Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) affects over 180 million people worldwide and it's the leading cause of chronic liver diseases and hepatocellular carcinoma. HCV is classified into seven major genotypes and a series of subtypes. In general, HCV genotype 4 (HCV-4) is common in the Middle East and Africa, where it is responsible for more than 80% of HCV infections. Although HCV-4 is the cause of approximately 20% of the 180 million cases of chronic hepatitis C worldwide, it has not been a major subject of research yet. The aim of the current study is to survey the morbidities and disease complications among Egyptian population infected with HCV-4 using data mining advanced computing methods mainly and other complementary statistical analysis.

Six thousand six hundred sixty subjects, aged between 17 and 58 years old, from different Egyptian Governorates were screened for HCV infection by ELISA and qualitative PCR. HCV-positive patients were further investigated for the incidence of liver cirrhosis and esophageal varices. Obtained data were analyzed by data mining approach.

Among 6660 subjects enrolled in this survey, 1018 patients (15.28%) were HCV-positive. Proportion of infected-males was significantly higher than females; 61.6% versus 38.4% (P = 0.0052). Around two-third of infected-patients (635/1018; 62.4%) were presented with liver cirrhosis. Additionally, approximately half of the cirrhotic patients (301/635; 47.4%) showed degrees of large esophageal varices (LEVs), with higher variceal grade observed in males. Age for esophageal variceal development was 47 ± 1. Data mining analysis yielded esophageal wall thickness (>6.5 mm), determined by conventional U/S, as the only independent predictor for esophageal varices.

This study emphasizes the high prevalence of HCV infection among Egyptian population, in particular among males. Egyptians with HCV-4 infection are at a higher risk to develop cirrhotic liver and esophageal varices. Data mining, a new analytic technique in medical field, shed light in this study on the clinical importance of esophageal wall thickness as a useful predictor for risky esophageal varices using decision tree algorithm.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) has been identified by the WHO as a major health problem as it is a major cause of chronic liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma, deaths from liver disease, and is the most common indicator for liver transplantation worldwide.1 HCV exhibits a high degree of genetic diversity; it is classified into 7 different genotypes and more than 60 subtypes.2,3 Each genotype has its distinct geographical distribution, that is, HCV-1 and HCV-2 are the most common genotype in USA, Europe, and Japan. HCV-3 is predominant in Asia while HCV-5 and HCV-6 are mostly confined to Southeast Asia and South Africa. HCV-4 is the predominant genotype in the Middle East and North Africa with exception to Algeria (HCV-1b).4 Egypt has the highest prevalence of HCV infection worldwide (>10% of the general population; HCV-4), while China has the largest number of HCV-infected people (29.8 million).5 HCV infection can cause acute and chronic hepatitis. Most cases of acute hepatitis C are anicteric and asymptomatic, with fewer than 25% are clinically apparent, whereas, fulminant hepatitis C is rare. Nevertheless, the long-term liability of acute hepatitis C is significant due to the high rate of chronic infection. Approximately 20% to 30% of those chronically infected will develop cirrhosis, and a proportion of those patients will develop hepatocellular carcinoma.6

In Egypt, treatment of chronic HCV infection with pegylated interferon alpha and ribavirin represents the gold standard for HCV management as the treatment with Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi™), an oral nucleotide analog inhibitor of the HCV NS5B polymerase enzyme, an enzyme that plays an essential role in HCV replication, is not well established yet.7 Various HCV genotypes exhibit different patterns of treatment response to the peginterferon and weight-based ribavirin therapy; thus dosage, duration of treatment and therapeutic approach has to be tailored according to each HCV genotype. Sustained virologic response is the required end point of treatment and its rate is considerably high in patients infected with HCV genotypes 2 and 3 (∼80%), however, sustained virologic response rates are lower in those patients infected with genotypes 1 and 4 (∼50%).3

Advances in medical information technology resulted in enormous warehouses of data that are overwhelming and sparse. Data mining are the art of extracting valuable information and finding new correlations from analyzing massive amount of data. Analysis of this information can shed light on significant factors that contribute to each disease condition.8 In this study, we aim to survey the HCV-4 infection in Egypt and investigate the risky complications resulting from HCV infection, particularly cirrhosis and esophageal varices. Additionally, we will use data mining to determine the risk factors for the variceal development.

METHODS

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethic Committee in Al Azhar University Hospitals. A written informed consent was obtained from patients enrolled in this study.

Patients

A total of 6660 subjects, 3836 males (57.6%), and 2824 females (42.4%), were prospectively examined for HCV infection by ELISA and quantitative PCR test, between January 2004 and May 2013 in several medical centers in urban and rural areas across Egypt. HCV-positive patients underwent further investigations for HCV-related complications as cirrhosis and esophageal varices. Patients presented in variable degrees of hepatitis, ranging from mild hepatitis activity to decompensated cirrhosis. Patients positive to HCV Ab and negative by Qualitative PCR test were excluded from the study (562/6660 patients, 8.4%). Patients co-infected with HBV and HCV were also excluded (51/6660 patients, 0.7%). Only HCV infection was included.

On the other hand, patients with portal hypertension induced-esophageal varices were included in our internship program to evaluate esophageal variceal degrees using non-invasive Two dimensional ultrasound (2D U/S) application. All data were collected prior to interferon-based therapy including patients who were followed up for esophageal varices.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical differences in various parameters of male and female groups were determined by Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

Data Mining Analysis

Data mining analysis is the process of examining large amount of data by computer to create an algorithm. Conventional statistics is used to examine a certain hypothesis. In this context, data mining is superior as it makes computerized algorithms using both Naïve Baÿes and decision tree methods; 10 folds Naïve Baÿes used was applied.

The descriptive Rapid I models were generated to decide the most significant independent variable in each stage of predicting dependent variables. Rapid Miner, Rapid I, version 4.6, Berlin, Germany was used. Sensitivity was 97%, specificity was 93%, and the overall accuracy was 95%. Internal validation was performed using the test mode: 10 folds cross validation using Naïve Baÿes application, which is generally applied to predict the performance of a model on a validation set using computation in place of mathematical analysis.

RESULTS

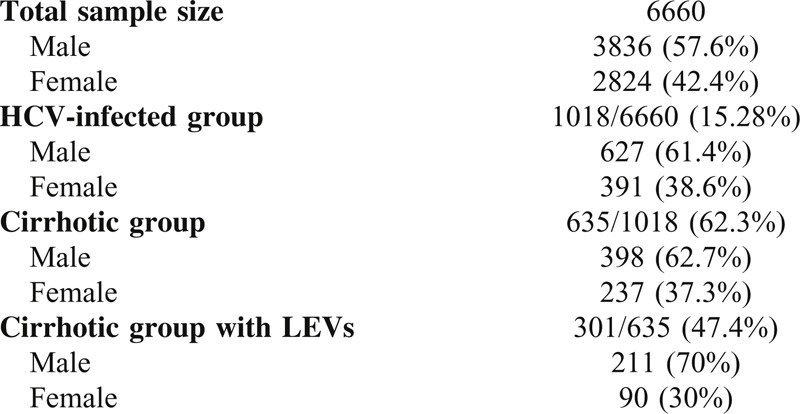

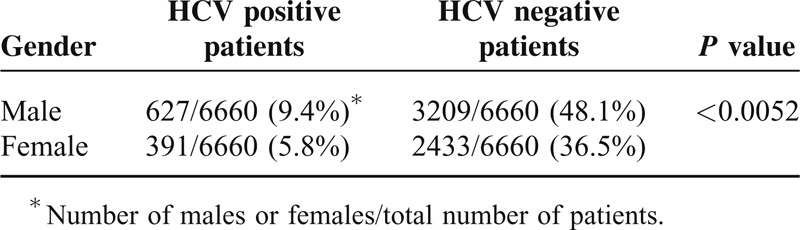

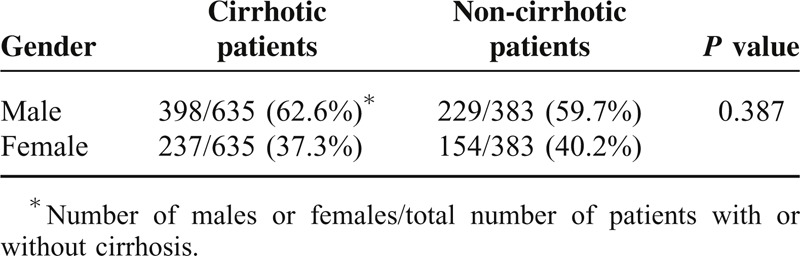

Screening of 6660 subjects, 3836 males (57.6%), and 2824 females (42.4%), from both urban and rural areas for HCV infection yielded 1018 (15.28%) HCV-positive patients by ELISA and PCR Table 1. Additionally, we observed that 8.4% of the examined subjects (562/6660 patient; 546 males and 16 females) were positive to anti-HCV Ab by ELISA but negative for HCV-RNA by PCR; and hence those were excluded from this study. No patients were found to be positive to HCV-RNA and negative to anti-HCV Ab. Among the HCV-positive patients, 627 males (61.4%) and 391 females (38.6%), the rate of infection was significantly higher in males than that in females; P = 0.0052 (Table 2). The average age for patients included in the study was 40 years old ranging between 17 and 58 years old. Additionally, among the 1018 HCV-patients, 635 patients 62.3% (398 males and 237 female; 62.7% and 37.3%, respectively) presented with cirrhotic-portal hypertension. The other 383 patients (37.62%) did not show any cirrhotic manifestations, Table 3.

TABLE 1.

Showing the Survey Study of Egyptian Patients Infected With HCV-4; (LEVs); Large Esophageal Varices

TABLE 2.

Correlation Between the Patient Sex and HCV Infection in Egypt

TABLE 3.

Correlation Between the Patient Sex and Liver Cirrhosis

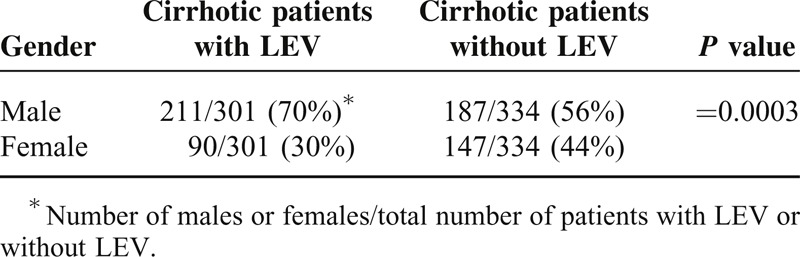

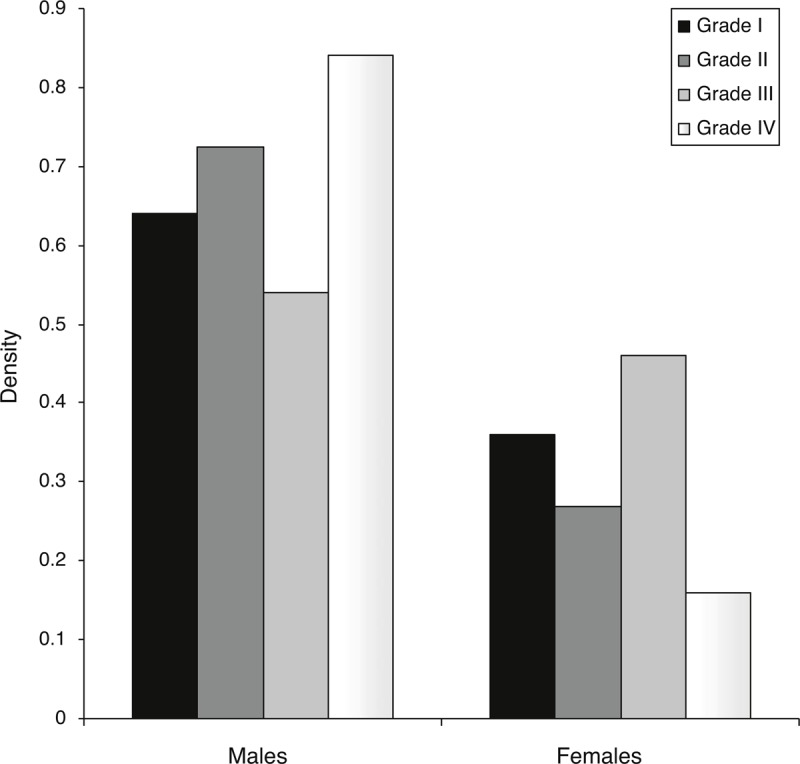

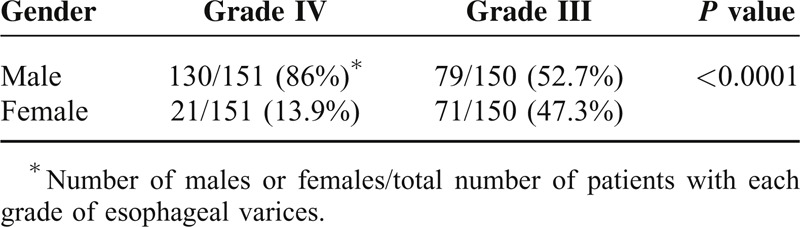

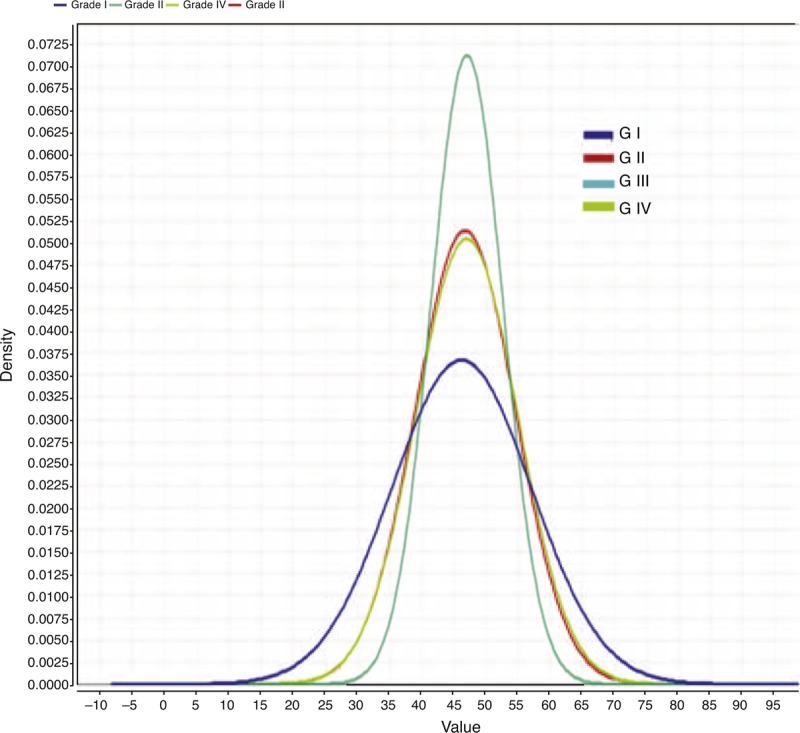

Using 2D U/S, we screened the esophageal wall thickness in the cirrhotic patients. Patients with esophageal wall thicknesses >6.5 mm in 2D U/S showed large esophageal varices; Grades III or IV varices, as determined by upper endoscopy. Whereas, patients with esophageal wall thicknesses <4.0 mm showed normal endoscopic finding; no varices or other esophageal abnormalities were observed. Among the cirrhotic patients, 301/635 patients (47.4%), 211 males (70%), and 90 females (30%), had large esophageal varices (LEV); Grades III and IV varices, with the incidence of LEV was significantly higher in males than females; P = 0.0003 (Table 4). Grade IV varices were the predominant finding in male patients followed by Grades II and I degrees, while Grade III varices were the predominant varices in female patients followed by Grades I and II, Figure 1. Males had a significantly higher percentage of Grade IV varices versus females, P < 0.0001, Table 5. Age for esophageal variceal development was 47 ± 1 years old, Figure 2.

TABLE 4.

Correlation Between the Patient Sex and Esophageal Varices; LEV: Large Esophageal Varices

FIGURE 1.

Correlation between sex and variceal degree. Y axis represents the density of each parameter by data mining analysis. The sum of each variceal degree for both males and females equals 1.

TABLE 5.

Correlation Between the Patient Sex and the Grade of Esophageal Varices

FIGURE 2.

Age group according to different variceal degrees. Middle of the 4th decade is the peak of varices development. X axis represents the patient age while Y axis represents the density of each time point.

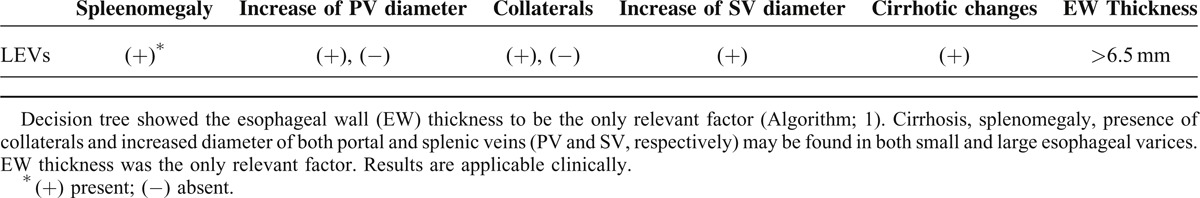

Decision tree showed a strong association between esophageal wall thicknesses and corresponding variceal degrees in proportional character. The median wall thicknesses for Grade I varices was 4.75 mm, for Grade II varices was 6.25 mm, for Grade III varices was 7.25 mm, and for Grade IV varices was 8.50 mm. The prediction model in data mining decision tree algorithm selected the increased esophageal wall thickness as the only predictive factor for the presence of esophageal varices (Table 6). The presence of other factors as cirrhosis, splenomegaly, presence of collaterals and increased diameter of both portal and splenic veins was not specific to the development of the LEV.

TABLE 6.

Correlation Between Different Factors Associated With Large Esophageal Varices (LEVs)

DISCUSSION

Globally, it is estimated that HCV-4 causes approximately 20% of the 180 million cases of chronic hepatitis C in the world.9,10 In the present study, we examined 6660 subjects randomly selected from Egypt in both urban and rural areas. The HCV infection was approximately 15.28% and male infection rate was significantly higher than females (P = 0.0052). Additionally, 562/6660 patients (8.4%) were positive for anti-HCV antibodies and negative for HCV-RNA. Those patients might have been infected with HCV at some point but recovered after acute infection. Several studies reported the spontaneous viral clearance in acute HCV infection through innate immunity response.11 Alternatively, they might be patients with old bilharzial infection in a form of antibody cross-reactivity.12 Among the HCV-4 group (1018 patients), 635 patients (62.3%) had the cirrhotic-portal hypertension criteria diagnosed clinically, sonographically, or by other investigations as biopsy, upper endoscopy, CT, and MRI. Criteria as the presence of liver coarseness, attenuation of hepatic veins, irregular borders, shrunken size, hypertrophic caudate lobe, and splenomegaly-related cirrhosis in sonographic pictures represent advanced cirrhotic picture. Although, the cirrhotic group comprised of 62.7% males and 37.3% female but there was no statistical difference between the patient sex and the development of cirrhosis (P = 0.38). However, males were more likely to develop esophageal varices (P = 0.0003), specifically Grade IV varices (P < 0.0001).

The HCV prevalence reported in our study is in agreement with previous reports studying HCV infection in the general population across Egypt.13–15 The origin of HCV epidemic in Egypt has been attributed to mass campaigns of parental anti-bilharzial therapy between 60s and 80s decades, blood transfusion, injections, circumcision, dental procedures, surgeries, and instrumental delivery.13 Additionally, we observed a higher prevalence of HCV in males (62.7%). Farming related-water activities is the one of the primary occupations for Egyptians males in rural areas across Egypt. This might explain the higher exposure of males to schistosomal infection and parental anti-schistosmiasis therapy during 70s and 80s decades, and the higher incidence of unsafe medical-practice related HCV transmission as needle injections among males.13,16 Alternatively, it could be explained by hormonal factors that enable females to clear HCV in the acute stage as estrogen was previously reported to inhibit the production of HCV infectious particles in cell culture system.17 Moreover, it was recently reported that the presence of certain single nucleotide polymorphisms of the estrogen receptor α can enable females to attain either spontenous clearance or or persistent infection of HCV.18 Even after HCV infection, an additional protective effect for estrogen during the progression of the disease was also suggested. Several studies showed that chronic HCV infection develop more rapidly in men than in women and disease complications like cirrhosis are more pronounced in men and post-menopausal women.19,20 Estrogen inhibits the reactive oxygen species production processes, the activation of hepatic stellate cells and early apoptosis of hepatocytes.21 This might slow down the progression of hepatic fibrosis in females. In the same context, we observed a higher ratio of cirrhotic males to females (1.9:1) in this study.

To date, available HCV treatment in Egypt is a combination of Peg. interferon and weight-based ribavirin therapy and they result in sustained virologic response rates of only 40% to 50% in patients with chronic HCV-4.22,23 Most (>90%) of the HCV isolates found in Egypt, belong to genotype 4. Given the side effects and the economic burden of treatment, proper selection of patients undergoing therapy is valuable. Several host and virological factors can be used to predict the treatment response of HCV-4 and hence aid in proper patient selection. From the virological factors are the NS5A mutations specifically a region named interferon ribavirin resistance determining region (IRRDR) in HCV-4; mutations in IRRDR>4 were correlated with a positive treatment response.24 Host factors as the single nucleotide polymorphisms near the IL28 region were correlated with the treatment response. Patients with the favorable genotype (CC at the rs12979860 polymorphic site) were more likely to respond to the therapy.25,26 Another determining factor was the cirrhotic condition of the liver. Cirrhosis progression and co-infection with schistosomiasis decrease the patient's possibility to achieve sustained viral response.27

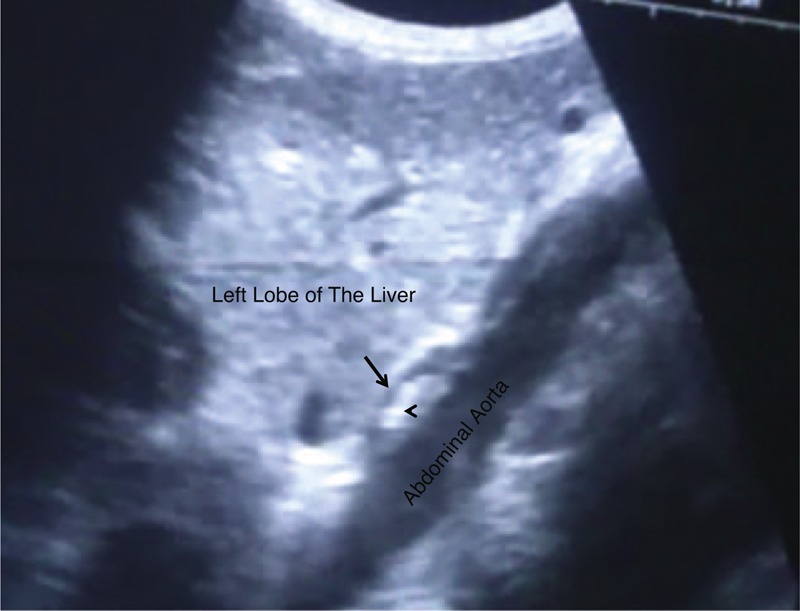

Abdominal US can detect liver cirrhosis and provide useful data for the presence of portal hypertension and esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. The use of 2D U/S to detect risky esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients was recently proposed.28,29 The intra-abdominal portion of esophagus could be detected using 2D U/S, Figure 3. Esophageal wall thicknesses >6.5 mm were correlated with large esophageal varices, while esophageal wall thicknesses <4 mm was correlated with normal endoscopic finding. Decision tree showed a strong association between esophageal wall thicknesses and corresponding variceal degrees. According to the current study, among patients presented with cirrhosis, 301/635 patient (47.4%) had large esophageal varices; Grades III and IV varices, with or without gastric varices, and those should be candidate for prophylactic measures. Prophylactic band ligation with pharmacotherapy in the form of non-selective beta blocker (40 mg in 2 divided doses and Isosorbide-mononitrate 20–25 mg/daily) are very effective as primary or secondary prophylaxis in those presented with esophageal varices. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is a common medical condition that results in high patient morbidity and medical care costs. Upper endoscopy is the diagnostic modality of choice for acute upper GI bleeding in patients presenting with hematemesis and /or melena due to portal hypertension-induced cirrhosis, Grade IV varices were the predominant finding in male patients followed by Grades II and I degrees, whereas, Grade III varices were the predominant varices in female patients followed by Grades I and II, Figure 1, Table 5. Age for esophageal variceal development is 47 ± 1 years old, Figure 2.

FIGURE 3.

Intra-abdominal portion of esophagus, easy demonstrated between left lobe of the liver and aorta. Anterior wall; hypoechoic (arrow). The hyperechoic lumen (arrow head).

It was previously reported that patients co-infected with HCV and schistosoma had an increased incidence of viral persistence, accelerated fibrosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma as well as a much higher mortality rate.30 Therefore, it plausible to speculate that, the degrees of varices correspond to the long duration of viral infection, older age, and co-infection with schistosomiasis. In this study, 62 patients co-infected with HCV and a previous schistosomal infection as confirmed by thick peri-portal fibrosis in an abdominal U/S screening and past history of schistosomal infection; however, we did not test for the anti-schistosomal antibody in all patients. It is worth mentioning that those 62 patients were among the advanced varices group.

Umbilical hernias pose a management dilemma in patients with cirrhosis in Egypt, especially those with old schistosomiasis, since hernias often develop in patients with severe liver disease and ascites who are at high risk of complications with surgical repair.31–33 We attempted successful management using a variety of minimally invasive surgical techniques according to evidence-based studies/reports. However, clinical experience has tempered our enthusiasm for elective surgical repair for every situation according to each patient's condition. According to our strategy for those waiting for liver transplantation, Egyptian surgeons prefer to repair hernias at the time of transplantation and not before because many have observed high postoperative morbidity and mortality when repair was performed before the transplantation.34–37

The decision tree; one of data mining computing algorithm, tries to mimic the human brain connecting attributes to each other, aims to compare these information-related attributes to one another, finally looks for the strongest connections. The network could apply the suitable required model to score the applicable data in order to make predictions in the applied medicine.38 Analyzing our data by RapidMiner ver.4.6 sheds light on the significant important factors for each disease condition.39–41 In order to predict the independent factors associated with esophageal varices, we analyzed the following factors: cirrhosis, esophageal wall thickness, splenomegaly, the presence of collaterals and increased diameter of both portal and splenic veins, and a decision tree was created. A descriptive model was generated using decision tree algorithm identified the increased esophageal wall thickness as the only independent predictor for LEVs.

In conclusion, the main finding of this study is the verification of the severity of HCV infection in Egypt (15.28%). HCV-4 appears to affect males more than females and its complications are more pronounced in males rather than females. Since, HCV-4 shows a higher resistance against Interferon therapy3 and the progression to cirrhosis appear to be faster in HCV-4 especially when co-infected with schistosomiasis30 and given the long incubation period of HCV and the high infection rate in Egypt, so peak morbidity and mortality is yet to come. Therefore, Egypt faces TWO key problems, prevention of further infection and providing efficient health care for those already infected. Finally, using data mining in applied clinical medicine is useful to predict factors leading to disease progression. The information obtained from data mining should be studied efficiently in order to understand how efficacy those data influence the disease progression or regression in a medical view.

FUTURE RECOMMENDATION

This study surveyed that the HCV infection rate in Egypt from 2004 till 2013 in the era of interferon/ribavirin based therapy. It will be interesting to study the change in the HCV infection rates in Egypt after the start of the new oral therapy (Sofosbuvir, Daclatasivir and combination of both Sofosbuvir and Ledipasvir).

We recommend using viral factors as IRRDR to predict the treatment outcome of the new oral therapy in patients who experienced previous Interferon therapy and those who did not.

Pre-emptive oral therapy (Sovaldi®, Daclinza®, Harvoni®) should be considered early for those with HCV-4 experienced liver transplantation, because all patients showed viral graft invasion post liver transplant operation with considerable percentage of graft failure early or late post operative.

LIMITATION OF THE STUDY

The current study shed light on HCV-4 infection only in Egypt.

We recommend a second study involving more patients with a greater age range especially after expected success of the new oral therapy.

Our research, clinical and even radiological experience played the major role in all information mentioned in the study; hence, other researches may show different results. Our results must be confirmed using more evidence-based criteria especially when included all Egyptian Governments after all-oral free therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Koichi Tanaka the Fujiyama of LDLT worldwide and Dr Kenji Uryuhara, Dr Takako Yamada for valuable advice and support during studying HCV advances and LDLT innovations when the corresponding author was studying in Japan, hence without them, this study would not have been possible. They also wish to thank Dr Ahmed El-shamy (Mount Sinai, School of Medicine, New York, USA) for valuable discussion.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: Ab = antibody, EW = esophageal wall, HBV = hepatitis B virus, HCV = hepatitis C virus, IRRDR = interferon ribavirin resistance determining region, LEV = large esophageal varices, 2D US = two dimensional ultrasound.

The study was carried out in Egypt. Ethical committee approved the current study and each patient approved with a written consent.

Author contributions: Abd Elrazek M. Ali Abd Elrazek, planning and conducting the study, collecting and interpreting data, examined the patients with his team, drafting the manuscript, performed the data mining statistical analysis, he approved the final draft submitted; Shymaa E. Bilasy, analysis, writing, and revising the manuscript, she approved the final draft; Abduh El banna, conducting the study, he approved the final draft submitted; Abd Elhalim El sherif, revised the study, he approved the final draft submitted.

Abd Elrazek M. Ali Abd Elrazek and Shymaa E. Bilasy contributed equally to this work.

The authors have no funding grants and no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology 2013; 57:1333–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simmonds P. The origin and evolution of hepatitis viruses in humans. J Gen Virol 2001; 82:693–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Shamy A, Hotta H. Impact of hepatitis C virus heterogeneity on interferon sensitivity: an overview. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20:7555–7569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rouabhia S, Sadelaoud M, Chaabna-Mokrane K, et al. Hepatitis C virus genotypes in north eastern Algeria: a retrospective study. World J Hepatol 2013; 5:393–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Dore GJ. Epidemiology and natural history of HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 10:553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Zayadi AR, Badran HM, Barakat EM, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Egypt: a single center study over a decade. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11:5193–5198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asselah T. Sofosbuvir for the treatment of hepatitis C virus. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2014; 15:121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu S, Jin B, Cowart LA, Lu X. From data towards knowledge: revealing the architecture of signaling systems by unifying knowledge mining and data mining of systematic perturbation data. PLoS ONE 2013; 8:e61134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heintges T, Wands JR. Hepatitis C virus: epidemiology and transmission. Hepatology 1997; 26:521–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swain MG, Lai MY, Shiffman ML, et al. A sustained virologic response is durable in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin. Gastroenterology 2010; 139:1593–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Micallef JM, Kaldor JM, Dore GJ. Spontaneous viral clearance following acute hepatitis C infection: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Viral Hepat 2006; 13:34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agha S, El-Mashad N, El-Malky M, et al. Prevalence of low positive anti-HCV antibodies in blood donors: schistosoma mansoni co-infection and possible role of autoantibodies. Microbiol Immunol 2006; 50:447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guerra J, Garenne M, Mohamed MK, Fontante A. HCV burden of infection in Egypt: results from a nationwide survey. J Viral Hepat 2012; 19:560–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohamed MK. Epidemiology of HCV in Egypt 2004. Afro-Arab Liver J 2004; 13:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohamoud YA, Mumtaz GR, Riome S, et al. The epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in Egypt: a systematic review and data synthesis. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13:288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Habib M, Mohamed MK, Abdel-Aziz F, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in a community in the Nile Delta: risk factors for seropositivity. Hepatology 2001; 13:248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayashida K, Shoji I, Deng L, et al. 17β-Estradiol inhibits the production of infectious particles of hepatitis C virus. Microbiol Immunol 2010; 54:684–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang S, Yue M, Wang J, et al. Association of genetic variants in estrogen receptor α with HCV infection susceptibility and viral clearance in a high-risk Chinese population. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2014; 33:999–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimizu I. Impact of oestrogens on the progression of liver disease. Liver Int 2003; 23:63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poynard T, Ratziu V, Charlotte F, et al. Rates and risk factors of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis c. J Hepatol 2001; 34:730–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimizu I, Ito S. Protection of estrogens against the progression of chronic liver disease. Hepatol Res 2007; 37:239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramachandran P, Fraser A, Agarwal K, et al. UK consensus guidelines for the use of the protease inhibitors boceprevir and telaprevir in genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C infected patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 35:647–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghany MG, Nelson DR, Strader DB, et al. An update on treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2011; 54:1433–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Shamy A, Shoji I, El-Akel W, et al. NS5A sequence heterogeneity of hepatitis C virus genotype 4a predicts clinical outcome of pegylated-interferon-ribavirin therapy in Egyptian patients. J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50:3886–3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asselah T, De Muynck S, Broët P, et al. IL28B polymorphism is associated with treatment response in patients with genotype 4 chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2012; 56:527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Nicola S, Aghemo A, Rumi MG, et al. Interleukin 28B polymorphism predicts pegylated interferon plus ribavirin treatment outcome in chronic hepatitis C genotype 4. Hepatology 2012; 55:336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdel-Rahman M, El-Sayed M, El Raziky M, et al. Coinfection with hepatitis C virus and schistosomiasis: fibrosis and treatment response. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19:2691–2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Razek Abd El, Mahfouz Hamdy M, Afifi M, et al. Detection of risky esophageal varices by two-dimensional ultrasound: when to perform endoscopy. Am J Med Sci 2014; 347:28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ali Abd Elrazek AEM, Abd Elazeem K, El sherif AEA, El sherbiny S, Abdel-aal UM, Bilasy SE. Screening esophagus during routine U/S: medical and cost benefits. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014, [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamal S, Madwar M, Bianchi L, et al. Clinical, virological and histopathological features: long-term follow-up in patients with chronic hepatitis C co-infected with S. mansoni. Liver 2000; 20:281–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carbonell AM, Wolfe LG, DeMaria EJ. Poor outcomes in cirrhosis-associated hernia repair: a nationwide cohort study of 32,033 patients. Hernia 2005; 9:353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marsman HA, Heisterkamp J, Halm JA, et al. Management in patients with liver cirrhosis and an umbilical hernia. Surgery 2007; 142:372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Triantos CK, Kehagias I, Nikolopoulou V, Burroughs AK. Surgical repair of umbilical hernias in cirrhosis with ascites. Am J Med Sci 2011; 341:222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarit C, Eliezer A, Mizrahi S. Minimally invasive repair of recurrent strangulated umbilical hernia in cirrhotic patient with refractory ascites. Liver Transplant 2003; 9:621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melcher ML, Lobato RL, Wren SM. A novel technique to treat ruptured umbilical hernias in patients with liver cirrhosis and severe ascites. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2003; 13:331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Senzolo M, Cholongitas E, Tibballs J, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of ascites and hepatorenal syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 18:1143–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Belli G, D’Agostino A, Fantini C, et al. Laparoscopic incisional and umbilical hernia repair in cirrhotic patients. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2006; 16:330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.North M. Data mining for the masses. USA Global Text Project, Aug; 2012; ISBN 0615684378, 9780615684376. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abd Elrazek AE, Mahfouz HM, Metwally A, El-Shamy A. Mortality prediction of non-alcoholic patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding using data mining. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 26:187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aly abd Elrazek Abd Elrazek M, Mahfouz HM. Prediction analysis of esophageal variceal degrees using data mining: is validated in clinical medicine? Global J Comput Sci Technol 2013; 13:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elbanna A, Elrazek A. Is advanced statistical computing technology a clue in applied medicine? A study using data mining as a predictor technology in gastroenterology & bariatric surgery; novel elbanna operations. Global J Comput Sci Technol 2013; 13:31–37. [Google Scholar]