Abstract

Background Though rare, myocardial infarction secondary to coronary artery dissection is a life-threatening event. In reproductive age women, it commonly occurs during pregnancy or the postpartum period.

Case We present a case of pregnancy-related acute myocardial infarction due to spontaneous coronary artery dissection in a 37-year-old woman who presented to the emergency room with shortness of breath and sudden onset of retrosternal chest pain 8 days after delivery of premature twins. Coronary artery catheterization showed 75 to 90% stenosis in the left main coronary artery (LMCA), extending into the proximal and mid left anterior descending (LAD) branch. The LMCA appearance in the heart catheterization was consistent with vasospasm, but it was not responsive to medical management. Subsequently, she underwent a second coronary artery catheterization and was found to have dissection requiring emergent coronary artery bypass graft × 3 in the LMCA, circumflex, and LAD that was followed by an uneventful recovery.

Conclusion Early diagnosis and management of myocardial infarction due to coronary artery dissection in the peripartum period is crucial. This condition should be suspected in young reproductive age women, even in the setting of minimal risk factors. Angiography is required for diagnosis. Management should be individualized as it may include both invasive and noninvasive measures.

Keywords: acute myocardial infarction, coronary artery dissection, reproductive age, peripartum period

Cardiac disease is the leading cause of mortality in pregnancy, and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) accounts for a large proportion (20%) of it.1 It has a significant contribution not only to maternal mortality, but to maternal and fetal morbidity as well.1 2 3 In a large population-based study in the United States, the estimated incidence of pregnancy-related AMI was 6.2 per 100,000 deliveries. In addition, the risk of AMI appears to be approximately three to fourfold higher in pregnant as compared with nonpregnant reproductive age women.2 Moreover, 25% of the cases of AMI during pregnancy or the postpartum period are due to spontaneous coronary artery dissection. In contrast, in nonpregnant women it is only responsible for < 1%.4 This risk varies according to age, race, ethnicity, and parity.2 5 The highest risk of AMI is among black women older than 35 years. For white women aged 35 years and older, the odds of having an AMI is five times higher than for their younger counterpart.2 Complications of pregnancy that are significantly associated with AMI are preeclampsia, postpartum hemorrhage, transfusion, postpartum infection as well as fluid and electrolyte imbalances.2 AMI can occur at any stage in pregnancy and more common in multigravidas. The vast majority of MI involves the anterior wall (78%).6 The most common coronary artery affected is the left anterior descending (LAD) branch.7 Coronary dissection is the primary cause of infarction in the peripartum period and more commonly in the postpartum period.6 As shown in the case we are presenting, the real clinical challenge in sudden coronary artery dissection is related to the need for high suspicion, diagnostic difficulty as well as limited treatment options.

Case Study

A 37-year-old Caucasian multigravida, with a negative medical history except for smoking half a pack per week for more than 20 years, initially presented to a local hospital 8 days after cesarean delivery of twins at 35 weeks gestation with a complaint of shortness of breath and lower extremity swelling. Her antepartum course and delivery were uncomplicated. Her immediate postpartum course was complicated by episodes of chest pain that were not brought to medical attention. Electrocardiogram (ECG) at the time of initial presentation showed a normal sinus rhythm and inconclusive ST-segment changes with possible elevation in the inferior leads. At initial presentation, troponin T was less than 0.2 ng/mL (normal < 0.01 ng/mL) and serum creatinine kinase (CK-MB) was 1.9 ng/mL (female < 3.8 ng/mL). The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for monitoring secondary to suspected postpartum cardiac event or cardiomyopathy. Serial CK-MB and troponins were ordered as well as a two-dimensional echocardiogram that showed normal systolic and diastolic function. Eventually, the diagnosis was volume overload with no evidence of MI. Furosemide and daily aspirin were the mainstay of in-patient treatment. The patient was subsequently discharged home off meds as she was clinically improving.

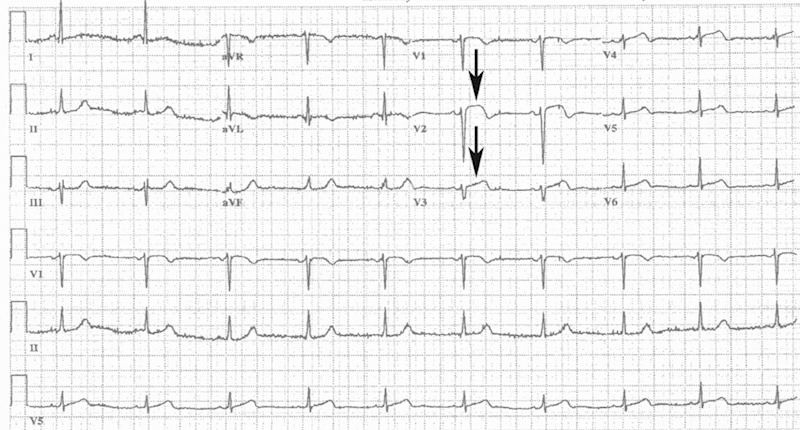

After 3 days she returned to the emergency room (ER) with sudden onset retrosternal chest pain at rest that lasted for 0.5 hour. On evaluation, her vital signs were within normal limits and O2 saturation ranged between 98 and 100%. A 12-lead ECG showed ST-segment elevation in the anterior leads indicating AMI (Fig. 1) for which she was hospitalized. Initial troponin T values were elevated at 1.72 ng/mL, and repeat values were 3.50 ng/mL, and 2.59 ng/mL (normal < 0.01 ng/mL). Her lipid panel showed a cholesterol of 207 mg/dL, triglyceride of 213 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein of 43 mg/dL, and low-density lipoprotein of 121 mg/dL. The complete blood cell count was within normal limits. Finger stick blood sugar was 132 mg/dL. The urine drug screen test was negative except opiates that she had received in the ER.

Fig. 1.

Emergency department Electrocardiogram demonstrating sinus bradycardia and evolving anterolateral ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Arrows depict the ST-elevation.

Acute coronary syndrome protocol was initiated, and she underwent emergency cardiac catheterization revealing a narrowing of the left main coronary artery (LMCA) with extension to the proximal and mid LAD, producing 75 to 90% stenosis. This had the appearance of vasospasm; however, it was unresponsive to intracoronary injections of nitroglycerin, verapamil, and adenosine. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed anterior wall hypokinesis of the left ventricle with left ventricular ejection fraction of 45 to 50%. The patient was accordingly transferred to our cardiac critical care unit (CCU) for further evaluation and management.

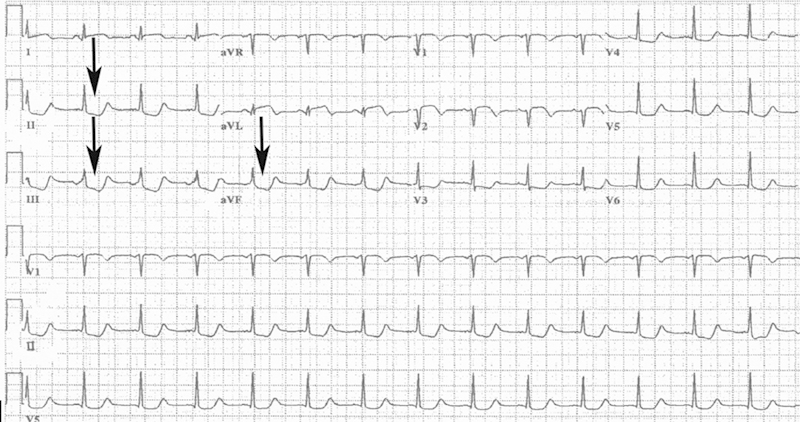

Upon admission to the CCU, the ECG showed ST-segments depression in the inferior leads (II, III, and AVF), ST-segment elevation in the lateral leads, and prolonged QT interval. (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

The 12 lead electrocardiogram demonstrating ST-depression in inferior leads (II, III, and AVF). Arrows depict the ST-depression in inferior leads (II, III, and AVF).

The patient was chest-pain free on a nitroglycerin drip; however, the symptoms recurred as soon as the vasodilator was weaned down. She then underwent another cardiac catheterization with intravenous ultrasound which revealed coronary artery dissection (Fig. 3). She was then taken to the operating room for an emergent three-vessel coronary artery bypass of the LMCA, circumflex, and LAD. An intraoperative transesophageal echocardiogram showed the left ventricle to be normal in size with a mildly reduced systolic function, as well as hypokinesis of the left ventricular septum. The left ventricular ejection fraction was 45 to 50%.

Fig. 3.

Coronary angiogram showing dissection of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery.

Postoperatively, the patient was taken to the CCU in a critical but stable condition for further care and monitoring. Her pain was controlled on intravenous and oral narcotics after she was tolerating her diet. Her three chest tubes remained in place for 2 days after bypass surgery. A control chest X-ray was performed, and the tubes were removed without complications. The patient was transferred to the cardiovascular intermediate care unit for physical and occupational therapy, as well as for strength and endurance training. She was getting out of bed to chair three times a day without any difficulty and was tolerating oral diet. In addition, her pain was well controlled. Following that, the patient was discharged safely to her home with follow-up and a close monitoring. Discharge medications included baby aspirin, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, β blockers, and statins.

Comment

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection in the peripartum period is a rare but life-threatening event. Several explanations have been proposed for the pathogenesis of pregnancy-related spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Hormonal and hemodynamic changes during the peripartum period have been suggested as predisposing factors for acute coronary artery dissection.8 9 10 Female smokers are reported to have a twofold increase in the risk of MI. Our patient was smoking for more than 20 years. Some studies showed that increased level of estrogen and progesterone in pregnancy may compound the risk of AMI among women who smoke.2 The high risk group for atherosclerotic MI in pregnancy is women of 35 years of age or older with a risk factor be it smoking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or diabetes.2 6 11 In younger women, MI is mostly embolic in etiology and more related to structural heart disease than classic cardiac risk factors.11 Pregnancy-related coronary artery dissection is not typically associated with classic coronary disease risk factors (e.g., smoking, arterial hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and so on) but mostly related to the changes in the arterial wall composition such as collagen damage and fragmentation of reticular fibers with simultaneously increased cardiac output (up to 50% during pregnancy).5 10 12 Coronary artery spasm and coronary artery dissection can also be caused by cocaine use.7 Thus, patients with history of substance abuse with any complaint of chest pain should be screened. In this case, the combination of advanced maternal age and hormonal changes during pregnancy in addition to her history of smoking is the most likely etiology for this patient's AMI secondary to coronary artery dissection.

Management of coronary artery dissection should be individualized to the patient's presentation and acuity. For hemodynamically stable patients with lesions in distal branches of coronary arteries and single-vessel disease, medical treatment is the best choice. In stable hemodynamic status in proximal large trunk coronary lesions, which is anatomically accessible to stenting, percutaneous coronary artery intervention is the best treatment. In patients with unstable hemodynamics, multiple vessel involvement or LMCA dissection the recommendation is to proceed to coronary artery bypass graft.4 7 8 Most of the studies discourage thrombolysis due to the risk of extension of a coronary hematoma and worsening of any coronary spasm by compressing the vascular lumen.7 9

In conclusion, the diagnosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection in the peripartum period in young women with minimal risk factors for MI is challenging, and can lead to delays in providing appropriate management. It is important to consider this diagnosis in women who present with signs and symptoms of acute coronary syndrome during pregnancy or postpartum. Management depends on the clinical picture and hemodynamic stability of the patient and requires a multidisciplinary team approach.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors did not report any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bush N Nelson-Piercy C Spark P Kurinczuk J J Brocklehurst P Knight M; UKOSS. Myocardial infarction in pregnancy and postpartum in the UK Eur J Prev Cardiol 201320112–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.James A H, Jamison M G, Biswas M S, Brancazio L R, Swamy G K, Myers E R. Acute myocardial infarction in pregnancy: a United States population-based study. Circulation. 2006;113(12):1564–1571. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.576751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poh C L, Lee C H. Acute myocardial infarction in pregnant women. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39(3):247–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins G L III, Borofsky J S, Irish C B, Cochran T S, Strout T D. Spontaneous peripartum coronary artery dissection presentation and outcome. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(1):82–89. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2013.01.120019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiff J H, Gries A, Ehehalt R, Elsaesser M, Katus H A, Meyer F J. A pregnant woman with acute myocardial infarction due to coronary artery dissection: pre-hospital and in-hospital management. Resuscitation. 2007;73(3):467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roth A, Elkayam U. Acute myocardial infarction associated with pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(3):171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahzad K, Cao L, Ain Q T, Waddy J, Khan N, Nekkanti R. Postpartum spontaneous dissection of the first obtuse marginal branch of the left circumflex coronary artery causing acute coronary syndrome: a case report and literature review. J Med Case Reports. 2013;7:82. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Julià I, Tauron M, Muñoz-Guijosa C. Postpartum acute coronary syndrome due to intramural hematoma and coronary artery dissection. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;61(1):85–87. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1331152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brantley H P, Cabarrus B R, Movahed A. Spontaneous multiarterial dissection immediately after childbirth. Tex Heart Inst J. 2012;39(5):683–686. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cenkowski M, daSilva M, Bordun K A, Hussain F, Kirkpatrick I D, Jassal D S. Spontaneous dissection of the coronary and vertebral arteries post-partum: case report and review of the literature. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:122. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janion M, Sielski J, Janion-Sadowska A. Myocardial infarction in pregnant women—case reports. Int J Cardiol. 2007;121(2):207–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.08.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janion-Sadowska A, Sadowski M, Kurzawski J, Zandecki L, Janion M. Pregnancy after acute coronary syndrome: a proposal for patient's management and a literature review. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:957027. doi: 10.1155/2013/957027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]