Abstract

Objective Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a rare liver disorder, usually manifesting in the third trimester and associated with increased perinatal morbidity and mortality. The hallmark laboratory abnormality in ICP is elevated fasting serum bile acids; however, there are limited data on whether a nonfasting state affects a pregnant woman's total bile acids. This study assesses fasting and nonfasting bile acid levels in 10 healthy pregnant women after a standardized glucose load to provide insight into the effects of a glucose load on bile acid profiles.

Study Design Pilot prospective cohort analysis of serum bile acids in pregnant women. A total of 10 healthy pregnant women from 28 to 32 weeks' gestation were recruited for the study before undergoing a glucose tolerance test. Total serum bile acids were collected for each subject in the overnight fasting state, and 1 and 3 hours after the 100-g glucose load.

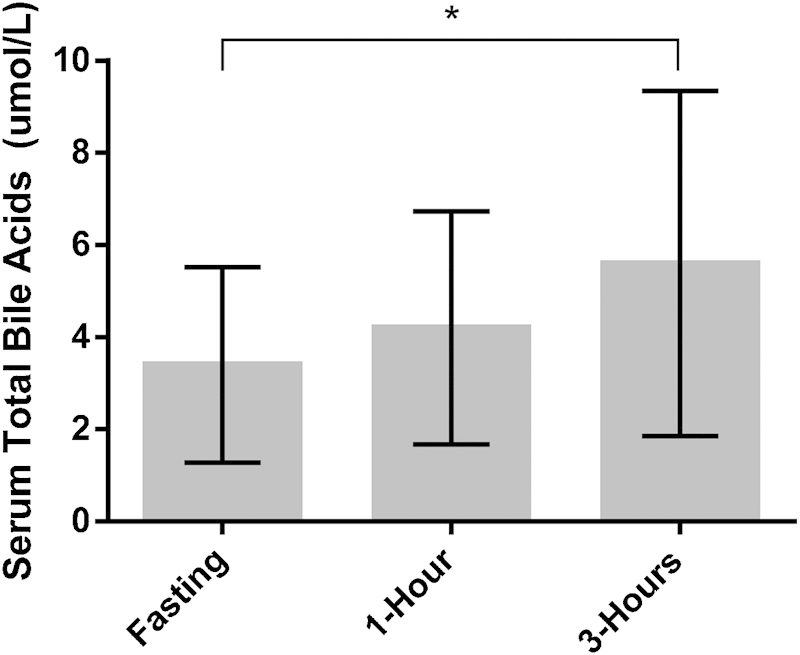

Results There was a statistically significant difference between fasting versus 3-hour values. There was no statistically significant difference between fasting versus 1-hour and 1-hour versus 3-hour values.

Conclusion There is a difference between fasting and nonfasting total serum bile acids after a 100-g glucose load in healthy pregnant women.

Keywords: bile acids, cholestasis, pregnancy, liver disease

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a rare liver disorder which usually manifests in the third trimester.1 2 3 4 5 ICP commonly presents with severe pruritus and elevated liver function tests. The pruritus may precede physical or laboratory abnormalities and is characterized by total body itching with predominance for the palms and soles of the feet. Skin lesions are generally absent, aside from excoriations from scratching and symptoms are frequently worse at night. Most patients are otherwise healthy and the disorder resolves days to weeks after delivery.1 2 3 6 7 For the pregnant woman, ICP is typically a transient and benign process, however, fetal complications include an increased risk of fetal distress, spontaneous preterm labor, and unexplained stillbirth.1 5 8 9 10 11 12 13

The incidence of ICP ranges from 0.5 to 1.8% in Europe, but it is significantly higher in South America where Chile has a reported incidence of up to 28%.2 3 14 15 In the United States, the estimated prevalence of ICP is from 0.001 to 0.32%, however, there is clear ethnic variation as the prevalence may be as high as 5.6% in Hispanic populations.1 14 15 16 The pathogenesis of ICP is multifactorial, involving genetic susceptibility, abnormalities in hormone metabolism, and possible environmental factors.3 Although the exact etiology of ICP is unclear, the increased hormone levels in pregnancy may have a strong influence on the disease process.1 2 16 17 There may also be subclinical physiologic cholestasis during pregnancy, which is exacerbated in individuals with some genetic or environmental predisposition.18

Elevation of total bile acids (TBA) is the most frequent laboratory abnormality associated with ICP and is the most sensitive marker for ICP.1 14 15 18 19 Bile acids are the end products of cholesterol catabolism with their most recognized functions being to aid in the digestion and absorption of fatty acids in the intestine. Bile acids are actively secreted by the liver into bile and stored in the gall bladder, which secretes them into the lumen of the intestine after ingestion of the meal. The efficiency of the hepatic clearance of bile acids from portal blood maintains serum concentrations at low levels in normal persons. Therefore, an elevated fasting level, because of the impaired hepatic clearance, is a sensitive indicator of liver disease.7 17 20 21 Following meals, serum bile acid levels have been shown to increase only slightly in normal persons, but markedly in patients with various liver diseases, including cirrhosis, hepatitis, cholestasis, portal-vein thrombosis, Budd-Chiari syndrome, cholangitis, Wilson disease, and hemochromatosis.17 20 22

Despite the potential impact of bile acids on fetal morbidity and mortality, there is a paucity of information regarding the temporal changes of serum bile acids during pregnancy. This is confounded by not only the wide range of values for the diagnosis of ICP in the current literature, but also the fact that the current reference ranges are generally for fasting values of TBA and generally exclude values from pregnant subjects.5 11 16 23 24 25 26 27 28 Confusing the situation further, while elevated fasting serum bile acids is the most sensitive marker for the diagnosis of ICP, many obstetricians order serum bile acids when the clinical suspicion for ICP arises and the patient is very unlikely to be fasting.12 13 To understand ICP, it is important to understand the relationship between fasting TBA and nonfasting TBA in pregnant women. We sought to determine the impact of a glucose load on the TBA levels in healthy pregnant women and hypothesized that the nonfasting state would transiently elevate TBA, which may complicate the diagnosis of ICP.

Methods

This prospective pilot study evaluated the fasting and nonfasting TBA levels of healthy pregnant women at Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN from September 2012 to January 2013. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (HSR number 12–3436). Women were recruited for the study if they were undergoing a 3-hour glucose tolerance test.

Overall, 10 healthy pregnant women older than 18 years with a singleton pregnancy who were undergoing a 3-hour glucose tolerance test and confirmed to be fasting were recruited and enrolled in the study. Pregnant women with a history of liver disease or gall bladder disease, including hepatitis, alcohol abuse, and history of gastric bypass surgery or current unexplained pruritus were excluded. All women were given a copy of the study consent form and written informed consent was obtained. Those who met study inclusion criteria also completed a short survey which collected information on demographics and medical, surgical, and family history.

Serum TBA levels were collected in the overnight fasting state and then 1 and 3 hours after a 100 g glucose load. The samples were then processed and stored at −20°C until all 10 recruited patients had delivered. The frozen serum samples were analyzed via enzymatic colorimetric assay (ARUP laboratories in Salt Lake City, UT) for the determination of TBA. The TBA reference interval of 0 to 10 µmol/L was based on fasting specimens.

Demographic and medical history data were summarized and reported as frequencies and percentages or mean ± standard deviation (SD) as appropriate unless otherwise indicated. Serum TBA levels were compared over time using a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) model assuming a compound symmetry covariance structure and pairwise comparisons were conducted. As this was a pilot study, p values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed using SAS (Version 9.3, Cary, NC) and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the 10 study participants are described in Table 1. Of the participants, five (50%) were multiparous and five (50%) were primaparous. The study population was predominately Caucasian (40%) and the mean gestational age at enrollment was 29 weeks + 6 days (range, 28 weeks + 1 day to 31 weeks + 1 day). The mean gestational age at delivery of the cohort was 39 weeks + 4 days (range, 37 weeks + 0 days to 41 weeks + 3 days).

Table 1. Demographic and medical history of pilot study participants.

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Parity | |

| Primparous | 5 (50) |

| Multiparous | 5 (50) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Caucasian, nonHispanic | 4 (40) |

| African, nonHispanic | 3 (30) |

| Other, Hispanic/Latina | 3 (30) |

| Country of origin | |

| Mexico | 3 (30) |

| Somalia | 3 (30) |

| United States | 4 (40) |

| Smoking status | |

| No | 9 (90) |

| Yes | 1 (10) |

| Other medical conditions | |

| None | 9 (90) |

| Hypertension | 1 (10) |

| History of abdominal surgery | |

| No | 9 (90) |

| Yes | 1 (10) |

| Mean ± SD | |

| Mother age at study (y) | 30.1 ± 4.6 |

| Gestational age at study (wk) | 29 wk 6 d ± 1 wk |

| Fasting total serum bile acids (µmol/L) | 3.4 ± 2.1 |

Mean serum TBA levels increased over time from 3.4 ± 2.1 µmol/L at fasting, 4.2 ± 2.5 µmol/L at 1 hour post glucose load, and 5.6 ± 3.7 µmol/L at 3 hours post glucose load (Fig. 1). There was a statistically significant change in serum TBA levels over time (F2,18 = 3.42, p = 0.05). Specifically, while the differences in serum TBA levels between the fasting and 1 hour (p = 0.36) and 1 and 3 hours (p = 0.12) were not statistically significant, the mean serum TBA levels at 3 hours were statistically significantly higher than the fasting serum TBA levels (p = 0.02).

Fig. 1.

Mean serum total bile acid levels (µmol/L) at each time point. Error bars represent standard deviation.* indicates comparison between time points has p value less than 0.05.

Discussion

Our pilot study investigated the effects of a glucose load on serum TBA levels in healthy pregnant women. There is currently a lack of information regarding the effects of the nonfasting state on serum TBA in pregnant subjects. Our study is one of the first to compare fasting and nonfasting levels of TBA in a healthy pregnant population in the United States. Our results highlight the small, but statistically and likely clinically significant difference in serum TBA between fasting and 3-hour post glucose load samples in a small population of healthy pregnant women. Barnes et al reported that in the healthy nonpregnant population, TBA levels return to fasting levels shortly after a meal,20 however, in our study, the mean TBA levels remained significantly higher than fasting values at 3 hours. This result is consistent with observations that normal pregnancy is a cholestatic state, as it has been reported that up to 40% of asymptomatic women may have a postprandial TBA value > 10 µmol/L.16 29 30 Should postprandial serum TBA levels be used to diagnose ICP? Our results indicate that even in the healthy pregnant population, the postprandial state affects serum TBA levels for hours. Fasting TBA levels may be the most sensitive indicator of severe liver disease for pregnant patients as postprandial levels may be elevated at baseline.20 26 However, there may be a role for the interpretation of nonfasting TBA, as elevated TBA in the nonfasting state from delayed clearance may be an early indicator of mild disease.20 31

Overall, this pilot study, while small, suggests that in our population the standard fasting reference ranges for serum TBAs are appropriate. This is consistent with previous studies to determine the reference range for total serum bile acids in the pregnant population.16 26 This study also provides important initial data on how a glucose load affects the range of bile acids in the healthy pregnant population and it appears that fasting serum TBA levels remain the most appropriate form of evaluation. These data will assist in resolving the current diagnostic dilemma with ICP, in particular, when should the obstetrician obtain the specimen for serum TBAs as well as how to determine the appropriate normal range in the pregnant population. Further studies using a lipid containing test meal would provide more physiologic data and a larger study is needed to further support these findings.

Acknowledgment

Funding was provided by Minnesota Medical Research Foundation. There are no financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Note

This article was presented as a poster at the 80th Annual Meeting for the Central Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, October 16 to 18, 2013.

References

- 1.Pathak B, Sheibani L, Lee R H. Cholestasis of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2010;37(2):269–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bull L N, Vargas J. Serum bile acids in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: not just a diagnostic test. Hepatology. 2014;59(4):1220–1222. doi: 10.1002/hep.26888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Floreani A, Caroli D, Lazzari R. et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: new insights into its pathogenesis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26(14):1410–1415. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.783810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoong W, Memtsa M, Pun S, West P, Loo C, Okolo S. Pregnancy outcomes of women with pruritus, normal bile salts and liver enzymes: a case control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87(4):419–422. doi: 10.1080/00016340801976079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webb G J, Elsharkawy A M, Hirschfield G M. The etiology of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: towards solving a monkey puzzle. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(1):85–88. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Deng W, Wang J, Shao Y, Ou M, Ding M. Primary bile acids as potential biomarkers for the clinical grading of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;122(1):5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullally B A, Hansen W F. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002;57(1):47–52. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200201000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tribe R M, Dann A T, Kenyon A P, Seed P, Shennan A H, Mallet A. Longitudinal profiles of 15 serum bile acids in patients with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(3):585–595. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kondrackiene J, Beuers U, Zalinkevicius R, Tauschel H D, Gintautas V, Kupcinskas L. Predictors of premature delivery in patients with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(46):6226–6230. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i46.6226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geenes V, Chappell L C, Seed P T, Steer P J, Knight M, Williamson C. Association of severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with adverse pregnancy outcomes: a prospective population-based case-control study. Hepatology. 2014;59(4):1482–1491. doi: 10.1002/hep.26617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arthur C, Mahomed K. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: diagnosis and management; a survey of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology fellows. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;54(3):263–267. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker I A, Nelson-Piercy C, Williamson C. Role of bile acid measurement in pregnancy. Ann Clin Biochem. 2002;39(Pt 2):105–113. doi: 10.1258/0004563021901856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker I, Chappell L C, Williamson C. Abnormal liver function tests in pregnancy. BMJ. 2013;347:f6055. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egan N, Bartels A, Khashan A S. et al. Reference standard for serum bile acids in pregnancy. BJOG. 2012;119(4):493–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee R H, Ouzounian J G, Goodwin T M. et al. Bile acid concentration reference ranges in a pregnant Latina population. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30(5):389–393. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee R H, Goodwin T M, Greenspoon J, Incerpi M. The prevalence of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy in a primarily Latina Los Angeles population. J Perinatol. 2006;26(9):527–532. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frise C J, Williamson C. Gastrointestinal and liver disease in pregnancy. Clin Med. 2013;13(3):269–274. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.13-3-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bacq Y, Zarka O, Bréchot J F. et al. Liver function tests in normal pregnancy: a prospective study of 103 pregnant women and 103 matched controls. Hepatology. 1996;23(5):1030–1034. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lunzer M, Barnes P, Byth K, O'Halloran M. Serum bile acid concentrations during pregnancy and their relationship to obstetric cholestasis. Gastroenterology. 1986;91(4):825–829. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes S, Gallo G A, Trash D B, Morris J S. Diagnositic value of serum bile acid estimations in liver disease. J Clin Pathol. 1975;28(6):506–509. doi: 10.1136/jcp.28.6.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter J. Serum bile acids in normal pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98(6):540–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1991.tb10367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glantz A, Marschall H U, Mattsson L A. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Relationships between bile acid levels and fetal complication rates. Hepatology. 2004;40(2):467–474. doi: 10.1002/hep.20336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong L FA, Shallow H, O'Connell M P. Comparative study on the outcome of obstetric cholestasis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21(5):327–330. doi: 10.1080/14767050802034446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmed K T, Almashhrawi A A, Rahman R N, Hammoud G M, Ibdah J A. Liver diseases in pregnancy: diseases unique to pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(43):7639–7646. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i43.7639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brites D, Rodrigues C M, van-Zeller H, Brito A, Silva R. Relevance of serum bile acid profile in the diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy in an high incidence area: Portugal. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;80(1):31–38. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palma J, Reyes H, Ribalta J. et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid in the treatment of cholestasis of pregnancy: a randomized, double-blind study controlled with placebo. J Hepatol. 1997;27(6):1022–1028. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abbassi-Ghanavati M, Greer L G, Cunningham F G. Pregnancy and laboratory studies: a reference table for clinicians. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1326–1331. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c2bde8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fulton I C, Douglas J G, Hutchon D JR, Beckett G J. Is normal pregnancy cholestatic? Clin Chim Acta. 1983;130(2):171–176. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(83)90114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castaño G, Lucangioli S, Sookoian S. et al. Bile acid profiles by capillary electrophoresis in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;110(4):459–465. doi: 10.1042/CS20050302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heikkinen J. Effect of a standard test meal on serum bile acid levels in healthy nonpregnant and pregnant women and in patients with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Ann Clin Res. 1983;15(5-6):183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laatikainen T, Ikonen E. Serum bile acids in cholestasis of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1977;50(3):313–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]