Abstract

Pyrazinamide (PZA) plays a critical role in shortening tuberculosis treatment duration and in treating MDR-TB. The standard phenotypic MGIT PZA susceptibility testing method is imperfect because it is slow and has potential for false resistance. In this study we evaluated two different phenotypic based methods, qPCR phage assay and MTT assay, as well as genotypic sequencing. The assay was evaluated on 71 clinical M. tuberculosis isolates (37 MGIT PZA susceptible, 34 MGIT PZA resistant) and compared to the MGIT result. Of these methods the qPCR phage assay yielded an accuracy of 89% versus standard MGIT while MTT yielded 83%. The genotypic sequencing method yielded 90% accuracy. We conclude that any of these faster PZA susceptibility methods perform reasonably well against a MGIT PZA susceptibility standard.

INTRODUCTION

Pyrazinamide (PZA) is a first-line drug for the treatment of tuberculosis. The importance of PZA susceptibility testing has increased due to the synergistic activity of pyrazinamide amidst new drug regimens, the need for improved MDR-TB combination therapies, and the recognition of PZA monoresistant strains of M. tuberculosis (9). Conventional susceptibility testing for PZA is limited by the requirement for acidic media, its long turnaround time, and the propensity for false resistance using the MGIT method (4, 16, 17). In this study we therefore set out to develop and evaluate new rapid PZA susceptibility methods.

Colorimetric methods using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) indirectly determine viability of mycobacterial cells after exposure to antibiotics. Based on metabolic activity, the yellow MTT dye is reduced by dehydrogenase in living cells to produce purple MTT formazan which can be visualized or quantified by spectrophotometry (10, 18). This method allows a susceptibility result within several days (1, 8, 13). Another rapid method is to measure the viability of mycobacterial cells by measuring D29 mycobacteriophage, which replicates only in living cells and can be quantified by real-time PCR. This qPCR phage assay can be performed in 4 days and can be used for several 1st and 2nd line drugs but also has not been tested for pyrazinamide (2, 7, 14). In this work we developed these two methodologies, MTT and phage. Lastly, genotypic testing of the pncA gene is fast and growing in popularity but correlates with phenotypic PZA results with only approximately 85% accuracy (11, 12, 15) due to both false resistance (pncA mutations in susceptible strains) and false susceptibility (pncA wild-type in resistant strains). In this work we compared each of these methods against the MGIT PZA standard.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycobacterial strains and culture conditions

A total of 71 Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) clinical isolates including 34 PZA resistant and 37 PZA susceptible strains according to the MGIT method, as well as one reference strain H37Rv (ATCC 27294) were obtained from Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand. MTB isolates were cultured on Lowenstein-Jensen medium at 37°C for 2–3 weeks followed by susceptibility testing. Seventy two (51/71) 72% of strains were resistant to Isoniazid and Rifampin (MDR).

Antimicrobial agents

Pyrazinamide (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was dissolved in 2.5 ml of sterile distilled water to make a stock solution of 8000 μg/ml which was stored in single-use aliquots at −20°C for 6 months.

Standard MGIT PZA susceptibility testing

PZA susceptibility tests were carried out in MGIT PZA medium (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, a 0.5 McFarland suspension was diluted 1:5 and 1:50 in sterile distilled water and 500 μl of the 1:50 dilution was inoculated into MGIT PZA medium plus supplement without drug, while the 1:5 dilution was inoculated into MGIT PZA medium plus supplement with 100 μg/ml PZA drug and incubated in MGIT instrument at 37°C. Results were read automatically within 14 days after inoculation of media. M. tuberculosis H37Rv, susceptible to PZA, was used for quality control. The MGIT DST was performed at least twice and only isolates that were resistant or susceptible on both tests were used. Additionally, when we encountered isolates that were discrepant between MGIT and any of the comparator methods (D29 phage, MTT, or sequencing) we performed MGIT a third time and we used the latter results as the final MGIT result.

D29 phage assay

Middlebrook 7H9 (M7H9) broth supplemented with 10% Middlebrook oleic acid-albumin-dextrose catalase (OADC) enrichment (Difco, Livonia, MI, USA) plus 1 mM CaCl2 adjusted pH to 5.9 was used as PZA susceptibility testing medium. The final concentration of PZA was 100 μg/ml as for MGIT (5). All 71 MTB isolates were tested by D29 phage assay using LJ isolates as inoculum as described previously (7) with some modifications. Inoculum suspensions were prepared to 0.5 McFarland standards and diluted 1:10 in adjusted pH M7H9. Fifty microliters of suspension was inoculated into each well of a 96-well plate containing 50 μl of drug-containing, drug-free (pH 5.9), or drug-free (normal pH) medium then incubated at 37°C for 48 h. One hundred microliter of ~2 × 103 PFU/ml D29 phage in M7H9 supplemented with 10% OADC plus 1 mM CaCl2 was added and re-incubated for 48 h. The D29 phage qPCR assay using real-time PCR was performed as described previously (7). The cycle threshold (Ct) of D29 phage alone (Ct of starting phage), the Ct of MTB isolates in drug-free (normal pH) medium followed by phage treatment (Ct of control TB), the Ct of MTB isolates in drug-free (pH 5.9) medium followed by phage treatment (Ct of acid control TB), and the Ct of TB isolates in drug-containing medium followed by phage treatment (Ct of drug TB) were recorded then analyzed.

MTT assay

The MTT assay was performed by adaptation of our in-house MTT assay protocol for isoniazid, rifampicin and ethambutol (8). Briefly, acid adjusted (pH 5.9) M7H9 broth supplemented with 10% OADC enrichment was used as PZA susceptibility testing medium. The PZA critical concentration was prepared as described above. Inoculum suspensions were prepared to 0.5 McFarland standards in adjusted pH M7H9. Fifty microliters of suspension was inoculated into each well of a 96-well plate containing 50 μl of drug-containing, drug-free (pH 5.9) or drug-free (normal pH) medium then incubated at 37°C for 7 to 10 days until visible growth in the drug-free (pH 5.9) medium well (6), then 1 μl of MTT solution (10 μg/ml) was added into each well. The plate was re-incubated for 3 hours and then 100 μl of lysis solution (0.1 HCL in isopropanol) was added then the plate stood at room temperature for 30 min. PZA resistant isolates were defined by the color change from yellow to violet precipitate in both drug-free (pH 5.9) medium and drug-containing wells, while PZA susceptible isolates turned yellow to violet only in drug-free (pH 5.9) medium. When discordant results between the two developed methods (D29 phage and MTT) were found, the isolates were repeated twice for each method and the final result was adjudicated as the result of two of the three tests.

Sequencing of the pncA gene

Two hundred microliters of a 0.5 McFarland suspension was heat inactivated at 100 °C for 30 min then DNA was extracted by QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The pncA gene was amplified using forward and reverse primer of Campbell et al. (3). Each 50-μl PCR mixture contained 25 μl KAPA Taq ReadyMix PCR Kit (Kapa Biosystems, Boston, MA, USA), 0.3 μl of each forward and reverse 50 μM primers, 19.4 μl nuclease free water, and 5 μl of genomic DNA. PCR was performed on a CFX96 System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with initial denaturation at 95 °C for 15 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 64 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products were analyzed on 2% agarose-gels, verified PCR products were purified using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), mixed with primers and submitted to 1st BASE (1st BASE, Seri Kembangan, Selangor, Malaysia) for DNA sequencing.

Statistical analysis

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to define a cut-off of ΔCT values for D29 phage assay interpretation. Accuracy, sensitivity and specificity were analyzed by using two by two table analyses. All P values were 2 tailed.

RESULTS

D29 phage assay interpretation criteria and the assay evaluation

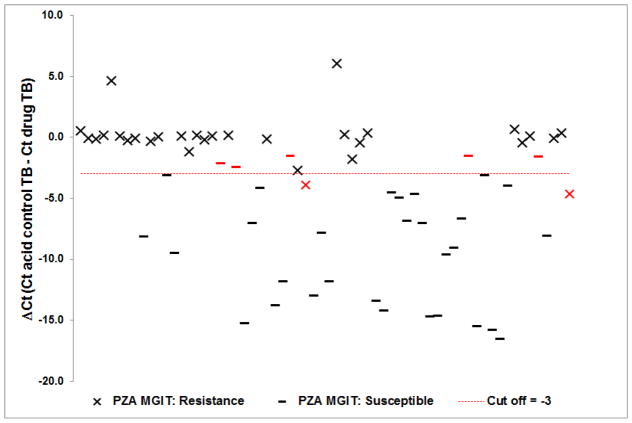

The interpretation criteria was described in our previous publication (7). Briefly, to confirm that the isolate “grew,” meaning that the isolate sufficiently allowed phage replication, we required a ΔCt of control TB (Ct of starting phage - Ct of control TB) and ΔCt of acid control TB (Ct of starting phage - Ct of acid control TB) ≥ 3.0. There were only 3 of 71 isolates that did not “grow” in control medium and 4 that did not “grow” in acid medium. To determine pyrazinamide susceptibility we used the ΔCt of (acid) control TB minus the Ct of (acid) drug TB (14) and found the optimal cut-off for resistance was ≥ −3.0 by receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) versus standard MGIT PZA results. Using this optimized cutoff the accuracy, sensitivity and specificity was 89, 94, and 85%, respectively (Table 1). We noted five isolates that were falsely resistant by phage qPCR and two that were falsely susceptible (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Performance of qPCR phage, MTT, and Sequencing compared to standard MGIT PZA susceptibility results.

| Test method | Standard MGIT (n)

|

Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rc | Sd | |||||

| Phage assaya | R | 29 | 5 | 89 | 94 | 85 |

| S | 2 | 28 | ||||

| MTT assayb | R | 29 | 8 | 83 | 88 | 78 |

| S | 4 | 28 | ||||

| Sequencing | Mt | 31e | 4 | 90 | 91 | 89 |

| Wt | 3 | 33 | ||||

7/71 did not “grow”,

2/71 did not “grow”.

18 isolates were found to have some discrepancy between the 3 methods and all were retested by MGIT whereby 6/13 originally resistant by MGIT were then deemed susceptible and 1/5 originally susceptible by MGIT was then deemed resistant. We used these as the final MGIT result.

4/31 had mixed mutant/wild-type pncA traces by sequencing and we called them mutant. Mt, mutant type. Wt, wild type.

Figure 1.

Correlation between MGIT pyrazinamide susceptibility results and D29 phage qPCR. Results of 64 M. tuberculosis isolates show the ΔCt (Ct of acid control TB - Ct of drug TB) where a value < −3.0 is defined as susceptible, and a value ≥ −3.0 is defined as resistant. Red -, x are discrepancies between D29 phage qPCR and standard MGIT results.

Evaluation of MTT assay

To define that an isolate was resistant to PZA, the color in all 3 wells (drug-containing, drug-free pH 5.9 and drug-free normal pH medium) was required to change from yellow to violet precipitate. There were only 2 of 71 isolates that did not “grow”, meaning the color did not change in drug-free (pH 5.9) or drug-free (normal pH) media. Compared with standard MGIT PZA method, accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of MTT assay was 83%, 88% and 78%, respectively (Table 1). Eight isolates were falsely resistant and four were falsely susceptible.

Correlation of pncA sequencing and standard MGIT PZA susceptibility test

The results of pncA sequencing compared to the standard MGIT PZA result is shown in Table 1. Accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of sequencing were 90%, 91% and 89%, respectively. Four were falsely resistant (pncA mutant but PZA susceptible) and 3 were falsely susceptible (pncA wild-type but PZA resistant). The specific mutations found in this repository are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mutations in pncA gene in M. tuberculosis isolates from Thailand

| No. of isolates | Nucleotide change | Codon change | Amino acid change | DST results

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGIT | MTT | Phage | ||||

| 1 | T -7 C | - | - | R | R | R |

| 2 | A -11 C | - | - | R | R | R |

| 3 | A-11G | - | - | R | R(2),S(1) | R(2),S(1) |

| 1 | T -12 C | - | - | R | R | R |

| 1 | C 28 T | CAG - TAG | Gln 10 Stop | R | R | R |

| 3 | G 34 A | GAC - AAC | Asp 12 Asn | R | R | R |

| 1 | T 40 C | TGC - CGC | Cys 14 Arg | R | R | R |

| 2 | T 92 C, T (mix) | ATC - ACC | Ile 31 Thr | S | R(1),S(1) | S |

| 1 | A 139 C | ACC - CCC | Thr 47 Pro | R | R | R |

| 1 | C 169 G | CAC - GAC | His 57 Asp | R | R | R |

| 1 | A 188 G | GAC - GGC | Asp 63 Gly | S | S | S |

| 1 | T 196 C | TCG - CCG | Ser 66 Pro | R | R | NG |

| 1 | T 202 T, A mix | TGG - AGG | Trp 68 Arg | R | R | R |

| 1 | G 314 T | GGC - GTC | Gly 105 Val | R | R | R |

| 1 | A 408 insertion | GAT – GAA, Frameshift | Asp 136 Glu | R | R | R |

| 2 | T 416 G | GTG - GGG | Val 139 Gly | R | R | R |

| 2 | C 309 C, A mix | TAC - TAA | Tyr 103 Stop | R | R | R |

| 2 | C 425 T | ACG - ATG | Thr 142 Met | R | R | R |

| 1 | A 407 G | GAT - GGT | Asp 136 Gly | R | R | R |

| 1 | C 455 C, G mix | GCC – GGC, | Ala 152 Gly | R | R | R |

| 1 | T 488 C | GTG - GCG | Val 163 Ala | S | S | S |

| 1 | T 559 G | TGA - GGA | Stop 187 Gly | R | S | R |

| 1 | C 299 C, G mix T 539 T, C mix |

ACC - AGC GTC - GCC |

Thr 100 Ser Val 180 Ala |

R | R | R |

| 1 | 365–439 deletion | Frameshift | - | R | R | R |

| 1 | 80–89 deletion | Frameshift | - | R | R | R |

| 1 | GG 391–392 insertion | GTC – GGG, Frameshift | Val 131 Gly | R | R | R |

NG; No growth

Discrepancies across methodologies

We then evaluated the methods for their consistency across the other methods. An isolate was defined as susceptible when 4 results were susceptible/0 resistant or 3 were susceptible/1 resistant. The consensus for a resistant isolate was defined identically. Ultimately, 8 isolates were impossible to adjudicate (2 susceptible results/2 resistant results). In total this resulted in 56 isolates with complete data across all methods. Since MGIT was repeated multiple times as the gold-standard it unsurprisingly had 100% accuracy versus the consensus result, whereas the phage method was 98% accurate, and MTT and sequencing were each 95% accurate (Table 3).

Table 3.

Performance of qPCR phage, MTT, and Sequencing compared to consensus majority results (n = 56).

| Test method | Consensus result (n)

|

Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | S | |||||

| Phage assay | R | 28 | 1 | 98 | 100 | 96 |

| S | 0 | 27 | ||||

| MTT assay | R | 27 | 2 | 95 | 96 | 93 |

| S | 1 | 26 | ||||

| Sequencing | Mutant | 28 | 3 | 95 | 100 | 89 |

| Wild-type | 0 | 25 | ||||

DISCUSSION

PZA susceptibility testing methods will be of increasing importance in the context of new TB drug regimens and in high MDR-TB settings. In this work we developed 2 rapid methods for PZA susceptibility testing the phage qPCR and MTT method and evaluated their performance against the MGIT PZA system as well as pncA sequencing. Accuracy and concordance across all methods was good. The MGIT PZA is the commercial standard, but it requires the MGIT 960 instrument and the kits are expensive. As has been seen before, we also found that MGIT may give false PZA resistant results, in that when we repeated 13 of the original PZA resistant results 6 of them became susceptible. This generates additional workload and cost for the lab, in that all PZA resistant results need to be repeated. Furthermore, such false resistance has generally been appreciated among otherwise pan-susceptible TB strains (4, 16, 17), but our isolates were mostly MDR, whereby this poor reproducibility of PZA resistance is even more problematic for clinicians since PZA is such an important potential drug for MDR treatment.

The colorimetric MTT assay requires no specialized instruments and the turnaround time is similar to MGIT (7 to 10 days while MGIT is 8 to 12 days). To obtain a faster result we developed the qPCR phage assay. This required 4 days to complete and can also yield a phenotypic result to any drug (7), including new drugs where molecular assays don’t exist. However it does require several steps and real-time PCR analysis. Finally we found sequencing to be 90% accurate, similar to what has generally been reported (12, 15). This method is fastest but depends on sequencing availability. It has been proposed that by knowing the exact pncA mutation that one could further improve accuracy, however our repository argued against this in that we largely found mutations associated with resistance and none of the simple variants previously associated with susceptibility (e.g., 12 of the 26 mutations we found were high confidence per Miotto et al (11)). Furthermore there were many undefined mutations. Another point to remember is that sequencing can give ambiguous results with mixtures of both mutant and wild-type sequences which can be difficult to interpret. In particular we found that 4 of 31 MGIT PZA resistant strains yielded a mixture of mutant/wild-type pncA traces. The depth of this phenomena is unclear, and we did not perform further genotyping to examine whether these were different strains or a mixture of the same strain. In sum however we conclude that any of these methods provided reasonable accuracy against the imperfect PZA MGIT method and could therefore be used depending on a laboratory’s capabilities, technologies, resources, and needed turnaround time.

Highlights.

We developed two new pyrazinamide susceptibility testing method for Tuberculosis

MTT and Phage assay provided reasonable accuracy against the PZA MGIT method

MTT assay requires no specialized instruments and turnaround time is similar to MGIT

Phage assay requires real-time PCR system but turnaround time is shorter than MGIT

MTT and Phage could be used depending on a laboratory’s capabilities and resources

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AI093358 and K24 AI102972 (to E.H.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abate G, Mshana RN, Miorner H. Evaluation of a colorimetric assay based on 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) for rapid detection of rifampicin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease: the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 1998;2:1011–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banu S, Rahman SM, Khan MS, Ferdous SS, Ahmed S, Gratz J, Stroup S, Pholwat S, Heysell SK, Houpt ER. Discordance across several methods for drug susceptibility testing of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in a single laboratory. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2014;52:156–163. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02378-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell PJ, Morlock GP, Sikes RD, Dalton TL, Metchock B, Starks AM, Hooks DP, Cowan LS, Plikaytis BB, Posey JE. Molecular detection of mutations associated with first- and second-line drug resistance compared with conventional drug susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2011;55:2032–2041. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01550-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chedore P, Bertucci L, Wolfe J, Sharma M, Jamieson F. Potential for erroneous results indicating resistance when using the Bactec MGIT 960 system for testing susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to pyrazinamide. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2010;48:300–301. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01775-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CLSI. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes - approved standard. (2) 2011;31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui Z, Wang J, Lu J, Huang X, Zheng R, Hu Z. Evaluation of methods for testing the susceptibility of clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates to pyrazinamide. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2013;51:1374–1380. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03197-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foongladda S, Klayut W, Chinli R, Pholwat S, Houpt ER. Use of mycobacteriophage quantitative PCR on MGIT broths for a rapid tuberculosis antibiogram. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2014;52:1523–1528. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03637-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foongladda S, Roengsanthia D, Arjrattanakool W, Chuchottaworn C, Chaiprasert A, Franzblau SG. Rapid and simple MTT method for rifampicin and isoniazid susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease: the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2002;6:1118–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hannan MM, Desmond EP, Morlock GP, Mazurek GH, Crawford JT. Pyrazinamide-monoresistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the United States. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2001;39:647–650. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.2.647-650.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen MB, Nielsen SE, Berg K. Re-examination and further development of a precise and rapid dye method for measuring cell growth/cell kill. Journal of immunological methods. 1989;119:203–210. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miotto P, Cabibbe AM, Feuerriegel S, Casali N, Drobniewski F, Rodionova Y, Bakonyte D, Stakenas P, Pimkina E, Augustynowicz-Kopec E, Degano M, Ambrosi A, Hoffner S, Mansjo M, Werngren J, Rusch-Gerdes S, Niemann S, Cirillo DM. Mycobacterium tuberculosis pyrazinamide resistance determinants: a multicenter study. mBio. 2014;5:e01819–01814. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01819-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morlock GP, Crawford JT, Butler WR, Brim SE, Sikes D, Mazurek GH, Woodley CL, Cooksey RC. Phenotypic characterization of pncA mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2000;44:2291–2295. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.9.2291-2295.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mshana RN, Tadesse G, Abate G, Miorner H. Use of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide for rapid detection of rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1998;36:1214–1219. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1214-1219.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pholwat S, Ehdaie B, Foongladda S, Kelly K, Houpt E. Real-time PCR using mycobacteriophage DNA for rapid phenotypic drug susceptibility results for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2012;50:754–761. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01315-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pholwat S, Stroup S, Gratz J, Trangan V, Foongladda S, Kumburu H, Juma SP, Kibiki G, Houpt E. Pyrazinamide susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by high resolution melt analysis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2014;94:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piersimoni C, Mustazzolu A, Giannoni F, Bornigia S, Gherardi G, Fattorini L. Prevention of false resistance results obtained in testing the susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to pyrazinamide with the Bactec MGIT 960 system using a reduced inoculum. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2013;51:291–294. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01838-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scarparo C, Ricordi P, Ruggiero G, Piccoli P. Evaluation of the fully automated BACTEC MGIT 960 system for testing susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to pyrazinamide, streptomycin, isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol and comparison with the radiometric BACTEC 460TB method. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2004;42:1109–1114. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1109-1114.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thom SM, Horobin RW, Seidler E, Barer MR. Factors affecting the selection and use of tetrazolium salts as cytochemical indicators of microbial viability and activity. The Journal of applied bacteriology. 1993;74:433–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb05151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]