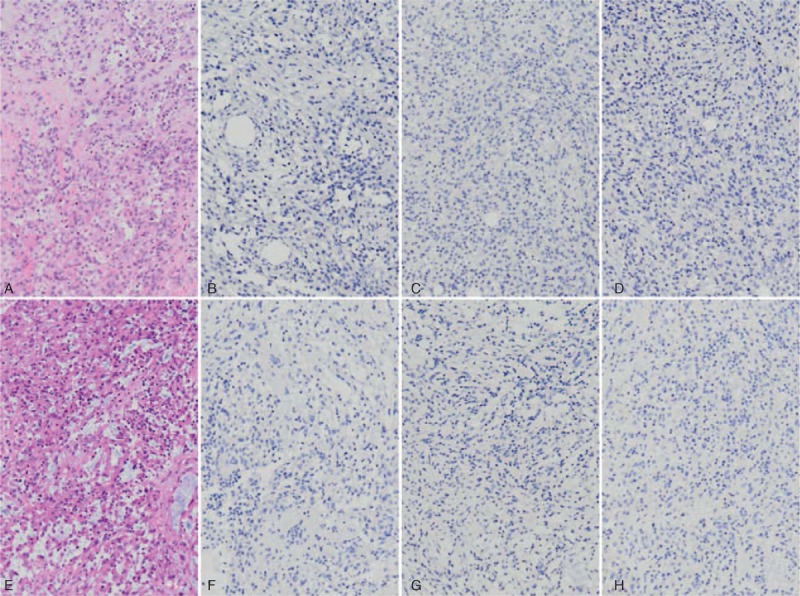

FIGURE 3.

Both the primary MBC (A, 100×) and metastastic forearm (E, 100×) were negative for ER (B and F, 100×), PR (C and G, 100×), and Her-2/Neu (D and H, 100×) immunostains.

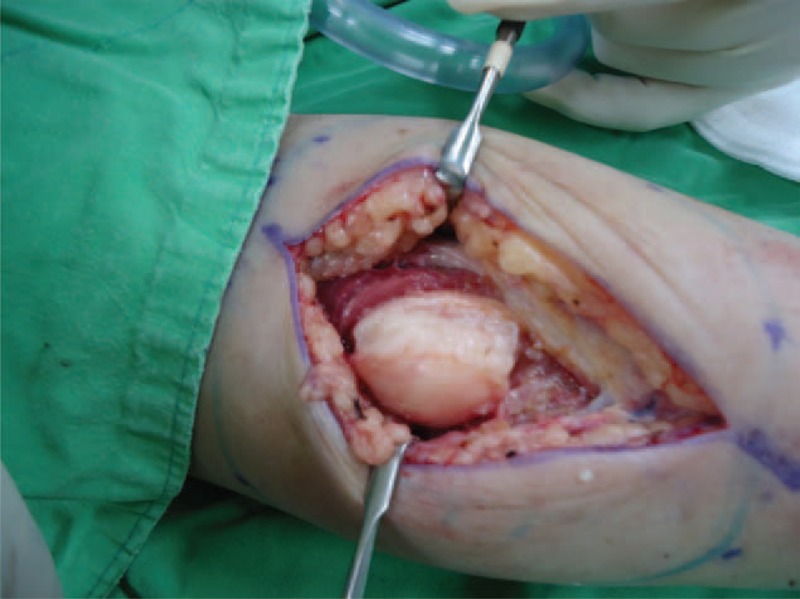

Seven months later, the patient complained about pain and numbness over left forearm, right lower back, and bilateral lower extremities. Fentanyl patch (2.5 mg/q72h) was used for pain control. Sonography of left forearm revealed a tumor with hypervascularity and cystic component, measuring about 6 × 5 cm in size. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/C) scan showed hypermetabolic masses in the left proximal forearm, right psoas, and quadratus lumborum muscles (Figure 4). Surgical excision of left forearm mass (Figure 5) was performed for symptomatic relief of intractable pain. However, excision for the right psoas and quadratus lumborum muscles lesion was not feasible due to high risks of morbidities. Histopathologic examination of left forearm tumor revealed metastatic carcinoma, similar to previous breast cancer with negative ER, PR, and Her-2/Neu immunostaining (Figure 3E–H), positive for epithelial markers–cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) stain, and myoepithelial markers as p63 (Figure 2F–H). Further boosted radiotherapy was added, but the metastatic tumors in the right psoas and quadratus lumborum muscles progressed in size. Eventually, lung metastasis occurred 10 months and she died 12 months later after MRM. The informed consent was obtained from the relative.

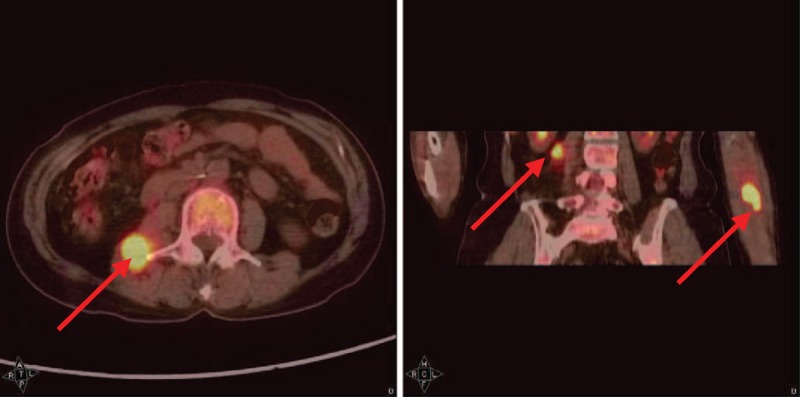

FIGURE 4.

PET/CT scan showed hypermetabolic masses in the left proximal forearm and right psoas to quadratus lumborum muscles.

FIGURE 5.

Gross picture of the left forearm tumor: whitish in color, well encapsulated, 5 × 3 × 3 cm in size. CK = cytokeratin, ER = estrogen receptor, H&E = hematoxylin and eosin, Her-2/Neu = human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, MBC = metaplastic breast carcinoma, PET/CT = positron emission tomography/computed tomography, PR = progesterone receptor.

DISCUSSION

The breast cancer can metastasize anywhere in the body, primarily to the bone, lung, regional lymph nodes, liver, and brain, with the most common site being the bone. Muscle metastasis is rare in breast malignancies compared with bone metastasis and often manifested as a disseminated disease with multiple organ metastasis. PET/CT is considered the most sensitive tool for the diagnosis of muscular metastasis, and has been reported to detect more unsuspected muscular metastasis than computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging.5 Intramuscular hot spots on PET/CT scans should be considered a sign of metastatic lesions even in the absence of any abnormality on computed tomography scans. Muscular pain is a sentinel sign of bone or skeleton muscle metastasis and should be considered a premonition for MBC, as in our case, who died 3 months later after the diagnosis of MMM.

Skeletal muscle metastasis in breast malignancies is uncommon and therapeutic intervention is mainly palliative. Skeletal muscle is relatively resistant to metastatic disease because of its hostile microenvironment, such as muscle motion resulting in mechanical tumor destruction, power of hydrogen from inhospitable muscle, muscle's ability to remove tumor-produced lactic acid associated with angiogenesis, and activation of lymphocytes and natural killer cells in skeletal muscle.3,5,6 MBC invasion directly into pectoral muscles is uncommon, but distal skeleton muscle metastasis is even more rarely. Sites of metastasis that has been reported include extraocular, paraspinal, gluteal, and abdominal wall muscles, which induced symptoms including vision diplopia or intractable pain according to tumor locations.4

Breast malignancy is treated as a systemic disease because the pathophysiological mechanism of metastasis is thru lymphatic drainage to systemic lymph nodes and hematogenous spread to the distal areas. However; the treatment in breast carcinoma, including MBC, with MMM is according to pathologic immunohistochemistry and hormone receptors to choose 3 fundamentally different kinds of drugs, including cytotoxic chemotherapies, hormone therapies, and targeted therapies. In our review of English literature, this is the first case of MBC with distal MMM resulting in intractable pain and numbness, treated with surgical excision for symptomatic relief. Biopsy is adequate for diagnosis; however, total surgical excision, although not curable, should be adopted for symptomatic relief of intractable pain and numbness. The prognosis of MBC with MMM is very poor in our patient who died 1 year after MRM, and the treatment goals are currently for symptomatic relief. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy (skin burn, muscle contracture complications) are commonly used and might also be effective.

In conclusion, MBC with isolated and easily approachable metastatic mass, total surgical excision is an alternative option for pain relief with improvement of life quality.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CK = cytokeratin, ER = estrogen receptor, Her-2/Neu = human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, MBC = metaplastic breast carcinoma, MMM = multiple muscle metastasis, MRM = modified radical mastectomy, PET/CT = positron emission tomography/computed tomography, PR = progesterone receptor.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Luini A, Aguilar M, Gatti G, et al. Metaplastic carcinoma of the breast, an unusual disease with worse prognosis: the experience of the European Institute of Oncology and review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007; 101:349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tse GM, Tan PH, Putti TC, et al. Metaplastic carcinoma of the breast: a clinicopathological review. J Clin Pathol 2006; 59:1079–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molina-Garrido MJ, Guillen-Ponce C. Muscle metastasis of carcinoma. Clin Transl Oncol 2011; 13:98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogiya A, Takahashi K, Sato M, et al. Metastatic breast carcinoma of the abdominal wall muscle: a case report. Breast Cancer 2015; 22:206–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim YW, Seo1 KJ, Lee SL, et al. Skeletal muscle metastasis from breast cancer: two case reports. J Breast Cancer 2013; 16:117–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doo SW, Kim WB, Kim BK, et al. Skeletal muscle metastasis from urothelial cell carcinoma. Korean J Urol 2012; 53:63–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]