Abstract

A novel nonconjugative plasmid of 28,489 bp from a porcine linezolid-resistant Enterococcus faecium isolate was completely sequenced. This plasmid harbored a novel type of multiresistance gene cluster that comprised the resistance genes lnu(B), lsa(E), spw, aadE, aphA3, and two copies of erm(B), which account for resistance to macrolides, lincosamides, streptogramins, pleuromutilins, streptomycin, spectinomycin, and kanamycin/neomycin. Structural comparisons suggested that this plasmid might have developed from other enterococcal plasmids by insertion element (IS)-mediated interplasmid recombination processes.

TEXT

During recent years, several ABC transporters were identified in staphylococci, streptococci, and enterococci that confer combined resistance to pleuromutilins, lincosamides, and streptogramin A antibiotics (PLSA). The corresponding genes are vga(A) and vga(A)v (1), vga(C) (2), vga(E) (3), vga(E)v (4), eat(A)v (5), sal(A) (6, 7), lsa(A) (8), lsa(C) (9), and lsa(E) (10). In contrast to the aforementioned genes, the gene lsa(B) confers only elevated MICs to lincosamides which, however, are below the clinical breakpoints for resistance (11). The lsa(E) gene has been identified as part of plasmid-borne or chromosomal multiresistance gene clusters in methicillin-resistant (MRSA) and methicillin-susceptible (MSSA) Staphylococcus aureus (12–14), coagulase-negative or -variable staphylococci (7, 15), and Enterococcus spp. (16) of human and animal origin in Europe and Asia; in human Streptococcus agalactiae from South America (17); and, most recently, in Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae of swine origin in China (18). It is believed that the basic type of these multiresistance gene clusters, which comprises the resistance genes aadE, spw, lsa(E), and lnu(B), has developed in Enterococcus spp. (10, 12, 13). In the present study, a nonconjugative plasmid from Enterococcus faecium that harbors a novel lsa(E)-carrying multiresistance gene cluster was identified and completely sequenced to gain insight into its structure and the genetic environment of lsa(E).

Thirty-five enterococcal strains, including Enterococcus faecalis (n = 21), Enterococcus faecium (n = 13), and Enterococcus gallinarum (n = 1), were isolated from a pig farm in Guangxi province, China. These isolates were investigated for the presence of the lsa(E) gene by PCR using previously described primers (13). The lsa(E) gene was detected in five E. faecalis isolates and one isolate each of E. faecium and E. gallinarum. The lsa(E) nucleotide sequences of the seven isolates were identical to those of lsa(E) on plasmids pV7037 from MRSA ST9 and pXD4 from E. faecium (13, 16). The six E. faecalis and E. faecium isolates were analyzed by multilocus sequence typing (MLST; http://www.mlst.net/). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing by broth microdilution (19, 20) revealed that except for the PLSA phenotype, all isolates were also resistant to erythromycin, tetracycline, streptomycin, gentamicin, kanamycin, and ciprofloxacin but susceptible to ampicillin and vancomycin. Additional resistance (or elevated MICs) to rifampin, florfenicol, or linezolid was seen in five or six of the isolates (Table 1). Linezolid resistance was due to the previously described mutation at position 2576 (G2576T) in the 23S rRNA gene (21), while mutations in genes for the ribosomal proteins L3 and L4 or the cfr gene were detected by PCR and sequence analysis (22, 23).

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of the seven lsa(E)-carrying enterococcal isolates, a transformant, and a recipient strain used in this study

| Strain | MLST type | MIC (mg/liter) fora: |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEN | KAN | VIR M1b | STR | LIN | TIA | VAL | ERY | FFC | TET | CIP | AMP | RIF | VAN | LZD | ||

| E. faecalis 11-27 | ST169 | 128 | >256 | >128 | 128 | 256 | 128 | 128 | >256 | 8 | 64 | 16 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| E. faecalis 12-7 | ST220 | >256 | >256 | >128 | 256 | 256 | 128 | 128 | >256 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 8 |

| E. faecalis 14-1 | ST146 | 256 | >256 | >128 | 256 | 128 | 128 | 128 | >256 | 128 | 128 | 64 | 1 | 16 | 2 | 16 |

| E. faecalis E15 | ST283 | 128 | >256 | >128 | 256 | 128 | 128 | 256 | >256 | 128 | 128 | 64 | 2 | 32 | 2 | 16 |

| E. faecalis D12-2 | ST553 | 128 | >256 | >128 | 128 | 128 | >128 | 256 | >256 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 16 |

| E. gallinarum Y15 | NAc | 256 | >256 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 64 | >256 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 0.5 | 8 | 2 | 8 |

| E. faecium Y13 | ST29 | >256 | >256 | 128 | 256 | 128 | >128 | 128 | >256 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 16 |

| E. faecalis TY13d | 2 | >256 | 128 | 256 | 128 | >128 | 128 | >256 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ≤0.5 | 2 | |

| E. faecalis JH2-2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

GEN, gentamicin; STR, streptomycin; KAN, kanamycin; VIR M1, virginiamycin M1; LIN, lincomycin; TIA, tiamulin; VAL, valnemulin; ERY, erythromycin; FFC, florfenicol; TET, tetracycline; CIP, ciprofloxacin; AMP, ampicillin; RIF, rifampin; VAN, vancomycin; LZD, linezolid.

Note that E. faecalis is intrinsically resistant to streptogramins.

NA, not applicable.

TY13 was the transformant derived from transformation of plasmid pY13 from E. faecium Y13 into E. faecalis JH2-2.

Conjugations by filter mating and transformation experiments were conducted using E. faecalis JH2-2 as the recipient (24). The two E. faecium plasmids pXD4 and pN39 served as positive controls in transformation and conjugation experiments (16). Transconjugants and transformants were selected on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar supplemented with 10 mg/liter valnemulin and 50 mg/liter rifampin. Only one of the lsa(E)-positive enterococcal isolates, namely, E. faecium Y13, yielded a transformant after electrotransformation. This transformant (designated TY13) exhibited high MICs not only for tiamulin, valnemulin, lincomycin, and virginiamycin M1 but also for erythromycin, kanamycin, and streptomycin (Table 1). S1 nuclease pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) combined with Southern blot analysis revealed that the lsa(E) gene was located on a ca. 28-kb plasmid, designated pY13. This plasmid was sequenced using the 454 Life Sciences GS FLX system (Roche), and sequence assembly was further confirmed by nine overlapping PCR assays (PCR1 to PCR9) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Plasmid sequence analyses, comparisons, and annotations were performed as previously described (23). The complete plasmid pY13 from E. faecium Y13 was 28,489 bp in size and contained 30 putative open reading frames (ORFs) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Based on the classification system for plasmids from enterococci and other Gram-positive bacteria described by Jensen et al. (25), plasmid pY13 is a member of the rep1 family of plasmids.

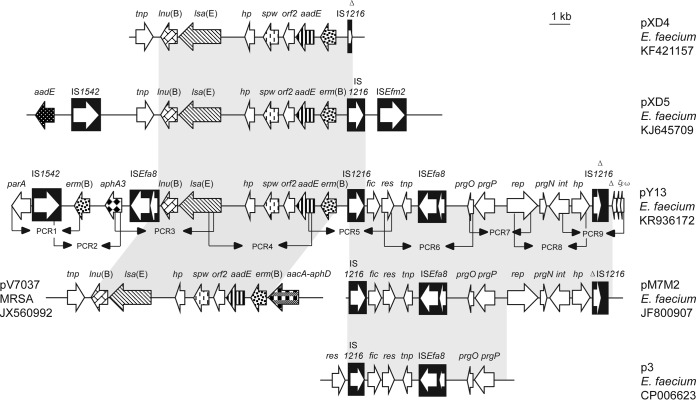

Sequence comparisons revealed a 12,461-bp region in pY13 that contained ORFs involved in plasmid replication, maintenance, and transfer and exhibited >99% identity to plasmid pM7M2 from a dairy-derived E. faecium isolate (26) (Fig. 1). Within this region, a 7,118-bp segment showed >99% identity to the corresponding sequence of plasmid p3 from a vancomycin-resistant E. faecium ST203 isolate of human origin (27). Upstream of an ISEfa8 element, a prgOPN gene cluster was detected. Previous studies demonstrated that the prgOPN gene cluster may represent a toxin-antitoxin–independent stabilization mechanism and may be involved in the persistence and distribution of antibiotic resistance plasmids (28, 29). The prgP-prgO genes may represent the most common partition cassettes in enterococci (30).

FIG 1.

Linear comparison of the lsa(E)-carrying plasmid pY13 (GenBank accession no. KR936172) with enterococcal and staphylococcal plasmids pXD4, pXD5, pM7M2, pV7037, and p3. Arrows, positions and directions of transcription of the genes; shading, regions of >99% nucleotide sequence identity in the different plasmids; black arrowheads, the nine overlapping PCRs (PCR1 to PCR9) designed to confirm the pY13 plasmid and the genetic environment of the lsa(E) gene; Δ, a truncated gene.

A region of 8,705 bp in pY13, which is bracketed on the left-hand side by an ISEfa8 element and on the right-hand side by an IS1216 element, contains the five antimicrobial resistance genes lnu(B) (lincosamide resistance), lsa(E) (PLSA resistance), spw (spectinomycin resistance), aadE (streptomycin resistance), and erm(B) (macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance). This region corresponded closely to the regions identified on plasmid pV7037 from MRSA ST9 (13) and on plasmids pXD4 (16) and pXD5 (31) from E. faecium (Fig. 1). Further downstream of lnu(B), an aphA3 gene for kanamycin/neomycin resistance and another copy of the erm(B) gene were detected in the pY13 sequence (Fig. 1). The MICs of the transformant TY13 (Table 1) indicated that all six antimicrobial resistance genes of plasmid pY13 are functionally active. Structural comparisons suggested that pY13 is composed of various segments, which have been found, at least in part, on other enterococcal or staphylococcal plasmids (Fig. 1). Since all of these segments are flanked by intact or truncated insertion sequences, it is possible that pY13 developed from interplasmidic recombination events in which insertion sequences, such as ISEfa8, IS1216, and IS1542, have been involved.

S1 nuclease-PFGE combined with Southern blotting revealed that the lsa(E) gene was also located on plasmids of ca. 28 kb in the remaining five E. faecalis isolates and on a plasmid of ca. 40 kb in the E. gallinarum isolate (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). To investigate whether a pY13-like plasmid is present in these isolates, eight overlapping PCRs were designed (Fig. 1, PCR1 to PCR9; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material) to amplify eight partly overlapping regions covering the entire sequence of pY13. Subsequently, the purified PCR products were cloned into the vector pEASY-T1 and then sequenced by primer walking (Invitrogen, Beijing, China). Results showed that all five E. faecalis strains carried virtually the same pY13-like plasmid except for a few nucleotide substitutions, whereas the E. gallinarum strain was only positive for PCR3 to PCR6. Although the reason(s) that these pY13-like plasmids were not transferrable by electrotransformation into E. faecalis JH2-2 remains to be elucidated, these observations suggested that pY13-like plasmids have spread among different E. faecalis strains and play a role in the dissemination of lsa(E)-carrying multiresistance gene clusters.

In conclusion, we report the first complete sequence of a lsa(E)-harboring plasmid from an E. faecium isolate of swine origin. Although nonconjugative, pY13-like plasmids may act as vectors in the dissemination of antimicrobial multiresistance within the Gram-positive gene pool.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of plasmid pY13 has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. KR936172. The sequences of the five pY13-like plasmids from E. faecalis, i.e., p11-27 (28,489 bp) (KT448817), pE15 (28,490 bp) (KT448821), p12-7 (28,491 bp) (KT448818), pD12 (28,491 bp) (KT448820), and p14-1 (28,492 bp) (KT448819), as well as the sequence of a 15,464-bp segment of plasmid pY15 (KT448822) from E. gallinarum, have also been deposited in GenBank.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation Programs (2012GXNSFBA053052 and 2013GXNSFAA019070) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31201862).

The contribution of S.S. was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) through the German Aerospace Center (DLR) (01KI1301D [MedVet-Staph II]).

We thank X. D. Du (Henan Agricultural University) for providing plasmids pXD4 and pN39 as controls for conjugation and transformation experiments.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01394-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gentry DR, McCloskey L, Gwynn MN, Rittenhouse SF, Scangarella N, Shawar R, Holmes DJ. 2008. Genetic characterization of Vga ABC proteins conferring reduced susceptibility to pleuromutilins in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:4507–4509. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00915-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kadlec K, Schwarz S. 2009. Novel ABC transporter gene, vga(C), located on a multiresistance plasmid from a porcine methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:3589–3591. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00570-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwendener S, Perreten V. 2011. New transposon Tn6133 in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 contains vga(E), a novel streptogramin A, pleuromutilin, and lincosamide resistance gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4900–4904. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00528-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li J, Li B, Wendlandt S, Schwarz S, Wang Y, Wu C, Ma Z, Shen J. 2014. Identification of a novel vga(E) gene variant that confers resistance to pleuromutilins, lincosamides and streptogramin A antibiotics in staphylococci of porcine origin. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:919–923. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isnard C, Malbruny B, Leclercq R, Cattoir V. 2013. Genetic basis for in vitro and in vivo resistance to lincosamides, streptogramins A, and pleuromutilins (LSAP phenotype) in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:4463–4469. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01030-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hot C, Berthet N, Chesneau O. 2014. Characterization of sal(A), a novel gene responsible for lincosamide and streptogramin A resistance in Staphylococcus sciuri. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3335–3341. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02797-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wendlandt S, Kadlec K, Feßler AT, Schwarz S. 2015. Identification of ABC transporter genes conferring combined pleuromutilin-lincosamide-streptogramin A resistance in bovine methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci. Vet Microbiol 177:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh KV, Weinstock GM, Murray BE. 2002. An Enterococcus faecalis ABC homologue (Lsa) is required for the resistance of this species to clindamycin and quinupristin-dalfopristin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:1845–1850. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1845-1850.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malbruny B, Werno AM, Murdoch DR, Leclercq R, Cattoir V. 2011. Cross-resistance to lincosamides, streptogramins A, and pleuromutilins due to the lsa(C) gene in Streptococcus agalactiae UCN70. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:1470–1474. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01068-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wendlandt S, Lozano C, Kadlec K, Gomez-Sanz E, Zarazaga M, Torres C, Schwarz S. 2013. The enterococcal ABC transporter gene lsa(E) confers combined resistance to lincosamides, pleuromutilins and streptogramin A antibiotics in methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:473–475. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kehrenberg C, Ojo KK, Schwarz S. 2004. Nucleotide sequence and organization of the multiresistance plasmid pSCFS1 from Staphylococcus sciuri. J Antimicrob Chemother 54:936–939. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lozano C, Aspiroz C, Saenz Y, Ruiz-Garcia M, Royo-Garcia G, Gomez-Sanz E, Ruiz-Larrea F, Zarazaga M, Torres C. 2012. Genetic environment and location of the lnu(A) and lnu(B) genes in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and other staphylococci of animal and human origin. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:2804–2808. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li B, Wendlandt S, Yao J, Liu Y, Zhang Q, Shi Z, Wei J, Shao D, Schwarz S, Wang S, Ma Z. 2013. Detection and new genetic environment of the pleuromutilin-lincosamide-streptogramin A resistance gene lsa(E) in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus of swine origin. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:1251–1255. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wendlandt S, Li J, Ho J, Porta MA, Feßler AT, Wang Y, Kadlec K, Monecke S, Ehricht R, Boost M, Schwarz S. 2014. Enterococcal multiresistance gene cluster in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from various origins and geographical locations. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:2573–2575. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva NC, Guimarães FF, de Manzi PM, Gómez-Sanz E, Gómez P, Araújo-Júnior JP, Langoni H, Rall VL, Torres C. 2014. Characterization of methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci in milk from cows with mastitis in Brazil. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 106:227–233. doi: 10.1007/s10482-014-0185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li XS, Dong WC, Wang XM, Hu GZ, Wang YB, Cai BY, Wu CM, Wang Y, Du XD. 2014. Presence and genetic environment of pleuromutilin-lincosamide-streptogramin A resistance gene lsa(E) in enterococci of human and swine origin. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:1424–1426. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montilla A, Zavala A, Cáceres Cáceres R, Cittadini R, Vay C, Gutkind G, Famiglietti A, Bonofiglio L, Mollerach M. 2014. Genetic environment of the lnu(B) gene in a Streptococcus agalactiae clinical isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:5636–5637. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02630-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang A, Xu C, Wang H, Lei C, Liu B, Guan Z, Yang C, Yang Y, Peng L. 2015. Presence and new genetic environment of pleuromutilin-lincosamide-streptogramin A resistance gene lsa(E) in Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae of swine origin. Vet Microbiol 177:162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2013. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria isolated from animals; 2nd informational supplement CLSI document VET01-S2. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2013. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 23rd informational supplement CLSI document M100-S23. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tewhey R, Gu B, Kelesidis T, Charlton C, Bobenchik A, Hindler J, Schork NJ, Humphries RM. 2014. Mechanisms of linezolid resistance among coagulase-negative staphylococci determined by whole-genome sequencing. mBio 5:e00894-4. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00894-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel SN, Memari N, Shahinas D, Toye B, Jamieson FB, Farrell DJ. 2013. Linezolid resistance in Enterococcus faecium isolated in Ontario, Canada. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 77:350–353. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang WJ, Wang XM, Dai L, Hua X, Dong Z, Schwarz S, Liu S. 2015. Novel conjugative plasmid from Escherichia coli of swine origin that coharbors the multiresistance gene cfr and the extended-spectrum-β-lactamase gene blaCTX-M-14b. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:1337–1340. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04631-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu H, Wang Y, Wu C, Schwarz S, Shen Z, Jeon B, Ding S, Zhang Q, Shen J. 2012. A novel phenicol exporter gene, fexB, found in enterococci of animal origin. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:322–325. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen LB, Garcia-Migura L, Valenzuela AJS, Løhr M, Hasman H, Aarestrup FM. 2010. A classification system for plasmids from enterococci and other Gram-positive bacteria. J Microbiol Methods 80:25–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Alvarez V, Harper WJ, Wang HH. 2011. Persistent, toxin-antitoxin system-independent, tetracycline resistance-encoding plasmid from a dairy Enterococcus faecium isolate. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:7096–7103. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05168-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lam MM, Seemann T, Tobias NJ, Chen H, Haring V, Moore RJ, Ballard S, Grayson LM, Johnson PD, Howden BP, Stinear TP. 2013. Comparative analysis of the complete genome of an epidemic hospital sequence type 203 clone of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. BMC Genomics 14:595. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moritz EM, Hergenrother PJ. 2007. Toxin-antitoxin systems are ubiquitous and plasmid-encoded in vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:311–316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601168104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sletvold H, Johnsen PJ, Wikmark OG, Simonsen GS, Sundsfjord A, Nielsen KM. 2010. Tn1546 is part of a larger plasmid-encoded genetic unit horizontally disseminated among clonal Enterococcus faecium lineages. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:1894–1906. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clewell DB, Weaver KE, Dunny GM, Coque TM, Francia MV, Hayes F. 2014. Extrachromosomal and mobile elements in enterococci: transmission, maintenance, and epidemiology. In Gilmore MS, Clewell DB, Ike Y, Shankar N (ed), Enterococci: from commensals to leading causes of drug resistant infection. Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Boston, MA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang XM, Li XS, Wang YB, Wei FS, Zhang SM, Shang YH, Du XD. 2015. Characterization of a multidrug resistance plasmid from Enterococcus faecium that harbours a mobilized bcrABDR locus. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:609–611. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.