Abstract

Background

Inflammation is involved in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Hypertensive animals have an increased number of perivascular macrophages in cerebral arteries. Macrophages might be involved in remodeling of the cerebral vasculature. We hypothesized that peripheral macrophage depletion would improve middle cerebral artery (MCA) structure and function in hypertensive rats.

Methods

for macrophage depletion, six-week-old stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRSP) were treated with liposome-encapsulated clodronate (CLOD, 10ml/kg/every 3 or 4 days, I.P.), or vehicle (PBS lipo). MCA structure and function were analyzed by pressure and wire myography.

Results

blood pressure was not affected by CLOD. The number of perivascular CD163 positive cells per microscopic field was reduced in the brain of SHRSP+CLOD. CLOD treatment caused an improvement in endothelium-dependent dilation after intralumenal perfusion of ADP and incubation with acetylcholine (Ach). Inhibition of nitric oxide production blunted the Ach response, and endothelium-independent dilation was not altered. At an intralumenal pressure of 80 mmHg, MCA from SHRSP+CLOD showed increased lumen diameter, decreased wall thickness and wall-to-lumen ratio. Cross-sectional area of pial arterioles from SHRSP+CLOD was higher than PBS lipo.

Conclusion

These results suggest that macrophage depletion attenuates MCA remodeling and improves MCA endothelial function in SHRSP.

Keywords: hypertension, vascular remodeling, endothelium-dependent vasodilation, liposome-encapsulated clodronate, middle cerebral artery

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension leads to structural changes in the resistance vasculature through the process of vascular remodeling. Remodeling encompasses changes in the vessel wall that reduce the lumen diameter and increase the wall thickness and wall-to-lumen ratio (29) of hypertensive vessels when compared to vessels of normotensive subjects (1, 14). These changes might impact regional blood flow regulation and lead to increased risk of end-organ damage (19). In the cerebral circulation, the MCA is an important component of blood flow regulation (16) because cerebral vascular resistance is carried equally between large arteries, like the MCA, and arterioles (13). Remodeling impairs the MCA’s ability to control blood flow by auto-regulation, leading to distal capillary destabilization and organ damage (41). In addition, it impairs vasodilation (18), which can reduce collateral blood flow following obstruction of an artery. Thus remodeling of the cerebral vasculature might increase the risk of stroke, and the damage caused by cerebral ischemia (18). Although increased wall stress during hypertension is important to trigger remodeling, studies show that vascular remodeling can be prevented or reversed without reducing blood pressure (23, 35, 37, 38), suggesting that perivascular mechanisms might be important modulators of this process. However, the mechanisms underlying hypertensive MCA remodeling are not completely understood.

Essential hypertension is linked with systemic inflammation in humans (33) and rats (6). Macrophage infiltration is increased in the aorta, mesenteric and intramyocardial arteries (36) and cerebral microvessels (31) of SHRSP when compared to normotensive WKY rats. In the periphery, mice deficient in m-CSF show reduced remodeling of mesenteric arteries (9, 22). However, in these studies vascular inflammation was considered a consequence of prolonged exposure to vasoactive agents and not a causative agent of vascular remodeling. Once in the vessel wall, macrophages can release molecules capable of altering the structure and function of blood vessels, thus potentially playing an active role in remodeling of the cerebral vasculature. Therefore, we hypothesized that perivascular macrophages contribute to remodeling of the cerebral and peripheral vasculature in SHRSP. We tested this hypothesis by removing circulating macrophages using CLOD. The MCA was used to study the cerebral vasculature, and third-order branches of the mesenteric arterial arcade, MRA, were used to study the peripheral vasculature.

METHODS

Animals and treatments

Six week-old male SHRSP from the colony housed at Michigan State University were randomized into two groups. To remove peripheral macrophages, rats were treated with CLOD. Clodronate was a gift of Roche Diagnostics GmbH and was incorporated into liposomes as described elsewhere (46). Rats were injected with CLOD (10ml/kg) every 3 or 4 days for 6 weeks, the first dose was administered via tail vein; i.p. injections were used thereafter. This treatment regimen causes a prolonged peripheral macrophage depletion (12). Control rats received PBS lipo (placebo). Rats were treated with CLOD from week 6 to week 12 of age because this is the period during which the blood pressure in SHRSP increases exponentially (8). We have previously shown that treatments during this period are efficacious in attenuating vascular remodeling (34, 35, 38). Rats used for the collection of perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) from mesenteric arteries were treated as described above with the exception that the treatment was only maintained for two weeks. Rats were maintained on a 12:12hr light:dark cycle, with tap water and regular chow ad libitum. At 12 weeks of age, rats were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane and euthanized by decapitation after collection of arterial blood from the abdominal aorta. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee and was in accordance with the American Physiological Society’s “Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals.”

Measurement of blood pressure

Blood pressure was measured by tail-cuff using a RTBP1001 tail-cuff blood pressure system (Kent Scientific, Torrington CT) as described previously (34).

Flow cytometry

Quantification of circulating and peritoneal phagocytic cells in PBS lipo and CLOD-treated SHRSP was performed using FCM. Blood was collected from the abdominal aorta in heparinized tubes, and the total number of blood leukocytes was quantified using a Z1 Coulter Particle Counter (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Aliquots containing 1×106 cells were incubated for 5 min with ACK buffer (in grams/liter: NH4Cl 8.024, KHCO3 1.001, EDTA 0.0037) at room temperature for red blood cells lysis. Cells were then washed with FCM buffer (Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution with 1% Bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.1% sodium azide) three times and incubated with Fc block (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for 20 min on ice. Cells were then incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-CD11b and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD163 (ABD Serotec, Oxford, UK) for 20 min on ice. Non-specific staining was assessed by first blocking Fc receptors in all cells with an anti-Fc receptor antibody on unstained cells. Cells were washed in FCM buffer twice and fixed with BD Cytofix (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), washed twice with FCM buffer and 50,000 events were collected using the BD FACSCanto II coupled to the FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo 8.8.6 (Treestar Software, Ashland, OR). Gating was set using the Fc-blocked non-stained cells. Cells obtained by peritoneal lavage were processed using the same protocol described above.

Immunofluorescence

Cryosections of the brain (10µm thick) from perfusion-fixed rats were used for IF identification of CD163 (a macrophage marker) and α-SMA. Rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital, the thoracic cavity was exposed and 0.9% NaCl solution (saline) with heparin (1000UI/mL) and papaverin (10−5 mol/L) was injected into the left ventricle of the heart to wash the blood and dilate the vasculature. A puncture in the right atria allowed the blood+saline to be washed out. The perfusion pressure was maintained at 80mmHg and 250ml of saline flushed the rat. After, 250 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde was perfused. The brain was then removed and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 hours, washed in PBS and placed in 20% sucrose-PBS for cryosectioning. Sections were incubated overnight with primary antibodies against CD163 (ABD Serotec, Oxford, UK) and α-SMA (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and then incubated with fluorescent-tagged secondary antibodies. Sections were then mounted in ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Images were acquired using an Axioskop 40 (Carl Zeiss Inc., Mexico) coupled to a camera (AxioCam MRc5, Carl Zeiss Inc.) and the number of perivascular CD163 positive cells in 6 microscopic fields was counted using the AxioVision Rel. 4.6 software. Sections without the primary antibody were negative controls. An investigator blinded to the experimental groups performed the cell counting. Data are expressed as number of perivascular CD163 positive cells per microscopic field.

Morphometry of Pial Arterioles

Histological sections of the brain (10µm thick) from perfusion-fixed rats were stained with hematoxilin-eosin for morphometrical analysis of pial arterioles. Images were acquired as described above. Cross-sectional area of pial arterioles was measured using a calibrated AxioVision Rel. 4.6 software by an investigator blinded to the experimental groups. Only the intima and medial layers of arterioles were included in the cross-sectional area measurement. A total of 5 arterioles per animal were measured, and the data was averaged per animal. Data are expressed as mean cross-sectional area.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

mRNA was extracted from cerebral cortex and PVAT using an RNeasy® Lipid Tissue kit (QIAGEN), from CBV using TRIZOL reagent. mRNA was reverse-transcribed (Superscript® VILO™, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and qRT-PCR was performed using Taqman® probes in a 7500 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystem). Fold changes from control were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method (25). CBV mRNA was normalized to 2-β microglobulin mRNA expression; RP132 was used for cerebral cortex and PVAT mRNA.

Pressure Myography

MCA structure was assessed by pressure myography (Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark) as described previously (35). MCA contractility to 5-HT (10−10–10−5 mol/L) and endothelium-dependent dilation to intralumenal perfusion of ADP (10−9 to 10−5 mol/L) were assessed. MCA’s equilibrated in oxygenated physiological salt solution (PSS, in mmol: 141.9 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.12 KH2PO4, 1.7 MgSO4′7H2O, 2.8 CaCl2, 10 Hepes, 5 Dextrose, 0.5 EDTA, pH 7.4) until development of spontaneous myogenic tone, which was calculated using the following formula: %tone = [1-(active lumen diameter/passive lumen diameter)] × 100. MCA’s passive structure was assessed with calcium-free PSS containing 2mmol/L EGTA plus 10−5 mol/L of SNP and intralumenal pressure was increased from 3 to 180mmHg in 20mmHg increments. The wall-to-lumen ratio, circumferential wall stress and wall strain were calculated (3). Passive distensibility was calculated as described previously (5). The elastic modulus (β-coefficient) was calculated from the stress/strain curves using an exponential model (y=aeβx) where β is the slope of the curve: the higher the β-coefficient the stiffer the vessel.

Wire Myography

MCA endothelial function was further assessed using a wire myograph (Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark). MCAs were isolated and cleaned, and 2mm rings were mounted into the wire myograph using 40µm-thick stainless steel wires. MCAs were allowed to equilibrate for 30 min in oxygenated PSS at 37°C without tension, which was then increased to 2mN in 0.5mN increments with a 10 minutes equilibration period. After stabilization at 2mN, rings viability was assessed by exposing them to 10−6 mol/L 5-HT, and endothelium integrity was assessed by 10−6 mol/L Ach. Rings were washed and pre-constricted with 10−6 mol/L 5-HT to build concentration-response curves for Ach (10−10 to 3×10−5 mol/L) ± the eNOS inhibitor L-NAME, 10−5 mol/L, and the NO donor SNP (10−10 to 3×10−5 mol/L). Rings were washed and constricted with 100mmol/L KCl to analyze agonist-independent constriction. Data are expressed as percent of KCl constriction.

Mesenteric resistance artery structure

Third-order branches from the mesenteric vascular bed were isolated and stored on ice-cold PSS for mounting in the pressure myograph after completion of the MCA experiment. Passive structure was assessed as described above with the exception that the intralumenal pressure was increased in 30mmHg increments.

Statistical Analysis

Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Blood pressure, body and organ weights, IF, morphometry, FCM, qRT-PCR and spontaneous tone generation data were analyzed by Student’s t-Test. MCA structure, contractility and endothelium-dependent dilation were analyzed by Two-Way ANOVA, with a Bonferroni post-test. A p value of 0.05 or lower was considered significant. Concentration-response curves to 5-HT, ADP, Ach ± L-NAME and SNP were further analyzed by non-linear regression (curve-fit) to calculate log EC50 and changes in pharmacological parameters using the Prism Software (GraphPad, version 5.0a).

RESULTS

Physiological parameters and blood pressure

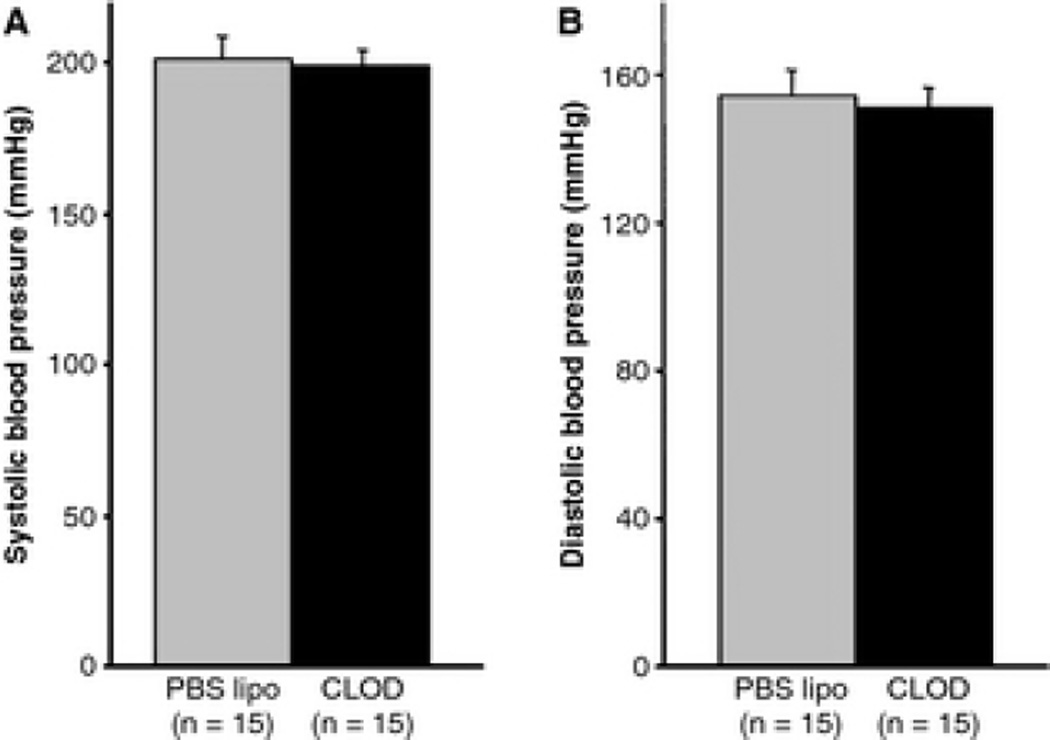

There was no difference in body weights (253±4 vs. 247±4g, PBS lipo vs. CLOD), heart/body weight ratio (0.49±0.02 vs. 0.47±0.02, PBS lipo vs. CLOD) and kidney/body weight ratio (1.01±0.01 vs. 1.03±0.03, PBS lipo vs. CLOD). CLOD treatment caused the expected reduction in spleen/body weight ratio (0.22±0.01 vs. 0.14±0.01, PBS lipo vs. CLOD, p<0.05). Systolic (202±7 vs. 200±5mmHg, PBS lipo vs. CLOD) and diastolic (154±7 vs. 152±5mmHg, PBS lipo vs. CLOD) arterial pressures were not affected by CLOD treatment (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Blood pressure from 12-week-old SHRSP treated with CLOD or PBS lipo measured by tail-cuff. There was no difference in systolic and diastolic blood pressure in SHRSP after treatment with CLOD when compared to PBS lipo-treated SHRSP. Data are means ± SEM of a total of 75 cycles per rat performed in three different days (25 cycles per day).

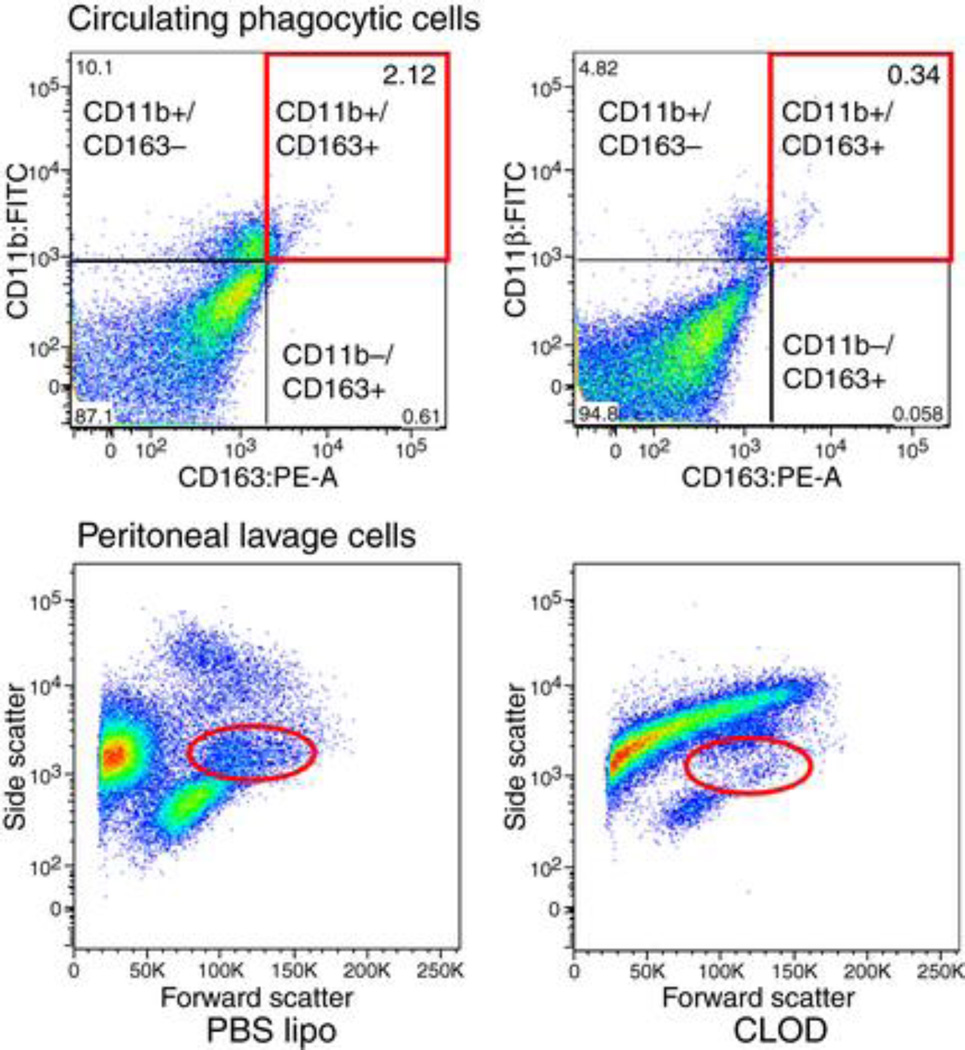

CLOD-treated SHRSP had less circulating and peritoneal macrophages

Peripheral macrophage depletion was assessed by FCM. The number of circulating macrophages double-positive for CD11b and CD163 was reduced in CLOD-treated rats (0.28±0.03 vs 1.19±0.34% total cells, CLOD (n=3) vs SHRSP (n=4), p=0.04). Similarly, the number of macrophages in the peritoneal lavage was reduced in SHRSP+CLOD (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Representative FCM analysis for quantification of macrophages in SHRSP treated with PBS lipo or CLOD. Upper panels represent the analysis of circulating phagocytic cells in blood that are double-positive for CD11b and CD163. Note that the number of events is higher in SHRSP-treated with PBS lipo (upper left panel) than SHRSP-treated with CLOD (upper right panel). The number of macrophages in the peritoneal cavity was also quantified by FCM (lower panels). Cell populations were separated by side-scatter and forward-scatter. Note that the number of events is smaller in CLOD-treated SHRSP (lower right panel) than PBS lipo-treated SHRSP (lower left panel).

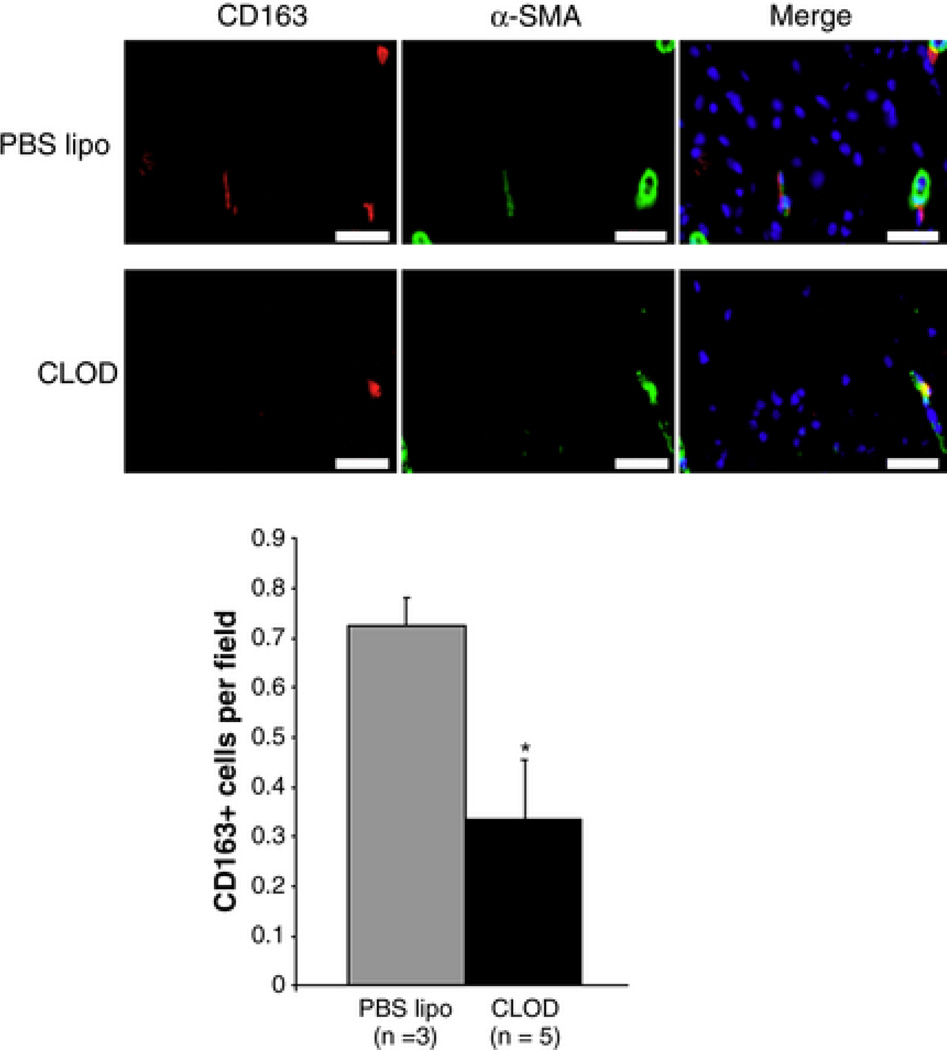

CLOD treatment reduced the number of perivascular CD163 positive cells in the cerebral cortex

To validate that depletion of circulating phagocytes would result in reduction of perivascular phagocytes in the brain, the number of perivascular CD163 positive cells in the cerebral cortex of SHRSP was assessed by IF. CLOD treatment reduced the number of perivascular CD163 positive cells per microscopic field in the cerebral cortex of SHRSP, when compared to SHRSP treated with PBS lipo (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescent (IF) staining of perivascular macrophages in the cerebral vasculature of SHRSP. Macrophages were identified as cells with immunoreactivity to CD163 (red), and only CD163-positive cells surrounding blood vessels (identified by immunoreactivity for α-SMA, green) were counted. Nuclei were identified by DAPI-staining (blue). Upper panels are representative images from SHRSP treated with PBS lipo, and lower panels are images from CLOD-treated SHRSP. Bar graph: quantification of the IF. CLOD caused a significant reduction in perivascular CD163 positive cells in SHRSP. *p < 0.05, Student's t-test.

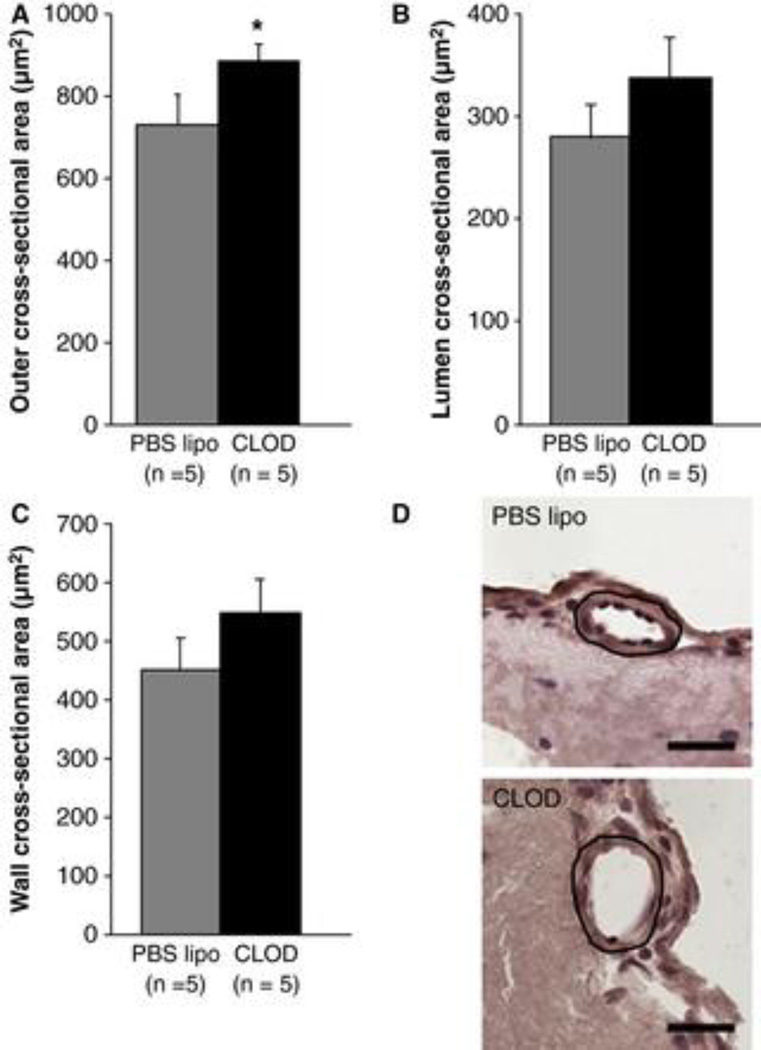

Cross-sectional area of pial arterioles was increased in CLOD-treated SHRSP

Morphometric analysis of pial arterioles showed that CLOD treatment increased their cross-sectional area when compared to SHRSP treated with PBS lipo (Fig 4A, p=0.05). A small, although not significant, increase in lumen (Fig 4B, p=0.14) and wall cross-sectional were also observed (4C, p=0.12).

Figure 4.

Morphometric analyses of pial arterioles. CLOD treatment caused a significant increase in the cross-sectional area of pial arterioles in SHRSP (A), when compared to SHRSP treated with PBS lipo. There was a small, although not-significant, increase in the lumen (B, p = 0.14) and wall (C, p = 0.12) cross-sectional areas after six weeks of CLOD treatment. (D) Representative images of pial arterioles from PBS lipo (left) and CLOD (right)-treated SHRSP. The circled area represents the cross-sectional area of the arteriole. Bar = 25 µm. Morphometric measurements were performed in 10 µm-thick slices of the brain from perfusion-fixed rats. Images were acquired using a 40× objective and cross-sectional area measurements performed using a calibrated software by an investigator blinded to the experimental groups. Data are means ± SEM. *p = 0.05, Student's t-test.

CLOD treatment reduced CD68 and TNF-α mRNA expression in the cerebral cortex and CBV

CLOD treatment reduced CD68 mRNA expression in the cerebral cortex (1.06±0.12 vs. 0.78±0.10, PBS lipo vs. CLOD, p<0.05), but not in CBV (1.00±0.03 vs. 1.06±0.10, PBS lipo vs. CLOD). In addition, TNF-α mRNA expression was reduced in the cerebral cortex (1.04±0.10 vs. 0.76±0.07, PBS lipo vs. CLOD, p=0.02) and CBV (1.02±0.09 vs. 0.82±0.05, PBS lipo vs. CLOD, p=0.03).

CLOD did not alter MCA’s contractility, myogenic tone and myogenic reactivity

Peripheral phagocyte depletion did not change the MCA’s spontaneous myogenic tone (Table 1) and the response to the contractile agent 5-HT (Fig 5).

Table 1.

Passive vessel structure and MCA spontaneous myogenic tone after 6 weeks of CLOD treatment.

| PBS lipo (n=12) | MCA† CLOD (n=10) |

WKY rats (n=4)Ψ | PBS lipo (n=5) | MRA‡ CLOD (n=5) |

WKY rats (n=4)Ψ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumen diameter (µm) | 230±9 | 254±4* | 286±8 | 245±7 | 215±7 | 280±21 |

| Outer Diameter (µm) | 278±9 | 294±5 | 314±11 | 294±7 | 298±6 | 311±20 |

| Wall Thickness (µm) | 24±1 | 20±1* | 14±1 | 24±0.8 | 24±0.9 | 16±1.4 |

| Wall-to-lumen ratio | 0.11±0.008 | 0.08±0.006* | 0.05±0.004 | 0.10±0.005 | 0.09±0.005 | 0.06±0.007 |

| Lumen CSA (µm2) | 42059±3162 | 50930±1729 | 64398±3556 | 47300±2837 | 49729±2643 | 62316±8843 |

| Vessel CSA (µm2) | 61496±3933 | 67864±2185 | 77452±5011 | 67935±3433 | 69975±2812 | 76675±9850 |

| Wall CSA (µm2) | 19437±1199 | 16934±1162 | 13054±1607 | 20636±866 | 20246±722 | 14386±1543 |

| Vessel Strain | 0.41±0.06 | 0.36±0.03 | 0.45±0.03 | 0.77±0.03 | 0.83±0.04 | 0.74±0.03 |

| Vessel Stress | 398±28 | 543±39* | 854±74 | 454±21 | 486±28 | 831±90 |

| β-coefficient | 7.03±0.9 | 7.63±0.4 | 8.61±0.6 | 3.83±0.08 | 3.74±0.08 | 6.23±1.02 |

| % tone generation | 34.9±4.1 | 39.7±6.8 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

Values are mean±SEM.

values at an intralumenal pressure of 80mmHg;

Values at an intralumenal pressure of 90mmHg;

values previously published (34);

Significantly different from PBS lipo (p<0.05); n/a: non-applicable.

Figure 5.

CLOD treatment did not alter MCA reactivity to the constricting agent 5-HT. The ability of the MCA to respond to agonist-induced constriction was assessed by adding increasing concentrations of 5-HT in the tissue bath. CLOD treatment did not change the concentration-response curve to 5-HT, as seen by percent of maximum response (A), or the change in lumen diameter from baseline (B). The MCA was maintained in warm (37°C), oxygenated PSS at an intralumenal pressure of 80 mmHg and was allowed to equilibrate for 10 minutes before a measurement was taken and the next dose of 5-HT was added. Data are means ± SEM.

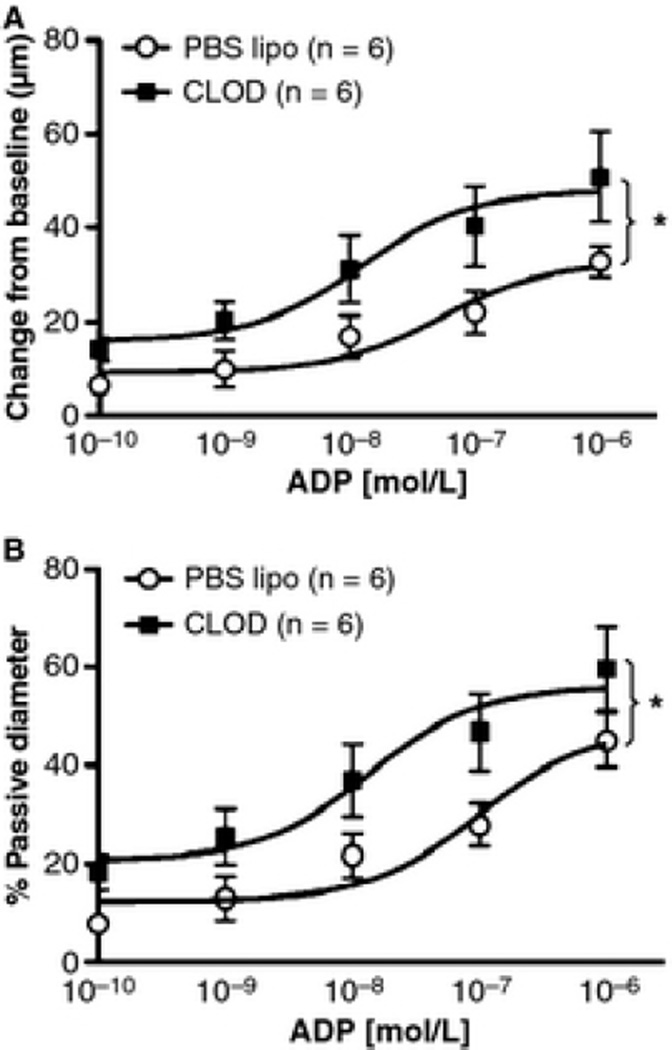

CLOD treatment improved MCA’s endothelium-dependent dilation

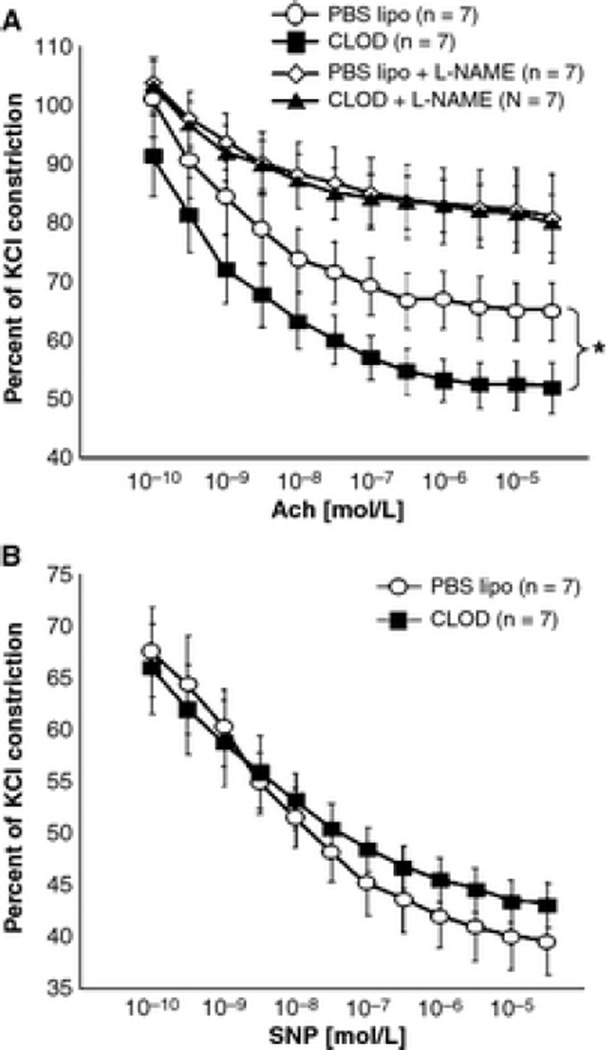

Peripheral phagocyte depletion improved endothelium-dependent dilation of the MCA to intralumenal perfusion of ADP (Fig 6). CLOD treatment caused an up and leftward shift in the concentration-response curve of ADP and increased the maximal dilation of the MCA to this agent. However, the logEC50 was not changed by the treatment (−7.02±0.29 vs. −6.54±0.27 mol/L, PBS lipo vs. CLOD). The improvement in endothelium function was further confirmed by incubating MCA rings with Ach in the wire myograph, with or without L-NAME. MCA rings from CLOD-treated SHRSP showed an improvement in Ach-mediated dilation that disappeared after incubation with L-NAME (Fig 7A). Endothelium-independent dilation to SNP was not different between treatments (Fig 7B). This improvement in Ach dilation was not a consequence of reduced contractility to 5-HT (% KCl constriction: 114±4 vs 111±4, PBS lipo vs CLOD). Despite the improvement in maximum dilation to Ach, its logEC50 was not altered (−9.61±0.18 vs −9.47±0.16 mol/L, PBS lipo vs CLOD).

Figure 6.

CLOD treatment improved endothelium-dependent dilation of the MCA to ADP. CLOD treatment increased both the raw dilation of the MCA, observed as a change in diameter from baseline (A), and the percent of passive diameter (B). *p < 0.01, two-way ANOVA. Values are means ± SEM. The MCA was mounted in a pressure myograph and kept in oxygenated warm PSS under 80 mmHg of intralumenal pressure and physiological flow. ADP was added to the intralumenal perfusate.

Figure 7.

CLOD treatment improved MCA dilation to Ach. MCA rings (2 mm) were mounted on a wire myograph and pre-constricted with 10–6 mol/L 5-hydroxytriptamine (5-HT, % KCl constriction: 114 ± 4 vs. 111 ± 4, PBS lipo vs. CLOD). Concentration-response curves to Ach in absence or presence of the NOS inhibitor l-NAME were constructed. MCA relaxation to Ach was improved in SHRSP after CLOD treatment, and this effect was blunted by pre-incubation of MCA rings with l-NAME (10–5 mol/L, A). MCA response to the endothelium-independent vasodilator SNP was not different between groups (B). *p < 0.05, PBS lipo vs. CLOD, two-way ANOVA. Values are means ± SEM.

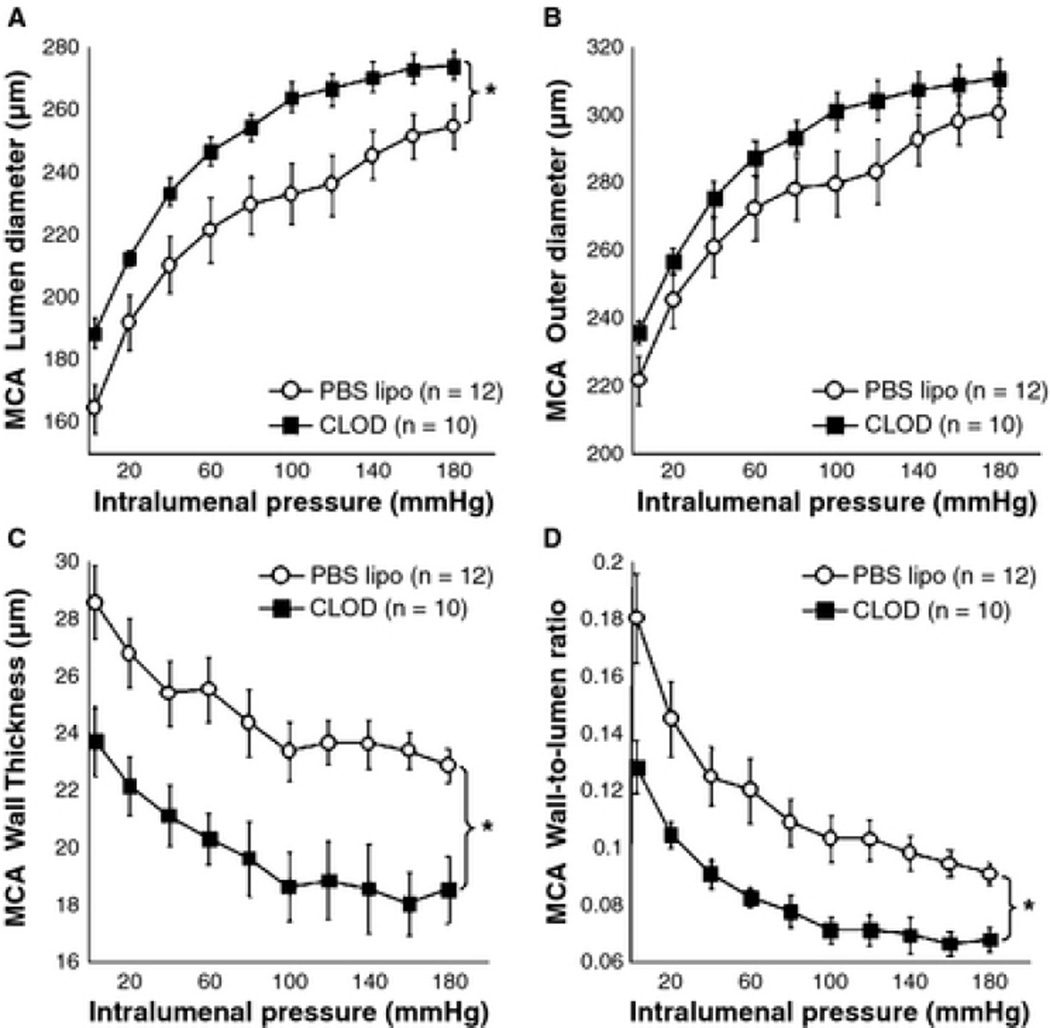

CLOD treatment improved MCA passive structure

Peripheral macrophage depletion caused an 11% increase in the MCA lumen diameter (Fig 8A). The lumen cross-sectional area (CSA) was increased (Table 1), without changing the outer diameter (Fig 8B) and vessel CSA. Wall thickness (Fig 8C), wall CSA (Table 1) and the wall-to-lumen ratio (Fig 8D) were decreased after CLOD treatment. Vessel stress was increased, without changing strain, stiffness and distensibility. No differences were found in the β-coefficient (Table 1). Importantly, PBS lipo had no effect on MCA structure in SHRSP when compared to untreated SHRSP (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Peripheral phagocyte depletion improved MCA passive structure in SHRSP. CLOD treatment increased the lumen diameter (A), decreased the wall thickness (C) and wall-to-lumen ratio (D), without changing outer diameter (B). *p < 0.05, PBS lipo vs. CLOD, two-way ANOVA. Values are means ± SEM. The MCA was mounted in a pressure myograph and kept in oxygenated warm calcium-free PSS supplemented with 2 mM EGTA and 10 µM under no-flow conditions.

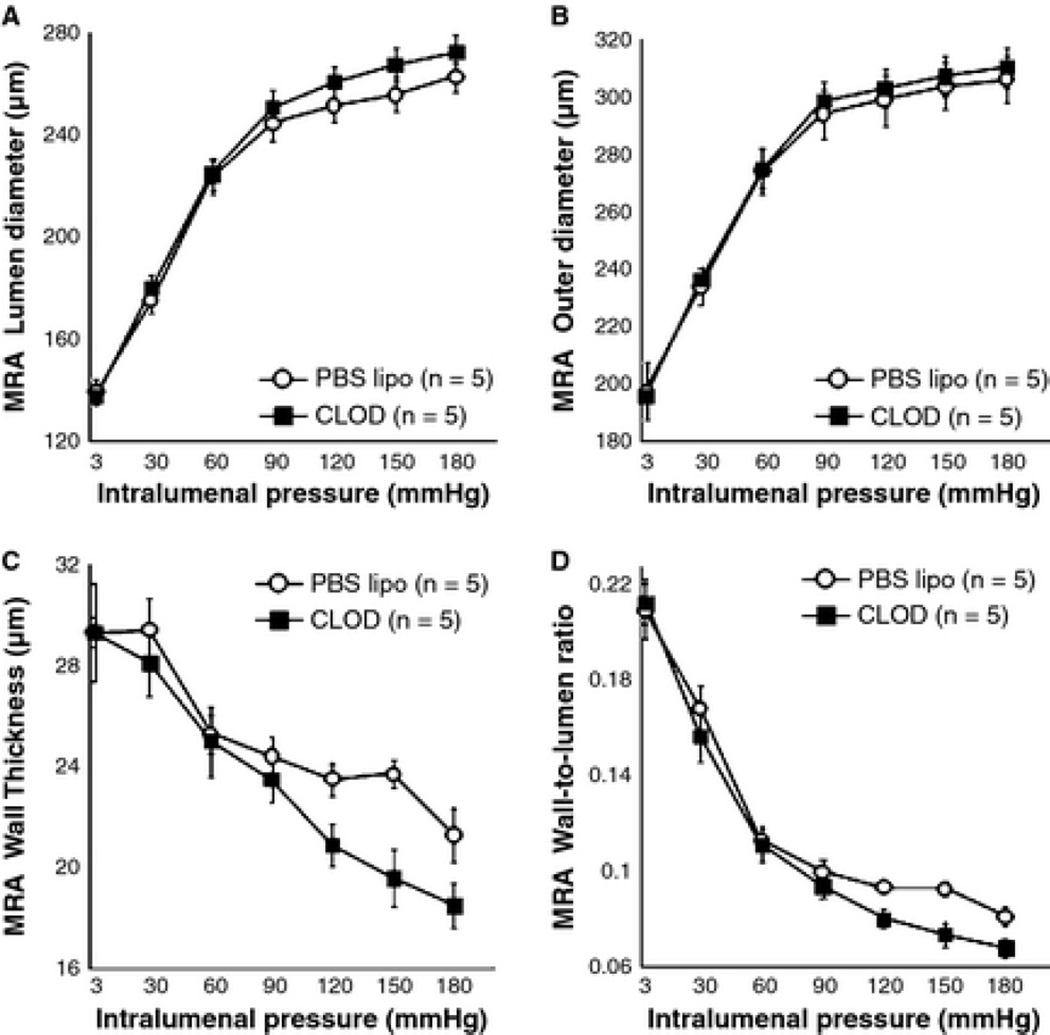

CLOD treatment did not alter MRA structure

Peripheral phagocyte depletion did not prevent MRA remodeling in SHRSP (Fig 9A–D and Table 1).

Figure 9.

Peripheral phagocyte depletion did not improve MRA passive structure in SHRSP (p > 0.05, PBS vs. CLOD, ANOVA). CLOD treatment did not change lumen (A) and outer (B) diameters. There was a small, but insignificant, reduction in the wall thickness (C) and wall-to-lumen ratio (D) at higher intralumenal pressures. Values are means ± SEM. The MRA was mounted in a pressure myograph and kept in oxygenated warm calcium-free PSS supplemented with 2 mM EGTA and 10 µM of sodium nitroprusside and under no-flow conditions.

CLOD treatment for 2 weeks reduced CD163 and TNF-α in the MRA PVAT

In order to test the hypothesis that macrophage depletion leads to an upregulation in proinflammatory cytokine production by PVAT, we treated SHRSP with CLOD or PBS lipo for 2 weeks and measured mRNA expression of TNF-α and CD163 by qRT-PCR. Our data shows that this treatment regimen reduced mRNA expression of CD163 in PVAT (Fig 10A) and caused a trend towards a 2-fold increase in TNF-α mRNA (Fig 10B).

Figure 10.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α production by PVAT. Two-weeks treatment of SHRSP with CLOD resulted in decreased expression of CD163 mRNA (A), suggesting reduction in macrophage number. In addition, this treatment regimen caused a trend towards an increase in TNF-α mRNA expression in the MRA PVAT (B), suggesting that, in the absence of macrophages, white adipose tissue can produce proinflammatory cytokines that mediate MRA hypertensive remodeling. Data are means ± SEM. *p = 0.01, Student's t-test; Ψp = 0.056, Student's t-test.

DISCUSSION

The novel findings in this study are that peripheral macrophage depletion improves MCA endothelial function and passive structure in SHRSP. An increase in the cross-sectional area of pial arterioles was also observed, suggesting that perivascular macrophages have deleterious effects in the cerebral microcirculation. Interestingly, peripheral and cerebral arteries responded differently to the treatment, suggesting that the mechanisms driving remodeling are different depending on the vascular bed. Importantly, CLOD treatment did not reduce the blood pressure, suggesting the effects of inflammatory cells on the vasculature are blood pressure independent. The increased MCA lumen diameter and endothelium-dependent dilation have the potential to improve cerebral blood flow and prevent, or at least delay the onset of disorders caused by chronic reduction in blood perfusion to the brain, including vascular dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and recovery of ischemic stroke. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing a direct link between hypertensive cerebral vascular remodeling and perivascular macrophages in SHRSP.

The link between hypertension and inflammation is clear. In humans, plasma C-reactive protein levels correlate with the development of hypertension (40) and preactivated circulating monocytes are increased in patients with essential hypertension (10). Inflammatory markers, including interleukin-6, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 are associated with hypertension (4, 26). Increased intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 are potentially important because they could increase monocyte/macrophage adhesion and infiltration in the vessel wall. In the spontaneously hypertensive rat, aortic TNF-α mRNA levels are increased (39). TNF-α is associated with rennin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation (27), and angiotensin receptor blockade reduces aortic TNF-α expression (39). Important for the current study, activation of the rennin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is intrinsically involved in hypertensive MCA remodeling (11, 38).

It is unclear whether inflammation is a cause or consequence of hypertension. In SHRSP blood pressure increases gradually over time (38), and CLOD did not prevent this. The lack of an antihypertensive effect of the treatment could be due to, 1) the complexity of hypertension development in the SHRSP, and 2) that inflammation could be a consequence of the hypertension, and exacerbates end-organ damage. The absence of an antihypertensive effect could also be explained by the observation that CLOD did not increase MRA lumen diameter. The mesenteric bed receives 15–20% of the cardiac output (20), thus contributing markedly to total peripheral resistance and, consequently, blood pressure. We speculate that CLOD most likely did not alter the structure of other vascular beds also involved in the control of blood pressure, including the renal vasculature. SHRSP are known to have increased renal vascular resistance, which is an important factor regulating systemic blood pressure in this model (30). One caveat of the present study is that blood pressure was measured by tail-cuff. We recognize that telemetry would have been more accurate; however, we have shown that the data obtained with the tail-cuff system used here are very similar to those obtained with telemetry in SHRSP (38). Therefore, we feel confident that the treatment does not affect blood pressure.

The mechanism of action for CLOD is that macrophages incorporate the liposomes and disrupt them intracellularly. The size and membrane composition of the liposomes causes them to be internalized exclusively by macrophages (46). Once within the cell, the liposome capsule is digested and clodronate is released. Clodronate is highly polar and does not cross biological membranes, thus accumulating in the cytoplasm to levels that are toxic (44, 45), triggering apoptosis (47). Thus, these cells are eliminated without damaging adjacent non-phagocytic cells. CLOD have not been widely used in cardiovascular research, but one study showed that CLOD prevented flow-dependent outward carotid artery remodeling (32). While this is different from hypertension-induced remodeling, this study highlights the usefulness of CLOD in vascular studies. In our study we confirmed the effectiveness of CLOD in reducing the population of circulating phagocytic cells. In addition, we show that the number of perivascular CD163 positive cells in the cerebral cortex was reduced after CLOD treatment, as well as CD68 mRNA expression. We did not observe alteration in CD68 mRNA levels in CBV. The amount of tissue from CBV is very limited, and it is possible that we are at the limit of resolution for qRT-PCR. TNF-α mRNA is decreased in the cerebral cortex and CBV of CLOD animals. These results suggest that phagocytes might be the primary source of cytokines locally released in the vessel wall. Importantly, CLOD does not cross the blood brain barrier and does not affect microglia (28).

In addition to the structural beneficial effects of CLOD treatment, macrophage depletion caused an improvement in endothelium-dependent dilation to ADP. Phagocytic cells express high levels of NADPH-oxidase, an enzyme involved in production of reactive oxygen species in the vasculature (43). Reactive oxygen species, particularly the superoxide anion, react with NO and generate peroxinitrite. As a consequence, NO-dependent vasodilation becomes impaired in these vessels. ADP and Ach-mediated dilations are, in part, dependent on NO generation in endothelial cells (48). Through the removal of an important source of reactive oxygen species, it is possible that the NO bioavailability in the MCA was increased, thus accounting for the increased vasodilatory response to ADP and Ach. This possibility is further supported by the fact that pre-incubation of MCA rings with L-NAME, an eNOS inhibitor, blunted the vasodilatory response to the same level as SHRSP treated with PBS lipo. In addition, there was no difference in response to the NO donor SNP, suggesting that the improvement in relaxation observed in CLOD SHRSP is most likely due to NO production by endothelial cells, and not in the activity of soluble guanylate cyclase in vascular smooth muscle cells. The possible beneficial physiological consequences of improved vasodilation are at least two-fold: 1) improved basal cerebral blood flow and 2) increased vasodilation of the collateral circulation after blockage of a cerebral artery, thus potentially reducing ischemic damage in the brain of hypertensive subjects.

We found an increase in MCA lumen diameter and decrease in its wall thickness, as well as an increase in the cross-sectional area of pial arterioles after chronic peripheral macrophage depletion. This finding supports our hypothesis that infiltrating phagocytes are causative agents in cerebral vascular remodeling. Once in the vessel wall, these cells have the ability to release many substances that have the potential to alter vascular structure in a paracrine manner, including ROS, proinflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases. We recently showed that superoxide anion is involved in MCA remodeling in SHRSP, and that superoxide scavenging attenuates remodeling in these animals (34). Similarly, we showed that inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases with doxycycline prevents hypertensive MCA remodeling (35). It is possible that by reducing the number of perivascular phagocytes in SHRSP there is a decrease in levels of both these mediators, thus preventing the reduction in lumen diameter of the MCA observed in SHRSP. TNF-α, a major cytokine released by phagocytes, is linked to cerebral vessel weakening and aneurism formation (21), as well as activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2, induction of matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression (2, 15), and, consequently, vascular remodeling. CLOD caused a reduction in TNF-α mRNA expression in CBV and cerebral cortex of SHRSP, suggesting that macrophages might be a major source of TNF-α in the arterial wall. Independently of the mechanism, improvement of the cerebral artery structure after CLOD treatment can have beneficial effects in the ischemic brain. After ischemia/reperfusion injury, the ability of the MCA to generate tone is diminished (7), and the major determinant of blood flow to the ischemic hemisphere after reperfusion is the lumen diameter of the MCA. In addition, improvement of the endothelial function of the arteries located in the Circle of Willis can increase collateral blood supply in case of MCA occlusion, which will be carried to the ischemic hemisphere by anastomoses in the pial arterioles. The increase in cross-sectional of pial arterioles might add to a global increase in collateral perfusion, thus potentially reducing ischemic insult in the brain.

It is important to recognize that in SHRSP the MCA remodeling is partially an adaptive response to protect the downstream parenchymal arterioles from the elevated blood pressure (17). Therefore, one could postulate that reducing MCA wall thickness without reducing blood pressure would increase the risk of hemorrhagic stroke due to the increase in wall stress. The SHRSP in this study were not at risk for hemorrhagic stroke because they did not receive a stroke-prone diet. Although the remodeling was attenuated in this study, the MCA’s wall was still thicker than in normotensive WKY rats. We have recently showed that in WKY rats the MCA wall thickness is 13.8±1.4µm (35), and in the present study the MCA wall thickness from CLOD-treated SHRSP is 19.6±1.4µm. It is possible that this maintenance in wall thickness is sufficient to protect the cerebral microvasculature in the CLOD-treated SHRSP.

Surprisingly, CLOD treatment did not attenuate MRA remodeling. The finding is in disagreement with the study from Ko et al (22) where attenuation of hypertensive MRA remodeling was observed in m-CSF null mice. MRA are surrounded by white adipose tissue, and adipocytes produce proinflammatory cytokines (42). mCSF was also shown to be important for adipocyte hyperplasia (24), thus it is possible that mCSF deficiency attenuates MRA remodeling by reducing adipocyte-induced vascular inflammation. In our study, we hypothesized that, in the absence of macrophages, adipocytes would take on a proinflammatory phenotype and this might function as a “backup” mechanism for cytokine release. In fact, we show that TNF-α mRNA expression is increased in the MRA PVAT after a 2-weeks CLOD treatment, supporting our hypothesis. The increase in TNF-α mRNA was accompanied by a reduction in CD163 mRNA expression, showing that even this shorter CLOD treatment depleted macrophages. Thus, despite the reduced macrophage population in the mesenteric PVAT the inflammatory cytokine load on the vessels appears to be increased, and this may be the cause of the continued remodeling in the MRA.

PERSPECTIVES

In summary, the present study shows that infiltrating macrophages play an active role in endothelial dysfunction and remodeling of cerebral arteries and arterioles in SHRSP. This study adds to our knowledge of the cerebral vascular dysfunction in chronic hypertersion, a major risk factor for cerebrovascular accidents, vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Elucidating the mechanisms of hypertensive remodeling of the cerebral arterial tree might lead to new therapies aimed at improving cerebral perfusion, thus reducing acute ischemic damage and preventing the onset of diseases caused by chronic cerebral hypoperfusion.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Mr. Robert Crawford for the technical help with the flow cytometry analysis.

Support: National Institutes of Health (HL077385 to AMD and DA007908 and DA020402 to NEK) and the American Heart Association (0840122N:AMD and 12PRE8960019:PWP).

Abbreviations

- MCA

middle cerebral artery

- CLOD

liposome-encapsulated clodronate

- PBS lipo

liposome-encapsulated PBS

- WKY

Wistar-Kyoto rats

- SHRSP

stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats

- mCSF

macrophage colony stimulating factor

- MRA

mesenteric resistance arteries

- FCM

flow cytometry

- IF

immunofluorescence

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PSS

physiological saline solution

- α-SMA

α-smooth muscle actin

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- CBV

cerebral arteries (MCA, posterior and anterior communicating, posterior and anterior cerebral, and basilar arteries)

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytriptamine

- SNP

sodium nitroprusside

- Ach

acetylcholine

- L-NAME

N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- NO

nitric oxide

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aalkjaer C, Heagerty AM, Petersen KK, Swales JD, Mulvany MJ. Evidence for increased media thickness, increased neuronal amine uptake, and depressed excitation--contraction coupling in isolated resistance vessels from essential hypertensives. Circ Res. 1987;61:181–186. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arenas IA, Xu Y, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Davidge ST. Angiotensin II-induced MMP-2 release from endothelial cells is mediated by TNF-alpha. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C779–C784. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00398.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumbach GL, Hajdu MA. Mechanics and composition of cerebral arterioles in renal and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1993;21:816–826. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.21.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chae CU, Lee RT, Rifai N, Ridker PM. Blood pressure and inflammation in apparently healthy men. Hypertension. 2001;38:399–403. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.38.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan SL, Chapman AC, Sweet JG, Gokina NI, Cipolla MJ. Effect of PPARgamma inhibition during pregnancy on posterior cerebral artery function and structure. Front Physiol. 2010;1:130. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2010.00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CM, Schachter D. Elevation of plasma immunoglobulin A in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension. 1993;21:731–738. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.21.5.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cipolla MJ, McCall AL, Lessov N, Porter JM. Reperfusion decreases myogenic reactivity and alters middle cerebral artery function after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke. 1997;28:176–180. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson AO, Schork N, Jaques BC, Kelman AW, Sutcliffe RG, Reid JL, Dominiczak AF. Blood pressure in genetically hypertensive rats. Influence of the Y chromosome. Hypertension. 1995;26:452–459. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Ciuceis C, Amiri F, Brassard P, Endemann DH, Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Reduced vascular remodeling, endothelial dysfunction, and oxidative stress in resistance arteries of angiotensin II-infused macrophage colony-stimulating factor-deficient mice: evidence for a role in inflammation in angiotensin-induced vascular injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2106–2113. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000181743.28028.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorffel Y, Latsch C, Stuhlmuller B, Schreiber S, Scholze S, Burmester GR, Scholze J. Preactivated peripheral blood monocytes in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1999;34:113–117. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorrance AM, Rupp NC, Nogueira EF. Mineralocorticoid receptor activation causes cerebral vessel remodeling and exacerbates the damage caused by cerebral ischemia. Hypertension. 2006;47:590–595. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000196945.73586.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ezendam J, Kosterman K, Spijkerboer H, Bleumink R, Hassing I, van Rooijen N, Vos JG, Pieters R. Macrophages are involved in hexachlorobenzene-induced adverse immune effects. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;209:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Regulation of large cerebral arteries and cerebral microvascular pressure. Circ Res. 1990;66:8–17. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feihl F, Liaudet L, Levy BI, Waeber B. Hypertension and microvascular remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;78:274–285. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han YP, Tuan TL, Wu H, Hughes M, Garner WL. TNF-alpha stimulates activation of pro-MMP2 in human skin through NF-(kappa)B mediated induction of MT1-MMP. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:131–139. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harper SL, Bohlen HG, Rubin MJ. Arterial and microvascular contributions to cerebral cortical autoregulation in rats. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:H17–H24. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.246.1.H17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayashi K, Naiki T. Adaptation and remodeling of vascular wall; biomechanical response to hypertension. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials. 2009;2:3–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heistad DD, Mayhan WG, Coyle P, Baumbach GL. Impaired dilatation of cerebral arterioles in chronic hypertension. Blood Vessels. 1990;27:258–262. doi: 10.1159/000158817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Intengan HD, Schiffrin EL. Vascular remodeling in hypertension: roles of apoptosis, inflammation, and fibrosis. Hypertension. 2001;38:581–587. doi: 10.1161/hy09t1.096249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobson ED. Physiology of the mesenteric circulation. Physiologist. 1982;25:439–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jayaraman T, Paget A, Shin YS, Li X, Mayer J, Chaudhry H, Niimi Y, Silane M, Berenstein A. TNF-alpha-mediated inflammation in cerebral aneurysms: a potential link to growth and rupture. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4:805–817. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ko EA, Amiri F, Pandey NR, Javeshghani D, Leibovitz E, Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Resistance artery remodeling in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension is dependent on vascular inflammation: evidence from m-CSF-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1789–H1795. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01118.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumai Y, Ooboshi H, Ago T, Ishikawa E, Takada J, Kamouchi M, Kitazono T, Ibayashi S, Iida M. Protective effects of angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker on cerebral circulation independent of blood pressure. Exp Neurol. 2008;210:441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine JA, Jensen MD, Eberhardt NL, O'Brien T. Adipocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor is a mediator of adipose tissue growth. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1557–1564. doi: 10.1172/JCI2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madej A, Okopien B, Kowalski J, Haberka M, Herman ZS. Plasma concentrations of adhesion molecules and chemokines in patients with essential hypertension. Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57:878–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marchesi C, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in vascular inflammation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Micklus MJ, Greig NH, Tung J, Rapoport SI. Organ distribution of liposomal formulations following intracarotid infusion in rats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1124:7–12. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(92)90118-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulvany MJ. Vascular remodelling of resistance vessels: can we define this? Cardiovasc Res. 1999;41:9–13. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagaoka A, Kakihana M, Suno M, Hamajo K. Renal hemodynamics and sodium excretion in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1981;241:F244–F249. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1981.241.3.F244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura T, Yamamoto E, Kataoka K, Yamashita T, Tokutomi Y, Dong YF, Matsuba S, Ogawa H, Kim-Mitsuyama S. Pioglitazone exerts protective effects against stroke in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats, independently of blood pressure. Stroke. 2007;38:3016–3022. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.486522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nuki Y, Matsumoto MM, Tsang E, Young WL, van Rooijen N, Kurihara C, Hashimoto T. Roles of macrophages in flow-induced outward vascular remodeling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:495–503. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peeters AC, Netea MG, Janssen MC, Kullberg BJ, Van der Meer JW, Thien T. Pro-inflammatory cytokines in patients with essential hypertension. Eur J Clin Invest. 2001;31:31–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pires PW, Deutsch C, McClain JL, Rogers CT, Dorrance AM. Tempol, a superoxide dismutase mimetic, prevents cerebral vessel remodeling in hypertensive rats. Microvasc Res. 2010;80:445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pires PW, Rogers CT, McClain JL, Garver HS, Fink GD, Dorrance AM. Doxycycline, a matrix metalloprotease inhibitor, reduces vascular remodeling and damage after cerebral ischemia in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H87–H97. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01206.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pu Q, Brassard P, Javeshghani DM, Iglarz M, Webb RL, Amiri F, Schiffrin EL. Effects of combined AT1 receptor antagonist/NEP inhibitor on vascular remodeling and cardiac fibrosis in SHRSP. J Hypertens. 2008;26:322–333. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f16aaf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rigsby CS, A E, V PD, DM P, Dorrance AM. Effects of Spironolactone on Cerebral Vessel Structure in Rats With Sustained Hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rigsby CS, Pollock DM, Dorrance AM. Spironolactone improves structure and increases tone in the cerebral vasculature of male spontaneously hypertensive stroke-prone rats. Microvasc Res. 2007;73:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanz-Rosa D, Oubina MP, Cediel E, de Las Heras N, Vegazo O, Jimenez J, Lahera V, Cachofeiro V. Effect of AT1 receptor antagonism on vascular and circulating inflammatory mediators in SHR: role of NF-kappaB/IkappaB system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H111–H115. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01061.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sesso HD, Buring JE, Rifai N, Blake GJ, Gaziano JM, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein and the risk of developing hypertension. Jama. 2003;290:2945–2951. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sonoyama K, Greenstein A, Price A, Khavandi K, Heagerty T. Vascular remodeling: implications for small artery function and target organ damage. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;1:129–137. doi: 10.1177/1753944707086358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stern N, Marcus Y. Perivascular fat: innocent bystander or active player in vascular disease? J Cardiometab Syndr. 2006;1:115–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-4564.2006.05510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Reactive oxygen species in vascular biology: implications in hypertension. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;122:339–352. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Rooijen N. Selective depletion of macrophages by liposome-encapsulated drugs. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Rooijen N, Sanders A. Elimination, blocking, and activation of macrophages: three of a kind? J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:702–709. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.6.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Rooijen N, Sanders A. Liposome mediated depletion of macrophages: mechanism of action, preparation of liposomes and applications. J Immunol Methods. 1994;174:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Rooijen N, Sanders A, van den Berg TK. Apoptosis of macrophages induced by liposome-mediated intracellular delivery of clodronate and propamidine. J Immunol Methods. 1996;193:93–99. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.You J, Johnson TD, Childres WF, Bryan RM., Jr Endothelial-mediated dilations of rat middle cerebral arteries by ATP and ADP. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H1472–H1477. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.3.H1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]