Abstract

To examine safety and efficacy of bandage soft contact lenses (BSCLs) for ocular chronic graft-versus host disease (GVHD), we conducted a phase II clinical trial. Extended-wear BSCLs were applied under daily topical antibiotics prophylaxis. Patients completed standardized symptom questionnaires at enrollment and at 2 weeks, 4 weeks and 3 months afterwards. Ophthalmologic assessment was performed at enrollment, at 2 weeks and afterwards as medically needed. Assessments at follow-up were compared with baseline by paired t-test. Nineteen patients with ocular GVHD who remained symptomatic despite conventional treatments were studied. The mean Lee eye subscale score was 75.4 at enrollment, and improved significantly to 63.2 at 2 weeks (p=0.01), to 61.8 at 4 weeks (p=0.005) and to 56.3 at 3 months (p=0.02). The ocular surface disease index score and 11-point eye symptom ratings also improved significantly. According to the Lee eye subscale, clinically meaningful improvement was observed in 9 patients (47%) at 2 weeks, in 11 (58%) at 4 weeks and in 9 (47%) at 3 months. Visual acuity improved significantly at 2 weeks compared with enrollment values. Based on slit lamp exam at 2 weeks, punctate epithelial erosions improved in 58% of the patients, showed stability in 16% and worsened in 5%. No corneal ulceration or ocular infection occurred. BSCLs are a widely available, safe and effective treatment option that improves manifestations of ocular graft-versus host disease in approximately 50% of patients. This study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01616056.

Keywords: contact lens, dry eye disease, graft-versus-host disease, hematopoietic cell transplantation, treatment

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation is a curative treatment for many hematological malignancies and non-malignant disorders, but chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is the leading cause of late morbidity in transplant recipients, compromising both quality of life and function.1 Ocular GVHD occurs in 40 to 60% of patients with chronic GVHD.2–9 Ocular manifestations range from mild conjunctivitis and keratoconjunctivitis sicca, to severe cicatricial conjunctivitis and corneal perforation.10 Severe photophobia, eye pain, and loss of vision caused by ocular GVHD interferes significantly with patients’ activities of daily living (ADL). Superficial punctate keratitis and filamentary keratitis are the major components that cause ocular symptoms in patients with ocular GVHD. In a prospective multicenter observational cohort of patients with chronic GVHD, severity of ocular GVHD was mild in 57% of cases, moderate in 37% and severe in 6%.7

Systemic immunosuppressive therapy alone often does not completely mitigate ocular GVHD symptoms. Thus ancillary and supportive care is needed, including the frequent application of artificial tears or other ocular lubricants, the use of occlusive eyewear, or the application of topical immunosuppressive eye drops.11 The efficacy of these conventional treatments is often limited once dry eye disease is established. Lacrimal gland destruction by chronic GVHD may be irreversible even if the immunologic attack is halted. Scleral lenses are a recommended option for these severe cases.11 A case series analysis showed that the liquid corneal bandage provided by fluid-ventilated, gas-permeable scleral lenses (PROSE lenses) were effective in mitigating symptoms and resurfacing corneal erosions in the treatment of severe ocular GVHD.12 Many patients, however, are not able to access PROSE lenses because of high costs and the fact that they live far from sites that can fit PROSE lenses.

Bandage soft contact lenses (BSCLs) are widely available, disposable, soft contact lenses used for treatment of a diseased or injured cornea.13–15 Lenses are available in different diameters, with a range of different base curves, powered if necessary and in a variety of materials. Materials are chosen in order to enhance permeability to oxygen or to reduce surface deposition, and parameters are chosen in order to maximize comfort and to enhance the fitting pattern. BSCLs are much less expensive than PROSE lenses and can be fitted and dispensed on the same day. We hypothesized that protection of the surface of injured corneas with BSCLs would be safe and effective in providing relief of ocular GVHD symptoms. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a single-center, phase II trial of BSCLs for patients with ocular GVHD who are symptomatic despite conventional treatments.

Methods

Eligibility

Patients who met all of the following criteria were eligible: (1) age 18 years or older, (2) diagnosis of chronic GVHD per NIH criteria,10 (3) moderate to severe ocular GVHD10 and (4) absence of new systemic immunosuppressive medications within 1 month. Exclusion criteria were absolute neutrophil count less than 1000/µL, known hypersensitivity or allergy to contact lens care products, treatment with scleral lenses within the previous 3 months, and evidence of any active infection in the eyes. The Institutional Review Board of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center approved the study, and patients gave written consent to participate. This study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01616056.

Study procedure

Disposable extended-wear BSCLs (PureVision [Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY], lens size 14.0 to 18.0 mm, center thickness 0.05 mm) were placed for a maximum of one month at a time and were replaced every 2–4 weeks by ophthalmologists or by the patient. PureVision is a soft silicone hydrogel contact lens that has high oxygen permeability. If the patient was not comfortable with PureVision, thinner lenses (SoftLens 38 [Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY], lens size 14.0 mm, center thickness 0.038 mm) were prescribed. In addition to this principle, other BSCLs (Flexlens [Ideal Optics, Duluth, GA], lens size 14.5 to 16.0 mm, Kontur [Kontur Kontact Lens, Hercules, CA], lens size 16.0 to 22.0 mm) were considered based on corneal topography. Patients were instructed to use antibiotic eye drops (Ofloxacin, 0.3% ophthalmic solution, or Moxifloxacin HCL 0.5% ophthalmic solution) four times a day to prevent ocular infection. One lens costs 10 to 65 US dollars.

Endpoints

Patients completed the following standardized symptom questionnaires at enrollment and at 2 weeks, 4 weeks and 3 months afterwards: (1) Lee symptom scale, a 37-item validated symptom scale for chronic GVHD that contains a 3-item eye subscale (range 0–100),16 (2) Ocular surface disease index (OSDI), a 12-item validated survey that measures dry eye symptoms (range 0–100),17 and (3) 11-point eye symptom rating recommended by the NIH consensus conference where patients indicate their most bothersome eye symptom and rate it on a scale from 0–10.18 Higher scores indicate worse symptoms in these measures. All patients were surveyed at follow-up assessments even if they stopped wearing BSCLs. Patients were assessed by ophthalmologists at enrollment, at 2 weeks, and afterwards as medically needed. The ophthalmology assessments included visual acuity using the logMAR chart (ETDRS) and slit lamp exam. A logMAR value of 0 is equivalent to 20/20 vision on a Snellen chart. Corneal filaments (absence or presence) and punctate epithelial erosions (none, 1+, 2+, 3+, 4+) were assessed by slit lamp examination.9 Analysis of ophthalmology assessments was not made after 2 weeks due to incomplete data collection. The primary endpoint was symptom improvement by the Lee eye subscale after 2 weeks of therapy. Secondary endpoints included improvement in OSDI, the 11-point eye symptom rating and ophthalmologic assessments.

Statistical analysis

Measurements after placement of BSCLs were compared with baseline (enrollment) by paired t-tests. Two-sided P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Clinically meaningful changes were calculated using a threshold of 2 points on the 0–10 scale and using a half-standard deviation (SD) for other measures.18, 19 Because a previous prospective observational study7 showed that patients with NIH eye scores of 2 or 3 had SDs of 23.6 for the Lee eye subscale and 21.8 for the OSDI, clinically meaningful changes were defined as 11.8 for Lee eye subscale and 10.9 for OSDI. Improvement in ophthalmology assessments was defined as improvement in either eye without worsening in the other eye. Stability was defined as the absence of improvement or worsening in both eyes. Worsening was defined as worsening in either eye.

Sample size

Based on a previous observational study,7 the mean Lee eye subscale for eye score 2 or 3 was 67.6 and that for eye score 1 was 40.9. If we hypothesize that eye symptoms improve to eye score 1 or less in at least two thirds of patients after BSCL therapy, we would expect at least an 18-point improvement in the Lee eye subscale. Twenty patients would provide 90% power to detect a mean change of 18 points at a two-sided 0.05 level of significance.

Results

Patient characteristics

Twenty patients consented to participate in the study from August 2012 to September 2014 (Figure 1). One patient was not included in the analysis because of a protocol violation at enrollment (only one BSCL was placed while awaiting a prescription lens for the second eye). The median age was 55 years (range, 32–75). The median time from transplantation to enrollment was 36.6 months (range, 8–157 months). All patients had mobilized blood cell transplantation from an HLA-identical sibling donor (n=5; 26%), from an HLA-matched unrelated donor (n=12; 63%) or from an HLA-mismatched unrelated donor (n=2; 11%). Fourteen patients (74%) had moderate ocular GVHD and 5 (26%) had severe ocular GVHD at enrollment. All patients were taking systemic immunosuppressive treatment for chronic GVHD. The current treatment for ocular GVHD at enrollment included artificial tears (n=19; 100%), viscous ointment (n=11; 58%), cyclosporine eye drops (n=7; 37%), flax seed oil (n=6; 32%), punctal plugs (n=6; 32%), steroid eye drops (n=5; 26%), occlusive eyewear (n=5; 26%), cevimeline (n=4; 21%), autologous serum tears (n=1; 5%), and punctal cauterization (n=1; 5%). No patients had previously used scleral lenses for treatment of ocular GVHD. Other demographics of study participants are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1. CONSORT diagram.

*These 2 patients continued wearing BSCLs at 2 weeks. †Among 3 patients who did not answer questionnaires at 3 months, 2 continued wearing BSCLs and 1 stopped BSCLs due to lack of improvement.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | N=19 |

|---|---|

| Patient median age at enrollment, y (range) | 55 (32–75) |

| Median time from transplantation to enrollment, months (range) | 36.6 (8–157) |

| Patient gender, no. (%) | |

| Male | 11 (58) |

| Female | 8 (42) |

| Diagnosis at transplantation, no. (%) | |

| Acute leukemia | 7 (37) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 5 (26) |

| Malignant lymphoma | 5 (26) |

| Chronic leukemia | 2 (11) |

| Graft type, no. (%) | |

| G-CSF-mobilized blood cells | 19 (100) |

| Donor-patient gender combination, no. (%) | |

| Female to male | 4 (21) |

| Other | 15 (79) |

| HLA and donor type, no. (%) | |

| Identical sibling | 5 (26) |

| Matched unrelated | 12 (63) |

| Mismatched unrelated | 2 (11) |

| Conditioning regimen, no. (%) | |

| Myeloablative | 6 (32) |

| Non-myeloablative / reduced-intensity | 13 (68) |

| NIH eye score at enrollment, no. (%) | |

| Moderate (score 2) | 14 (74) |

| Severe (score 3) | 5 (26) |

| Systemic immunosuppressive treatment at enrollment, no. (%) | |

| Prednisone | 13 (68) |

| Sirolimus | 5 (26) |

| Tacrolimus | 4 (21) |

| Cyclosporine | 3 (16) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 2 (11) |

| Extracorporeal photopheresis | 1 (5) |

| Methotrexate | 1 (5) |

| Azathioprine | 1 (5) |

| Nirotinib | 1 (5) |

| Treatment for eye GVHD at enrollment, no. (%) | |

| Artificial tears | 19 (100) |

| Viscous ointment | 11 (58) |

| Cyclosporine eye drop | 7 (37) |

| Flax seed oil | 6 (32) |

| Punctal plugs | 6 (32) |

| Steroid eye drop | 5 (26) |

| Occlusive eyewear | 5 (26) |

| Cevimeline | 4 (21) |

| Autologous serum tears | 1 (5) |

| Punctal cauterization | 1 (5) |

G-CSF indicates granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; NIH, National Institutes of Health; and GVHD, graft-versus-host disease.

Primary endpoint

The mean Lee eye subscale score at enrollment was 75.4 ± 4.25. Compared with enrollment, the mean score improved significantly to 63.2 ± 4.82 at 2 weeks (p=0.01), to 61.8 ± 4.52 at 4 weeks (p =0.005) and to 56.3 ± 7.28 at 3 months (p=0.02) after placement of BSCLs (Figure 2A and D). Two patients changed systemic treatment before 2 weeks due to chronic GVHD activity outside the eyes (initiation of extracorporeal photopheresis for skin GVHD and azathioprine for oral GVHD, respectively), and another patient started treatment with rituximab for worsening skin sclerosis and fasciitis before the 3-month assessment. Results were similar even if these patients who changed systemic treatment were excluded from the analysis (mean score 63.2 ± 5.40 at 2 weeks; p=0.02, 62.7 ± 4.91 at 4 weeks; p=0.01, and 58.3 ± 7.76 at 3 months; p=0.06).

Figure 2. Symptom measures over time.

(A) and (D) Lee eye subscale. (B) and (E) Ocular surface disease index. (C) and (F) 11-point eye symptom ratings. Three patients did not complete survey at 3 months. Box-plots show median (thick horizontal line), 25 and 75 percentiles (box borders), and 5 and 95 percentiles (outer horizontal lines). P values were derived from paired t-test compared with baseline.

Secondary endpoints

The mean OSDI score at enrollment was 54.5 ± 6.19. Compared with enrollment, the mean score improved significantly to 36.8 ± 5.32 at 2 weeks (p=0.002), to 32.9 ± 5.74 at 4 weeks (p<0.001) and to 35.6 ± 6.50 at 3 months (p=0.001) after placement of BSCLs (Figure 2B and E). Results were similar even if patients who changed systemic treatment before assessment were excluded (mean score 37.3 ± 5.80 at 2 weeks; p=0.005, 32.2 ± 6.31 at 4 weeks; p=0.002, and 38.1 ± 7.11 at 3 months; p=0.003). The mean 11-point eye symptom rating at enrollment was 7.11 ± 0.42. Compared with enrollment, the mean score improved significantly to 5.00 ± 0.56 at 2 weeks (p=0.001), to 4.37 ± 0.45 at 4 weeks (p<0.001) and to 3.94 ± 0.59 at 3 months (p<0.001) after placement of BSCLs (Figure 2C and F). Results were similar even if patients who changed systemic treatment before assessment were excluded (mean score 4.71 ± 0.55 at 2 weeks; p<0.001, 4.35 ± 0.51 at 4 weeks; p<0.001, and 4.14 ± 0.66 at 3 months; p<0.001).

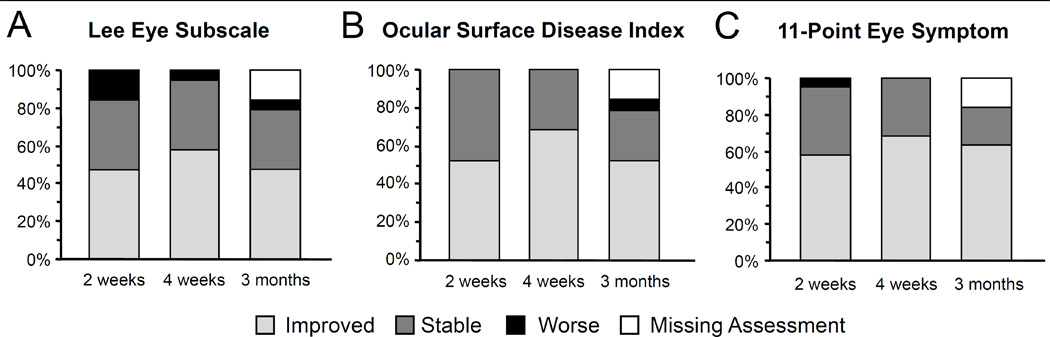

The proportions of participants who experienced clinically meaningful changes in measurements compared with enrollment are shown in Figure 3. According to the Lee eye subscale, clinically meaningful improvement (i.e. a decreased score of 11.8 or greater) was observed in 9 patients (47%) at 2 weeks, in 11 patients (58%) at 4 weeks and in 9 patients (47%) at 3 months (Figure 3A). According to OSDI scores, clinically meaningful improvement (i.e. a decreased score of 10.9 or greater) was observed in 10 patients (53%) at 2 weeks, in 13 patients (68%) at 4 weeks and in 10 patents (53%) at 3 months (Figure 3B). According to 11-point eye symptom ratings, clinically meaningful improvement (i.e. a decreased score of 2 or greater) was observed in 11 patients (58%) at 2 weeks, in 13 patients (68%) at 4 weeks and in 12 patents (63%) at 3 months (Figure 3C). Thus, 47–68% of participants experienced clinically meaningful symptom improvements with BSCL use during the 3-month study period.

Figure 3. Clinically meaningful changes in symptoms compared with baseline.

(A) Lee eye subscale. (B) Ocular surface disease index. (C) 11-point eye symptom ratings. Clinical meaningful change was defined as 2 points on the 0–10 scale and a half-standard deviation for other measures (11.8 for Lee eye subscale and 10.9 for OSDI based on a previous prospective observational study7).

Seventeen patients returned to the ophthalmology clinic and were evaluated at 2 weeks after placement of BSCLs. Two patients did not return to the clinic at 2 weeks because of personal scheduling difficulties but continued using BSCLs. The mean logMAR visual acuity at enrollment was 0.26 ± 0.030 in 38 eyes from 19 patients. Compared with enrollment, the mean logMAR visual acuity improved significantly to 0.15 ± 0.030 at 2 weeks (p=0.005; N=34 eyes; Figure 4A). Results were similar even if two patients who changed systemic treatment before assessment were excluded (mean 0.15 ± 0.032; p=0.004; N=30 eyes). Slit lamp exam at enrollment revealed corneal abnormalities in all patients, including filamentary keratitis in 20 of 38 eyes (53%) and punctate epithelial erosions in 31 of 38 eyes (82%) (grade 1: n=5, grade 2: n=17, grade 3: n=6 and grade 4: n=3 eyes). Based on follow-up slit lamp exam at 2 weeks (Figure 4B), filamentary keratitis remained absent in 8 patients (42%), resolved in 6 patients (32%) and remained present in 3 patients (16%). Punctate epithelial erosions improved in 12 patients (63%), showed stability in 4 patients (21%) and worsened in 1 patient (5%).

Figure 4. Ophthalmologic assessment at 2 weeks.

(A) Visual acuity. (B) Corneal changes assessed by slit lamp exam. P values were derived from paired t-test compared with baseline.

Compliance of study treatment

At 2 weeks, 17 patients (89%) continued wearing BSCLs. One patient stopped BSCLs due to pain, and another patient did not wear BSCLs after they fell out. At 4 weeks, 18 patients (95%) continued wearing BSCLs. One patient removed one lens due to pain. At 3 months, 2 patients (11%) stopped using BSCLs after adequate improvement in eye symptoms and 14 patients (74%) continued wearing BSCLs. One patient (5%) stopped wearing BSCLs due to blurred vision, and 2 patients (11%) stopped wearing BSCLs due to lack of improvement in eye symptoms. Among patients who continued to wear BSCLs, 17 patients (100%) at 2 weeks, 17 patients (94%) at 4 weeks and 13 patients (93%) at 3 months reported adherence to use of antibiotic drops. As of February 2015, 6 patients (32%) stopped using BSCLs after adequate improvement in eye symptoms, and 10 patients (53%) are continuing to wear BSCLs, with a median duration of 20 months (range, 6–24 months) without severe adverse events. Three patients (16%) stopped wearing BSCLs due to inadequate improvement in eye symptoms, and one of them started PROSE lenses and had moderate improvement in symptoms and ocular surface findings.

Adverse events

Adverse events after starting treatment with BSCLs are summarized in Table 2. The most frequent adverse events with BSCL therapy included foreign body sensation (n=14; 74%), swollen eyelids (n=5; 26%) and excessive tearing (n=2; 11%), but these were considered mild and rarely caused patients to discontinue BSCLs. Although it was not related to BSCL therapy, one patient had corneal edema and stromal haze suspicious of viral infection despite taking prophylaxis with systemic acyclovir. The patient was treated with trifluridine eye drops, and lesions resolved during continued BSCL wear. No corneal ulceration or ocular infection related to the use of BSCLs was documented.

Table 2.

Adverse events during the study period

| Event | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Foreign body sensation | 14 (74) |

| Swollen eye lids | 5 (26) |

| Excessive tearing | 2 (11) |

| Corneal edema and stromal haze | 1 (5) |

| Ocular infection | 0 (0) |

Discussion

Ocular involvement is one of the most frequent manifestations of chronic GVHD after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation.3, 5, 7 The pathogenesis is thought to involve dysfunction of conjunctiva and lacrimal glands caused by inflammation, resulting in tear deficiency and severe damage to the ocular surface (i.e., keratoconjunctivitis sicca).4, 6, 9, 20 Participants in our study had significant symptoms and ocular surface abnormalities despite conventional treatments including artificial tears, viscous ointment, cyclosporine eye drops, punctal plugs and steroid eye drops in addition to systemic immunosuppressive treatment. Our results showed that BSCL therapy for such patients provided prompt improvement in symptoms, visual acuity and corneal integrity in approximately 50% of patients. The results of this trial suggest that many patients who are not able to access PROSE lenses, because of cost, time and the temporary relocation required to fit PROSE lenses, may benefit from BSCLs.

We used eye symptoms as the primary endpoint in this study, as BSCLs were not expected to reverse ocular GVHD or the lacrimal damage. Prior to placement of the BSCLs, participants reported a high symptom burden from ocular GVHD. We used two standardized and validated symptom measures recommended by the NIH consensus for assessing response of ocular GVHD as well as a validated measure for dry eye disease,7, 18 and all measures showed statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in symptoms after placement of BSCLs. Furthermore, visual acuity and corneal findings as measured by slit lamp exam were improved after 2 weeks of therapy. Improvement in visual acuity was also reported in a case series of 7 patients who were treated with silicone hydrogel soft contact lenses for ocular GVHD.21

Therapeutic use of BSCLs for ocular surface diseases relieves pain, stabilizes wounds and helps corneal epithelial healing, although extended wear may cause adverse events such as corneal edema, stromal infiltrates, neovascularization, and most seriously, microbial keratitis.22, 23 Although initial studies of BSCLs for ocular surface disorders showed no episodes of microbial keratitis,21, 24 this complication has been reported particularly among patients who used lenses overnight in larger subsequent studies.25, 26 A recent study showed that the use of prophylactic antibiotic drops did not eliminate the risk of microbial keratitis in patients with chronic ocular surface disease treated with BSCLs.27 Although microbial keratitis or serious complications were not observed in GVHD patients in the current study or in a prior case series,21 larger studies are warranted to determine the risk of ocular infection in this population.

This study has some limitations. First, we did not evaluate tear film, since BSCLs were not anticipated to affect this parameter based on a previous case series showing no changes in tear breakup time after using BSCLs.21 Second, long-term safety and efficacy remain to be determined. Only two participants were able to stop BSCL therapy after 3 months after sustained adequate improvement, and 11 participants continued wearing BSCLs for more than one year, suggesting that many patients will need longer treatment. Third, we excluded children and thus cannot provide any safety and efficacy data on this population, although we believe that BSCLs should be studied in children. Lastly, this study enrolled a relatively small number of patients at a single center. A larger multi-center study is warranted to confirm these promising results.

BSCLs are a safe, tolerable and effective treatment option that improves manifestations of moderate to severe ocular GVHD in approximately 50% of patients who are symptomatic despite conventional treatments. It would be appropriate to have transplant physicians perform long-term follow-up of BSCLs once stability in symptoms and safety are confirmed, although this needs to be individualized based on patients’ reliability. Patients need to be evaluated annually by ophthalmologists as part of long-term follow-up after transplantation. Since BSCLs are widely available and do not require a high initial expense or time commitment, they could be used as the initial protective lenses for patients with ocular GVHD.

Highlights.

We conducted a phase II trial of bandage soft contact lenses (BSCLs) for ocular GVHD

Extended-wear BSCLs were applied to 19 patients under topical antibiotics prophylaxis

Eye symptoms improved dramatically after 2 weeks of BSCL therapy in 50% of patients

Visual acuity and punctate epithelial erosions also improved dramatically

BSCLs are a safe and effective treatment for moderate to severe ocular GVHD

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant U54 CA163438 from the National Institutes of Health. The Chronic GVHD Consortium (U54 CA163438) is a part of the NCATS Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN). RDCRN is an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR), NCATS, funded through a collaboration between NCATS and the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial disclosure:

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Authorship statement: Y.I., T.T.S. and S.J.L. designed the study. Y.I., X.C. and B.E.S. performed the statistical analysis. M.E.D.F., P.A.C., P.J.M. and T.T.S. provided patients. Y.I., Y.S., P.L., R.W. and S.J.L. collected data. All authors wrote and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the manuscript to be published.

References

- 1.Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2003;9:215–233. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2003.50026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franklin RM, Kenyon KR, Tutschka PJ, Saral R, Green WR, Santos GW. Ocular manifestations of graft-vs-host disease. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:4–13. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(83)34604-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tichelli A, Duell T, Weiss M, Socie G, Ljungman P, Cohen A, et al. Late-onset keratoconjunctivitis sicca syndrome after bone marrow transplantation: incidence and risk factors. European Group or Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Working Party on Late Effects. Bone marrow transplantation. 1996;17:1105–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogawa Y, Okamoto S, Wakui M, Watanabe R, Yamada M, Yoshino M, et al. Dry eye after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1999;83:1125–1130. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.10.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flowers ME, Parker PM, Johnston LJ, Matos AV, Storer B, Bensinger WI, et al. Comparison of chronic graft-versus-host disease after transplantation of peripheral blood stem cells versus bone marrow in allogeneic recipients: long-term follow-up of a randomized trial. Blood. 2002;100:415–419. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SK. Update on ocular graft versus host disease. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2006;17:344–348. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000233952.09595.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inamoto Y, Chai X, Kurland BF, Cutler C, Flowers ME, Palmer JM, et al. Validation of measurement scales in ocular graft-versus-host disease. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietrich-Ntoukas T, Cursiefen C, Westekemper H, Eberwein P, Reinhard T, Bertz H, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of ocular chronic graft-versus-host disease: report from the German-Austrian-Swiss Consensus Conference on Clinical Practice in chronic GVHD. Cornea. 2012;31:299–310. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318226bf97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogawa Y, Kim SK, Dana R, Clayton J, Jain S, Rosenblatt MI, et al. International Chronic Ocular Graft-vs-Host-Disease (GVHD) Consensus Group: proposed diagnostic criteria for chronic GVHD (Part I) Scientific reports. 2013;3:3419. doi: 10.1038/srep03419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, Socie G, Wingard JR, Lee SJ, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2005;11:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couriel D, Carpenter PA, Cutler C, Bolanos-Meade J, Treister NS, Gea-Banacloche J, et al. Ancillary therapy and supportive care of chronic graft-versus-host disease: national institutes of health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic Graft-versus-host disease: V. Ancillary Therapy and Supportive Care Working Group Report. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12:375–396. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahide K, Parker PM, Wu M, Hwang WY, Carpenter PA, Moravec C, et al. Use of fluid-ventilated, gas-permeable scleral lens for management of severe keratoconjunctivitis sicca secondary to chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2007;13:1016–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donnenfeld ED, Selkin BA, Perry HD, Moadel K, Selkin GT, Cohen AJ, et al. Controlled evaluation of a bandage contact lens and a topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug in treating traumatic corneal abrasions. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:979–984. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30926-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oskouee SJ, Amuzadeh J, Rajabi MT. Bandage contact lens and topical indomethacin for treating persistent corneal epithelial defects after vitreoretinal surgery. Cornea. 2007;26:1178–1181. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318151f811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blackmore SJ. The use of contact lenses in the treatment of persistent epithelial defects. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2010;33:239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee S, Cook EF, Soiffer R, Antin JH. Development and validation of a scale to measure symptoms of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2002;8:444–452. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12234170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, Hirsch JD, Reis BL. Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:615–621. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pavletic SZ, Martin P, Lee SJ, Mitchell S, Jacobsohn D, Cowen EW, et al. Measuring therapeutic response in chronic graft-versus-host disease: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: IV. Response Criteria Working Group report. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12:252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1998;16:139–144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, McDonald GB, Striker GE, Sale GE, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man. A long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. The American journal of medicine. 1980;69:204–217. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russo PA, Bouchard CS, Galasso JM. Extended-wear silicone hydrogel soft contact lenses in the management of moderate to severe dry eye signs and symptoms secondary to graft-versus-host disease. Eye & contact lens. 2007;33:144–147. doi: 10.1097/01.icl.0000244154.76214.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poggio EC, Glynn RJ, Schein OD, Seddon JM, Shannon MJ, Scardino VA, et al. The incidence of ulcerative keratitis among users of daily-wear and extended-wear soft contact lenses. The New England journal of medicine. 1989;321:779–783. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198909213211202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sankaridurg PR, Sweeney DF, Sharma S, Gora R, Naduvilath T, Ramachandran L, et al. Adverse events with extended wear of disposable hydrogels: results for the first 13 months of lens wear. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1671–1680. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanpolat A, Ucakhan OO. Therapeutic use of Focus Night & Day contact lenses. Cornea. 2003;22:726–734. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200311000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schein OD, McNally JJ, Katz J, Chalmers RL, Tielsch JM, Alfonso E, et al. The incidence of microbial keratitis among wearers of a 30-day silicone hydrogel extended-wear contact lens. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:2172–2179. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stapleton F, Edwards K, Keay L, Naduvilath T, Dart JK, Brian G, et al. Risk factors for moderate and severe microbial keratitis in daily wear contact lens users. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1516–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saini A, Rapuano CJ, Laibson PR, Cohen EJ, Hammersmith KM. Episodes of microbial keratitis with therapeutic silicone hydrogel bandage soft contact lenses. Eye & contact lens. 2013;39:324–328. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e31829fadde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]