Significance

Mammalian Y chromosomes are believed to evolve mainly through gene inactivation and loss. Drosophila Y chromosomes seem to not obey this rule, as gene gains are the dominating force in their evolution. Here we describe flagrante delicto Y (FDY), a very young gene that shows how Y-linked genes were acquired. FDY originated 2 million years ago from a duplication of a contiguous autosomal segment of 11 kb containing five genes that inserted into the Y chromosome. Four of these autosome-to-Y gene copies became inactivated (“pseudogenes”), lost part of their sequences, and most likely will disappear in the next few million years. FDY, originally a female-biased gene, acquired testis expression and remained functional.

Keywords: Y chromosome, Drosophila melanogaster, PacBio, FDY, vig2

Abstract

Contrary to the pattern seen in mammalian sex chromosomes, where most Y-linked genes have X-linked homologs, the Drosophila X and Y chromosomes appear to be unrelated. Most of the Y-linked genes have autosomal paralogs, so autosome-to-Y transposition must be the main source of Drosophila Y-linked genes. Here we show how these genes were acquired. We found a previously unidentified gene (flagrante delicto Y, FDY) that originated from a recent duplication of the autosomal gene vig2 to the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. Four contiguous genes were duplicated along with vig2, but they became pseudogenes through the accumulation of deletions and transposable element insertions, whereas FDY remained functional, acquired testis-specific expression, and now accounts for ∼20% of the vig2-like mRNA in testis. FDY is absent in the closest relatives of D. melanogaster, and DNA sequence divergence indicates that the duplication to the Y chromosome occurred ∼2 million years ago. Thus, FDY provides a snapshot of the early stages of the establishment of a Y-linked gene and demonstrates how the Drosophila Y has been accumulating autosomal genes.

The mammalian Y chromosome has the lowest gene density of any chromosome, and most of its genes have a homolog on the X. This pattern is consistent with the mammalian sex chromosomes having originated from an ordinary pair of chromosomes, followed by massive gene loss from the Y (1–4). In contrast, the closest homologs of all Drosophila melanogaster Y-linked protein-encoding genes are autosomal, strongly suggesting that its Y chromosome has been acquiring genes from the autosomes (5–7). Indeed, gene gains, and not gene losses, have played the major role in shaping the gene content of the Drosophila Y, at least in the last ∼63 million years (My) (8, 9). Hence, the Drosophila Y chromosome seems to be evolving noncanonically (10) and is an ideal model to investigate the dynamics of gene gain on a nonrecombining Y chromosome.

The Drosophila Y chromosome has long been known to contain genes essential for male fertility (11, 12). Due to its heterochromatic state, progress in the molecular identification of the Y-linked single-copy genes has been slow. male fertility factor kl5 (kl-5), the first single-copy gene identified, was found serendipitously; it encodes a motor protein (dynein heavy chain) required for flagellar beating (13). More recently, a combination of computational and experimental methods identified 11 single-copy Y-linked genes among the unmapped sequence scaffolds produced by the Drosophila Genome Project (5–7). These genes have two striking features: (i) their closest paralogs are autosomal and not X linked, and (ii) they have male-specific functions, such as the beating of sperm flagella reported for the kl-5 gene (14). The most likely explanation for this pattern is that Y-linked genes were acquired from the autosomes and have been retained because they confer a specific fitness advantage to their carriers. An autosomal origin has previously been reported for a few Y-linked genes in humans and a repetitive gene on the Drosophila Y (4, 15). However, unequivocal evidence of the autosomal origin of Drosophila Y-linked genes, and of the specific mechanism that originated them, is lacking due to their antiquity. The 11 known single-copy genes (kl-2, kl-3, kl-5, ARY, WDY, PRY, Pp1-Y1, Pp1-Y2, Ppr-Y, ORY, and CCY) represent ancient duplications, with amino acid identities to the putative ancestors ranging from 30% to 74%, and poor (if any) alignment at the nucleotide level. Most of them have introns in conserved positions compared with their autosomal paralogs, ruling out retrotransposition and suggesting DNA-based duplication as the mechanism. The original size of these putative duplications is unknown, because the similarity between autosomal and Y-linked regions is restricted to one gene in each case. Flanking sequences and contiguous genes either were not duplicated or were subsequently mutated and deleted beyond recognition.

Here we describe flagrante delicto Y (FDY), a single copy Y-linked gene present only in D. melanogaster, and which is 98% identical at the nucleotide level to the autosomal gene vig2. Because its origin is very recent (it occurred after the split between D. melanogaster and Drosophila simulans, ∼4 Mya), it was possible to demonstrate that FDY arose from a DNA-based duplication of chromosome 3R to the Y: the duplicated segment spans 11 kb of autosomal sequence and includes five contiguous genes (vig2, Mocs2, CG42503, Clbn, and Bili); the last four genes became pseudogenes by rapid accumulation of deletions, point mutations, and transposable element insertions or by lack of expression. Thus, FDY unequivocally demonstrates that the Drosophila Y has acquired genes from autosomes. Several Y-linked genes such as kl-2, kl-3, and PRY are shared by distant Drosophila species that diverged ∼60 Mya, implying ancient acquisitions. FDY dates the more recent acquisition to ∼2 My, and hence strongly suggests that Drosophila Y has been continuously acquiring autosomal genes.

Results

Identification of FDY.

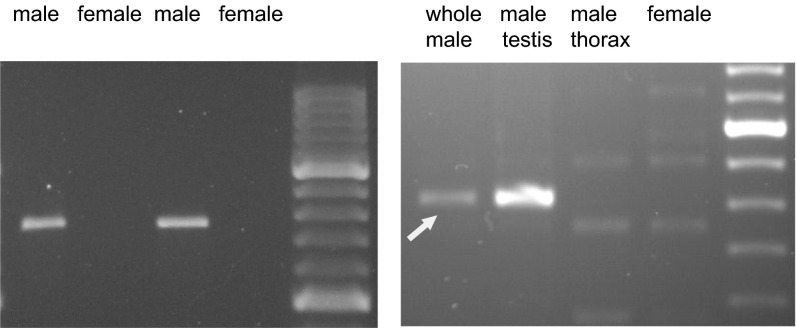

During the search for novel genes on the Drosophila Y chromosome (5, 6) we found a small unmapped scaffold in Release 2 of the Drosophila genome (AE002644) that had 98% nucleotide identity with region 96C1 of chromosome 3R (scaffold AE003750; Materials and Methods). When we performed PCR with primers specifically targeting AE002644, we observed amplification from male genomic DNA and not from female, a clear signature of Y linkage (Fig. 1, Left). This scaffold contains a fragment of a gene very similar to the vig2 gene (96.5% identity at the amino acid level). The few differences between vig2 and its Y-linked counterpart are mirrored in ESTs: five testis ESTs (accessions BF492105, BF505577, BF492579, BF488227, and BF492578) have exactly the Y-linked sequence variant, and the remaining 127 ESTs have the autosomal sequence variant (three from testis, 124 from other tissues). These results suggest that the Y-linked copy of vig2 has testis-restricted expression, whereas the autosomal parental gene has ubiquitous expression, which was confirmed by RT-PCR with primers specific to the Y-linked copy (Fig. 1, Right) and by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) (SI Appendix, Table S1). The Y-linked copy might be a pseudogene, but it does not seem to be the case: it is expressed (Fig. 1, Right), accounting for 21% of the vig2-like mRNA in testis (SI Appendix, Table S1), it has an intact ORF and splice junctions, and it has no premature stop codons. Additional evidence of functionality is presented in Results, Molecular Evolution of the FDY Region Genes. We conclude that the Y-linked copy of vig2 is a functional gene, which we named flagrante delicto Y because it provides direct evidence of the origin of Y-linked genes (below). Given their high sequence identity, FDY and vig2 most likely have a similar molecular function. The protein encoded by vig2 has mRNA and hyaluron-binding motifs and interacts with heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) through an RNA component; data from mutation analysis shows that vig2 is an enhancer of position effect variegation (PEV) and is involved with heterochromatin formation and heterochromatin-mediated gene silencing (16, 17). The Drosophila Y is large (41 Mbp), entirely heterochromatic, and abundantly transcribed in testis (18); it is possible that FDY, along with vig2, helps the proper organization of heterochromatin in cells of the testis.

Fig. 1.

PCR and RT-PCR of the FDY gene. (Left) PCR with primers targeting specifically the FDY gene (AE002644 scaffold), performed in two different strains (ISO1 and Oregon-R, respectively). Scaffold AE002644 was later withdrawn from GenBank, because it was erroneously considered a misassembly of the autosomal scaffold AE003750. (Right) RT-PCR with FDY-specific primers. The arrow marks the specific product (807 bp). Note that FDY expression is restricted to testis.

The FDY sequence is incomplete in Release 2, in WGS3 and Release 6 of the D. melanogaster genome. We obtained its full coding sequence by RT-PCR (accession KR781487). The recent PacBio MHAP assembly (19, 20) covered its full sequence, and we were able to confirm that the position and sequence of the intron is conserved between FDY and vig2, showing that FDY originated through a DNA-based duplication, rather than retrotransposition. Fortunately, as described in the next section, the PacBio assemblies covered not only FDY, but also substantial flanking regions.

The FDY Region.

To ascertain the size of the duplicated fragment, we performed a BlastN search using 100 kb surrounding the vig2 gene as a query. Using Release 2 this search yields only scaffold AE02644, but with the improved assembly WGS3 (21), we found 11 kb of duplicated sequence from chromosome 3R, fragmented in 11 scaffolds (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). These 11 scaffolds proved to be Y linked and contain pieces of four additional autosomal genes. These four genes (Mocs2, CG42503, Clbn, and Bili) are contiguous to vig2 on chromosome 3R, and their Y-linked copies became pseudogenes.We spent many years trying to finish the FDY region, manually assembling the sequence variants found in the Sanger traces (using a strategy similar to the one in ref. 22), using PCR and long-PCR to close gaps, and, in collaboration with S. Celniker and C. Kennedy from the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project (BDGP), identifying suitable 10-kb clones from the original D. melanogaster WGS project for sequencing (23). The BDGP effort was partially successful, resulting in the scaffold CP000341, which was incorporated into Releases 5 and 6 of the D. melanogaster genome (23, 24). We also obtained a preliminary assembly of the whole FDY region, using the methods described above. However, both scaffold CP000341 and our preliminary assembly have gaps: it was not possible to fully assemble the FDY region due to the very high identity of the repeats. As the recent PacBio MinHash Alignment Process (MHAP) assembly of D. melanogaster (19, 20) accurately reconstructed a very challenging region of the Y chromosome (25), we decided to use it to investigate the FDY region. We found a 207-kb contig (accession JSAE01000195) that seems to contain the complete FDY region, spanning FDY itself (with a complete and perfect sequence), and the four contiguous genes, in the same order in which they occur on chromosome 3R (Fig. 2; validation of this assembly is deferred to Results, Validation of the MHAP Assembly of the FDY Region). The Y-linked copies of three genes (Mocs2, Clbn, and Bili) clearly became pseudogenes, for they have frame-shifting indels and transposable element insertions that disrupted their coding regions. The Y-linked copy of CG42503 seems to be a pseudogene too, because it is not significantly expressed (SI Appendix, Table S1), although its small coding region (273 bp) is intact (see Results, Molecular Evolution of the FDY Region Genes). In contrast, FDY has only one small, in-frame coding indel, and is expressed in larvae, pupae, and adult males, most likely in the testis (Fig. 1, Right and SI Appendix, Table S1). In sum, the only gene from the Y-linked duplicated region that remained functional appears to be FDY.

Fig. 2.

Genomic structure of the FDY region of the Y chromosome and its surroundings. (Top) Whole contig JSAE01000195 (207 kb) from the MHAP PacBio assembly (19, 20) showing its repeat content (57); blue, non-LTR retrotransposons (mostly TART); gray, LTR-retrotransposons (Stalker, Gypsy, etc.); magenta, DNA transposons (mostly Protop). Note the small islands of nonrepetitive DNA (thin line), all of which are 3R-derived sequence. Repetitive elements account for 92% of the sequence. (Bottom) Annotation of the FDY region (55 kb; coordinates 70k–126k of contig JSAE01000195). The asterisk marks the tiny CG42503-ψ1 pseudogene. Triangles above the line indicate transposable element insertions, and triangles below the line point to smaller insertions and deletions that disrupt the coding regions. Partial duplications of Clbn-ψ4 generated three additional Clbn copies (Clbn-ψ1, Clbn-ψ2, and Clbn-ψ3) that got inserted in the middle of the Mocs2-ψ1 pseudogene; we used the Clbn-ψ4 sequence in all analyses. Repetitive elements account for 75% of the sequence. Note the lack of disruptions in the FDY gene.

The ends of the duplicated region on 3R did not give any clue to the mechanism involved: the left end falls in a short intergenic region between the CG31510 and vig2 genes, whereas the right end is in the middle of the Bili gene. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the duplicated region was larger than 11 kb and had been reduced afterward by deletions. The specific site of the insertion on the Y chromosome also did not provide any clue: the FDY region is flanked on the left and on the right by transposable elements (DMRT_1B and TART-A, respectively). The FDY region spans 55 kb and is packed with repeats: the 3R-derived sequence forms small pockets of nonrepetitive sequence, amid a sea of transposable elements (mostly retrotransposons), which account for 75% of its length (Fig. 2).

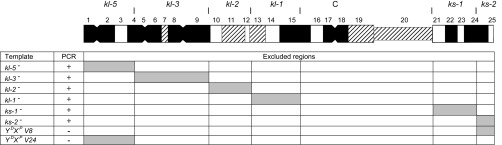

We mapped the cytological region of the insertion with a collection of X-ray induced X–Y translocations that generate males lacking defined regions of the Y chromosome (11). PCR with DNA extracted from these males showed that the FDY insertion is located in the broad vicinity of the Y centromere, between the heterochromatic bands h15 and h20 (Fig. 3). As this region does not contain any gene essential for male fertility (11), we can conclude that FDY is not essential for male fertility. Besides FDY, two other protein coding genes are located in this region: Pp1-Y2 (6, 26) (SI Appendix, Section 1) and the multicopy Mst77Y (25).

Fig. 3.

FDY mapping with PCR and deleted Y chromosomes. Males lacking defined regions of the Y chromosome were generated by crossing fertile X–Y translocations (11) as detailed in SI Appendix, Section 1 and used as templates for PCR with FDY-specific primers. (Top) Cytogenetic map of the Y chromosome (adapted from ref. 58), showing the regions that contain the fertility factors (kl-5 to ks-2), the heterochromatic bands (h1 to h25), and the centromere (“C”). The vertical lines that delimit the fertility factor regions are the breakpoints of the fertile X–Y translocations. (Bottom) PCR with FDY-specific primers, showing the DNA templates (e.g., kl-5− are males lacking the kl-5 region), the PCR result, and the regions that are excluded as possible FDY locations. The last two templates are males carrying only the tips of the Y chromosome; they confirm that FDY is not located there, and hence must be located in the broad vicinity of the Y centromere, between the heterochromatic bands h15 and h20 (SI Appendix, Section 1).

Finally, an interesting observation that deserves further investigation is the seemingly promiscuous transcription of Y-linked genes/pseudogenes of the FDY region in embryos (SI Appendix, Table S1): 3–11% of the gene expression came from the Y-linked copy in all five genes. This embryonic expression is absent from all other Y-linked genes (e.g., ARY; SI Appendix, Table S1), which are expressed only in pupae, adult males, and testis, and possibly reflects an incomplete heterochromatinization of this young insertion or read-through transcription from the flanking transposable elements.

Phylogenetic Analysis and the Age of FDY.

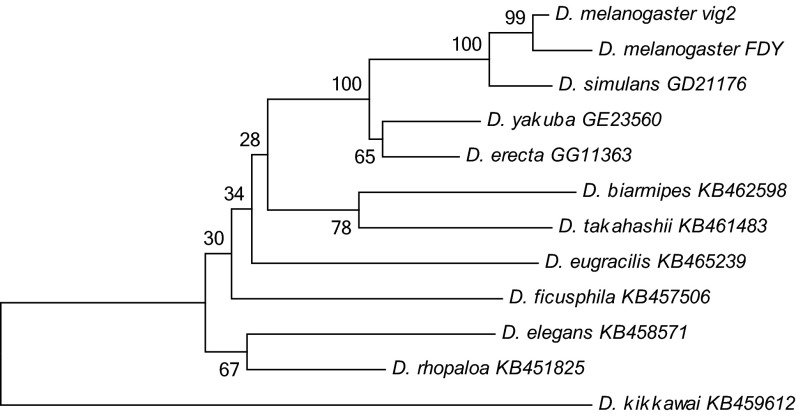

The remarkably high sequence similarity between FDY and vig2 indicates that the duplication is recent. To date this event, we performed a phylogenetic analysis of vig2 orthologs from closely related species (Fig. 4). This analysis strongly suggests that FDY originated after the split between D. melanogaster and D. simulans, which dates 1.1–6.3 Mya (27–29); for the sake of simplicity we will assume 4 Mya. The same result was obtained for the four other genes of the FDY region (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Consistent with these results, a search of vig2 orthologs in the genome sequences of D. simulans, Drosophila sechellia, Drosophila erecta, Drosophila yakuba, Drosophila kikkawai, and Drosophila ananassae yielded only the autosomal copy. To date more precisely the origin of FDY, we applied the RelTime method (30) to the data shown in Fig. 4; we found 1.64 Mya (95% confidence interval: 0.21–3.08 Mya). As other molecular clock estimates, this value should be taken with caution: it depends on the calibration (we used 4 Mya as the D. melanogaster/D. simulans split), and may be affected by nonuniform rates of evolution. Taken together, the above results show that FDY originated after the split between D. melanogaster and D. simulans (4 Mya) and suggest that it has approximately half the age of this split.

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of the FDY gene and its homologs. FDY is most closely related to the D. melanogaster paralog vig2, with 100% bootstrap support. The evidence that FDY and D. melanogaster vig2 cluster together is further strengthened by an 18-bp coding deletion exclusively shared by them. The phylogeny was inferred using the maximum likelihood method and the TN93 + G model (55, 59). D. kikkawai was used as the outgroup (51).

FDY seems to be present in all D. melanogaster Y chromosomes, based on a sample of 24 isofemale lines from Europe (Vienna, Austria), North America (State College, US), and Africa (Congo). Recurrent duplication can be ruled out because the PCR assay used one primer inside the vig2-like region and the other inside a flanking region in the Y, and it is nearly impossible that two independent duplications would put a copy of vig2 exactly at the same location on the Y chromosome. These results imply that the vig2 duplication occurred once (less than 4 Mya), and then became fixed in the whole species.

Molecular Evolution of the FDY Region Genes.

The evidence presented in Results, The FDY Region strongly suggests that FDY is functional, and that the other four genes are pseudogenes. In principle this might be tested by estimating the dN/dS ratios; values significantly smaller than 1 imply purifying selection (and hence, functionality), whereas values around 1 suggest pseudogenization (31). If we run the dN/dS tests in the five Y-linked genes, the null hypothesis (dN = dS) was not rejected for FDY (P > 0.7) and was rejected for the pseudogene Clbn-ψ4 (P = 0.02; SI Appendix, Table S2), a seemingly nonsensical pattern. However, these tests are suspicious due to serious violations of its assumptions of homogeneous substitution process and stationary base composition. The branch lengths of the trees suggest an accelerated rate of substitution along the Y chromosome copies (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S2), and this was confirmed by the Tajima relative rates test (vig2/FDY: χ2 = 9.14, df = 1, P = 0.0025) (32). Furthermore, the disparity index test (27) showed that three of the five genes violate the assumptions of homogeneous substitution process (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Namely, within D. melanogaster, the Y copy branches exhibit an excess of GC → AT substitutions compared with AT → GC (72: 20, across all five genes), whereas the autosomal copies have the expected equilibrium (9:7; SI Appendix, Fig. S3). This substitution bias is the probable cause of the previously found pattern that Drosophila heterochromatic genes in general (including Y-linked ones) are AT rich (33, 34). Unfortunately all available codon substitution models assume stationary base composition, and it has been shown that they are sensitive to violations of this assumption (35). So currently it is not possible to perform dN/dS analysis for the FDY region genes.

We performed an alternative test of functionality that is insensitive to nonstationarity as follows (Table 1). As commented before, FDY has an intact ORF (as well as the small CG42503), but the other coduplicated genes have several disrupting indels. The absence of disrupting indels in FDY might be a chance event, or, alternatively, might de due to purifying selection (i.e., FDY would be functional). To test these hypotheses, we performed a Poisson regression to compare the number of disrupting indels across the five Y-linked copies, using the coding sequence length as the exposure (longer genes have a higher chance of indel events). As expected, the effect of coding sequence length is statistically significant (P = 0.002). Interestingly, the residual deviance is also statistically significant (χ2 = 8.498, 3 df, P = 0.037), implying heterogeneity among the genes in the number of disrupting indels; analysis of the residuals shows that FDY is the outlier (Table 1). Hence we can reject the hypothesis that the lack of disrupting indels in FDY is due to chance; it is most likely explained by purifying selection. On the other hand, we could not reject the null hypothesis for CG42503-ψ1: due to its small size, it was expected to get only one indel, so the preservation of its ORF may well be a chance event. Of course it may be due to purifying selection, but the lack of expression in most stages/tissues (SI Appendix, Table S1) suggests that the Y-linked copy of CG42503 is a pseudogene as well.

Table 1.

Evidence of purifying selection in FDY inferred from indel patterns

| Gene | Exposure* | Observed indels | Expected indels† | Standardized residual |

| Mocs2-ψ1 | 1104 | 3 | 1.85 | +0.89 |

| FDY | 1239 | 0 | 2.06 | −2.33‡ |

| Clbn-ψ4§ | 2979 | 8 | 8.28 | −0.68 |

| Bili-ψ1 | 1106 | 4 | 1.85 | +1.57 |

| CG42503-ψ1 | 273 | 0 | 0.95 | −1.63 |

Poisson regression exposure was set equal to the CDS length of the autosomal paralog, except for Bili-ψ1. The full CDS length of Bili is 2,487 bp, but only its N-terminal (1,106 bp) was found in the Y chromosome. We conservatively assumed that the Bili duplication was incomplete; hence the exposure was set to 1,106 and the terminal deletion was not counted.

Assuming a constant stochastic rate of indels, the expected and standardized residual counts of indels were derived from a Poisson regression model.

P < 0.05.

Clbn-ψ4 is the longest pseudogene of Clbn.

Validation of the MHAP Assembly of the FDY Region.

Up to this moment we have implicitly assumed that the MHAP PacBio assembly (i.e., contig JSAE01000195) is an accurate reconstitution of the FDY region. Here we provide support for this assumption. First, the three PacBio assemblies, which used the same reads but three different algorithms to assemble them, are essentially identical in this region (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). More importantly, direct comparison of contig JSAE01000195 with the semifinished scaffold CP000341 and with our preliminary assembly, which are Sanger-based and completely independent from MHAP, shows that the JSAE01000195 contig is colinear with both (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), which excludes major misassemblies (e.g., a chimeric fusion with sequences from other parts of the genome). Finally, comparison with the Illumina reads (again, completely independent), which can detect small-scale assembly errors (e.g., indels and mismatched bases), did not detect any error in the FDY region of contig JSAE01000195 (SI Appendix, Table S3). Note that Illumina reads did detect errors in the two other PacBio assemblies, so the zero error in the MHAP assembly was not due to lack of power. It seems that we can safely conclude that the MHAP assembly accurately reconstitutes the FDY region of the D. melanogaster genome.

We also examined the contig JSAE01000195 (and its equivalent in the other PacBio assemblies) outside the FDY region, searching for other genes or features that may give a more precise location of the insertion. All three assemblies have errors in this broader region (SI Appendix, Table S4) so the results must be interpreted with caution. Contig 0340_00 (FALCON assembly; 359 kb) is the largest and contains two additional features, which unfortunately are not very informative: a small pseudogene of gene Ptp61F, and a 82-kb block (positions 1–82 kb of the contig) of degenerated Tart-A transposons (Tart is a telomeric transposon, but is also known to occur in internal regions of the Y chromosome) (36, 37).

Discussion

We have shown that FDY is a functional gene acquired by the D. melanogaster Y chromosome after the split from D. simulans, less than 4 Mya. Due to its young age, it was possible to precisely determine the mechanism of its origin: a duplication of 11 kb of chromosome 3R, encompassing vig2 (FDY's parent gene), and four other contiguous genes. These four genes became pseudogenes, as indicated by the accumulation of frame-shifting indels and transposable element insertions that disrupted their coding regions, and by the lack of significant mRNA expression. On the other hand, the coding region of FDY remained intact, most likely due to purifying selection, and it accounts for 21% of the vig2-like mRNA in testis. In sum, the only gene from the duplicated region that remained functional is FDY. There is little doubt that in a few million years the seven pseudogenes (Mocs2-ψ1, CG42503-ψ1, Clbn-ψ1–Clbn-ψ4, and Bili-ψ1) will become mutated beyond recognition, and thus, the only sign of the autosomal origin of FDY will be the protein similarity to an autosomal gene (vig2). This pattern precisely matches the present situation of the other Y-linked genes (5–7).

The vig2 gene (and presumably FDY) is involved with heterochromatin formation and function (16, 17). As all Drosophila Y-linked genes studied to date, FDY is expressed primarily in testis, and in most cases, the parent genes themselves were already testis restricted before moving to the Y chromosome (9). FDY's parent gene vig2 is an interesting exception: it is ubiquitously expressed and is strongly expressed in females (SI Appendix, Table S1) (38). Hence a female-biased gene (vig2) gave rise to a testis-biased gene (FDY). This seems to be a case of gene duplication followed by neofunctionalization (39, 40), the first reported, to our knowledge, for the Drosophila Y. However, due to the recency of the duplication, the evolutionary fates of vig2 and FDY are unclear (e.g., it is not known if vig2 will lose its testis expression).

The available evidence strongly suggests that the vig2 duplication occurred once, ∼2 Mya, and then became fixed in the whole species. There is no recombination on the Y chromosome, implying that this sweep was chromosome-wide. Indeed, each Y-linked gene acquired from an autosome provides evidence for such a hard, chromosome-wide sweep. The lack of recombination precludes the use of population genetic methods that might pinpoint the cause of FDY fixation (e.g., ref. 41) and hence we cannot formally exclude the hypotheses that the sweep occurred by random genetic drift or by positive selection on another gene. However, the fact that FDY retained its function (whereas the coduplicated genes degenerated) indicates that FDY is under purifying selection and suggests that the fixation could well have been driven by natural selection.

The primary focus of the population genetic theory of the Y chromosome is the degeneration and loss of genes (1–3). Although this focus appears to be appropriate for the mammalian Y, the Drosophila Y has been continually evolving through the accumulation of (usually) male-related genes from the autosomes: the CCY and ARY genes were acquired by the Y chromosome ∼62 Mya (8), whereas FDY is at most 4 My old. Furthermore, gene gain, instead of gene loss, has been the dominating force of Drosophila Y evolution, at least in the last 63 My (8). It is also possible that the Drosophila Y actually is a modified B (“supernumerary”) chromosome instead of an X homolog, and hence may have never suffered massive gene loss (10, 42). Thus, at least for 63 My, the Drosophila Y, with its continuous gain of genes and functions, has been telling a story that contrasts sharply with that of the mammalian Y.

Finally, we emphasize the utility of PacBio technology in dealing with difficult genomic regions: as was the case with the Mst77Y region (25), PacBio produced a seemingly error-free assembly of the FDY region, something that has eluded us for years of hard work.

Materials and Methods

D. melanogaster Genome and RNA Sequences.

The initial identification of the FDY gene was carried out with Release 2 (ftp://ftp.flybase.net/genomes/dmel/dmel_r2.0/fasta/), which was the current assembly in 2001. When it became available, we switched to the WGS3 assembly (ftp://ftp.fruitfly.org/pub/download/compressed/WGS3_het_genomic_dmel_RELEASE3-0.FASTA.gz), which has a better representation of heterochromatic regions (21). The final analysis was done using the PacBio MHAP assembly (19, 20); NCBI accession JSAE00000000.1). We also used two preliminary PacBio assemblies (see ref. 25 for details): PBcR (downloaded from cbcb.umd.edu/software/pbcr/dmel_cons_asm.tar.gz) and FALCON (downloaded from datasets.pacb.com.s3.amazonaws.com/2014/Drosophila/reads/dmel_FALCON_diploid_assembly.tgz). Illumina RNA-seq reads produced by the modENCODE project (43) were used to assess gene expression of FDY and its flanking genes in embryo, larvae, pupae, and adults (accession nos. are listed in SI Appendix, Section 3). Maria Vibranovski (University of São Paulo, São Paulo) kindly gave us access to a testis RNA-seq library, used for the same purpose. To measure gene expression, RNA-seq reads were aligned to the PacBio MHAP assembly with bwa (44), and the bam output file was processed with eXpress (45). All assemblies and reads came from the reference genomic strain ISO1 (46). The program versions and parameters used in these and other procedures are detailed in SI Appendix, Section 2.

Misassembly Detection Using Illumina Reads.

As detailed in ref. 25, we used a large dataset of 100-bp paired-end Illumina reads from ISO1 adult males, which was produced by Casey Bergman and coworkers (47) (accession ERX645969), to assess the reliability of the PacBio assemblies. Briefly, we compared the PacBio contigs with the Illumina reads with two complementary approaches. First, the reads were aligned to the PacBio assemblies using bwa (44); misassemblies were detected as assembly regions with discrepancies to the Illumina reads, in particular regions in which no read aligns (“zero coverage regions”). Second, we used the YGS program (Dataset S1), which decomposed both the assembled genome and the Illumina reads in k-mers (15-mers, in this case) and compared the two lists, to identify in the genome the k-mers that are not matched by the Illumina derived k-mers (9). Given the inherently low error rate of Illumina reads, discrepancies between them and the assembled genome such as zero coverage regions and unmatched k-mers almost certainly are due to assembly errors.

Identification of FDY.

The gene was found during the search for D. melanogaster Y-linked genes among unmapped scaffolds (“armU”) produced by the Drosophila Genome project (48). The methods we used were described previously (6). Briefly, a local database of unmapped scaffolds (armU or “chromosome U”) was searched with TblastN for protein-coding scaffolds. Candidate scaffolds were tested for Y-linkage by PCR, using DNA from males and virgin females as templates; Y-linked scaffolds are PCR positive only in males. Mapping of Y-linked scaffolds to specific regions of the Y chromosome and RT-PCR were done as described previously (5, 6), and detailed in SI Appendix, Section 1. The full coding sequence of the FDY gene was obtained by RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing (accession KR781487); the full mRNA sequence (accession BK009307) was assembled with Bowtie2/TopHat/Cufflinks (49), using the PacBio MHAP genome assembly as a reference (19, 20) and the modENCODE's RNA-seq data (adult males; accessions listed in SI Appendix, Section 3). Sanger sequencing was done at Macrogen (Korea) and the Cornell DNA sequencing core facility.

Phylogenetic Analysis.

The phylogenetic analysis of vig2 orthologs (Fig. 4) was performed with the full coding sequences from all sequenced species more closely related to D. melanogaster (namely, the “oriental subgroups”) (50) and used as the outgroup the more distantly related D. kikkawai (montium subgroup). The coding sequences of vig2 (D. melanogaster) and its orthologs in D. simulans, D. yakuba, and D. erecta were downloaded from FlyBase (38). The genomes of the remaining species (Drosophila eugracilis, Drosophila takahashii, Drosophila biarmipes, Drosophila ficusphila, Drosophila rhopaloa, Drosophila elegans, and, as an outgroup, D. kikkawai) were recently sequenced (51) and have not yet been annotated, so the sequence of the vig2 orthologs were extracted from the corresponding scaffolds (e.g., KB462598 in the case of D. biarmipes) using GeneWise (52).

Along with FDY (accession KR781487), these sequences were aligned with Muscle (53) as implemented in MEGA6 (54); the aligned sequences (Dataset S2) were manually inspected for reading frame consistency (no correction was needed). The phylogeny was inferred with the maximum likelihood method, and its statistical support was obtained with the bootstrap test (55); both procedures were carried with the MEGA6 software (54).

The phylogenetic analysis of the four other genes that were coduplicated with vig2 (CG42503, Mocs2, Clbn, and Bili; SI Appendix, Fig. S2) followed the same general procedure used for vig2, except that the coding sequence of the Y-linked copies was annotated by sequence similarity with the autosomal parental genes (accessions BK009348–BK009355) because they are not expressed. In most cases these Y-linked copies contain large transposable element insertions and out-of-frame deletions, that were manually corrected (i.e., removed or filled with gaps) to preserve the reading frame consistency (alignments available in Dataset S3). To avoid using a large number of unannotated genes, we restricted this analysis to D. melanogaster, D. simulans, and D. yakuba.

dN/dS Tests.

The HyPhy package (56) was used to obtain maximum likelihood estimates of substitution rates at synonymous and nonsynonymous sites along the branches of the tree, and to perform the dN/dS tests, as documented in Dataset S4. The sequence alignments are the same mentioned above (Dataset S3) and the user-specified tree was taken from Figure 1A of ref. 51 (that tree was based on a large number of genes).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Vibranovski, C. Bergman, and the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project for access to unpublished data; M. Vibranovski, R. Hoskins, S. Celniker, C. Kennedy, J. Carlson, S. Galasinski, B. Wakimoto, J. Yasuhara, G. Sutton, M. Kuhner, J. Felsenstein, and C. Santos for help in various steps of the work; and B. Bitner-Mathe, R. Ventura, the members of the A.B.C. and A.G.C. laboratories, and two reviewers for many valuable comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), FAPERJ, and CAPES (to A.B.C.), and National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM64590 (to A.G.C. and A.B.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: Nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper are available in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under the accession nos. TPA: BK009348–BK009355, TPA: BK009307, and KR781487.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1516543112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bull JJ. 1983. Evolution of Sex Determining Mechanisms (Benjamin/Cummings Advanced Book Program, Menlo Park, CA)

- 2.Rice WR. Evolution of the Y sex chromosome in animals. Bioscience. 1996;46(5):331–343. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D. The degeneration of Y chromosomes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2000;355(1403):1563–1572. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skaletsky H, et al. The male-specific region of the human Y chromosome is a mosaic of discrete sequence classes. Nature. 2003;423(6942):825–837. doi: 10.1038/nature01722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carvalho AB, Lazzaro BP, Clark AG. Y chromosomal fertility factors kl-2 and kl-3 of Drosophila melanogaster encode dynein heavy chain polypeptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(24):13239–13244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230438397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carvalho AB, Dobo BA, Vibranovski MD, Clark AG. Identification of five new genes on the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(23):13225–13230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231484998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vibranovski MD, Koerich LB, Carvalho AB. Two new Y-linked genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2008;179(4):2325–2327. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.086819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koerich LB, Wang X, Clark AG, Carvalho AB. Low conservation of gene content in the Drosophila Y chromosome. Nature. 2008;456(7224):949–951. doi: 10.1038/nature07463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carvalho AB, Clark AG. Efficient identification of Y chromosome sequences in the human and Drosophila genomes. Genome Res. 2013;23(11):1894–1907. doi: 10.1101/gr.156034.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernardo Carvalho A, Koerich LB, Clark AG. Origin and evolution of Y chromosomes: Drosophila tales. Trends Genet. 2009;25(6):270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennison JA. The genetic and cytological organization of the Y-chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1981;98(3):529–548. doi: 10.1093/genetics/98.3.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bridges CB. Non-disjunction as proof of the chromosome theory of heredity. Genetics. 1916;1(1):1–52. doi: 10.1093/genetics/1.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gepner J, Hays TS. A fertility region on the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster encodes a dynein microtubule motor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(23):11132–11136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein LSB, Hardy RW, Lindsley DL. Structural genes on the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79(23):7405–7409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalmykova AI, Shevelyov YY, Dobritsa AA, Gvozdev VA. Acquisition and amplification of a testis-expressed autosomal gene, SSL, by the Drosophila Y chromosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(12):6297–6302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gracheva E, Dus M, Elgin SC. Drosophila RISC component VIG and its homolog Vig2 impact heterochromatin formation. PLoS One. 2009;4(7):e6182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneiderman JI, Goldstein S, Ahmad K. Perturbation analysis of heterochromatin-mediated gene silencing and somatic inheritance. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(9):e1001095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reugels AM, Kurek R, Lammermann U, Bünemann H. Mega-introns in the dynein gene DhDhc7(Y) on the heterochromatic Y chromosome give rise to the giant threads loops in primary spermatocytes of Drosophila hydei. Genetics. 2000;154(2):759–769. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.2.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berlin K, et al. Assembling large genomes with single-molecule sequencing and locality-sensitive hashing. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(6):623–630. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim KE, et al. Long-read, whole-genome shotgun sequence data for five model organisms. Sci Data. 2014;1:140045. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2014.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoskins R, et al. 2002. Heterochromatic sequences in a Drosophila whole genome shotgun assembly. Genome Biol 3(12):RESEARCH0085.

- 22.Arner E, Tammi MT, Tran AN, Kindlund E, Andersson B. DNPTrapper: An assembly editing tool for finishing and analysis of complex repeat regions. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoskins RA, et al. Sequence finishing and mapping of Drosophila melanogaster heterochromatin. Science. 2007;316(5831):1625–1628. doi: 10.1126/science.1139816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoskins RA, et al. The Release 6 reference sequence of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome Res. 2015;25(3):445–458. doi: 10.1101/gr.185579.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krsticevic FJ, Schrago CG, Carvalho AB. Long-read single molecule sequencing to resolve tandem gene copies: The Mst77Y region on the Drosophila melanogaster Y chromosome. G3 (Bethesda) 2015;5(6):1145–1150. doi: 10.1534/g3.115.017277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abad JP, et al. Genomic and cytological analysis of the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster: Telomere-derived sequences at internal regions. Chromosoma. 2004;113(6):295–304. doi: 10.1007/s00412-004-0318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Obbard DJ, et al. Estimating divergence dates and substitution rates in the Drosophila phylogeny. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29(11):3459–3473. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura K, Subramanian S, Kumar S. Temporal patterns of fruit fly (Drosophila) evolution revealed by mutation clocks. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21(1):36–44. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lachaise D, et al. Historical biogeography of the Drosophila melanogaster species subgroup. Evol Biol. 1988;22:159–225. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamura K, et al. Estimating divergence times in large molecular phylogenies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(47):19333–19338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213199109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Z, Bielawski JP. Statistical methods for detecting molecular adaptation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2000;15(12):496–503. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01994-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tajima F. Simple methods for testing the molecular evolutionary clock hypothesis. Genetics. 1993;135(2):599–607. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.2.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Díaz-Castillo C, Golic KG. Evolution of gene sequence in response to chromosomal location. Genetics. 2007;177(1):359–374. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.077081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh ND, Koerich LB, Carvalho AB, Clark AG. Positive and purifying selection on the Drosophila Y chromosome. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31(10):2612–2623. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bay RA, Bielawski JP. Inference of functional divergence among proteins when the evolutionary process is non-stationary. J Mol Evol. 2013;76(4):205–215. doi: 10.1007/s00239-013-9549-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agudo M, et al. Centromeres from telomeres? The centromeric region of the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster contains a tandem array of telomeric HeT-A- and TART-related sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(16):3318–3324. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.16.3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berloco M, Fanti L, Sheen F, Levis RW, Pimpinelli S. Heterochromatic distribution of HeT-A- and TART-like sequences in several Drosophila species. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110(1-4):124–133. doi: 10.1159/000084944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.dos Santos G, et al. FlyBase Consortium FlyBase: Introduction of the Drosophila melanogaster Release 6 reference genome assembly and large-scale migration of genome annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D690–D697. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lynch M. The Origins of Genome Architecture. Sinauer; Sunderland, MA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J. In: Gene Duplication. Princeton Guide to Evolution. Losos J, editor. Princeton Univ Press; Princeton, NJ: 2013. pp. 397–405. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nurminsky DI, Nurminskaya MV, De Aguiar D, Hartl DL. Selective sweep of a newly evolved sperm-specific gene in Drosophila. Nature. 1998;396(6711):572–575. doi: 10.1038/25126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hackstein JHP, Hochstenbach R, Hauschteck-Jungen E, Beukeboom LW. Is the Y chromosome of Drosophila an evolved supernumerary chromosome? BioEssays. 1996;18(4):317–323. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daines B, et al. The Drosophila melanogaster transcriptome by paired-end RNA sequencing. Genome Res. 2011;21(2):315–324. doi: 10.1101/gr.107854.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roberts A, Pachter L. Streaming fragment assignment for real-time analysis of sequencing experiments. Nat Methods. 2013;10(1):71–73. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brizuela BJ, Elfring L, Ballard J, Tamkun JW, Kennison JA. Genetic analysis of the brahma gene of Drosophila melanogaster and polytene chromosome subdivisions 72AB. Genetics. 1994;137(3):803–813. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.3.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gutzwiller F, et al. 2015. Dynamics of Wolbachia pipientis gene expression across the Drosophila melanogaster life cycle. arXiv:1505.05782.

- 48.Adams MD, et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287(5461):2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trapnell C, et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(3):562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kopp A, True JR. Phylogeny of the Oriental Drosophila melanogaster species group: A multilocus reconstruction. Syst Biol. 2002;51(5):786–805. doi: 10.1080/10635150290102410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen ZX, et al. Comparative validation of the D. melanogaster modENCODE transcriptome annotation. Genome Res. 2014;24(7):1209–1223. doi: 10.1101/gr.159384.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Birney E, Durbin R. Using GeneWise in the Drosophila annotation experiment. Genome Res. 2000;10(4):547–548. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.4.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Felsenstein J. Inferring Phylogenies. Sinauer; Sunderland, MA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pond SL, Frost SD, Muse SV. HyPhy: Hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(5):676–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kohany O, Gentles AJ, Hankus L, Jurka J. Annotation, submission and screening of repetitive elements in Repbase: RepbaseSubmitter and Censor. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:474. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gatti M, Pimpinelli S. Cytological and genetic analysis of the Y-chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. 1. Organization of the fertility factors. Chromosoma. 1983;88(5):349–373. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tajima F, Nei M. Estimation of evolutionary distance between nucleotide sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 1984;1(3):269–285. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.