Abstract

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex behavioral condition with onset during early childhood and a lifelong course in the vast majority of cases. To date, no behavioral, genetic, brain imaging, or electrophysiological test can specifically validate a clinical diagnosis of ASD. However, these medical procedures are often implemented in order to screen for syndromic forms of the disorder (i.e., autism comorbid with known medical conditions). In the last 25 years a good deal of information has been accumulated on the main components of the “endocannabinoid (eCB) system”, a rather complex ensemble of lipid signals (“endocannabinoids”), their target receptors, purported transporters, and metabolic enzymes. It has been clearly documented that eCB signaling plays a key role in many human health and disease conditions of the central nervous system, thus opening the avenue to the therapeutic exploitation of eCB-oriented drugs for the treatment of psychiatric, neurodegenerative, and neuroinflammatory disorders. Here we present a modern view of the eCB system, and alterations of its main components in human patients and animal models relevant to ASD. This review will thus provide a critical perspective necessary to explore the potential exploitation of distinct elements of eCB system as targets of innovative therapeutics against ASD.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13311-015-0371-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Words: Autism spectrum disorder, endocannabinoid system, fragile X syndrome, metabolic regulation, reward system

The Endocannabinoid System

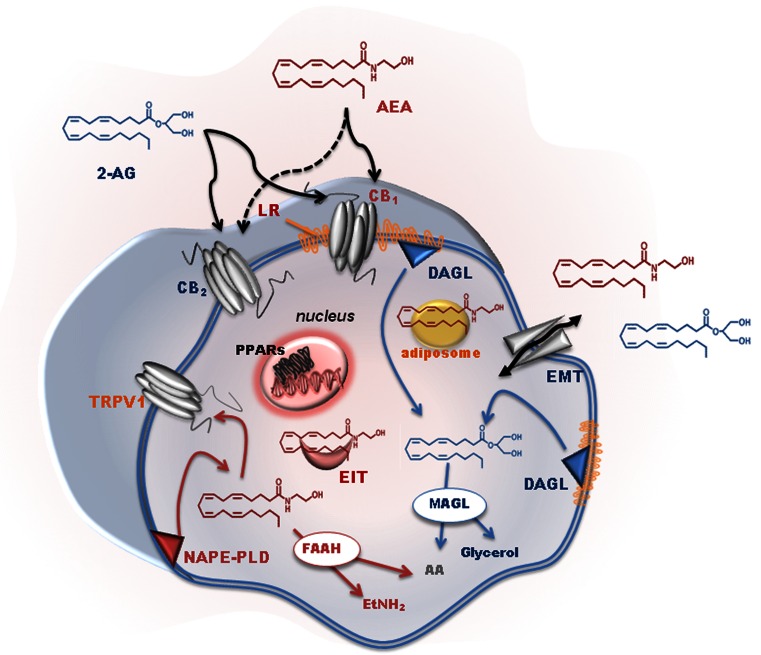

Twenty-five years after the cloning and expression of a complementary DNA that encoded a G protein-coupled receptor, named type-1 cannabinoid (CB1) receptor [1], there is a good deal of information on the main components of the so-called “endocannabinoid (eCB) system”, as well as on its role in controlling cannabinergic signaling in human health and disease [2–4]. Anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) are the most active eCBs as yet identified, although this family of bioactive lipids includes other arachidonic acid (AA) derivatives with cannabimimetic properties (i.e., noladin ether, virodhamine, N-arachidonoyldopamine, to name but a few). The classical dogma that eCBs are synthesized and released “on demand” upon (patho)physiological stimuli has been recently revisited on the basis of unexpected evidence for intracellular reservoirs and transporters of eCBs. These new entities have been shown to drive intracellular trafficking of eCBs, adding a new dimension to the regulation of their biological activity [5]. To date, several metabolic routes have been described for AEA biosynthesis [6, 7], yet the most relevant pathway is believed to begin with the transfer of AA from the sn-1 position of 1,2-sn-di-arachidonoyl-phosphatidylcholine to phosphatidylethanolamine, generating the AEA precursor N-arachidonoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine. The latter compound is next cleaved by a specific N-acyl-phosphatidylethanolamine (NAPE)-specific phospholipase D, which has been characterized in detail [8]. However, the degradation of AEA to AA and ethanolamine is mainly due to 2 fatty acid amide hydrolases (FAAH and FAAH-2) [9, 10]. When FAAH and FAAH-2 are inhibited, N-acylethanolamine-hydrolyzing acid amidase cleaves AEA in an alternate route [11, 12]. The main enzymes responsible for AEA metabolism are reported in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the main elements of the endocannabinoid (eCB) system. N-arachidonoylethanolamine (AEA) is mainly synthesized by the sequential activity of N-acyltransferase (not shown) and N-acylphosphatidyl-ethanolamine (NAPE)-specific phospholipase D (NAPE-PLD). The intracellular degradation of AEA is due to a fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) that generates ethanolamine (EtNH2) and arachidonic acid (AA). 2-Arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) is released from membrane lipids through the activity of diacylglycerol lipase (DAGL), and can be hydrolyzed by a cytosolic monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL), which releases glycerol and AA. Cyclooxygenase-2, lipoxygenase isozymes and cytochrome P450 were omitted for the sake of clarity. Extracellular eCBs can cross the plasma membrane through a purported eCB membrane transporter (EMT), and then they are trafficked within the cytoplasm through eCB intracellular transporters (EIT), which deliver them to their different targets or, alternatively, to storage organelles like adiposomes. Both AEA and 2-AG trigger several signal transduction pathways by acting at type-1 and type-2 cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2, respectively), or at other non-CB1/non-CB2 targets, such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) in the nucleus. CB1, but not CB2, resides within specialized membrane microdomains enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids, which are called lipid rafts (LR). AEA (and also 2-AG) can also translocate to the inner membrane leaflet, where it binds to transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) channels

Much like AEA, the biological activity of 2-AG is controlled through cellular mechanisms that include: 1) synthesis through rapid hydrolysis of inositol phospholipids by a specific phospholipase C to generate diacylglycerol that is then converted into 2-AG by a sn-1-specific diacylglycerol lipase (DAGL) [13]; and 2) degradation to AA and glycerol by a monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) [14], as schematically represented in Fig. 1. AEA and 2-AG can be also oxidized by cyclooxygenase-2, different lipoxygenase isozymes, as well as by cytochrome P450, to generate, respectively, prostaglandin–ethanolamides [15] and prostaglandin-glyceryl esters [16], hydroxy-anandamides and hydroxyleicosatetraenoyl-glycerols [17], and epoxy-eicosatrienoyl-glycerols [18].

An open question concerning eCB metabolism remains the transport of these compounds across the plasma membrane [19, 20]. As yet, the most accepted mechanisms are: 1) passive diffusion, which can be favored by the formation of AEA–cholesterol complexes, possibly in preferred microdomains called “lipid rafts” [21, 22]; 2) facilitated transport through a purported eCB membrane transporter [23]; and 3) endocytosis assisted by caveolins (reviewed in [24]). Once taken up, intracellular AEA reaches distinct sites, where distinct metabolic and signaling pathways take place. Heat shock protein 70, and albumin and fatty acid binding proteins 5 and 7 have been shown to act as eCB intracellular transporters, able to ferry AEA (and likely also 2-AG) within the cytoplasm to the nucleus and other destinations, including storage compartments like adiposomes [5, 25].

eCBs act principally through type-1 and type-2 (CB1 and CB2) cannabinoid receptors. Interestingly, CB1 but not CB2 resides within lipid rafts, and their interaction with these specialized microdomains influences signal transduction thereof [26]. Additionally, eCBs are also able to interact with non-CB1/non-CB2 targets, such as 1) the transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 channel, which is activated by both AEA and 2-AG [27, 28]; 2) peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ [29]; and 3) the orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR55 [30, 31]. By interacting with these receptors, eCBs trigger a multiplicity of signaling pathways that are involved in both physiological and pathological conditions [32]. On a final note, the existence of compounds structurally related to eCBs, and collectively known as “eCB-like” substances, should be recalled because of their “entourage effect”. These compounds potentiate eCB activity at their receptors by increasing binding affinity or by inhibiting eCB hydrolysis [33–35]. A schematic representation of eCBs, their molecular targets, biosynthetic and hydrolizing enzymes, and extra- and intracellular transporters, is depicted in Fig. 1.

Autism Spectrum Disorder: Clinical Traits, Neuropsychological Deficits, and Neuroanatomical Underpinnings

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex behavioral condition with onset during early childhood and a lifelong course in the vast majority of cases. It is characterized by deficits in communication and social interaction, as well as by stereotypic behaviors, restricted patterns of interest, and abnormal sensory issues [36]. The diagnosis is based on clinical observation, substantiated by standardized testing of the patient with the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic [37], later revised into the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-2 [38], and/or by parental interview with the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised [39]. To date, no behavioral, genetic, brain imaging, or electrophysiological test can specifically validate a clinical diagnosis of ASD, although these medical procedures are regularly implemented in order to screen for syndromic forms of the disorder (i.e., autism due to known medical conditions). Two essential features distinguish ASD from most other behavioral disorders: 1) an impressive clinical and pathogenetic heterogeneity, which has led to the designaton, by the term “autisms”, of a set of neurodevelopmental disorders with early onset in life, sharing autism as a common feature, but produced through distinct processes [40]; 2) the distribution of autistic features as a dimensional continuum in the general population, which fully justifies referring to the “autism spectrum” rather than to a categorical distinction between “affected” and “unaffected” [41, 42]. As many as 1 in 68 (1.6 %) 8-year-old children receive an ASD diagnosis [43], with a male:female ratio of 4:1. Siblings of children already diagnosed with ASD have a significantly higher incidence of the same disorder, reported at 18.7 % in a prospective follow-up study [44], and ranging from 15 % to 25 % depending on sex and clinical severity. The prospective follow-up of these siblings later diagnosed with ASD has led to the observation that some behavioral abnormalities can appear very early on (e.g.,, sensory issues [e.g., extreme responses to certain sounds/textures, fascination with lights/spinning objects] are already present at 7 months of age), others emerge at 12–14 months (e.g., disengagement of visual attention), while the bulk of more typical autistic abnormalities has an onset between 14 and 24 months [45–48]. Frequently, comorbid conditions include intellectual disability (65 %), seizures (30 %), and different forms of sleep problems [49–51]; less recognized, but equally impairing, are frequent psychiatric comorbidities, that include anxiety disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorders, and depression [52]. Altered neurodevelopment during early pregnancy represents the neuropathological cause of ASD [53, 54]. Postmortem studies have unveiled neuroanatomical and cytoarchitectonic abnormalities in the cerebellum, inferior olivary complex, deep cerebellar nuclei, hippocampus, amygdala, entorhinal cortex, fusiform gyrus, and anterior and posterior cingulate cortex, with thinner cortical minicolumns, excessive growth of the frontal lobes, and excessive dendritic spine density [55]. These abnormalities are suggestive of derangements occurring during the first/second trimester of pregnancy, namely reduced programmed cell death and/or increased cell proliferation, altered cell migration, abnormal cell differentiation with reduced neuronal body size, abnormal neurite sprouting, and pruning that result in atypical cell–cell wiring. In addition, neurodevelopmental mechanisms extending into late prenatal/postnatal life include reduced synapse formation and delayed myelination [40, 56, 57]. The latter result in abnormal neuronal wiring, which was previously believed to be characterized by long-range hypoconnectivity and local hyperconnectivity [58], but more recently has been shown to be a highly individualized mix of hyper- and hypoconnectivity specific to each single patient with ASD [59]. These abnormalities have been associated with deficits in multiple behavioral tasks that relate to social behavior, such as empathy, theory of mind, joint attention, and face and emotion processing. Many of these observed behavioral features suggest a deficit in the social reward processing system in ASD, as we discuss in the following section. The neurocognitive phenotype in ASD stems from a complex and highly heterogeneous array of genetic and environmental causes, with patients ranging from “purely genetic” cases due to known ASD-causing chromosomal aberrations or mutations to “purely environmental” cases due to rare prenatal exposure to specific viral agents, drugs, and toxins [60–62]. In between these extremes, ASD for most cases fully qualifies for the definition of a “complex” disorder, whereby a host of rare and common genetic variants, often but not necessarily in conjunction with epigenetic factors [63], yield the neurodevelopmental abnormalities summarized above, resulting in autistic behaviors. Finally, neuroinflammation is also a frequent finding in postmortem brains of autistic individuals [64, 65]. It may represent a nonspecific consequence of insufficient neurite pruning and abnormal wiring of neural networks, resulting in elevated oxidative stress (possibly a common feature shared by several neurodevelopmental disorders) [66], but it could also stem from a broader immune dysfunction which, together with gastrointestinal disturbances and recurrent infections, collectively qualifies ASD as a systemic disorder [67–71].

Autism and Reward System

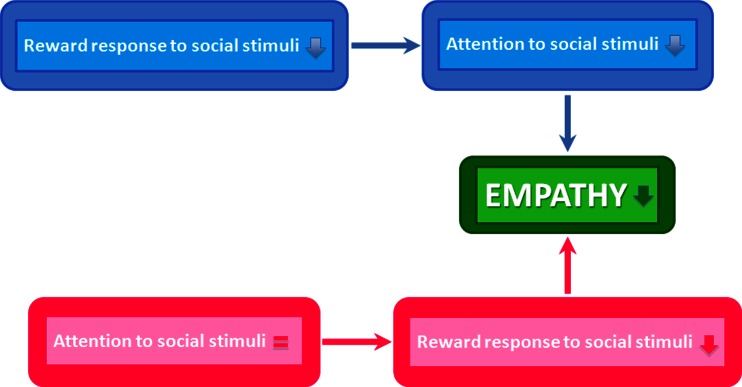

A deficit in theory of mind and empathy has commonly been suggested to underlie atypical social behavior in individuals with ASD [72]. A set of recent studies raises the possibility that some of these social behavioral deficits in ASD arise due to deficits in reward system functioning [73–75]. This hypothesis is supported by studies that report a lack of social motivation in children with autism [76, 77]. One rationale for the social motivation-based account of ASD relies on the following premise: if individuals with ASD do not find social stimuli rewarding, and hence do not attend to them as much as neurotypicals, then they are less likely to exhibit empathy toward them. An alternative formulation of the social motivation hypothesis suggests that the attention of individuals with and without ASD is drawn to social stimuli to a comparable extent, but individuals with ASD find social stimuli less rewarding, which leads to the observed deficits in empathy (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Two possible routes through which atypical reward processing can lead to reduced empathy as seen in ASD. (Top panel) The first of these routes suggest that a lower reward response to social stimuli reduces the salience of social stimuli and hence how much attention they capture. The reduced empathy is therefore a product of this reduced attention to social stimuli. (Bottom panel) A second possible route suggests comparable salience for social and nonsocial stimuli in ASD, but lower value for social stimuli in ASD, leading to reduced empathy

Both of these possible accounts of the social motivation hypothesis are faced with a key question. Do people with ASD find social stimuli rewarding or do they have a domain-general dysfunction of the reward system? To test these possibilities, a number of studies have compared processing of social and nonsocial reward stimuli in people with and without ASD. An early study using a continuous performance task found no behavioral evidence for group differences in trials with monetary rewards versus nonrewards [78]. Similarly, comparable behavioral performance in a reward-processing task using a variant of the go–no-go task was found in children and adults with and without ASD [79, 80]. In contrast, using a similar task, DeMurie et al. [81] demonstrated that children with ASD were slower in responding to social rewards than monetary rewards, but this was not specific to ASD. Overall, the behavioral evidence summarized above appears equivocal about any circumscribed deficit in social reward processing in ASD. Yet, a main group effect in the majority of these studies points toward a domain-general deficit in the reward system. In contrast to the behavioral studies using button-press responses, eyegaze tracking, electroencephalography, and functional magnetic resonance imaging studies suggest clear differences in processing of social rewards in ASD compared with typically developed controls [82]. Eyegaze tracking studies typically involve measuring gaze fixation patterns in response to social and nonsocial stimuli. Children and adults with ASD are found to look less at social stimuli than at nonsocial stimuli [83–85]. Gaze fixation patterns have often been used as proxy metrics related to reward processing [86], thus supporting the hypothesis of atypical processing of social rewards in ASD. Using electroencephalography in children with ASD, a recent study reported lower magnitude of a component related to reward anticipation (stimulus preceding negativity) in response to social versus nonsocial stimuli [87]. Similarly, functional magnetic resonance imaging studies revealed lower activity in the ventral striatum in response to social stimuli (neutral faces) in individuals with ASD [88]. The latter finding is consistent with the observation that a reduced ventral striatal response to happy faces was associated with lower self-reported empathy in individuals with and without ASD [89].

In sum, there is substantial evidence across different techniques to suggest atypical reward processing in ASD. Irrespective of their domain specificity, such functional differences in the reward circuit in ASD have important consequences for the processing of social stimuli. Atypical response to social rewards from an early age can result in deficits in learning about the social world, which, in turn, can lead to social behavioral impairments in adulthood.

Alterations of the eCB System in Autism

The complexities that make autism hard to understand, from the diagnostic criteria and clinical heterogeneity to the genetic/environmental causes that provoke communication and behavioral problems to the innovative therapies to be applied in order to give patients the best quality of life, encourage scientists to look at predictive biomarkers and/or therapeutic targets for the pharmacological management of this disorder [90, 91]. It is now clear that eCB system is altered in several neurodegenerative diseases and, very interestingly, that distinct elements of the eCB system in peripheral blood mirror these perturbations, providing novel and noninvasive diagnostic tools for several neuroinflammatory diseases [92, 93]. In addition, the eCB system controls emotional responses [94], behavioral reactivity to context [95], and social interaction [96]. Thus, it can be hypothesized that alterations in this endogenous circuitry may contribute to the autistic phenotype. In this and the following sections, we critically discuss the evidence for this proposition from animal and human studies. Recent investigations have addressed the involvement of eCBs in autism, where, unfortunately, the role of these bioactive lipids remains poorly understood. Indeed, autism is uniquely human and there are only a few validated animal models (e.g., fmr1 knockout mice, BTBR mice, and valproic acid-treated rats), that display autistic-like features. Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is an inherited disorder caused by mutations in FMR1, which is translated into the fragile X mental retardation 1 protein, which, in turn, plays a role in the development of synapses [97, 98]. Expansion mutations of FMR1 produce autistic features in approximately 40 % of patients with FXS, and thus FXS provides a valuable model for identifying novel biomarkers/targets for autism and for dissecting the underlying neurochemical pathways [99]. In the first study addressing eCB system in FXS, it has been reported that the ablation fmr1 gene causes a dysfunctional 2-AG metabolism, with increasing DAGL and MAGL activities in the striatum of fmr1–/– mutants, but unaltered striatal 2-AG levels [100]. According to a more recent study [101], stimulation of 2-AG signaling could be a useful treatment for mitigating FXS symptoms because it is able to normalize synaptic activity through type I metabotropic glutamate activation; additionally, genetic or pharmacological attenuation of CB1-dependent signal transduction and blockade of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway might provide alternative strategies to treat autistic patients [102].

A link between the eCB system and autism was put forward by Schultz [103], who proposed that acetaminophen, an antipyretic drug that is metabolized to a potent inhibitor of the purported eCB membrane transporter AM404, could trigger autism by activating CB receptors. In line with this, elevated levels of circulating AEA during pregnancy or in the first postnatal days might interefere with the neurodevelopment of offspring, and might increase the risk of delivering autistic children. Abnormalities in sociability and nociception tests, and alterations of distinct elements of eCB system have been reported in adolescent rats on valproic acid [104]. In particular, mRNA levels of the enzymes responsible for 2-AG metabolism (i.e., DAGL and MAGL), which is disrupted in the FXS model of autism [100], were altered in the cerebellum and hippocampus, whereas endogenous levels of 2-AG in the same regions remained at steady state [104]. Interestingly, the content of AEA, N-oleoylethanolamine (OEA), and N-palmitoylethanolamine (PEA), all of which are substrates of FAAH, were increased in the hippocampus following exposure to sociability tests, suggesting that a deficit in social play behaviors might be due to reduced AEA levels in critical brain areas [104]. Moreover, the same study documented a downregulation of GPR55 and PPAR gene expression, supporting a role for these receptors in the cognitive mechanisms involved in autism [104]. Preliminary data also addressed CB2 as a potential target for autism. Indeed, genomic studies have highlighted an upregulation of mRNA levels of the CB2A, but not the CB2B, isoform in the cerebellum of BTBR T + tF/J mice [105], which have an autism-like behavioral phenotype [106]. Also, an independent clinical study performed on young (3–9-year-old) children demonstrated that CB2 is highly expressed, both at transcriptional and translational levels, in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with autism, compared with matched healthy controls [107]. All the other elements of the eCB system remained unaltered, except for a slight downregulation of NAPE–phospholipase D mRNA. According to a recent hypothesis on autism and inflammation [108], and in keeping with data on the key role of CB2 in immune-related pathologies [109–111], it can be speculated that the increase in CB2 expression may serve a compensatory role with respect to the inflammatory state associated with autism. Thus, the observed enhancement of CB2 may be a negative feedback response aimed at counteracting the proinflammatory responses implicated in the pathogenesis of this neurobehavioral condition. In this context, it should be also recalled that AEA suppresses the release of proinflammatory cytokines from human lymphocytes through a CB2-mediated mechanism [112]. The main alterations of the eCB system in human patients and animal models of autism are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. However, the paucity of the relevant human data and their largely correlational nature do not allow for a systematic comparison with the animal data.

Table 1.

Molecular markers of the endocannabinod (eCB) system in autism and related phenotypes in humans

| Biological sample | Model | eCB alterations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postmortem brain | Human | ↓CB1 | [121] |

| PBMCs | Human | ↓NAPE–PLD mRNA = FAAH, CB1 mRNA ↑CB2 mRNA and protein |

[107] |

| Saliva | Human | CB1 SNP | [116, 119] |

PBMCs = peripheral blood mononuclear cells; CB1 = type-1 cannabinoid receptor; NAPE–PLD = N-acylphosphatidyl-ethanolamine-specific phospholipase D; FAAH = fatty acid hydrolase; CB2 = type-2 cannabinoid receptor; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism

Table 2.

Molecular markers of the eCB system in autism-related animal models

| Biological sample | Model | eCBs alterations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Striatum | fmr1 –/– mouse | =2-AG levels ↑DAGL and MAGL activity |

[100] |

| Cerebellum | Rat valproic acid | = AEA, OEA, PEA and 2-AG levels ↓DAGLα mRNA |

[104] |

| Frontal cortex | = AEA, OEA, PEA and 2-AG levels ↓PPAR-α and ↓GPR55 mRNA |

||

| Hippocampus | ↑AEA, ↑OEA, ↑PEA content* ↓PPAR-γ and ↓GPR55 mRNA ↓MAGL mRNA ↑MAGL activity |

||

| Cerebellum | BTBR T + tF/J mouse | ↑CB2A isoform mRNA | [105] |

2-AG = 2-arachidonoylglycerol; DAGL = diacylglycerol; MAGL = monacylglycerol lipase; AEA = anandamide; OEA = N-oleoylethanolamine; PEA = N-palmitoylethanolamine; PPAR = peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

*After sociability tests

Additionally, it is worth noting that plasma levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids (which are components of eCBs) are lower in patients with autism, and that 2 derivatives of docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid (also components of eCBs) are able to activate both CB1 and CB2 receptors [113]. These data further suggest that a dysregulation of eCB signaling might be driven by diet, resulting in an imbalance of pro- and anti-inflammatory metabolites, and thus favoring the development of autism [114].

Suggested Roles of the eCB System in Autism

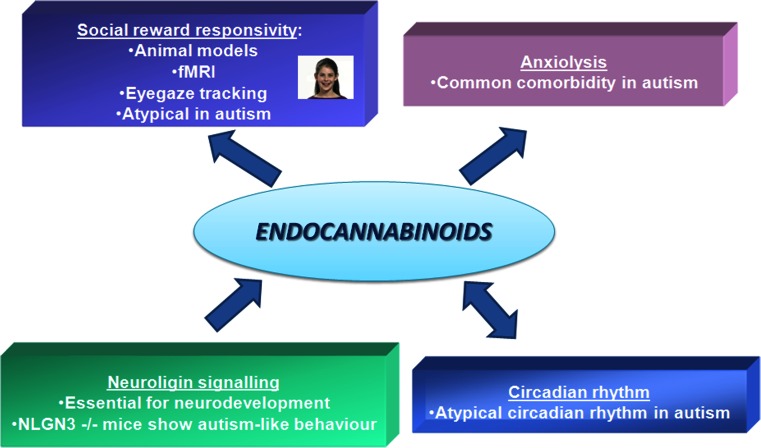

As discussed in the previous sections, there is phenotypic evidence across multiple levels that suggests a role for atypical reward system functioning in ASD. It is therefore vital to investigate in detail the eCB system in autism and related endophenotypes, also in view of its key role in modulating mesolimbic dopaminergic neurotransmission. The majority of studies on the eCB system in autism-related endophenotypes in humans have tested the role of the CNR1, which is strongly expressed in striatal structures implicated in processing rewards [115]. The previous section presented an overview of largely animal studies that point to a role for eCB signaling in autism-relevant phenotypes. Further clues from both human and animal studies are discussed in the following section, and are summarized in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Four clues pointing to the role of the endocannabinoid (eCB) system in autism. The eCB system constitutes a relatively less investigated piece of a puzzle that brings together 4 phenotypic features known to be atypical in autism: 1) social reward responsivity; 2) neural development; 3) circadian rhythm; and 4) anxiety-related symptoms. fMRI = functional magnetic resonance imaging

The first clue comes from a human neuroimaging study that measured striatal response to social rewards (happy faces vs neutral faces). This investigation found that common single nucleotide polymorphisms in CNR1 are associated with activity in the ventral striatal cluster in response to happy (but not to disgusted) faces [116], and later on it was replicated in an independent cohort [117]. In view of the central role of the ventral striatum in reward processing, it is reasonable to infer that variation in CNR1 was linked to differences in sensitivity to social rewards such as happy faces. Another study in an independent sample used eyegaze tracking to show that the same CNR1 polymorphisms were associated with greater gaze duration to happy faces, but again not to disgust faces [118]. A parallel population genetic study found a nominal association of the same CNR1 genetic variations with trait empathy [119]. Individuals with ASD score low in trait empathy, and, consistent with this, a gene expression study in postmortem brains of individuals with autism had earlier reported a reduced expression of CB1 [120, 121]. In sum, multiple indirect lines of evidence suggest a role for CNR1 genetic variations in underlying social reward responsivity, a putative endophenotype for autism. These findings in human patients parallel observations in animal models that show a strong role for the eCB system in social play behavior, which is a proxy measure for social reward responsivity [122, 123].

A second clue for the role of eCB system in autism comes from observations in early neural development [124]. Autism is neurodevelopmental in nature, and atypical development of neural connectivity has been suggested to underlie its key phenotypic features [125]. A set of genes involved in neurodevelopmental processes that mediate the formation, stabilization, and pruning of synapses has been consistently associated with autism-related phenotypes in animal models [126–128]. Neuroligins (NLGN) represent a significant part of this set, and indeed several genes of NLGN family have been associated with autism [129]. In a mouse model, an autism-associated mutation in NLGN3 was found to be associated with deficits in social behavior and disrupted tonic eCB signaling [130, 131]. Evidence from this study and several others (reviewed in [124]) provides a potential causal bridge between atypical neural development and potential dysfunction of the eCB system in autism.

A third clue comes from the role of the eCB system in influencing circadian rhythm in animal models [132–134]. Autism has been associated with atypical sleep patterns and circadian rhythms [135]. Polymorphisms in ASMT (involved in melatonin synthesis), paralleled by reduced levels of circulating melatonin, have been reported in autism [136]. Interestingly, the eCB system also plays a role in regulating circadian rhythms [134], thus making it a putative target to examine using animal models of autism-related phenotypes.

The fourth clue comes from comorbidities commonly observed in autism. First of these is anxiety, which is highly comorbid with autism (42–56 %). The eCB system, and cannabidiol in particular, is known to mediate anxiety and related phenotypes [137, 138]. Anecdotal reports of cannabis use in autism suggest a reduction in anxiety-related symptoms. A potential role for the eCB system in ASD can thus also be mediated through its influence on the anxiety-related component of the disease. The second commonly occuring comorbidity in autism relevant to the current review is epilepsy (up to 30 %). The eCB system is studied intensively as targets for potential antiepileptic drugs [139]. It is therefore possible that a potential future drug acting on the eCB system is better able to ameliorate epilepsy-related comorbidities in ASD.

Conclusions

Accumulated evidence suggests that the eCB system constitutes a relatively less investigated piece of a puzzle that brings together 4 phenotypic features known to be atypical in autism: 1) social reward responsivity; 2) neural development; 3) circadian rhythm; and 4) anxiety-related symptoms. Therefore, the potential therapeutic exploitation of distinct elements of this system (e.g., receptor targets, biosynthetic and hydrolytic enzymes, and transmembrane/intracellular transporters) seems immense. As supported by the evidence presented in the previous sections in humans and animal models, any potential therapeutic approach is unlikely to involve a simple choice between activation versus inhibition of the eCB system to target specific features related to autism. Any such approach will need to be precisely tuned to the developmental timeline and to the specific pathogenetic underpinnings of autism in the single patient. Our understanding of eCB signaling in autism is still in its infancy compared with other disorders of the central nervous system or of peripheral tissues, where eCB-based therapies have already reached preclinical and clinical phases [4]. However, research in this field is rapidly evolving, and novel drugs able to hit specifically a distinct element of the eCB system are developed at a surprising speed [4]. Among them, those that target metabolic enzymes of eCBs, and, at the same time, key enzymes of oxidative pathways like cyclooxygenases seem to hold promise as next-generation therapeutics against human disorders with an inflammatory component [140], and therefore they will possibly result in also being beneficial for ASD. A second medium-term target could focus on the antiepileptic drugs that are being developed, focusing on the eCB system. These drugs could potentially ameliorate the epilepsy-related symptoms that commonly co-occur with ASD. On a final note, it seems of major interest that preliminary data, showing consistency between changes in distinct eCB system elements (i.e., CB2) in animal models of ASD and in peripherabl blood mononuclear cells from young patients with ASD [106, 107], support a role for these elements in the (early) diagnosis of the disease. Future work should test expression profiles for key players of the eCB system in prospective samples to test the potential of these as diagnostic biomarkers. In this context, it should be recalled that easily accessible biomarkers of neurological disorders are highly searched for, and some of them have been already identified to hold promise in human neurodegenerative/neuroinflammatory diseases [141].

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 506 kb)

Acknowledgments

This investigation was partly supported by Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca (PRIN 2010-2011 grant) to MM. BC was supported by Medical Research Council UK (grant: G1100359/1).

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Footnotes

B. Chakrabarti, A. Persico and N. Battista are equal first authors.

References

- 1.Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pacher P, Kunos G. Modulating the endocannabinoid system in human health and disease-successes and failures. FEBS J. 2013;280:1918–1943. doi: 10.1111/febs.12260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maccarrone M, Guzman M, Mackie K, Doherty P, Harkany T. Programming and reprogramming neural cells by (endo-)cannabinoids: from physiological rules to emerging therapies. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:786–801. doi: 10.1038/nrn3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maccarrone M, Bab I, Bíró T, et al. Endocannabinoid signaling at the periphery: 50 years after THC. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36:277–296. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maccarrone M, Dainese E, Oddi S. Intracellular trafficking of anandamide: new concepts for signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:601–608. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ueda N, Tsuboi K, Uyama T. Metabolism of endocannabinoids and related N-acylethanolamines: canonical and alternative pathways. FEBS J. 2013;280:1874–1894. doi: 10.1111/febs.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fezza F, Bari M, Florio R, Talamonti E, Feole M, Maccarrone M. Endocannabinoids, related compounds and their metabolic routes. Molecules. 2014;19:17078–17106. doi: 10.3390/molecules191117078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okamoto Y, Morishita J, Tsuboi K, Tonai T, Ueda N. Molecular characterization of a phospholipase D generating anandamide and its congeners. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5298–5305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cravatt BF, Giang DK, Mayfield SP, Boger DL, Lerner RA, Gilula NB. Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fatty-acid amides. Nature. 1996;384:83–87. doi: 10.1038/384083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei BQ, Mikkelsen TS, McKinney MK, Lander ES, Cravatt BF. A second fatty acid amide hydrolase with variable distribution among placental mammals. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36569–36578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuboi K, Sun YX, Okamoto Y, Araki N, Tonai T, Ueda N. Molecular characterization of N-acylethanolamine-hydrolyzing acid amidase, a novel member of the choloylglycine hydrolase family with structural and functional similarity to acid ceramidase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11082–11092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ueda N, Tsuboi K, Uyama T. N-acylethanolamine metabolism with special reference to N-acylethanolamine-hydrolyzing acid amidase (NAAA) Prog Lipid Res. 2010;49:299–315. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bisogno T, Howell F, Williams G, et al. Cloning of the first sn1-DAG lipases points to the spatial and temporal regulation of endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:463–468. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dinh TP, Freund TF, Piomelli D. A role for monoglyceride lipase in 2-arachidonoylglycerol inactivation. Chem Phys Lipids. 2002;121:149–158. doi: 10.1016/S0009-3084(02)00150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kozak KR, Crews BC, Morrow JD, et al. Metabolism of the endocannabinoids, 2-arachidonylglycerol and anandamide, into prostaglandin, thromboxane, and prostacyclin glycerol esters and ethanolamides. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44877–44885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozak KR, Crews BC, Ray JL, Tai HH, Morrow JD, Marnett LJ. Metabolism of prostaglandin glycerol esters and prostaglandin ethanolamides in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36993–36998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van der Stelt M, van Kuik JA, Bari M, et al. Oxygenated metabolites of anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol: conformational analysis and interaction with cannabinoid receptors, membrane transporter, and fatty acid amide hydrolase. J Med Chem. 2002;45:3709–3720. doi: 10.1021/jm020818q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen JK, Chen J, Imig JD, et al. Identification of novel endogenous cytochrome p450 arachidonate metabolites with high affinity for cannabinoid receptors. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:24514–24524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709873200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fowler CJ. Anandamide uptake explained? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fowler CJ. Transport of endocannabinoids across the plasma membrane and within the cell. FEBS J. 2013;280:1895–1904. doi: 10.1111/febs.12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehehalt R, Füllekrug J, Pohl J, Ring A, Herrmann T, Stremmel W. Translocation of long chain fatty acids across the plasma membrane – lipid rafts and fatty acid transport proteins. Mol Cell Biochem. 2006;284:135–140. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-9034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Pasquale E, Chahinian H, Sanchez P, Fantini J. The insertion and transport of anandamide in synthetic lipid membranes are both cholesterol-dependent. PLoS One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chicca A, Marazzi J, Nicolussi S, Gertsch J. Evidence for bidirectional endocannabinoid transport across cell membranes. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:34660–34682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.373241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dainese E, Oddi S, Bari M, Maccarrone M. Modulation of the endocannabinoid system by lipid rafts. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:2702–2715. doi: 10.2174/092986707782023235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oddi S, Fezza F, Pasquariello N, et al. Evidence for the intracellular accumulation of anandamide in adiposomes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:840–850. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7494-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maccarrone M, Bernardi G, Finazzi Agrò A, Centonze D. Cannabinoid receptor signalling in neurodegenerative diseases: a potential role for membrane fluidity disturbance. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:1379–1390. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01277.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Marzo V, De Petrocellis L. Endocannabinoids as regulators of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels: a further opportunity to develop new endocannabinoid-based therapeutic drugs. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:1430–1449. doi: 10.2174/092986710790980078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zygmunt PM, Ermund A, Movahed P, et al. Monoacylglycerols activate TRPV1—a link between phospholipase C and TRPV1. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pistis M, Melis M. From surface to nuclear receptors: the endocannabinoid family extends its assets. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:1450–1467. doi: 10.2174/092986710790980014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moriconi A, Cerbara I, Maccarrone M, Topai A. GPR55: current knowledge and future perspectives of a purported “type-3” cannabinoid receptor. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:1411–1429. doi: 10.2174/092986710790980069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross RA. L-α-lysophosphatidylinositol meets GPR55: a deadly relationship. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Marzo V, Stella N, Zimmer A. Endocannabinoid signalling and the deteriorating brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:30–42. doi: 10.1038/nrn3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ben-Shabat S, Fride E, Sheskin T, et al. An entourage effect: inactive endogenous fatty acid glycerol esters enhance 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol cannabinoid activity. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;353:23–31. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(98)00392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costa B, Comelli F, Bettoni I, Colleoni M, Giagnoni G. The endogenous fatty acid amide, palmitoylethanolamide, has anti-allodynic and anti-hyperalgesic effects in a murine model of neuropathic pain: involvement of CB(1), TRPV1 and PPARgamma receptors and neurotrophic factors. Pain. 2008;139:541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho WS, Barrett DA, Randall MD. “Entourage” effects of N-palmitoylethanolamine and N-oleoylethanolamine on vasorelaxation to anandamide occur through TRPV1 receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:837–846. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association, Arlington, VA, 2013.

- 37.Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S. ADOS, Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gotham K, Risi S, Pickles A, Lord C. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule: revised algorithms for improved diagnostic validity. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37:613–627. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0280-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rutter M, Le Couter A, Lord C. ADI-R, Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Persico AM. Autisms. In: Neural circuit development and function in the healthy and diseased brain: comprehensive developmental neuroscience, vol. 3 (Rakic P. and Rubenstein J, eds). Elsevier, New York, 2013, pp. 651-694.

- 41.Piven J, Palmer P, Jacobi D, Childress D, Arndt S. Broader autism phenotype: evidence from a family history study of multiple-incidence autism families. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:185–190. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R, Martin J, Clubley E. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31:5–17. doi: 10.1023/A:1005653411471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2010 Principal Investigators; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years – autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ 2014;63:1-21. [PubMed]

- 44.Ozonoff S, Young GS, Carter A, et al. Recurrence risk for autism spectrum disorders: a Baby Siblings Research Consortium study. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e488–e495. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elsabbagh M, Fernandes J, Jane Webb S, et al. Disengagement of visual attention in infancy is associated with emerging autism in toddlerhood. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chawarska K, Shic F, Macari S, et al. 18-month predictors of later outcomes in younger siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder: a baby siblings research consortium study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:1317–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gangi DN, Ibañez LV, Messinger DS. Joint attention initiation with and without positive affect: risk group differences and associations with ASD symptoms. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44:1414–1424. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-2002-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gliga T, Jones EJ, Bedford R, Charman T, Johnson MH. From early markers to neuro-developmental mechanisms of autism. Dev Rev. 2014;34:189–207. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tuchman R, Rapin I. Epilepsy in autism. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:352–358. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(02)00160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fombonne E. Epidemiology of autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Souders MC, Mason TB, Valladares O, et al. Sleep behaviors and sleep quality in children with autism spectrum disorders. Sleep. 2009;32:1566–1578. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.12.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tarazi F, Sahli Z, Pleskow J, Mousa S. Asperger’s syndrome: diagnosis, comorbidity and therapy. Expert Rev Neurother. 2015;15:281–293. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2015.1009898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Di Cicco-Bloom E, Lord C, Zwaigenbaum L, et al. The developmental neurobiology of autism spectrum disorder. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6897–6906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1712-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amaral DG, Schumann CM, Nordahl CW. Neuroanatomy of autism. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blatt GJ. The neuropathology of autism. Scientifica. 2012;2012:703675. doi: 10.6064/2012/703675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bauman ML, Kemper TL. Neuroanatomic observations of the brain in autism: a review and future directions. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rice D, Barone S., Jr Critical periods of vulnerability for the developing nervous system: evidence from humans and animal models. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl. 3):511–533. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Geschwind DH, Levitt P. Autism spectrum disorders: developmental disconnection syndromes. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hahamy A, Behrmann M, Malach R. The idiosyncratic brain: distortion of spontaneous connectivity patterns in autism spectrum disorder. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:302–309. doi: 10.1038/nn.3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Geschwind DH. Genetics of autism spectrum disorders. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Persico AM, Napolioni V. Autism genetics. Behav Brain Res. 2013;251:95–112. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Persico AM, Merelli S. Environmental factors and autism spectrum disorder. Curr Dev Disord Rep. 2014;1:8–19. doi: 10.1007/s40474-013-0002-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tordjman S, Somogyi E, Coulon N, et al. Gene × environment interactions in autism spectrum disorders: role of epigenetic mechanisms. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:53. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vargas DL, Nascimbene C, Krishnan C, Zimmerman AW, Pardo CA. Neuroglial activation and neuroinflammation in the brain of patients with autism. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:67–81. doi: 10.1002/ana.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garbett KA, Ebert PJ, Mitchell A, et al. Immune transcriptome alterations in the temporal cortex of subjects with autism. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lintas C, Sacco R, Persico AM. Genome-wide expression studies in Autism spectrum disorder, Rett syndrome, and Down syndrome. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;45:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sacco R, Curatolo P, Manzi B, et al. Principal pathogenetic components and biological endophenotypes in autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res. 2010;3:237–252. doi: 10.1002/aur.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fox E, Amaral D, Van de Water J. Maternal and fetal antibrain antibodies in development and disease. Dev Neurobiol. 2012;72:1327–1334. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Onore C, Careaga M, Ashwood P. The role of immune dysfunction in the pathophysiology of autism. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McElhanon BO, McCracken C, Karpen S, Sharp WG. Gastrointestinal symptoms in autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2014;133:872–883. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Piras I, Haapanen L, Napolioni V, Sacco R, Van de Water J, Persico A. Anti-brain antibodies are associated with more severe cognitive and behavioural profiles in Italian children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;38:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chakrabarti B, Baron-Cohen S. Empathizing: neurocognitive developmental mechanisms and individual differences. Prog Brain Res. 2006;156:403–417. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)56022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chevallier C, Kohls G, Troiani V, Brodkin ES, Schultz RT. The social motivation theory of autism. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sims TB, Van Reekum CM, Johnstone T, Chakrabarti B. How reward modulates mimicry: EMG evidence of greater facial mimicry of more rewarding happy faces. Psychophysiology. 2012;49:998–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2012.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sims TB, Neufeld J, Johnstone T, Chakrabarti B. Autistic traits modulate frontostriatal connectivity during processing of rewarding faces. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9:2010201–2010206. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsu010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dawson G, Carver L, Meltzoff AN, Panagiotides H, McPartland J, Webb SJ. Neural correlates of face and object recognition in young children with autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, and typical development. Child Dev. 2002;73:700–717. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pierce K, Conant D, Hazin R, Stoner R, Desmond J. Preference for geometric patterns early in life as a risk factor for autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:101–109. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schmitz N, Rubia K, van Amelsvoort T, Daly E, Smith A, Murphy DG. Neural correlates of reward in autism. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:19–24. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dichter GS, Richey JA, Rittenberg AM, Sabatino A, Bodfish JW. Reward circuitry function in autism during face anticipation and outcomes. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:147–160. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1221-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kohls G, Schulte-Rüther M, Nehrkorn B. Reward system dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2013;8:565–572. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Demurie E, Roeyers H, Baeyens D, Sonuga-Barke E. Common alterations in sensitivity to type but not amount of reward in ADHD and autism spectrum disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52:1164–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dawson G, Bernier R, Ring RH. Social attention: a possible early indicator of efficacy in autism clinical trials. J Neurodev Disord. 2012;4:11. doi: 10.1186/1866-1955-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fletcher-Watson S, Leekam SR, Benson V, Frank MC, Findlay JM. Eye-movements reveal attention to social information in autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klin A, Jones W, Schultz R, Volkmar F, Cohen D. Visual fixation patterns during viewing of naturalistic social situations as predictors of social competence in individuals with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:809–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sasson NJ, Dichter GS, Bodfish JW. Affective responses by adults with autism are reduced to social images but elevated to images related to circumscribed interests. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Krajbich I, Armel C, Rangel A. Visual fixations and the computation and comparison of value in simple choice. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1292–1298. doi: 10.1038/nn.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stavropoulos KK, Carver LJ. Effect of familiarity on reward anticipation in children with and without autism spectrum disorders. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Richey JA, Rittenberg A, Hughes L, et al. Common and distinct neural features of social and non-social reward processing in autism and social anxiety disorder. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9:367–377. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chakrabarti B, Bullmore E, Baron-Cohen S. Empathizing with basic emotions: common and discrete neural substrates. Soc Neurosci. 2006;1:364–384. doi: 10.1080/17470910601041317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ruggeri B, Sarkans U, Schumann G, Persico AM. Biomarkers in autism spectrum disorder: the old and the new. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:1201–1216. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3290-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vorstman JA, Spooren W, Persico AM, et al. Using genetic findings in autism for the development of new pharmaceutical compounds. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:1063–1078. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3334-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Battista N, Bari M, Tarditi A, et al. Severe deficiency of the fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) activity segregates with the Huntington's disease mutation in peripheral lymphocytes. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;27:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Centonze D, Battistini L, Maccarrone M. The endocannabinoid system in peripheral lymphocytes as a mirror of neuroinflammatory diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:2370–2382. doi: 10.2174/138161208785740018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Marco EM, Scattoni ML, Rapino C, et al. Emotional, endocrine and brain anandamide response to social challenge in infant male rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:2152–2162. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sciolino NR, Bortolato M, Eisenstein SA, et al. Social isolation and chronic handling alter endocannabinoid signaling and behavioral reactivity to context in adult rats. Neuroscience. 2010;168:371–386. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Marco EM, Rapino C, Caprioli A, Borsini F, Maccarrone M, Laviola G. Social encounter with a novel partner in adolescent rats: activation of the central endocannabinoid system. Behav Brain Res. 2011;220:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bagni C, Tassone F, Neri G, Hagerman R. Fragile X syndrome: causes, diagnosis, mechanisms, and therapeutics. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4314–4322. doi: 10.1172/JCI63141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ludwig AL, Espinal GM, Pretto DI, et al. CNS expression of murine fragile X protein (FMRP) as a function of CGG-repeat size. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:3228–3238. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gürkan CK, Hagerman RJ. Targeted treatments in autism and Fragile X syndrome. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2012;6:1311–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maccarrone M, Rossi S, Bari M, et al. Abnormal mGlu 5 receptor/endocannabinoid coupling in mice lacking FMRP and BC1 RNA. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1500–1509. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jung KM, Sepers M, Henstridge CM, et al. Uncoupling of the endocannabinoid signalling complex in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1080. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Busquets-Garcia A, Gomis-González M, Guegan T, et al. Targeting the endocannabinoid system in the treatment of fragile X syndrome. Nat Med. 2013;19:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nm.3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schultz ST. Can autism be triggered by acetaminophen activation of the endocannabinoid system? Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2010;70:227–231. doi: 10.55782/ane-2010-1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kerr DM, Downey L, Conboy M, Finn DP, Roche M. Alterations in the endocannabinoid system in the rat valproic acid model of autism. Behav Brain Res. 2013;249:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liu QR, Pan CH, Hishimoto A, et al. Species differences in cannabinoid receptor 2 (CNR2 gene): identification of novel human and rodent CB2 isoforms, differential tissue expression and regulation by cannabinoid receptor ligands. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:519–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00498.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Onaivi ES, Benno R, Halpern T, et al. Consequences of cannabinoid and monoaminergic system disruption in a mouse model of autism spectrum disorders. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9:209–214. doi: 10.2174/157015911795017047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Siniscalco D, Sapone A, Giordano C, et al. Cannabinoid receptor type 2, but not type 1, is up-regulated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of children affected by autistic disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43:2686–2695. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1824-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Depino AM. Peripheral and central inflammation in autism spectrum disorders. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2013;53:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Leleu-Chavain N, Desreumaux P, Chavatte P, Millet R. Therapeutical potential of CB2 receptors in immune-related diseases. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2013;6:183–203. doi: 10.2174/1874467207666140219122337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rom S, Persidsky Y. Cannabinoid receptor 2: potential role in immunomodulation and neuroinflammation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:608–620. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9445-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chiurchiù V, Battistini L, Maccarrone M. Endocannabinoid signaling in innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol. 2015;144:352–364. doi: 10.1111/imm.12441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cencioni MT, Chiurchiù V, Catanzaro G, et al. Anandamide suppresses proliferation and cytokine release from primary human T-lymphocytes mainly via CB2 receptors. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Brown I, Cascio MG, Rotondo D, Pertwee RG, Heys SD, Wahle KW. Cannabinoids and omega-3/6 endocannabinoids as cell death and anticancer modulators. Prog Lipid Res. 2013;52:80–109. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Das U. Autism as a disorder of deficiency of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and altered metabolism of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Nutrition. 2013;29:1175–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Van der Stelt M, Di Marzo V. The endocannabinoid system in the basal ganglia and in the mesolimbic reward system: implications for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;480:133–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chakrabarti B, Kent L, Suckling J, Bullmore E, Baron-Cohen S. Variations in the human cannabinoid receptor (CNR1) gene modulate striatal responses to happy faces. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:1944–1948. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Domschke K, Dannlowski U, Ohrmann P, et al. Cannabinoid receptor 1 (CNR1) gene: impact on antidepressant treatment response and emotion processing in major depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18:751–759. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chakrabarti B, Baron-Cohen S. Variation in the human cannabinoid receptor CNR1 gene modulates gaze duration for happy faces. Mol Autism. 2011;2:10. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Chakrabarti B, Dudbridge F, Kent L, et al. Genes related to sex steroids, neural growth, and social–emotional behavior are associated with autistic traits, empathy, and Asperger syndrome. Autism Res. 2009;2:157–177. doi: 10.1002/aur.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S. The empathy quotient: an investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. J Autism Dev Disord. 2004;34:163–175. doi: 10.1023/B:JADD.0000022607.19833.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Purcell AE, Jeon OH, Zimmerman AW, Blue ME, Pevsner J. Postmortem brain abnormalities of the glutamate neurotransmitter system in autism. Neurol. 2001;57:1618–1628. doi: 10.1212/WNL.57.9.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Trezza V, Vanderschuren LJ. Bidirectional cannabinoid modulation of social behavior in adolescent rats. Psychopharmacol. 2008;197:217–227. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Trezza V, Baarendse PJ, Vanderschuren LJ. The pleasures of play: pharmacological insights into social reward mechanisms. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Maccarrone M, Guzmán M, Mackie K, Doherty P, Harkany T. Programming of neural cells by (endo)cannabinoids: from physiological rules to emerging therapies. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:786–801. doi: 10.1038/nrn3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Belmonte MK, Allen G, Beckel-Mitchener A, Boulanger LM, Carper RA, Webb SJ. Autism and abnormal development of brain connectivity. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9228–9231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3340-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Persico AM, Bourgeron T. Searching for ways out of the autism maze: genetic, epigenetic and environmental clues. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Spooren W, Lindemann L, Ghosh A, Santarelli L. Synapse dysfunction in autism: a molecular medicine approach to drug discovery in neurodevelopmental disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:669–684. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tsai NP, Wilkerson JR, Guo W, et al. Multiple autism-linked genes mediate synapse elimination via proteasomal degradation of a synaptic scaffold PSD-95. Cell. 2012;151:1581–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Bourgeron T. A synaptic trek to autism. Current Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:231–234. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Jaramillo TC, Liu S, Pettersen A, Birnbaum SG, Powell CM. Autism-related neuroligin-3 mutation alters social behavior and spatial learning. Autism Res. 2014;7:264–272. doi: 10.1002/aur.1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Földy C, Malenka RC, Südhof TC. Autism-associated neuroligin-3 mutations commonly disrupt tonic endocannabinoid signaling. Neuron. 2013;78:498–509. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cota D, Steiner MA, Marsicano G, et al. Requirement of cannabinoid receptor type 1 for the basal modulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function. Endocrinol. 2007;148:1574–1581. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Atkinson HC, Leggett JD, Wood SA, Castrique ES, Kershaw YM, Lightman SL. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis circadian rhythm by endocannabinoids is sexually diergic. Endocrinol. 2010;15:3720–3727. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Vaughn LK, Denning G, Stuhr KL, de Wit H, Hill MN, Hillard CJ. Endocannabinoid signalling: has it got rhythm? Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:530–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00790.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Glickman G. Circadian rhythms and sleep in children with autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34:755–768. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Melke J, Goubran Botros H, Chaste P. Abnormal melatonin synthesis in autism spectrum disorders. Mol Psychiat. 2008;13:90–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Campos AC, Guimarães FS. Involvement of 5HT1A receptors in the anxiolytic-like effects of cannabidiol injected into the dorsolateral periaqueductal gray of rats. Psychopharmacology. 2008;199:223–230. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Rubino T, Guidali C, Vigano D, et al. CB1 receptor stimulation in specific brain areas differently modulate anxiety-related behaviour. Neuropharmacol. 2008;54:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Katona I, Freund TF. Endocannabinoid signaling as a synaptic circuit breaker in neurological disease. Nat Med. 2008;14:923–930. doi: 10.1038/nm.f.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Sasso O, Migliore M, Habrant D, et al. Multitarget fatty acid amide hydrolase/cyclooxygenase blockade suppresses intestinal inflammation and protects against nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug dependent gastrointestinal damage. FASEB J. 2015;29:2616–2627. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-270637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Arosio B, D’Addario C, Gussago C, et al. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) as a laboratory to study dementia in the elderly. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:169203. doi: 10.1155/2014/169203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 506 kb)