Abstract

Purpose

We examined the influence of tobacco control program funding, smoke-free air laws, and cigarette prices on young adult smoking outcomes.

Methods

We use a natural experimental design approach that uses the variation in tobacco control policies across states and over time to understand their influence on tobacco outcomes. We combine individual outcome data with annual state-level policy data to conduct multivariable logistic regression models, controlling for an extensive set of sociodemographic factors. The participants are 18- to 25-year-olds from the 2002–2009 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health. The three main outcomes are past-year smoking initiation, and current and established smoking. A current smoker was one who had smoked on at least 1 day in the past 30 days. An established smoker was one who had smoked 1 or more cigarettes in the past 30 days and smoked at least 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime.

Results

Higher levels of tobacco control program funding and greater smoke-free-air law coverage were both associated with declines in current and established smoking (p < .01). Greater coverage of smoke-free air laws was associated with lower past year initiation with marginal significance (p = .058). Higher cigarette prices were not associated with smoking outcomes. Had smoke-free-air law coverage and cumulative tobacco control funding remained at 2002 levels, current and established smoking would have been 5%–7% higher in 2009.

Conclusions

Smoke-free air laws and state tobacco control programs are effective strategies for curbing young adult smoking.

Keywords: Smoking, Young adults, Smoke-free air laws, Cigarette prices, Tobacco control programs

Although 88% of adult smokers initiated smoking before age 18 years [1], public health researchers and the tobacco industry also consider young adulthood to be a formative period for smoking patterns [2]. Leaving the home to live independently gives youth more autonomy to make choices about their lifestyle, including health habits. The tobacco industry has studied young adults with a goal of making smoking socially acceptable [2]. From 1990 to 2005, the prevalence of young adult smoking increased and then decreased; since then, it has been stable [1,3]. Data from the 2000 National Youth Tobacco Survey highlight that age 18 years is still very much a transition period for smoking patterns. In that survey, 21% of 18-year-olds were established smokers who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and had smoked 20 out of the past 30 days [4]. However, an additional 11% had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and had smoked on 1–19 days in the past month (7%) or had not smoked in the past month (4%). Another 40% of 18-year-olds had at least experimented with cigarettes. These statistics suggest that a large proportion of young adults are at risk of becoming established smokers. More recently, data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) show that smoking initiation increased from2002 to 2009 among those aged 18 years and older [5].

Studies have found that some tobacco industry marketing efforts are focused on young adults [2,6] in the form of bar promotions [7], tobacco industry-developed “lifestyle” magazines [8], and advertisements for tobacco products and bar events in the alternative press (e.g., weekly newspapers) with high readership among young adults [9]. Ling and Glantz [2] call for increased tobacco control efforts targeting young adults. They note that tobacco control policies such as cigarette excise tax increases and smoke-free air laws are associated with reductions in smoking prevalence among young adults.

A few national studies have examined the influence of cigarette prices and smoke-free air policies on smoking among young adults. Farrelly et al. found that higher cigarette prices were associated with lower smoking prevalence and decreased daily consumption among young adults aged 18 to 24 years: a 10% increase in price was associated with a 3% decrease in smoking prevalence [10]. In a similar study, Farrelly et al. found that a 10% increase in price was associated with a 2.7% to 3.2% decrease in prevalence among U.S. 18- to 24-year-olds from the Tobacco Use Supplements to the Current Population Surveys [11]. Based on longitudinal follow-up surveys of high school seniors from the Monitoring the Future Surveys, Tauras found that higher prices discouraged progression to heavier smoking [12] and increased cessation among young adults [13]. Tauras found that smoke-free workplace laws discourage young adults from progressing to heavier smoking [12]. Another study showed that 100% smoke-free workplace voluntary policies are associated with decreased smoking prevalence and consumption among young adults aged 19 to 24 years [14]. Finally, another study examined the effect of funding for tobacco control programs on young adult smoking prevalence [11].

A recent study found evidence of a sustained and steadily increasing long-run impact of tobacco control program spending on cigarette sales in states [15]. Farrelly and colleagues found that cumulative expenditures for state tobacco control programs was associated with a decreased prevalence of smoking among 18- to 24-year-olds [11].

The current paper is the first study that we are aware of to examine simultaneously the influence of cigarette prices, smoke-free air laws, and funding for state tobacco control programs on young adult smoking behaviors. Our analysis merges data on state-level tobacco control policies with data from the 2002–2009 NSDUH, an annual household-based survey with national and state representative samples of young adults aged 18 to 25 years.

Methods

NSDUH is a national survey of illicit drug, alcohol, and tobacco use by the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population aged 12 years or older that has been conducted since 1971. The 2002–2009 NSDUH employed a state-based design with an independent, multistage area probability sample within each state and the District of Columbia. The design oversampled youths and young adults, so that each state’s sample was approximately equally distributed among three age groups: 12 to 17 years, 18 to 25 years, and 26 years or older. Response rates for 18- to 25-year-olds ranged from 80%–85% during the study period. This study focuses on young adults aged 18 to 25 years. The NSDUH data collection protocol was approved by RTI International’s institutional review board.

Smoking outcomes

We examined three smoking outcomes: (1) never smokers who initiated smoking in the past year; (2) current smokers; and (3) established smokers. Each outcome variable was a dichotomous indicator equal to 1 if the respondent met the criteria for the given outcome, and 0 otherwise. Young adults were considered to have initiated smoking in the past year if the date of reported first cigarette use was within 12 months from the date of the survey interview. A current smoker was one who had smoked on at least 1 day in the past 30 days. The common question for defining current smoking among adults (“Do you now smoke cigarettes every day, some days, or not at all?”) was not available in the 2002–2009 NSDUH. An established smoker was one who had smoked one or more cigarettes in the past 30 days and smoked at least 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime.

State tobacco control programs and policies

We examined the influence on smoking outcomes of annual measures of state average cigarette prices, cumulative state funding for tobacco control programs, and the percentage of the state population covered by smoke-free air laws. The state average annual retail price per pack of cigarettes came from The Tax Burden on Tobacco [16].

Following previous analyses of tobacco control programs [11,17] we constructed a measure of per capita cumulative funding for state tobacco control programs using the state’s total population as the denominator. To compute cumulative funding, each year’s annual funding was added to all previous years of funding (beginning in 1985 and ending in 2009), which were discounted at a rate of 25% per year [11,15]. This measure was then converted to per capita terms by dividing state cumulative funding by the state’s total population. Cumulative funding was used to measure the persistence of investment in tobacco control programs such that funding for tobacco control in a given year continued to affect smoking outcomes in subsequent years. Funding includes state excise tax funding and general funds designated for tobacco control programs as well as funding from national sources, such as the National Cancer Institute’s American Stop Smoking Intervention Study (ASSIST), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Initiatives to Mobilize for the Prevention and Control of Tobacco Use (IMPACT) program, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s SmokeLess States program, and the CDC’s National Tobacco Control Program, which combined ASSIST and IMPACT in 1999. Data on state funding for tobacco control come from a database maintained by RTI International. These data are collected from state reports and communication with state tobacco control programs. The data reflect actual expenditures, when available; otherwise, we include appropriations. For simplicity, we refer to tobacco control funding throughout. For both state tobacco control program cumulative funding and cigarette prices, we adjusted for inflation using the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index.

Our measure of smoke-free air laws was represented by the annual percentage of the state population covered by state or local smoke-free air laws that ban smoking in at least one of the following locations: workplaces, restaurants, or bars [18]. State and municipality population data were obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau [19]. In each year of the study period, the population of the municipalities with smoke-free air laws for workplaces, restaurants, or bars was summed and the total divided by the annual state population to calculate the percentage of the state that is covered by smoke-free air laws.

Control variables

Individual-level control variables included categorical indicators for the following basic demographic characteristics: gender (male, female); race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic 2 or more races, or Hispanic); age (18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, or 25 years); and U.S.-born (yes, no).We controlled for annual family income (<$20,000; $20,000 to $49,999; $50,000 to $74,999; or ≥$75,000); marital status (never married; widowed, divorced, or separated; or married); health insurance coverage (private-only, Medicaid/CHIP-only, Medicaid+ private/other, or no insurance); county of residence (metropolitan, nonmetropolitan, or rural); high school graduate (yes, no); employment status (full-time, part-time, unemployed, other); and an indicator for whether or not others were present during the interview more than one third of the time (yes, no).

Three variables were included to control for thrill-seeking or risk-taking behavior, which has been shown to be correlated with youth smoking [20]. Because of a nontrivial number of missing values for these variables, we included an unknown category to reduce the number of respondents dropped from the analysis: (1) gets a kick out of doing dangerous things; (2) likes to test self by doing dangerous things (both coded as never; seldom, sometimes, always; or unknown); and (3) wears a seatbelt riding in front passenger seat of car (coded as always; never, sometimes, seldom; or unknown). Religiosity has also been shown to be associated with smoking [21]. Three variables controlled for religiosity and included an unknown category: (1) number of times attended religious services in the past year (coded as none, 1–24, 25 or more, or unknown); (2) religious beliefs influence life decisions (coded as strongly agree/agree, disagree/strongly disagree, or unknown); and (3) important for friends to share religious beliefs (coded as strongly agree/agree, disagree/strongly disagree, or unknown).

We included the 2002 state-level prevalence of current smoking among adults aged 25 years or older based on smoking in the past 30 days to account for preexisting differences in social norms at baseline. States with a higher prevalence of smoking among adults aged 25 years or older were assumed to have a more favorable attitude toward smoking, which may be correlated with the strength of tobacco control policies in the state and also the prevalence of young adult smoking. The prevalence of smoking among adults aged 25 or older in 2002 was merged to each respondent by state and was, therefore, constant for all years of the study. To account for secular trends in the outcomes, we included a linear time trend in each of the models.

Statistical analysis

After presenting descriptive statistics for the three smoking outcome variables and three tobacco control policies from 2002 to 2009, we estimated multivariate logistic regression models because all of the outcome variables are dichotomous. The descriptive statistics compare the sample averages using t-tests. The state policy variables were summarized after they were merged to the individual-level data by state, year, and quarter; hence, they are population-weighted means. The final sample size for the models of current smoking and established smoking was 181,304, with 184 observations excluded due to missing data on one or more of the variables in the model. For the past year initiation model, the final sample size was 62,263, with 92 observations excluded due to missing data. We used SAS and SUDAAN for all analyses to account for NSDUH’s complex survey design and sampling weights [22,23].

To illustrate the magnitude of the key variables, we used the results of the regression analysis to predict what the trends in smoking outcomes would have been had the level of tobacco control program funding and policies stayed constant at 2002 levels. We also calculated normalized measures of effect sizes (i.e., elasticities) that give the percentage change in the outcome for a given percentage change in the policy variable.

Results

The trends in our key outcomes (Table 1) show that the prevalence of current and established smoking was lower in 2009 than in 2002 (p < .01), although past year initiation increased (p < .01). Over this same time, the three key tobacco control policy variables increased considerably. The U.S. average percentage of the state population covered by smoke-free air laws more than quadrupled from 15.4% to 71.1%. Inflation-adjusted per capita cumulative funding for state tobacco control programs and the state average retail price per pack of cigarettes increased by 28% and 44% in relative terms, respectively.

Table 1.

Trends in smoking outcomes among 18- to 25-year-olds and state tobacco control policies in the United States, 2002–2009

| Variable | 2002 | 2009 | Relative % change [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking outcomes | |||

| Prior year initiation rate among never smokersa | 6.7% | 8.6% | 28.0 [10.5, 45.4] |

| Current smoking prevalenceb | 40.8% | 35.8% | −12.1 [−8.9, −15.4] |

| Established smoking prevalencec | 34.5% | 28.4% | −17.9 [−14.3, −21.5] |

| State tobacco control policies | |||

| Percentage of the state population covered by smoke-free air laws | 15.4% | 71.1% | 362.3 [351.2, 362.3] |

| Per capita cumulative funding for state tobacco control programs | $6.92 | $8.85 | 28.0 [24.3, 31.7] |

| State average retail price per pack of cigarettes | $3.85 | $5.55 | 44.2 [43.3, 45.0] |

Note: The changes in smoking outcomes between 2002 and 2009 are all statistically significant (p < .01).

Prior year initiation is defined as first trying cigarettes in the 12 months prior to the interview.

Current smoking is defined as having smoked 1 or more cigarettes in the past 30 days.

Established smoking is defined as having smoked 1 or more cigarettes in the past 30 days and smoked at least 100 cigarettes in lifetime.

The results of multivariate logistic regressions indicate that smoke-free air laws and funding for tobacco control programs were associated with the prevalence of current and established smoking (Table 2). Higher levels of tobacco control funding were marginally associated with lower levels of initiation (p = .058), while smoke-free air laws were not associated with smoking initiation. Cigarette prices were not associated with any of the three smoking outcomes in this age group. The results indicate that a doubling of the percentage of the population covered by smoke-free air laws would have led to a 3.2% relative decrease in current smoking and a 4.5% relative decrease in established smoking over the study time period. Likewise, a doubling of cumulative funding for state tobacco control programs would have led to relative decreases in current and established smoking by 3.2% and 3.6% respectively.

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression results showing effects of state tobacco control policy variables on young adult smoking outcomes, NSDUH, 2002–2009

| Independent variable and effecta | Prior year initiationb | Current smokingc | Established smokingd |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of the state population covered by smoke-free air laws | .999 (.998, 1.000) [−.029] | .999 (.998, .999) [−.032] | .998 (.998, .999) [−.045] |

| Per capita cumulative funding for state tobacco control programs | .994 (.989, 1.000) [−.040] | .992 (.990, .994) [−.034] | .992 (.990, .995) [−.036] |

| State average retail price per pack of cigarettes | .961 (.911, 1.014) [−.150] | 1.008 (.990, 1.026) [.018] | 1.017 (.996, 1.037) [.040] |

| Gets a kick out of doing dangerous things | |||

| Seldom, sometimes, or always | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) |

| Never | .614 (.540, .698) | .643 (.617, .670) | .650 (.622, .679) |

| Unknown | .533 (.185, 1.541) | .510 (.362, .718) | .519 (.353, .762) |

| Likes to test self by doing risky things | |||

| Seldom, sometimes, or always | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) |

| Never | .805 (.711, .912) | .842 (.808, .877) | .857 (.820, .896) |

| Unknown | .485 (.055, 4.249) | .813 (.529, 1.252) | .853 (.540, 1.347) |

| Wears seatbelt riding in front passenger seat of car | |||

| Always | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) |

| Never, seldom, or sometimes | 1.186 (1.074, 1.309) | 1.661 (1.612, 1.712) | 1.704 (1.651, 1.759) |

| Unknown | 1.191 (.120, 11.792) | .912 (.523, 1.589) | .678 (.391, 1.173) |

| Number of times attended religious services in the past year | |||

| 0 | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) |

| 1–24 | 1.131 (1.023, 1.250) | .879 (.851, .908) | .817 (.791, .843) |

| 25+ | .687 (.605, .779) | .434 (.414, .454) | .372 (.354, .392) |

| Unknown | 1.186 (.678, 2.075) | .910 (.760, 1.090) | .870 (.718, 1.055) |

| Religious beliefs influence life decisions | |||

| Strongly agree/agree | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 1.159 (1.050, 1.278) | 1.210 (1.171, 1.249) | 1.198 (1.159, 1.238) |

| Unknown | .987 (.598, 1.629) | 1.207 (1.026, 1.419) | 1.219 (1.021, 1.455) |

| Important for friends to share religious beliefs | |||

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) |

| Strongly agree/agree | .813 (.722, .915) | .723 (.696, .751) | .724 (.695, .755) |

| Unknown | .995 (.627, 1.579) | 1.079 (.912, 1.276) | 1.056 (.881, 1.265) |

| High school graduate | |||

| Yes | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) |

| No | 1.114 (.931, 1.333) | 1.959 (1.869, 2.053) | 2.068 (1.968, 2.174) |

| Employment status | |||

| Full-time | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) |

| Part-time | .919 (.827, 1.021) | .776 (.749, .803) | .0728 (.702, .756) |

| Unemployed | 1.051 (.897, 1.232) | 1.184 (1.124, 1.247) | 1.183 (1.121, 1.248) |

| Other | .749 (.659, .850) | .734 (.706, .764) | .728 (.698, .759) |

| Family income | |||

| <$20,000 | 1.259 (1.130, 1.402) | 1.054 (1.017, 1.092) | .971 (.935, 1.008) |

| $20,000–$49,999 | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 1.055 (.918, 1.211) | .899 (.861, .938) | .903 (.864, .944) |

| ≥$75,000 | .972 (.861, 1.097) | .891 (.856, .928) | .861 (.826, .899) |

| Health insurance | |||

| Medicaid/CHIP only | .923 (.790, 1.079) | 1.519 (1.446, 1.596) | 1.781 (1.688, 1.878) |

| Private only | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) |

| No insurance | .981 (0868, 1.108) | 1.669 (1.611, 1.729) | 1.861 (1.795, 1.931) |

| Medicaid, private, and/or other | .976 (.830, 1.147) | 1.259 (1.190, 1.332) | 1.315 (1.238, 1.397) |

| Marital status | |||

| Never married | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) |

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | 1.022 (.584, 1.786) | 1.745 (1.591, 1.914) | 1.816 (1.655, 1.994) |

| Married | .668 (.529, .844) | .781 (.746, .817) | .862 (.823, .903) |

| Prevalence of smoking in 2002 among adults aged 25 or older | .446 (.148, 1.339) | 4.915 (3.271, 7.385) | 8.796 (5.762, 13.426) |

Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) [Elasticity]. All models also include an intercept, linear time trend, and indicator variables for gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black or African-American, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic 2 or more races, and Hispanic), age (from 18 to 25), U.S.-born, others present during interview more than one third of the time, and county of residence (metropolitan, nonmetropolitan, rural).

NSDUH = National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Respondents with unknown information for 1 or more covariates were excluded from the analysis. An unknown/missing data category was included for several variables to reduce the number of respondents excluded from the analysis.

Prior year initiation is defined as first trying cigarettes in the 12 months prior to the interview.

Current smoking is defined as having smoked 1 or more cigarettes in the past 30 days.

Established smoking is defined as having smoked 1 or more cigarettes in the past 30 days and smoked at least 100 cigarettes in lifetime.

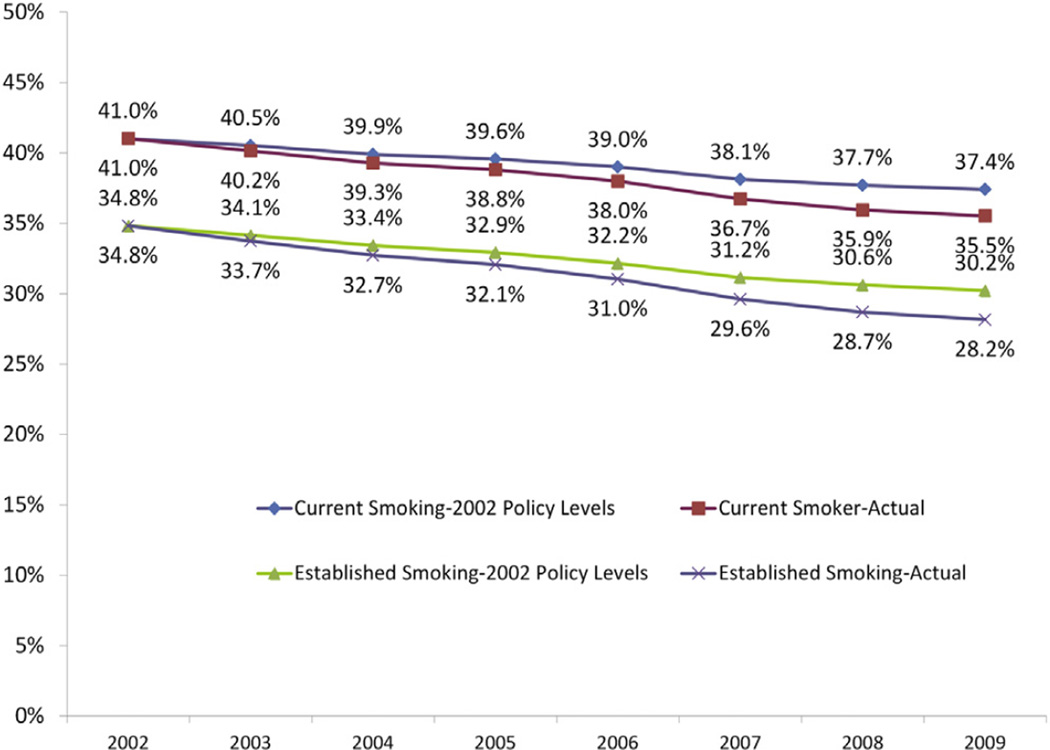

To further illustrate the effect of smoke-free air laws and funding for tobacco control programs, we predicted trends in current smoking and established smoking from 2002 to 2009 holding these policies at 2002 levels. Figure 1 illustrates these trends and shows that the predicted prevalence of current and established smoking would have been 5.3% and 7.4% higher in relative terms than the predicted trends with the actual policy variable values in 2009.

Figure 1.

Current and established smoking prevalence actual trends and predicated trends holding tobacco control policies at 2002 levels.

Risk taking, wearing seat belts, and religiosity were all associated with all three smoking outcomes. With respect to sociodemographic factors, education, employment, income, health insurance, and marital status were all associated with current and established smoking. Those without a high school diploma, current employment, or private health insurance had increased odds of being a current or established smoker, as did those who were divorced, widowed, or separated. Past year initiation was positively associated with having an annual income of less than $20,000 and negatively associated with being married compared with those who had never been married. Having an annual income of less than $20,000 was positively associated with prior year initiation and current smoking, but not with established smoking.

Discussion

From 2002 to 2009, the prevalence of current and established smoking declined by 12% and almost 18%, respectively. However, over this same time, past year initiation increased by 28% (from 6.7% to 8.6%). Given that current smoking rates declined by nearly one third (from 13.0% to 8.9%) among 12- to 17-year-olds during this time period [5], this suggests that smoking initiation may be delayed for some youth, a finding that is consistent with Lantz [1]. From 2002 to 2009, smoke-free air laws became very common, and average state-level funding for tobacco control programs and cigarette prices increased. What is unique to the current study is that we simultaneously examined the effects these three tobacco control policies had on young adult smoking, controlling for a wide range of potential confounding influences.

Consistent with Tauras [12], we observed that increases in smoke-free air laws were associated with decreased young adult current and established smoking. However, there was no association with past year initiation. We used a liberal definition of population coverage of smoke-free air laws by including the areas covered by at least one of the following locales: workplaces, restaurants, or bars. A more comprehensive measure that required all three locations was significantly associated with all three outcomes in bivariate analyses and multivariable analyses that excluded cigarette prices and tobacco control funding. However, in models that included all three measures, this more comprehensive measure was not statistically significantly associated with any of the three smoking outcomes. It is possible that the correlation between these three tobacco control policies is too great to estimate separately the effect of this more stringent measure of smoke-free air laws beyond the influence of cigarette prices and tobacco control program funding. This is likely given that many tobacco control programs engage in activities aimed at educating the public about the benefits of smoke-free environments (e.g., media campaigns, policymaker education) [24].

Similar to Farrelly et al., we found that increases in funding for state tobacco control programs are associated with decreases in current and established smoking [11], but we found no association with past year initiation. In contrast to previous studies [11,14], we found no effect of higher cigarette prices on smoking among young adults. The lack of an association between cigarette prices with smoking outcomes is puzzling because most studies have found youth and young adults to be more price-responsive than older adults [1]. However, the tobacco industry spends billions on price-related promotions to counter effects of price increases because of their own research on the price sensitivity of young consumers [25]. It is possible that tobacco marketing heavily targeted to young adults [2,6,25] counteracts increases in cigarette prices resulting from increased cigarette excise taxes. This would be especially true if, as some have found, price promotions are more common in high-tax states [26]. It is also possible that young adults are opting for discount cigarettes or low- or un-taxed sources (e.g., online, Native American reservations) [27]. Therefore, our aggregate measure of cigarette prices may not adequately reflect prices paid by young adults.

The current study provides additional support to the idea that smoke-free air laws and funding for state tobacco control programs have been effective in reducing young adult smoking. These findings, along with evidence that tobacco industry promotions and marketing have been aimed at young adults, provides a strong rationale for investing in state tobacco control programs and implementing policies that change the social environment in which smoking occurs [1].

In this study, we found that if tobacco control policies had remained at 2002 levels (rather than increasing), the prevalence of current and established smoking would have been roughly 5% (638,019) to 7% (671,599) higher, respectively, in 2009. This translates to an additional 638,019 current and 671,599 established smokers. Given the relatively high rates of smoking in this age group compared with other ages [5], our findings highlight the salience of smoke-free air laws and tobacco control programs to curbing young adult smoking.

Despite the strong influence of tobacco policies on young adult current and established smoking, we found no association between these policies and past year initiation. This finding may indicate that these policies are ineffective in curbing experimentation in this age group but are effective in preventing regular use. It is also possible that there was insufficient variation in this outcome during the study period to fully understand the influence of tobacco control policies on past year initiation. Although the relative increase in past year initiation was large over the study period (28%), the absolute change was modest compared with the other outcomes (from 6.7% to 8.6%), providing less statistical power for detecting effects of programs and policies. This is consistent with the fact that only income and marital status were associated with past year initiation, while education, employment, income, health insurance, and marital status were all strongly associated with both current and established smoking.

Our study has several limitations. First, the policy measures we examined are aggregate, state-level measures and may not adequately reflect the young adult-specific community context, given that there can be variation within a state. For example, it is possible that our state aggregate cigarette price measure may not adequately reflect prices paid by young adults in different communities in the state. This is possible if the brand preferences of young adult smokers in some communities are significantly different than those of the overall population. Second, funding for state tobacco control programs is a global measure of all tobacco control activities. Ideally, we would rather have specific measures of effective tobacco control activities because these would be more proximal to the outcomes examined in this study (e.g., exposure to media campaigns, community mobilization efforts). Finally, the time frame for this study is relatively short, which limits the amount of variation in outcomes and tobacco control policy variables and thus our ability to detect effects.

Despite these limitations, this study shows that funding for tobacco control programs and policies is associated with decreases in young adult current and established smoking. Smoke-free air laws and state tobacco control programs are effective strategies for curbing young adult smoking. Given the tobacco industry’s marketing and promotion aimed at young adults and the strong evidence base for tobacco control programs and smoke-free air laws, continuous and sufficient funding for state and national tobacco control programs can have a critical impact on curbing smoking at this critical transitional life stage. Although we did not find that higher cigarette prices were associated with decreased smoking, other studies that have covered a longer time frame have found young adults and youth to be more responsive to price increases than older adults. Our finding points to the need to identify and validate measures of the recent purchasing patterns and cigarette prices paid by young adults [1].

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

This study provides unique insights into cigarette smoking during a critical life stage for establishing long-term health habits. We demonstrate that funding for state tobacco control programs and smoke-free air laws have been effective measures for reducing smoking among young adults.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank David Heller of RTI International for reviewing the statistical analyses.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Office on Smoking and Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and the conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: Evidence from industry documents. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:908–916. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson DE, Mowery P, Jackson K. The prevention of cigarette smoking: Long-term national trends in adolescent and young adult smoking. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:905–915. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mowery PD, Farrelly MC, Haviland ML. Progression to established smoking among U. S. youths. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:331–337. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2009 national survey on drug use and health, volume I: Summary of national findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biener L, Albers AB. Young adults: Vulnerable new targets of tobacco marketing. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:326–330. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sepe E, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Smooth moves: Bar and nightclub tobacco promotions that target young adults. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:414–419. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortese DK, Lewis MJ, Ling PM. Tobacco industry lifestyle magazines targeted to young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:268–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sepe E, Glantz SA. Bar and club tobacco promotions in the alternative press: Targeting young adults. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:75–78. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farrelly MC, Bray JW, Pechacek T. Response by adults to increases in cigarette prices by sociodemographic characteristics. South Econ J. 2001;68:156–165. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrelly MC, Pechacek TF, Thomas KY. The impact of tobacco control programs on adult smoking. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:304–309. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.106377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tauras JA. Can public policy deter smoking escalation among young adults? J Policy Anal Manage. 2005;24:771–784. doi: 10.1002/pam.20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tauras JA. Public policy and smoking cessation among young adults in the United States. Health Policy. 2004;68:321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farrelly MC, Evans WN, Sfekas AE. The impact of workplace smoking bans: Results from a national survey. Tob Control. 1999;8:272–277. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.3.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chattopadhyay S, Pieper D. Does spending more on tobacco control programs make economic sense? An incremental benefit-cost analysis using panel data. Contemp Econ Policy. 2012;30:430–447. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orzechowski W, Walker R. The tax burden on tobacco. Arlington, VA: Historical Compilation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farrelly MC, Pechacek TF, Chaloupka FJ. The impact of tobacco control program expenditures on aggregate cigarette sales: 1981–2000. J Health Econ. 2003;22:843–859. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(03)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation. Chronological table of U.S. population protected by 100% smokefree state or local laws. 2010 Available at: http://www.no-smoke.org/pdf/EffectivePopulationList.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Census Bureau. Population Division, CO-EST2009-alldata: Annual resident population estimates, estimated components of resident population change, and rates of the components of resident population change for states and counties: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2009. 2010 Available at: http://www.census.gov/popest/counties/files/CO-EST2009-alldata.pdf.

- 20.Zuckerman M, Ball S, Black J. Influences of sensation seeking, gender, risk appraisal, and situational motivation on smoking. Addict Behav. 1990;15:209–220. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nonnemaker JM, McNeely CA, Blum RW. Public and private domains of religiosity and adolescent smoking transitions. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:3084–3095. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.RTI International. SUDAAN®, Release 10.0 [computer software] Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; [Google Scholar]

- 23.SAS Institute. SAS/STAT User’s Guide: Version 9. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best practices for comprehensive tobacco control programs—2007. Atlanta, GA: Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U. S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaloupka FJ, Cummings KM, Morley CP. Tax, price and cigarette smoking: Evidence from the tobacco documents and implications for tobacco company marketing strategies. Tob Control. 2002;11(Suppl.1):I62–I72. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loomis BR, Farrelly MC, Mann NH. The association of retail promotions for cigarettes with the Master Settlement Agreement, tobacco control programmes and cigarette excise taxes. Tob Control. 2006;15:458–463. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.016378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cantrell J, Shelley D, Fahs M. Changes in tobacco use behavior and purchasing patterns after a $3.00 cigarettes tax increase in NYC. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:135–146. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]