Abstract

Introduction

Minority stress processes have been shown to have significant associations with negative mental health outcomes among sexual minority populations. Given that adversity may be experienced growing up as a sexual minority in heteronormative, if not heterosexist, environments, our research on resilience among sexual minority male youth proposes that positive identity development may buffer the effects of a range of minority stress processes.

Methods

An ethnically diverse sample of 200 sexual minority males ages 16–24 (mean age, 20.9 years) was recruited using mixed recruitment methods. We developed and tested two new measures: concealment stress during adolescence and sexual minority-related positive identity development. We then tested a path model that assessed the effects of minority stressors, positive identity development, and social support on major depressive symptoms.

Results

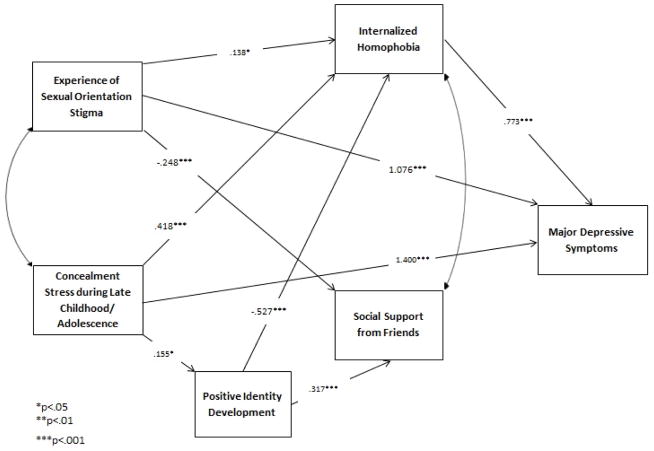

Experience of stigma was associated with internalized homophobia (β=.138, p<.05) and major depressive symptoms (β=1.076, OR=2.933, p<.001), and internalized homophobia partially mediated experience’s effects on major depression (β=.773, OR=2.167, p<.001). Concealment stress was associated with positive identity development (β=.155, p<.05) and internalized homophobia (β=.418, p<.001), and positive identity development partially mediated concealment stress’s effects on internalized homophobia (β=−.527, p<.001). Concealment stress demonstrated a direct effect on major depression (β=1.400, OR=4.056, p<.001), and indirect paths to social support through positive identity development.

Conclusions

With these results, we offer an exploratory model that empirically identifies significant paths among minority stress dimensions, positive identity development, and major depressive symptoms. This study helps further our understanding of minority stress, identity development, and resources of resilience among sexual minority male youth.

Keywords: minority stress, identity development, resilience, gay, bisexual, sexual minority youth, adolescence

INTRODUCTION

Sexual minorities (lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons) in the U.S. experience health disparities in comparison to the general population (Herek & Garnets, 2007; Mays & Cochran, 2001; Meyer 2003, 2007; Stall, Friedman, & Catania, 2008; Stall, et al., 2001). Population-based studies and meta-analyses have shown these disparities to develop early, as sexual minority youth also exhibit significant health disparities compared to their heterosexual counterparts (Coker, Austin, & Schuster, 2010; Marshal, et al., 2008; Saewyc, 2011). Analyses of social determinants of health have pointed to the experience of social isolation, discrimination and stigma based on sexual orientation to be a significant contributor to negative health and mental health outcomes among sexual minority youth (Almeida, Johnson, Corliss, Molnar, & Azrael, 2009; Hatzenbuehler, 2011), and among young gay and bisexual males in particular (Bauermeister, 2014; Bauermeister, 2014; Garofalo & Harper, 2003; Huebner, Rebchook, & Kegeles, 2004; Wong, Weiss, Ayala, & Kipke, 2010).

The minority stress framework proposes that mental health disparities among sexual minority populations may be explained by the stress produced by living in heterosexist social environments characterized by stigma and discrimination directed toward lesbian, gay and bisexual persons (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 1995, 2003; Meyer & Dean, 1998). Within contexts where stigma and discrimination are present, social theorists have noted that individuals may experience greater stress, conflict and alienation due to dominant social expectations and norms (Allport, 1954; Goffman, 1963; Link & Phelan, 2001). Although stress theory has emphasized external events of discrimination and concealment of stigmatized identity as stressors, minority stress has expanded this view to include the internalization of stigmatized attitudes among members of sexual minority groups. A range of pathogenic stress processes may thereby produce negative mental health effects individuals through the experience of stigma, prejudicial events and discrimination, fear of discrimination and resultant self-monitoring and stress associated with concealing one’s sexual orientation, as well as the internalization of negative attitudes and social values within stigmatized individuals themselves (Meyer, 1995; 2003).

Resilience among sexual minority youth is often proposed to emerge as adolescents are developing their personal sense of identity, with the assumptions that adversity is experienced through the reality of growing up as a sexual minority in heteronormative, if not heterosexist, environments (D’Augelli & Hershberger, 1993; DiFulvio, 2011; Rosario, Hunter, Maguen, Gwadz, & Smith, 2001; Russell, 2005). Investigations into resilience among sexual minority youth need to consider how youth adaptively respond to discrimination and marginalization based on their sexual orientation identity to better “understand the multiple ways in which identity, group membership, and ideological commitment situate people’s health behaviors and mental health” (Wexler, Di Fluvio, & Burke, 2009, p. 566). Of particular interest to our research on resilience among sexual minority male youth is the ways in which positive identity development may buffer the effects of a range of minority stress processes.

Minority Stress Processes and Sexual Minority Male Youth

A range of pathogenic minority stress processes have been shown to have significant associations with negative mental health outcomes among sexual minority male youth. The experience of sexual orientation stigma may take the form of bullying, verbal abuse, violence, and social marginalization, and may emanate from diverse sources including, family, peers, schools, and communities (Almeida, et al., 2009; Coker, et al., 2010; Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009). Young males who experience discrimination and victimization due to their sexual orientation have been shown to be more likely to report psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and suicidality in multiple studies (Almeida, et al., 2009; Coker, et al., 2010; Hightow-Weidman, Phillips, Jones, Outlaw, Fields, et al., 2011; Huebner, et al., 2004).

Efforts to conceal sexual orientation to avoid such discrimination and victimization may delay the development of a positive self-concept and increase psychological distress among sexual minority male youth (Hetrick & Martin, 1987; Bos, et al. 2008). Stress resulting from concealment of one’s sexual orientation during adolescence may result from constant monitoring of behavior and limiting one’s friendship networks and interests, resulting in isolation among sexual minority youth (Hetrick & Martin, 1987). Concealment has been reported to mediate the relationship between stigma and depression among adult gay men (Frost, Parsons, Nanin, 2007), as well as demonstrate significant associations with depression among sexual minority youth (Frost & Bastone, 2008). Measurement of concealment has typically been aligned with disclosure and “outness” among adult sexual minority persons, and to our knowledge attempts to measure concealment stress among sexual minority youth have not been reported in the literature.

From a developmental perspective, internalized homophobia has been conceptualized as a “failure” of the coming-out process for gay men and lesbians (Meyer & Dean, 1998; Shidlo, 1994), and has demonstrated an inverse relationship to positive identity development in sexual minority youth (Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Braun, 2006). Sexual minority youth grappling with low self-esteem and internalized homophobia often also experience heightened levels of depression and anxiety (Bos et al. 2008; Igartua et al. 2003). Meta-analysis of selected studies of mental health in gay men and lesbians has shown that internalized homophobia correlates more strongly with depression than anxiety (Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010). Longitudinal research has shown that resolution of internalized homophobia over time is associated with positive health outcomes among adult gay men (Herrick, et al., 2013).

Positive identity development as resilience

Emerging research has increasingly focused on resilience as a protective factor for health and well-being among sexual minority populations (Herek & Garnets, 2007; Herrick et al., 2011; Lim et al., 2010), including sexual minority male youth (Bauermeister, 2014; Harper, Brodsky, & Bruce, 2012; Mustanski, Newcomb, & Garofalo, 2011; Savin-Williams, 2006). At present, however, the mechanisms by which sexual minority youth may develop resilience while experiencing adversity associated with minority stress are not well understood. While many theorists and researchers have agreed that resilience constitutes a process, and not an outcome in and of itself, its measurement has proven elusive. Resilience is a construct that has been defined in various ways across multiple disciplines. When applied to adolescents it has been broadly conceptualized in the psychology and public health literature as “a dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity” (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000, p. 543), “a process of or capacity for, or the outcome of successful adaption despite challenges and threatening circumstances” (Garmezy & Matson, 1991, p. 159), and “the process of overcoming the negative effects of risk exposure… and avoiding the negative trajectories associated with risks” (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005, p. 399).

Resilience in youth has been understood to be associated with the cumulative effects of multiple risks, assets and resources that may be present. For example, social and environmental influences such as parental support, adult mentoring, and community organizations promoting positive youth development have been proposed as resources that aid the development of resilience in youth, although most of the intervention research on resilience in adolescents has focused on family-centered approaches, with fewer interventions aimed at school or broader community-based programming (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005). Previous studies of social support and mental health among sexual minority youth have reported mixed findings, with earlier studies employing general or unidimensional measures of social support failing to find direct or moderating effects (Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995). More recent research that has distinguished among sources of social support have found higher degrees of support from sexual minority friends associated with decreased emotional distress among sexual minority youth (Doty, Willoughby, Lindahl, & Malik, 2010). Levels of internalized homophobia have been shown to be attenuated by higher levels of social support from family and friends (Sheets & Mohr, 2009).

Our previous research conducted with sexual minority male youth has proposed a transactional model of same-sex sexual orientation identity development, in which these youth’s identity development occurs through social interactions and transactions within families, schools, communities, and wider environments, including interactions with other sexual minority persons (Harper, et al., 2010). During initial awareness of an emergent sexual orientation, male youth may experience various degrees of isolation, marginalization, and concealment depending on messages received from their ecologic influences. Subsequent to the initial awareness, youth may seek out interactions with other sexual minority persons in various settings. Across these social interactions, sexual minority youth may move through recursive cycles of identity development as they cognitively evaluate and re-evaluate the fit of their emergent identity with messages received from social interactions with others. Although the model presents temporal ordering of evaluating social responses to one’s same-sex attraction, exploration of same-sex identity development through interactions with other sexual minority persons, and subsequent re-evaluation of identity “fit,” these may occur in a cyclical fashion and do not necessarily result in one definitive moment where sexual orientation identity is fully achieved. Instead these processes may occur and change over time, with new experiences and changes in proximal and distal influences. Such a framework is beneficial for studying resilience, in that it allows for identifying possible protective factors associated with positive identity development at multiple levels.

In this study we conceptualized dimensions of minority stress (i.e., experience of sexual orientation stigma, concealment stress during late childhood or adolescence, and current internalized homophobia), as potential risks for major depressive symptoms among male sexual minority youth. Positive identity development was conceptualized as a factor indicative of resilience in the face of such risks and a potential mediator of minority stressors’ effects of major depression. We developed and tested new measures for concealment stress as well as positive identity development. Upon validation of the new measures, we entered them into a path model with minority stress variables and social support to measure effects on major depressive symptomatology. The theoretical model was developed with the following temporally-defined measures and hypotheses: (1) experience of sexual orientation stigma and concealment stress during late childhood/adolescence would be positively associated with current internalized homophobia and major depressive symptomology during the past 7 days, and negatively associated with current social support, (2) positive identity development after meeting other LGBT persons would mediate the paths from past experience of sexual orientation stigma and concealment stress to current internalized homophobia and social support, and (3) current internalized homophobia and current social support would mediate the paths from past experience of sexual orientation stigma and concealment stress to major depressive symptomology during the past 7 days.

METHODS

Participant Characteristics

The data examined in this study were drawn from a study examining associations among identity development, minority stress, and a range of behavioral health indicators within a diverse urban sample of 200 sexual minority male youth ages 16–24 living in Chicago (38% Black/African American, 26.5% Latino/Hispanic, 23.5% White/Caucasian, 12% Multiracial or Other Racial/Ethnic Group). Sixty-two percent of the sample identified as gay, 28.5% identified as bisexual, and smaller percentages identified as “queer,” “down-low,” “trade,” or “other” (summarized for purposes of analysis as “Other”). The mean age of participants was 20.9 years (SD=2.09). A large majority of the sample reported completing at least a high school diploma or GED equivalent, but over half of the sample reported being unemployed. Key participant characteristics are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Participant Characteristics (N=200)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Black/African American | 76 | 38.0 |

| Latino/Hispanic | 53 | 26.5 |

| White/Caucasian | 47 | 23.5 |

| Asian American | 4 | 2.0 |

| Native American/Alaskan Native | 2 | 1.0 |

| Multi-Racial/Bi-Racial/Other | 18 | 9.0 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Gay | 124 | 62.0 |

| Bisexual | 57 | 28.5 |

| Other | 19 | 9.5 |

| Education Level | ||

| Less than high school diploma | 28 | 14.0 |

| High school diploma/GED | 84 | 42.0 |

| Some college/Tech school | 62 | 31.0 |

| College graduate or higher | 26 | 13.0 |

| Employment | ||

| Full-time | 25 | 12.5 |

| Part-time | 52 | 26.0 |

| Unemployed | 123 | 61.5 |

| Depressive Symptoms | ||

| Depression | 95 | 47.5 |

| Major Depression | 64 | 32.0 |

| M | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 20.88 | 2.09 |

| Experience of Sexual Orientation Stigma (4-pt scale) | 1.15 | 0.83 |

| Internalized Homophobia (4-pt scale) | 1.94 | 0.78 |

| Social Support from Family (4-pt scale) | 2.68 | 0.96 |

| Social Support from Friends (4-pt scale) | 3.29 | 0.77 |

| Social Support from Significant Other/Special Person (4-pt scale) | 2.69 | 1.04 |

| Positive Identity Development (4-pt scale) | 3.39 | 0.46 |

| Concealment Stress (4-pt scale) | 2.29 | 0.73 |

Study Procedures

We recruited the sample using a variety of recruitment methods including online advertisements on social networking sites (Facebook), flyers distributed at community venues, and peer recruitment. Peer recruitment resulted in the majority of participants (69%) with social networking site ads and flyers contributing smaller percentages (13.5% and 17.5 %, respectively). Eligibility criteria limited participants to the ages 16–24, being born a biological male, having oral or anal sex with another male during the past 12 months.

As the population of interest for this study was sexual minority male youth, the institutional review board of the lead investigator’s institution granted a waiver of parental consent to participate in the study for participants under the age of 18. This was done to avoid the selection biases present in recruiting only youth whose parents are both aware of and comfortable with their sexual orientation, as well as to protect the confidentiality of youth whose parents may not be aware of their sexual orientation. Once consent (from participants over 18 years old and older) and assent (from participants younger than 18) was received, participants were assigned a confidential study ID that contained no identifying person information and completed an audio computer-assisted study interview (ACASI) survey that lasted approximately one hour. Participants were a paid cash incentive of $40 each for completing the survey. The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the home institution of the primary investigator.

Scale Development

We developed scales for concealment stress and positive identity development from qualitative data gathered from young gay and bisexual males in two previous NIH-funded multi-site studies (ATN020 and ATN070) from which the transactional model of same-sex sexual orientation identity development emerged. In developing these indicators, we retained the language used by the male youth in those studies in order to derive meaningful indicators from the voices and perspectives of this population. We made a conscious decision to utilize the word “gay” or “LGBT” in specific items as they corresponded to specific narratives related by the participants in the previous qualitative studies. As a result, some of the items included the word “gay” when narrative examples pertained to interactions or attitudes regarding gay men, and others, when referencing broader groups of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender persons, include the descriptor “LGBT.”

Concealment stress was assessed using a four-point frequency scale (“never,” “rarely, “some of the time,” “most of the time”), with higher scores indicating greater concealment of sexual orientation during adolescence. Examples of items included in the concealment stress scale are “When you were growing up and realizing you were attracted to other guys sexually, how often did you feel like you couldn’t be yourself?” and “When you were growing up and realizing you were attracted to other guys sexually, how often did you feel like you had to hide your attraction to other guys?” Positive identity development was assessed with items using a four-point agreement scale (“strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “agree,” “strongly agree”), with high scores indicating greater positive identity development. Each item in the positive identity development scale was preceded with the following stem: “How did you think about the following issues after you began meeting other LGBT persons?” Examples of items included in the positive identity development scale are “I got to know people who had similar experiences to me” and “I felt more comfortable about who I was.”

To empirically determine the items that best fit the latent constructs of concealment and positive identity development, we conducted exploratory principal axis factor (PAF) analysis on the positive identity development scale and concealment stress scale. Items with factor loadings greater than .50 were included within a factor (Kim & Mueller, 1978). The 6 items included in the final SM-PID scale loaded on a single factor comprising 46.73% of the total variance. The 8 items included in the final concealment stress scale loaded on a single factor comprising 52.70% of the total variance. The inter-item correlations among each scale’s items within each factor were all acceptable (r>.30). As both scales’ items loaded on single factors, the solution for each was not rotated. The final factor matrix for the positive identity development scale appears as Table 1, and final factor matrix for the concealment stress scale appears as Table 2. Internal consistency of the positive identity development and concealment stress scales was measured using Cronbach’s alpha (α=.76 and α=.87, respectively) and indicated adequate reliability fro group comparisons.

Table 1.

Sexual Minority-related Positive Identity Development Factor Matrix

| Item Stem: “How did you think about the following issues after you began meeting other LGBT persons:” | Factor |

|---|---|

| I felt more comfortable with who I was | .585 |

| I thought there were people I could talk to about my experiences. | .677 |

| I wanted to disprove stereotypes about gay men. | .518 |

| My friends told me that being gay was acceptable. | .598 |

| I got to know people who had similar experiences to me. | .615 |

| I got to know people who were supportive of me. | .662 |

| Eigenvalue | 2.80 |

| % of Variance | 46.73% |

Table 2.

Concealment Stress during Late Childhood/Adolescence Factor Matrix

| Item Stem: “When you were growing up and realizing you were attracted to other guys sexually…” | Factor |

|---|---|

| How often did you feel like you had to hide your attraction to other guys? | .713 |

| How often did you feel like you couldn’t be yourself? | .744 |

| How often did you feel uncomfortable in your own body? | .667 |

| How often did you feel isolated? | .686 |

| How often did you think you could not act on your feelings? | .701 |

| How often did you question yourself based on what other people said about you? | .559 |

| How often did you fear judgment from your family about your feelings toward other men? | .686 |

| How often did you fear judgment from friends about your feelings toward other men. | .659 |

| Eigenvalue | 4.22 |

| % of Variance | 52.70% |

Other Measures

Social Support

Social support was measured using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet & Farley, 1988). We analyzed social support utilizing the three sub-scales assessing social support from family, friends, or a significant other. Each sub-scale consisted of four items and was adapted to a four-point scale (1=strongly disagree, 4=strongly agree). The measure has previously demonstrated strong internal consistency among the family, friends, and significant other sub-scales (α=.87, α=.85, α=.91, respectively); and demonstrated similar levels of internal consistency in our sample (α=.87, α =.85, α=.91, respectively).

Experience of Sexual Orientation Stigma

Experience of sexual orientation stigma was measured using the summed score of an 8-item scale adapted from previously validated measures (Bruce, et al., 2008; Diaz, et al., 2001). Responses used four categories assessing frequency (1=never, 4=many times). Examples of items on the scale include, “While growing up, how often were you made fun of or called names (faggot, queer, sissy, etc.) by your own family, because of the way you behaved?” and “How often has a friend rejected you because of your sexual orientation?” and “How often has your family ignored or refused to acknowledge your sexual orientation?” Internal consistency of the scale was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α=.93).

Internalized Homophobia

Internalized homophobia (or internalization of sexual orientation stigma) was measured using the summed score of a 9-item scale adapted from previously validated measure (Bruce, et al., 2008; Diaz, et al., 2001; Wagner, 1998). Responses used four categories assessing agreement (1=strongly disagree, 4=strongly agree). Examples of items on the scale include, “I have tried to stop being attracted to men” and “If there were a pill to make me straight I would take it” and “Sometimes I feel ashamed of my sexual orientation.” Internal consistency of the scale was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α=.87).

Major Depressive Symptoms

We utilized the Center for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), a 20-item measure that has been used widely to assess depressive symptomology in ethnically diverse groups of adolescents (see Perreira, Deeb-Sossa, Mullan, & Bollen, 2005; Prescott, McArdle, Hishinuma, Johnson, Miyamoto, et al., 1998; Radloff, 1991). We used the conventional cutoff for major depressive symptoms (≥21; Radloff, 1991). The measure demonstrated good internal consistency in our sample (α=.83).

Path Analysis

For the path analysis, we calculated a summed score of the final concealment stress and positive identity development scales, as well as summed scores for the experience of sexual orientation stigma, internalized homophobia, and social support measures. We utilized MPlus software to test exploratory path models that best predicted paths from minority stress processes, positive identity development, current social support, to major depression. Internalized homophobia, positive identity development, current social support and major depression were modeled as endogenous variables and regressed on exogenous variables of experience of sexual orientation stigma and concealment stress. Direct paths were specified between experience of sexual orientation stigma and concealment stress to all endogenous variables. Positive identity development was modeled as a potential mediator of the paths from concealment stress and experience of sexual orientation stigma during adolescence to current internalized homophobia and social support. Sexual orientation identity (gay or bisexual) and race/ethnicity (Black/African American, Latino/Hispanic, White/Caucasian) were modeled as covariates of the exogenous variables in order to examine potential variance in minority stress among these groups. Robust maximum likelihood methods (MLR) were utilized to define a final model through iterative testing of paths and assessment of fit indices using Aikake’s Information Criterion (AIC) and Schwarz’s Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC).

RESULTS

Data Analysis

Of the 200 participants in the study, 6 who completed less than 70% of the positive identity development or concealment stress scale items were excluded from the data analysis, leaving a final sample size of 194 for our various analyses. The exclusion of these 6 participants did not affect the proportions of the three major ethnic groups (Black/African American, Latino/Hispanic, White/Caucasian) or two major sexual identity groups (gay, bisexual) in the sample.

Path Analysis

We tested iterations of the model to include all significant paths, while optimizing fit indices. Preliminary models failed to produce any significant associations between any of the three racial/ethnic groups or two sexual orientation groups with the exogenous variables in the model. Additionally, social support from family and social support from significant other did not produce any significant paths from or to other variables in the model. Successive models were tested until all paths between variables attained statistical significance. Successive iterations resulted in a final model that demonstrated significant paths from experience of sexual orientation stigma to internalized homophobia (β=.138, p<.05) and to major depressive symptoms (β=1.076, OR=2.933, p<.001), and from internalized homophobia to major depressive symptoms (β=.773, OR=2.167, p<.001), with internalized homophobia partially mediating the direct effect of experience of sexual orientation stigma on major depression. Significant paths were also found from concealment stress to positive identity development (β=−.178, p<.05) and to internalized homophobia (β=.418, p<.001), and a significant negative path from positive identity development to internalized homophobia (β=−.527, p<.001), with positive identity development partially mediating the direct effect of concealment stress on internalized homophobia. Further, concealment stress demonstrated a direct significant effect on major depression (β=1.400, OR=4.056, p<.001), and direct significant paths led to social support from friends form experience of sexual orientation stigma (β=−.248, p<.001), and positive identity development (β=.317, p<.001).

Our final path model demonstrated adequate fit using MLR for logistic outcomes (AIC=1299.46, BIC=1354.75), as well as when tested using conventional maximum likelihood (ML) for linear models (RMSEA=.001 and CFI=.998). Although our analyses found a good fit for the data, we tested whether another model could fit the data just as well or better (MacCallum, Wegener, Uchino, & Fabrigar, 1993; MacCallum & Browne, 1993). Theoretically, it is just as plausible that individuals with greater depressive symptoms are more likely to recall their sexual identity development during adolescence more negatively. However, when we performed reverse order modeling and compared both models using fit coefficients, we found our proposed model’s theoretical rationale fit the data better. Figure 1 depicts the final model with significant paths, and Table 4 shows the estimated coefficients and odds ratios associated with the paths in the final model.

Figure 1.

Final Path Model

Table 4.

Final Path Model Stats

| β | S.E. | Z | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Depressive Symptoms on | ||||||

| Internalized Homophobia | 0.773 | .252 | 3.063 | 2.167 | (1.431, 3.283) | .002 |

| Concealment Stress | 1.400 | .392 | 3.575 | 4.056 | (2.130, 7.725) | <.001 |

| Experience of Sexual Orientation Stigma | 1.076 | .255 | 4.216 | 2.933 | (1.928, 4.464) | <.001 |

| Social Support from Friends on | ||||||

| Positive Identity Development | 0.317 | .090 | 3.526 | -- | -- | <.001 |

| Experience of Sexual Orientation Stigma | −0.248 | .062 | −4.025 | -- | -- | <.001 |

| Internalized Homophobia on | ||||||

| Positive Identity Development | −0.527 | .084 | −6.306 | -- | -- | <.001 |

| Concealment Stress | 0.418 | .070 | 5.960 | -- | -- | <.001 |

| Experience of Sexual Orientation Stigma | 0.138 | .061 | 2.246 | -- | -- | .025 |

| Positive Identity Development on | ||||||

| Concealment Stress | 0.155 | .056 | 2.798 | -- | -- | .005 |

| Social Support from Friends with | ||||||

| Internalized Homophobia | −0.101 | .034 | −2.944 | -- | -- | .003 |

DISCUSSION

We offer an exploratory model that empirically identifies significant paths between minority stress dimensions, positive identity development, social support, and major depressive symptoms. As hypothesized, experience of sexual orientation stigma and concealment stress during adolescence demonstrated significant effects on major depressive symptoms, as well as significant effects on current internalized homophobia. Also, as hypothesized, internalized homophobia partially mediated the path from experience of sexual orientation stigma on major depressive symptoms, and positive identity development partially mediated the path from concealment stress to internalized homophobia. These results align with previous research on minority stress, identity development, and depression among sexual minority male youth (Almeida, et al., 2009; Frost & Bastone, 2008; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010; Rosario, et al., 2006).

An unexpected finding is the positive association of concealment stress during late chilodhood/adolescence on positive identity development, as we hypothesized that this path would produce a negative association. This result suggests that some sexual minority male youth who experienced greater past isolation and self-monitoring are more likely to report positive identity development that resulted from meeting other LGBT persons. This development of a positive sexual orientation identity was in turn negatively associated with internalized homophobia. Taken together, these findings suggest that for some participants the transactions that constituted their initial meetings with other LGBT persons may have served as resources in the development of a positive identity and resilience even after prior concealment of sexual orientation. Conversely, youth who may not have experienced these positive interactions, or had limited access to these resources, were more likely to experience internalized homophobia, both due to the effects of past experience of sexual orientation stigma and concealment stress. This unexpected finding may also be a function of our sample characteristics, and the possibility of bias as a result of our non-probability based sampling methods.

Our positive identity measure examined development at multiple ecological levels, including internal (“I felt more comfortable with who I was,” “I feel that I am closer to the person I want to be”), dyadic (“My friends told me that being gay was acceptable,” “I got to know people who had similar experiences to me”), and societal (“I wanted to disprove stereotypes about gay men”). The connection with a with a larger LGB community during the identity development process is supported by the work of Fassinger and Miller (1996) who have stressed the importance of differentiating between the development of an individual sexual orientation identity and the development of a group membership identity which involves developing affiliations with other members of the LGB community. Youth who have not developed a group membership identity are typically less far along in their sexual orientation identity development process since they may have accepted their own sexual orientation, but have not been comfortable enough to connect with other LGB people (Fassinger & Miller, 1996). Thus, a lack of connection with other members of the larger LGB community may restrict youth from resources that could aid in the development of a positive identity and serve as a resilience resource when faced with marginalization and discrimination they may have experienced in other settings (Harper, Fernandez, Bruce, Hosek, Jacobs, & ATN, 2013; Rosario et al., 2001; Waldo, McFarland, Katz, MacDellar, & Valleroy, 2000; Wexler, et al., 2009).

Our findings suggest that concealment of one’s sexual orientation during late childhood or adolescence interacts and align with other minority stress dimensions among sexual minority male youth, and contribute to our understanding of minority stress processes among youth and young adults by focusing on a particular time (“When you were growing up and realizing you were attracted to other guys sexually…”). This approach is distinctive from much of the previous minority stress research that has emphasized assessment of concealment within workplace contexts among adults (DiPlacidio, 1998; Meyer, 2007; Waldo, 1999). Future studies of health and well-being among sexual minority male youth and young adults may benefit from further testing of our concealment stress and positive identity development measures on larger, population-based samples.

The significant and positive association with current social support from friends indicates that positive identity development as a transactional process may most often manifest itself in the development and maintenance of friendships with other LGBT persons and supportive friendships from non-LGBT persons. Social support from family members was not characterized by significant associations with the other variables in the model. Although previous resilience researchers have emphasized the role of parental support in the development of resilience in the face of adversity (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005), for young gay male youth friendship networks may play as significant if not larger role than that of the biological family. The direct significant negative path from past experience of sexual orientation stigma and current social support from friends that is not mediated by positive identity development emphasizes the deleterious effects of this minority stressor on social support resources for some sexual minority male youth.

Implications of Findings

The findings of this study have potential practice implications for the development and delivery of interventions focused on improving the mental health and well-being of sexual minority male youth. The associations revealed in the path model suggest the strong positive influence of interacting with other LGB people and receiving social support from friends, as such positive interactions serve to buffer the negative effects of experiencing and internalizing sexual orientation stigma—both of which are associated with higher levels of major depressive symptoms. Thus future interventions may work to increase positive and health-promoting interactions with LGB people and communities, and to help young people build social support networks with friends who affirm their sexual orientation. Prior studies have demonstrated that both the development of a positive individual gay/bisexual identity and the development of supportive connections within the larger gay community have been associated with health protective benefits for sexual minority male youth, particularly in terms of sexual health (Harper, et al., 2013; Rosario et al., 2001; Waldo, et al., 2000).

The role of close friends is critical during this developmental period, and for sexual minority male youth it may be even more important due to the lack of parental support sometimes experiences by sexual minority youth (Jadwin-Cakmak, Pingel, Harper, & Bauermeister, 2014; Ryan, et al., 2009). Given the association between social support from friends and positive identity development, future interventions may explore the feasibility and acceptability of incorporating the friends of sexual minority male youth in both preventive and therapeutic interventions.

Enhancing critical consciousness among youth has been identified as an avenue for promoting physical and mental health by assisting young people with understanding and challenging negative social influences such as sexism, racism, and other social injustices that can lead to poor self-concept and low self-esteem (Campbell & MacPhail, 2002; Diemer et al., 2006; Wallerstein & Bernstein, 1988; Watts, Abdul-Adil, & Pratt, 2002; White, 2007). Critically reflecting on and resolving sources of internalized homophobia has also been demonstrated by sexual minority male youth, by identifying contradiction and hypocrisies in the sources of and transmission of stigma-based messages (Kubicek, McDavitt, Carpineto, Weiss, Iverson, & Kipke, 2009). Recent recommendations for cognitive-behavioral treatment approaches addressing minority stress among adult gay and bisexual men could be adapted for sexual minority male youth (Pachankis, 2014).

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

While our findings are subject to several limitations present within the study, we employed a developmental approach to our measures so that we could examine the concealment stress during adolescence and positive identity development. For both of these constructs of interest, for example, participants were asked to think and answer the items based on when they were growing up or beginning to meet other LGBT people. This temporally-defined measurement approach allows us to make stronger inferences regarding the temporal order between our constructs of interest and major depressive symptoms. Furthermore, our findings echo results of prior studies – further supporting our study’s internal and statistical conclusion validity. Nonetheless, use of these measures in future research with will help further confirm their validity in studies with this population.

Though casual statements must be tempered by our cross-sectional design, the comparison between our model and the alternate (reversed) path model suggest that our hypothesized pathways were both theoretically and statistically more favorable than the alternate causal route. Nevertheless, we recognize the importance of measuring these constructs over time in order to understand the dynamic changes in sexual minority youth’s identity development in order to ensure that recall bias was not present in our study. Future longitudinal research exploring the prospective changes in the relationships observed between the study variables across adolescence and young adulthood are warranted. Finally, the generalization of our findings to larger populations of sexual minority male youth is limited by the non-probability-based sampling methods employed in the study. Further, we relied solely on self-reported data, but we believe that the use of an ACASI to gather data may have lessened the inclination of participants to underreport levels of stigma and depressive symptoms.

Finally, the significant associations among positive identity development, concealment stress, and internalized homophobia point to the role of positive identity development as a process of resilience in the presence of minority stressors during adolescence and young adulthood among sexual minority male youth. Positive identity development did not demonstrate significant associations with the other minority stressor in the model (experience of sexual orientation stigma) or major depressive symptomology, suggesting that there are additional components of resilience besides positive identity development that merit investigating among this population. Additional resources and assets that contribute to resilience need to be investigated to further our understanding how resilience develops in sexual minority youth exposed to multiple dimensions of minority stress. Longitudinal research is needed in order to more precisely estimate how dimensions of minority stress, identity development, social support, mental health, and resilience interact at different stages of adolescence and young adulthood. Although sexual orientation did not demonstrate significant associations with minority stress dimensions in our study, future studies that develop multiple models for gay and bisexual male youth may help delineate differential resilience and identity development processes for these groups.

This study helps further our understanding of minority stress, identity development, and the process of resilience among sexual minority male youth. Our findings suggest that there may be distinct interpersonal and intrapersonal pathways associated with minority stress dimensions, socialization and developmental outcomes among this population. Further research is needed to explore additional assets and resources characteristic of these youth’s resilience in the presence of multiple stressors during their adolescence and youth adulthood.

Acknowledgments

Support for this study was provided by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health under grant K01 MH 089838. Our deep gratitude goes to our research participants whose thoughtful input made this study possible.

References

- Allport GW. The Nature of Prejudice. New York: Doubleday; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida J, Johnson RM, Corliss HL, Molnar BE, Azrael D. Emotional distress among LGBT youth: The influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:1001–1014. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA. How statewide LGB policies from “under our skin” to “into our hearts”: Fatherhood aspirations and psychological well-being among emerging adult sexual minority men. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2014;43(8):1925–1305. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0059-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Meanley S, Hickok A, Pingel E, Loveluck J, Van Hemert W. Sexuality-related work discrimination and its association with the health of gay and bisexual emerging and young adults in the Detroit Metro Area. Sexuality Research & Social Policy. 2014;11(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s13178-013-0139-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos HMW, Sandfort TGM, Bruyn EH, Hakvoort EM. Same-Sex attraction, social relationships, psychosocial functioning, and school performance in early adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(1):59–68. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks VR. Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce D, Ramirez-Valles J, Campbell R. Stigmatization, substance use, and sexual risk behavior among Latino gay and bisexual men and transgender persons. Journal of Drug Issues. 2008;38(1):235–260. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce D, Harper GW the ATN. Operating without a safety net: Gay male adolescents’ responses to marginalization and migration and implications for theory of syndemic production of health disparities. Health Education and Behavior. 2011;38(4):367–378. doi: 10.1177/1090198110375911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, MacPhail C. Peer education, gender and the development of critical consciousness: Participatory HIV prevention by South African youth. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55:331–345. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker TR, Austin SB, Schuster MA. The health and health care of lesbian, gay and bisexual adolescents. Annual Review of Public Health. 2010;31:457–477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in community settings: Personal challenges and mental health problems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21(4):421–448. doi: 10.1007/BF00942151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from 3 U.S. cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(6):927–932. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diemer MA, Kauffman A, Koenig N, Trahan E, Hsieh CA. Challenging Racism, Sexism, and Social Injustice: Support for Urban Adolescents’ Critical Consciousness Development. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;12(3):444–460. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.3.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFulvio G. Sexual minority youth, social connection and resilience: From personal struggle to collective identity. Social Science and Medicine. 2011;72:1611–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPlacidio J. Minority stress among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: a consequence of heterosexism, homophobia, and stigmatization. In: Herek GM, editor. Stigma and sexual orientation: understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Vol. 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Doty ND, Willoughby BLB, Lindahl KM, Malik NM. Sexuality related social support among Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:1134–1147. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassinger RE, Miller BA. Validation of an inclusive model of sexual minority identity formation on a sample of gay men. Journal of Homosexuality. 1996;32(2):53–78. doi: 10.1300/j082v32n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S, Zimmerman M. Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Parsons JT, Nanin JE. Stigma, concealment and symptoms of depression as explanations of sexually transmitted infections among gay men. Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12(4):636–640. doi: 10.1177/1359105307078170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Bastone LM. The role of stigma concealment in the high school experiences of gay, Lesbian and bisexual individuals. LGBT Youth. 2008;5(1):26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N, Masten AS. The protective role of competence indicators in children at risk. In: Cummings EM, Greene AL, Karraker KH, editors. Life-span developmental psychology: Perspectives on stress and coping. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Harper GW. Not all adolescents are the same: Addressing the unique needs of gay and bisexual male youth. Adolescent Medicine. 2003;14(3):595–611. doi: 10.1016/S1041349903500470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee J. Psycholinguistics and Literacies: Ideology in Discourse. London: Falmer Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of a Spoiled Identity. New York: Prentice-Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Gwadz MV, Clatts MC, Yi H, Leonard NR, Goldsamt L, Lankenau S. Resilience among young men who have sex with men in New York City. Sexuality Research & Social Policy. 2006;3(1):13–21. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2006.3.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Bruce D, Serrano P, Jamil OB. The role of the internet in the sexual identity development of gay and bisexual male adolescents. In: Hammack PL, Cohler BJ, editors. The Story of Sexual Identity: Life Course and Sexual Identity Narrative Perspectives on Gay and Lesbian Identity. New York: Oxford U; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Fernández MI, Jamil OB, Hidalgo MA, Torres RS, Bruce D the ATN. Empirically based transactional model of same-sex sexual orientation identity development. Presented at American Psychological Association; San Diego, CA.. 2010. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Brodsky A, Bruce D. What’s good about being gay? Perspectives from youth. Journal of LGBT Youth. 2012;9:22–41. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2012.628230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Fernández MI, Bruce D, Hosek SG, Jacobs RJ the ATN . The role of multiple identities in engagement in care among gay/bisexual male adolescents living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(1):213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0071-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):896–903. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Garnets LD. Sexual orientation and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:353–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick AL, Lim SH, Wei C, Smith H, Guadamuz T, Friedman MS, Stall R. Resilience as an untapped resource in behavioral intervention design for gay men. AIDS & Behavior. 2011;15(1S):S25–29. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9895-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick AL, Stall R, Chmiel JS, Guadamuz TE, Penniman T, Shoptaw S, et al. It gets better: Resolution of internalized homophobia over time and associations with positive health outcomes among MSM. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(4):1423–1430. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0392-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger SL, D’Augelli AR. The impact of victimization on the mental health and luicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31(1):65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hetrick ES, Martin AD. Developmental issues and their resolution for gay and Lesbian adolescents. Journal of Homosexuality. 1987;14(1–2):25–43. doi: 10.1300/J082v14n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightow-Weidman LB, Phillips G, Jones KC, Outlaw AY, Fields SD, et al. Racial and sexual identity-related maltreatment among minority YMSM: Prevalence, perceptions, and the association with emotional distress. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2011;25(S1):S39–S45. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM. Experiences of harassment, discrimination, and physical violence among young gay and bisexual men. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(7):1200–1203. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguarta KJ, Gill K, Montoro R. Internalized homophobia: A factor in depression, anxiety, and suicide in the gay and lesbian population. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 2003;22(2):15–30. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2003-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadwin-Cakmak L, Pingel E, Harper GW, Bauermeister JA. Coming out to dad: Young gay and bisexual men’s experiences disclosing same-sex attraction to their fathers. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1557988314539993. published online July 1, 2014 1557988314539993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamil OB, Harper GW, Fernandez MI. Sexual and ethnic identity development among gay/bisexual/questioning (GBQ) male ethnic minority adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15(3):203–214. doi: 10.1037/a0014795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JO, Mueller CW. Introduction to Factor Analysis: What it is and how to do it. Sage University Press; London: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek K, McDavitt B, Carpineto J, Weiss G, Iverson EF, Kipke MD. “God made me gay for a reason”: young men who have sex with men’s resiliency in resolving internalized homophobia from religious sources. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2009;24:601–633. doi: 10.1177/0743558409341078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek K, McNeeley M, Holloway IW, Weiss G, Kipke MD. “It’s like our own little world”: Resilience as a factor in participating in the ballroom community subculture. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(4):1524–1539. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0205-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SH, Ostrow D, Stall R, Chmiel J, Herrick A, Shoptaw S, Kao U, Carrico A, Plankey M. Changes in stimulant drug use over time in the MACS: Evidence for resilience against stimulant drug use among men who have sex with men. AIDS & Behavior. 2012;16(1):151–158. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9866-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71(3):543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Wegener DT, Uchino BN, Fabrigar LR. The problem of equivalent models in applications of covariance structure analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:185–199. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW. The use of causal indicators in covariance structure models: Some practical issues. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:533–541. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ, Fields EL, Bryant LO, Harper SR. Masculine socialization and sexual risk behaviors among Black men who have sex with men: A qualitative exploration. Men & Masculinities. 2009;12(1):90–112. [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Development and validation of ego identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1966;3:551–558. doi: 10.1037/h0023281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, King KM, Miles J, Gold MA, et al. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: A meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction. 2008;103:546–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays V, Cochran S. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(11):1869–1876. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice and discrimination as social stressors. In: Meyer IH, Northridge ME, editors. The Health of Sexual Minorities. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 242–267. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Dean L. Internalized homophobia, intimacy, and sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men. In: Herek GM, editor. Stigma and sexual orientation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 160–186. [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, Stall R. Greater risk for HIV infection of Black men who have sex with men: a critical literature review. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(6):1007–1019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Newcomb ME, Garafalo R. Mental health of lesbian, gay and bisexual youths: A developmental resiliency perspective. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2011;23(2):204–225. doi: 10.1080/10538720.2011.561474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(8):1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE. Uncovering clinical principles and techniques to address minority stress, mental health, and related health risks among gay and bisexual men. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice. 2014;21(4):313–330. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreira KM, Deeb-Sossa N, Harris KM, Bollen K. What are we measuring? An evaluation of the CES-D across race/ethnicity and immigrant generation. Social Forces. 83(4):1567–1601. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA, McArdle JJ, Hishinuma ES, Johnson RC, Miyamoto RH, Andrade NN, et al. Prediction of major depression and dysthymia from CES-D scores among ethnic minority adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37(5):495–503. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199805000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20(2):149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Hunter J, Maguen S, Gwadz M, Smith R. The coming-out process and its adaptational and health-related associations among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Stipulation and exploration of a model. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:133–160. doi: 10.1023/A:1005205630978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Ethnic/racial differences in the coming-out process of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: A comparison of sexual identity development over time. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10(3):215–228. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Braun L. Sexual orientation identity development among lesbian, gay and bisexual youths: Consistency and change over time. Journal of Sex Research. 2006;43:46–58. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST. Queer in America: Citizenship for sexual minority youth. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6(4):258–263. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST. Beyond risk: Resilience in the lives of sexual minority youth. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues in Education. 2005;2(3):5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Futterman D. Lesbian and Gay Youth. New York: Columbia University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc E. Research on adolescent sexual orientation: Development, health disparities, stigma, and resilience. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(1):256–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00727.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-William RC. The New Gay Teenager. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Rodriguez RG. A developmental, clinical perspective on Lesbian, gay male, and bisexual youths. In: Gullotta TP, Adams GR, Montemayor R, editors. Adolescent Sexuality. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Sheets R, Jr, Mohr J. Perceived social support from friends and family and psychosocial functioning in bisexual young adult college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56(1):152–163. [Google Scholar]

- Shidlo A. Internalized homophobia: Conceptual and empirical Issues in measurement. In: Greene B, Herek Gregory M, editors. Lesbian and Gay Psychology: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 176–205. [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Friedman M, Catania JA. Interacting epidemics and gay men’s health: A theory of syndemic production among urban gay men. In: Wolitski RJ, Stall R, Valdiserri RO, editors. Unequal opportunity: Health disparities affecting gay and bisexual men in the United States. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 251–274. [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Paul JP, Greenwood G, Pollack LM, Bein E, Crosby GM, et al. Alcohol use, drug use and alcohol-related problems among men who have sex with men: The Urban Men’s Health Study. Addiction. 2001;96:1589–1601. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961115896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner G. Internalized homophobia scale. In: Davis CM, Yarber WL, Bauserman R, Schreer GE, Davis S, editors. Handbook of sexuality-related measures. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. p. 371.72. [Google Scholar]

- Waldo CR. Working in a majority context: a structural model of heterosexism as minority stress in the workplace. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46:218–2323. [Google Scholar]

- Waldo CR, McFarland W, Katz MH, MacDellar D, Valleroy LA. Very young gay and bisexual men are at risk for HIV infection: The San Francisco Young Men’s Survey II. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2000;24(2):168–74. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200006010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Empowerment education: Freire’s ideas adapted to health education. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15:379–304. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts RJ, Abdul-Adil J, Pratt T. Sociopolitical and civic development in young African-American men: A Psycho Educational Approach. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2002;3(1):41–50. [Google Scholar]

- White J. Working in the midst of ideological and cultural differences: Critically reflecting on youth suicide prevention in indigenous communities. Canadian Journal of Counseling. 2007;41:213–227. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg MS, Williams CJ, Pryor DW. Bisexuals at midlife: Commitment, salience, identity. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 2001;30(2):180–208. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler LM, DiFluvio G, Burke TK. Resilience and marginalized youth: Making a case for personal and collective meaning-making as part of resilience research in public health. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69:565–570. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BDM, Miller RL. Strategies for managing heterosexism used among African American gay and bisexual men. Journal of Black Psychology. 2002;28:371–391. [Google Scholar]

- Wong CF, Weiss G, Ayala G, Kipke MD. Harassment, discrimination, violence, and illicit drug use among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2010;22(4):286–298. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.4.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of social support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]