Abstract

Cannabis has been used for centuries to treat seizures. Recent anecdotal reports, accumulating animal model data, and mechanistic insights have raised interest in cannabis-based antiepileptic therapies. In this study, we review current understanding of the endocannabinoid system, characterize the pro- and anticonvulsive effects of cannabinoids [e.g., Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol (CBD)], and highlight scientific evidence from pre-clinical and clinical trials of cannabinoids in epilepsy. These studies suggest that CBD avoids the psychoactive effects of the endocannabinoid system to provide a well-tolerated, promising therapeutic for the treatment of seizures, while whole-plant cannabis can both contribute to and reduce seizures. Finally, we discuss results from a new multicenter, open-label study using CBD in a population with treatment-resistant epilepsy. In all, we seek to evaluate our current understanding of cannabinoids in epilepsy and guide future basic science and clinical studies.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13311-015-0375-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Epilepsy, seizures, cannabinoids, cannabidiol, THC, cannabis

Introduction

Epilepsy affects 2.9 million people in the USA and 65 million people worldwide (cdc.gov/epilepsy). One in 26 people in the USA will develop epilepsy in their lifetime [1]. Characterized by recurrent seizures, epilepsy encompasses multiple disorders caused by varied etiologies, including genetic syndromes, stroke, infection, and traumatic brain injury. Many patients with epilepsy also have sensorimotor, cognitive, psychological, psychiatric, and social impairments, as well as impaired quality of life and an increased risk of premature death [1]. While epilepsy can affect patients of all ages, it most commonly affects children, the elderly, and individuals with low socioeconomic status. The estimated direct and indirect annual cost of epilepsy in the U.S. is $15.5 billion (cdc.gov/epilepsy).

While many drugs can limit seizures, no drug can prevent the underlying cause of epilepsy or the development of epilepsy (epileptogenesis) in patients who are at risk (e.g., after head trauma). A third of patients remain pharmacoresistant, failing to achieve sustained seizure freedom after 2 or more adequately chosen, tolerated, and appropriately used antiepileptic drugs (AEDs; more accurately termed antiseizure drugs) [2–4]. Patients resistant to multiple AEDs have an increased risk for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy and other forms of epilepsy-related mortality [5, 6], as well as impairments in psychosocial, behavioral, and cognitive functions [3, 7–9]. For many patients, epilepsy is a progressive disorder associated with ongoing loss of brain tissue and function. Finally, multidrug combinations and high dosages cause more severe side effects, a particular problem in patients with treatment-resistant epilepsies. Assessing the side effects of AEDs is especially challenging in patients on long-term AEDs as any ‘baseline’ may be many years past and even intelligent adults, parents, and physicians may fail to appreciate chronic adverse effects. The available AEDs fail to meet the clinical needs for both efficacy and safety [10], indicating a dire need for novel therapeutics that are targeted, disease-, and age-specific.

Recently, mounting anecdotal reports and media coverage have sparked intense interest among parents, patients, and the scientific community regarding the potential of medical cannabis to treat seizures. A potential alternative or supplement to current AEDs, the cannabis plant includes >100 diverse phytocannabinoids that, in part, target an endogenous endocannabinoid signaling network, as well as other networks. Two major phytocannabinoids derived from cannabis are psychoactive Δ9- tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and nonpsychoactive cannabidiol (CBD). Both Δ9-THC and CBD can prevent seizures and reduce mortality in animal models of seizure with low toxicity and high tolerability [11]. However, a systematic analysis from the American Academy of Neurology and a Cochrane Database review both concluded that medical cannabis is of “unknown efficacy” to treat epilepsy [12, 13]. In this review, we examine the history of cannabinoids in epilepsy, discuss the effectiveness of pre clinical seizure model studies with cannabinoids, and review recent clinical data, including a multicenter clinical trial of CBD for patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy.

History of Cannabis in Epilepsy

Cannabis has been used for millennia for medical, recreational, and manufacturing purposes. Around 2900 BCE, the Chinese Emperor Fu Hsi characterized cannabis as having sacred yin (weak, passive forces) and yang (strong, active forces) features, suggesting that it could restore homeostasis to an unbalanced body. Physicians in ancient India, Egypt, Persia, Rome, Arabia, and Greece used cannabis for spiritual and medicinal purposes, including menstrual fatigue, gout, rheumatism, malaria, beriberi, constipation, pain, and absentmindedness [14]. Early documented uses of cannabis to treat seizures include a Sumerian text from 2900 BCE and an Arabian document from the twelfth century [15, 16].

The 1854, the US Dispensatory listed cannabis to treat neuralgia, depression, pain, muscle spasms, insomnia, tetanus, chorea, insanity, and other disorders [17]. Cannabis was valued for its analgesic, anti-inflammatory, appetite-stimulating, and antibiotic properties. In the mid-1800s, the British surgeon William O’Shaughnessy reported cannabis therapy for the treatment of epilepsy, recounting an “alleviation of pain in most, a remarkable increase of appetite in all, unequivocal aphrodisia, and great mental cheerfulness” [14, 18]. Two of England’s most prominent mid-to-late nineteenth- century neurologists, J.R. Reynolds and W. Gowers, also noted the benefits of cannabis in epilepsy [19]. Gowers reported a man who previously failed bromides whose seizures were controlled on 9.8 g of Cannabis indica, dosed 3 times daily for up to 6 months [20].

Cannabis was first regulated in the USA with the 1906 “Pure Food and Drug Act”. The follow-up 1937 Marijuana Tax Act was opposed by the American Medical Association, which considered the more severe restrictions an infringement on physician’s freedom to treat patients [17]. In 1970, the US Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act categorized marijuana as a Schedule I drug with high potential for abuse and no accepted medicinal use. Legislation has been introduced to the US Senate to change marijuana to a Schedule II drug.

Over the last 50 years, the main chemical constituents of cannabis have been isolated and synthesized. Δ9-THC was isolated in 1964 and synthesized in 1971 [21, 22]. CBD was isolated in 1940 and synthesized in 1963 [23, 24]. The cannabinoid type 1 (CB1R) and type 2 (CB2R) receptors, which bind Δ9-THC, were cloned in the 1990s [25, 26], supporting an endogenous system for this principal cannabinoid’s pharmacological activity.

The Endocannabinoid System

The discovery of the endocannabinoid system in the early 1990s revealed the neuronal mechanisms that underlie the psychoactive effects of Δ9-THC in cannabis. Initial studies demonstrated that brief postsynaptic depolarization reduced neurotransmitter release from excitatory terminals onto Purkinje cells in the cerebellum and inhibitory terminals onto pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus [27, 28]. This phenomenon was termed “depolarization-induced suppression of excitation/inhibition” (DSE and DSI, respectively). Postsynaptic depolarization was postulated to trigger the release of an undiscovered substance that transiently limited presynaptic neurotransmitter release. Along with the discovery of nitric oxide (NO), this paradigm-shifting view suggested the concept of retrograde signaling in contrast to a primarily anterograde view of synaptic signaling. Application of a CB1R agonist (or antagonist) enhanced (or prevented) DSE and DSI, suggesting that it was mediated by an endogenous cannabinoid ligand [29–31]. These endocannabinoids were identified as the hydrophobic ligands N-arachidonoyl ethanolamide (anandamide) [32] and 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG) [33, 34].

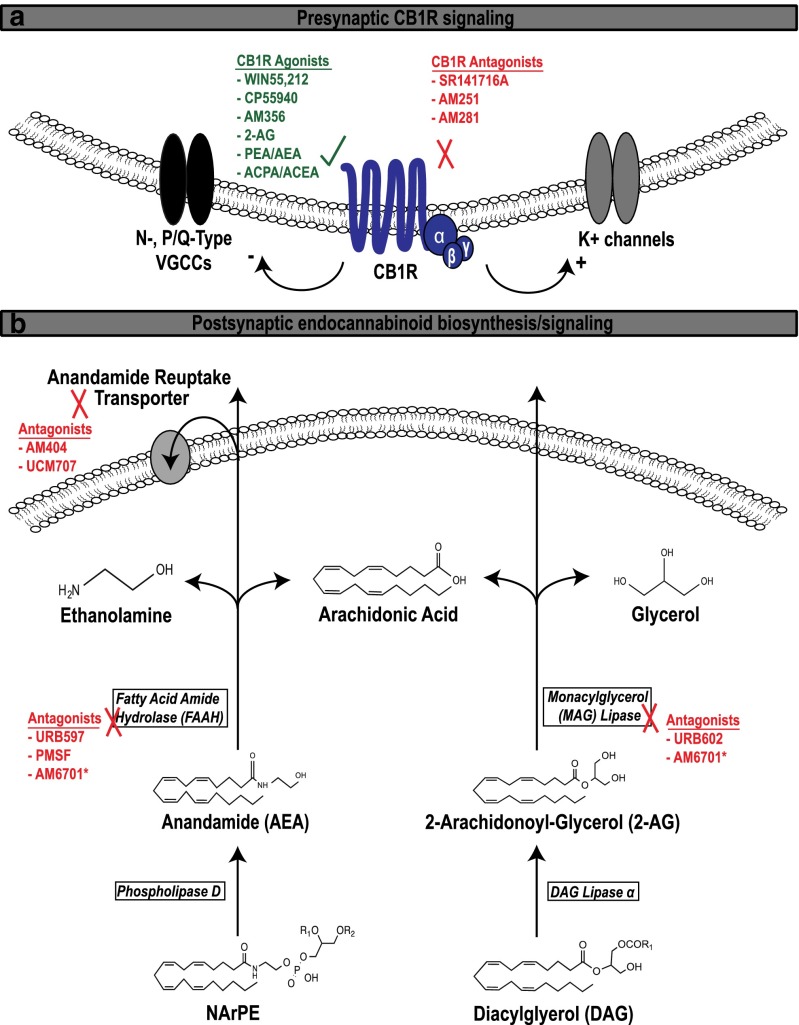

Anandamide and 2-AG are synthesized from postsynaptic membrane phospholipid precursors and released in an activity-dependent, “on-demand” manner, unlike traditional vesicular neurotransmitters (Fig. 1). Depolarization of the postsynaptic cell or direct activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors increases levels of intracellular calcium, which trigger second messenger cascades that promote endocannabinoid synthesis [35–39]. Anandamide is synthesized via phospholipase D-mediated hydrolysis of N-arachidonoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine, and degraded by the fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) into arachidonic acid and ethanolamine [40–43]. 2-AG is synthesized via diacylglycerol (DAG) lipase (DAGL) α-mediated hydrolysis of DAG, and degraded by FAAH into arachidonic acid and glycerol, or by monoacylglycerol lipase [41–44]. Chronic hyperexcitability leads to dynamic changes in the endocannabinoid pathway (see “The Endocannabinoid System: CB1Rs”). Thus, the enzymes that regulate metabolism and cannabinoid receptors represent attractive targets to treat several neurological disorders [45]. Accordingly, the selective CB1R blocker rimonabant was approved in >50 countries as an anorectic to treat obesity [46], and showed promise in helping smokers quit tobacco use [47], but its use was suspended when postmarketing surveillance revealed high rates of depression and suicidal ideation.

Fig. 1.

Biosynthesis, degradation, and signaling of endocannabinoids. (A) Presynaptic cannabinoid type 1 receptor (CB1R) signaling. (B) Postsynaptic endocannabinoid biosynthesis/signaling. NArPE = N-arachidonoyl phosphatidylethanolamine; DAG = 1-acyl, 2-arachidonoyl diacylglycerol; VGCC = voltage-gated calcium channels; PEA = palmitoylethanolamide; ACPA = arachidonylcyclopropylamide; ACEA = arachidonyl-2'-chloroethylamide; PMSF = phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

Produced in an activity-dependent manner, endocannabinoids travel to the presynaptic cell and bind to CB1Rs. CB1Rs are G protein-coupled receptors linked to pertussis-sensitive Gi/o α subunits. Activation of the α subunit triggers dissociation of the βγ complex, which reduces adenylate cyclase production of cyclic adenosine monophosphate [48], inhibits N- and P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channels [31, 49–52], stimulates A-type potassium channels [53–56], activates G protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channels [57–59], and inhibits the vesicular release machinery [60]. These multiple mechanisms reduce presynaptic cell excitability and Ca2+, strongly diminishing presynaptic neurotransmitter release. CB1Rs can also regulate the presynaptic release of multiple neuromodulators such as acetylcholine, dopamine, and norepinephrine [61]. Finally, endocannabinoid signaling may modulate regional-specific long-term synaptic plasticity, including long-term potentiation and long-term depression (for a review, see [62, 63]).

CB1Rs are distributed primarily in axon terminals in the neocortex (especially cingulate, frontal, and parietal regions), hippocampus, amygdala, basal ganglia, thalamus, hypothalamus, nucleus accumbens, substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area, cerebellum, and brainstem [39]. CB1Rs are most densely expressed at cortical and hippocampal presynaptic γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic presynaptic boutons, especially cholecystokinin-positive (CCK+) and parvalbumin-negative GABAergic interneurons [64–66]. Glutamatergic axon terminals in cortical and subcortical neurons contain fewer presynaptic CB1 receptors than GABAergic terminals [65, 67–71].

Phytocannabinoids: Classification and Function

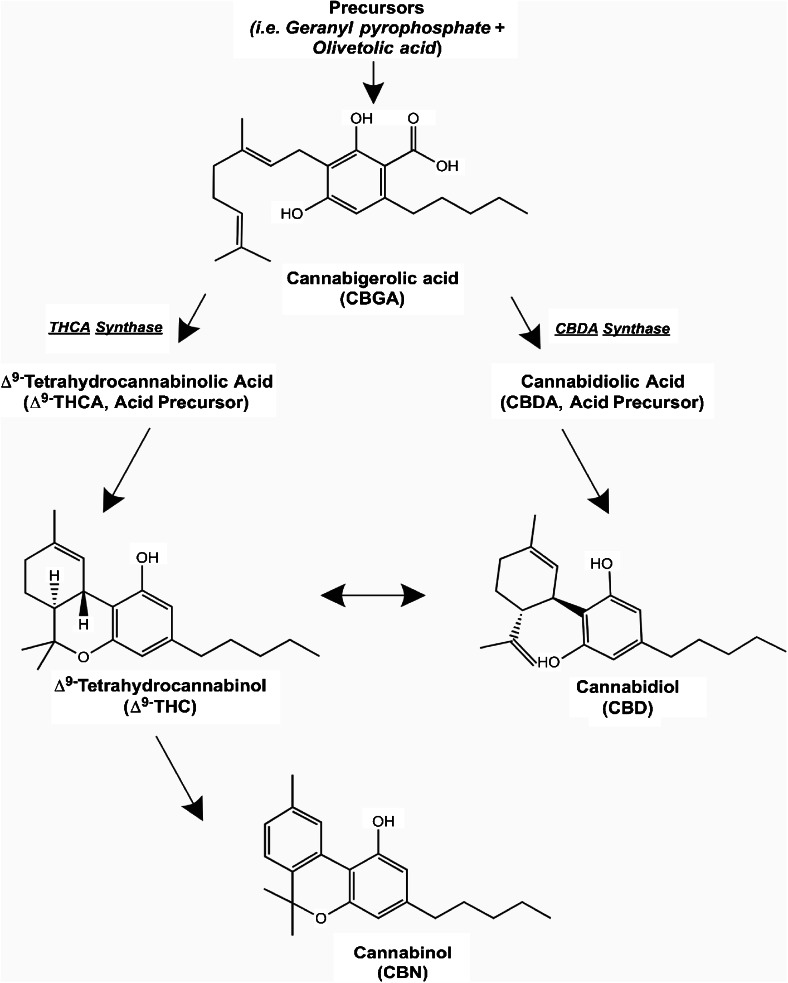

The cannabis plant consists contains >100 C21 terpenophenolic compounds, known collectively as phytocannabinoids [72]. Most of these lipophilic cannabinoids are closely related and differ only by a single chemical functional group. Cannabinoids fall into 10 main groups, with constituents representing degradation products, precursors, or byproducts (Fig. 2, adapted from [73]). Two of the most abundant constituents are Δ9-THC and CBD, the ratios of which vary by cannabis strain. Cannabis sativa contains a higher ratio of Δ9-THC to CBD, producing more stimulating, psychotropic effects. Cannabis indica strains contains a higher ratio of CBD:Δ9-THC and are typically more sedating [11, 73].

Fig. 2.

Biosynthesis of phytocannabinoids [73]

Δ9-THC

Δ9-THC is a partial agonist at central nervous system (CNS) CB1Rs and CB2Rs in the immune system. Most behavioral, cognitive, and psychotropic effects of cannabis result from the effects of Δ9-THC at brain CB1Rs. The subjective “high” produced by cannabis can be blocked by pretreatment with the CB1R antagonist rimonabant [74]. Δ9-THC impairs short-term working memory in several rodent models, which can be reversed by preapplication of a CB1R antagonist [75–78]. Inhibition of long-term potentiation at hippocampal CA3 Schaffer Collateral/CA1 synapses may underlie this effect on memory [35]. Δ9-THC or CB1R agonists can increase or decrease food intake in different species [79]. Δ9-THC also regulates neuronal excitability during seizures (see “Preclinical Evidence”). Thus, Δ9-THC acts through the endocannabinoid system to regulate mood, learning and memory, neuronal excitability, and energy balance. Δ9-THC exerts potent anti-inflammatory functions via CB1Rs and CB2Rs on microglia, the primary immune cells in the CNS. Δ9-THC or CB1R agonists limit neurotoxicity in in vitro and in vivo assays, including chemotoxic [80–83], low Mg2+ [84], and ischemic [85, 86] models. Δ9-THC has antioxidant effects in α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid- and N-methyl-D-aspartate-mediated cytotoxicity models via a CB1R-independent mechanism [87]. Cannabinoids reduce neuronal and glial release of the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α, NO, interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6 [88–93], and increase release of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-10, and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1a) [94, 95] via CB1R- and CB2R-dependent mechanisms in neurons and glia [94, 95] (reviewed in [96]). Δ9-THC also transiently activates and desensitizes the transient receptor potential (TRP) channels TRPA1, TRPV1, and TRPV2 [97–99]. Given the synergistic relation between seizures and inflammation [100–102], the cannabinoid system provides a novel strategy to target both segments of this feedback cycle.

CBD

CBD resembles Δ9-THC structurally but the 2 molecules differ significantly in pharmacology and function. CBD has very low affinity at CB1R and CB2R, unlike Δ9-THC [103–106]. The potential targets for CBD are reviewed in detail in another article in this issue (“Molecular Targets of CBD in Neurological Disorders”). CBD is an agonist at TRP channels (TRPV1, TRPV2, TRPA1) [98, 99, 104], 5-hydroxytryptamine1α receptors [107], and glycine receptors [108]. CBD is an antagonist at TRP melastatin type-8 channels [97], T-type voltage-gated calcium channels [109], and G protein-coupled-receptor GPR55 (see below).

CBD exerts dynamic control over intracellular calcium stores through multiple, activity-dependent pathways [110, 111]. CBD induces a bidirectional change in intracellular calcium levels that depends on cellular excitability. Under normal physiological Ca2+ conditions, CBD slightly increases intracellular Ca2+, whereas CBD reduces intracellular Ca2+under high-excitability conditions. These changes were blocked by the pretreatment with an antagonist of the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, suggesting a mitochondrial site of action [111]. CBD also produces biphasic changes in intracellular calcium levels via antagonism of the mitochondrial voltage-dependent anion channel 1 [112].

CBD antagonizes GPR55, which functions as a counterpart to the canonical CB1R/CB2R signaling pathway [113]. GPR55 is present in the caudate, putamen, hippocampus, thalamus, pons, cerebellum, frontal cortex, and thalamus. GPR55 was initially characterized as a novel cannabinoid receptor, coupled to Gα13 [114]. Activation of GPR55 in human embryonic kidney cells triggers the release of intracellular Ca2+ from endoplasmic reticulum stores via a pathway dependent on RhoA (Ras homolog gene family member A), phospholipase C, and inositol 1,4.5-trisphosphate receptor [115]. The endogenous membrane phospholipid L-α-lysophosphatidylinositol is a GPR55 agonist [116]. Brief application of L-α-lysophosphatidylinositol transiently increases intracellular Ca2+ levels and vesicular release probability at excitatory hippocampal synapses. CBD opposes this effect by reducing glutamate release, suggesting a potential antiseizure mechanism [117]. CBD also reduces epileptiform activity (burst amplitude and duration) in in vitro (4-aminopyridine and Mg2+) models through a CB1-independent, concentration-dependent, and region-specific manner in the hippocampus. Preclinical studies demonstrate an antiseizure effect of CBD (see “Preclinical Evidence”).

CBD also regulates several transporters, enzymes, and metabolic pathways that are common to Δ9-THC and endocannabinoid signaling. CBD inhibits uptake of adenosine by blocking the equilibrative nucleoside transporter [118, 119]. Increased levels of adenosine activate A2 receptors, which regulate striatal CB1Rs [120]. At high micromolar levels, CBD also inhibits the uptake and enzymatic degradation of anandamide via FAAH, elevating anandamide extracellular concentrations [121]. Thus, dynamic interactions likely occur between the multiple plant cannabinoids such as CBD and Δ9-THC (see “Entourage Effect”).

CBD limits inflammation and oxidative stress [122]. CBD reduces oxidative toxicity in an in vitro glutamate excitotoxicity assay [123], and raises adenosine to oppose lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and tumor necrosis factor-α release [118, 124]. In mice with middle cerebral artery occlusion, CBD triggered a CB1R-independent decrease in reperfusion injury, inflammation, and death. This neuroprotective action may result from reduced myeloperoxidase activity, neutrophil migration, and microglia high-mobility group box 1 expression [125, 126]. Additionally, CBD activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, reduces NO and IL-β release, limits gliosis, and restricts neuroinflammation in mice injected with amyloid β [127–129]. Finally, treatment of microglial cultures with interferon-γ raised mRNA levels of the CBD receptor GPR55 [130], which regulates the inflammatory responses to neuropathic pain [131]. Taken together, these studies suggest that CBD reduces neuroinflammation in several disease-specific conditions.

The “Entourage Effect”

The “entourage effect” was a term originally coined by Ben-Shabat et al. [132] to refer to the potentiating effects of endocannabinoid metabolic byproducts on endocannabinoid function at CB1Rs and CB2Rs. They observed that 2 esters of the endocannabinoid 2-AG—s2-linoleoyl-glycerol and 2-palmitoyl-glycerol—were present in spleen, brain, and gut, together with 2-AG. While these esters do not bind to cannabinoid receptors or inhibit adenylyl cyclase via either CB1 or CB2, each ester potentiated 2-AG-induced inhibition of motor behavior, immobility on a ring, analgesia on a hot plate, and hypothermia: behavioral tests commonly referred to as the ‘tetrad’ by which CB1-mediated effects can be detected [132]. Thus, the original concept of the entourage effect referred to a specific group of endogenous compounds, structurally similar to endocannabinoids, that potentiated the effects of endogenous cannabinoid receptor agonists at CB1Rs and CB2Rs.

Subsequently, the idea of the entourage effect has expanded considerably both with regard to mechanisms of interactions, as well as classes of chemical agents. The diversification of entourage effects has been promoted by scientific and lay authors, and often well beyond its original boundaries. Wagner and Ulrich-Merzenich [133] proposed 4 potential mechanisms of synergy for phytotherapeutics, using cannabis as an exemplar: 1) multitarget effects; 2) pharmacokinetic effects (e.g., improved bioavailability or solubility); 3) improved bacterial resistance; and 4) modulation of adverse events (AEs; truly an antagonism, albeit a beneficial one) [133]. This approach thereby extended the tightly defined entourage effect to include practically any plant mixture acting through any molecular target to exert any effect.

The cannabis plant contains a complex mixture of both cannabinoids (i.e., Δ9-THC and CBD) and terpenoids (limonene, myrcene, α-pinene, linalool, β-caryophyllene, caryophyllene oxide, nerolidol, and phytol) derived from a common precursor (geranyl pyrophosphate). Several studies posited that the “entourage” of “[whole] plants are better drugs than the natural products isolated from them”, suggesting that the clinical effects of cannabis usage may be due to complex interactions between several plant cannabinoids [134, 135]. In support of this view, CBD may potentiate the beneficial effects associated with Δ9-THC (analgesia, antiemesis, and anti-inflammation) and reduce the negative psychoactive effects of Δ9-THC (impaired working memory, sedation, tachycardia, and paranoia) [136–138]. Users of cannabis with a high CBD:Δ9-THC ratio have greater tolerability and lower rates of psychosis than users of high Δ9-THC:CBD ratios (or Δ9-THC alone) [139]. Additional reports claim potential synergistic interactions of phytocannabinoids and phytoterpenoids that may include therapeutic effects on pain, inflammation, depression, anxiety, addiction, epilepsy, cancer, fungal, and bacterial infections [135, 140]. However, proper characterization of any “synergistic” effects of multiple plant cannabinoids requires statistically robust demonstrations of effects greater than the sum of the parts. These effects can be tested in vitro or in vivo using assays such as the isobolographic approach [141, 142]. Such a design can show if any 2 compounds, extracts, or mixtures are additive in the specific assay (e.g., models of seizure), synergistic, or antagonistic, thereby avoiding speculation about potential synergism or the confusion of additive effects with synergism. Although experimental data support the efficacy of both CBD and Δ9-THC as individual agents in various animal models of epilepsy, we are not aware of any studies demonstrating synergy of these compounds in animal models nor any controlled trials that establish a synergistic effect in patients with epilepsy.

Collectively, several studies demonstrate functional (but not defined molecular) interactions between plant cannabinoids that extended the initial concept of the entourage effect far beyond its original intent. While such interactions may exist, further well-defined research is required to verify anecdotal claims regarding the increased antiseizure efficacy of CBD with Δ9-THC (vs CBD alone) in patients with epilepsy. While natural selection may have led to combinations of phytochemicals in cannabis to resist infection or predation, there is no reason to expect “nature” to combine chemicals in a single plant to treat human epilepsy.

Animal Models of Seizures and Epilepsy

Animal models provide powerful assays to assess the potential antiseizure or antiepileptic effects of cannabinoids. Each preclinical paradigm has unique advantages and disadvantages, and many represent unique seizure etiologies, semiologies, or corresponding electroencephalography (EEG) patterns. Table 1 (adapted from [143–145]) summarizes animal models discussed in this review, grouped by relevance to human epilepsies. Acute models (e.g., kainic acid and pentylenetetrazol) allow high-throughput screening for upregulation of biomarkers, but cannot recapitulate spontaneous recurrent seizures or reduced seizure thresholds found in chronic epilepsy. Chronic models of seizure activity elicit spontaneous, recurrent seizures that can be recorded on video EEG. While technically challenging, these models better represent epileptogenesis and drug screening for humans. However chronic models are specific to the type of insult (traumatic brain injury, mouse genetic models), and may not reflect broad anatomical or functional changes in generalized epilepsy [145].

Table 1.

| Type of seizure model | Method | Mechanism | Relevant human condition | Common use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | MES | Electrical stimulation | Generalized tonic–clonic seizure | Drug screening (used as a first-line screening method for AEDs) |

| Acute | PTZ | GABAAR antagonist, Ca2+ channels (?), Na+ channels (?) | Generalized seizure | Drug screening (used as a first-line screening method for AEDs), seizure mechanism |

| Acute | KA | Ionotropic glutamate receptor (e.g., AMPAR, kainate receptor agonist) | Focal (temporal lobe) seizure | Drug screening, mechanism of seizures/epileptogenesis and cognitive impairments |

| Acute | Flurothyl | GABAAR antagonist | Multiple acute seizures, childhood epilepsy | Development of cognitive impairments from early life seizures |

| Acute | Other chemoconvulsant (e.g., bicuculline, 3-MPA, picrotoxin, etc.) | Various | Generalized seizures (or focal, if applied locally) | Drug screening |

| Acute | Hypoxia/ischemia | Anoxic depolarization, impaired Na+/K+ ATPase, ↑ extracellular impairments K+/[glutamte]/[aspartate], ↑ intracellular Na+, Ca2+ | Hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy | Age-specific (e.g., neonatal) drug screening, mechanisms of seizures and cognitive impairments |

| Acute | Hyperthermia | Activation of temperature-sensitive ion channels, release of proinflammatory cytokines | Febrile seizures | Drug screening, long-term consequences of seizures |

| Chronic with high propensity for induced seizures | Lithium/pilocarpine-induced chemical kindling | AChR agonist | Focal (temporal lobe) seizures | Drug screening, mechanism of seizures/epileptogenesis and cognitive impairments |

| Chronic with high propensity for induced seizures | Electrical (e.g., 6Hz psychomotor, limbic) kindling | Electric stimulation | Focal (temporal lobe) seizures | Drug screening, mechanism of seizures/epileptogenesis and cognitive impairments |

| Chronic epilepsy (SRS) | Stroke, TBI | Disease-specific models | Focal epilepsy | Drug screening, mechanism of seizures/epileptogenesis and cognitive impairments |

| Chronic epilepsy (SRS) | SE | Chronic treatment with KA or pilocarpine | Prolonged seizures | Drug screening |

| Chronic epilepsy (SRS) | Genetic (e.g., GAERs, WAG/Ij mice, photosensitive baboons) | Various | Specific seizure models (e.g., absence seizures, genetic) | Drug screening |

SRS = spontaneously recurring seizures; MES = maximal electroshock; PTZ = pentylenetetrazole; KA = kainic acid; 3-MPA = 3-mercaptopropionic acid; TBI = traumatic brain injury; SE = status epilepticus; GAERs = genetic absence epilepsy rats from Strousberg; GABAAR = γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor; AMPAR = α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor; ATPase = adenosine triphosphatase; AChR = acetylcholine receptor; AEDs = antiepileptic drugs

Preclinical Evidence of Cannabinoids in Epilepsy

Multiple animal models demonstrate the efficacy of cannabinoids in preventing seizures and reducing mortality in epilepsy. Animal models highlight dynamic changes in the endocannabinoid system follow chronic seizures, with both acute and chronic homeostatic regulatory components.

The Endocannabinoid System

Endocannabinoid release prevents seizure-induced neurotoxicity. Kainic acid (KA) (30 mg/kg)-induced seizures increased levels of the anandamide in wild-type mice (20 min postinjection) [146], and pilocarpine (375 mg/kg)-induced seizures increased levels of 2-AG (15 min postseizure onset) [147]. Thus, epileptiform activity triggers a neuroprotective, on-demand release of endocannabinoids (or increase endocannabinoid levels in a downstream pathway unrelated to neuroprotection). Pretreatment with an anandamide reuptake inhibitor (UCM707; 3 mg/kg) reduced KA-induced seizure severity, but not in mice with conditional CB1R deletion in principal forebrain excitatory neurons [146]. Blockade of the endocannabinoid catabolic enzyme FAAH (with AM374; 8 mg/kg) increased levels of anandamide and protected against KA (10 mg/kg)-induced hippocampal seizures and subsequent impairments in balance and coordination [148]. Inhibition of both FAAH (with AM374) and the anandamide reuptake transporter (with AM404) in rat hippocampus prevented α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid-induced excitotoxic insults (cytoskeletal damage and synaptic decline) in vitro and behavioral and memory impairment in vivo [149]. Blockage of FAAH and DAGLα (with AM6701, 5 mg/kg) raised levels of anandamide and 2-AG, protected against KA (10 mg/kg)-induced seizures, and reduced seizure-induced cytotoxicity [150]. The endocannabinoids, methanandamide, and 2-AG reduced neuronal firing in a low Mg2+in vitro model of status epilepticus, in a dose-dependent manner (EC50 145 ± 4.15 nM methanandamide, 1.68 ± 0.19 μM 2-AG) [151].

CB1Rs

Animal models demonstrate that activation of CB1Rs reduces seizure severity. Mice with conditional deletion of CB1Rs in principal forebrain excitatory neurons (but not interneurons) exhibited more severe KA-induced seizures (30 mg/kg) than wild-type controls. Conditional deletion of the CB1R increased gliosis and apoptosis following KA-induced seizures and prevented activation of the protective immediate early genes (c-Fos, Zif268, brain-derived neurotrophic factor) [146]. CB1R expression in hippocampal glutamatergic (but not GABAergic) inputs is necessary and sufficient to protect against KA-induced seizures [152]. Further, viral-induced overexpression of CB1Rs targeted to the hippocampus reduced KA-induced seizure severity, seizure-induced CA3 pyramidal cell death, and mortality [153], Together, these results demonstrate that CB1Rs could limit seizure activity and protect neurons from subsequent cell death and reactive gliosis.

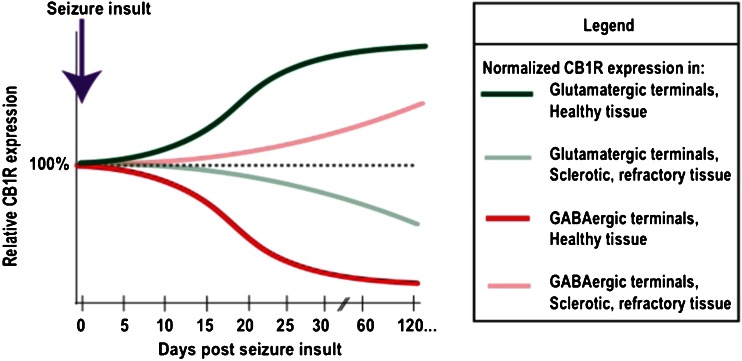

Seizures trigger homeostatic changes in hippocampal CB1Rs and the endocannabinoid system (reviewed in [154]) (Fig. 3). Levels of CB1R expression in the CA1-3 stratum oriens and radiatum (presumed excitatory inputs) and dentate gyrus steadily increased 1-week post-pilocarpine-induced seizures (Fig. 3, dark green trace) [147, 155–158]. However, sclerotic and nonsclerotic hippocampal tissue resected from patients with epilepsy displayed a reduction in DAGLα (2-AG biosynthetic enzyme), CB1R mRNA, and CB1R excitatory terminal immunoreactivity (Fig. 3, light green trace) [159]. Furthermore, compared with healthy controls, patients with temporal lobe epilepsy have reduced levels of anandamide in cerebrospinal fluid samples [160]. These findings suggest that seizure activity induces a homeostatic upregulation of excitatory terminal CB1Rs, which may reduce excitatory neurotransmitter release via DSE (see “The Endocannabinoid System”). This compensatory process may be impaired in patients with prolonged treatment-resistant epilepsy or hippocampal sclerosis, leading to neuronal hyperexcitability, pharmacoresistance, and inconsistent effects of cannabis exposure. However, further research is required to verify the functional effects of this potential process in human patients, and whether CB1R homeostasis indeed limits seizure severity or occurrence.

Fig. 3.

Homeostatic changes to hippocampal cannabinoid type 1 receptors (CB1Rs) in preclinical animal seizure models [147, 154–166]. GABA = γ-aminobutryic acid

In contrast to effects at excitatory terminals, seizures induce a homeostatic reduction in CB1R expression in inhibitory terminals (Fig. 3, dark red trace). Beginning 4 days following pilocarpine-induced seizures in rats, CB1R expression progressively decreased in hippocampal CCK+ inhibitory nerve terminals [161], particularly in the CA1 stratum pyramidale and the dentate gyrus inner molecular layer, unaccounted for by CA1 neuronal cell loss alone [155, 156, 162]. By reducing CB1R expression on inhibitory terminals (and presumed DSI), this homoeostatic process may limit network disinhibtion and restrain elevated excitability during prolonged epileptiform activity. In sclerotic hippocampal tissue removed from 1) 2 months post pilocarpine-induced seizures in mice [163], and 2) human patients [164], levels of CB1Rs remained consistently elevated in interneuron axonal terminals (Fig. 3, light red trace). This finding suggests that patients with prolonged, pharmacoresistant epilepsy may suffer from impaired CB1R homeostasis on inhibitory interneuron terminals, leading to prolonged disinhibition and network excitability. Postseizure changes in CB1Rs may be specific to seizure type or developmental stage, as mice with a single episode of febrile seizures induce an overall increase in DSI and CB1R on CCK+ interneurons [165, 166].

Modulators of the Endocannabinoid System and Synthetic CB1R Agonists/Antagonists

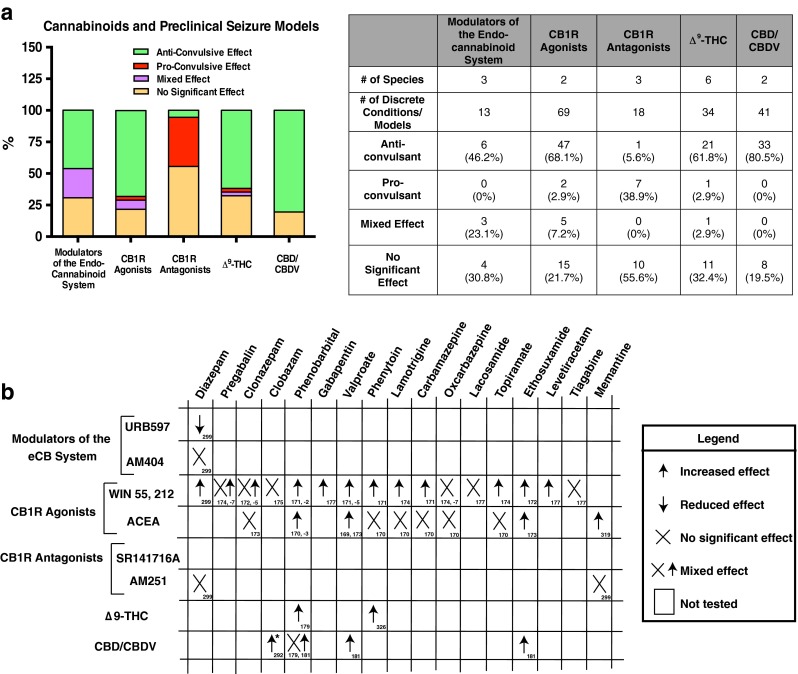

Figure 4 summarizes the effects of synthetic cannabinoids and phytocannabinoids in 175 pre-clinical seizure models or discrete conditions (adapted from [167]). These studies are subclassified by drug type and seizure model in corresponding tables in the Appendix (see Supplementary Material).

Fig. 4.

Summary of cannabinoids and preclinical seizure models. (A) Composite data from 175 preclinical seizure models (e.g., maximal electroshock, kainic acid) or discrete experimental designs (e.g., with combined antiseizure medications). Pro-/antiseizure effects are subclassified by given intervention: 1) modulators of the endocannabinoid (eCB) system (e.g., fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor URB597); 2) cannabinoid type 1 receptor (CB1R) agonists (e.g., WIN55212-2); 3) CB1R antagonists (e.g., SR141716A); 4) Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC); and 5) cannabidiol (CBD)/cannabidivarin (CBDV). (See Supplementary Material for complete description of preclinical studies.) (B) Summary of preclinical data on cannabinoid interactions with antiseizure medications. Sources indicated in boxes. *Recent evidence from a phase I clinical trial suggests that CBD/CBDV elevates serum concentrations of clobazam and N-desmethylclobazam in human pediatric patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy [292]. ACEA = arachidonyl-2'-chloroethylamide

Results from 13 studies from 3 species (rat, mouse, guinea pig) demonstrate that modulation of the endocannabinoid system (via inhibition of FAAH or anandamide reuptake) provides about 46.2 % (6/13) anticonvulsant, 23.1 % (3/13) mixed effect, and 30.8 % (4/13) no significant effect in seizure models. CB1R agonists produced an anticonvulsant effect in 68.1 % (47/69), proconvulsant effect in 2.9 % (2/69), mixed effect in 7.2 % (5/69), and no significant effect in 21.7 % (15/69) of seizure models in rats and mice. One study suggests that CB1R agonists may produce an anticonvulsant effect through CB1Rs at low doses, but a proconvulsive effect through TRPV1 channels at high doses [168]. In addition, CB1R agonists (WIN55, 212, ACEA) often produce a additive effect when combined with several commonly prescribed AEDs (see Fig. 4B) [169–177]. In 18 studies from mice, rats, and guinea pigs, CB1R antagonists were pro convulsant in 38.9 % (7/18), anti-convulsant in 5.6 % (1/18), and showed no significant effect in 55.6 % (10/18) of trials. Although CB1R agonists were anticonvulsant in 68.1 % of the studies, only 38.9 % of CB1R antagonists were proconvulsive (most showed no effect). Thus, while activation of the endocannabinoid system may prevent long-term consequences of seizure sequelae, inhibition of the endogenous protective mechanisms may not contribute significantly to seizures. Variations in the pro- vs anticonvulsant effects in each system may reflect specific effects of the species, seizure models (acute vs chronic, focal vs generalized), dose ranges, timing, or experimental design.

Phytocannabinoids: Δ9-THC and CBD

Evidence from 34 studies from 6 animal species demonstrate that Δ9-THC is anticonvulsant in 61.8 % (21/34), proconvulsant in 2.9 % (1/34), mixed in 2.9 % (1/34), and shows no significant effect in 32.4 % (11/34) of seizure models. Δ9-THC potentiated the effects of phenytoin and phenobarbital in the maximal electroshock model of generalized seizures [178, 179]. The National Toxicology Program noted a pro convulsant effect of Δ9-THC in rats and mice [180], although species-specific differences in CB1R expression may underlie variable responses to Δ9-THC. CBD and its homologue cannabidivarin (CBDV) were 80.5 % (33/41) anticonvulsive and 19.5 % (8/41) ineffective, at reducing seizures in mice and rats. Notably, no studies showed a proconvulsive effect for CBD or CBDV. CBDV potentiated the effects of phenobarbital, ethosuximide, and valproate in 2 seizure models [181]. These studies suggest that both Δ9-THC and CBD provide significant protection from seizures in preclinical animal trials, presenting potential targets for human studies.

Tolerance and Withdrawal

Prolonged treatment with Δ9-THC or synthetic CB1 agonists leads to a dose-dependent and region-specific desensitization, downregulation, and internalization of CB1Rs [182–203]. These changes produce tolerance to the acute behavioral effects of Δ9-THC in in vivo models, reducing cannabinoid-induced hypomotility, hypothermia, antinocioception, and memory impairment with repeated usage [182, 183, 185, 197, 199, 204, 205]. In several seizure models, prolonged Δ9-THC (but not CBD) exposure leads to tolerance to the antiepileptic activity of cannabinoids [206–210]. In humans, chronic cannabinoid usage produces tolerance towards Δ9-THC-mediated changes in autonomic behaviors, sleep and sleep EEGs, and self-reported psychotropic high, although these changes vary in frequent users [211–216].

Withdrawal from rats chronically dosed with Δ9-THC triggers rebound seizures and elevated anxiety-like responses in several preclinical animal studies [217–219]. Monkeys that previously self-administered intravenous Δ9-THC demonstrate abstinent symptoms of aggressiveness, hyperirritability, and anorexia [220], as well as impaired operant behavior [221]. Results from human studies demonstrated symptoms of anxiety, aggression, dysphoria, irritability, anorexia, sleep disturbances, and sweating during abstinence from chronic Δ9-THC usage, rescued by Δ9-THC re-administration [222]. Withdrawal from cannabis use can trigger rebound seizures in several preclinical animal and human studies [203, 209, 210, 223–226], although other studies show no proconvulsant effect of cannabis withdrawal [178, 227].

Unlike Δ9-THC, CBD (or nabiximols, CBD/Δ9-THC in a 1:1 ratio) does not seem to produce significant intoxication [228], tolerance [229–231], or withdrawal effects [232]. CBD and/or nabiximols may counteract the Δ9-THC-dominant effects of cannabis withdrawal [233–235]. In summary, evidence suggests that while both tolerance and some withdrawal symptoms may occur with Δ9-THC, CBD may limit the effects of cannabis tolerance and withdrawal, but more studies are needed.

Clinical Evidence of Cannabinoids in Epilepsy

Several clinical studies have examined the association between cannabis use and seizures. These include case studies, surveys and epidemiological studies, and clinical trials.

Case Studies

Case reports describe proconvulsant and anticonvulsant effect of cannabis, with the majority reporting either beneficial or lack of effect on seizure control. Selected examples illustrate the diverse spectrum of reported responses. Cannabis used 7 times within 3 weeks was associated with multiple tonic–clonic seizures in a patient previously seizure free for 6 months on phenytoin and phenobarbital. However, seizures were not temporally correlated with immediate intoxication or withdrawal [236]. Cannabis withdrawal increased complex partial seizure frequency in a 29-year-old man with a history of alcoholism and bipolar disorder (each of with are independently associated with seizures) [226]. In another 2-part case study, a 43-year-old on carbamazepine experienced about 5–6 nightly violent seizures lasting 1 min each. When he consumed about 40 mg C. sativa at night, seizure frequency was reduced by 70 %, but withdrawal triggered a doubling of his baseline seizure frequency. In the same study, a 60-year-old man with a 40-year history of cannabis usage (6–8 cigarettes per day) developed status epilepticus after cannabis withdrawal [225]. Additionally, synthetic “designer” cannabinoid drugs (“spice” or “K2”) induce new-onset seizures, tacharrythmia, and psychosis, often with greater severity and toxicity than cannabis [237–245]. The toxicity of these synthetic agents may result from their properties as full agonists of CB1R, while Δ9-THC is a partial agonist.

The majority of other studies demonstrate an anticonvulsant effect of cannabis. In a 1949 trial, administration of a Δ9-THC homolog (1,2-dimethyl heptyl) reduced the “severe anticonvulsant resistant (phenobarbital or phenytoin) grand mal epilepsy” in 2/5 children [246]. One patient whose seizures were not controlled on low-dose phenobarbital or phenytoin had fewer tonic–clonic seizures while smoking 2–5 cannabis cigarettes per day [247]. Myoclonic and other seizures were reportedly reduced in 3 adolescents on oral 0.07– 0.14 mg/kg Δ9-THC daily. Parents reported that their children were “more relaxed…more alert, more interested in her surroundings” [248]. In another study, a 45-year-old man with cerebral palsy and treatment-resistant focal epilepsy experienced a marked reduction in focal and secondary generalized seizures on daily marijuana [249]. Other recent cases also support the observation that cannabis use can reduce seizures in some patients [250, 251]. These studies suggest that cannabis can not only reduce seizure susceptibility, but also trigger rebound seizures during withdrawal. Limitations of open-label, often retrospective single case reports are compounded by the variability in epilepsy syndrome, differences in cannabis dosage, route, and composition.

Epidemiological Reports and Surveys

Recent epidemiological reports and surveys depict the incidence of medical marijuana usage for seizure control. The predicted prevalence of medical cannabis use in epileptic patients ranges from about 4 % (77 = total patient population in US medical cannabis program) to about 20 % (310 = total patients at a tertiary epilepsy clinic in Germany) [252, 253]. One percent of the medical marijuana users in California (~2500 = total patient population) use cannabis to control seizures [254]. In a telephone survey of 136 patients with epilepsy, 21.0 % were active users, 13.0 % were frequent users, 8.1 % were heavy users, and 3.0 % met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV criteria for marijuana dependence.

The majority of patient and caregiver surveys found either beneficial effects or no significant effect of cannabis in patients with epilepsy. In a small, 1976 survey of 300 patients with epilepsy, cannabis usage had no effect on seizure frequency in 30 % of patients, increased seizures in 1 patient, and decreased seizures in another [255]. A 1989 12-year retrospective study reported 10 % of 47 patients with “recreational drug-induced [tonic–clonic] seizures” had consumed cannabis prior to seizures, although this was confounded by recent cocaine, amphetamine, or LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) usage. No seizures were reported following cannabis use alone [256]. A single epidemiological study provided limited evidence that cannabis may possess antiseizure properties in humans. In a study of illicit drug use and new-onset seizures in Harlem utilizing a case–control methodology, cannabis used within 90 days before hospitalization was associated with a 2.8-fold decreased risk of first seizures among men but not women [257]. In a telephone survey of adult patients from a tertiary care epilepsy center, most active users reported beneficial effects on seizures (68 % reduced severity, 54 % reduced incidence), and 24 % of all subjects believed marijuana was an effective therapy for epilepsy. No patient reported a worsening of seizures with cannabis use [258]. The majority (84 %) of patients in a German tertiary care center reported that cannabis had no effect on their seizure control [253].

A 2013 survey of 19 parents of children with treatment-resistant epilepsy investigated the use of high CBD:Δ9-THC ratio artisanal marijuana products. These parents were primarily identified from social media and included 12 children with Dravet syndrome (DS). Of the 12 children with DS, parents reported that 5 (42 %) experienced a > 80 % reduction in seizure frequency and 2 (11 %) reported complete seizure freedom. The single child with Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (LGS) was reported to have a > 80 % reduction in seizure frequency. In addition to seizure control, parents reported positive effects of increased alertness (74 %), better mood (79 %), improved sleep (68 %), and decreased self-stimulation (32 %), and rare AEs of drowsiness (37 %) and fatigue (16 %) [259]. A more recent retrospective case study described 75 patients from Colorado with treatment-resistant epilepsy who moved to Colorado for oral cannabis extract treatment. Oral cannabis extract treatment controlled seizures in 57 % of patients, reduced seizures by >50 % in 33 % of patients, and showed greater effectiveness in patients with LGS (88.9 %) than in patients with DS (23.0 %). Reported additional benefits included improved behavior/alertness (33 %), language (10 %), and motor skills (10 %), as well as rare AEs of increased seizures (13 %) and somnolence/fatigue (12 %). Interestingly, the study also reported a significant, independent “placebo effect” of families moving to Colorado for treatment (see “Placebo Effect”) [260]. Collectively, these surveys suggest a predominantly antiseizure (or no significant) effect of cannabis usage. However, it is essential to consider the limitations of subjective self-reporting, potentially biased sampling of patient advocacy groups (over-reporting positive effects), and uncontrolled differences in CBD:Δ9-THC content in various strains of cannabis in these studies.

Clinical Trials

A recent Cochrane review assessed 4 primary clinical trials to examine the efficacy of medical marijuana in seizure control (summarized in Table 2, adapted from [11], [13]). Two of these studies demonstrated a partial antiseizure effect of CBD [261, 262], while 2 showed no significant effect [263, 264]. However, all 4 studies included significant limitations, including low study sizes, insufficient blinding or randomization, or incomplete data sets. The authors of the Cochrane review and a recent meta-analysis from the American Academy of Neurology both emphasized the need for follow-up placebo-controlled, blinded, randomized clinical trials examining the role of CBD in seizure control [12, 13].

Table 2.

| Study | Seizure type | Population size | Treatment (subjects per group) | Continued AEDs? | Duration | Outcome | Toxicity | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechoulam and Carlini [261] | Treatment-resistant, temporal lobe epilespy | 9 | CBD, 200 mg/day (4)Placebo (5) | NS | 3 months | CBD: seizure free (2), partial improvement (1), no change (1); placebo: no change (4) | None | No baseline seizure frequency; no definition of improvement; unclear if AEDs were changed; not truly randomized or blinded; unknown if groups were matched |

| Cunha et al. [262] | Treatment-resistant, temporal lobe epilespy | 15* | CBD 200–300 mg/day (8*) Placebo (8*) | Yes | 3–18 weeks | CBD: near seizure freedom (4), partial improvement (3), no change (1); placebo: no change (7), partial improvement (1) | Somnolence | Not clearly blinded (1 patient transferred groups); doses were adjusted in CBD group, not in placebo; CBD group received longer average treatment |

| Ames and Cridland [263] | Treatment-resistant epilepsy, intellectual/developmental disability | 12 | CBD 300 mg/day for 1 week; 200 mg/day for 3 weeks (6?) Placebo (6?) | NS | 4 weeks | No difference between CBD and placebo | Somnolence | Brief letter to the editor, details lacking on specifics; discontinued owing to “technical difficulties in preparing the drug” |

| Trembly and Sherman [264] | Treatment-resistant epilepsy | 10–12† | CBD 100 mg once daily Placebo |

Yes | 3 months baseline, 6 months CBD or placebo, then 6 months crossover to alternative treatment | No difference between CBD and placebo (seizure frequency or cognitive/behavioral tests) | None | Differences in sample size reporting; dada reported are incomplete (conference abstract)‡ |

AEDs = antiepileptic drugs; NS = not stated

*1 patient switched groups after 1 month

†Abstract and subsequent book chapters have different numbers

‡Only truly double-blind study

Phase I Clinical Trial for CBD in Treatment-resistant Epilepsy

Preliminary preclinical and clinical evidence reveal the therapeutic potential of CBD to reduce seizures with high tolerability and low toxicity. Accordingly, CBD represents a highly desirable treatment alternative for patients with early-onset, severe epilepsy such as DS and LGS. In addition to pharmacoresistant seizures, these patients suffer from severe neurodevelopmental delay, intellectual disability, autism, motor impairments, and significant morbidity and mortality [265, 266]. As patients with DS and LGS require effective and better-tolerated therapies and represent relatively homogeneous populations, they stand out as candidates for an initial trial of CBD safety and efficacy.

Study Design and Results

Investigator-initiated open-label studies at 10 epilepsy centers using Epidiolex (GWPharma, Salisbury, UK; 99 % CBD) collected data on 213 patients with treatment-resistant epilepsies. This predominantly pediatric population had a mean age of 10.8 years (range 2.0–26.0 years). CBD was added to existing AEDs; there was an average of 3 concomitant AEDs. The average baseline was 60 per month for total seizures and 30 per month for convulsive seizures.

The primary goal of the study was to assess safety but seizure diaries were obtained for convulsive, drop, and total seizures to provide a potential signal regarding efficacy. Twelve-week or longer continuous exposure data were obtained for 137 patients and were used in efficacy measures. The most common epilepsy etiologies were DS and LGS syndromes; others included Aicardi syndrome, Doose syndrome, tuberous sclerosis complex, CDKL5, Dup15q syndrome, and many others. At week 12, total convulsive and nonconvulsive seizures showed a median percent reduction from baseline of 54 %, and total convulsive seizures showed a median percent reduction from baseline of 51 %. In patients with DS (n = 23), CBD reduced convulsive seizure frequency by 53 %, and 16 % of DS reached complete convulsive seizure freedom by week 12. Atonic seizure frequency among patients with LGS (n = 10) was reduced by a median of 52 % at week 12. AEs > 10 % included somnolence (21 %), diarrhea (17 %), fatigue (17 %), and decreased appetite (16 %). Nine patients (4 %) were discontinued for AEs. The investigators concluded that CBD reduced seizure frequency across multiple drug-resistant epilepsy syndromes and seizure types and was generally well-tolerated in the open-label study. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are now ongoing for DS and LGS.

Safety Issues

There is a strong tendency to equate “cannabis as a natural therapy” with “cannabis as a safe therapy”. This a priori assumption—the naturalistic fallacy—is countered by many instances of toxic or deadly plants (e.g., amotoxins in mushrooms) and animals (e.g., tetrodotoxin in puffer fish). A more muted naturalistic view is that if side effects occur with cannabis, they would be less severe than those from drugs produced by the pharmaceutical industry. A recent Epilepsia survey of 776 individuals found that 98 % of the general public supported the use of medical marijuana for severe cases of epilepsy, compared with only 48 % of epileptologists. Similarly, the majority of the public and a minority of epileptologists thought that there was sufficient safety (96 % vs 34 %) and efficacy (95 % vs 28 %) data for medical marijuana use in severe epilepsy. This significant disparity in opinion between professionals and the lay public, possibly swayed by the appeal of natural remedies, emphasizes an increased need for further research and public education regarding medicinal cannabis and epilepsy [267].

As with efficacy, the most valid assessment of side effects is with RCTs. RCT data on the safety of Δ9-THC and CBD in adults comes from trials of cannabinoid-containing medications, including nabixomols [Sativex (GWPharma) 1:1 Δ9-THC:CBD], purified cannabis extracts [Cannador, Institute for Clinical Research, IKF, Berlin, Germany, (2:1 Δ9-THC:CBD)], synthetic Δ9-THC analogues Dronabinol and Nabilone. These drugs have been approved by many international regulatory agencies. In a meta-analysis of 1619 patients treated with nabiximols for neurological indications (mainly pain, spasticity, spasm, or tremor) for 6 months or less, 6.9 % of those on cannabinoid therapies were discontinued because of adverse effects versus 2.25 % in the placebo groups [12]. Adverse effects occurring in at least 2 studies included nausea, dizziness, increased weakness, behavioral or mood changes, hallucinations, suicidal ideation, fatigue, and feeling of intoxication. No deaths from overdose were reported [12]. However, our knowledge on the safety of these compounds in children is very limited.

The adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use were recently reviewed [268]. Δ9-THC is presumed to be the major cannabinoid resulting in adverse acute and chronic health effects of cannabis. The 4-fold increase in Δ9-THC content of confiscated cannabis in the last 20 years is associated with increased acute complications. In 2011, there were 129,000 emergency department visits for cannabis alone and 327,000 additional visits for cannabis in combination with other drugs. From 2004 to 2011, the rate of emergency department visits for cannabis toxicity doubled [268]. Short-term use can impair short-term memory, coordination, and judgment. In high doses, paranoia and psychosis can occur [137, 269]. Long-term use of recreational cannabis in adolescents is associated with addiction (9 % overall but 17 % among adolescents) and impaired cognitive and academic performance [270–274]. Additionally, cannabis treatment in animal and human studies altered brain development (especially with use in early childhood) and structure [272, 275–277], creating long-lasting functional and structural brain abnormalities [277–279]. Early and/or heavy cannabis use is associated with neurochemical abnormalities on magnetic resonance spectroscopy [272], impaired maintenance of neuronal cytoskeleton dynamics [277], decreased white matter development or integrity [272, 275, 276], increased impulsivity [276], and abnormal activation patterns during cognitive tasks on functional magnetic resonance imaging [272, 280]. In patients with multiple sclerosis, use of cannabis is associated with impaired cognition and activation patterns on functional magnetic resonance imaging [281]. Further research is required to determine the short- and long-term effects of CBD alone, which may have lower toxicity than whole plant cannabis or Δ9-THC.

Cannabidiol Formulations, Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Drug–Drug Interactions

We are aware of 3 pharmaceutical products that are currently in trials or in development: 1) Epidiolex (99 % CBD derived from C. sativa plants, in a strawberry-flavored sesame oil), 2) synthetic CBD from Insys Therapeutics (Chandler, AZ, USA), and 3) Transdermal CBD gel from Zynerba Pharmaceuticals (Devon, PA, USA). Other CBD-containing products are available commercially and obtained online [e.g., Realm of Caring's Charlotte's Web (whole cannabis extract containing 50 mg/ml CBD)]. However, the quality control and consistency of these products may vary considerably. Indeed, a recent study by the US Food and Drug Administration tested 18 products, claimed to contain CBD, made by 6 companies. Of these, 8 contained no CBD, 9 contained <1 % CBD, and 1 contained 2.6 % CBD (http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/PublicHealthFocus/ucm435591.htm).

Because lipophilic cannabinoids (including CBD) have low water solubility, CBD is traditionally delivered orally in either an oil-based capsule or sublingual spray, permitting less variable pharmacokinetics in gastrointestinal absorption. A single 10-mg dose of nabiximols (equal parts CBD and Δ9-THC) in humans produces a maximum serum concentration (Cmax) of 3.0 ± 3.1 μg/l (buccal) [2.5 ± 1.8 μg/l (sublingual)] and maximum time (Tmax) of 2.8 ± 1.3 h (buccal) [1.6 ± 0.7 h (sublingual)] [282]. CBD is primarily protein-bound in the blood, and preferentially deposits in brain and adipose tissue [283].

The cannabinoids are primarily metabolized by the liver cytochrome P-450 (CYP-450) enzymes. Both Δ9-THC and CBD can inhibit CYP-450 metabolic activity, particularly the CYP2C isozymes at low concentrations and CYP3A4 isozymes at higher concentrations [284–289]. CYP2C and CYP3A4 are induced by carbamazepine, topiramate, and phenytoin, and inhibited valproate and other drugs [290]. The cannabinoids, particularly CBD, can inhibit other isozymes, including 2D6 and 1A1 [285, 291]. Therefore, use of Δ9-THC or CBD could potentially contribute to bidirectional drug–drug interactions with antiepileptic and other drugs. In our open-label CBD study, patients treated with CBD had elevated levels of the nordesmethyl metabolite of clobazam [292], which may account for a portion of the apparent sedation, as well as efficacy, of CBD.

Placebo Effect

The magnitude of the placebo response is related to the power of belief. Given the social and mainstream media attention selectively reporting dramatic benefits of artisanal cannabis preparations for children with epilepsy, there are high expectations on the part of many parents. The potent role of the placebo response was suggested by a recent survey of parents whose children with epilepsy who were cared for at Colorado Children’s Hospital. A beneficial response (>50 % seizure reduction) was reported 3 times more often by parents who moved to the state compared with those who were long-time residents [260]. No differences in epilepsy syndrome, type of artisanal preparation, or other factor could account for this difference.

While studies have reported a significant placebo response in adult patients (such as those with Parkinson’s Disease [293]), placebo response rates are particularly high among children and adolescents in a subset of disorders, including psychiatric (anxiety, major depression, and obsessive compulsive and attention deficit disorders), medical (asthma), and painful (migraine, gastrointestinal) conditions [294, 295]. As the current RCTs of CBD primarily target children with severe epilepsy, this may be an important issue. Among patients with treatment-resistant focal epilepsy, a meta-analysis found that the placebo response in children (19.9 %) was significantly higher than in adults (9.9 %), while the response to the AED was not statistically different in children (37.2 %) and adults (30.4 %) [296]. In one predominantly pediatric LGS trial, seizures were reduced in 63 % of placebo-treated patients and 75 % of drug-treated patients [297]. Paradoxically, the intense interest and strong beliefs in the efficacy of cannabis for epilepsy may elevate placebo responses and make it more difficult to demonstrate a true benefit in RCTs.

Legal/Ethical Concerns

The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) classifies cannabis and products derived from cannabis plants as Schedule I drugs. Schedule I drugs have a high potential for abuse and no currently accepted medical use; they are the most dangerous drugs of all the drug schedules with potentially severe psychological or physical dependence (DEA website; http://www.dea.gov/druginfo/ds.shtml). It is thus paradoxical that opiates and benzodiazepines, which have a much greater potential for psychological and physical dependence than cannabis, are classified as Schedule II drugs. With regard to the DEA’s “claim” that cannabis-derived drugs have no currently accepted medical use, therapies such as nabiximols (CBD and Δ9-THC) and other products have been approved by regulatory agencies in >20 countries. These approvals are based on RCTs that establish efficacy and a favorable safety profile, including a low potential for abuse [228, 298].

The Schedule I categorization makes it challenging for investigators to study cannabis-derived cannabinoids in basic and clinical science. There is often a long and costly process to secure approvals and inspections to obtain cannabinoids, purchase a large safe, the weight of which may require clearance from engineers, and add security systems to the room and building in which they are stored. The Schedule I designation often prevents patients who live in developmental centers or residential homes from participating in clinical trials. The threshold of effort for basic and clinical investigators to study cannabinoids remains as high as ever, while the availability of these substances for parents to give is expanding rapidly. This has created a widening gap between knowledge and exposure, an especially relevant concern in children for whom safety data are largely lacking.

Conclusion

For over a millennium, pre-clinical and clinical evidence have shown that cannabinoids such as CBD can be used to reduce seizures effectively, particularly in patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy. However, many questions still remain (see Box 1) regarding the mechanism, safety, and efficacy of cannabinoids in short- and long-term use. Future basic science research and planned multicenter, placebo-controlled clinical trials will provide insight into cannabinoid function and the potential neuroprotective effects of the endocannabinoid system. These findings will increase our mechanistic understanding of seizures and may provide novel, targeted therapeutics for epilepsy.

| Box 1 Unanswered questions and directions for future studies |

| 1. How do the pro and anti-epileptic effects of cannabis change with development? Are there age-specific differences in responsiveness, side effects, and target receptor expression? 2. What are the long-term effects of cannabis/cannabidiol use? 3. Are certain types of seizures or genetic channelopathies more likely to respond to cannabidiol than others? 4. What is the safety of cannabidiol in patients with special conditions (pregnancy, recent or planned surgery, vagus nerve stimulation, etc.)? 5. How do synthetic cannabinoids (“spice” or “K2”) dysregulate the central nervous system to induce seizures? What is their relative safety and toxicity relative to cannabis? |

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOCX 1.71 mb)

Acknowledgments

Drs. Orrin Devinsky and Ben Whalley have received research support from GW Pharmaceuticals. We acknowledge FACES (Finding a Cure for Epilepsy and Seizures) for generous help in the preparation of this manuscript. R.W.T. is supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (5R37MH071739) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (5R01NS074785, 5R01NS024067).

References

- 1.Fisher RS, et al. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE) Epilepsia. 2005;46:470–472. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.66104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:314–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Refractory epilepsy: a progressive, intractable but preventable condition? Seizure. 2002;11:77–84. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2002.0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwan P, Schachter SC, Brodie MJ. Drug-resistant epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:919–926. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1004418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nilsson L, et al. Risk factors for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: a case–control study. Lancet. 1999;353:888–893. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walczak TS, et al. Incidence and risk factors in sudden unexpected death in epilepsy: a prospective cohort study. Neurology. 2001;56:519–525. doi: 10.1212/WNL.56.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devinsky O. Patients with refractory seizures. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1565–1570. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905203402008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacoby A, Baker GA. Quality-of-life trajectories in epilepsy: a review of the literature. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12:557–571. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogawski MA. The intrinsic severity hypothesis of pharmacoresistance to antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 2013;54(Suppl. 2):33–40. doi: 10.1111/epi.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perucca E. Is there a role for therapeutic drug monitoring of new anticonvulsants? Clin Pharmacokinet. 2000;38:191–204. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200038030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devinsky O, et al. Cannabidiol: pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Epilepsia. 2014;55:791–802. doi: 10.1111/epi.12631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koppel BS, et al. Systematic review: efficacy and safety of medical marijuana in selected neurologic disorders: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;82:1556–63. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gloss D, Vickrey B. Cannabinoids for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009270.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abel EL. Marihuana: the first twelve thousand years. New York: Plenum Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russo EB, et al. Phytochemical and genetic analyses of ancient cannabis from Central Asia. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:4171–4182. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lozano I. The therapeutic use of Cannabis sativa L. in Arabic medicine. J Cannabis Ther. 2001;1:63–70. doi: 10.1300/J175v01n01_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szaflarski JP, Bebin EM. Cannabis, cannabidiol, and epilepsy—from receptors to clinical response. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;41:277–282. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.08.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Shaughnessy WB. On the preparations of the Indian hemp, or Gunjah. Prov Med J Retrosp Med Sci. 1843;5:363–369. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds JR. Epilepsy: its symptoms, treatment, and relation to other chronic convulsive diseases. J. Churchill (Ed.) London, 1861. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Gowers W. Epilepsy and other chronic convulsive disorders. Churchill (Ed.) London, 1881.

- 21.Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R. Isolation, structure, and partial synthesis of an active constituent of hashish. J Am Chem Soc. 1964;86:1646–1647. doi: 10.1021/ja01062a046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R. The isolation and structure of delta-1-tetrahydrocannabinol and other neutral cannabinoids from hashish. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;9:217–224. doi: 10.1021/ja00730a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams R, Pease DC, Clark JH. Isolation of cannabinol, cannabidiol, and quebrachitrol from red oil of Minnesota wild hemp. J Am Chem Soc. 1940;62:2194–2196. doi: 10.1021/ja01865a080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michoulam R, Shvo Y, Hashish I. The structure of cannabidiol. Tetrahedron. 1963;19:2073–2078. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(63)85022-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuda LA, et al. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature. 1993;365:61–65. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Llano I, et al. Synaptic- and agonist-induced excitatory currents of Purkinje cells in rat cerebellar slices. J Physiol. 1991;434:183–213. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pitler TA, Alger BE. Postsynaptic spike firing reduces synaptic GABAA responses in hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4122–4132. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-04122.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreitzer AC, Regehr WG. Retrograde inhibition of presynaptic calcium influx by endogenous cannabinoids at excitatory synapses onto Purkinje cells. Neuron. 2001;29:717–727. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00246-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kreitzer AC, Regehr WG. Cerebellar depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition is mediated by endogenous cannabinoids. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC174. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-j0005.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson RI, Kunos G, Nicoll RA. Presynaptic specificity of endocannabinoid signaling in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2001;31:453–462. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devane WA, et al. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science. 1992;258:1946–1949. doi: 10.1126/science.1470919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mechoulam R, et al. Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00109-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugiura T, et al. 2-Arachidonoylglycerol: a possible endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand in brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;215:89–97. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alger BE. Retrograde signaling in the regulation of synaptic transmission: focus on endocannabinoids. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;68:247–286. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(02)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown SP, Brenowitz SD, Regehr WG. Brief presynaptic bursts evoke synapse-specific retrograde inhibition mediated by endogenous cannabinoids. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1048–1057. doi: 10.1038/nn1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maejima T, Ohno-Shosaku T, Kano M. Endogenous cannabinoid as a retrograde messenger from depolarized postsynaptic neurons to presynaptic terminals. Neurosci Res. 2001;40:205–210. doi: 10.1016/S0168-0102(01)00241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melis M, et al. Prefrontal cortex stimulation induces 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol-mediated suppression of excitation in dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10707–10715. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3502-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katona I, Freund TF. Endocannabinoid signaling as a synaptic circuit breaker in neurological disease. Nat Med. 2008;14:923–930. doi: 10.1038/nm.f.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Marzo V, et al. Formation and inactivation of endogenous cannabinoid anandamide in central neurons. Nature. 1994;372:686–691. doi: 10.1038/372686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Marzo V, Deutsch DG. Biochemistry of the endogenous ligands of cannabinoid receptors. Neurobiol Dis. 1998;5:386–404. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Di Marzo V, et al. Endocannabinoids: endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligands with neuromodulatory action. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:521–528. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(98)01283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugiura T, et al. Biosynthesis and degradation of anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol and their possible physiological significance. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2002;66:173–192. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stella N, Schweitzer P, Piomelli D. A second endogenous cannabinoid that modulates long-term potentiation. Nature. 1997;388:773–778. doi: 10.1038/42015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pertwee RG. Cannabinoid receptor ligands: clinical and neuropharmacological considerations, relevant to future drug discovery and development. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2000;9:1553–1571. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.7.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pi-Sunyer F, et al. Effect of rimonabant, a cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker, on weight and cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight or obese patients - RIO-North America: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:761–775. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.7.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cahill K, Ussher M. Cannabinoid type 1 receptor antagonists (rimonabant) for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007:CD005353. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Glass M, Felder CC. Concurrent stimulation of cannabinoid CB1 and dopamine D2 receptors augments cAMP accumulation in striatal neurons: evidence for a Gs linkage to the CB1 receptor. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5327–5333. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05327.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mackie K, Hille B. Cannabinoids inhibit N-type calcium channels in neuroblastoma-glioma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:3825–3829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Caulfield MP, Brown DA. Cannabinoid receptor agonists inhibit Ca current in NG108-15 neuroblastoma cells via a pertussis toxin-sensitive mechanism. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;106:231–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Twitchell W, Brown S, Mackie K. Cannabinoids inhibit N- and P/Q-type calcium channels in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:43–50. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szabo GG, et al. Presynaptic calcium channel inhibition underlies CB(1) cannabinoid receptor-mediated suppression of GABA release. J Neurosci. 2014;34:7958–7963. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0247-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deadwyler SA, et al. Cannabinoids modulate potassium current in cultured hippocampal neurons. Receptors Channels. 1993;1:121–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deadwyler SA, et al. Cannabinoids modulate voltage sensitive potassium A-current in hippocampal neurons via a cAMP-dependent process. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273:734–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hampson RE, et al. Role of cyclic AMP dependent protein kinase in cannabinoid receptor modulation of potassium "A-current" in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Life Sci. 1995;56:2081–2088. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mu J, et al. Protein kinase-dependent phosphorylation and cannabinoid receptor modulation of potassium A current (IA) in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Pflugers Arch. 2000;439:541–546. doi: 10.1007/s004249900231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Henry DJ, Chavkin C. Activation of inwardly rectifying potassium channels (GIRK1) by co-expressed rat brain cannabinoid receptors in Xenopus oocytes. Neurosci Lett. 1995;186:91–94. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mackie K, et al. Cannabinoids activate an inwardly rectifying potassium conductance and inhibit Q-type calcium currents in AtT20 cells transfected with rat brain cannabinoid receptor. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6552–6561. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06552.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McAllister SD, et al. Cannabinoid receptors can activate and inhibit G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels in a xenopus oocyte expression system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:618–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Photowala H, et al. G protein betagamma-subunits activated by serotonin mediate presynaptic inhibition by regulating vesicle fusion properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4281–4286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600509103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schlicker E, Kathmann M. Modulation of transmitter release via presynaptic cannabinoid receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:565–572. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01805-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chevaleyre V, Takahashi KA, Castillo PE. Endocannabinoid-mediated synaptic plasticity in the CNS. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:37–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Piomelli D. The molecular logic of endocannabinoid signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:873–884. doi: 10.1038/nrn1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Katona I, et al. Presynaptically located CB1 cannabinoid receptors regulate GABA release from axon terminals of specific hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:4544–4558. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04544.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marsicano G, Lutz B. Expression of the cannabinoid receptor CB1 in distinct neuronal subpopulations in the adult mouse forebrain. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4213–4225. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dudok B, et al. Cell-specific STORM super-resolution imaging reveals nanoscale organization of cannabinoid signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:75–86. doi: 10.1038/nn.3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kawamura Y, et al. The CB1 cannabinoid receptor is the major cannabinoid receptor at excitatory presynaptic sites in the hippocampus and cerebellum. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2991–3001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4872-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Katona I, et al. Molecular composition of the endocannabinoid system at glutamatergic synapses. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5628–5637. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0309-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lafourcade M, et al. Molecular components and functions of the endocannabinoid system in mouse prefrontal cortex. PLoS One. 2007;2 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wittmann G, et al. Distribution of type 1 cannabinoid receptor (CB1)-immunoreactive axons in the mouse hypothalamus. J Comp Neurol. 2007;503:270–279. doi: 10.1002/cne.21383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]