Abstract

Background

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are transmembrane proteins responsible for the efflux of a wide variety of substrates, including steroid metabolites, through the cellular membranes. For better characterization of the role of ABC transporters in prostate cancer (PCa) development, the profile of ABC transporter gene expression was analyzed in PCa and noncancerous prostate tissues (NPT).

Methods

TaqMan Low Density Array (TLDA) human ABC transporter plates were used for the gene expression profiling in 10 PCa and 6 NPT specimens. ABCB1 transcript level was evaluated in a larger set of PCa cases (N = 78) and NPT (N = 15) by real-time PCR, the same PCa cases were assessed for the gene promoter hypermethylation by methylation-specific PCR.

Results

Expression of eight ABC transporter genes (ABCA8, ABCB1, ABCC6, ABCC9, ABCC10, ABCD2, ABCG2, and ABCG4) was significantly down-regulated in PCa as compared to NPT, and only two genes (ABCC4 and ABCG1) were up-regulated. Down-regulation of ABC transporter genes was prevalent in the TMPRSS2-ERG-negative cases.

A detailed analysis of ABCB1 expression confirmed TLDA results: a reduced level of the transcript was identified in PCa in comparison to NPT (p = 0.048). Moreover, the TMPRSS2-ERG-negative PCa cases showed significantly lower expression of ABCB1 in comparison to NPT (p = 0.003) or the fusion-positive tumors (p = 0.002). Promoter methylation of ABCB1 predominantly occurred in PCa and was rarely detected in NPT (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

The study suggests frequent down-regulation of the ABC transporter genes in PCa, especially in the TMPRSS2-ERG-negative tumors.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12885-015-1689-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, ABC transporters, ABCB1

Background

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are transmembrane proteins responsible for the transfer of a wide variety of substrates through the extra- and intra-cellular membranes [1]. Cellular metabolites, lipids, sterols, drugs, and other xenobiotics are known as the substrates for ABC transporters. The human genome contains 51 ABC transporter genes (and pseudogenes) arranged in seven subfamilies and named from A to G [2]. In cancer cells, the over-expression of several ABC transporters is related to an increased efflux of chemotherapeutic drugs and the development of multidrug resistance [3]. The strongest connections with multidrug-resistant cancer have been identified for ABCB1 (also known as MDR1 or P-glycoprotein), ABCC1 (also known as MRP1), and ABCG2 (also known as BCRP or MXR) transporters. However, in prostate cancer (PCa), the highly prevalent male malignancy, the studies of ABC transporters are quite limited. Androgens and other steroid hormones are important for the normal development and maintenance of the prostate gland, but they also participate in prostate tumorigenesis. Androgen deprivation therapy through surgical or medical castration is an effective treatment strategy of PCa, but during the disease progression the sensitivity to residual androgens increases resulting in aggressive forms of castration-resistant PCa. Recent studies revealed strong connections between the steroid efflux capacities of ABC transporters and the progression of PCa [4].

ABCB1 is the most studied ABC transporter in PCa. Differently from other tumors, down-regulation rather than over-expression of the ABCB1 gene has been identified in PCa [5–7]. Aberrant DNA methylation and histone modifications are the main mechanisms responsible for the inactivation of this locus in PCa [7–9]. ABCB1 expression has been related to the efflux of androgens from PCa cell lines [10] suggesting that reduced levels of ABCB1 might be responsible for intratumoral androgen accumulation and sustained signaling from androgen receptors (ARs) [4]. ABCA1, another important transporter of the ABC family, was recently shown to be related to the development of aggressive PCa through the impaired efflux of cholesterol, an alternative source for androgen synthesis [11]. Several other ABC transporters were shown as the potent regulators of intracellular levels of steroid metabolites, including androgens and antiandrogens [12–14]. Additionally, expression of several ABC transporters was shown to be regulated by androgens or ARs [15, 16]. These data suggest significant involvement of ABC transporters in the pathogenesis of PCa and encourage more detailed analysis of gene expression of the ABC family in relation to clinical characteristics of PCa.

Gene expression profile of human ABC transporters was explored in cancerous and noncancerous prostate tissue by means of TaqMan Low Density Arrays (TLDA). Gene expression and DNA methylation of the ABCB1 gene were analyzed in a larger set of cases, and the data were correlated with clinical characteristics of PCa. Assessment of the TMPRSS2-ERG transcript status enabled identification of novel associations between this fusion transcript and the expression of ABC transporter genes.

Methods

Sample collection and clinical data

Prostate tissue samples were obtained from 104 PSA-screened and biopsy-proven PCa patients treated with a radical prostatectomy (RP) at the Vilnius University Urology Centre from 2008 to 2014. The research was a part of large-scale PCa biomarker study conducted according to standardised protocols of sample collection and processing reported previously [17]. Cancerous (≥70 % of tumor cells) and noncancerous (0 %) prostatectomy tissues were sampled by expert pathologist as previously reported [17] and prepared for molecular analysis. The results of clinical, postoperative pathological and molecular examinations are presented in Table 1. None of these patients had received preoperative radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or hormonal treatment. Approval from the Lithuanian Bioethics Committee was obtained before initiating the study and all patients gave informed consent for participation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study group. ABCB1 analysis group was involved in the ABCB1 gene expression and methylation analysis, while TLDA analysis group was profiled for the ABC transporter genes expression. NPT – noncancerous prostate tissue; PCa – prostate cancer; BCR – biochemical recurrence; PSA – prostate-specific antigen

| Variable | ABCB1 analysis group | TLDA analysis group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 93 | N = 16 | |||

| NPT | PCa | NPT | PCa | |

| N = 15 + 10a | N = 78 | N = 6 | N = 10 | |

| Mean age in years ± SEM | 62.13 ± 1.01 | 60.76 ± 0.85 | 61.33 ± 1.09 | 62.9 ± 2.04 |

| Pathological stage | ||||

| pT2 | 52 | 5 | ||

| pT3 | 25 | 5 | ||

| Gleason score | ||||

| 6 | 18 | 3 | ||

| ≥ 7 | 54 | 7 | ||

| Unknown | 1 | |||

| BCR | ||||

| Yes | 20 | 5 | ||

| No | 53 | 5 | ||

| Unknown | 5 | |||

| TMPRSS2-ERG status | ||||

| Positive | 51 | 6 | ||

| Negative | 27 | 4 | ||

| Mean PSA level at diagnosis, ng/ml ± SEM | 10.57 ± 1.25 | 11.07 ± 3.03 | ||

| Methylation status of ABCB1 promoter | ||||

| Methylated | 4 | 56 | 5 | |

| Unmethylated | 15 | 22 | 5 | |

| Unknown | 6 | 6 | ||

| Mean expression of ABCB1, ∆Cq ± SEM | 7.50 ± 0.24 | 8.14 ± 0.13 | 5.01 ± 0.18 | 5.61 ± 0.17 |

aTen additional samples were included in ABCB1 methylation analysis

Prostate tumors of a Gleason score 6–8 and of an intermediate stage (pT2-pT3) were included in our study (Table 1). Ten PCa and 6 noncancerous prostate tissues (NPT) were screened on human ABC transporter TLDA cards. The ABCB1 gene expression analysis was performed on 78 PCa tissues and 15 NPT specimens from PCa patients. The same (N = 78) PCa specimens and a set of NPT samples (N = 9) were analyzed for the ABCB1 gene promoter DNA methylation. Ten additional NPT samples were included in this analysis, resulting in a control group of 19 NPT specimens. Follow-up data were available for 93.59 % (73/78) of patients with a mean follow-up time of 3 years. Biochemical recurrence (BCR) was defined as a detection of serum PSA level of >0.20 ng/mL by two subsequent measurements after RP. The status of the fusion transcript TMPRSS2-ERG was identified as reported previously [17].

Gene expression analysis with TLDA

Total RNA from snap-frozen sections was isolated with mirVana Kit (Ambion, Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific Foster City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The quantity of the RNA samples was measured spectrophotometrically using the NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, NC, USA). Integrity (RIN) of the RNA samples was checked with the 2100 Bioanalyzer system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Reverse transcription (RT) was done using 500 ng of total RNA and High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit with RNase Inhibitor according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Foster city, CA, USA).

Gene expression of human ABC transporters was profiled using TLDA cards with the human ABC transporter panel (Applied Biosystems), containing 50 human ABC transporter genes and 14 proposed reference genes. Twenty μL of cDNA were used as a template for the measurement of mRNA in quantitative PCR (qPCR). RT-qPCR was performed using TaqMan Universal Master Mix II, no UNG from Applied Biosystems on the ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System as recommended by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems). Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 10 min, then 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min for 40 cycles.

Raw Cq-values with automatically selected thresholds were calculated using the ViiA 7 version 1.1 software (Applied Biosystems). Expression level of each gene for all samples was analyzed in triplicate and required at least two valid wells. Only genes having ≥70 % of valid data of all samples were involved in further analyses. According to the NormFinder and GeNorm algorithms the combination of POLR2A, PGK1, PPIA, ACTB, B2M, and HMBS was shown as the most suitable set of reference genes and was used for further TLDA data analysis.

Target gene RT-qPCR

Total RNA from snap-frozen sections was isolated using the phenol-chloroform method. Quantity of the RNA samples was measured spectrophotometrically using the NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For RT-qPCR, 1 μg of total RNA was converted to cDNA using Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit for RT-qPCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a final volume of 20 μL. RT products were amplified on Mastercycler-pro thermocycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) under the following conditions: 25 °C for 10 min, followed by 50 °C for 15 min, and the termination of reaction by heating at 85 °C for 5 min. A negative control without reverse transcriptase was included for each sample.

ABCB1 expression was analyzed by RT-qPCR with SYBR Green labeling using the following primers: F-5´-CCCATCATTGCAATAGCAGG-3´ and R-5´-GTTCAAACTTCTGCTCCTGA-3´. GAPDH was used as a reference gene and the product was amplified with the primers: F-5´-GAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTT-3´and R-5´-ATGGGTGGAATCATATTGGAAC-3´ (all from Metabion International AG, Martinsried, Germany).

RT-qPCR mix was prepared using Maxima SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (2X) (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.3 μM forward and reverse primers, and 2 μL cDNA in a total volume of 25 μL. Well-to-well variation was normalized by adding 10 nM ROX. QPCR was performed on the Viia7 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) under the following conditions: enzyme activation at 50 °C for 2 min followed by 95 °C for 10 min, then amplification at 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min for 40 cycles in total, and the melting step at default parameters. Cq values were calculated with Viia7 software version 1.1 (Applied Biosystems). All gene assays were measured in duplicate and required at least two valid wells. A negative control without cDNA was included for each primer pair in every RT-qPCR run.

DNA methylation analysis

Up to 20 mg of prostate tissue were digested with proteinase-K and DNA was extracted using standard phenol-chloroform protocol followed by ethanol precipitation. Modification with sodium bisulfite was performed using EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Bisulfite-modified DNA was used as a template for methylation-specific PCR (MSP) with ABCB1 primers [18] specific for either methylated or unmethylated DNA. The MSP reaction mix (25 μL) contained 1x AmpliTaq Gold Buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1.6 mM dNTP mix, 1.25 U AmpliTaq Gold 360 DNA Polymerase (Applied Biosystems), 0.5 μM of each primer, and 1 μL of bisulfite-modified DNA. Amplification conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 10 min, then 37 cycles at 95 °C for 45 s, 60 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 45 s, and final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The MSP products were run on 3 % agarose gel with ethidium bromide staining. Bisulfite-modified leukocyte DNA from healthy donors served as a negative control for methylated DNA and SssI methylase-treated (Thermo Fisher Scientific) bisulfite-modified leukocyte DNA served as a positive control. Non-template controls were included in each PCR run.

Statistical analysis

Computation of statistical tests was performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA) and GenEx version 6.0.1 software (MultiD Analyses AB, Göteborg, Sweden). Survival analysis of the TLDA cohort was carried out with MedCalc Statistical Software version 14.12.0 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). A t-test indicated relative gene expression differences between two groups. For methylation data, a Mann–Whitney U-test (for continuous variables) and a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test (for categorical variables) were applied to identify statistically significant differences between groups. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was calculated to identify significant associations. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Gene expression profile of ABC transporters in PCa

In order to explore the expression levels of the ABC genes, 10 PCa and 6 NPT samples were profiled on human ABC transporter TLDAs containing probes for 50 ABC genes in total. Expression of 45 genes was consistently identified in prostate tissue, with the highest levels (mean Cq < 24) characteristic to ABCA11, ABCC4, ABCD3, ABCE1, and ABCF3. In contrast, the ABCB5, ABCC12, ABCC13, ABCG5, and ABCG8 genes showed low or undetectable expression (mean Cq > 35) in prostate tissue and were eliminated from further analysis.

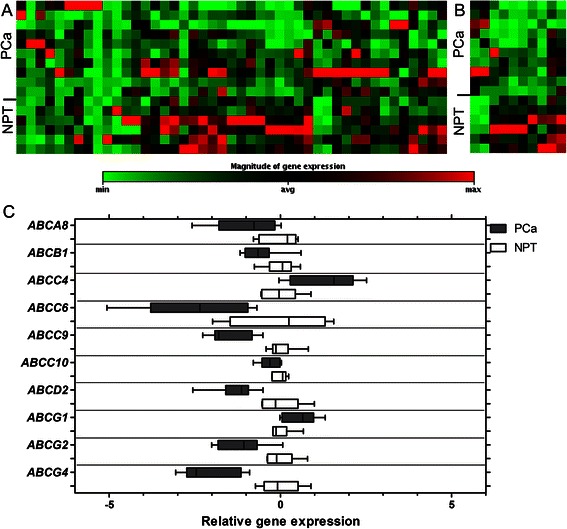

Comparison of PCa to NPT revealed a specific ABC gene expression signature of PCa characterized by marked down-regulation of several ABC transporter genes (Fig. 1a). Eight ABC transporter genes were significantly down-regulated in cancerous prostate tissues (Fig. 1b and c), including ABCA8 (FC 2.03; p = 0.029), ABCB1 (FC 1.52; p = 0.035), ABCC6 (FC 5.67; p = 0.005), ABCC9 (FC 2.77; p < 0.001), ABCC10 (FC 1.24; p = 0.030), ABCD2 (FC 2.44; p < 0.001), ABCG2 (FC 2.22; p = 0.003), and ABCG4 (FC 2.14; p < 0.001; Fig. 1c). Only two out of 45 analyzed ABC transporter genes, namely ABCC4 (FC 2.49; p = 0.007) and ABCG1 (FC 1.48; p = 0.029), were up-regulated in PCa in comparison to NPT (Fig. 1b and c, Additional file 1).

Fig. 1.

Profile of ABC transporter gene expression in prostate cancer (PCa) and noncancerous prostate tissue (NPT). Heat maps represent expression profile of all analyzed (a) and significantly (p < 0.05) deregulated (b) ABC genes. Box plots (c) show expression levels of significantly deregulated ABC genes. The box extends from the 25th to 75th percentiles. The line in the middle of the box is plotted at the median. The whiskers indicate the smallest and largest values

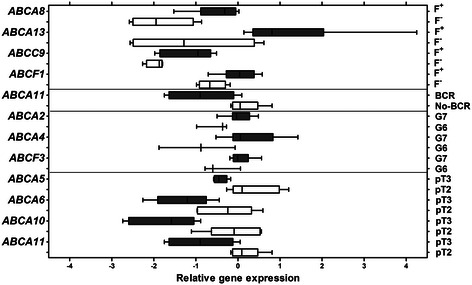

Remarkably, a quite different profile of ABC gene expression was observed in PCa stratified according to the TMPRSS2-ERG transcript status. ABCA8 and ABCC9, the genes that were significantly down-regulated in PCa in comparison to NPT, showed high expression in the TMPRSS2-ERG-positive cases, but were suppressed in the fusion-negative cases. The total list of ABC transporters that were down-regulated in the TMPRSS2-ERG-negative cases included ABCA8 (FC 2.56; p = 0.012), ABCA13 (FC 5.35; p = 0.039), ABCC9 (FC 1.74; p = 0.037), and ABCF1 (FC 1.57; p = 0.038; Fig. 2, Additional file 1).

Fig. 2.

Significant changes (p < 0.05) of ABC transporter gene expression in PCa according to selected variables. F+/− − TMPRRS2-ERG fusion status; BCR – biochemical recurrence; G7/6 – Gleason score 7/6; pT3/2 – pathological tumor stage 3/2. The box extends from the 25th to the 75th percentiles. The line in the middle of the box is plotted at the median. The whiskers indicate the smallest and largest values

PCa cases that experienced BCR (N = 5) showed significant reduction of the ABCA11 gene expression (FC 2.03; p = 0.031; Additional file 1). The expression level of ABCA11 was negatively correlated with tumor size (R −0.83; p = 0.003) and extra-prostatic tumor stage (FC 2.05; p = 0.028). Univariate survival analysis revealed borderline significance of ABCA11 expression (p = 0.072) in predicting BCR.

In addition to ABCA11, the extra-prostatic tumor stage (pT3 vs pT2) was associated with the down-regulation of other ABC transporter genes from subfamily A (Fig. 2, Additional file 1): ABCA5 (FC 1.73; p = 0.022), ABCA6 (FC 2.00; p = 0.046), and ABCA10 (FC 3.29; p = 0.006). In contrast, the higher Gleason score (Gleason 7 vs 6) was related to over-expression of several genes: ABCA2 (FC 1.47; p = 0.041), ABCA4 (FC 2.41; p = 0.038), and ABCF3 (FC 1.44; p = 0.041). This might be explained by the predominance of the TMPRSS2-ERG-positive cases among tumors with Gleason score 7.

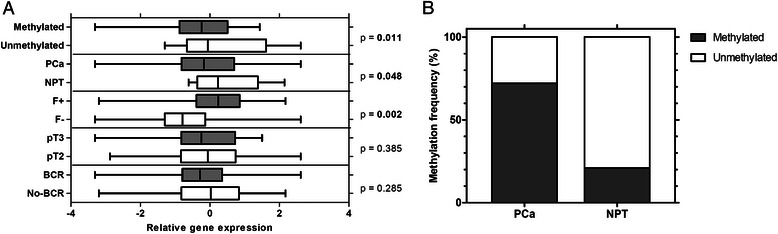

ABCB1 expression and DNA methylation in PCa

For the verification of TLDA results, expression of the ABCB1 gene was evaluated in a larger group of PCa cases (N = 78) and NPT (N = 15) specimens. As in the TLDA analysis, the ABCB1 expression was significantly lower in PCa than in NPT tissues (FC 1.56; p = 0.048; Fig. 3a). Moreover, the TMPRSS2-ERG-negative PCa cases showed significantly lower ABCB1 expression in comparison to the fusion-positive tumors (FC 1.77; p = 0.002) or NPT (FC 2.90; p = 0.003). A negative association (R −0.29; p = 0.012) was detected between ABCB1 expression and the preoperative PSA level. No other significant correlations with clinical variables (pT or Gleason score) were identified, and similar levels of ABCB1 were observed in BCR and no-BCR cases (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Expression levels (a) and methylation frequency (b) of ABCB1 in prostate tissues. PCa – prostate cancer; NPT – noncancerous prostate tissue; BCR – biochemical recurrence; F+/− – TMPRRS2-ERG fusion status. The box of figure A extends from the 25th to the 75th percentiles. The line in the middle of the box is plotted at the median. The whiskers indicate the smallest and largest values

The MSP analysis (Fig. 3b) was applied for the detection of aberrant DNA methylation in the promoter region of the ABCB1 gene in the same set of PCa cases. More than 70 % of PCa tissues (56/78; 71.79 %) showed aberrant ABCB1 promoter methylation, while this change rarely occurred in NPT specimens (4/19; p < 0.001). Comparison to gene expression data revealed statistically significantly lower levels the ABCB1 transcript in the PCa tissues with the promoter hypermethylation as compared to the cases without hypermethylation (FC 1.66; p = 0.011; Fig. 3a). Similarly to the gene expression, no statistically significant correlations between the ABCB1 methylation status and clinical variables were identified.

CpG islands of the ABC transporter genes

To test the possible involvement of DNA methylation in transcriptional regulation of other ABC genes, CpG islands (CGI) of the significantly deregulated ABC promoters were characterized based on data provided by the NCBI Epigenomics browser. For genes with no CGIs present, the DBCAT online tool [19] was used to predict potential CGIs, applying the following parameters: observed/expected CpG ratio 0.6, minimal CGI length 300 bp, and GC content ≥50 %. Promoter regions were obtained from the Swiss Regulon Portal [20] or from the Eukaryotic Promoter Database [21]. Typical CGIs were identified in 5’ regions in 12 out of 19 (74 %) significantly deregulated ABC genes, and 2 additional CGIs were predicted using CGI detection tool (Table 2). Mean length of the identified CGIs was more than 1 kb, the GC content exceeded 70 %, and most of the CGIs were located in the promoter regions of the ABC genes. Only two out of these 14 CGIs of the ABC genes (ABCB1 and ABCG2) have been studied for DNA methylation changes in PCa [7–9, 22–24], while others deserve further investigations.

Table 2.

Characterization of CpG islands (CGIs) of significantly deregulated ABC transporter genes. CGI locations are provided relative to transcription start site (TSS). Gene expression changes were identified in comparisons: Gleason score 7 versus 6 (G7/6); tumor stage 3 versus 2 (pT3/2); prostate cancer versus noncancerous prostate tissue (PCa/NPT); TMPRSS2-ERG fusion transcript negative versus positive cases (F−/+)

| Gene name | Gene expression | Group comparison | Gene location | CGI presence | GC content, % | CGI length, bp | CGI location according to TSS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCA2 | Up | G7/6 | 9q34 | Yes | 78 | 1196 | +134/+1329 |

| ABCA4 | Up | G7/6 | 1p22 | No | – | – | – |

| ABCA5 | Down | pT3/2 | 17q24.3 | Yes | 67 | 1319 | −669/+650 |

| ABCA6 | Down | pT3/2 | 17q24.3 | No | − | − | − |

| ABCA8 | Down | PCa/NPT; F−/+ | 17q24 | No | − | − | − |

| ABCA10 | Down | pT3/2 | 17q24 | No | − | − | − |

| ABCA11 | Down | BCR+/−; pT3/2 | 4p16.3 | Yes | 63 | 724 | −10/+714 |

| ABCA13 | Down | pT3/2; F−/+ | 7p12.3 | Yesa | 62 | 618 | +283291/+283908 |

| ABCB1 | Down | PCa/NPT; F−/+; pT3/2 | 7q21.12 | Yes | 57 | 1048 | +112174/+113221 |

| ABCC4 | Up | PCa/NPT | 13q32 | Yes | 68 | 1355 | −849/+506 |

| ABCC6 | Down | PCa/NPT | 16p13.1 | Yesa | 58 | 1397 | −1022/+375 |

| ABCC9 | Down | PCa/NPT; F−/+ | 12p12.1 | Yes | 56 | 1019 | −733/+286 |

| ABCC10 | Down | PCa/NPT | 6p21.1 | Yes | 59 | 964 | −454/+510 |

| ABCD2 | Down | PCa/NPT | 12q12 | No | − | − | − |

| ABCF1 | Down | F−/+ | 6p21.33 | Yes | 58 | 1222 | −655/+567 |

| ABCF3 | Up | G7/6 | 3q27.1 | Yes | 62 | 737 | −269/+468 |

| ABCG1 | Up | PCa/NPT | 21q22.3 | Yes | 67 | 1709 | −437/+1272 |

| ABCG2 | Down | PCa/NPT | 4q22 | Yes | 65 | 1053 | −589/+464 |

| ABCG4 | Down | PCa/NPT | 11q23.3 | Yes | 73 | 888 | −262/+626 |

aPredicted CGI

Discussion

Current evidence suggests a role for membrane transporters in control of intratumoral androgen level important for PCa development and progression [10–14]. In the present study, for the better characterization of the role of ABC transporters in prostate tumorigenesis, expression levels of all human ABC transporter genes were evaluated for the first time in cancerous and noncancerous prostate tissue. This study identified a specific profile of ABC gene expression in PCa characterized by the down-regulation of several ABC genes. Deregulated expression of a set of ABC genes was particularly evident in the TMPRSS2-ERG-negative prostate tumors.

Expression of 45 out of 50 ABC transporter genes loaded on the array was identified in prostate tissue, while five genes showed low or undetectable levels of expression. Transcription levels of eight ABC transporter genes, including ABCA8, ABCB1, ABCC6, ABCC9, ABCC10, ABCD2, ABCG2, and ABCG4, were significantly down-regulated in PCa, and only two genes, ABCC4 and ABCG1, were up-regulated. In a larger set of PCa cases, the expression of ABCB1 was also significantly reduced in PCa relative to NPT, and this suppression was associated with increased preoperative PSA level. Our data are in agreement with other studies of ABC transporters in PCa. Several studies reported the down-regulation of the ABCB1 gene [5–7] and reduced levels of protein expression [9] in PCa in comparison to NPT. Similarly, loss of the ABCA1 protein expression was detected in PCa, especially in the higher grade tumors [11]. The ABCA5 protein was detectable in basal cells of normal prostate glands and premalignant lesions, but was faintly expressed in prostate cancer glands [25]. Down-regulation of the ABCC4 or ABCG2 transporters was recently reported in PCa [16, 23]. Expression of ABCC4 was shown to be reduced after androgen ablation, and castration-resistant PCa cases had lower levels of this transporter [15, 16]. Expression or functional activities of the remaining members of this large gene family are mainly unexplored in PCa.

DNA hypermethylation is a powerful mechanism of gene inactivation. In PCa, aberrant DNA methylation of the ABCB1 promoter was reported in several studies, and correlations with reduced gene or protein expression were identified [7–9, 26, 27]. In agreement with these previous studies, our data showed frequent (72 %) hypermethylation of the ABCB1 promoter in PCa, and significant association between the aberrant methylation and reduced expression of the transcript. Similarly, the loss of expression of ABCA1, another transporter of the ABC family, was recently [11] related to the aberrant methylation of the promoter region in PCa. Besides, comparison of the global methylation pattern of genes in PCa cell lines and normal prostate cell lines [7] revealed predominant hypermethylation of different membrane transporter genes in PCa cell lines. Among them, two genes of the ABC family, ABCB1 and ABCC7, showed increased methylation in PCa cell lines. Similarly, hypermethylation of the ABCC6 gene was identified in urine of bladder cancer patients [28]. This suggests that frequent down-regulation of ABC transporter genes in PCa, observed in our study and in other publications [5–7, 11, 16, 23] might be caused by the gain of DNA methylation in ABC gene loci. In support of this concept, strong CpG islands were identified in loci encoding 14 out of 19 ABC genes that were deregulated in PCa tissues in our study. This observation encourages further investigation of epigenetic aberrations of ABC transporter genes in PCa as a possible mechanism of prostate tumorigenesis and PCa progression.

Although the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion is the most prevalent genetic rearrangement found in approximately 50 % of PCa [29], the clinical implications of this gene fusion are still unclear. The fusion transcript is usually composed of the androgen-sensitive TMPRSS2 promoter and the ERG sequence. This genetic rearrangement results in the androgen-regulated oncogenic transcription factor. In our study, despite the predominant down-regulation of ABC transporters in PCa specimens, the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion-positive tumors showed quite high levels of ABCB1 and several other ABC genes in comparison to the fusion-negative cases. cMYC, which is a direct transcriptional regulator of a large set of ABC transporters, is usually over-expressed in the fusion-positive PCa [30] and might be responsible for this TMPRSS2-ERG fusion-related ABC gene expression profile. More importantly, our study revealed marked down-regulation of four ABC transporter genes (ABCA8, ABCA13, ABCC9, and ABCF1) in the subgroup of PCa cases that were negative for the TMPRSS2-ERG transcript. In addition, the expression of ABCB1 was also significantly reduced in the TMPRSS2-ERG-negative cases in our validation study. The altered expression of ABC transporters has been shown to reduce the efflux of androgens and their precursors [4], while intracellular accumulation of androgens is responsible for sustained AR signaling. This ABC transporters deficiency-related AR activation might serve as an important pathway of tumorigenesis in TMPRSS2-ERG-negative cases. Moreover, these changes in ABC gene expression might favor development of a progressive, anti-androgen therapy-resistant phenotype of PCa. However, the exact mechanism and consequences of the down-regulation of ABC transporter genes in PCa need to be clarified in functional studies.

PCa is a highly variable disease with multiple genetic and epigenetic alterations affecting a wide range of biological pathways. During recent years multiple molecular markers of PCa have been explored, however, the implication of ABC transporters in prostate cancerogenesis is still poorly understood. Besides extensively documented hypermethylation of the ABCB1 promoter, our study demonstrates that down-regulation of other ABC transporter genes occurs in PCa. Deregulated expression of several ABC genes shows significant associations with advanced tumor stage, grade, other clinical variables, and TMPRSS2-ERG status. Moreover, our data indicate that a set of these significantly deregulated ABC genes possess strong CGIs in their promoters and might be controlled by DNA methylation and other epigenetic phenomena. Significantly deregulated ABC genes identified by our TLDA-based screening warrant further investigation for their diagnostic and prognostic potential in PCa, whereas epigenetic therapy might be considered for treatment of androgen deprivation therapy-resistant tumors.

Conclusions

In prostate tumors, expression of several ABC transporter genes is down-regulated and shows significant associations with clinical variables and the absence of the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion transcript. ABCB1 analysis and characterization of CpG islands of the ABC loci suggest aberrant DNA methylation as a plausible mechanism inactivating expression of the ABC transporter genes in PCa.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by grant No. LIG-14/2012 from the Research Council of Lithuania. Dr. Elizabeth Georgian is kindly acknowledged for the language editing. We thank Lina Gasiunaite and Mantas Lukosius for participation in ABCB1 analyses.

Additional file

Significant changes (p < 0.05) of ABC transporter gene expression in different comparisons of subgroups. PCa – prostate cancer; NPT – noncancerous prostate tissue; BCR – biochemical recurrence; TMPRSS2-ERG+/- – fusion transcript positive/negative cases; pT – tumour stage; FC – fold change. (XLSX 10 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RD performed the TLDA experiments, analyzed ABCB1 expression, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. DR performed the characterization of CGIs and analyzed TMPRSS2-ERG status. KD performed the gene methylation analyses. FJ supplied the samples and clinical data and helped to draft the manuscript. JRL coordinated the sample and data collection, was responsible for the granting. SJ conceived and designed the study and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Rita Demidenko, Email: rita.demidenko@gmail.com.

Deividas Razanauskas, Email: dei.razanauskas@gmail.com.

Kristina Daniunaite, Email: kristina.daniunaite@gf.vu.lt.

Juozas Rimantas Lazutka, Email: juozas.lazutka@gf.vu.lt.

Feliksas Jankevicius, Email: feliksas.jankevicius@santa.lt.

Sonata Jarmalaite, Email: sonata.jarmalaite@gf.vu.lt.

References

- 1.Vasiliou V, Vasiliou K, Nebert DW. Human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family. Hum Genomics. 2009;3:281–290. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-3-3-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allikmets R, Gerrard B, Hutchinson A, Dean M. HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee database HGNC. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1649–1655. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.10.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fletcher JI, Haber M, Henderson MJ, Norris MD. ABC transporters in cancer: more than just drug efflux pumps. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:147–156. doi: 10.1038/nrc2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho E, Montgomery RB, Mostaghel EA. Minireview: SLCO and ABC Transporters: A Role for Steroid Transport in Prostate Cancer Progression. Endocrinology. 2014;155:4124–4132. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhangal G, Halford S, Wang J, Roylance R, Shah R, Waxman J. Expression of the multidrug resistance gene in human prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2000;5:118–121. doi: 10.1016/S1078-1439(99)00055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawai K, Sakurai M, Sakai T, Misaki M, Kusano I, Shiraishi T, et al. Demonstration of MDR1 P-glycoprotein isoform expression in benign and malignant human prostate cells by isoform-specific monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Lett. 2000;150:147–153. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(99)00384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishra DK, Chen Z, Wu Y, Sarkissyan M, Koeffler HP, Vadgama JV. Global methylation pattern of genes in androgen-sensitive and androgen-independent prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:33–45. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enokida H, Shiina H, Igawa M, Ogishima T, Kawakami T, Bassett WW, et al. CpG hypermethylation of MDR1 gene contributes to the pathogenesis and progression of human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5956–5962. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henrique R, Oliveira AI, Costa VL, Baptista T, Martins AT, Morais A, et al. Epigenetic regulation of MDR1 gene through post-translational histone modifications in prostate cancer. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:898. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fedoruk MN, Giménez-Bonafé P, Guns ES, Mayer LD, Nelson CC. P-glycoprotein increases the efflux of the androgen dihydrotestosterone and reduces androgen responsive gene activity in prostate tumor cells. Prostate. 2004;59:77–90. doi: 10.1002/pros.10354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee BH, Taylor MG, Robinet P, Smith JD, Schweitzer J, Sehayek E, et al. Dysregulation of cholesterol homeostasis in human prostate cancer through loss of ABCA1. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1211–1218. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imai Y, Asada S, Tsukahara S, Ishikawa E, Tsuruo T, Sugimoto Y. Breast cancer resistance protein exports sulfated estrogens but not free estrogens. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:610–618. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.3.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zelcer N, Reid G, Wielinga P, Kuil A, van der Heijden I, Schuetz JD, et al. Steroid and bile acid conjugates are substrates of human multidrug-resistance protein (MRP) 4 (ATP-binding cassette C4) Biochem J. 2003;371:361–367. doi: 10.1042/bj20021886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huss WJ, Gray DR, Greenberg NM, Mohler JL, Smith GJ. Breast cancer resistance protein-mediated efflux of androgen in putative benign and malignant prostate stem cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6640–6650. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho LL, Kench JG, Handelsman DJ, Scheffer GL, Stricker PD, Grygiel JG, et al. Androgen regulation of multidrug resistance-associated protein 4 (MRP4/ABCC4) in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2008;68:1421–1429. doi: 10.1002/pros.20809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montani M, Hermanns T, Müntener M, Wild P, Sulser T, Kristiansen G. Multidrug resistance protein 4 (MRP4) expression in prostate cancer is associated with androgen signaling and decreases with tumor progression. Virchows Arch. 2013;462:437–443. doi: 10.1007/s00428-013-1390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabaliauskaite R, Jarmalaite S, Petroska D, Dasevicius D, Laurinavicius A, Jankevicius F, Lazutka JR. Combined analysis of TMPRSS2-ERG and TERT for improved prognosis of biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:781–791. doi: 10.1002/gcc.21963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao P, Yang X, Xue YW, Zhang XF, Wang Y, Liu WJ, et al. Promoter methylation of glutathione S-transferase pi1 and multidrug resistance gene 1 in bronchiole alveolar carcinoma and its correlation with DNA methyltransferase 1 expression. Cancer. 2009;115:3222–3232. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuo HC, Lin PY, Chung TC, Chao CM, Lai LC, Tsai MH, et al. DBCAT: database of CpG islands and analytical tools for identifying comprehensive methylation profiles in cancer cells. J Comput Biol. 2011;18:1013–1017. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2010.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pachkov M, Erb I, Molina N, van Nimwegen E. Swiss Regulon: a database of genome-wide annotations of regulatory sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D127–D131. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cavin Périer R, Junier T, Bucher P. The Eukaryotic Promoter Database EPD. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:353–357. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellinger J, Bastian PJ, Jurgan T, Biermann K, Kahl P, Heukamp LC, et al. CpG island hypermethylation at multiple gene sites in diagnosis and prognosis of prostate cancer. Urology. 2008;71:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guzel E, Karatas OF, Duz MB, Solak M, Ittmann M, Ozen M. Differential expression of stem cell markers and ABCG2 in recurrent prostate cancer. Prostate. 2014;74:1498–1505. doi: 10.1002/pros.22867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu T, Xu F, Du X, Lai D, Liu T, Zhao Y, et al. Establishment and characterization of multi-drug resistant, prostate carcinoma-initiating stem-like cells from human prostate cancer cell lines 22RV1. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;340:265–273. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0426-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu Y, Wang M, Veverka K, Garcia FU, Stearns ME. The ABCA5 protein: a urine diagnostic marker for prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:929–938. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yegnasubramanian S, Kowalski J, Gonzalgo ML, Zahurak M, Piantadosi S, Walsh PC, et al. Hypermethylation of CpG islands in primary and metastatic human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1975–1986. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enokida H, Shiina H, Urakami S, Igawa M, Ogishima T, Li LC, et al. Multigene methylation analysis for detection and staging of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6582–6588. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu J, Zhu T, Wang Z, Zhang H, Qian Z, Xu H, et al. A novel set of DNA methylation markers in urine sediments for sensitive/specific detection of bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:7296–7304. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, Dhanasekaran SM, Mehra R, Sun XW, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun C, Dobi A, Mohamed A, Li H, Thangapazham RL, Furusato B, et al. TMPRSS2-ERG fusion, a common genomic alteration in prostate cancer activates C-MYC and abrogates prostate epithelial differentiation. Oncogene. 2008;27:5348–5353. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]