Abstract

Ultrasound examination is becoming more and more common in patients with rheumatoid diseases. Above all, it enables the assessment of articular soft tissues and constitutes a non-invasive examination. In a rheumatologist's everyday practice, it is conducted at the stage of initial diagnosis as well as to monitor the treatment and to confirm the remission if the clinical picture is ambiguous. The first sign of arthritis (including rheumatoid arthritis) that is visible on ultrasound examination is the thickening of the synovial membrane of the joint cavities, tendon sheaths or bursae. It is frequently accompanied by the exudate in the joint, sheath or bursa. In a subsequent stage, in Doppler examination, enhanced vascularization of the synovial membrane is observed. Sometimes, the inflammatory process of the tendon sheaths also affects the tendons, which might lead to their damage. Moreover, ultrasound examination also reveals erosions and inflammatory cysts (geodes) which attest to the advancement of the disease. A dynamic ultrasound examination enables to diagnose the capsule-ligamentous contracture of the interphalangeal joints, which occurs due to the lack of rehabilitation that should begin at the moment of the commencement of the inflammation. The ultrasound image does not allow for the differentiation between various rheumatoid entities, including those encompassing the joints in the hand, wrist. The observed changes, i.e. thickening of the synovial membrane, hyperemia, effusions, erosions or tendon damage, may accompany various rheumatoid entities. The purpose of the ultrasound examination is to recognize these irregularities, determine their localization and advancement and, finally, to monitor the course of treatment. Furthermore, ultrasound scan enables to assess the joints and tendons in a dynamic examination in relation to local ailments of the patient as well as to monitor the biopsy, aspiration and medicine administration. Sonography is used for a US-guided administration of radioisotope substances for synoviorthesis.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatoid hand, sonography, synovitis, tenosynovitis, bursitis

Abstract

Badanie ultrasonograficzne jest coraz powszechniej wykonywane u pacjentów z chorobami reumatycznymi. Umożliwia ocenę przede wszystkim tkanek miękkich stawów. Ma nieinwazyjny charakter. W codziennej praktyce reumatologa przeprowadza się je na etapie diagnozy, monitorowania leczenia oraz w celu potwierdzenia remisji, jeżeli obraz kliniczny nie jest jednoznaczny. Pierwszym objawem zapalenia stawów (w tym reumatoidalnego zapalenia stawów) widocznym w badaniu ultrasonograficznym jest pogrubienie błony maziowej jam stawów, pochewek lub kaletek. Często towarzyszy mu wysięk w stawie, pochewce lub w kaletce. W kolejnym etapie w badaniu dopplerowskim obserwowane jest wzmożone unaczynienie błony maziowej. Niekiedy proces zapalny pochewek ścięgnistych obejmuje także ścięgna, co może prowadzić do ich uszkodzenia. W badaniu ultrasonograficznym widoczne są ponadto nadżerki i geody, będące dowodem zaawansowania choroby. Dynamiczne badanie ultrasonograficzne pozwala na rozpoznanie przykurczu struktur torebkowo-więzadłowych stawów międzypaliczkowych, najczęściej z powodu braku rehabilitacji, która powinna być rozpoczęta w momencie wystąpienia zapalenia stawu. Obraz ultrasonograficzny nie pozwala na różnicowanie poszczególnych jednostek reumatycznych, w tym obejmujących stawy ręki, także nadgarstka. Obserwowane zmiany, tj. pogrubienie błony maziowej, jej przekrwienie, wysięki, nadżerki, uszkodzenia ścięgien, towarzyszą wielu jednostkom reumatycznym. Celem badania ultrasonograficznego jest rozpoznanie tych nieprawidłowości, określenie ich lokalizacji i zaawansowania, wreszcie monitorowanie w trakcie leczenia. Badanie ultrasonograficzne umożliwia ponadto ocenę stawów i ścięgien w badaniu dynamicznym, w konfrontacji z dolegliwościami punktowymi pacjenta, monitorowanie biopsji, aspiracji, podawania leków. Pod kontrolą ultrasonografii podawane są do stawów radioizotopy w celu synowiortezy radioizotopowej.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common rheumatoid condition and affects approximately 2% of adult population. The onset of the disease usually takes place between the 45th and 55th year of age and, if not diagnosed early, it rapidly leads to permanent deformities of the motor organs. The most frequently affected anatomic area in the course of RA is the hand (anatomically, the hand is made up of the wrist, metacarpus and fingers). The term rheumatoid hand denotes the hand deformed in the course of RA, which results from: the injury to the ligamentous complex of the midcarpal, carpometacarpal, metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints; deformity of the bone bases that compose the joints as well as post-inflammatory lesions in the tendon sheaths and tendons (fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Rheumatoid hand in the patient with a long-term RA

At present, due to the advancement of knowledge concerning the pathogenesis of RA and the development of diagnostic methods, including imaging techniques such as ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), controlling the ailments and symptoms of the disease are not the only main aims of rheumatoid arthritis management. RA is diagnosed early, which allows for rapid implementation of the treatment preventing the advancement of the disease into its irreversible form that results in hand deformities(1, 2). Thus, contemporary treatment is not merely symptomatic, but also partially causal since, thanks to the knowledge of the pathogenesis, it is possible to inhibit certain pathogenetic mechanisms, which hinders RA advancement. The position of individual imaging examinations in the diagnostic algorithm of RA also changes. Radiological examinations of bones, which for many years constituted the only imaging modality in RA diagnostics, reveal advanced, irreversible lesions such as erosions, inflammatory cysts (geodes) and joint deformities. However, early inflammatory changes are visible in US and MRI(1–4). Although they are non-specific and initially discrete, their detection allows for the commencement of treatment in an early stage of the disease. As a result, we will observe the classical image of the rheumatoid hand, deformed by the disease, more and more rarely.

Ultrasound in the diagnosis of rheumatoid hand

US examination is commonly performed in rheumatoid patients primarily for the purposes of evaluating the soft tissues of the joints. The anatomy of the hand, including the wrist, is complex(5). Rheumatoid arthritis affects the sites in which the synovial membrane may be found (articular cavities, bursae and sheaths) and therefore, all these sites are subject to a thorough evaluation. Moreover, one should remember about the limited volume of the osteofibrous carpal tunnel in which all pathologies, both inflammatory (synovitis of the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints as well as tenosynovitis of the flexor tendons) and non-inflammatory ones (e.g. muscle anomalies, osseous lesions), will predispose to the median nerve compression – a neuropathy which does not necessarily require retinacular incision.

In a rheumatologist's everyday practice, US examination is conducted at the stage of diagnosis as well as to monitor the treatment and to confirm the remission if the clinical picture is ambiguous. At the stage of diagnosis, US examination aims at visualizing or excluding inflammatory lesions and in the case of their presence – determining their localization and intensity (degree of activity). Finally, although radiography is the main method in this area, US examination enables to detect erosions which attest to the advancement of the disease and completely change the prognosis. During US examination the following are assessed: articular cavities (in search for the signs of synovitis and effusions), bone outlines (in terms of geodes and erosions), tendons and their sheaths (searching for the signs of synovitis, effusion and tendon damage) and bursae (in the hand below the second compartment of the extensors; in search for synovitis and effusion).

The synovial membrane lines the inner surface of the articular capsule, tendon sheaths and bursae. In normal conditions, in healthy persons, it is not visible on US scans. In the course of RA, however, the subsequent stages of its evolution, which correspond to the lesions presented in our previous articles, are observed(1, 2). The hyperplasia of the intimal layer and inflammatory edema of the subintimal layer are visible in the form of synovial thickening (figs. 2, 3). A coexistent joint effusion is frequently observed and, contrary to the thickened synovium, it will undergo decompression when pressure is applied with the transducer(1, 2, 6). The effusion in the articular cavities, sheaths and bursae results from the malfunction of the synovial membrane which is affected by inflammation. The aim of the US examination is not to measure its thickness, but to determine, by means of the probe-induced compression, whether it is of low, medium or high pressure. Moreover, enhanced vascularization in the synovium, observed in power Doppler ultrasound examination (PDUS), attests to the process of neoangiogenesis (figs. 4, 5). During US examination, one should specify the localization of the pathologically altered synovium and determine whether the process is generalized, e.g. all metacarpophalangeal joints (MCP) or the sheaths of all extensor compartments are involved, or whether it is limited to single or several joints or sheaths. From the pathogenetic point of view, capsular synovitis, flexor or extensor tenosynovitis (tendovaginitis) or bursitis are manifested by synovial membrane thickening. Depending on the moment at which US examination is performed, the hyperemia of the synovium may not yet be visible, some single vessels may be observed and finally, the most typically for RA, intensive vascularization of the synovium may be present. The assessment of the degree of hyperemia is subjective, semiquantitative and is based on PDUS(6, 7). The literature presents several scales of semiquantitative assessment of synovial vascularization. For instance, the 0–3 score classification where 0 marks the lack of flow, 1 – visible one or two vessels in the area of the synovium, 2 – numerous vessels occupying approximately 50% of the thickened synovium, and 3 – numerous vessels that occupy more than 50% of the synovium. In another exemplary scale, score 0 means correct vascularization of the synovium (no or single vessels), 1 – low-degree hyperemia, 2 – moderate hyperemia, 3 – intense vascularization of the synovium. An example of the quantitative assessment, however, is the measurement of CF indicator (color fraction) which is a ratio of color pixels and all pixels in a marked area of interest. The analysis of the vascularization of the synovial membrane in PDUS is of clinical significance which is proven by the correlations between synovitis assessed in PDUS and the count of Th17 proinflammatory and destructive lymphocytes in the synovial fluid of patients with RA(8).

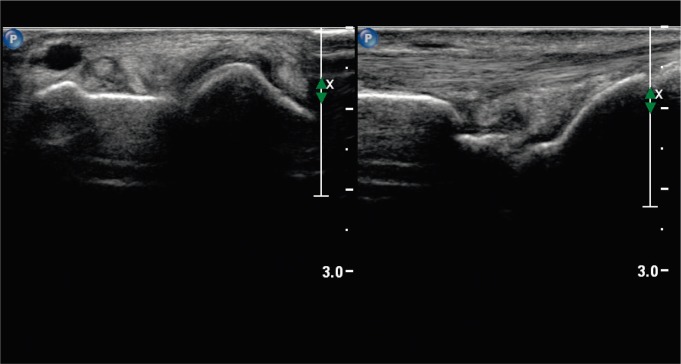

Fig. 2.

Thickening of the synovium in the DRUJ, radiocarpal and midcarpal joints (synovitis)

Fig. 3.

Thickening of the synovium of the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon sheat (tenosynovitis)

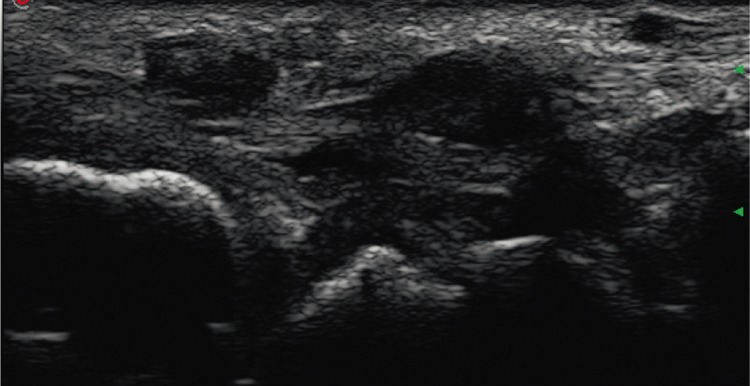

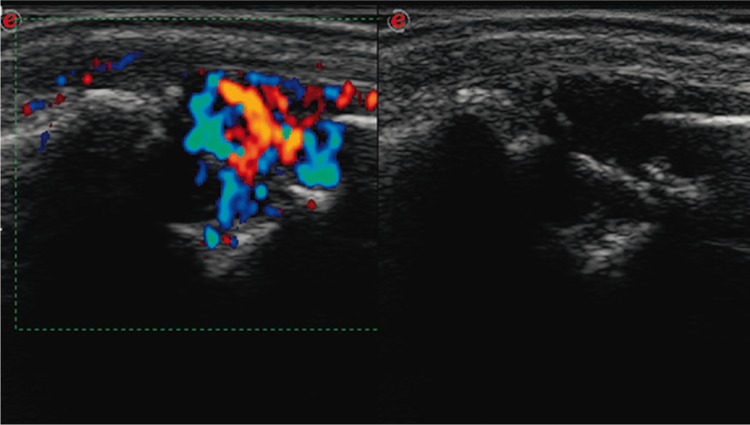

Fig. 4.

A. Thickening with vascularization of the synovium of the MCP joint (synovitis). B. Joint's pannus, which is an inflammatory granulation tissue composed of numerous tiny vessels and chronic inflammatory infiltrates. H&E staining, ×100

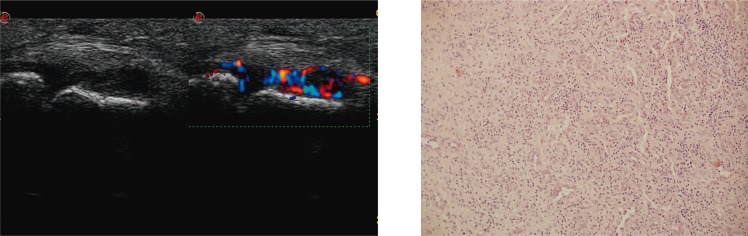

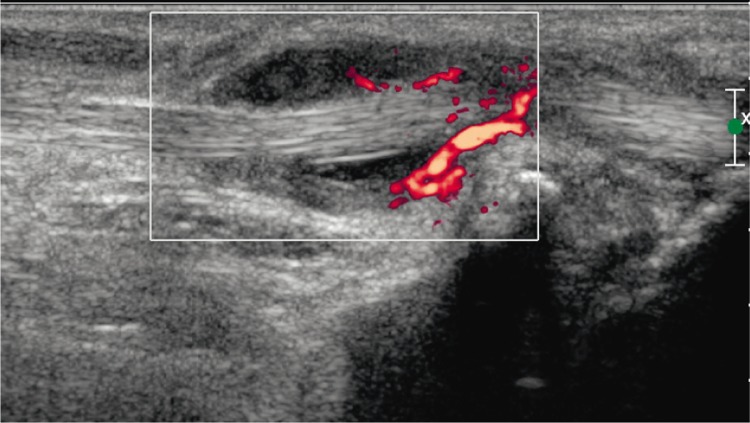

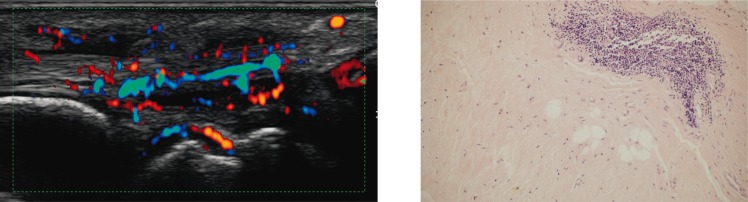

Fig. 5.

Thickening with vascularization of the synovium of the flexor carpi radialis tendon (tenosynovitis)

Active pannus (i.e. synovial membrane with active inflammation) leads to the damage of the articular structures. In the case of articular cavities, erosions are formed. Initially they are peripheral, i.e. occur in the region of the osseous junction of the articular capsule, and subsequently, subchondral, due to the damage of the articular cartilage(2). Geodes, however, attest to the presence of another diseased area in the subchondral osseous tissue(1). Geodes are visible on US image as defects in the subchondral layer covered with cortical layer. Erosions, on the other hand (analogically to a radiographic examination), are visible as an interruption in the outline of the cortical layer(1, 2, 6, 9). The synovium is frequently detected within the erosion and it may undergo fibrosis or be vascularized. The latter observation attests to the presence of an active process of articular structure deterioration (so called, active erosion) (fig. 6). The US access to the bone surfaces which compose the joints of the hand is limited. Therefore, sonography constitutes a supplementation of a radiographic examination, which, however, does not enable to visualize all the erosions either due to overlapping dorsal and ventral osseous masses(2). Thanks to multidimensional imaging, the leading method is MRI(2).

Fig. 6.

Active erosions in MCP joint with active pannus

The inflammatory process of the sheath, on the other hand, may also involve the tendon, which is defined as the inflammation of the tendon and tendon sheath(7) (fig. 7). The acute and active condition manifests itself with the hyperemia of the synovial sheath and hyperemia of the tendon. Chronic inflammatory condition and frequently accompanying mechanical factors connected with tendon movement over uneven bone surfaces, which are deteriorated by the inflammation, often leads to a partial or complete tendon rupture (fig. 8). In the case of a partial damage, hypoechoic tears are visible in the region of the thickened tendon. In the case of a complete rupture, however, a dynamic examination reveals splitting stumps. Prior to a planned surgery, it is essential to determine the distance between the stumps and their morphological condition.

Fig. 7.

A. Tendovaginitis and tendinitis of the extensor carpi ulnaris. B. Focal inflammatory infiltrate of the fibrous connective tissue of the tendon. H&E staining, ×100

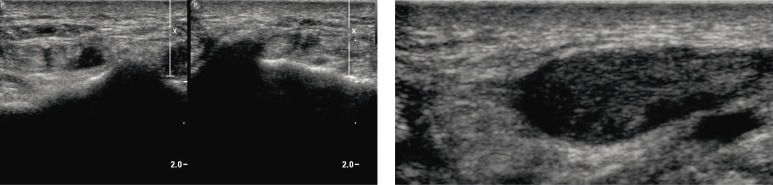

Fig. 8.

Complete tear of the extensor pollicis longus tendon: A. “empty” sheath at the level of the dorsal tubercle of the radius; B. distal stump of the torn tendon, which is thickened, degenerated, with intrasubstance tears

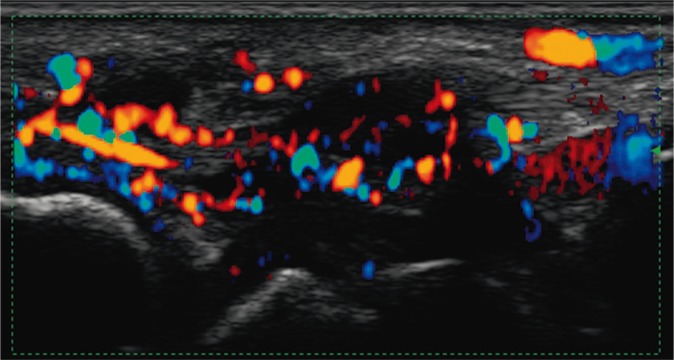

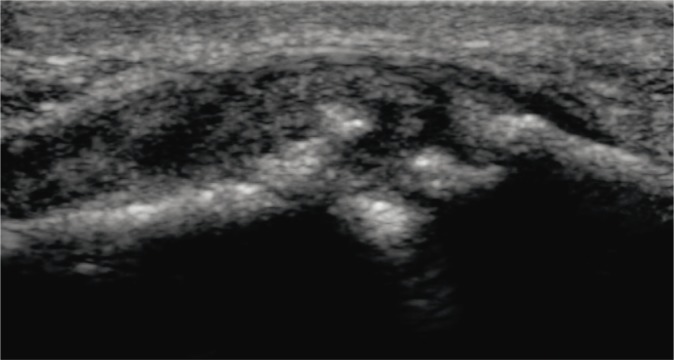

In the hand, the model of the cascade of inflammatory and destructive changes, which are brought about by the active pannus, is the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) (fig. 9). Here, the articular capsule and ligaments that stabilize the joint become damaged, erosions in the articular epiphyses occur and articular surfaces undergo damage. This results in the instability of the joint and dorsal dislocations or subluxations of the ulna. In the situation of the deterioration of the dorsal capsule-ligamentous complex of DRUJ, the bands of the extensor of finger 5 rub directly against a saw-like erosion site on the surface of the dorsal epiphysis of the distal ulna. Moreover, the pannus in the tendon sheath of the extensor carpi ulnaris may infiltrate into the tendon with its subsequent damage which is favored by the subluxation of the ulna bone and friction of the tendon against the deteriorated head of the ulna. The tendon retinaculum undergoes rupture as well(5).

Fig. 9.

Active tendovaginitis with tendinitis of the extensor carpi ulnaris

In US examination, one may observe anomalous joint position, which may be caused not only by damage to the articular surfaces in the late stages of the rheumatoid disease(10). Also in the early phase, a dynamic US examination may reveal the contracture of capsule-ligamentous structures of the interphalangeal joints (constraint in the natural hyperextension in the proximal interphalangeal joint – PIP). They are most frequently caused by a failure to begin rehabilitation at the onset of arthritis.

The pathologies presented above are not typical of RA only. Therefore, based on US examination, it is not possible to distinguish between individual rheumatoid entities, which would be desirable for instance, in the case of undifferentiated (unclassified) arthritis (UA). In this respect, the role of sonography is more difficult than X-ray scan in which the differentiation is based on the localization of the lesions and characteristic radiological features. There is probably only one instance when US differential diagnosis might be attempted, i.e. when a patient manifests inflammatory changes of the distal interphalangeal joint that coexist with entesopathy of the capsular and tendoligamentous attachments, including erosive and destructive changes with simultaneous proliferative lesions in the region of the epiphyses, which is pathognomonic for psoriatic arthritis (fig. 10). What is more, ultrasound symptoms characteristic of rheumatoid diseases (mainly synovitis, tenosynovitis and bursitis) may occur in the course of overuse, post-traumatic and degenerative changes(5, 11). Finally, the ultrasound image of the rheumatoid patients currently diagnosed in a very early stage (in a, so called, therapeutic window) is frequently different from the one familiar from course books, mainly from the radiological images. RA may constitute an example. In an early stage it might be localized in one or several sheaths “without” joint cavities. We are not familiar with radiological images (X-ray, US or MRI) of early phases of rheumatoid diseases and without proper clinical data we cannot differentiate between them yet. Pathogenetic knowledge and rheumatoid practice indicate that each instance of pain or edema of the joint should be explained within 6 weeks. Thanks to this, in the case of the diagnosis of inflammation, we might recommend a treatment in the period of, so called, therapeutic window, i.e. within 3 months from the onset of symptoms.

Fig. 10.

Erosive and proliferative inflammatory lesions in DIP3 joint of the hand

To sum up, sonography, a non-invasive and available examination, constitutes one of the supplementary examinations in the diagnosis of rheumatoid patients. It requires experience. It allows for the diagnosis of early inflammatory lesions in the soft tissues of the joints. Due to the fact that more and more patients report with an early stage of the disease, whose advancement, with a high probability, may be hindered by the implemented therapy, the significance of US examinations increase. Nonetheless, this modality has certain limitations. It renders the differentiation of individual rheumatoid diseases impossible. In many cases, it prevents the differentiation of rheumatoid diseases from degenerative, overuse or post-traumatic changes (such as overlap syndrome of RA and osteoarthritis or post-traumatic arthritis). Finally, it does not allow for the differentiation of the cause of persistent synovial membrane thickening or mean effusion in chronically ill patients (chronic inflammation or synovial membrane fibrosis?), which affects subsequent therapeutic decisions.

Conflict of interest

Authors do not report any financial or personal links with other persons or organizations, which might affect negatively the content of this publication and/or claim authorship rights to this publication.

References

- 1.Sudoł-Szopińska I, Kontny E, Maśliński W, Prochorec-Sobieszek M, Kwiatkowska B, Zaniewicz-Kaniewska K, et al. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis in radiological studies. Part I: Formation of inflammatory infiltrates within the synovial membrane. J Ultrason. 2012;12:202–213. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2012.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sudoł-Szopińska I, Zaniewicz-Kaniewska K, Warczyńska A, Matuszewska G, Saied F, Kunisz W. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis in radiological studies. Part II: Imaging studies in rheumatoid arthritis. J Ultrason. 2012;12:319–328. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2012.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sudoł-Szopińska I, Kontny E, Maśliński W, Prochorec-Sobieszek M, Warczyńska A, Kwiatkowska B. Significance of bone marrow edema in pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Pol J Radiol. 2013;78:57–63. doi: 10.12659/PJR.883768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sudoł-Szopińska I, Kontny E, Zaniewicz-Kaniewska K, Prohorec-Sobieszek M, Saied F, Maśliński W. Role of inflammatory factors and adipose tissue in pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Part I: Rheumatoid adipose tissue. J Ultrason. 2013;13:192–201. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2013.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinoli C, Bianchi S. Nadgarstek. In: Bianchi S, Martinoli C, editors. Ultrasonografia układu mięśniowo-szkieletowego. Vol. 1. Warszawa: MediPage; 2008. pp. 425–494. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boutry N, Morel M, Flipo RM, Demondion X, Cotten A. Early rheumatoid arthritis: a review of MRI and sonographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:1502–1509. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bliddal H, Boesen M, Christensen R, Kubassova O, Torp-Pedersen S. Imaging as a follow-up tool in clinical trials and clinical practice. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:1109–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gullick NJ, Evans HG, Church LD, Jayaraj DM, Filer A, Kirkham BW, et al. Linking power Doppler ultrasound to the presence of Th17 cells in the rheumatoid arthritis joint. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grainger AJ, McGonagle D. Imaging in rheumatology. Imaging. 2007;19:310–323. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wakefield RJ, O'Connor PJ, Conaghan PG, McGonagle D, Hensor EM, Gibbon WW, et al. Finger tendon disease in untreated early rheumatoid arthritis: a comparison of ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1158–1164. doi: 10.1002/art.23016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teh J. Ultrasound of soft tissue masses of the hand. J Ultrason. 2012;12:381–401. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2012.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]