Abstract

Objective This study aims to determine the clinical outcomes of monochorionic-triamniotic (MT) pregnancies complicated by severe fetofetal transfusion undergoing laser photocoagulation.

Study Design We report two cases of MT triplets complicated by fetofetal transfusion syndrome (FFTS) and a systematic review classifying cases into different subtypes: MT with two donors and one recipient, MT with one donor and two recipients, MT with one donor, one recipient, and one unaffected triplet. The number of neonatal survivors was analyzed based on this classification as well as Quintero staging.

Results A total of 26 cases of MT triples complicated by FFTS were analyzed. In 56% of the cases, the FFTS involved all three triplets, 50% of whom had an additional donor and 50% an additional recipient. Among the 24 cases that survived beyond 1 week after the procedure, the average gestational age of delivery was 29.6 weeks, and the average interval from procedure to delivery was 10.1 weeks. The overall neonatal survival rate was 71.7%, with demises occurring equally between donor and recipient triplets. Overall neonatal survival including survival of at least two fetuses occurred with equal frequency between the different groups.

Conclusion Significant neonatal survival can be achieved in most cases of MT triplets with FFTS.

Keywords: fetofetal transfusion, monochorionic, triplets, laser, photocoagulation

In the United States, triplets and higher order multiple gestations occur in approximately 153 per 100,000 live births.1 2 Trichorionic placentation occurs in about 42% of the cases, dichorionic in 42%, and monochorionic in only 16% of triplet gestations. Thus, monochorionic triplet gestations are exceedingly rare, occurring presumably in approximately 1.6:100,000 pregnancies.3 Among all triplets, monochorionic-triamniotic triplets are at a significantly higher risk of intrauterine fetal death and neonatal death compared with their trichorionic and dichorionic counterparts.4 Fetofetal transfusion syndrome (FFTS) has been described in both dichorionic and monochorionic triplet gestations, but the majority of published cases describe experience with dichorionic-triamniotic triplets.

In cases of monochorionic-triamniotic triplets complicated by FFTS, different pathological subtypes may be seen including two donor triplets and one recipient triplet, one donor triplet, and two recipient triplets, or one donor triplet and one recipient triplet with an unaffected triplet. It is presumed that different types of placental anastomoses lead to these different clinical subtypes and result in different clinical outcomes. The aim of the study was to determine neonatal survival rates in monochorionic-triamniotic triplet pregnancies complicated by severe FFTS. In addition, we aimed to determine whether neonatal survival rates differ by the number of fetuses involved, as well as by Quintero staging before the procedure.

Methods

We report two cases of monochorionic-triamniotic triplet pregnancies complicated by FFTS that underwent fetoscopic laser ablation in our centers. In addition, a systematic review of the literature was performed in accordance to the STROBE/MOOSE guidelines.5 6 Two of the authors (Y. J. B., R. R.), independently completed literature searches in PubMed, Ovid, and MEDLINE for articles related to fetoscopic laser ablation of placental anastomoses in monochorionic-triamniotic triplets complicated by early onset FFTS and reference lists of selected articles was performed to find relevant articles. The reference list of the articles identified was examined for potential additional pertinent references. The following terms were used: “triplets,” “fetofetal,” “feto-fetal,” “monochorionic,” and “laser.” Of all citations identified in the original search, we reviewed data detailing experience with laser photocoagulation of the communicating placental vessels in cases of FFTS complicating monochorionic-triamniotic triplet gestations. Articles were included in the review if they were published in English in the past 10 years (2004–2014). We chose to include only those published in the past 10 years because we wanted to limit the data to those originating in centers where the learning curve of laser photocoagulation as a therapeutic option likely occurred. Ten publications, both case series and case reports, in addition to our cases were included in the final analysis.

Articles included in the analysis detailed experience limited to a single case report up to a case series of six monochorionic-triamniotic triplets. Reported cases were then classified into different subtypes: monochorionic-triamniotic pregnancy with two donors and one recipient triplet (MT-DDR), monochorionic-triamniotic pregnancy with one donor triplet and two recipient triplets (MT-DRR), and monochorionic-triamniotic pregnancy with one donor triplet, one recipient triplet, and one unaffected triplet (MT-DRx). Clinical outcomes including the average gestational age of the procedure, the average gestational age of delivery, Quintero staging, and overall neonatal survival (0, 1, 2, and 3 survivors) were compared between the three groups.7 Differences in categorical outcomes between groups were analyzed using Fisher exact test, and differences between the means were compared using one-way analysis of variance. Statistical difference was considered when p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

Results

Case Report

Case 1

The patient was a 35-year-old gravida 3, para 2 with monochorionic-triamniotic triplets conceived via in vitro fertilization. Her medical history was significant for mild chronic hypertension that did not require antihypertensive therapy, and her surgical history was unremarkable. She underwent serial ultrasound surveillance starting at 16 weeks and at 19 weeks gestation was diagnosed with stage 2 FFTS based on Quintero staging, with triplet A serving as the primary recipient with increased amniotic fluid level (deepest vertical pocket, DVP = 12.3 cm) and an enlarged bladder size, and triplet C serving as the primary donor with oligohydramnios and a nonvisualized bladder. Triplet B appeared uninvolved with normal fluid level and bladder size. The placenta was posterior, triplet A appeared to have a velamentous cord insertion, and triplets B and C had central cord insertions. All Doppler indices including the umbilical artery (UA), umbilical vein (UV), middle cerebral artery (MCA), and ductus venosus (DV) appeared within normal limits in all triplets. The patient initially underwent an amnioreduction procedure of triplet A's amniotic sac. Unfortunately, the polyhydramnios in triplet A recurred rapidly, and at 21 weeks gestation she was diagnosed with Quintero stage 3 FFTS with polyhydramnios (DVP = 11.7 cm.), along with an increased bladder size and reversed a-wave Doppler pattern in the DV seen in triplet A. Triplet C had become stuck with a nonvisualized bladder, and elevated S/D ratio in the UA. Of note, triplet B (located between triplets A and C) that initially appeared uninvolved now had increased amniotic fluid (DVP 12.9 cm) with normal Doppler indices of all vessels.

After extensive prenatal counseling, the patient underwent laser photocoagulation of the placental anastomosing vessels between triplet A and the adjacent triplets B and C. Because of the severe oligohydramnios in triplet C and the position of the sacs, laser photocoagulation could not be performed between C and B. In total, seven anastomosing vessels were coagulated using a single port insertion in the sac of triplet A, solomonization was performed between triplet A and its adjacent triplets, and 1,100 mL of amniotic fluid was removed from the sac of triplet A at the end of the procedure.

The patient recovered well from the procedure in the immediate postoperative period. However, triplet B developed significant cord edema and skin edema within the first 24 hours after the procedure that persisted for several days. The oligohydramnios/polyhydramnios findings resolved with normal-appearing bladders and Doppler studies in both triplets A and C. Serial growth ultrasound assessments showed appropriate growth of triplets C and B, however triplet A's growth began to lag behind its cotriplets, measuring 14% for gestational age over the course of several ultrasound examinations postprocedure. At 28 weeks gestation, the patient was admitted with preterm labor for tocolysis and betamethasone course. Within 12 hours of admission, severe fetal heart rate decelerations were noted, and an emergency cesarean delivery was performed. Magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection was administered before delivery.

Triplet A weighed 820 g with Apgar scores of 3 and 8 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. He required positive pressure ventilation to initiate spontaneous respirations, was intubated for surfactant administration, and extubated to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) at several hours of life. He developed a spontaneous intestinal perforation of the sigmoid colon on day of life 4, requiring eventual colostomy on day 12. Serial ultrasounds in the first 2 weeks of life were negative for intraventricular hemorrhage. At approximately 3 weeks of age, he developed clinical seizures attributed to multifocal ischemic infarcts on brain magnetic resonance imaging, possibly attributed to a line-associated thrombus in the inferior vena cava. Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) ligation was performed on day 30 for worsening respiratory failure. He was discharged on day 85, on full oral feeds, weighing 2,607 g. He required supplemental oxygen at discharge due to chronic lung disease and prethreshold retinopathy of prematurity.

Triplet B weighed 1,150 g with Apgar scores of 6 and 8 at 1 and 5 minutes of life, respectively. He initially required CPAP support in the delivery room but was later intubated for surfactant administration. PDA ligation was performed on day 40. Serial head ultrasounds were normal and showed no evidence of hemorrhage. He was discharged home on day of life 78, weighing 2,704 g, and full oral feeds.

Triplet C weighed 1,030 g with Apgar scores of 3 at 1 minute and 7 at 5 minutes of life. He required brief positive pressure ventilation at delivery and was then stabilized on CPAP. He had mild respiratory distress syndrome, requiring intubation for surfactant and respiratory support until 37+2 weeks postmenstrual age. PDA closed with conservative management. Serial head ultrasounds were performed and showed no evidence of hemorrhage. He was discharged home on day of life 76 on full oral feeds, weighing 2,568 g.

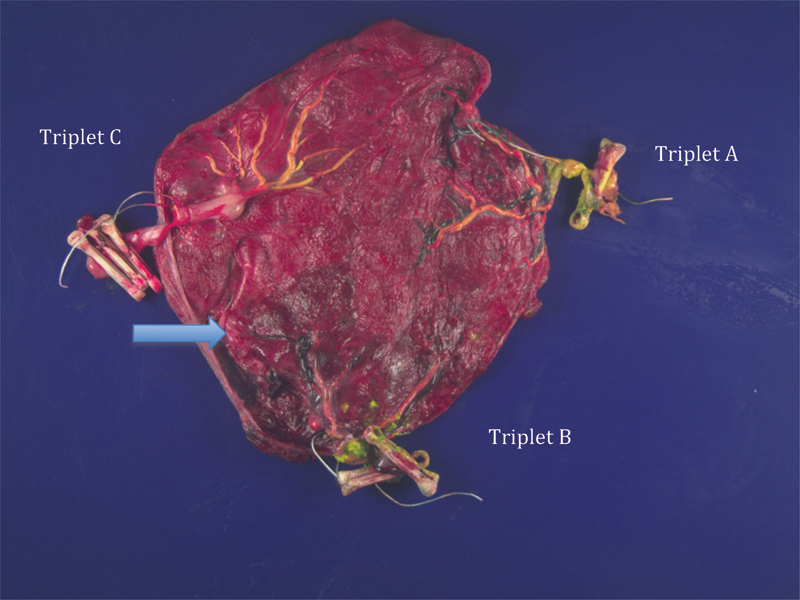

Pathological examination of the placenta revealed a monochorionic-triamniotic placenta with no vascular connections between triplets A and C, but some connections between A and B (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Gross examination of the placenta. The fetal amniotic membranes have been removed and the vessels injected with dye. Triplet A is shown on the right with a velamentous cord insertion and a single cord clamp. Triplet B is on the bottom with two clamps and triplet C is on the left with three clamps. Connections are still visible between the cords of triplets B and C (small arrow) whereas no connections are visible between triplet A and the cotriplets.

Case 2

A 30-year-old gravida 4, para 1, with monochorionic-triamniotic triplet pregnancy was referred at 19 1/7 weeks gestation with stage 4 FFTS based on Quintero staging. The patient's medical history was significant for well-controlled chronic hypertension for 1 year before the current pregnancy. Initial ultrasound evaluation revealed one recipient and two donor fetuses. The recipient fetus had polyhydramnios (DVP = 9.4 cm.) with hydrops (moderate ascites, skin and scalp edema) and the fetal heart had poor contractility with episodes of bradycardia and severe tricuspid regurgitation. The fetal bladder was enlarged and Doppler studies revealed normal blood flow in the UA and MCA but there was a reverse a-wave in the DV and a pulsatile wave in the UV. The placental umbilical cord insertion was velamentous adjacent to an anterior placenta. Both donors (D1 and D2) were noted to have oligohydramnios (D1 was stuck but D2 was not), with no signs of hydrops and both had very small fetal bladders. Doppler studies revealed normal flow patterns in the UA, MCA, DV, and UV of both fetuses. Fetal echocardiography revealed normal cardiac function in both donor fetuses.

Due to the complete anterior placenta with no window for ultrasound-guided fetoscopy and the position of both donors, a laparoscopic-assisted fetoscopic laser ablation procedure was performed at 19 1/7 weeks gestation. The fetoscope was inserted into the recipient triplet's sac, and all the anastomoses between recipient and both donors were successfully coagulated followed by solomonization. Using the same uterine puncture from the recipient's sac, the anastomoses between the two donor triplets were identified over the floating membranes and then coagulated, but a complete solomonization between the donor triplets was not possible due to floating membranes. Amnioreduction of 900 mL was removed from the recipient triplet.

The patient recovered well postoperatively, however on postoperative day 6, echocardiography showed severely depressed systolic and diastolic cardiac function in the ex-recipient fetus. There was mild improvement in the fetal hydrops in the ex-recipient with normal fetal bladder size and amniotic fluid volume, but persistent reversed a-wave in the DV. All ultrasound parameters appeared within normal limits in both ex-donors.

After 2 weeks of the procedure, Doppler studies revealed elevated peak systolic velocity (PSV) in the MCA of the ex-recipient (2.20 MoM) and ex-donor 1 (1.95 MoM), in contrast with low MCA PSV in the ex-donor 2 (0.74 MoM), consistent with Twin Anemia-Polycythemia Sequence (TAPS). At 24 5/7 weeks gestation, demise of the ex-recipient was noted. Initially, echocardiography showed stable cardiac findings in the remaining ex-donor triplets and expectant management was continued until 26 1/7 weeks gestation. At that time persistent TAPS was noted between the ex-donor 1, with MCA PSV of 2.4 MoM, and the ex-donor 2 with decreased MCA PSV of 0.67 MoM (stage 2 TAPS). Both fetuses were noted to have significant variable decelerations with the ex-donor 1 showing prolonged periods of tachycardia. In view of the worrisome fetal heart rate tracings and following a detailed multidisciplinary discussion with the family and the neonatology teams, the patient was offered immediate delivery versus expectant management versus exchange transfusion. The family elected to undergo an exchange transfusion in an attempt to increase the gestational age before delivery.

Ex-donor 2 (now the primary recipient of the TAPS) had significant polycythemia with hematocrit (hct) of 61% that decreased to 47% after removing 21 mL blood and replacement with saline. An IP transfusion was performed in ex-donor 1 (now the primary donor in the TAPS) with a total of 15 mL infused into the donor's abdomen. However, the patient underwent cesarean delivery on postoperative day 2 (26 3/7 weeks gestation) due to nonreassuring fetal status of the ex-donor 2 triplet.

The ex-donor 1 weighed 640 g, and had Apgar scores of 3 and 7 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. His hemoglobin (Hb) concentration was 4.4 g/dL (hct 13.6%). The ex-donor 2 weighed 941 g, had Apgar scores of 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively, and a Hb concentration of 19.4 g/dL (hct 54.7%) which confirmed the TAPS. Placental examination revealed fetal thrombotic vasculopathy between ex-donors 1 and 2, which may be associated with the abnormal cord insertions that existed in donor 1's placental segment. Residual chorionic plate vessels were seen between donors 1 and 2 placental areas. Also, microscopic studies showed diffuse placenta accreta which was far greater than usually seen as an incidental microscopic finding.

The neonatal period of donor 1 was complicated by anemia, necrotizing enterocolitis, peritonitis, intraventricular hemorrhage (grade IV), bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and acute kidney injury. The neonatal period of donor 2 was unremarkable.

Systematic Data Review

Following a systematic review of published data, 24 cases of monochorionic-triamniotic triplets complicated by FFTS were reported in the literature and 2 additional cases were managed in our centers (Table 1). Thus, a total of 26 cases of laser photocoagulation in monochorionic-triamniotic triplet gestations with fetofetal transfusion detailing the outcomes of 78 total triplets were included in the analysis. One case did not describe the number of donor and recipient triplets involved in the FFTS,8 and three of the cases did not describe the Quintero stage before the procedure.9 Mean gestational age at fetoscopic laser ablation was 19.4 ± 2.1 weeks and mean gestational age of delivery for the entire cohort was 28.8 ± 4.1 weeks. Among the cases that outlined the number of fetuses involved in the FFTS, in 56% of the cases, the FFTS involved all three triplets, 50% of whom had an additional donor third triplet and 50% an additional recipient third triplet. Two of the 26 cases (7.7%) resulted in demise of the entire pregnancy within 1 week of the procedure. Among the cases that survived beyond 1 week after the procedure, the average gestational age of delivery was 29.6 weeks gestation, and the average interval from procedure to delivery was 10.1 weeks.

Table 1. Case series of monochorionic-triamniotic triplets with fetofetal transfusion.

| Case | Author | Year | TTTS Quintero stage | FFTS type | GA at laser (wk) | GA at delivery (wk) | Procedure to delivery interval (wk) | Outcome fetus 1 | Outcome fetus 2 | Outcome fetus 3 | Overall neonatal survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Van Schoubroecka | 2004 | 3 | 19 | 30 | 11 | A&W | A&W | A&W | 3 | |

| 2 | Sepulveda | 2005 | DRx | 17 | 18 | 1 | Demise 18 (D) | Demise 18 (R) | Demise 18 (U) | 0 | |

| 3 | Sepulveda | 2005 | DRx | 23 | 34 | 11 | Demise 25 (D) | A&W 34 (R) | Demise 25 (U) | 1 | |

| 4 | Sepulveda | 2005 | DDR | 19 | 28 | 11 | Demise 21 (D) | Demise 23 (R) | A (NDD) (D) | 1 | |

| 5 | Ishii | 2006 | 3 | DRR | 19 | 31.7 | 12.7 | Demise 19 (D) | Demise 19 (R) | A (PVL) (R) | 1 |

| 6 | De Lia | 2009 | 4 | DDR | 19.5 | 32 | 12.5 | A&W (D) | A&W (R) | A&W (D) | 3 |

| 7 | Diemert | 2010 | 2 | DRR | 18 | 26.6 | 8.6 | A&W (D) | A (IVH) (R) | A&W (R) | 3 |

| 8 | Deimert | 2010 | 3 | DDR | 19.6 | 32 | 12.4 | A&W (D) | A&W (D) | Demise (R) | 2 |

| 9 | Chmait | 2010 | 1 | DRR | 21.1 | 26.7 | 5.6 | Demise (D) | A&W (R) | A&W (R) | 2 |

| 10 | Chmait | 2010 | 2 | DDR | 19.9 | 35.1 | 15.2 | A&W (D) | A&W (R) | A&W (clubfoot) (D) | 3 |

| 11 | Chmait | 2010 | 1 | DRx | 19.6 | 28.4 | 8.8 | A&W (D) | A (VP shunt) (R) | A&W (U) | 3 |

| 12 | Chmait | 2010 | 4 | DRx | 19.7 | 19.9 | 0.2 | Demise (D) | Demise (R) | Demise (U) | 0 |

| 13 | Chmait | 2010 | 3 | DRR | 17.7 | 26.4 | 8.7 | Demise (D) | A (BPD, ROP) (R) | Demise (R) | 1 |

| 14 | Chmait | 2010 | 2 | DRx | 18.6 | 30.6 | 12 | Demise (D) | A&W (R) | A&W (U) | 2 |

| 15 | Shamshirsaz | 2012 | 4 | DDR | 16.3 | 33.1 | 16.8 | A & W (D) | A & W (R) (band syndrome) | A & W (D) | 3 |

| 16 | Peeters | 2012 | 3 | DRR | 15 | 30 | 15 | Demise 22 (D) | Demise 16 (R) | A&W (R) | 1 |

| 17 | Davidoffb | 2013 | 3 | DRx | 24.4 | 26.6 | 2.2 | Demise 24 (D) | A&W (R) | A&W (U) | 2 |

| 18 | Ishii | 2014 | 2 | DRx | 19 | 29 | 10 | A&W (D) | A&W (R) | A&W (U) (amniotic band syndrome) | 3 |

| 19 | Ishii | 2014 | 3 | DDR | 22 | 34 | 12 | Demise (D) | A&W (R) | A&W (D) | 2 |

| 20 | Ishii | 2014 | 4 | DDR | 18 | 29 | 11 | A&W (D) | A&W (R) | A&W (D) | 3 |

| 21 | Ishii | 2014 | 3 | DRx | 22 | 31 | 9 | A&W (D) | A&W (R) | A&W (U) | 3 |

| 22 | Ishii | 2014 | 2 | DRx | 20 | 28 | 8 | A&W (D) | A (IVH 3) (R) | A&W (U) | 3 |

| 23 | Ishii | 2014 | 2 | DRR | 20 | 32 | 12 | A&W (D) | A&W (R) | A&W (R) | 3 |

| 24 | Ishii | 2014 | 3 | DRx | 17 | 23 | 6 | A&W (D) | A&W (R) | A (IVH 4) (U) | 3 |

| 25 | Current case 1 | 2013 | 3 | DRx | 21 | 28 | 7 | A&W (D) | A (CLD, ischemic brain injury) (R) | A&W (U) | 3 |

| 26 | Current case 2 | 2013 | 4 | DDR | 19.1 | 26.1 | 7 | (D) IVH4, NEC, BPD | Demise 26 (R) | A&W (D) | 2 |

| Total: 26 cases | Avg: 19.4 ± 2.1 wk | Avg: 28.8 ± 4.1 wk | Avg: 9.4 wk | 56/78 (71.7%) | |||||||

Abbreviations: Avg, average; A&W, alive and well; DDR, pregnancy with two donors and one recipient triplet; DRR, pregnancy with one donor triplet and two recipient triplets; DRx, pregnancy with one donor triplet, one recipient triplet, and one unaffected triplet.

Notes: The gestational ages of the demise are indicated when reported by the authors. Neonatal survival as reported the authors.

(D), (R), and (U) represents the donor, recipient, and unaffected triplet when indicated by the authors.

The order of the triplets shown in the table lists the donor in the first column and recipient in the second, irrespective of the way the triplets were listed in the original articles.

Case-specified one recipient and two donors.

Complicated by TAPS postlaser.

The overall neonatal survival rate to discharge for the cohort was 72%. Fetal and neonatal demises occurred equally in the donor triplets compared with the recipient triplets (11/33 donors vs. 8/31 recipients, p = 0.59). In 2 cases (7.7%) there were no neonatal survivors, in 5 cases (19.2%) 1 survivor, 6 cases (23.0%) 2 survivors, and 13 cases (50.0%) all three triplets survived.

When classifying the cases by number of donor and recipient fetuses, 8 (32.0%) patients had MT-DDR FFTS, 6 cases (24.0%) had MT-DRR subtype, and 11 (44.0%) cases had MT-DRx subtype. Table 2 demonstrates the characteristics and outcomes according to the subtype of FFTS in monochorionic-triamniotic triplets. There were no differences between the groups in regards to gestational age of procedure, gestational age of delivery, Quintero stating, or neonatal survival between the two groups.

Table 2. Characteristics and outcome in monochorionic-triamniotic triplets with fetofetal transfusion syndrome that underwent fetoscopic laser ablation.

| MT-DDR (n = 8) | MT-DRR (n = 6) | MT-DRx (n = 11) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at surgery (wks), mean ± standard deviation | 19.2 ± 1.6 | 18.5 ± 2.1 | 20.1 ± 2.3 | 0.46 |

| I | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.46 |

| II | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| III | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| IV | 4 | 0 | 1 | |

| Gestational age at delivery (wk), mean ± standard deviation | 31.2 ± 3.1 | 28.9 ± 2.6 | 26.9 ± 4.8 | 0.17 |

| Survivors | ||||

| 0 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (18.2%) | 0.63 |

| 1 | 1 (12.5%) | 3 (50.0%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| 2 | 3 (37.5%) | 1 (16.6%) | 2 (18.2%) | |

| 3 | 4 (50.0%) | 2 (33.3%) | 6 (54.5%) | |

| At least two survivors | 7 (88%) | 3 (50%) | 8 (73%) | 0.51 |

Abbreviations: DDR, pregnancy with two donors and one recipient triplet; DRR, pregnancy with one donor triplet and two recipient triplets; DRx, pregnancy with one donor triplet, one recipient triplet, and one unaffected triplet; MT, monochorionic-triamniotic.

Discussion

FFTS may occur in 5% of dichorionic triplets, and in approximately 8% of monochorionic triplets.4 10 Unfortunately, data describing the benefits and risks of laser photocoagulation in monochorionic triplets with fetofetal transfusion has been limited to case report and small case series.8 9 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Here, we describe two additional cases of monochorionic-triamniotic triplets with severe fetofetal transfusion (Quintero stages 3 and 4, respectively) that underwent laser photocoagulation of the communicating placental vessels before 22 weeks gestation.

In our experience neonatal survival occurred in all triplets in the first patient and in two triplets in the second patient, though both cases delivered extremely prematurely at 28 and 26 weeks gestation. Our systematic review revealed an average gestational age of 28.8 weeks after fetoscopic laser coagulation of placental anastomoses in monochorionic-triamniotic pregnancies complicated with FFTS which is about 9 weeks from the initial procedure, thus converting a likely demise of all triplets at 21 to 24 weeks into potential survivors albeit preterm. The average gestational age at delivery among monochorionic triplets is in stark contrast to the average delivery timing (32–33 weeks gestation) reported with both uncomplicated triplet gestations, and monochorionic-diamniotic twins undergoing laser photocoagulation for severe twin–twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS), but similar to dichorionic-triamniotic pregnancies with FFTS.1 19 20 A study comparing outcomes of laser photocoagulation in 16 dichorionic triplet gestations with 32 monochorionic twins found a similar early gestational age at delivery among dichorionic triplets, with a mean gestational age of delivery of 28.5 weeks compared with 31.9 weeks for their twin counterparts (p = 0.02).20

In addition to fetal and neonatal demise, there are important complications to consider when counseling patients with monochorionic-triamniotic triplets with FFTS. Reported complications include preterm premature membrane rupture (PPROM), placental separation, twin anemia-polycythemia sequence (TAPS), intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and pseudoamniotic band syndrome, although it is difficult to make definitive conclusions regarding the frequency of such complications. Among our cases the first was complicated by spontaneous preterm labor and borderline IUGR of the recipient twin, while the second patient was complicated by TAPS. The severe prematurity is associated with complications including stage 3 and 4 intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), and periventricular leukomalacia (PVL). Longer-term neonatal outcome data including neurodevelopmental outcome data unfortunately are still lacking, and further studies in these cohorts are warranted.

TAPS complicated one of our patients after fetoscopic laser of placental anastomoses and has been described in other cases of monochorionic triplets undergoing laser photocoagulation.15 Solomonization of the placental vascular connections has been described as a method of reducing post-procedure TAPS in monochorionic triplets.21 22 Solomonization may be more challenging in triplets, particularly those with DDR and DRR physiology due to the difficulty in accessing all amniotic sacs involved.

Compared with twin gestations with TTTS, laser photocoagulation in triplets poses specific technical difficulties including decreased visualization due to multiple sacs, increased risk of membrane separation, and possible need for multiple trocar insertions if an attempt is made to separate all three sacs when more than 2 triplets are involved.16 In our systematic review and meta-analysis 50% of the cases involved all three triplets, the majority of which had two donors. When comparing cases with two versus three triplets involved in the feto-maternal hemorrhage, there does not appear to be a difference in gestational age of delivery, or having 3 survivors.

The precise rates of severe maternal complications from laser photocoagulation in monochorionic-triamniotic triplet gestations including amniotic fluid embolism, hysterectomy, severe hemorrhage, and severe preeclampsia/mirror syndrome remain unknown. Both of our cases resulted in preterm cesarean deliveries with average blood loss and no long-term maternal sequelae. Accurate reporting of neonatal as well as maternal outcome data are warranted in future studies.

Our review is limited by several factors. First, it is possible that additional experience culminating in adverse outcomes was never published, and therefore the cases presented may represent only a subset of the true incidence of outcomes. Second, not all cases included similar fetal and maternal data, and comprehensive assessments of the factors contributing to outcomes such as preterm delivery, fetal and neonatal demise are lacking. Finally, given the limited experience with feto-fetal transfusion in triplet gestation overall, it is possible that the adverse outcomes reported are related to limited technical expertise of the providers rather than the natural history of the disease and therapy. That being said, all of the cases included have come from academic centers with additional publications detailing experience with laser photocoagulation of placental vessels in twin gestations complicated by TTTS. Despite these limitations, our review and meta-analyses represents the largest analysis of published cases of monochorionic-triamniotic triplets undergoing laser photocoagulation of vascular placental anastomoses. In addition, detailing outcomes based on donor versus recipient triplet, and based on whether two or three fetuses were involved can assist providers in counseling patients faced with this rare complication.

In summary, we report on 78 neonatal outcomes from 10 years of published data in monochorionic triplet pregnancies with severe FFTS that underwent fetoscopic laser ablation of placental anastomoses. Given the high perinatal demise risk in cases of early onset FFTS in monochorionic-triamniotic triplets, it appears that laser photocoagulation of communicating anastomoses can lead to significant neonatal survival and although technically more challenging, should be offered to patients willing to undertake the fetal and maternal risks associated with this procedure in such cases. A complete solomonizaton preferably in two consecutive procedures may be optimal to avoid complications such TAPS. However, the rarity of these conditions, the required operator and prenatal diagnostic skills, the variety of management options and the requirement of in-depth counseling of patients currently limit the availability of such interventions to referral centers for fetal intervention. A multicenter registry to assess the risks and benefits of this therapy in triplets is therefore warranted.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose related to this article.

References

- 1.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine . ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 144: Multifetal gestations: twin, triplet, and higher-order multifetal pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):1118–1132. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000446856.51061.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin J A, Hamilton B E, Ventura S J. et al. Births: final data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;60(1):1–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savelli L, Gabrielli S, Pilu G. Two- and three-dimensional sonography of a monochorionic triplet gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;18(6):683–684. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7692.2001.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawaguchi H Ishii K Yamamoto R Hayashi S Mitsuda N; Perinatal Research Network Group in Japan. Perinatal death of triplet pregnancies by chorionicity Am J Obstet Gynecol 20132091360–3.6E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stroup D F, Berlin J A, Morton S C. et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Elm E Altman D G Egger M Pocock S J Gøtzsche P C Vandenbroucke J P; STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies BMJ 20073357624806–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quintero R A, Morales W J, Allen M H, Bornick P W, Johnson P K, Kruger M. Staging of twin-twin transfusion syndrome. J Perinatol. 1999;19(8 Pt 1):550–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Schoubroeck D, Lewi L, Ryan G. et al. Fetoscopic surgery in triplet pregnancies: a multicenter case series. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(5):1529–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sepulveda W, Surerus E, Vandecruys H, Nicolaides K H. Fetofetal transfusion syndrome in triplet pregnancies: outcome after endoscopic laser surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(1):161–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chasen S T, Al-Kouatly H B, Ballabh P, Skupski D W, Chervenak F A. Outcomes of dichorionic triplet pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(4):765–767. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishii K, Murakoshi T, Numata M, Kikuchi A, Takakuwa K, Tanaka K. An experience of laser surgery for feto-fetal transfusion syndrome complicated with unexpected feto-fetal hemorrhage in a case of monochorionic triamniotic triplets. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2006;21(4):339–342. doi: 10.1159/000092462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Lia J E, Worthington D, Carr M H, Graupe M H, Melone P J. Placental laser surgery for severe previable feto-fetal transfusion syndrome in triplet gestation. Am J Perinatol. 2009;26(8):559–564. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1220789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishii K, Nakata M, Wada S, Hayashi S, Murakoshi T, Sago H. Perinatal outcome after laser surgery for triplet gestations with feto-fetal transfusion syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2014;34(8):734–738. doi: 10.1002/pd.4357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chmait R H, Kontopoulos E, Bornick P W, Maitino T, Quintero R A. Triplets with feto-fetal transfusion syndrome treated with laser ablation: the USFetus experience. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23(5):361–365. doi: 10.1080/14767050903177201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidoff D F, Dickinson J E, Warner T, Pennell C E. Twin-twin transfusion syndrome and twin anemia-polycythemia sequence in a monochorionic triamniotic pregnancy. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2013;16(3):716–719. doi: 10.1017/thg.2013.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peeters S H, Middeldorp J M, Lopriore E, Klumper F J, Oepkes D. Monochorionic triplets complicated by fetofetal transfusion syndrome: a case series and review of the literature. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2012;32(4):239–245. doi: 10.1159/000339651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diemert A, Diehl W, Huber A, Glosemeyer P, Hecher K. Laser therapy of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome in triplet pregnancies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35(1):71–74. doi: 10.1002/uog.7328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shamshirsaz A A, Shamshirsaz A A, Nayeri U A, Bahtiyar M O, Belfort M A, Campbell W A. Pseudoamniotic band syndrome: a rare complication of monochorionic triplets with twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(1):97–98. doi: 10.1002/pd.2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senat M V, Deprest J, Boulvain M, Paupe A, Winer N, Ville Y. Endoscopic laser surgery versus serial amnioreduction for severe twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(2):136–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Argoti P S, Papanna R, Bebbington M W. et al. Outcome of fetoscopic laser ablation for twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome in dichorionic-triamniotic triplets compared with monochorionic-diamniotic twins. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;44(5):545–549. doi: 10.1002/uog.13369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruano R, Rodo C, Peiro J L. et al. Fetoscopic laser ablation of placental anastomoses in twin-twin transfusion syndrome using ‘Solomon technique’. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42(4):434–439. doi: 10.1002/uog.12492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slaghekke F, Lopriore E, Lewi L. et al. Fetoscopic laser coagulation of the vascular equator versus selective coagulation for twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9935):2144–2151. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62419-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]