Abstract

Ultrasonography is the most widespread imaging technique used in the diagnostics of the pathologies concerning the organs in the abdominal cavity. Similarly to other diagnostic tools, errors may occur in ultrasound examinations. They generally result from inappropriate techniques, which do not conform to current standards, or erroneous interpretation of obtained images. A significant portion of mistakes is caused by inappropriate quality of the apparatus, the presence of sonographic imaging artifacts, unfavorable anatomic variants or improper preparation of the patient for the examination. This article focuses on the examiner-related errors. They concern the evaluation of the liver size, echostructure and arterial and venous vascularization as well as inappropriate interpretation of the liver anatomic variants and the vascular and ductal structures localized inside of it. Furthermore, the article presents typical mistakes made during the diagnosis of the most common gallbladder and bile duct diseases. It also includes helpful data concerning differential diagnostics of the described pathologies of the liver, gallbladder and bile ducts. The article indicates the most frequent sources of mistakes as well as false negative and false positive examples which result from these errors. What is more, the norms used in the liver, gallbladder and bile duct evaluations are presented as well as some helpful guidelines referring to the exam techniques and image interpretation, which allows for reducing the error-making risk. The article has been prepared on the basis of the report published in 2005 by the Polish experts in the field of ultrasonography and extended with the latest findings obtained from the pertinent literature.

Keywords: diagnostic errors, ultrasound diagnostics, bile duct diseases, liver diseases, gallbladder diseases

Abstract

Ultrasonografia jest najbardziej rozpowszechnioną techniką obrazowania w diagnostyce chorób narządów jamy brzusznej. Podobnie jak w przypadku innych narzędzi diagnostycznych badanie ultrasonograficzne obarczone jest ryzykiem popełniania błędów. Na ogół wiążą się one z niewłaściwą techniką wykonywania badania, niezgodną z obowiązującymi standardami, bądź mylną interpretacją uzyskiwanego obrazu. Znaczna część popełnianych pomyłek wynika także z nieodpowiedniej jakości stosowanego sprzętu, z obecności artefaktów obrazowania ultrasonograficznego, niekorzystnych warunków anatomicznych lub z niewłaściwego przygotowania chorego do badania. W niniejszej pracy skoncentrowano się na błędach zależnych od badającego. Dotyczą one oceny wymiarów wątroby, jej echostruktury oraz unaczynienia tętniczego i żylnego, niewłaściwej interpretacji wariantów anatomicznych wątroby, położonych w niej struktur naczyniowych i przewodowych. Ponadto przedstawiono typowe pomyłki pojawiające się w trakcie prowadzenia diagnostyki najczęstszych chorób pęcherzyka żółciowego i dróg żółciowych. W pracy zawarto przydatne dane dotyczące diagnostyki różnicowej opisywanych patologii wątroby, pęcherzyka żółciowego i dróg żółciowych. Wskazano najczęstsze źródła popełnianych pomyłek i przykłady wynikających z nich wyników fałszywie dodatnich i ujemnych. Poza tym przedstawiono zakresy norm stosowanych w ocenie wątroby, pęcherzyka żółciowego i dróg żółciowych oraz zawarto przydatne wskazówki dotyczące techniki badania, interpretacji uzyskiwanego obrazu, pozwalające zminimalizować ryzyko popełnienia pomyłek. Artykuł został przygotowany na podstawie opracowania opublikowanego przez polskich ekspertów z dziedziny ultrasonografii w 2005 roku i pogłębiony o najnowsze doniesienia z piśmiennictwa.

Introduction

Ultrasound (US) examination constitutes the first choice test in the diagnostics of the liver gallbladder and bile ducts diseases. The technological advancement ensures constant modification of the US apparatus parameters, which enables to improve the image quality and extends the scope of possibilities of assessing the tested tissues. On the other hand, compared to other imaging methods, ultrasonography remains the most operator-dependent technique. Consequently, the possibilities to assess organs are better, but the risk of making diagnostic errors remains. The mistakes may be generally divided into those resulting from:

inadequate equipment quality;

improper cooperation with the patients during the examination;

inappropriate preparation of the patient for the test;

impossibility of obtaining an optimal image of the tested organs;

inappropriate interpretation of the structure and character of lesions.

The first four reasons may be independent of the examiner. The last one, however, may result from:

the lack of complete information obtained from the interview, physical examination and the results of the tests performed so far;

a mistake caused by inappropriate patient position and testing technique;

creation of false images and their interpretation;

too fast and superficial examination;

concentrating on a single identified pathology and inadequate assessment of other organs;

insufficient examiner's knowledge.

This article constitutes a review of the most common diagnostic errors in US examinations of the liver, gallbladder and bile ducts.

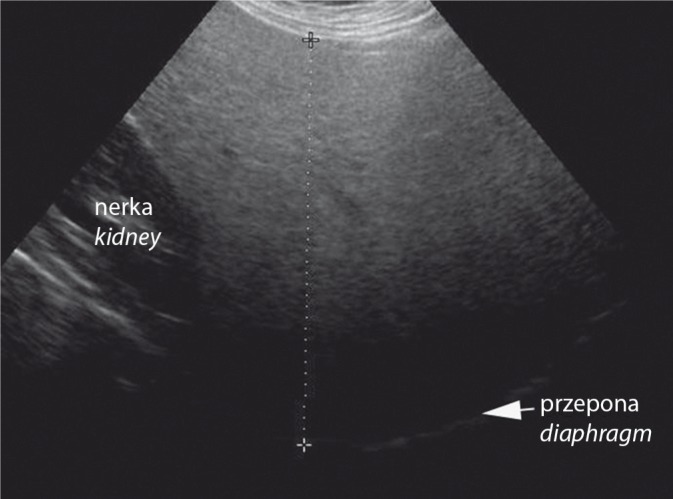

Errors in the liver evaluation

The assessment of the liver size

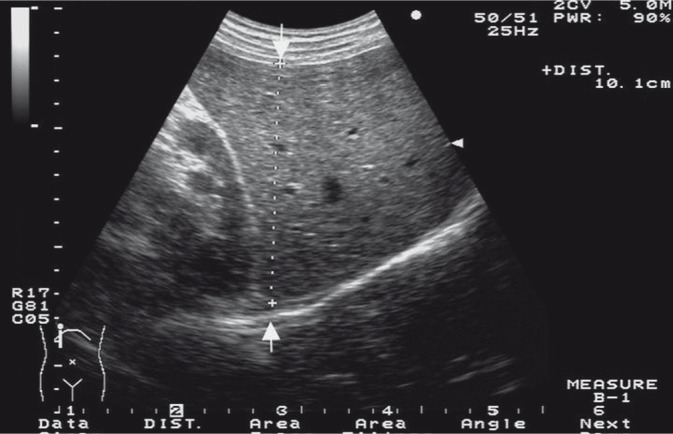

Usually the anteroposterior (a-p) part of the right lobe is measured. In order to obtain the proper value, the transducer needs to be placed in a sagittal position in the right midclavicular line at the moment of inhalation – when the diaphragm takes the lowest position (fig. 1)(1). In the majority of patients (about 90%), the anteroposterior size of the right liver lobe does not exceed 120 mm. When assessing the liver measurements, one should take into consideration the patient's height, age as well as stature (athletic vs. asthenic). If doubts occur concerning the diagnosis of hepatomegaly, which is a pathological condition and accompanies numerous diseases, one should conduct longitudinal measurements of the right lobe with the same application of the transducer (i.e. midclavicular line) as well as longitudinal measurements of the left lobe in the median line with longitudinal transducer application. Only on the basis of meticulous analysis of the obtained values, may conclusions be formulated concerning possible organomegaly (tab. 1).

Fig. 1.

The a-p measurement of the right liver lobe

Tab. 1.

Liver size according to Niederau(2)

| Size [mm] | SD | 95 percentile | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Midclavicular line | |||

| Longitudinal size | 105 mm | 15 mm | 126 mm |

| Anteroposterior size | 81 mm | 19 mm | 113 mm |

| Median line | |||

| Longitudinal size | 83 mm | 17 mm | 109 mm |

| Anteroposterior size | 57 mm | 15 mm | 82 mm |

According to Gosink, the anteroposterior size of the right lobe should not exceed 130 mm. The a-p size >150 mm indicates a pathology in 75% of cases. According to this author, the a-p size values of the right liver lobe between 130 and 150 mm do not require individual assessment(3).

Some patients, particularly women with asthenic stature, present an anatomical variant of the right liver lobe, i.e. the extension of the lobe's lower edge called the Riedel's lobe (fig. 2). Such a presentation is erroneously assessed as hepatomegaly.

Fig. 2.

Riedel's lobe

Additional fissures in the liver

The presence of additional fissures in the liver may be mistakenly interpreted as a normo- or hypoechogenic focal lesion as well as an encapsulated lesion of the right liver lobe, while it is a separate fragment of normal liver parenchyma. An erroneous assessment of the adipose tissue contained in the round ligament of the liver as a focal steatosis or hemangioma constitutes another frequent error (fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The round ligament of the liver

Caudate lobe

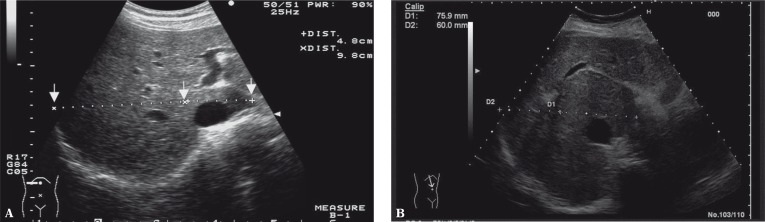

In the course of cirrhosis and in Budd-Chiari syndrome, the caudate lobe becomes enlarged(4). When assessing the size of the caudate lobe, the so-called Harbin's index is used, i.e. a ratio of the transverse size of the caudate lobe to the transverse size of the right lobe. The quotient >0.55 indicates cirrhosis with the specificity of 100% and sensitivity of 72% (fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The ratio of the transverse size of the caudate lobe to the transverse size of the right liver lobe

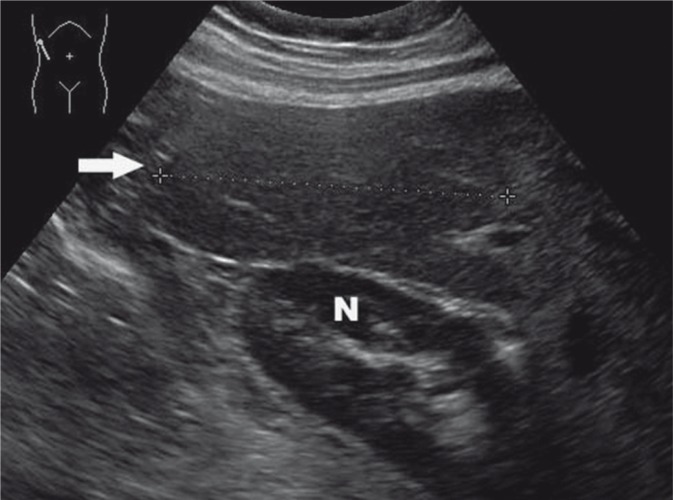

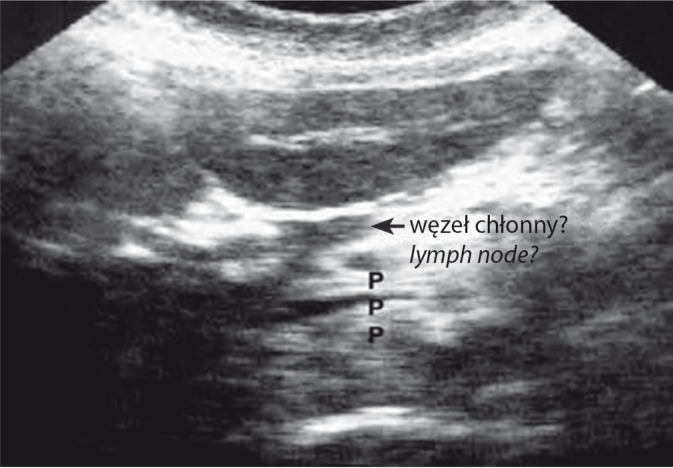

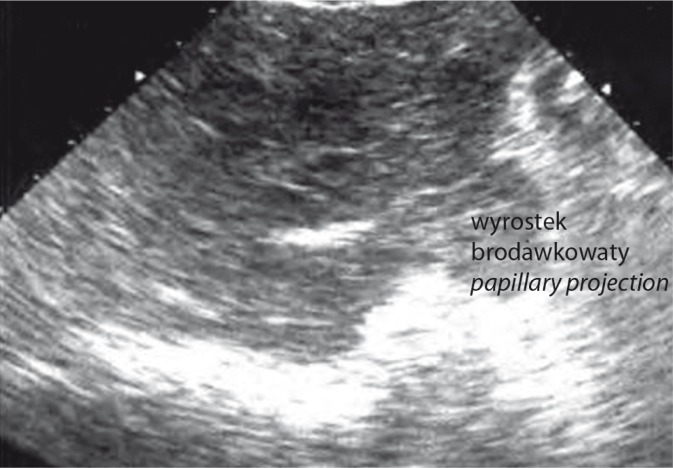

In the caudate lobe, there is an interesting anatomical variant which is often mistaken for enlarged lymph nodes or pancreatic tumors. These are single or multiple finger-like projections, also called the papillary projections (figs. 5, 6).

Fig. 5.

A finger-like projection of the caudate lobe interpreted as an enlarged lymph node

Fig. 6.

A papillary projection of the caudate lobe interpreted as a pancreatic tumor

Hepatic veins

An error connected with the interpretation of hepatic vein dilatation is made quite frequently. Pathologically dilated hepatic veins, which give symptoms of socalled antlers of a deer, are observed in patients with right ventricular heart failure. Irrespective of hepatic vein dilatation, these patients also present hepatomegaly, which depends on the duration of heart failure. In acute circulatory insufficiency, manifested as hemostasis, the liver echogenicity is decreased as a result of parenchymal edema. Whereas in chronic decompensated heart failure, the echogenicity may be heterogeneously increased due to parenchymal structural alterations. Moreover, in slim, cachectic and elderly patients, the majority of venous vessels of the abdomen are wider, which is not related to any pathology. If doubts occur, the Valsalva maneuver is a valuable technique to resolve them. When performing it with the patient breathing easily, no significant differences are observed in the dimensions of hepatic veins and inferior vena cava (IVC) in the case of circulatory insufficiency – as compared with the condition of increased pressure in the abdomen. The presence of the gallbladder in the fossa of the IVC also constitutes a cause of errors.

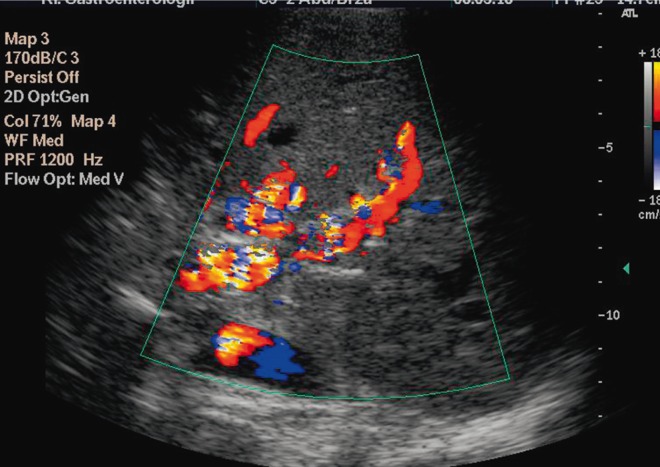

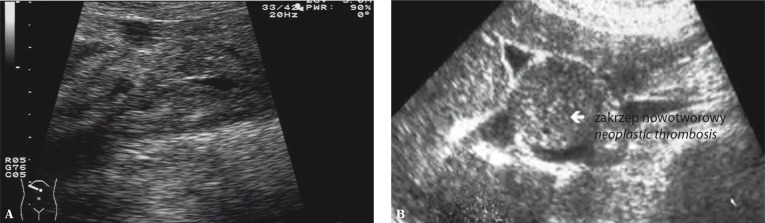

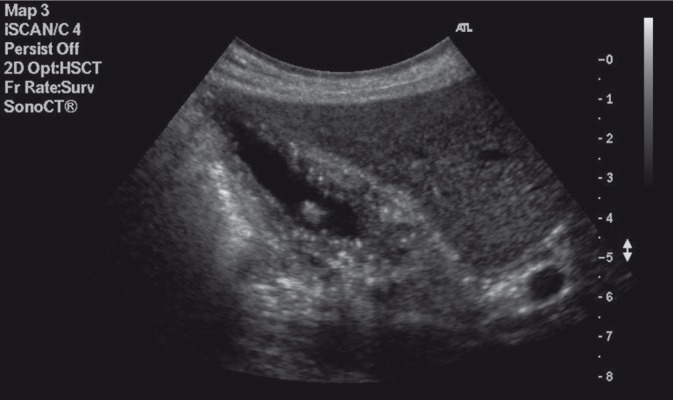

Portal vein

The portal vein trunk is usually well visible in US examinations. The most commonly made error is the failure to visualize the thrombus in the portal vein. So as to avoid this mistake, one should carefully study and evaluate the portal vein walls which, if a thrombus is present, are uncircumscribed in the first stage of the test. Around the vein, hypoechogenic and irregular image of the inflammatory infiltration is frequently observed. The clot itself is not visible in the first stages of the disease due to its low, fluidlike echogenicity. The consequence of the portal vein thrombosis is the portal hypertension, the diagnosis of which may be aided by Doppler and color Doppler techniques(5). When the portal vein does not undergo recanalization, in a US examination performed after a dozen, or so, months after the thrombosis, one can find the portal vein cavernous transformation in the liver hilum (fig. 7). It presents slight hypoechogenic areas which correspond to the vessels of collateral circulation and which are repeatedly mistaken for enlarged lymph nodes in the liver hilum(1). Color Doppler resolves such doubts. False positive thrombosis recognition is also possible particularly in persons with cirrhosis whose speed of the blood flow in the portal vein may be so low that no Doppler signal is detected. Another pathological US presentation in the case of the portal vein and its branches is the presence of neoplastic thrombi. Such masses, however, never cause the complete obstruction of the vein or its branches and are clearly visible in the vessel lumen as areas of various shapes and echogenicity (fig. 8 A, B). Hence, the phenomenon of the cavernous transformation is not observed(1).

Fig. 7.

The cavernous transformation of the portal vein

Fig. 8.

A. Neoplastic invasion of the portal vein. B. A mass in the portal vein imitates the liver tumor

Hepatic artery

In the majority of cases, the common hepatic artery arises from the celiac artery. Nonetheless, various anatomical variants exist. The most common variations constitute the origin of the common arterial trunk or the right hepatic artery, or the posterior branch of the right hepatic artery, in the superior mesenteric artery. Such a situation is a cause of numerous errors in the identification of the common bile duct and the misinterpretation of the artery for a bile duct(1).

The assessment of the hepatic parenchyma

Against all appearances, the assessment of the hepatic parenchyma is not easy. It is assumed that the echogenicity of the healthy liver should be slightly higher than that of the renal cortex and slightly lower than that of the spleen(5). Moreover, normal parenchyma presents a clearly visible branching of the portal system and posterior part of the right liver lobe. In the cases of increased echogenicity of the parenchyma which is observed in liver steatosis, the visibility of the portal system and the posterior part of the right liver lobe decreases as the disease progresses. Hepatic parenchymal steatosis appears in numerous pathologies which need to be included in the differential diagnostics (fig. 9)(6). In a significant number of cases, steatosis does not affect the whole parenchyma equally. In such a situation, the areas of so-called focal hyposteatosis are visible in the region of the gallbladder and in the medial part of the left liver lobe above the portal vein. They present themselves as irregular areas of various shapes, which are hypoechogenic and whose localization and presentation do not raise any doubts concerning their benign nature(7). It happens, however, that hyposteatosis areas are localized atypically. In such situations, in order to avoid errors, one needs to differentiate them from other benign or malignant hepatic focal lesions which appear in the parenchyma. Another form of parenchymal structure alteration is focal steatosis of the hepatic parenchyma (fig. 10). Here, the focal lesions must be differentiated from other hyperechogenic areas in the vicinity of the liver. If the areas are multiform, without infiltration and compression on vascular structures and bile ducts, they correspond to steatosis. If they are round, they, above all, require the differentiation from hemangiomas. Further comes the differentiation from hyperechogenic malignant lesions, both primary and metastatic(8).

Fig. 9.

Steatosis of the liver parenchyma

Fig. 10.

Focal steatosis of the liver parenchyma

In advanced cirrhosis, the assessment of the liver is not problematic. In order to avoid mistakes in US image, the evaluation of the liver outlines should be performed by means of high-frequency transducers (7–10 MHz) which enable to assess the regularity of the margins and the liver size(9). The observation is made easier by the presence of free fluid in the peritoneal cavity. The greatest difficulty in the evaluation of cirrhotic liver is posed by the presence of regenerative nodules which are usually normoechogenic and thus, impossible to differentiate on the basis of US examination from the normoechogenic form of multinodular hepatocellular carcinoma or with metastatic changes (fig. 11). Such an image constitutes an indication for tests using intravenous contrast agents (CT, MRI, CEUS). The evaluation of collateral circulation in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension poses another problem. The vessels of the collateral circulation, which are formed in the vicinity of the spleen and liver helium, are mistaken for enlarged lymph nodes of this region. For differentiation, Doppler ultrasound should be performed.

Fig. 11.

A regenerative nodule in the cirrhotic liver

In acute inflammations of the hepatic parenchyma, the US image often presents centrilobular structure alterations(9). The liver is slightly enlarged with decreased echogenicity, but the hepatic triads are distinctly more enhanced with even their slight branches clearly visible. Moreover, the thickening of the gallbladder wall and splenomegaly are visible. Such a presentation may also appear in granulomatous, bacterial and parasitic diseases, which need to be included in the differential diagnostics. It must be remembered, however, that a similar image may appear in healthy persons, particularly young and slim. Nonetheless, there are no deviations in the images of the gallbladder and spleen.

Gallbladder

Gallbladder size

The parameter included in the size assessment of the gallbladder is its width which in normal persons constitutes between 20 and 40 mm. Due to various shapes of this organ, the longitudinal size is less often measured. Enlarged gallbladder (>50 mm wide) is diagnosed in patients with acute cholecystitis as a result of the bile outflow obstruction by a stone blocked in the cystic duct. This complication, which is manifested by enhanced US image, is called cholecystocele in surgical terminology. A different image of the gallbladder is visible in the course of cholestasis which encompasses the intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts. The gallbladder is enlarged, contains concentrated bile and, sometimes, concretions. However, its wall remains thin and there is no so-called Murphy's sign (the elicitation of pain when the transducer is pressed against the gallbladder as viewed in the ultrasound image). Such a presentation is too often misinterpreted by ultrasonographers as a cholecystocele (although, contrary to cholecystocele discussed above, it does not require surgical intervention). The problem that is needed to be solved here is cholestasis. The enlarged gallbladder which is painless but well-palpable constitutes a Courvoisier's sign. It is observed in mechanical obstruction, which caused the bile stasis, localized in the head of the pancreas or in the common bile duct. The enlarged gallbladder with thin walls and without any signs of concretions or impaired patency of the bile ducts may appear in the case of diabetic neuropathies.

Cholelithiasis

The detection of cholelithiasis during US examination reaches 100% of cases. The error which appears most frequently in the diagnosis of this pathology is conducting the test on patients who are not fasted. In these cases, the gallbladder is contracted, has thick walls and its content is impossible to assess(10). Other problems concern the diagnosis of slight, non-calcified concretions (fig. 12) and concretions localized in the gallbladder neck or those coexisting with the gallbladder cancer. The most common false positive results refer to the erroneous interpretation of the presence of gases in the duodenum as concretions or calcified polyps. In order to avoid such a mistake, the gallbladder lumen must be assessed in several projections, which allow for the recognition of the gas particles imitating the gallbladder concretions. In case of doubts, the test should be repeated with the patient fasted.

Fig. 12.

A slight concretion in the gallbladder lumen

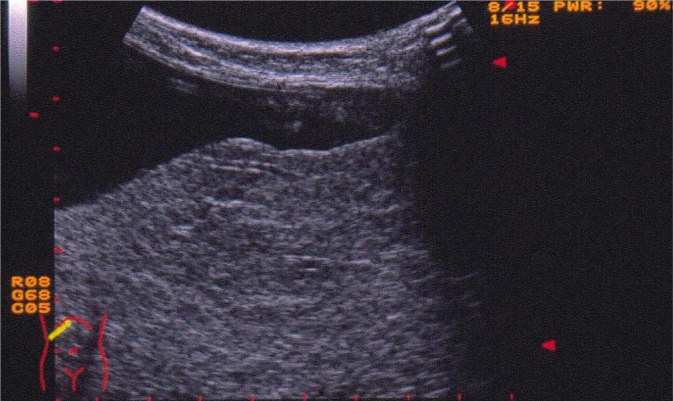

Acute cholecystitis

Acute cholecystitis is connected with unfavorable testing conditions for an ultrasonographer, i.e. pain, tension of abdominal integuments and flatulence. This can lead to errors in detection and localization of concretions while assessing the wall structure alteration and the degree of the inflammatory process especially in the case of torsion of the gallbladder and stoneless cholecystitis(11). A different type of mistakes is related to overinterpretation of the image and basing the diagnosis solely on the assessment of the gallbladder wall thickness. Gallbladder wall thickening is observed in numerous other diseases such as chronic cholecystitis, liver cirrhosis, conditions manifested as hypoproteinemia or ascites as well as hyperplastic cholecystoses and gallbladder cancer. Therefore, the appropriate diagnosis of acute cholecystitis, beside a typical clinical picture, should be based on additional examinations including a US test. The features of acute cholecystitis in US imaging are: cholelithiasis (90–95% of cases), positive US Murphy's sign (90–92%), wall thickening (50–75%), gallbladder shape and size alterations (30–45%), pericholecystic inflammation (10–20% of cases)(1). The greatest diagnostic problems are connected with the recognition of specific forms of acute cholecystitis such as: gangrenous, stoneless and emphysematous (caused by anaerobic bacteria) cholecystitis. In gangrenous cholecystitis, fast denervation of the gallbladder walls is observed and the positive US Murphy's sign disappears. The US image shows a typical irregular wall thickening and striation, pseudomasses in the lumen as well as pericholecystic inflammation (fig. 13). Despite this, the pathology may be undiagnosed and in a considerable number of cases, it results in severe complications, including the gallbladder perforation. In the case of the gallbladder perforation to the liver parenchyma, the US image shows the signs of hepatic abscess or pericholecystic inflammation. The US presentation may resemble that of gallbladder cancer. In acute cholecystitis caused by anaerobic bacteria, one should search for gas bubbles in the gallbladder lumen, wall, in the area of the pericholecystic inflammation and in the bile ducts.

Fig. 13.

Gangrenous cholecystitis

Gallbladder polyps

Sometimes, in the gallbladder lumen, there are polypous formations of various sizes and shapes, often with the structure of cholesterol pseudopolyps (50–60% of cases), and more rarely the inflammatory ones (5–10% of cases) (fig. 14). Polyps with neoplastic potential appear seldom (<5% of cases); they usually look like structures on a wide base and show growth. For the safety of the patients with polyps, periodical US check-ups should be conducted. If the gallbladder lesions grow fast or exceed the limit of 10 mm, its excision is recommended(12, 13). Apart from the differentiation of polyps, another interpretational problems may arise in connection with adenomyomatosis. This pathology consists in the proliferation of the muscle layer of the gallbladder wall into the region of the mucous membrane as well as formation of slight cysts and Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses in the gallbladder wall, in which cholesterol crystals may accumulate. As a result of so-called reverberation effect (alternating reflection of ultrasound waves by strongly-reflecting surfaces placed parallelly or nearly parallelly to each other), a US image appears which is mistaken for gas in the gallbladder wall.

Fig. 14.

Gallbladder polyps

Porcelain gallbladder

The porcelain gallbladder is visible during US test in the form of a single arch of calcified wall from which the acoustic shadow arises (fig. 15). Errors in the diagnosis of this pathology occur while conducting the differential diagnostics between cholelithiasis and a very rare form of acute cholecystitis, i.e. emphysematous cholecystitis (1% of cases)(14). It is worth noting that in porcelain gallbladder, the triad wall-echoshadow (WES) does not appear and that patients with emphysematous cholecystitis present turbulent clinical symptoms. Due to the risk of gallbladder cancer, which according to various researchers constitutes 0–7%, cholecystectomy is recommended as further treatment.

Fig. 15.

Porcelain gallbladder

Gallbladder cancer

The differences in the diagnosis of gallbladder cancer are highly dependent on its localization. There are three macroscopic types of this neoplasm:

The tumor in the region of the anatomical location of the gallbladder. The difficulties are connected with the identification of infiltrated gallbladder walls which frequently are invisible, determination of its shape as well as the differentiation from the hepatic flexure tumor in the large intestine. The condition is often misdiagnosed as gangrenous cholecystitis with pericholecystic inflammation.

Polypous form requiring the differentiation from benign gallbladder polyps.

Segmental or extensive gallbladder wall thickening (fig. 16). This form requires the differential diagnosis from the pathologies listed in tab. 2 (5).

Fig. 16.

Gallbladder cancer

Tab. 2.

Causes of gallbladder wall thickening

1. General diseases manifested as tissue edema:

|

2. Inflammatory diseases:

|

3. Neoplastic diseases:

|

4. Other:

|

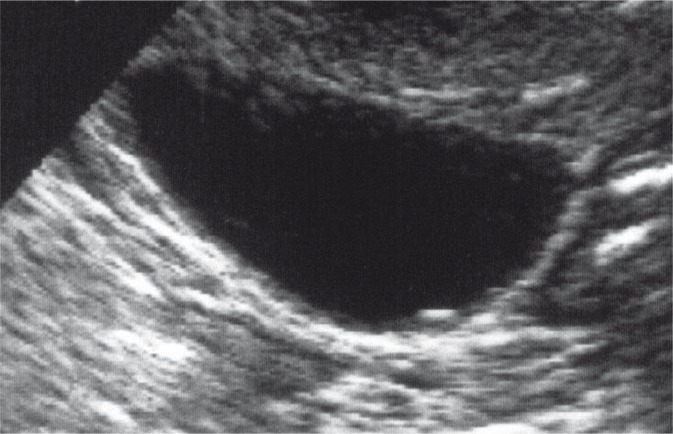

In the course of neoplasms, the wall thickening is usually slight and the echogenicity of walls is increased. The wall edema in non-neoplastic diseases with hypoalbuminemia causes significant gallbladder wall thickening. The echogenicity of the walls is low and their layered structure is often pronounced (fig. 17)(15, 16).

Fig. 17.

Gallbladder wall thickening which accompanies hypoalbuminemia

Bile ducts

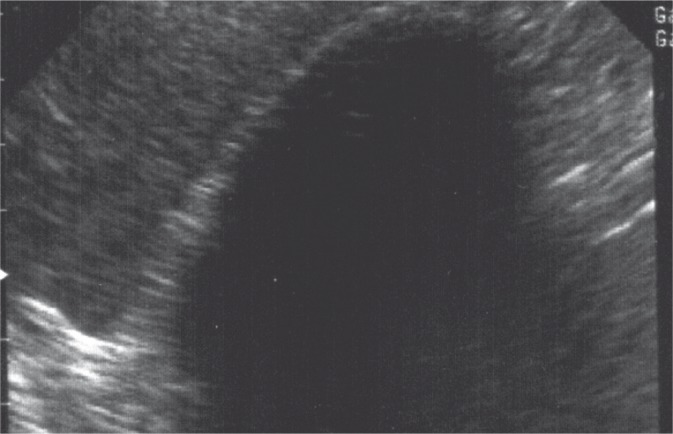

Intrahepatic bile ducts

In physiological conditions, the lumen diameter of the bile ducts is not greater than 2 mm. Thus, they may be invisible during the test. If dilated, their shape is irregular with the enhancement behind the posterior wall, which presents itself as so-called sea waves or, in the case of dilatation which is concentric in relation to the obstruction, the bile ducts form a spoke-wheel pattern (fig. 18). Errors in diagnosing dilated intrahepatic bile ducts may occur in patients with cirrhosis who present the dilated branches of the hepatic artery proper that imitate the dilated bile ducts. It is worth noting that arteries do not have an irregular course and their walls are smooth. Possible doubts may be finally resolved by a Doppler examination.

Fig. 18.

The dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts

In Mirizzi's syndrome, the clinical symptoms are caused by a compression of the stone and an inflamed region of the gallbladder neck on the junction of both hepatic ducts running in the vicinity. This causes the dilatation of intrahepatic bile ducts. Such a presentation is sometimes mistaken for choledocholithiasis, in particular in patients with acute cholecystitis. Accurate recognition of the Mirizzi's syndrome enables to avoid making the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis(17). The diagnostic problems also occur in the differentiation between the presence of concretions in the intrahepatic bile ducts and aerocholia in the patients who have undergone papillotomy, choledochoduodenostomy or hepaticoenterostomy and in the case of idiopathic cholecystoduodenal or cholecystoenteral fistula as well as in patients with acute emphysematous cholecystitis. Both concretions and air give acoustic shadow. Additionally, the air frequently causes a so-called dirty shadow, i.e. an incomplete shadow in the form of intense bands constituting a “comet tail”(1).

Common bile duct (CBD)

The visualization of the entire CBD helps to avoid the error of not noticing concretions or other pathological changes. The duct may be localized from the site of the hepatic hilum above the portal vein trunk or from the head of the pancreas. A normal width of the CBD does not exceed 6 mm(14). This value, however, varies and depends on age. It increases by 1 mm every 10 years after the age of 50 as well as in some persons after cholecystectomy – here the correct width limit is even 10 mm. The most common error made in the diagnosis of the CBD diseases is the failure to detect the concretions. The end fragment of the CBD, where concretions accumulate frequently, is especially susceptible to errors. What makes the evaluation of this region difficult is the presence of gas and fluid in the duodenum as well as thickening and diverticula caused by the concretions. Another place where concretions are often missed is the area of the junction of the hepatic ducts into the common hepatic duct. Last but not least, concretions are often undiagnosed in an undilated common bile duct when its visibility and evaluation is insufficient(1). The pathologies which imitate the CBD concretions appear rarely. Apart from concretions and neoplastic lesions in the CBD lumen, one may detect a non-calcified echo which needs to be differentiated from biliary sludge, benign and malignant tumors of the bile duct, gas particles or presence of blood clots. The interpretational problems may relate to persons with the history of cholecystectomy with surgical clips in the area of the liver hilum. In these cases the dilatation of the bile ducts is rare. Klatskin tumor also poses diagnostic difficulties. It is a neoplasm affecting the areas of the hepatic duct junction and the starting part of the CBD. The ultrasound image shows intrahepatic cholestasis and the lesion itself is not usually visible. An image of the undilated CBD below the obstruction constitutes a characteristic feature(1). Furthermore, the diagnostic problems are posed by cholangitis often occurring in patients with choledocholithiasis or hepaticoenterostomies. In certain cases the dilatation of the CBD walls is observed as well as the presence of concretions or gas bubbles. Unfortunately, the image is untypical and unambiguous US evaluation is difficult. It must be emphasized that the differentiation between similar CBD lesions in the US image should be performed bearing in mind a detailed doctorpatient interview and physical examination.

Conclusion

This article discussed the most common diagnostic errors and mistakes in US examinations of the liver, gallbladder and bile ducts. In order to avoid them, one must comply with the key principles such as: taking history, performing physical examination before the test, conducting a thorough US test according to current standards, making the most accurate diagnosis including the differential diagnostics and provision of further diagnostic algorithm in the case of doubts concerning the interpretation of the obtained US image of the examined organs.

Conflict of interest

Authors do not report any financial or personal links with other persons or organizations, which might affect negatively the content of this publication and/or claim authorship rights to this publication.

References

- 1.Jakubowski W, editor. Praktyczna Ultrasonografia. Warszawa – Zamość: Roztoczańska Szkoła Ultrasonografii; 2005. Błędy i pomyłki w diagnostyce ultrasonograficznej; pp. 69–112. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niederau C, Sonnenberg A, Müller JE, Erckenbrecht JF, Scholten T, Fritsch WP. Sonographic measurements of the normal liver, spleen, pancreas, and portal vein. Radiology. 1983;149:537–540. doi: 10.1148/radiology.149.2.6622701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gosink BB, Leymaster CE. Ultrasonic determination of hepatomegaly. J Clin Ultrasound. 1981;9:37–44. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870090110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giorgio A, Amoroso P, Lettieri G, Fico P, de Stefano G, Finelli L, et al. Cirrhosis: value of caudate to right lobe ratio in diagnosis with US. Radiology. 1986;161:443–445. doi: 10.1148/radiology.161.2.3532188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rumack CM, Wilson SR, Charboneau JW, Levine D, editors. Diagnostic Ultrasound. 4. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Mosby Inc; 2011. pp. 78–145. 172–215. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernaez R, Lazo M, Bonekamp S, Kamel I, Brancati FL, Guallar E, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and reliability of ultrasonography for the detection of fatty liver: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2011;54:1082–1090. doi: 10.1002/hep.24452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aubin B, Denys A, Lafortune M, Déry R, Breton G. Focal sparing of liver parenchyma in steatosis: role of the gallbladder and its vessels. J Ultrasound Med. 1995;14:77–80. doi: 10.7863/jum.1995.14.2.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tchelepi H, Ralls PW, Radin R, Grant E. Sonography of diffuse liver disease. J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:1023–1032. doi: 10.7863/jum.2002.21.9.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jakubowski W, editor. Praktyczna Ultrasonografia. 4. Warszawa – Zamość: Roztoczańska Szkoła Ultrasonografii; 2011. Standardy badań ultrasonograficznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Ultrasonograficznego; pp. 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanders G, Kingsnorth AN. Gallstones. BMJ. 2007;335:295–299. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39267.452257.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiewiet J, Leeuwenburgh MM, Bipat S, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J, Boermeester MA. A systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic performance of imaging in acute cholecystitis. Radiology. 2012;264:708–720. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mainprize KS, Gould SW, Gilbert JM. Surgical management of polypoid lesions of the gallbladder. Br J Surg. 2000;87:414–417. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kratzer W, Haenle MM, Voegtle A, Mason RA, Akinli AS, Hirschbuehl K, et al. Ultrasonographically detected gallbladder polyps: a reason for concern? A seven-year follow-up study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:41–49. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubens DJ. Ultrasound imaging of the biliary tract. Ultrasound Clin. 2007;2:391–413. [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Breda Vriesman AC, Engelbrecht MR, Smithuis RH, Puylaert JB. Diffuse gallbladder wall thickening: differential diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:495–501. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gore RM, Yaghmai V, Newmark GM, Berlin JW, Miller FH. Imaging benign and malignant disease of the gallbladder. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002;40:1307–1323. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(02)00042-8. vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abou-Saif A, Al-Kawas FH. Complications of gallstone disease: Mirizzi syndrome, cholecystocholedochal fistula, and gallstone ileus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:249–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]