Abstract

The flagellate Trypanosoma brucei causes sleeping sickness in humans and nagana in animals. Only a few drugs are registered to treat trypanosomiasis, but those drugs show severe side effects. Also, because some pathogen strains have become resistant, new strategies are urgently needed to combat this parasitic disease. An underexplored possibility is the application of combinations of several trypanocidal agents, which may potentiate their trypanocidal activity in a synergistic fashion. In this study, the potential synergism of mutual combinations of bioactive alkaloids and alkaloids with a membrane-active steroidal saponin, digitonin, was explored with regard to their effect on T. b. brucei. Alkaloids were selected that affect different molecular targets: berberine and chelerythrine (intercalation of DNA), piperine (induction of apoptosis), vinblastine (inhibition of microtubule assembly), emetine (intercalation of DNA, inhibition of protein biosynthesis), homoharringtonine (inhibition of protein biosynthesis), and digitonin (membrane permeabilization and uptake facilitation of polar compounds). Most combinations resulted in an enhanced trypanocidal effect. The addition of digitonin significantly stimulated the activity of almost all alkaloids against trypanosomes. The strongest effect was measured in a combination of digitonin with vinblastine. The highest dose reduction indexes (DRI) were measured in the two-drug combination of digitonin or piperine with vinblastine, where the dose of vinblastine could be reduced 9.07-fold or 7.05-fold, respectively. The synergistic effects of mutual combinations of alkaloids and of alkaloids with digitonin present a new avenue to treat trypanosomiasis but one which needs to be corroborated in future animal experiments.

INTRODUCTION

Trypanosoma brucei is a single-celled protozoan that, if left untreated, can cause the deadly sleeping sickness (human African trypanosomiasis [HAT]). Two trypanosome subspecies affect people: T. b. gambiense (found in western and central Africa) and T. b. rhodesiense (in eastern and southern Africa). The disease caused by T. b. gambiense is more abundant and accounts for more than 98% of all infections of patients. Infected persons go through two stages of the disease. The first or hemolymphatic phase causes fever, itching, and headache. In the second or neurological stage, the blood-brain barrier is crossed by the parasite and the central nervous system is affected. This is the stage at which the disturbance of the sleep cycle appears (hence the name of the disease). The vector of T. brucei is the tsetse fly (genus Glossina), which can transmit the parasite to a diversity of mammalian hosts, including humans (1, 2).

Only four drugs are registered for treatment of the disease. Suramin and pentamidine are used for the first stage of the sleeping sicknesses caused by T. b. rhodesiense and T. b. gambiense, respectively. Melarsoprol is registered for treatment of the neurological stage. Eflornithine is a drug which is less toxic than melarsoprol but is effective only against T. b. gambiense (2). Suramin and pentamidine were first synthesized more than 70 years ago, and resistance to those two drugs seems to have been established (3). Since only a few drugs, all of which exhibit severe side effects, are registered for treatment of African trypanosomiasis and since resistance to those drugs is emerging, new therapeutic strategies are urgently required (4, 5).

New strategies include the development of new drugs such as novel diamidines with better pharmacokinetic properties or of new pentamidine-like prodrugs. New oral drugs, such as fexinidazole, benzoxaborole, and oxaboroles, are currently in clinical trials. An interesting alternative to treatment with a single drug is the application of a combination therapy using two or more drugs. Nifurtimox-eflornithine (NECT) combination therapy was developed for treatment of trypanosomiasis in 2009. It is being used for treatment of the second stage of sleeping sickness, and it is considered one of the safest therapies (6).

For millennia, medicinal plants and their secondary metabolites have played an important role in the treatment of different diseases and health disorders (7). During the last 30 years, more than 1,000 new drugs have been registered, 28% of which are products that come from nature or are derivatives of natural products. Secondary metabolites also represent an interesting alternative to synthetic antiparasitic drugs (1). Many medicinal plants and isolated natural products have already been screened, and some which show a high degree of trypanocidal activity have been discovered (8, 9, 10).

Complex extracts of medicinal plants are commonly used in phytomedicine. These extracts consist of several bioactive compounds from different classes which interact with a multitude of targets (and are thus multitarget agents) (11, 12). Both clinical studies and the experience gathered throughout history have shown that these mixtures have definite biological activity (12). Regarding the efficacy of natural products in phytotherapy, it seems that synergism of various compounds present in a plant extract is crucial.

When the measured effect of a combination of 2 or more compounds is greater than what would have been expected from the effects of individual compounds, synergy is present (13). Using two or more drugs in combination can lead to the maintenance or enhancement of the main therapeutic effect, by lowering the dosage and consequently the toxicity of medications. Combination therapies have already been used for many years against some of the most threatening diseases, such as cancer, hypertension, and AIDS, for the above-mentioned reasons (14).

Among plant secondary metabolites, alkaloids represent one extensive and prominent nitrogen-containing class of bioactive molecules (15). Wide structural diversity of alkaloids exists, and the estimated number of structures exceeds 21,000 (12). In contrast to many terpenoids and phenolics, alkaloids often act upon a particular and specific target in animals, especially one involved with the nervous system, such as receptors of neurotransmitters, ion channels, or enzymes which degrade neurotransmitters (16, 18). Among other drug classes, alkaloids have already been screened for anti-inflammatory, anti-Alzheimer, neuromodulatory, anticancer, antitrypanosomal, and antimicrobial activity (16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23).

In this study, six alkaloids which had previously been identified as trypanocidal in earlier studies in our laboratory (S. Krstin and M. Wink, submitted for publication) (23) and the steroidal saponin digitonin were tested in various combinations to explore whether such combinations can result in synergistic trypanocidal activity against bloodstream forms of T. b. brucei. Alkaloids affecting different targets and those affecting the same molecular targets were combined. Modes of action included intercalation of DNA, induction of apoptosis, inhibition of microtubule assembly, membrane permeabilization, and inhibition of protein biosynthesis. Some of the selected alkaloids, such as chelerythrine or berberine, have two or more targets in the cell. The steroidal saponin digitonin was chosen because it disturbs membrane fluidity and can facilitate the uptake of polar metabolites (24). Digitonin is an amphiphilic membrane-disrupting steroid that can interact with biomembranes containing cholesterol and lyse cells. It has already been shown that digitonin can enhance the antimalarial activity of the polar phenolic epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) in a synergistic fashion (25). This is the first report of studies demonstrating the efficacy of combinations of alkaloids and digitonin against T. b. brucei.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Emetine, berberine, suramin (≥95%), fetal bovine serum (FBS), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) (≥97.5%), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (≥99.9%), HEPES (≥95%), glucose (≥95%), pyruvate, hypoxanthine (98%), thymidine (99% to 100%), adenosine, digitonin, piperine (97%), bathocuproinedisulfonic acid disodium salt, and β-mercaptoethanol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich GmbH, Germany. Chelerythrine and homoharringtonine came from Baoji Herbest Bio-Tech Co., Ltd. (Baoji, Shaanxi, China), and minimal essential medium (MEM), nonessential amino acids (NEAA), penicillin, streptomycin, and l-glutamine from Gibco Invitrogen, Germany. Vinblastine was obtained from the pharmacy of the Heidelberg University Hospital (Heidelberg, Germany) as a ready-to-use injection solution (1 mg/ml).

Cell lines.

T. b. brucei was kindly supplied by Peter Overath (Max Planck Institut für Biologie, Tübingen, Germany) and has been cultured at the Institute of Pharmacy and Molecular Biotechnology (IPMB, Heidelberg, Germany) since 1999. T. b. brucei bloodstream forms were maintained in complete Baltz medium (26) and cultivated at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. All experiments were performed with cells in their logarithmic-growth phase. T. b. brucei was used, as this subspecies is nonpathogenic for humans, which facilitates its study under laboratory conditions.

MTT cytotoxicity assay.

Using the MTT cytotoxicity assay, the trypanocidal potential of combinations of alkaloids and digitonin was investigated (27). The MTT assay is a rapid, quantitative and versatile colorimetric assay and is based on the measurement of viability, indicated by the reduction of the proportion of the tetrazolium salt MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] to its purple formazan salt in the mitochondria of living cells. Dead cells cannot reduce the tetrazolium salt, and therefore a distinction between live and dead cells can be made.

Combinations of alkaloids and digitonin.

Stock solutions of drugs were prepared in water or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in concentrations that ranged from 0.1 to 50 mM. To determine whether combinations of alkaloids and digitonin result in a synergistic, additive, or antagonistic effect, a fixed nontoxic concentration (20% inhibitory concentration [IC20] or less) of alkaloids or digitonin was added to serial 2-fold dilutions of another alkaloid or digitonin. Serial dilutions were performed in the respective media, and the maximal concentration of DMSO did not exceed 1%. T. b. brucei cells (in a 96-well plate; Greiner Labortechnik) (2 × 104/well) were incubated with test compounds for 48 h under standard conditions. Afterward, 0.5 mg/ml of MTT was added. After 4 h of incubation, the formazan crystals produced by viable cells were dissolved in 100 μl of DMSO and the reaction mixture was shaken at room temperature for 10 min. Then, the absorbance of the wells was measured at 570 nm using a Biochrome Asys UVM340 microplate reader (Biochrom, United Kingdom). The trypanocidal drug suramin (IC50 = 0.13 μM) was used as a positive control.

Analysis of combination effects.

Analyzing data from combination studies is complicated and very critical matter. Therefore, in order to correctly estimate the nature of a combination, four different analytical methods were applied to the analysis of the combination effect.

First of all, the combination index (CI) was calculated. It represents a general expression of drug interactions in pharmacology, and determining CI values is a simple way to quantify either synergism or antagonism. It is calculated as follows:

| (1) |

where C (A, X) and C (B, X) represent the concentrations of drug A and drug B used in combination to produce mean effect X (IC50). IC (X, A) and IC (X, B) represent the median-effect (IC50) values for single drugs A and B. The combination index (CI) quantitatively describes synergism (CI < 1), additive effect (CI = 1), and antagonism (CI > 1) (28, 29).

Furthermore, dose reduction indexes (DRI) or reversal ratios (RR) or cytotoxicity enhancement ratios (CER) were used to determine if a combination could lead to a reduction of the alkaloid drug dose. Dose reduction is important, because it could lead to reduced toxicity and to maintained or increased main therapeutic efficacy. Favorable DRI values would be >1, whereas unfavorable ones would be <1, but values above 1 do not necessarily represent synergism, because additive effects, and even slight antagonism, can also lead to values of >1. DRI values are calculated as follows (14):

| (2) |

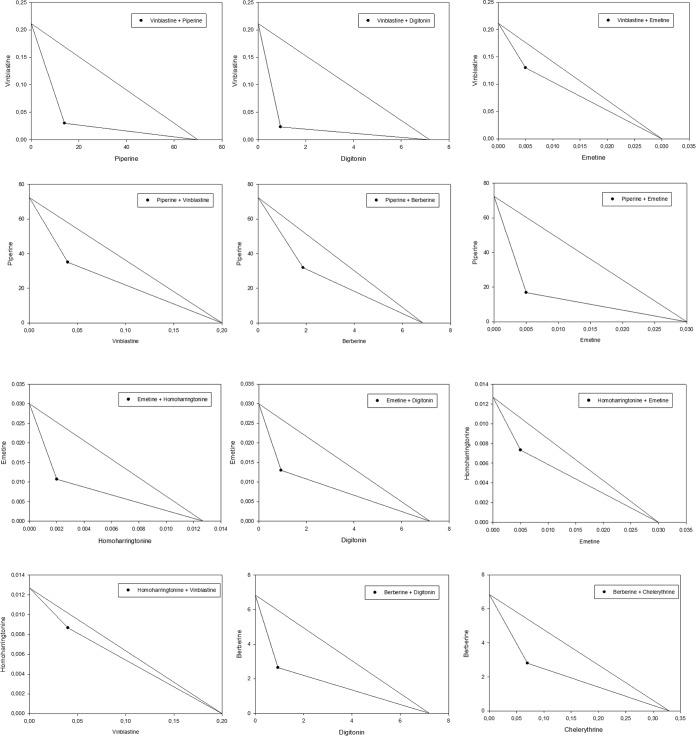

In addition, the nature of the interaction between compound A and compound B was analyzed using an isobologram. The IC50 concentrations of drugs A and B are plotted on the x and y axes in a two-coordinate plot, corresponding to (CA, 0) and (0, CB), respectively. The line connecting these two points is the line of additivity. The concentrations of the two drugs that had been used in a combination to provide the same effect, denoted as (CA, CB), are placed in the same plot. When CA and CB are located below the line, the result of the combination effect is synergy; if they are on the line, it is a sign of additivity; and if they are above the line, it is a sign of antagonism (29).

Finally, the median-effect equation was used. This equation is applicable to and can describe behavior in many biological systems, such as enzymatic, cellular, and whole-animal systems. The median-effect equation is as follows:

| (3) |

where D represents the dose, fa represents the fraction of the affected (killed) cells, and fu represents the fraction of the unaffected (viable) cells left after exposure to dose D of the drug. Dm represents the dose required to achieve the median effect (equivalent to the IC50), and m is a Hill-type coefficient signifying the sigmoidal property of the dose-effect curve. The median-effect equation can be linearized by taking the logarithms of both sides, and the median-effect plots were drawn by plotting log [(fa)−1 − 1]−1 against log D. The linearity of the median-effect plot (as determined from linear-regression-coefficient [R] values) determines the applicability of the present method (30).

Statistical analysis.

All experiments were carried out in triplicate and repeated at least three times unless otherwise stated. Using four-parameter logistic regression and SigmaPlot 11.0 software, a sigmoidal curve was fitted and the IC50, which represents a 50% reduction in viability compared to the results seen with nontreated cells, was calculated. The data are represented as means ± standard deviations (SD). Isobologram analysis results, the correlation coefficients (r) for the regression lines of median-effect plots, and the results of statistical tests were also determined by using SigmaPlot 11.0 software. A P value below 0.05 was considered to represent statistical significance.

RESULTS

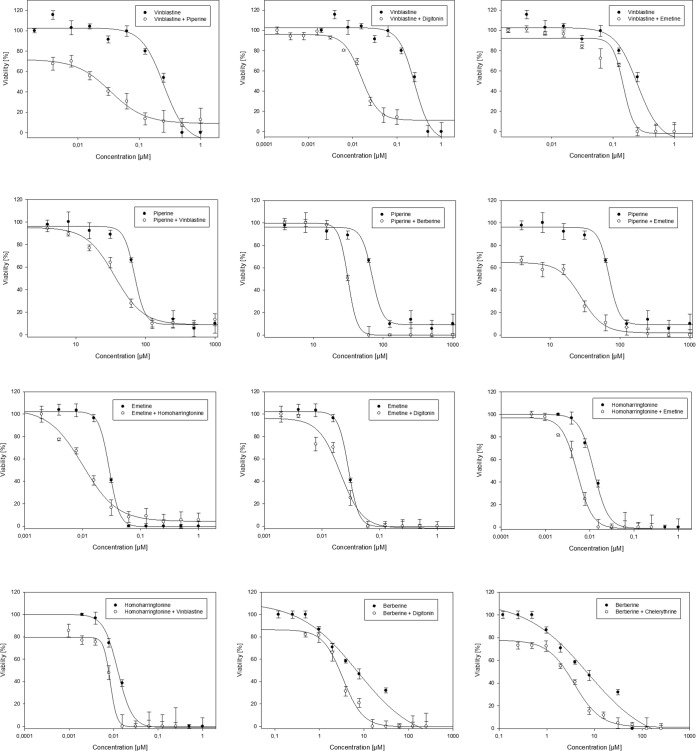

Bloodstream forms of T. b. brucei were treated with a dilution series of mutual combinations of the alkaloids berberine, chelerythrine, emetine, homoharringtonine, piperine, and vinblastine, as well as with combinations of each of those alkaloids with digitonin. The resulting dose dependence of trypanocidal activity is illustrated for some combinations in Fig. 1. IC50s of drugs alone and in combination with the potential enhancer are documented in Table 1. To quantify the interactions among drugs, combination index (CI) values were calculated (Table 2). To better understand the results, an isobologram analysis was done and dose reduction indexes (DRI) were calculated, and the results are illustrated and documented in Fig. 2 and Table 2, respectively.

FIG 1.

Dose dependence of alkaloids alone and in combination with a fixed concentration of another alkaloid or digitonin. Data are represented as means ± SD (expressed as percentages) of cell viability in response to different concentrations of samples.

TABLE 1.

Trypanocidal activity of alkaloids and digitonin alone and in combinations

| Drug | IC50 ± SD of the serially diluted drug alone (μM) | IC50 ± SD of the drug in combination with (μM)a: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berberine (1.87) | Chelerythrine (0.07) | Emetine (0.005) | Homoharringtonine (0.002) | Piperine (14) | Vinblastine (0.04) | Digitonin (0.94) | ||

| Berberine | 6.85 ± 0.82 | 2.80 ± 0.85 | 6.09 ± 0.82 | 4.18 ± 0.35 | 6.05 ± 1.60 | 3.31 ± 0.91 | 2.64 ± 0.63 | |

| Chelerythrine | 0.33 ± 0.006 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 0.30 ± 0.06 | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.27 ± 0.06 | |

| Emetine | 0.03 ± 0.007 | 0.02 ± 0.002 | 0.02 ± 0.001 | 0.01 ± 0.002 | 0.02 ± 0.002 | 0.01 ± 0.004 | 0.01 ± 0.001 | |

| Homoharringtonine | 0.01 ± 0.0002 | 0.009 ± 0.002 | 0.009 ± 0.002 | 0.007 ± 0.002 | 0.01 ± 0.003 | 0.009 ± 0.001 | 0.009 ± 0.002 | |

| Piperine | 72.40 ± 2.43 | 31.88 ± 2.37 | 57.47 ± 11.70 | 16.83 ± 1.94 | 53.31 ± 2.40 | 35.03 ± 1.71 | 55.09 ± 6.75 | |

| Vinblastine | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 0.12 ± 0.007 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.006 | |

| Digitonin | 6.89 ± 0.57 | 4.02 ± 1.09 | 8.39 ± 0.55 | 11.47 ± 0.85 | 6.80 ± 0.90 | 7.03 ± 0.84 | 8.13 ± 1.01 | |

A fixed concentration (indicated in parentheses) was chosen for each combination partner.

TABLE 2.

Summary of the trypanocidal activity of mutual combinations of alkaloids and of alkaloids with digitonina

| Drug | Result for drug added in the combination (nontoxic fixed concn [μM] of the added drug) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berberine (1.87) |

Chelerythrine (0.07) |

Emetine (0.005) |

Homoharringtonine (0.002) |

Piperine (14) |

Vinblastine (0.04) |

Digitonin (0.94) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| CI | IB | DRI | r | CI | IB | DRI | r | CI | IB | DRI | r | CI | IB | DRI | r | CI | IB | DRI | r | CI | IB | DRI | r | CI | IB | DRI | r | |

| Berberine | +++ | syn | 2.44 | 0.93b | ± | ant | 1.12 | 0.96b | ++ | syn | 1.64 | 0.95b | ± | ant | 1.13 | 0.93b | +++ | syn | 2.06 | 0.91b | +++ | syn | 2.59 | 0.91b | ||||

| Chelerythrine | ± | ant | 1.11 | 0.92b | ± | syn | 1.24 | 0.93b | ± | ant | 1.12 | 0.97b | ++ | syn | 1.70 | 0.92b | ± | syn | 1.35 | 0.91b | ± | syn | 1.25 | 0.95b | ||||

| Emetine | ± | ant | 1.30 | 0.91b | ± | syn | 1.34 | 0.93b | +++ | syn | 2.26 | 0.93b | ± | ant | 1.13 | 0.91b | + | syn | 1.51 | 0.96b | ++ | syn | 1.40 | 0.92b | ||||

| Homoharringtonine | ± | syn | 1.47 | 0.95b | ± | syn | 1.41 | 0.97b | ++ | syn | 1.73 | 0.94b | ± | add | 1.25 | 0.99b | + | syn | 1.46 | 0.96b | ++ | syn | 1.41 | 0.94b | ||||

| Piperine | ++ | syn | 2.27 | 0.95b | ± | add | 1.26 | 0.97b | +++ | syn | 4.30 | 0.94b | ± | syn | 1.36 | 0.95b | +++ | syn | 2.07 | 0.96b | + | syn | 1.31 | 0.95b | ||||

| Vinblastine | ++ | syn | 1.80 | 0.90b | −− | ant | 0.96 | 0.96b | ++ | syn | 1.63 | 0.98b | −− | ant | 0.96 | 0.96b | +++ | syn | 7.05 | 0.97b | +++ | syn | 9.07 | 0.96b | ||||

| Digitonin | + | syn | 1.66 | 0.97b | −−− | ant | 0.80 | 0.90b | −−− | ant | 0.58 | 0.86c | −− | ant | 0.98 | 0.94b | −− | ant | 0.95 | 0.93b | −−− | ant | 0.82 | 0.94b | ||||

Summary of synergistic or additive effects of mutual combinations of alkaloids and alkaloids with digitonin. CI values: <0.1, very strong synergism (+++++); 0.1 to 0.3, strong synergism (++++); 0.3 to 0.7, moderately strong synergism (+++); 0.7 to 0.85, moderate synergism (++); 0.85 to 0.90, slight synergism (+); 0.90 to 1.10, nearly additive synergistic effect (±); 1.10 to 1.20, slight antagonism (−); 1.2 to 1.45, moderate antagonism (−−); 1.45 to 3.3, moderately strong antagonism (−−−); 3.3 to 10, strong antagonism (−−−−); >10, very strong antagonism (−−−−−) (14). Isobologram (IB) data were analyzed using isobologram analysis, and the results are reported as follows: syn, synergism; add, additive effect; ant, antagonism. DRI values represent the fold values for the reduction of the dose in a specific combination. Correlation coefficients (r) of the regression lines were calculated, using the basic mass action principle, from the median-effect plots.

P < 0.001.

P < 0.01.

FIG 2.

Isobologram analysis of mutual combinations of alkaloids, and alkaloids with digitonin. y axis represents a drug whose 2-fold serial dilution was used and x axis a drug whose nontoxic concentration was added to the serial dilution. Points located below the line indicate synergy.

Our results clearly show that the investigated combinations of alkaloids can exert a synergistic trypanocidal effect. The addition of a nontoxic concentration of berberine resulted in synergism with piperine and vinblastine, with DRI values of 2.27 and 1.80, respectively (Table 2). Chelerythrine was able to synergistically enhance the activity of berberine, lowering the IC50 from 6.85 to 2.80 μM, with a CI value below 1.

Almost all combinations with vinblastine resulted in a synergistic or additive interaction. The strongest interaction was measured in combination with piperine, with which the trypanocidal effect was increased 7.05-fold (Table 2). Almost any combination of alkaloids with a serial dilution of piperine caused a synergistic enhancement of the trypanocidal activity, with a highest DRI value of 4.30 in a combination with emetine (Table 2). Emetine could synergistically influence the antiparasitic effect of homoharringtonine, piperine, and vinblastine.

The addition of digitonin promoted synergism in almost all combinations. The highest dose reduction index value was measured when digitonin was combined with vinblastine, where the dose was reduced 9.07 times (Table 2). To our surprise, almost all combinations of a fixed concentration of alkaloids with digitonin, except the combination with berberine, were neither synergistic nor additive, with DRI values below 1 (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this study, known bioactive alkaloids were tested in order to determine whether their mutual combinations and combinations with a steroidal saponin, digitonin, could lead to synergistically enhanced antiparasitic activity. Combinations generally resulted in synergistic potentiation of trypanocidal activity.

In our experiments, alkaloids with five different modes of action were combined in a series of experiments in order to determine which combinations result in the strongest synergism. Being one of the strongest membrane-disrupting agents, digitonin was selected as a representative of membrane-permeating compounds (25). The alkaloids indicated in parentheses are associated with DNA intercalation (berberine, chelerythrine, and emetine), induction of apoptosis (piperine), inhibition of the microtubule assembly (vinblastine), and inhibition of protein biosynthesis (homoharringtonine and emetine) (18, 31).

In our previous study (Krstin and Wink, submitted), we were able to show that alkaloids which intercalate DNA, such as chelerythrine, emetine, and berberine, display high trypanocidal activity, with IC50s below 10 μM. Our present results suggest that, in a combination of alkaloids with the same mode of action, namely, intercalation of DNA, the interaction leads to an additive effect rather than synergism. However, the addition of the DNA intercalator chelerythrine to another DNA intercalator, berberine, enhanced the activity of berberine in a synergistic fashion. How to explain the exception? The answer could lie in the fact that berberine and chelerythrine affect a wider range of targets in a cell. Their main activity is focused on DNA, but it has also been demonstrated that they can inhibit protein biosynthesis and induce programmed cell death in human cells and even in trypanosomes (24, 32). It has already been demonstrated that a combination of chelerythrine with mitoxantrone, a drug that also intercalates DNA, exerts additivity, which agrees with the data from this study (33).

In our previous study, homoharringtonine exerted the strongest antitrypanosomal activity, with an IC50 of 10 nM, which is stronger even than that of the trypanocidal drugs used in the study, namely, suramin, diminazene, and pentamidine (Krstin and Wink, submitted). Homoharringtonine is one of the strongest inhibitors of protein biosynthesis known from plants. On the basis of our findings, its addition to a DNA intercalator leads to a higher antitrypanosomal effect. This suggests that the depletion of normal protein synthesis and the intercalation of DNA, which consequently results in stabilization of the double helix, impairment of the replication process, and induction of frameshift mutations, are responsible for a synergistic effect (1). Generally, when a combination of two or more drugs with different mechanisms of action is used, the combination can fight against the disease more effectively (14).

Although piperine has low antitrypanosomal activity, it has been shown that, in higher concentrations, it is able to induce apoptosis in T. b. brucei (32). The addition of any drug to piperine and vice versa resulted in at least additive effects if not synergism. It seems that by inducing apoptosis we can make the trypanosomes more sensitive to almost any drug irrespective of the mechanism.

Vinblastine is a drug that has a high level of antitrypanosomal activity, with an IC50 of 0.21 μM, and whose main mechanism of action is inhibition of the assembly of microtubules by binding to tubulin (1). The highest DRI values seen in this study were calculated when piperine or digitonin was added to a serial dilution of vinblastine. Vinblastine could synergistically enhance the activity of almost all alkaloids in this study. Since movement of the cell is vital for the survival of trypanosomes, our results could be interpreted as meaning that any destabilization of the cytoskeleton could increase the sensitivity of trypanosomes to any other drug. In the case of digitonin, our results show that, by permeating the membrane of a parasitic cell, the trypanocidal activity of almost any alkaloid is increased. A similar finding, in which the uptake of polar drugs was enhanced by the addition of digitonin, has been obtained from human cells (34). The strongest effect was measured when digitonin was added to vinblastine. However, vinblastine is a highly lipophilic drug and can diffuse the membrane easily. Since both compounds (vinblastine and digitonin) are inhibitors of ABC transporters (35, 36), which are also active in trypanosomes (37), we suggest that digitonin inhibits the efflux system and thus increases the internal vinblastine concentrations.

In conclusion, the results presented here show that a combination of individual alkaloids with each other and with digitonin often potentiates trypanocidal activity. This especially applies to combinations of an alkaloid which targets the cytoskeleton and/or membrane with another compound exhibiting another mode(s) of action. Although the mechanisms of some actions seem logical, more studies conducted on a molecular level are necessary to better understand these results. Since we used only two drugs in any one combination, one of the aspects that should be investigated in future work is a combination of three or more substances, which could probably potentiate the antiparasitic activity even more. This in vitro study has given us an insight into which combinations could be interesting for in vivo combination studies, to better understand the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the corresponding drug combinations. However, considering that our results are limited to in vitro conditions, in vivo studies are required to corroborate the synergistic effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Douglas Fear for improving the English language in the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wink M. 2012. Medicinal plants: a source of anti-parasitic secondary metabolites. Molecules 17:12771–12791. doi: 10.3390/molecules171112771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. 2014. Trypanosomiasis, human African (sleeping sickness). World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs259/en/ Accessed 11 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrison LJ. 2011. Parasite-driven pathogenesis in Trypanosoma brucei infections. Parasite Immunol 33:448–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2011.01286.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gehrig S, Efferth T. 2008. Development of drug resistance in Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense and Trypanosoma brucei gambiense. Treatment of human African trypanosomiasis with natural products (review). Int J Mol Med 22:411–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hannaert V. 2011. Sleeping sickness pathogen (Trypanosoma brucei) and natural products: therapeutic targets and screening systems. Planta Med 77:586–597. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1250411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horn D, Duraisingh MT. 2014. Antiparasitic chemotherapy: from genomes to mechanisms. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 54:71–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011613-135915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Wyk B, Wink M. 2004. Medicinal plants of the world. Briza Publications, Pretoria, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santos NN, Menezes LR, dos Santos JA, Meira CS, Guimarhes ET, Soares MB, Nepel A, Barisone A, Costa EV. 2014. A new source of (R)-limonene and rotundifolone from leaves of Lippia pedunculosa (Verbenaceae) and their trypanocidal properties. Nat Prod Commun 9:737–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrmann F, Hamoud R, Sporer F, Tahrani A, Wink M. 2011. Carlina oxide—a natural polyacetylene from Carlina acaulis (Asteraceae) with potent antrypanosomial and antimicrobial properties. Planta Med 77:1905–1911. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1279984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nibret E, Youns M, Krauth-Siegel RL, Wink M. 2011. Biological activities of xanthatin from Xanthium strumarium leaves. Phytother Res 25:1883–1890. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wink M. 2005. Die Verwendung pflanzlicher Vielstoffgemische in der Phytotherapie: eine evolutionaere Sichtweise. Phytotherapie 5:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wink M. 2008. Evolutionary advantage and molecular modes of action of multi-component mixtures used in phytomedicine. Curr Drug Metab 9:996–1009. doi: 10.2174/138920008786927794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinrich M, Maizels D, Gibbons S. 2004. Fundamentals of pharmacognosy and phytotherapy. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou TC. 2006. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol Rev 58:621–681. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts MF, Wink M. 1998. Alkaloids: biochemistry, ecology and medicinal applications. Plenum Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wink M. 1993. Allelochemical properties and the raison d'être of alkaloids. Alkaloids 43:1–118. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wink M. 2000. Interference of alkaloids with neuroreceptors and ion channels. Stud Nat Prod Chem 21:3–129. doi: 10.1016/S1572-5995(00)80004-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wink M. 2007. Molecular modes of action of cytotoxic alkaloids: from DNA intercalation, spindle poisoning, topoisomerase inhibition to apoptosis and multiple drug resistance. Alkaloids Chem Biol 64:1–47. doi: 10.1016/S1099-4831(07)64001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jung Jang E, Kil YS, Ryeon Park H, Oh S, Kyeong Kim H, Gyeong Jeong M, Kyoung Seo E, Sook Hwang E. 2014. Suppression of IL-2 production and proliferation of CD4(+) T cells by tuberostemonine O. Chem Biodivers 11:1954–1962. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201400074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imperatore C, Aiello A, D'Aniello F, Senese M, Menna M. 2014. Alkaloids from marine invertebrates as important leads for anticancer drugs discovery and development. Molecules 19:20391–20423. doi: 10.3390/molecules191220391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haznedaroglu MZ, Gokce G. 2014. Comparison of anti-acetylcholinesterase activity of bulb and leaf extracts of Sternbergia candida Mathew & T. Baytop. Acta Biol Hung 65:396–404. doi: 10.1556/ABiol.65.2014.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eid SY, El-Readi MZ, Wink M. 2012. Digitonin synergistically enhances the cytotoxicity of plant secondary metabolites in cancer cells. Phytomedicine 19:1307–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merschjohann K, Sporer F, Steverding D, Wink M. 2001. In vitro effect of alkaloids on bloodstream forms of Trypanosoma brucei and T. congolense. Planta Med 67:623–627. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wink M, Latz-Brüning B, Schmeller T. 1999. Biochemical effects of allelopathic alkaloids, p 411–422. In Principles and Practices in Plant Ecology. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hellmann JK, Münter S, Wink M, Frischknecht F. 2010. Synergistic and additive effects of epigallocatechin gallate and digitonin on Plasmodium sporozoite survival and motility. PLoS One 5:e8682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baltz T, Baltz D, Giroud C, Crockett J. 1985. Cultivation in a semi-defined medium of animal infective forms of Trypanosoma brucei, T. equiperdum, T. evansi, T. rhodesiense and T. gambiense. EMBO J 4:1273–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosmann T. 1983. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chou TC. 2010. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer Res 70:440–446. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao L, Wientjes MG, Au JL. 2004. Evaluation of combination chemotherapy: integration of nonlinear regression, curve shift, isobologram, and combination index analyses. Clin Cancer Res 10:7994–8004. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chou TC, Talalay P. 1984. Quantitative analysis of dose–effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul 22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wink M, Schimmer O. 2010. Molecular modes of action of defensive secondary metabolites, p 21–161. In Annual plant reviews, volume 39: functions and biotechnology of plant secondary metabolites, 2nd ed. Wiley, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenkranz V, Wink M. 2008. Alkaloids induce programmed cell death in bloodstream forms of trypanosomes (Trypanosoma b. brucei). Molecules 13:2462–2473. doi: 10.3390/molecules13102462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cabrespine A, Bay JO, Barthomeuf C, Curé H, Chollet P, Debiton E. 2005. In vitro assessment of cytotoxic agent combinations for hormone-refractory prostate cancer treatment. Anticancer Drugs 16:417–422. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200504000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jekunen AP, Shalinsky DR, Hom DK, Albright KD, Heath D, Howell SB. 1993. Modulation of cisplatin cytotoxicity by permeabilization of the plasma membrane by digitonin in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol 45:2079–2085. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90019-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eid SY, El-Readi MZ, Eldin EEMN, Fatani SH, Wink M. 2013. Influence of combinations of digitonin with selected phenolics, terpenoids and alkaloids on the expression and activity of P-glycoprotein in leukaemia and colon cancer cells. Phytomedicine 21:47–61. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rautio J, Humphreys JE, Webster LO, Balakrishnan A, Keogh JP, Kunta JR, Serabjit-Singh CJ, Polli JW. 2006. In vitro p-glycoprotein inhibition assay for assessment of clinical drug interaction potential of new drug candidates: a recommendation for probe substrates. Drug Metab Dispos 34:786–792. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.008615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campos MC, Castro-Pinto DB, Ribeiro GA, Berredo-Pinho MM, Gomes LH, da Silva Bellieny MS, Goulart CM, Echevarria A, Leon LL. 2013. P-glycoprotein efflux pump plays an important role in Trypanosoma cruzi drug resistance. Parasitol Res 112:2341–2351. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3398-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]