Abstract

As a type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), vascular EDs (vEDS) is typified by a number of characteristic facial features (eg, large eyes, small chin, sunken cheeks, thin nose and lips, lobeless ears). However, vEDs does not typically display hypermobility of the large joints and skin hyperextensibility, which are features typical of the more common forms of EDS. Thus, colonic perforation or aneurysm rupture may be the first presentation of the disease. Because both complications are associated with a reduced life expectancy for individuals with this condition, an awareness of the clinical features of vEDS is important.

Here, we describe the treatment of vEDS lacking the characteristic facial attributes in a 24-year-old healthy man who presented to the emergency room with abdominal pain. Enhanced computed tomography revealed diverticula and perforation in the sigmoid colon. The lesion of the sigmoid colon perforation was removed, and Hartmann procedure was performed. During the surgery, the control of bleeding was required because of vascular fragility. Subsequent molecular and genetic analysis was performed based on the suspected diagnosis of vEDS. These analyses revealed reduced type III collagen synthesis in cultured skin fibroblasts and identified a previously undocumented mutation in the gene for a1 type III collagen, confirming the diagnosis of vEDS. After eliciting a detailed medical profile, we learned his mother had a history of extensive bruising since childhood and idiopathic hematothorax. Both were prescribed oral celiprolol. One year after admission, the patient was free of recurrent perforation.

This case illustrates an awareness of the clinical characteristics of vEDS and the family history is important because of the high mortality from this condition even in young people. Importantly, genetic assays could help in determining the surgical procedure and offer benefits to relatives since this condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner.

INTRODUCTION

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) is a heterogeneous group of heritable connective tissue disorders characterized by skin hyperextensibility, joint hypermobility, easy bruising, and tissue fragility. As 1 of 6 major types of EDs, vascular EDS (vEDS) is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner and is caused by COL3A1 mutations. The COL3A1 encoded protein is used to assemble larger molecules called type III collagens. Collagens provide structure and strength to connective tissue, which is mostly found in skin, blood vessels, and internal organs. vEDS is the most rare form of EDS (<5% of all EDS patients) but the most severe because of complications related to the vascular system, which can result in arterial rupture in young adults.1 Other major complications include uterine and intestinal rupture. Such complications are dramatic and unexpected, often presenting as sudden death, acute abdomen, retroperitoneal hemorrhage, uterine rupture at time of delivery, and/or shock. The average age for the first major arterial or gastrointestinal complication is 23 years.2 Therefore, establishing a correct diagnosis of vEDS is extremely important because the timing of diagnosis can influence prognosis.

Hypermobility of the large joints and skin hyperextensibility, characteristic of the more common EDS forms, are unusual in vEDS; thus, colonic perforation or aneurysm rupture may be the first presentation of the disease. Hence, vEDS in particular is associated with a reduced life expectancy. Thus, it is important to be aware of the clinical features of vEDS. vEDS is typified by a number of characteristic facial features (eg, large eyes, small chin, sunken cheeks, thin nose and lips, lobeless ears). Here, we describe vEDS lacking these characteristic facial attributes in a healthy man.

CASE PRESENTATION

In December 2012, a 24-year-old healthy Japanese man with abdominal pain was admitted to the emergency room. He had experienced subepithelial hematoma since childhood. After eliciting a detailed medical profile, we learned his mother had a history of extensive bruising since childhood, idiopathic hematothorax, and aortic dissection in youth. On admission, he showed stable vital signs but presented with thin translucent skin, extensive bruising, and toe-joint hypermobility. On examination, hypermobility of the small joints and subcutaneous hemorrhage were also detected (Figure 1). However, we did not observe hypertelorism, bifid uvula, or cleft palate, which are features of Loeys–Dietz syndrome. Palpation of the abdomen revealed tenderness, particularly in the left lower quadrant. Enhanced computed tomography revealed free air, diverticula, and perforation in the sigmoid colon. The lesion of the sigmoid colon perforation was removed, and Hartmann procedure was performed because of severe contamination in the emergency operation. During the surgery, the control of bleeding was required because of the vascular fragility of the patient. The patient had skin necrosis on day 12 but was discharged from the hospital 1 month post-operatively. He was asked to avoid hard labor since vEDS was suspected based on the major clinical criteria of thin skin with visible veins, colon rupture, and easy bruising. The characteristic facial features of this condition (eg, large eyes, small chin, sunken cheeks, thin nose and lips, lobeless ears) were not observed (Figure 2). Reversal of the Hartmann procedure was performed 4 months later. To confirm the diagnosis of vEDS, we performed genetic and molecular biological assays.

FIGURE 1.

Patient clinical features. Hyperextensibility of the finger joints and subcutaneous hemorrhage in the thenar region were observed.

FIGURE 2.

The patient showed none of the characteristic facial features (eg, large eyes, small chin, sunken cheeks, thin nose and lips, lobeless ears) of Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

DIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT

Cell Culture

Dermal fibroblasts were obtained from explants of a skin biopsy specimen taken from the upper arm of the patient and a sex- and age-matched control, after appropriate informed consent had been given. Dermal fibroblast cultures were established from the skin biopsy specimens using the outgrowth method.3 The cultures were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C. The study was approved by the ethical committee of Dokkyo Medical University, School of Medicine (Japan).

Analysis of Newly Synthesized Collagen

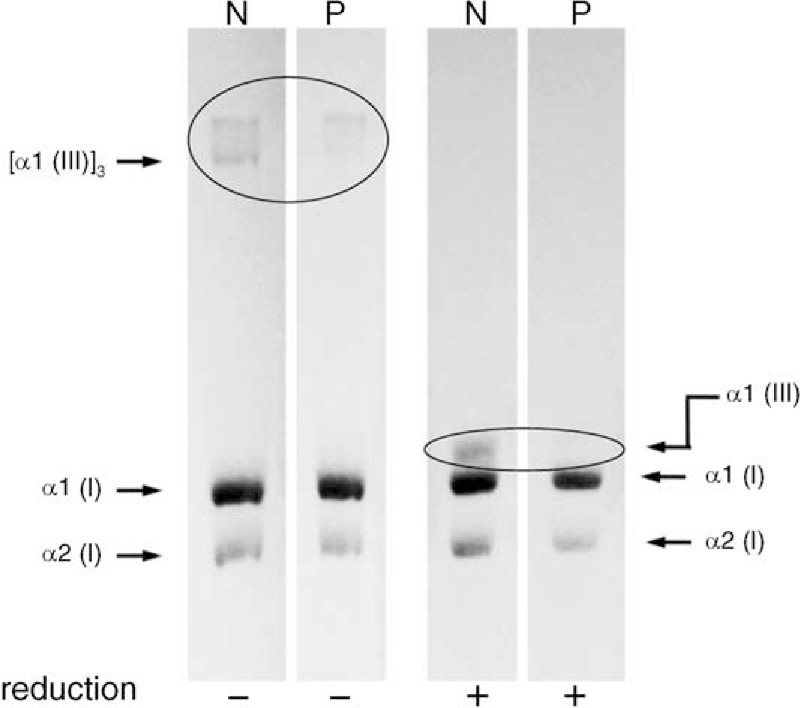

Collagen synthesis in the cultured dermal fibroblasts was assessed to determine whether the production of type III collagen was reduced in the patient. After the fibroblasts were cultured with [3H]proline, type III collagen and type I collagen [α1(I) + α2(I)] were isolated from the cultured dermal fibroblasts of the patient and sex- and age-matched control. Afterwards, they were separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and imaged using fluorography. Densitometric scans were then performed to measure the intensity of each band. The amount of the α1 chain of type III collagen secreted into the culture medium significantly decreased compared with that secreted from the control (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Production of type I or type III collagen in the patient's cultured fibroblasts. Cultured fibroblasts were pulse-labeled with [3H]proline in fresh medium, and the secreted proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under normal (−) or reducing (+) conditions. The synthesis of type I collagen in this patient was the same as in controls. However, the synthesis of type III collagen was reduced compared with the normal control values (inside circle). N, normal control; P, patient with Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

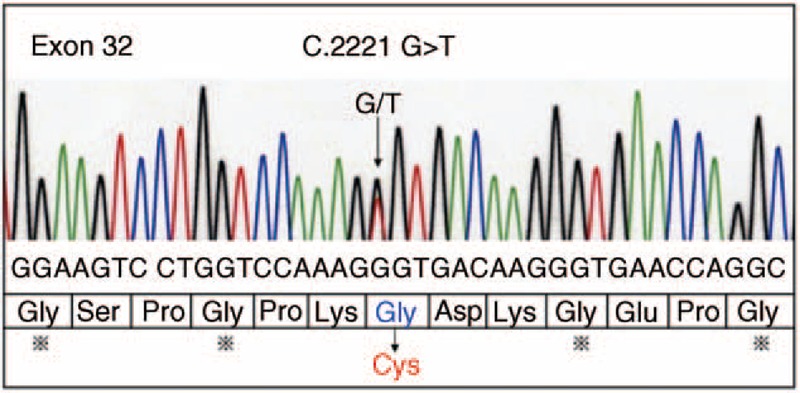

Analysis of Mutation

Based on the reduction in the α1 chain of type III collagen, we directly amplified and sequenced the COL3A1 gene from genomic DNA and detected a single base-pair change (G>T) predicted to convert a glycine to a cysteine in the encoded protein. Subsequently, total cellular ribonucleic acid was extracted from cultured dermal fibroblasts, and a complementary DNA of the COL3A1 gene was synthesized by priming with random hexamers. After the amplification products from a polymerase chain reaction were directly sequenced, we identified the same heterozygous mutation within exon 32 of the COL3A1 gene in proband c.2221 (G>T, Gly → Cys) (Figure 4). This mutation in the COL3A1 gene has not been previously reported.

FIGURE 4.

Sequence analyses of COL3A1 mutations. The arrow indicates the position of the point mutation. A heterozygous mutation was found within exon 32 of the COL3A1 gene in proband c.2221 (G>T, Gly → Cys).

Subsequently, the patient was diagnosed with vEDS based on reduced type III collagen synthesis and identification of a mutation in the COL3A1 gene. After confirmed diagnosis, the patient and mother were prescribed oral celiprolol (beta blocker). One year after admission, the patient was free of recurrent perforation.

DISCUSSION

We describe here the treatment of a patient with vEDS lacking the typical characteristic facial attributes of this condition and identified a previously undocumented mutation in the COL3A1 gene.

No standardized procedure for colonic perforation in vEDS patients has been developed.1 Here, we performed reversal of the Hartmann procedure, as in most previous cases. However, some cases have been managed with subtotal colectomy as the first-line management because colonic reperforation has been reported.4 Thus, conducting genetic assays to confirm diagnosis could be important for determining the operative technique or in saving relatives through treatment with beta blockers. In the present case, the patient and his mother were prescribed the β1-adrenoceptor-antagonist celiprolol. In a recent randomized multicenter trial, treatment with celiprolol was shown to result in a threefold decrease in the number of arterial events (rupture or dissection) during a mean follow-up of 47 months,5 and therefore might delay the need for invasive treatment. In the present case, the patient was free of recurrent perforation after 1-year admission.

The overall life expectancy of patients with vEDS is dramatically shortened, largely as a result of vascular rupture, with a median life span of 48 years (range, 6–73 years).2 In addition, the prognosis after treatment is still poor. In particular, previous reports have observed that the mortality rate ranged from 29 to 50%.1,6,7 Thus, close outpatient follow-up and appropriate guidance to the patient and family (eg, encouragement to contact the doctor when the patient suddenly notices unexplained pain) should be provided.8 In addition, the patient should carry a medical attention bracelet and papers noting information on the condition and blood group.8

Our case illustrates an awareness of the clinical characteristics of vEDS and the family history is important because of high mortality even in young people. The mutation in our case has not been previously documented and might explain the non-characteristic facial appearance. Thus, genetic assays could help in determining the surgical procedure and offer benefits to relatives, since this condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: cDNA = complementary deoxyribonucleic acid, DNA = deoxyribonucleic acid, EDS = Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, vEDS = vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest and received no specific grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergqvist D, Björck M, Wanhainen A. Treatment of vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a systematic review. Ann Surg 2013; 258:257–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pepin M, Schwarze U, Superti-Furga A, Byers PH. Clinical and genetic features of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV, the vascular type. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleischmajer R, Perlish JS, Krieg T, Timpl R. Variability in collagen and fibronectin synthesis by scleroderma fibroblasts in primary culture. J Invest Dermatol 1981; 76:400–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuchs JR, Fishman SJ. Management of spontaneous colonic perforation in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. J Pediatr Surg 2004; 39:e1–e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ong KT, Perdu J, De Backer J, et al. Effect of celiprolol on prevention of cardiovascular events in vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a prospective randomised, open, blinded-endpoints trial. Lancet 2010; 376:1476–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergqvist D. Ehlers-Danlos type IV syndrome. A review from a vascular surgical point of view. Eur J Surg 1996; 162:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oderich GS, Panneton JM, Bower TC, et al. The spectrum, management and clinical outcome of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV: a 30-year experience. J Vasc Surg 2005; 42:98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lum YW, Brooke BS, Black JH., 3rd Contemporary management of vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Curr Opin Cardiol 2011; 26:494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]