Significance

The ability to continuously mix complex fluids at the microscale depends on their flow rate, rheology, and mixing rate. New scaling relationships between mixer dimensions and operating conditions are derived and experimentally verified to create a framework for designing active microfluidic mixers that can efficiently homogenize a wide range of materials. Based on this understanding, active mixing printheads are designed and implemented for multimaterial printing of 3D architectures whose local composition and properties can be programmably tailored.

Keywords: microfluidic mixing, yield stress fluids, 3D printing, graded materials

Abstract

Mixing of complex fluids at low Reynolds number is fundamental for a broad range of applications, including materials assembly, microfluidics, and biomedical devices. Of these materials, yield stress fluids (and gels) pose the most significant challenges, especially when they must be mixed in low volumes over short timescales. New scaling relationships between mixer dimensions and operating conditions are derived and experimentally verified to create a framework for designing active microfluidic mixers that can efficiently homogenize a wide range of complex fluids. Active mixing printheads are then designed and implemented for multimaterial 3D printing of viscoelastic inks with programmable control of local composition.

Mixing at low Reynolds number is important for many processes (1, 2) from bioassays (3) and medical analysis (4), to materials synthesis (5) and patterning (6). Microfluidic devices that passively mix small fluid volumes (7–9) via chaotic advection or secondary flows have been implemented for many targeted applications (10–12). Passive mixers are simple and operate with no moving parts, but their mixing efficiency is strongly coupled to flow rate and geometry. Moreover, they are typically suited only for low-viscosity fluids containing diffusive species, such as colloidal particles (13). Whereas elastic instabilities have been shown to drive mixing of weakly viscoelastic polymer solutions in microfluidic devices (14), there is growing interest in continuous mixing of strongly viscoelastic materials, i.e., yield stress fluids, in microchannels, which until now has only been demonstrated at the macroscale (15, 16). The ability to uniformly and rapidly mix such liquids at the microscale would open new avenues for myriad applications, including additive manufacturing (17, 18). For example, concentrated viscoelastic inks are patterned by direct ink writing, an extrusion-based 3D printing method (19). To date, this flexible printing method has been used to create ceramic (20, 21), polymeric (22), metallic (23), and composite (24) architectures as well as vascularized tissues (25). In each case, the ink composition remains constant during the printing process. The ability to create more complex architectures with local compositional gradients is cumbersome at best, requiring a coordinated printpath between multiple individually addressable printheads––each of which contains a different ink (25).

To overcome this challenge, we design, characterize, and exploit the mixing efficiency of an active mixer that homogenizes multiple materials at the microscale. To understand the relative advantages of active mixing, we derive and experimentally validate scaling relationships that are consistent with existing theory for passive mixers (10). To our knowledge, this is the first quantitative explanation of the mechanism by which an active microfluidic mixer decouples the intensity of the chaotic advection from the flow rate. This unique feature enables viscoelastic materials to be mixed over a wide range of flow rates on short timescales in microliter volumes. Finally, we demonstrate the versatility of the active mixer to achieve “on-the-fly” local control of material composition and properties via multimaterial 3D printing.

Active and Passive Mixing in Microfluidic Devices

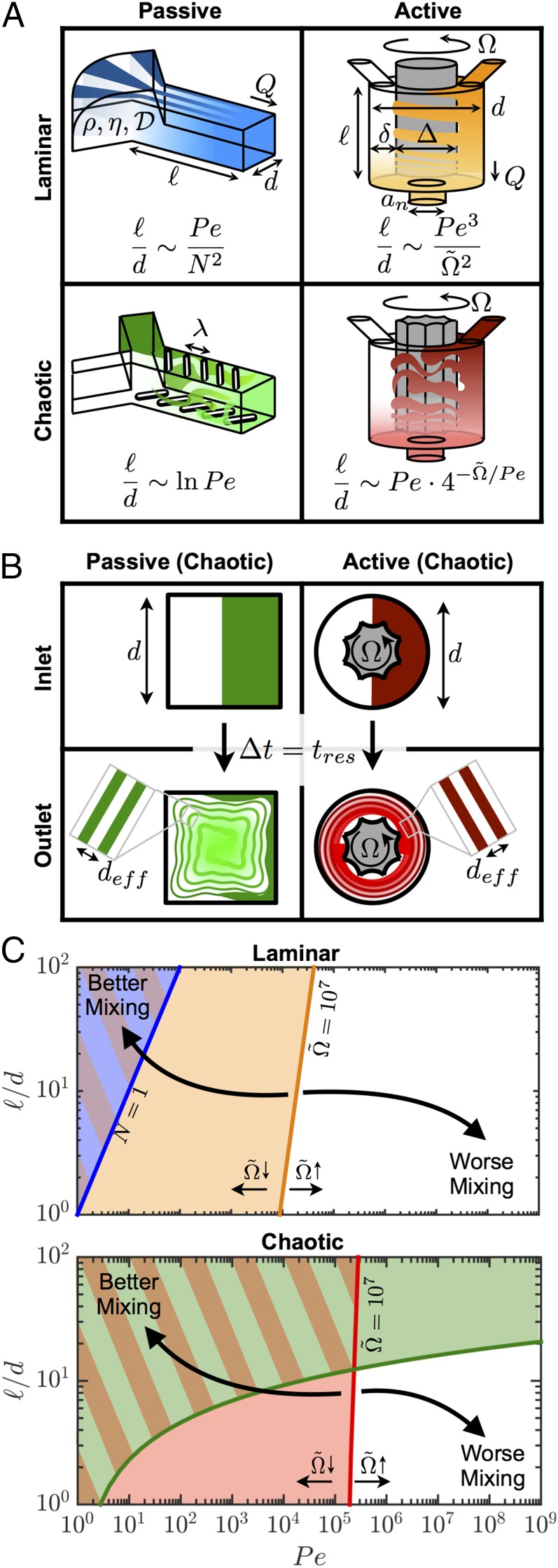

To compare mixing approaches, we begin with the simplest case: Newtonian fluids and Brownian particles. To mix these fluids, the minimum residence timescale of a fluid element in the mixer must exceed the time required for the species to diffuse over a characteristic distance set by the flow dynamics within the mixer. In a prototypical Y-junction (smooth-wall) passive mixer, two streams converge into a single rectilinear channel of length and hydraulic diameter . Hence, , where is the net volumetric flow rate through the device, and , where is the diffusion coefficient of the particles. Efficient mixing requires that , where the Péclet number is defined as . For typical conditions of , , , and , a prohibitively long microchannel () is required to achieve efficient mixing. To reduce this mixing length for a fixed , it is necessary to enhance the interdigitation between streamlines of the two materials. Interdigitation can be achieved by multilamellar mixers (2) with layers (Fig. 1A), for which

| [1] |

Alternatively, in a grooved-wall passive mixer (Fig. 1A), interdigitation is achieved by chaotic advection induced by obstructions to the flow, for which the effective mixing distance is , where is proportional to the number of grooves with spacing λ on the walls of the mixer. The mixing timescale is therefore , and it can be shown that (10)

| [2] |

Hence, interdigitation and chaotic advection, shown schematically in Fig. 1B, can dramatically reduce mixing length for low viscosity fluids (e.g., aqueous solutions). More sophisticated analyses (26–28) show that in the final stages of the homogenization process due to wall effects, but because our subsequent analysis is intended to be only of leading order, the use of the Ranz model in deriving the mixing timescale is appropriate (29). In both cases, chaotic advection yields a sublinear scaling between channel length and flow rate. However, a major drawback of passive mixers is that streamwise interdigitation is controlled only by the geometry and flow rate; hence, for highly viscous liquids (low , high ), very long channels () are required, leading to prohibitively large pressure drops (Eq. S1 and Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic illustrations of the mixing nozzle designs for passive and active mixers using laminar and chaotic flow. (B) Interdigitation of the dyed and undyed mixing streams at the outlet of each mixer. (C) Operating map for mixing nozzles. The boundaries between regimes of good (shaded) and poor (unshaded) mixing are given by the curves whose color corresponds to the mixer type in A. The position of the boundary for the active mixer corresponds to and can be moved by changing impeller speed. The curves for the active mixer have been calculated with .

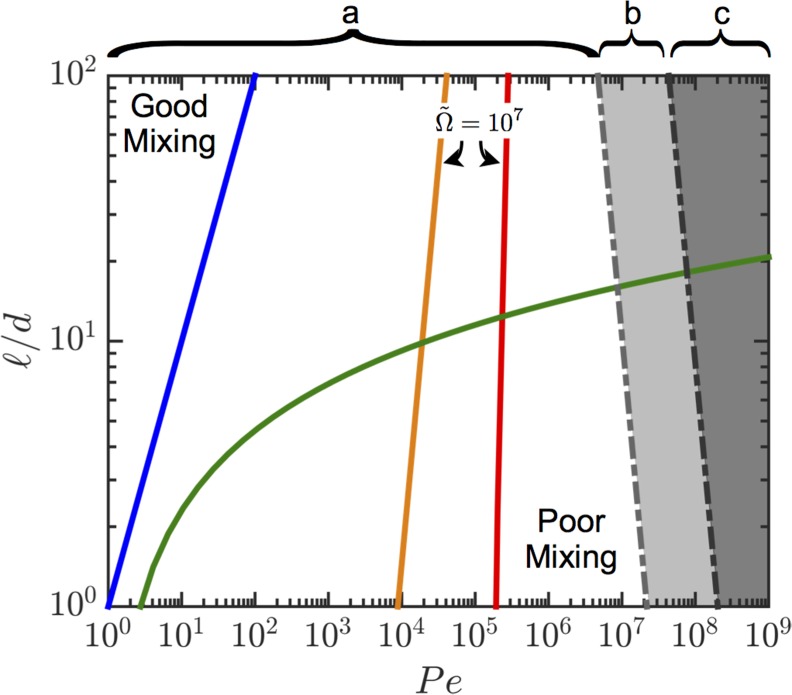

Fig. S1.

Operating map for mixing nozzles accounting for the accessible range of flow rates for a given maximum pressure drop (based on properties for glycerol in Table S1 and assuming Pa, set mL/min and ). (A) Accessible regime, (B) accessible only for the passive mixers, (C) inaccessible regime. The boundaries between regimes of good and poor mixing are given by the dashed curves for the passive mixers and solid curves corresponding to constant dimensionless impeller speeds with the active mixer. The curves for the active mixer have been calculated with and .

A more effective device is an active mixer (30), which controls the interdigitation and shear rate independently from the operating flow rate and channel geometry, thereby minimizing volume, mixing time, and pressure drop. A prototypical impeller-based active mixer has length , characteristic diameter , outlet diameter , and impeller diameter rotating at angular velocity (Fig. 1A). To convey the idea that passive and active mixers can be constructed from the same constituent channel geometry, the variables and are used interchangeably for both mixer types. The residence time is and the fluid travels through a narrow gap . The effective diffusion distance is given by , where is proportional to the number of revolutions completed by the impeller while a fluid element resides in the mixer. By equating the two timescales, it can be shown that

| [3] |

where the dimensionless rotation rate is and . If the impeller is grooved and induces chaotic advection within the mixer, then the effective diffusion length is , in which case

| [4] |

Unlike the passive mixing equations, Eqs. 3 and 4 contain the third independent parameter that controls the level of interdigitation between the inlet fluid streams (Fig. 1B), which is the key new attribute in the scaling analysis of the active mixer.

A simple framework can be developed using Eqs. 1–4 to compare the mixing efficiency of each mixer (Fig. 1C). The boundaries between regimes of good and poor mixing lie to the left and right, respectively, of a given contour. For a given nozzle diameter, a low is preferable to reduce its “dead” volume, thereby enabling rapid switching between different material compositions. Likewise, for a fixed nozzle volume and flow rate, a low aspect ratio is desirable to reduce the pressure drop across the nozzle (SI Text and Fig. S1). We find that only an active mixer (Fig. 2) operating at sufficiently high impeller speeds is capable of mixing at low and high .

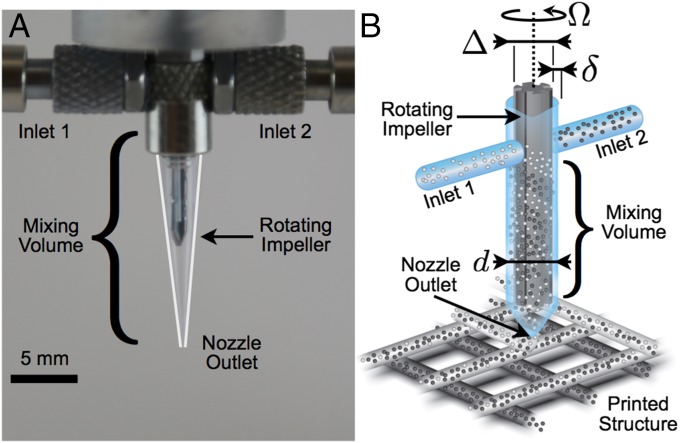

Fig. 2.

(A) Optical image of the impeller-based active mixer. White lines have been added to accentuate the edges of the transparent nozzle tip. (B) Schematic illustration of the mixing nozzle in operation for 3D printing of two inks with particles of different color. Each fluid enters the mixing chamber of diameter through a separate inlet and is homogenized in a narrow gap of width by an impeller of diameter rotating at a constant rate .

SI Text

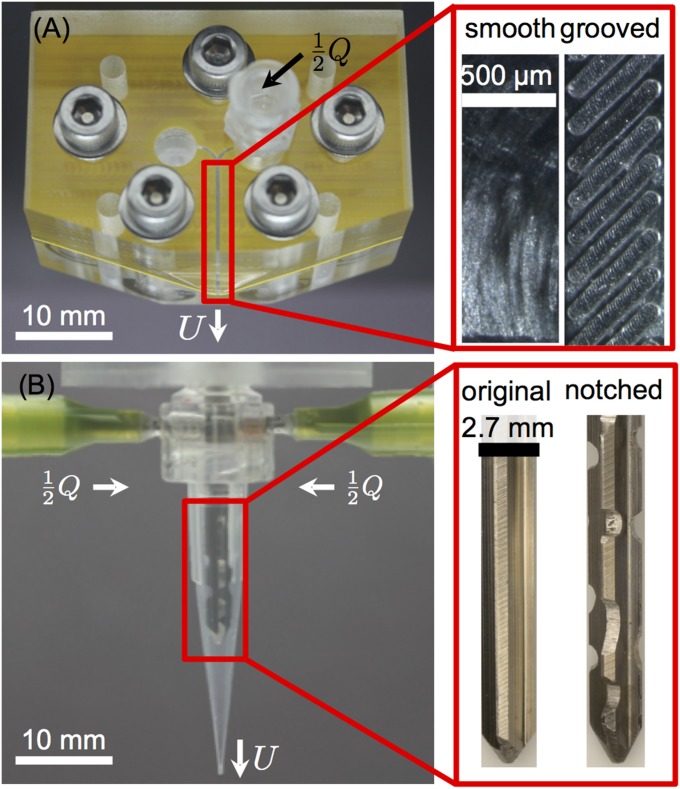

The passive mixers are machined from two poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) polymer blocks using a CNC-mill (8540, Sherline Products Inc.). The grooves are milled with a 200-µm end mill (Ultra-Tool International), whereas all larger features are milled with a 3-mm end mill. Luer lock connectors are added to each block. A 480-µm-thick plastic (PETG) shim stock (Artus Corp.) is machined and used as a spacer between the two PMMA blocks, which are bolted together to ensure a tight seal. An optical image of one of the passive mixers used in this study is shown in Fig. S6 along with expanded views of the walls of the passive mixer. For both designs, the channel dimensions are mm and µm. In the grooved-wall mixer, the spacing between 120-µm-wide grooves positioned 45° relative to the primary direction of flow is µm. The net volume of the mixing chamber is 3.6 µL, and thus the mixer can be purged (to change extrudate composition) in ∼15 mm of printed material.

Fig. S6.

Optical images of the mixers. (A) The passive mixer consists of a Y-type junction and a long duct of hydraulic diameter µm and length mm. The channel surfaces of the passive mixers are shown in the magnified image. (B) The active mixer consists of two inlet channels connecting to the central mixing volume of length mm, diameter mm, and outlet diameter µm with the impeller of diameter mm. The two types of impellers are shown in the magnified image. An alternative design with metal fixtures is implemented for mixing with highly viscous epoxy systems.

The concentration distributions of the dye in the passive mixers are shown by the color images of the nozzle cross-section in Fig. S2 on a phase space spanned by the Bingham and Péclet numbers. Measurements of Newtonian fluids lie on the abscissa (Bi = 0). For water, , indicating that inertially driven secondary flows may affect the mixing at the highest flow rates. However, for all other fluids , so inertial instabilities are negligible.

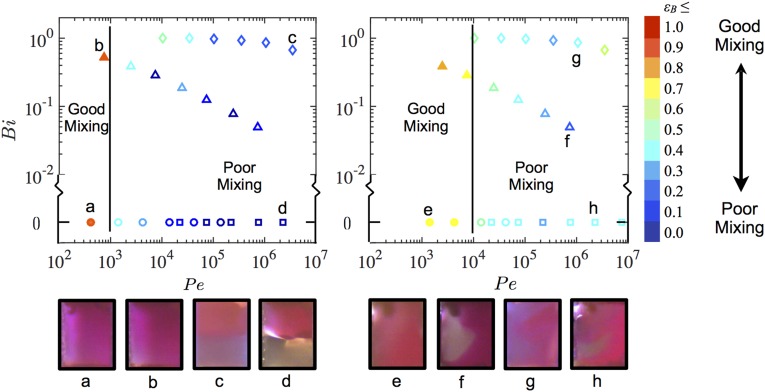

Fig. S2.

Mixing in the passive mixer. Plot of mixing efficiency in the phase space for the (A) SWPMs and (B) GWPMs as determined from the color saturation images of the nozzle cross-sections for water (circle), water:glycerol [20:80 wt %] (square), lubricant gel (upright triangle), and Pluronic (diamond). Solid and hollow symbols indicate regimes of good and poor mixing, respectively, corresponding to images in which a sharp interface between dyed and undyed streams could be visually observed. Representative grayscale images of the color saturation are shown below each plot with bright and dark regions indicating dyed and undyed streams. The color of the border indicates the test fluid: (A, a and e, water; A, b and f, lubricant gel; B, c and g, Pluronic; B, d and h, water:glycerol [20:80 wt %].

The mixing efficiency for the smooth-wall passive mixer (SWPM), in which mixing occurred due to molecular diffusion alone, is plotted in Fig. S2A. Consequently, is the definitive parameter governing mixing efficiency, which is relatively independent of . Referring to Eq. 1, the transition from the regime of good mixing (solid symbols, Fig. S2 A, a and b) to poor mixing (hollow symbols, Fig. S2 A, c and d) is expected at flow rates corresponding to a critical Péclet number of order for this mixer, which is apparent for all fluids. Poor mixing conditions correspond to images in which a sharp interface between dyed and undyed streams can be visually observed. The absolute -value of this delineator is arbitrary, but its use is intended to convey clearly the inability of the SWPM to achieve mixing at higher flow rates.

The plot of from the grooved-wall passive mixer (GWPM) is shown in Fig. S2B. The grooves clearly affect the qualitative features of the dye homogenization for Newtonian fluids (Fig. S2 B, h). For the non-Newtonian inks, the grooves have less of an effect on the advective motion in the unyielded inner core of the fluid, particularly for (Fig. S2 B, g), resulting in relatively unmixed streams. For , the interface is still distinct, however it is typically warped from its initial horizontal orientation due to cross-stream motion in the yielded material near the walls (Fig. S2 B, f). Also, at all values of , the values of in the GWPM are higher than the corresponding value for the SWPM, generally indicating better mixing in the GWPM for the same flow rate. Furthermore, the boundary between good (Fig. S2 B, e) and poor (Fig. S2 B, f–h) mixing is moved to a higher transition . At flow rates higher than this threshold, the -values decrease, indicating poorer mixing.

Although more optimal groove shape and spacing can be incorporated into the GWPM, paradoxically, for a passive mixer to homogenize yield stress materials, low (low , sufficient mixing time) and (high , sufficient fluidization) are required. Changes to the channel dimensions to satisfy this constraint, however, are likely to come at the cost of increased pressure drop across the mixer. For the flow of a Newtonian fluid through a mixer, which is analogous to flow through an annulus (41) of inner diameter and outer diameter , the channel dimensions, flow rate, and pressure are related by

| [S1] |

where , is the pressure drop, is the fluid viscosity, and (for the passive mixers ). Accordingly, for a maximum operating pressure drop and target flow rate, the aspect ratio of the mixer must be reduced to increase the maximum attainable . This result is exactly counter to the constraints on the aspect ratio of the passive mixer to attain good mixing at increasing according to Eqs. 1 and 2. These results have been summarized in Fig. S1. Hence these fundamental constraints on the pressure drop and operating values of and for a large range of ink materials can only be overcome by an active mixing system.

Mixing Newtonian Fluids

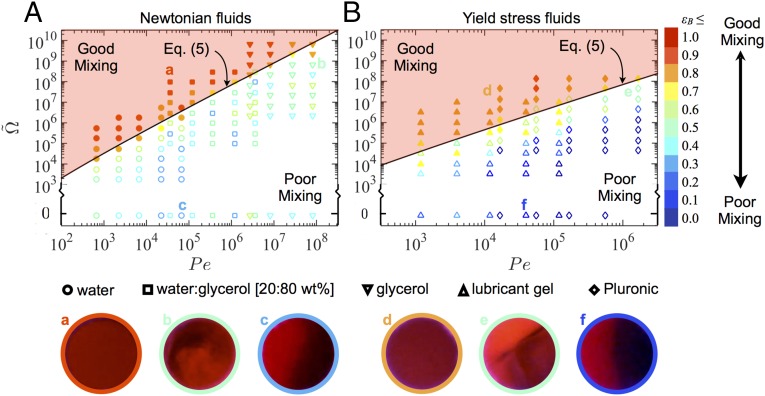

The ability of the modeling framework given by Eq. 4 to capture the mixing of Brownian particles over more than five orders of Péclet number is clearly demonstrated in Fig. 3A using three different Newtonian fluids (water µ = 0.001 Pa·s, 20:80 wt % water:glycerol µ = 0.054 Pa·s, and glycerol µ = 1.2 Pa·s, Table S1). A dyed and undyed stream of the same fluid are mixed at equal flow rates [i.e., ], and the concentration distribution in the cross-section of the nozzle outlet is imaged. The extent of mixing for Brownian particles is quantified by index , where is the coefficient of variation of the image intensity ( with increasing homogenization), which has been previously used in mixing studies in microchannels (10, 13, 31), and is the maximum coefficient of variation for the unmixed fluid.

Fig. 3.

Active mixing of Brownian species in the microfluidic mixer. Plot of mixing efficiency in the phase space for (A) Newtonian liquids and (B) yield stress fluids as determined from the red channel intensity of images of the nozzle cross-sections. The solid black curves follow the relation , which separates the regions of good and poor mixing indicated by solid and hollow symbols respectively, corresponding to images in which a sharp interface between dyed and undyed streams could be visually observed. Representative images of the nozzle cross-section (400-µm diameter) are shown below each plot with bright and dark regions indicating dyed and undyed streams: A, a, water:glycerol [20:80 wt %]; A, b, glycerol; A, c, water; B, d and f, lubricant gel; B, e, Pluronic.

Table S1.

Material and rheological properties of fluids studied in the mixing nozzles at 22 °C

| Fluid | η, Pa·s | ρ, kg/m3 | , µm2/s | τy, Pa | K, Pa·sb | b |

| Water | 0.001 | 1,000 | 500 | |||

| Water:glycerol [20:80 wt %] | 0.054 | 1,200 | 9.3 | |||

| Glycerol | 1.2 | 1,250 | 0.41 | |||

| Lubricant gel | 1,000 | 280 | 20 | 20 | 0.44 | |

| Pluronic F127 | 1,050 | 20 | 500 | 2 | 0.85 | |

| SE 1700 | 1,400 | 180 | 0.65 |

Whereas mixing in the passive mixer is governed solely by (Fig. S2), the mixing process in the active chaotic mixer can be controlled by varying the dimensionless impeller speed according to the rewritten form of Eq. 4:

| [5] |

Hence, for a constant value of , the mixing efficiency in the active mixer is controlled by two independent parameters (,), which can be systematically varied to generate the plot of -values in the phase space shown in Fig. 3A. Representative images of the nozzle cross-section for good (Fig. 3 A, a) and poor (Fig. 3 A, c) mixing are also shown. The boundary between these two regimes is delineated by the black curve given by , which lies approximately along the -isocontour at which a distinct interface between dyed and undyed streams could not be easily identified (Fig. 3 A, b). The precise value of the proportionality coefficient (taken as unity here) is empirically determined for the particular active mixer used and is not expected to be universal for all active mixing systems. Additionally, fluid inertial effects may affect the mixing in water because , but those are negligible for all other fluids investigated because . Nevertheless, this result clearly validates the applicability of the derivation of Eqs. 4 and 5 for active mixing of Newtonian liquids.

Mixing Yield Stress Fluids

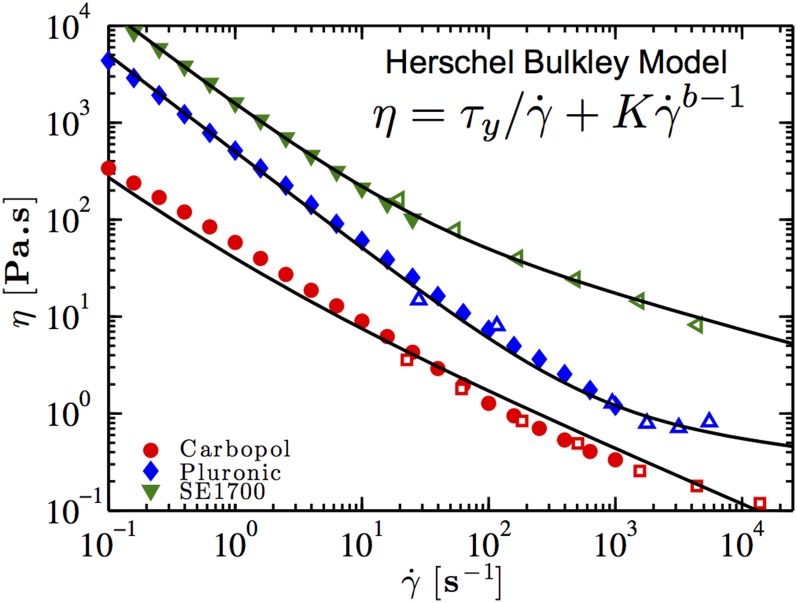

The rheological behavior of a yield stress material is described by the Herschel–Bulkley (HB) model (32), , with yield stress , consistency index , and power-law exponent (Table S1 and Fig. S3). At low Reynolds number , with density , velocity , and viscosity given by (Newtonian fluid) or the HB model (yield stress fluid) evaluated at a characteristic shear rate through the nozzle , the relative importance of the yield stress is given by the Bingham number . For a passive mixer . At low shear rates () the majority of the material moves through the nozzle as a solid plug, inhibiting convective mixing. At higher shear rates () viscous stresses fluidize the material, facilitating mixing caused by chaotic motion. Accordingly, passive mixing of yield stress materials is restricted by two competing constraints: low (low , sufficient mixing time), but (high , sufficient fluidization). Conversely, in the active mixer, the rapid motion of the impeller induces a shear rate in the gap, and thus the extent of fluidization, given by the value of can be controlled independently from the flow rate, thereby enabling efficient mixing of yield stress materials.

Fig. S3.

Rheological flow curves of the three non-Newtonian ink formulations used in calibration tests in this work at 22 °C. Data taken with the rotational rheometer (filled symbols) and the capillary rheometer (hollow symbols) are shown. The black solid lines are the respective fits of the HB model given by the fitting parameters listed in Table S1.

To determine the effectiveness of active mixing, two yield stress materials, a carbopol lubricant gel and an aqueous surfactant solution of Pluronic F-127 (Table S1), are studied (Fig. 3B). These fluids cannot be homogenized via passive mixing (Fig. S2) over reasonable distances (<15 mm) or timescales (0.5–30 s). However, the fluids can be efficiently mixed using the active mixer, for which the transition from uniform (Fig. 3 B, d) to poor (Fig. 3 B, f) mixing occurs at the boundary (Fig. 3 B, e) also spanned by . The value of for the lubricant gel ranges between and for Pluronic , hence at the highest rotation rates these materials are thoroughly fluidized. The similarity in the location of the boundary between mixing regimes for both the Newtonian (Fig. 3A) and yield stress (Fig. 3B) fluids also suggests that the materials are sufficiently fluidized so that the precise value of does not strongly affect the mixing efficiency of the active mixer, and the scaling relationship in Eq. 4 can be successfully applied to a wide range of fluids.

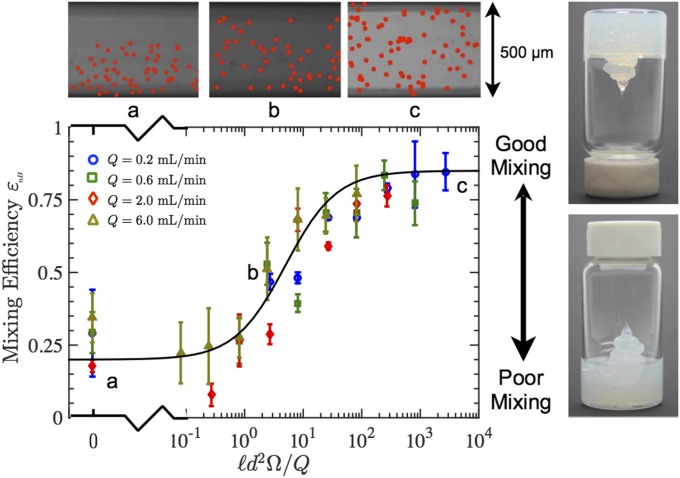

The active mixer can also mix liquids that contain large fillers, such as pigments or fibers (24), for which thermal motion is negligible (Methods). Because these species cannot diffusively mix, uniform homogenization occurs only if the final length scale of interdigitation between the incoming streams approaches that of the particle size . Following similar reasoning used to derive Eq. 4, the ratio of the impeller speed to flow rate must be

| [6] |

When mixing large fillers (i.e., non-Brownian particles), the minimum impeller speed scales linearly with flow rate, or equivalently a minimum critical number of impeller revolutions within the residence time of the mixer is required for efficient mixing.

To further demonstrate active mixing, two streams of silicone-based inks are homogenized, one that is particle-free and the other laden with = 6-µm fluorescent polystyrene particles. Representative optical images of the particles in poorly-, moderately-, and well-mixed filaments are shown in Fig. 4. The concentration is selected to ensure nearly all particles within the filament are clearly visible. To quantify mixing efficiency, the Shannon entropy index (33) of the particle distributions across the filament width is measured under fluorescence microscopy to calculate the normalized mixing index for non-Brownian particles defined by

| [7] |

The entropy of a hypothetically perfectly mixed filament is , and the entropy of a completely unmixed filament is , for which particles are present in only half the filament width (Methods). The entropy index (Fig. 4) follows a sigmoidal profile with mixing ratio between the limits of poor and good mixing, as illustrated by the black curve, which has been added to guide the eye. Above a critical value of the mixing ratio , reaches a plateau indicating uniform particle dispersion in the filament. This result is in agreement with the proposed scaling relationship in Eq. 6, indicating that the threshold for thorough mixing is given by , or ∼16 revolutions per residence time are required.

Fig. 4.

Semilog plot of mixing efficiency of large filler particles in a polydimethylsiloxane ink as a function of mixing ratio for four different flow rates. The solid black curve is added only to guide the eye. Three example particle distributions in the printed filament corresponding to different mixing ratios are shown. The red dots have been added to indicate the position of each tracer particle in the filament. The failure of to attain precisely its expected asymptotic values of zero (perfectly unmixed) and one (perfectly mixed) at, respectively, low and high dimensionless rotation speeds may arise from the low particle density in the filament, which may prevent statistical convergence. The yield stress behavior of this ink is clearly illustrated by its shape retention when inverted in a vial.

Active Mixing Printheads for Multimaterial 3D Printing

With this mixing capability in hand, we created a microfluidic printhead that enables 3D printing of multimaterial architectures via on-the-fly active mixing of concentrated viscoelastic inks. The ability to locally vary the composition and properties of 3D printed structures would open new avenues to creating flexible electronics, sensors, soft robots (34), structural composites (24), and vascularized tissue constructs with controlled chemical gradients (25, 35, 36). As a first demonstration, we printed a silicone-based elastomeric ink in which the concentration of a fluorescent pigment is continuously and discretely changed during printing (Fig. 5A). A continuously varying compositional gradient is created, as denoted visually via a color gradient, by printing a given amount of material at five different monotonically varying flow rate ratios of clear and fluorescent ink without any purging step (Fig. 5A, Top). Conversely, discrete changes in fluorescence are achieved by purging the nozzle after changing to a new flow rate ratio. This latter approach is used to produce the structures in Fig. 5A (Bottom), for which the material transitions incrementally from brightly fluorescent to clear in eight sequentially decreasing ratios of fluorescent to clear ink as printing progresses. The color uniformity in all eight segments clearly demonstrates that the impeller-based active mixing printheads are capable of homogenizing these model viscoelastic inks.

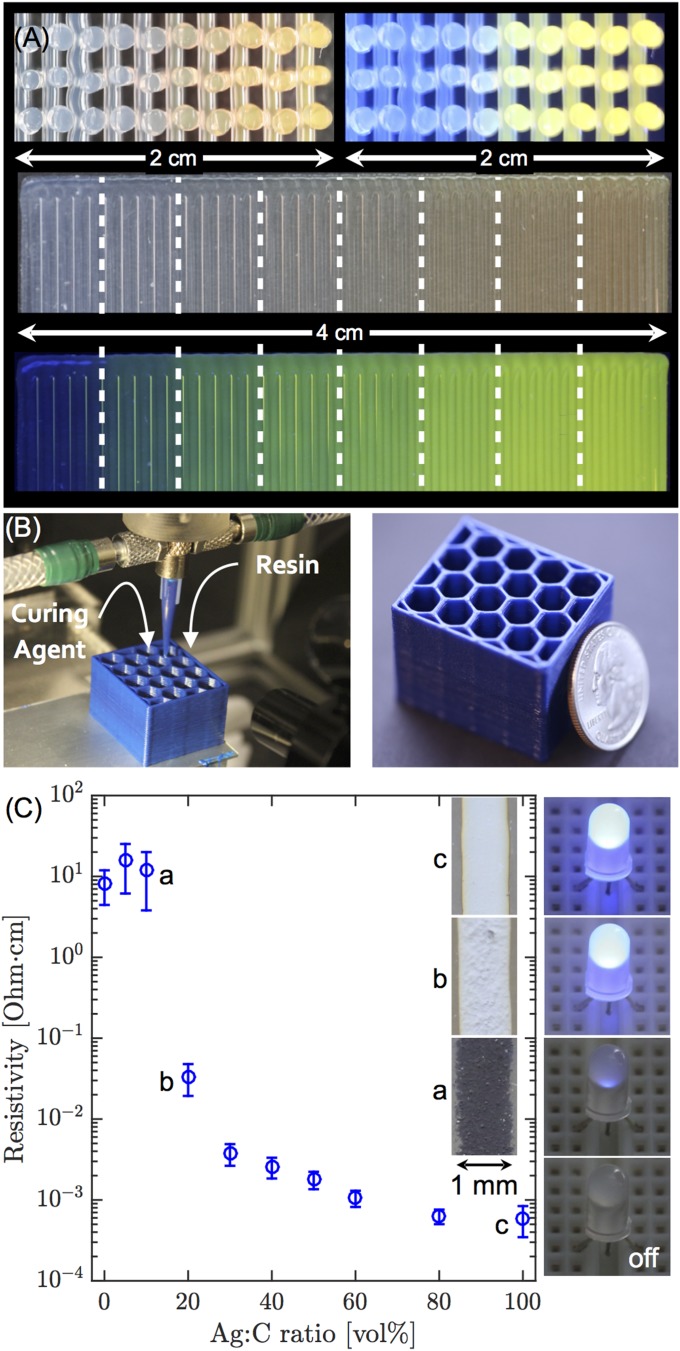

Fig. 5.

(A, Top) Images of the cross-section of a 3D rectangular lattice structure of SE 1700 showing continuous change in fluorescent pigment concentration under bright light (Left) and UV radiation (Right). (A, Bottom) Images of a 2D carpet structure showing a discretely varying fluorescent gradient at eight different mixing ratios under bright light (Top) and UV radiation (Bottom). Dashed white lines have been added to mark the regions of different mixing ratios. (B) Three-dimensional printing of a two-part epoxy honeycomb structure. A coin is shown to indicate scale. (C) Plot of resistivity of colloidal nanoparticle silver and carbon inks at varying volume ratios mixed in the active mixer. (Inset) Images showing the illumination intensity of a blue LED connected in series to selected ink traces with a constant applied voltage (2.55 V). Sections of the corresponding traces are shown at the side of each LED.

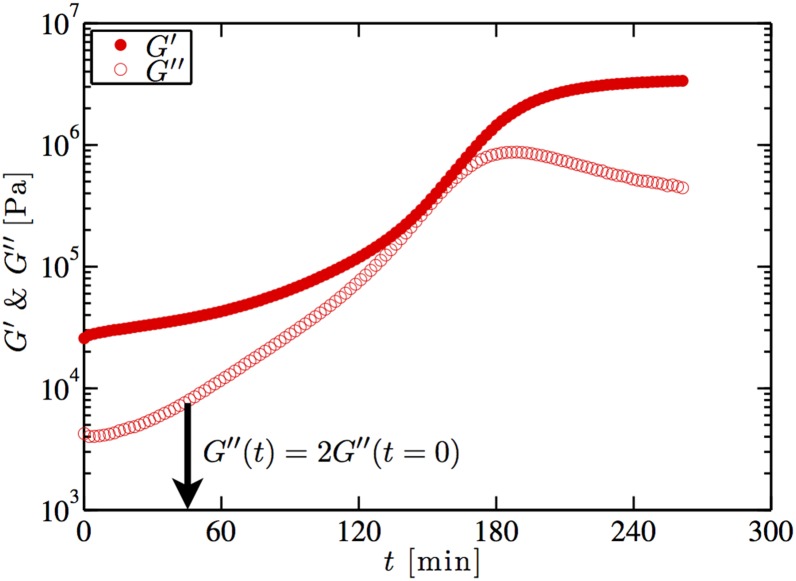

As a second demonstration, we printed chemically reactive materials that are typically challenging to pattern due to their rapid changes in rheological properties over time. By using an active mixing printhead, we can overcome such kinetic constraints, provided the timescale of mixing is much faster than the characteristic reaction time of the ink. For example, a two-part epoxy (20:80 vol % curing agent:resin with a pot-life of 45 min, Fig. S4) is used to print the 3D honeycomb structure (24) shown in Fig. 5B. Under the printing conditions used, the residence time within the active mixing nozzle is 30 s, which ensures their patterning over far longer periods than their pot-life, if necessary. Furthermore, this mixer design reduces the amount of wasted material by requiring only the volume of material necessary for the structure to be mixed (i.e., the mixer volume).

Fig. S4.

Evolution of the storage and loss moduli with time after mixing at 22 °C, as measured using a 25-mm plate–plate geometry on an AR2000ex (TA Instruments) at frequency rad/s and strain amplitude . The measured pot-life of the epoxy is 45 min, which is the point at which the loss modulus is double its initial value as indicated by the arrow.

As a final demonstration, we use the mixing printhead to tailor the functionality of the 3D printed structures on-the-fly. For example, the electrical resistivity of a printed structure is continuously controlled over nearly five orders of magnitude (Fig. 5C) by varying the ratio of two streams of highly conductive silver nanoparticle (37, 38) (bulk resistivity ohm⋅cm) and carbon colloidal inks (bulk resistivity ohm⋅cm). The printed traces are integrated into an electrical circuit to which a constant voltage (2.55 V) is applied and the resultant illumination intensity of a light-emitting diode (LED) connected in series with a trace is observed to visualize the electrical resistance of each mixing ratio. The ability to dynamically control the electrical resistance of a printed feature opens new opportunities for embedding electrical circuitry within 3D printed objects.

Conclusion

We have described a rational framework for designing microfluidic active mixers using a rotating impeller that is consistent with past scaling analyses for passive mixers. We have also demonstrated mixing of a wide range of yield stress fluids in active microfluidic mixers with a gap size on the order of hundreds of micrometers. The key attribute of this active mixing approach is to decouple the mixing intensity from the flow rate and the volume of the mixer. Although we have specifically highlighted its utility for multimaterial 3D printing, our design and operating criteria for active microfluidic mixers should be broadly applicable for mixing complex fluids at the microscale.

Methods

Fluid Preparation.

The water:glycerol [20:80 wt %] mixture is prepared from deionized water and glycerol (Macron). The aqueous polymer lubricant (Klein Tools) is obtained commercially, and the Pluronic solution is prepared by dissolving 30 wt % Pluronic F-127 (Sigma-Aldrich) in deionized water at 4 °C for 48 h. A red molecular tracer dye (IFWB-C7, Risk Reactor) is added to each fluid at 1 µL/g. To measure the mixing of non-Brownian particles, 6-µm polystyrene tracer particles (Fluoro-Max, Thermo Scientific) at 0.04 wt % are added to polydimethylsiloxane (SE 1700, Dow Corning).

To demonstrate 3D printing with variable color, a stream of clear and fluorescent (3-µL/g DFSB-C175 orange, Risk Reactor) 10:1 resin:curing agent SE 1700 are mixed. The resin of the two-part epoxy used to print honeycomb structures is composed of 87 wt % EPON 828 (Momentive), 9 wt% TS-720 fumed silica (Cabot), 4 wt% blue epoxy pigment (System 3). The curing agent is composed of 90 wt% Epikure 3234 (Momentive) 10 wt % TS-720 fumed silica (Cabot).

The preparation of the silver ink is described elsewhere (37). The carbon ink is prepared from conductive carbon black powder (Cabot Mogul-L), which is dispersed in water (1 wt %) via sonication and sodium hydroxide is added to attain pH = 9. This dispersion is gradually added to a 3 wt % aqueous hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC) solution, which is homogenized by a planetary mixer (Thinky) and partially dried under vacuum. The process is sequentially performed to reach a 2:1 HEC:carbon ratio by weight. Each trace is printed onto an electrically insulated substrate, and the resistance of 10 mm × 1 mm × 10 µm sections is measured using a four-point probe.

Fluid Rheology.

The viscosity of each test fluid is measured with a rotational rheometer (AR2000ex, TA Instruments) at 22 °C. At shear rates above , material is ejected from the gap due to edge fracture (39) preventing reliable measurements at higher shear rates. Alternatively, a custom capillary rheometer is used to measure the viscosity at shear rates . This system consists of a syringe pump (PHD Ultra, Harvard Apparatus), 1.0-mL glass Luer lock syringe (Hamilton Gastight), a diaphragm pressure transducer (PX44E0-1KGI, Omega Engineering), and disposable Luer lock needle tips (Norsdon EFD). The pressure drop across the capillary tips is measured over a range of flow rates. The Bagely correction (40) and the Weissenberg–Rabinowitsch correction (40) are applied to determine the resultant flow curves shown in Fig. S3.

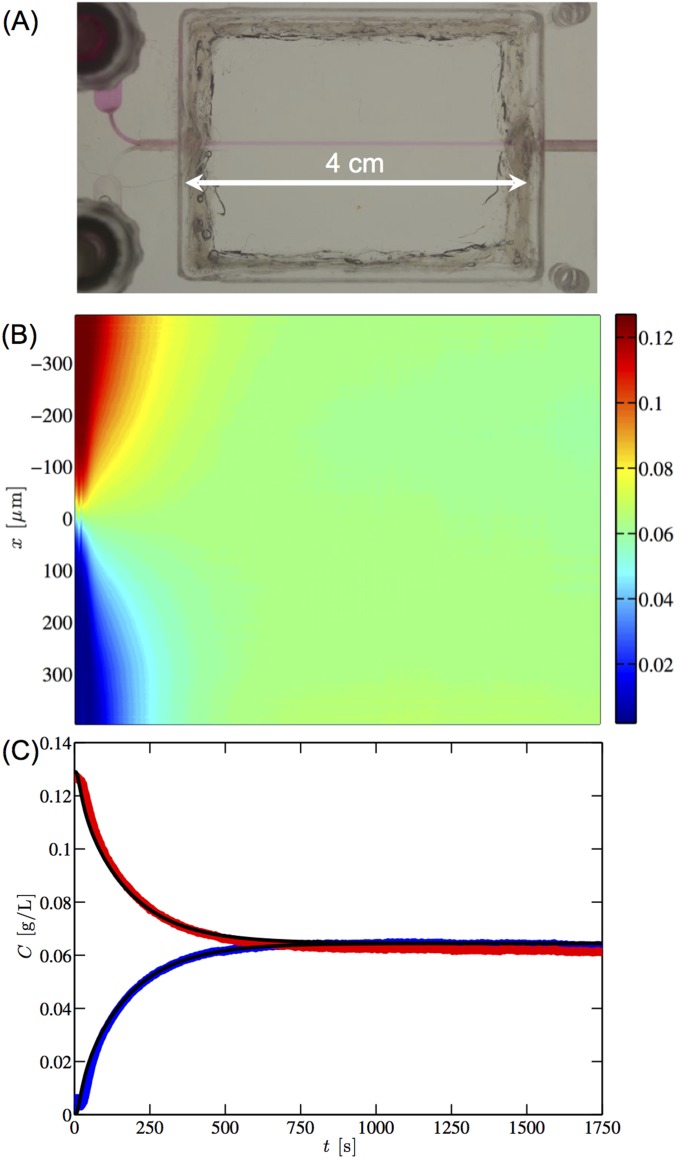

Measurement of Diffusion Coefficients.

The molecular diffusion coefficient of the IFWB-C7 dye (rhodamine-WT, absorption/emission: 550/588 nm, Risk Reactor) is measured in the aqueous solutions using a custom Y-type rectilinear capillary channel with inner dimensions µm (Vitrocom). The channel is submerged in immersion oil (, type FF, Cargille) to minimize refraction, illuminated with a mercury lamp (local emission peak at 546 nm) and visualized through a tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC) filter cube (peak transmittance 580–630 nm) using a QColor 5 camera (Olympus) and a 10× objective on an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Olympus IX71). Calibration measurements are taken to relate dye concentration to emitted light intensity at each pixel to account for spatial variations in the illumination intensity. In each measurement, the dyed and undyed fluids are pumped at equal flow rates into the channel. Once a sharp interface between the two streams stabilizes at the channel midplane, the pumping is stopped and the subsequent evolution of the concentration profile across the channel width is recorded at 1 cm downstream from the Y junction.

The evolution equation for the concentration across the channel is

| [8] |

where x is the spatial coordinate, t is time, and is the molecular diffusion coefficient. The initial condition for the experiments in the capillary channel is , where is the initial concentration in the first stream and is the Heaviside function. There are no flux boundary conditions at both walls, at . The concentration profile is given by

| [9] |

The value of is determined from the average of multiple fits of Eq. 10 to the measured concentration profiles at multiple positions along the channel width (). An example concentration profile is shown in Fig. S5.

Fig. S5.

Measurements of the diffusion coefficient of the IFWB-C7 dye (rhodamine-WT, Risk Reactor) at 23 °C. (A) Top view of the capillary with the injected dyed and undyed streams. (B) Spatiotemporal plot of experimentally measured dye concentration [g/L] in water (viscosity Pa·s). (C) Evolution of the concentration at µm (red) and µm (blue). The black curves are the fit of from Eq. 9 with µm, µm, g/L, and µm2/s. The Stokes–Einstein equation is used to estimate the molecular diameter of the tracer dye nm.

For this study, a particle is considered Brownian if the ratio of thermal stresses acting on a particle to viscous stresses in the Newtonian fluids or the yield stress of the ink (, and , respectively) far exceeds unity, where is the Boltzmann constant, is the absolute temperature, is the fluid viscosity, is the particle diameter, and is the yield stress. Measurements of the dye diffusion coefficient (Fig. S5) indicate that its molecular diameter is approximately nm. For K, Pa·s (glycerol), m/s (maximum print speed), and Pa (Pluronic), the ratios and , which confirm the dominance of thermal forces on the dye molecules. Conversely, for the -µm fluorescent particles, and hence the particles are non-Brownian.

Nozzle Manufacture.

The active mixer is fabricated by gluing two 1.54-mm-diameter (gauge 14, Nordsen EFD) needle tips into a threaded plastic male Luer lock connector. The connector is attached to a poly(methyl methacrylate) block mounted to the nozzle superstructure. The impeller is made from a -mm-diameter reamer (Alvord-Polk Tools) that is ground down to fit within the nozzle volume. Notches are added to one of the impellers to enhance mixing. A stepper motor drives the impeller shaft, which is sealed using an O-ring. A second active mixer using metal Luer lock components is fabricated to tolerate the higher pressures necessary for the two-part epoxy. The overall dimensions of this mixing nozzle are mm and mm. The mixer volume with the disposable nozzle tip is ∼150 µL. Hence for a nozzle with tip diameter µm, at least 760 mm of printed material is required to purge the mixer.

Flow Visualization, Imaging, and Mixing Quantification.

To image the concentration distribution of the fluorescent tracer dye in the nozzle cross-section, the test fluids are extruded onto a transparent Petri dish under which a uEye camera (Imaging Development Systems) is positioned. Flow rates range from mL/min. The rotational speeds of the impeller are in the range rad/s ( rpm). For all calibration experiments, the impeller shaft with grooves but no notches (Fig. S6) is used, because the notched impeller induces sufficient cross-streamwise fluid motion, even for no rotation (i.e., ), so as to make identification of the poor mixing regime inordinately challenging. Image analysis of the concentration profile was done in MATLAB. The mean and SD of the color saturation level (passive mixer) of the red channel intensity (active mixer) in the image are calculated to determine the coefficient of variation , and thereby the mixing index .

The distributions of non-Brownian fluorescent particles in the printed SE 1700 filaments are measured with a 10× objective on an inverted epifluorescence microscope (Olympus IX71) using a QColor 5 camera (Olympus). A MATLAB script written by the authors is used to determine the Shannon entropy index (33) of the particles , where is the probability of finding a particle in the jth bin for the probability density function with bins. Each bin corresponds to 20-µm sections of the printed filament. Referring to Eq. 7, the measured entropy of the printed filament is . The entropy of a hypothetically perfectly mixed filament is , for which particles are uniformly distributed, hence . The entropy of a completely unmixed filament is , for which particles are uniformly present in only half the filament width, so for and for .

Printing and Mixing Control.

The nozzle is fixed in the laboratory frame and held by a superstructure and substrate motion is controlled by a high-precision XYZ gantry (Aerotech, Inc.). The inks are contained in 3-, 5-, or 10-mL plastic syringes (Becton Dickinson) and driven by two opposed syringe pumps (PHD Ultra, Harvard Apparatus) that are controlled directly by the NView HMI software (Aerotech, Inc.).

In calibration tests, the streams are mixed in equal portion, but for the example applications, homogenization is required at ratios as large as 9:1, whose effect on mixing quality has not been thoroughly characterized. Hence, to ensure full mixing according to Eq. 6, low flow rates ( mL/min) and nearly the maximum achievable impeller speed ( rad/s, 240 rpm) are selected to ensure a large mixing ratio . Furthermore, multiple notches are added along the length of the impeller (Fig. S6) to add rotational asymmetry to the impeller and thereby enhance mixing (15).

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Bell, T. Busbee, A. Kotikian, and A. Russo for experimental assistance, and M. Scott and J. Muth for valuable discussions. This work was supported by the Department of Energy Energy Frontier Research Center on Light-Material Interactions in Energy Conversion under Grant DE-SC0001293. T.J.O. acknowledges support from the Intelligence Community Postdoctoral Fellowship program. D.F. acknowledges support from the Society in Science Branco-Weiss Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1509224112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nguyen N-T, Wu Z. Micromixers—a review. J Micromech Microeng. 2005;15(2):R1–R16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hessel V, Löwe H, Schönfeld F. Micromixers—a review on passive and active mixing principles. Chem Eng Sci. 2005;60(8):2479–2501. [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Ali J, Sorger PK, Jensen KF. Cells on chips. Nature. 2006;442(7101):403–411. doi: 10.1038/nature05063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stott SL, et al. Isolation of circulating tumor cells using a microvortex-generating herringbone-chip. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(43):18392–18397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012539107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haswell SJ, Watts P. Green chemistry: Synthesis in micro reactors. Green Chem. 2003;5:240–249. doi: 10.2174/1386207043328526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenis PJ, Ismagilov RF, Whitesides GM. Microfabrication inside capillaries using multiphase laminar flow patterning. Science. 1999;285(5424):83–85. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stone HA, Stroock AD, Ajdari A. Engineering flows in small devices. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 2004;36:381–411. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ottino JM, Wiggins S. Introduction: Mixing in microfluidics. Philos Trans R Soc London, Ser A. 2004;362(1818):923–935. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2003.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Squires T, Quake S. Microfluidics: Fluid physics at the nanoliter scale. Rev Mod Phys. 2005;77(3):977–1026. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stroock AD, et al. Chaotic mixer for microchannels. Science. 2002;295(5555):647–651. doi: 10.1126/science.1066238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schönfeld F, Hardt FS. Simulation of helical flows in microchannels. AIChE J. 2004;50(4):771–778. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Therriault D, White SR, Lewis JA. Chaotic mixing in three-dimensional microvascular networks fabricated by direct-write assembly. Nat Mater. 2003;2(4):265–271. doi: 10.1038/nmat863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deseigne J, Cottin-Bizonne C, Stroock AD, Bocquet L, Ybert C. How a “pinch of salt” can tune chaotic mixing of colloidal suspensions. Soft Matter. 2014;10(27):4795–4799. doi: 10.1039/c4sm00455h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groisman A, Steinberg V. Efficient mixing at low Reynolds numbers using polymer additives. Nature. 2001;410(6831):905–908. doi: 10.1038/35073524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arratia PE, Kukura J, Lacombe J, Muzzio FJ. Mixing of shear-thinning fluids with yield stress in stirred tanks. AIChE J. 2006;52(7):2310–2322. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wendell DM, Pigeonneau F, Gouillart E, Jop P. Intermittent flow in yield-stress fluids slows down chaotic mixing. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2013;88(2):023024. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.88.023024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morissette SL, Lewis JA, Cesarano JI, Dimos DB, Baer T. Solid freeform fabrication of aqueous alumina–poly(vinyl alcohol) gelcasting suspensions. J Am Ceram Soc. 2000;83(10):2409–2416. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipson H, Kurman M. Fabricated: The New World of 3D Printing. John Wiley & Sons; Indianapolis: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis JA. Direct ink writing of 3D functional materials. Adv Funct Mater. 2006;16(17):2193–2204. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smay JE, Cesarano J, Lewis JA. Colloidal inks for directed assembly of 3-D periodic structures. Langmuir. 2002;18(14):5429–5437. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun K, et al. 3D printing of interdigitated Li-ion microbattery architectures. Adv Mater. 2013;25(33):4539–4543. doi: 10.1002/adma.201301036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gratson GM, Xu M, Lewis JA. Microperiodic structures: Direct writing of three-dimensional webs. Nature. 2004;428(6981):386. doi: 10.1038/428386a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahn BY, et al. Omnidirectional printing of flexible, stretchable, and spanning silver microelectrodes. Science. 2009;323(5921):1590–1593. doi: 10.1126/science.1168375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Compton BG, Lewis JA. 3D-printing of lightweight cellular composites. Adv Mater. 2014;26(34):5930–5935. doi: 10.1002/adma.201401804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolesky DB, et al. 3D bioprinting of vascularized, heterogeneous cell-laden tissue constructs. Adv Mater. 2014;26(19):3124–3130. doi: 10.1002/adma.201305506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chertkov M, Lebedev V. Boundary effects on chaotic advection-diffusion chemical reactions. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;90(13):134501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.134501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burghelea T, Segre E, Steinberg V. Mixing by polymers: Experimental test of decay regime of mixing. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;92(16):164501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.164501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lebedev VV, Turitsyn KS. Passive scalar evolution in peripheral regions. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2004;69(3):036301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.69.036301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sundararajan P, Stroock AD. Transport phenomena in chaotic laminar flows. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2012;3:473–496. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-062011-081000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mensing GA, Pearce TM, Graham MD, Beebe DJ. An externally driven magnetic microstirrer. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2004;362(1818):1059–1068. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2003.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stroock AD, McGraw GJ. Investigation of the staggered herringbone mixer with a simple analytical model. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2004;362(1818):971–986. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2003.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bird RB, Armstrong RC, Hassager O. Dynamics of Polymer Liquids. 2nd Ed. Vol 1 John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han H, Furst EM, Kim C. Lagrangian analysis of consecutive images: Quantification of mixing processes in drops moving in a microchannel. Rheol Acta. 2014;53(7):489–499. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ilievski F, Mazzeo AD, Shepherd RF, Chen X, Whitesides GM. Soft robotics for chemists. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50(8):1890–1895. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosoff WJ, McAllister R, Esrick MA, Goodhill GJ, Urbach JS. Generating controlled molecular gradients in 3D gels. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;91(6):754–759. doi: 10.1002/bit.20564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ashe HL, Briscoe J. The interpretation of morphogen gradients. Development. 2006;133(3):385–394. doi: 10.1242/dev.02238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russo A, et al. Pen-on-paper flexible electronics. Adv Mater. 2011;23(30):3426–3430. doi: 10.1002/adma.201101328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker SB, Lewis JA. Reactive silver inks for patterning high-conductivity features at mild temperatures. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(3):1419–1421. doi: 10.1021/ja209267c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanner RI, Keentok M. Shear fracture in cone-plate rheometry. J Rheol. 1983;27(1):47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macosko CW. Rheology Principles, Measurements and Applications. Wiley-VCH; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 41.White FM. Viscous Fluid Flow. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]