Abstract

Similarly to entrapment neuropathies of upper extremities, the ultrasound constitutes a valuable supplementation of diagnostic examinations performed in patients with suspicions of nerve entrapment syndromes of the lower limb. For many years, it was claimed that such pathologies were rare. This probably resulted from the lack of proper diagnostic tools (including high frequency ultrasound transducers) as well as the lack of sufficient knowledge in this area. In relation to the above, the symptoms of compression neuropathies were frequently interpreted as a manifestation of pathologies of the lumbar part of the spine or a other orthopedic disease (degenerative or overuse one). Consequently, many patients were treated ineffectively for many months and even, years which led to irreparable neurological changes and changes in the motor organ. Apart from a clinical examination, the diagnostics of entrapment neuropathies of lower limb is currently based on imaging tests (ultrasound, magnetic resonance) as well as functional assessments (electromyography). Magnetic resonance imaging is characterized by a relatively low resolution (as compared to ultrasound) which results in limited possibilities of morphological evaluation of the visualized pathology. Electromyography allows for the assessment of nerve function, but does not precisely determine the type and degree of change. This article presents examples of the most common entrapment neuropathies of the lower limb concerning the following nerves: sciatic, femoral, lateral femoral cutaneous, obturator, fibular and its branches, tibial and its branches as well as sural. The pathomorphological basis of the neuropathies as well as corresponding ultrasound images are presented in this paper. Attention has been drawn to echogenicity, degree of vascularization and bundle presentation of the trunk of a pathological peripheral nerve.

Keywords: lower extremity neuropathies, ultrasound, peripheral nerves, nerve compression syndromes, entrapment syndromes

Abstract

Podobnie jak w przypadku neuropatii uciskowych kończyny górnej badanie ultrasonograficzne jest cennym uzupełnieniem badań diagnostycznych przeprowadzanych u pacjentów z podejrzeniem zespołów uciskowych nerwów kończyny dolnej. Przez wiele lat uważano, że tego rodzaju patologie występują rzadko. Prawdopodobnie było to efektem braku odpowiednich narzędzi diagnostycznych (w tym głowic ultradźwiękowych o wysokich częstotliwościach), jak również braku dostatecznej wiedzy na ten temat. Wobec powyższego objawy neuropatii uciskowych często interpretowano jako wyraz patologii odcinka lędźwiowego kręgosłupa lub innej choroby ortopedycznej (o podłożu zwyrodnieniowym czy przeciążeniowym). W rezultacie niejednokrotnie pacjenci byli nieskutecznie leczeni przez wiele miesięcy, a nawet lat, co prowadziło do nieodwracalnych zmian neurologicznych oraz zmian w narządzie ruchu. Diagnostyka neuropatii uciskowych kończyny dolnej opiera się obecnie, poza badaniem klinicznym, na badaniach obrazowych (badanie ultrasonograficzne i rezonans magnetyczny) oraz czynnościowych (elektromiografia). Rezonans magnetyczny cechuje relatywnie niska (w porównaniu z ultrasonografią) rozdzielczość, co skutkuje ograniczonymi możliwościami oceny morfologicznej uwidocznionej patologii. Elektromiografia pozwala na ocenę funkcji nerwu, jednak bez dokładnego określenia typu i poziomu zmian. W pracy omówiono przykłady najczęstszych neuropatii uciskowych kończyny dolnej, dotyczących nerwu kulszowego, udowego, skórnego bocznego uda, zasłonowego, nerwu strzałkowego i jego gałęzi, nerwu piszczelowego i jego gałęzi oraz nerwu łydkowego. Przedstawiono podłoże patomorfologiczne neuropatii oraz odpowiadające im obrazy ultrasonograficzne. Zwrócono uwagę na echogeniczność, stopień unaczynienia oraz rysunek pęczkowy objętego patologią pnia nerwu obwodowego.

Introduction

The most common compression neuropathies comprise: piriformis syndrome, femoral nerve neuropathy, Roth syndrome, neuropathies of the trunk and branches of the fibular nerve, neuropathies of the trunk and branches of the tibial nerve as well as sural nerve neuropathy. The ultrasound (US) image of the changes in peripheral nerve entrapment syndromes is identical to that of the upper extremities and was described in detail in Part I of the paper(1). It includes the enlargement of the diameter and cross sectional area of the nerve trunk, hourglass narrowing on the longitudinal section, bundle echostructure disorder and hyperemia above the site of compression. Below, a description of compression neuropathies of lower extremities is presented with particular attention drawn to pathomechanisms and corresponding US images.

Sciatic nerve

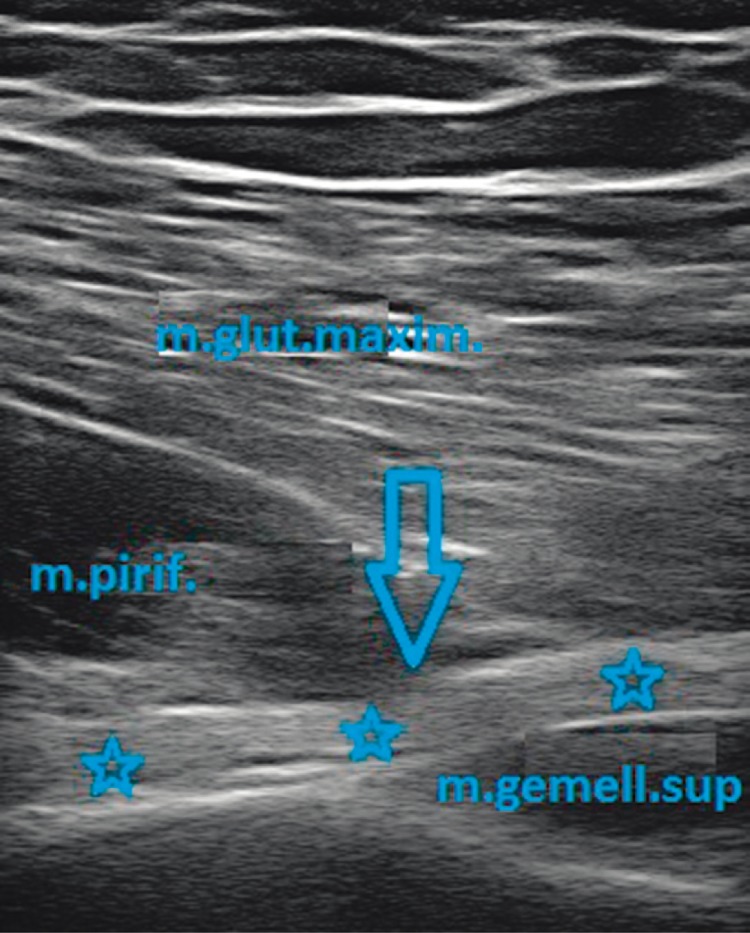

Compression neuropathy of the sciatic nerve is caused by nerve trunk entrapment in the region of the greater sciatic foramen and piriformis (fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Arrow indicates the site where the sciatic nerve (asterisks) emerges from under the piriformis muscle – m.pirif. (m.gemell.sup – gemellus superior muscle, m.glut.maxim. – gluteus maximus muscle)

The sciatic nerve may present anatomical distinctness in the area of the exit from the pelvis where, instead of going under, it runs through the piriformis. This variant concerns ca. 25% of people(2). The nerve may also undergo a high division into the fibular and tibial parts, one of which emerges from the pelvis running under this muscle, the other running through its belly. Inborn anatomical anomalies may also encompass superior and inferior gluteal vessels (as additional vascular loops or other malformations which entrap the nerve). The anomalies listed may constitute a predisposition to the development of neuropathic lesions(3).

During the US examination, one should measure the area of the nerve and compare it with the fragment situated below the site of compression as well as with the contralateral site on analogical height. In young and slim patients, the assessment of the nerve in the buttock should not pose any problems. Sometimes, however, it is more difficult it elderly (due to atrophic, regressive changes in the gluteal muscles) and in obese patients. In such a situation, a convex transducer should be used so as to increase the depth of the ultrasound penetration.

A permanent examination element is the comparison of the volume (thickness) and echostructure of the piriformis, which may undergo an idiopathic hyperplasia, with the contralateral side. Rarely, the volume growth of the piriformis results from inflammation or proliferative changes. It is recommended to assess its echogenicity in order to check for any posttraumatic or postinfection scars(2, 4). The assessment of this region requires particular care in patients after total hip arthroplasty and repair of pelvic fracture since the nerve may become damaged by a bone fraction, undergo iatrogenic damage or become entrapped in the scar tissue.

Femoral nerve

The femoral nerve may become chronically compressed in the area of the inguinal ligament which constitutes the vault of the fibro-osseous canal where the neurovascular bundle travels. The base of the canal is lined with the iliofemoral muscle (placed on the anterior surface of the pubic bone). The entrapment syndrome may be caused by its hyperplasia, inflammation, the presence of hematomas or proliferative changes in this muscle. Posttraumatic lesions (pubic bone fractures) and ilioinguinal bursitis may constitute another reason for compression(2, 4–6).

During the US, apart from cross-sectional area and nerve echogenicity analyzed in relation to the image on the contralateral side, it is essential to assess the presentation of the quadriceps femoris innervated by the femoral nerve. The regressive changes appearing in this area indirectly indicate chronic neuropathy.

Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve may become compressed after it emerges from under the inguinal ligament (Roth syndrome)(7). Its position is very superficial and thus, it is susceptible to irritation resulting from, e.g. too tight clothing. Moreover, at the site where it pierces the fascia lata, it may become damaged at the tension mechanism (abrupt hyperextension of the hip) or the compression mechanism (long standing position). Iatrogenic damage may be caused by femoral joint arthroplasty procedures. Nerve injuries may also take place as a consequence of avulsion fractures of the anterosuperior iliac spine.

When observing the nerve by the lift technique on the longitudinal section, one may detect a sudden enlargement of the diameter and elimination of its bundle-like structure – a spindle-like enlargement (attesting to a local edema). Due to the sensory nature of the nerve, there are no changes in any muscles. However, an important parameter of indirect US evaluation is an attempt to radiate the pain through precise palpation/transducer compression at the site of the visualized pathology.

Obturator nerve

The anterior branch of the obturator nerve travels in the inguinal region. It is placed between the pectineus muscle and the adductor longus and brevis. The branch may be chronically irritated by advanced enthesopathic changes of the adductor longus especially when the inflammation of the pubic symphysis and bone is present(4).

In the US, the nerve will present the features of local edema proximally to the compression site. In an indirect way, its compression may be demonstrated by regressive changes in the innervated muscles (in the adductor longus, brevis and magnus as well as in the gracilis muscle).

Saphenous nerve

Contrary to an extremely rare pathology of the obturator nerve, the dysfunctions of the saphenous nerve occur quite frequently. This nerve travels through the adductor canal with femoral vessels. Then, after piercing the intermuscular septum, together with the sartorius muscle, it heads towards the knee joint and follows further with the saphenous vein. It may become trapped in the postoperative scars or iatrogenically damaged during the collection of the goose's foot tendons for the anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction(8, 9).

The US image of the pathologies of this nerve is identical to the previously described neuropathies, i.e. visible edema, which is recognized by the enlarged diameter, compared with the fragment above the compression site and in the contralateral side. This nerve, similarly to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, is, above all, sensory so an attempt to radiate pain by local compression constitutes an additional parameter.

Common fibular nerve

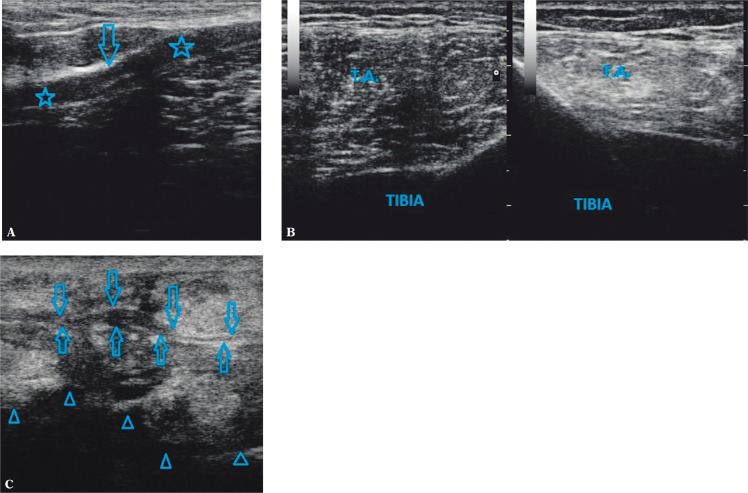

Due to its superficial position, on the neck of the fibula, the common fibular nerve is subject to injuries relatively often (fig. 2 A). Here, it is placed directly on the bone and is covered merely with a layer of skin and subcutaneous tissue. The causes of iatrogenic neuropathies (in the mechanism of compression and ischemia of the nerve trunk) encompass: plaster cast placed inappropriately or long lasting inappropriate position of unconscious patients, e.g. in ICU(5). The nerve is sometimes irritated by ganglia originating in the tibiofibular joint. If the pathology is suspected, the sectional area of the large nerve trunk needs to be specified and compared with the contralateral side as well as with the section above the assessed site. The evidence for neuropathy is the enlargement of this value and disorder in/disappearance of the bundle presentation and the nerve hyperemia.

Fig. 2.

After the damage to the fibular nerve during torsion injury of the knee joint: A. fibular nerve (asterisks) with the features of edema, the lack of bundle presentation, with narrowing and preserved continuity of the epineurium (arrow); B. atrophy of the anterior and lateral groups of crural muscles (T.A. – tibialis anterior muscle, TIBIA – shinbone); C. after a traffic accident, open fracture of the shafts of the crural bones: superficial fibular nerve at the site of piercing the crural fascia (arrows), visible posttraumatic changes in the area of the subcutaneous tissue, muscle tissue as well as uneven bone outlines (triangles)

Deep fibular nerve may become entrapped in several sites, i.e. in superior or inferior tendinous extensor retinacula under which it is located, at the place where it crosses the extensor halluces longus and, more rarely, at the place where it crosses the belly of the extensor halluces brevis. During the examination, one should be careful not to miss the degenerative and proliferative changes of the bone margins of the tarsal and metatarsal articulations, which may irritate the nerve(4, 5, 10).

The damage to the nerve may result from neuropraxia (e.g. during abrupt or excessive plantar bent) or compression (e.g. due to a kick with a dorsal part of the foot or chronic irritation by poorly chosen shoes).

The US evaluation of this slight branch consists in using the lift technique and analyzing its contours and bundle echostructure. At the site of the pathology, the nerve presents the features of edema which is manifested by a sudden change in the diameter. In the case of chronic irritation of the joint, regressive changes take place in the area of the long toe extensor, extensor digitorum longus, tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum brevis muscles(11) (fig. 2 B). The number of muscles involved results from the degree of the nerve pathology.

Superficial fibular nerve most often becomes entrapped as it pierces the crural fascia. This neuropathy may be caused by pathologies of the fascia itself (including scarring changes or hernias) as well as direct injuries (fig. 2 C) and ankle sprains with excessive plantar flexure of the foot or its inversion(12).

Similarly to the pathologies of the deep branch, during the US examination, one should search for the signs of edema of the nerve proximally to the site of compression.

Tibial nerve

The tibial nerve can be chronically compressed by proliferative changes (posttraumatic or degenerative) in the articulative edges of the calcaneus, talus or tibial bones, which constitute the borders of the medial malleolus canal. Apart from the osseous reasons, the compression may also be caused by ganglia appearing in the talocrural joint and subtalar joint or in the tendinous sheaths of the flexor longus muscles. Attention needs to be drawn to the anatomical variants, e.g. low-situated bellies of the flexor longus muscle or additional muscles, e.g. additional flexor digitorum longus(3, 5, 12).

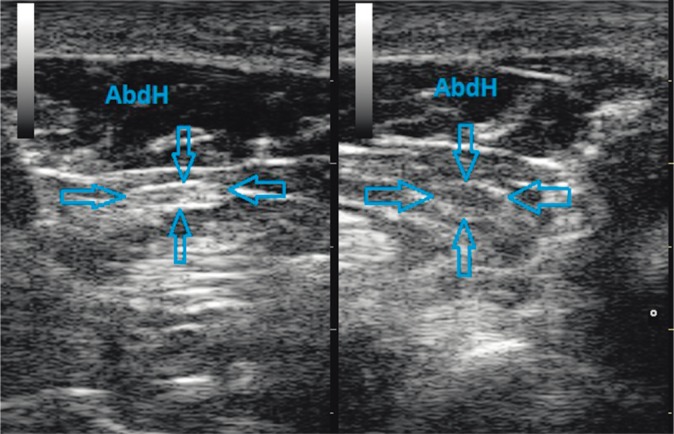

The tibial nerve bifurcates into the medial and lateral branches. The lateral branch of the tibial nerve in its initial section divides into the interior plantar branch which despite being slight and barely visible in the US, is very important. It may be compressed by hyperplastic or scirrhous belly of the abductor hallucis (Baxter's neuropathy)(3). It may also be irritated by the swollen plantar fascia. The medial branch of the tibial nerve may become compressed by the belly of the abductor hallucis, the bellies of flexor digitorum longus and by the flexor hallucis longus (socalled jogger's neuropathy)(3) (fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

On the right: the features of edema of the medial plantar nerve (arrows) in the region of the belly of the abductor hallucis (AbdH); on the left – normal presentation

The direct observation of the nerves on the sole is difficult and unreliable. Thus, the visualization of the muscles innervated by the examined nerves is of particular value. This matters in the case of defective biomechanics of gait or instability of the tarsus, which may lead to functional irritation of the nerves. In such a situation, the ultrasound presents merely discreet changes in the nerves themselves (if they are visualized) and the crucial aspect of the assessment is the regressive changes in the muscles.

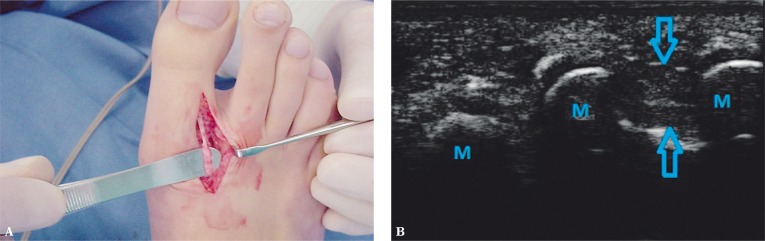

“Morton's neuroma” is a pathology of a peripheral nerve which, histopathologically, has nothing in common with neuroma. It appears on the common plantar digital nerve, most frequently in the II or III web spaces and results from its irritation at the level of the intermetatarsal ligament, which in most cases is caused by inappropriate weight put on the forefoot. The nerve thickens (edema, degeneration, sclerosis). A reactive tissue mass called “Morton's neuroma” is formed (fig. 4 A, B). It is spindle-like in shape and its longer axis is placed along the metatarsals. It presents decreased, heterogeneous echogenicity and increased vascular flow. “Morton's neuroma” may be visualized by applying the transducer to the dorsal part of the foot, additionally pressing against the intermetatarsal space from the plantar part. This maneuver enables the movement of the “neuroma” mass in the dorsal direction. Another test constitutes simultaneous compression on the lateral and medial edges of the foot and the attempt to push the neuroma mass towards the dorsal side. The shift is usually sudden and it is accompanied by a palpable “click”(3, 5).

Fig. 4.

A. Intraoperative image of the “Morton's neuroma”. B. Neuroma during US examination (arrows), the transducer is placed transversely on the dorsal side of the forefoot (M – metatarsal bones)

Sural nerve

Due to its superficial location, the sural nerve may undergo direct injuries, in particular, in the region of the lateral malleolus and tarsus. The nerves may become entrapped in the scars caused by chronic inflammations or repeated repairs of the Achilles tendon and peritendon. It may be chronically irritated during the instability or dislocation of the fibular tendon. It may also become entrapped in scars (fig. 5) or compressed by bone fragments in the cases of tuberosity of the V metatarsal or tarsal bone fractures. The imaging technique and methods of analysis are analogical to those described above.

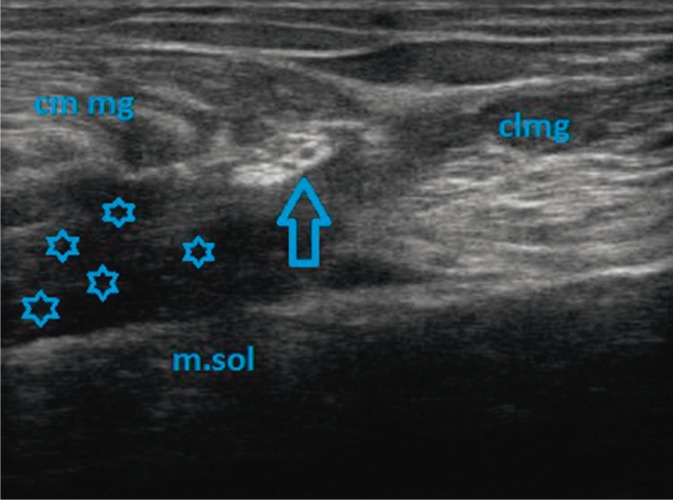

Fig. 5.

The features of the entrapment of sural nerve (arrow) in the scirrhous hematoma (asterisks) after the injury of a core tendon of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle (cm mg). On the right – the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle (clmg) and the soleus muscle (m.sol)

Conclusion

Compression neuropathies belong to the most common pathologies of the peripheral nerves. Ultrasonography is a simple diagnostic tool which constitutes a valuable supplementation of clinical examinations and electrophysiological tests. The direct and indirect features of the ultrasound image of chronic neuropathies, in numerous cases, allow for the determination of the degree and cause of damage and thus, facilitate the process of planning the treatment.

Conflict of interest

Authors do not report any financial or personal links with other persons or organizations, which might affect negatively the content of this publication and/or claim authorship rights to this publication.

References

- 1.Kowalska B, Sudoł-Szopińska I. Ocena ultrasonograficzna wybranych patologii nerwów obwodowych. Część I: Neuropatie uciskowe kończyny górnej – z wyłączeniem zespołu cieśni kanału nadgarstka. J Ultrason. 2012;12:307–318. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banach M, Bogucki A, editors. Kraków: Medycyna Praktyczna; 2003. Zespoły z ucisku – diagnostyka i leczenie. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Windisch G, Braun EM, Anderhuber F. Piriformis muscle: clinical anatomy and consideration of the piriformis syndrome. Surg Radiol Anat. 2007;29:37–45. doi: 10.1007/s00276-006-0169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beltran LS, Bencardino J, Ghazikhanian V, Beltran J. Entrapment neuropathies III: lower limb. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2010;14:501–511. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1268070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bianchi S, Martinoli C. II. Warszawa: Medipage; 2009. Ultrasonografia układu mięśniowo-szkieletowego. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruber H, Peer S, Kovacs P, Marth R, Bodner G. The ultrasonographic appearance of the femoral nerve and cases of iatrogenic impairment. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:163–172. doi: 10.7863/jum.2003.22.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowland LP, editor. II. Wrocław: Elsevier Urban & Partner; 2008. Neurologia Merritta. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lippitt AB. Neuropathy of the saphenous nerve as a cause of knee pain. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1993;52:31–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romanoff ME, Cory PC, Jr, Kalenak A, Keyser GC, Marshall WK. Saphenous nerve entrapment at the adductor canal. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17:478–481. doi: 10.1177/036354658901700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schon LC, Baxter DE. Neuropathies of the foot and ankle in athletes. Clin Sports Med. 1990;9:489–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turaj W, editor. Materiały: A Neurological Journal – Brain. Wrocław: Elsevier Urban & Partner; 2008. Badanie obwodowego układu nerwowego. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delfaut EM, Demondion X, Bieganski A, Thiron MC, Mestdagh H, Cotten A. Imaging of foot and ankle nerve entrapment syndromes: from well-demonstrated to unfamiliar sites. Radiographics. 2003;23:613–623. doi: 10.1148/rg.233025053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]