Abstract

We analyzed the oxacillinases of isolates of six different species of Pandoraea, a genus that colonizes the respiratory tract of cystic fibrosis patients. The isolates produced carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzymes causing elevated MICs for amoxicillin, piperacillin, meropenem, and imipenem when expressed in an Escherichia coli host strain. Sequencing revealed nine new oxacillinases (OXA-151 to OXA-159) with a high degree of identity among isolates of the same species; however, they had much lower interspecies similarities. The intrinsic oxacillinase genes might therefore be helpful for correct identification of Pandoraea isolates.

TEXT

Oxacillinases are serine β-lactamases of the molecular class D, which currently comprises more than 480 enzymes (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogen/betalactamases/Lahey.tab; last accessed in August 2015) showing a high degree of variability both in their amino acid sequences as well as in their activities against β-lactams. Their impact on antibiotic resistance has long been considered low; however, during the last 15 years, the prevalence of carbapenem-hydrolyzing variants has increased (1). Furthermore, the number of OXA-type enzymes, which have been found to be intrinsically produced by a broad range of bacterial species, is rising, and among them are several enzymes with carbapenem-hydrolyzing activity: e.g., OXA-51-like from Acinetobacter baumanii, OXA-228-like from Acinetobacter bereziniae, OXA-213-like from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, OXA-214-like from Acinetobacter haemolyticus, OXA-211-like from Acinetobacter johnsonii, OXA-134 from Acinetobacter lwoffii, OXA-23-like from Acinetobacter radioresistens, OXA-54 from Shewanella oneidensis, and OXA-55 from Shewanella algae (2–6). Another intrinsic carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase is OXA-62 from Pandoraea pnomenusa (7).

Pandoraea spp. are Gram-negative, glucose-nonfermenting rods closely related to Burkholderia and Ralstonia (8). Isolates of the genus Pandoraea were shown to colonize the respiratory tract predominantly of cystic fibrosis patients (9–11), with the potential to cause severe deterioration of lung function or septicemia in some cases (12–16). Antimicrobial therapy of infections caused by Pandoraea spp. is impaired by their broad resistance to antibiotics (7, 9, 11). In this study, the oxacillinases of nine isolates of six Pandoraea species were analyzed.

The isolates H4-1-1, E126-13, Va8523, and HD7676 obtained from sputa of cystic fibrosis patients from Germany (7), were identified by phenotypic (API 20 NE [bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France] and additional biochemical tests) and genotypic methods (in-house PCR assay with species-specific oligonucleotides based on published 16S rRNA and gyrB gene sequences). Pandoraea isolates LMG 16407, LMG 18379, LMG 18087, LMG 18106, and LMG 18819 were obtained from Laboratorium voor Microbiologie (Universiteit Ghent, Ghent, Belgium). Pandoraea sputorum LMG 18100 (C4964) was provided by D. P. Speert, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. A previously obtained Escherichia coli transformant producing OXA-62 (7) was included for comparison.

MICs were determined by an agar dilution technique following CLSI guidelines (17). The β-lactamase inhibitors tazobactam and BRL 42715, an inhibitor of active-site serine β-lactamases (18), were used at a concentration of 4 μg/ml. Similar to the findings of several investigators (11–13, 15, 16), our Pandoraea isolates showed broad resistance to β-lactams as well as to non-β-lactam compounds (Table 1). Tazobactam showed only a marginal inhibitory effect, while BRL 42715 had a strong inhibitory effect in combination with amoxicillin and meropenem.

TABLE 1.

Antibiotic susceptibilities and pIs of β-lactamases of Pandoraea isolates

| Parameter and antibiotica | Result for: |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

P. pnomenusa |

P. apista LMG 16407T OXA-153 | P. norimbergensis LMG 18379T OXA-157 | P. pulmonicola LMG 18106T OXA-156 |

P. sputorum |

Pandoraea |

|||||

| H4-1-1 OXA-62 | E126-13 OXA-152 | LMG 18087T OXA-151 | LMG 18819T OXA-154 | LMG 18100 OXA-155 | Va8523 OXA-158 | HD7676 OXA-159 | ||||

| MIC (μg/ml) | ||||||||||

| AMX | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 |

| AMX + BRL | 32 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 4 |

| PIP | >512 | 512 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 512 | >512 | >512 | 512 | >512 |

| PIP + TZB | >512 | 256 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 512 | >512 | 128 | 512 | 128 |

| CAZ | 256 | 256 | 256 | 128 | 128 | 128 | >256 | >256 | 256 | 128 |

| CAZ + BRL | 256 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 128 | 128 | >256 | 256 | 128 | 128 |

| CTX | 64 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 32 | 128 | 32 | 32 | 16 |

| FOX | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| ATM | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 |

| MEM | 1024 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

| MEM + BRL | 16 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| IPM | 64 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| IPM + BRL | 8 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.13 |

| GEN | >128 | >128 | >128 | 128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| TOB | >128 | >128 | >128 | 64 | 128 | >128 | >128 | 128 | >128 | >128 |

| CIP | 8 | 16 | 8 | 64 | 4 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 32 |

| SXT | >256 | 64 | 32 | 4 | 16 | 16 | 32 | 2 | 16 | 32 |

| CHL | 64 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 64 | 32 | 32 | 128 | 32 |

| TET | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 256 | 4 | 4 | 256 | 64 |

| pI of β-lactamase(s)b | 7.4, 8.0, >9.0 | 6.5, >9.0 | 6.7, 7.7, >9.0 | 7.4, 8.5 | 8.8 | 8.0, 8.4 | 8.4, 8.8 | 8.0, 8.8 | 7.0, 7.6, 8.9 | 7.0, 7.6, 8.9 |

Abbreviations: AMX, amoxicillin; BRL, BRL 42715; PIP, piperacillin; TZB, tazobactam; CAZ, ceftazidime; CTX, cefotaxime; FOX, cefoxitin; ATM, aztreonam; MEM, meropenem; IPM, imipenem; GEN, gentamicin; TOB, tobramycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; CHL, chloramphenicol; TET, tetracycline.

The pI values of carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases identified by bioassay are indicated in boldface.

Sonication of strain suspensions, isoelectric focusing, and assessment of the hydrolytic activity by a bioassay were performed as described previously (7). The Pandoraea isolates produced between one and three β-lactamases, and all isolates showed a carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzyme focusing on pIs of ≥8.0 (Table 1).

For cloning of the β-lactamase genes, whole-cell DNA of the isolates was extracted using the GFX Genomic DNA purification kit (Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany), partially digested with Sau3AI, and ligated into BamHI-digested pBC-SK+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The ligation product was transformed into E. coli DH5α by electroporation. Transformants were selected on tryptic soy agar containing ampicillin (32 μg/ml). The cloned DNA fragments were sequenced by primer walking (Eurofins MWG Operon, Ebersberg, Germany). Additionally, the blaOXA genes of Pandoraea isolates E126-13, LMG 18087, and LMG 18100 were sequenced using oligonucleotides deduced from the sequences of the cloned DNA fragments. Sequence analyses and multiple alignments were performed using Chromas Lite 2.01 (Technelysium Pty Ltd., Brisbane, Australia) and DNAMAN 4.1 (Lynnon BioSoft, Vaudreuil-Dorion, Canada).

All E. coli DH5α transformants showed amoxicillin MICs above 256 μg/ml, which were strongly reduced by the addition of BRL 42715 (Table 2). Piperacillin MICs ranged from 32 to 256 μg/ml and were reduced 8 to 256-fold by tazobactam. Such a strong inhibitory effect of tazobactam could not be seen for the wild-type isolates. The MICs of ceftazidime, cefotaxime, cefoxitin, and aztreonam were only marginally affected by the introduction of the recombinant plasmids into E. coli DH5α. The meropenem and imipenem MICs were elevated up to 16- or 4-fold, respectively, by the expression of the OXA enzymes. The addition of BRL 42715 reduced the MICs for meropenem and imipenem to the levels of the host strain. As the effect of the expression of β-lactamases on the carbapenem MICs of fully susceptible E. coli hosts is often very small, we additionally transformed the recombinant plasmids into a Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis host strain lacking an outer membrane protein (Table 2). This resulted in a more pronounced increase of the MICs for meropenem (256-fold) and imipenem (16-fold) in comparison to those of the E. coli host.

TABLE 2.

Antibiotic susceptibilities of transformants producing oxacillinases derived from Pandoraea species

| Transformant or host strain | Oxacillinase | MIC (μg/ml) fora: |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. coli DH5α |

S. enterica

serovar Enteritidis 104.773 |

|||||||||||||||

| AMX | AMX + BRL | PIP | PIP + TZB | CAZ | CAZ + BRL | CTX | FOX | ATM | MEM | MEM + BRL | IMP | IPM + BRL | MEM | IMP | ||

| Transformant strain plasmids | ||||||||||||||||

| pT6 | OXA-62 | >256 | 0.5 | 64 | 4 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 |

| pT89 | OXA-153 | >256 | 0.5 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 4 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 1 |

| pT90 | OXA-156 | >256 | 0.5 | 256 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 4 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 1 | 1 |

| pT100 | OXA-154 | >256 | 0.5 | 256 | 4 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 8 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.016 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 1 | 1 |

| pT103 | OXA-157 | >256 | 0.5 | 128 | 2 | 0.13 | ≤0.03 | 0.06 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.016 | 0.5 | ≤0.06 | 2 | 2 |

| pT104 | OXA-158 | >256 | 0.5 | 256 | 8 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 4 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.13 | 4 | 2 |

| pT106 | OXA-159 | >256 | 0.5 | 256 | 8 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 8 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.016 | 0.5 | 0.13 | 2 | 1 |

| Host strains | 8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 4 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.016 | 0.13 | |

Abbreviations: AMX, amoxicillin; BRL, BRL 42715; PIP, piperacillin; TZB, tazobactam; CAZ, ceftazidime; CTX, cefotaxime; FOX, cefoxitin; ATM, aztreonam; MEM, meropenem; IPM, imipenem.

The seven recombinant plasmids harbored inserts of 1.5 to 2.5 kb with open reading frames corresponding to class D β-lactamases. The G+C content of the blaOXA genes ranged between 60 and 65%, and that of the environmental sequences ranged between 60 and 67%, which is close to the values for Pandoraea spp. (61.2 to 64.3%) published by Coenye et al. (8).

The putative promoter sequences are located between 88 and 135 bp upstream of the start codon. The promoter sequences are identical for genes derived from the same species; however, they vary among the genes of different species.

The regions upstream and downstream, respectively, of the oxacillinase genes corresponded to a “hypothetical protein” and to an NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase gene also present in two P. pnomenusa genome sequences (CP006900 and CP007506). Comparable sequences upstream of β-lactamase genes are present in the genomes of several isolates of different species, e.g., Ralstonia pickettii (CP006668), Ralstonia eutropha (AM260480), and Cupriavidus taiwanensis (CU633750).

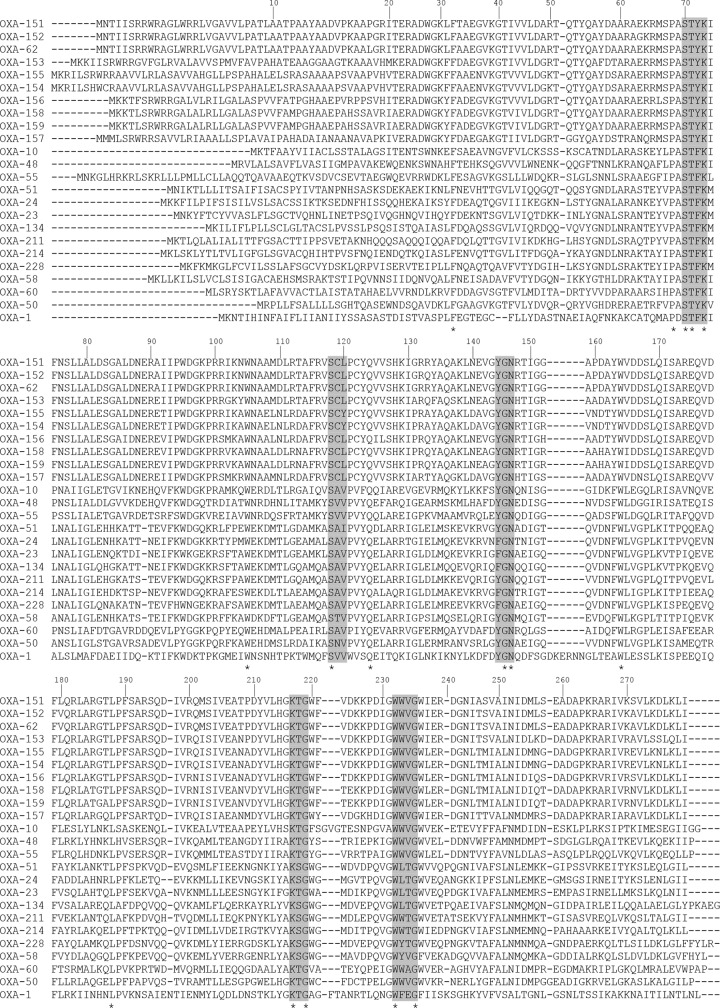

The nine Pandoraea-derived oxacillinase genes encoded proteins of 283 to 292 amino acids, which were found to be new oxacillinase variants, namely, OXA-151 to OXA-159. They showed the structural elements characteristic for class D β-lactamases (Fig. 1), as follows. At positions 70 to 73 (class D β-lactamase-numbering, DBL) (19) the STYK tetrad was found, which is also present in enzymes of the OXA-50 subgroup, in contrast to the STFK motif, which is most common among oxacillinases. Within the usual SXV motif (positions 118 to 120), valine was replaced by leucine, except for OXA-154 and OXA-155 from P. sputorum, where valine was replaced by tyrosine. The Pandoraea oxacillinases showed the YGN motif at positions 144 to 146 and the KTG motif at positions 216 to 218, like most of the class D β-lactamases, in contrast to the motifs FGN and KSG, which were found in some of the carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D enzymes. The common WXXG motif at positions 232 to 235 was found as in all oxacillinases.

FIG 1.

Comparison of the amino acid sequences of OXA-151 to OXA-159 with those of other carbapenem-hydrolyzing class D β-lactamases and those of OXA-1 and OXA-10. Identical residues are marked by asterisks, and motifs conserved among oxacillinases are shaded. The amino acid positions are numbered according to the DBL system (19).

The amino acid sequence similarities for OXA-151 to OXA-159, including the previously described OXA-62 from P. pnomenusa (7) and the respective regions of the two P. pnomenusa genome sequences, ranged between 71.5 and 99.6%. In comparison to other oxacillinases, OXA-151 to OXA-159 showed the highest similarities (36 to 45%) to the intrinsic enzymes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (OXA-50) (20) and Shewanella algae (OXA-55) (2), to the acquired β-lactamases OXA-2 and OXA-20, as well as to enzymes of several genome sequences of bacteria of different phyla: e.g., Parvibaculum lavamentivorans (NC009719), Acaryochloris marina (NC009925), Idiomarina loihiensis (NC006512), Methylobacillus flagellatus (CP000284), and Streptosporangium roseum (CP001814).

Accurate identification of pathogens to the species level is mandatory for epidemiological analysis and the implementation of measures to prevent spread of isolates among cystic fibrosis patients. However, members of the genus Pandoraea are difficult to identify by conventional biochemical methods (11, 15, 21, 22). Molecular methods based on 16S rRNA are helpful to differentiate Pandoraea from closely related genera like Burkholderia and Ralstonia; however, they are not able to discriminate accurately between the Pandoraea species (23, 24). Coenye et al. (25) found gyrB gene sequences helpful to differentiate among Pandoraea species, while the applicability of the recA gene, which is also commonly used for phylogenetic analysis, seems to be limited (26). Using sequences of the NCBI database, we compared the nucleotide sequence similarities for 16S rRNA, gyrB, and blaOXA genes for isolates of different Pandoraea species. All three genes showed high similarities (96.1 to 100%) for isolates belonging to the same species. In contrast, interspecies similarities showed larger variations: 97.2 to 99.8% for 16S rRNA, 84.6 to 97.3% for gyrB, and 71.8 to 87.7% for blaOXA. So, the oxacillinase genes showed the broadest interspecies variability and along with their high degree of intraspecies similarities (98.5 to 99.8%), they might pose an opportunity for species identification by molecular techniques.

As the Pandoraea isolates Va8523 and HD7676 were not identifiable to the species level, a 970-bp fragment of their gyrB genes was sequenced. The sequences showed high similarity (99.8%) and formed a separate branch in a phylogenetic tree with additional 19 gyrB gene sequences from isolates of eight Pandoraea species obtained from the NCBI database (data not shown). Therefore, the isolates Va8523 and HD7676 seem to belong to the same species, which is different from the Pandoraea species described until now. The oxacillinase genes of those two isolates (OXA-158 and OXA-159) showed 99.5% nucleotide sequence identity and clearly differed from the oxacillinases of the other Pandoraea spp. (75.1 to 87.7% similarity). So, similar to the gyrB genes, the oxacillinase genes of those two isolates form a distinct branch in the oxacillinase gene homology tree (data not shown), supporting the assumption that they may belong to a separate species not yet identified.

In conclusion, our study showed the intrinsic production of carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinases by Pandoraea isolates of various species. The oxacillinases, which contribute to the resistance to aminopenicillins and carbapenems, seem to be species specific and may therefore be helpful for the identification of members of the genus Pandoraea up to the species level. Our work indicates that Pandoraea species are contributing to the natural reservoir of carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinases that may serve as progenitors of acquired β-lactamases, as has been the case for the OXA-23-like enzymes of A. radioresistens (27).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the blaOXA genes have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. KP771979 (OXA-151), KP771980 (OXA-152), KP771981 (OXA-153), KP771982 (OXA-154), KP771983 (OXA-155), KP771984 (OXA-156), KP771985 (OXA-157), KP771986 (OXA-158), and KP771987 (OXA-159).

This article is dedicated to the memory of Adolf Bauernfeind.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patel G, Bonomo RA. 2013. “Stormy waters ahead”: global emergence of carbapenemases. Front Microbiol 4:48. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Héritier C, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2004. Genetic and biochemical characterization of a chromosome-encoded carbapenem-hydrolyzing ambler class D β-lactamase from Shewanella algae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:1670–1675. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1670-1675.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poirel L, Naas T, Nordmann P. 2010. Diversity, epidemiology, and genetics of class D β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:24–38. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01512-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonnin RA, Ocampo-Sosa AA, Poirel L, Guet-Revillet H, Nordmann P. 2012. Biochemical and genetic characterization of carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase OXA-229 from Acinetobacter bereziniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:3923–3927. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00257-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Figueiredo S, Bonnin RA, Poirel L, Duranteau J, Nordmann P. 2012. Identification of the naturally occurring genes encoding carbapenem-hydrolysing oxacillinases from Acinetobacter haemolyticus, Acinetobacter johnsonii, and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:907–913. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poirel L, Héritier C, Nordmann P. 2004. Chromosome-encoded ambler class D β-lactamase of Shewanella oneidensis as a progenitor of carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:348–351. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.1.348-351.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider I, Queenan AM, Bauernfeind A. 2006. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase OXA-62 from Pandoraea pnomenusa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:1330–1335. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1330-1335.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coenye T, Falsen E, Hoste B, Ohlén M, Goris J, Govan JR, Gillis M, Vandamme P. 2000. Description of Pandoraea gen. nov. with Pandoraea apista sp. nov., Pandoraea pulmonicola sp. nov., Pandoraea pnomenusa sp. nov., Pandoraea sputorum sp. nov. and Pandoraea norimbergensis comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 50:887–899. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-2-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atkinson RM, LiPuma JJ, Rosenbluth DB, Dunne WM Jr. 2006. Chronic colonization with Pandoraea apista in cystic fibrosis patients determined by repetitive-element-sequence PCR. J Clin Microbiol 44:833–836. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.833-836.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daneshvar MI, Hollis DG, Steigerwalt AG, Whitney AM, Spangler L, Douglas MP, Jordan JG, MacGregor JP, Hill BC, Tenover FC, Brenner DJ, Weyant RS. 2001. Assignment of CDC weak oxidizer group 2 (WO-2) to the genus Pandoraea and characterization of three new Pandoraea genomospecies. J Clin Microbiol 39:1819–1826. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.5.1819-1826.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernández-Olmos A, Morosini MI, Lamas A, García-Castillo M, García-García L, Cantón R, Máiz L. 2012. Clinical and microbiological features of a cystic fibrosis patient chronically colonized with Pandoraea sputorum identified by combining 16S rRNA sequencing and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol 50:1096–1098. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05730-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson LN, Han JY, Moskowitz SM, Burns JL, Qin X, Englund JA. 2004. Pandoraea bacteremia in a cystic fibrosis patient with associated systemic illness. Pediatr Infect Dis J 23:881–882. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000136857.74561.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jørgensen IM, Johansen HK, Frederiksen B, Pressler T, Hansen A, Vandamme P, Høiby N, Koch C. 2003. Epidemic spread of Pandoraea apista, a new pathogen causing severe lung disease in cystic fibrosis patients. Pediatr Pulmonol 36:439–446. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martínez-Lamas L, Rabade Castedo C, Martín Romero Domínguez M, Barbeito Castiñeiras G, Palacios Bartolomé A, Pérez Del Molino Bernal ML. 2011. Pandoraea sputorum colonization in a patient with cystic fibrosis. Arch Bronconeumol 47:571–574. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2011.06.015 (In Spanish.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore JE, Reid A, Millar BC, Jiru X, Mccaughan J, Goldsmith CE, Collins J, Murphy PG, Elborn JS. 2002. Pandoraea apista isolated from a patient with cystic fibrosis: problems associated with laboratory identification. Br J Biomed Sci 59:164–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stryjewski ME, LiPuma JJ, Messier RH Jr, Reller LB, Alexander BD. 2003. Sepsis, multiple organ failure, and death due to Pandoraea pnomenusa infection after lung transplantation. J Clin Microbiol 41:2255–2257. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.5.2255-2257.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2012. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 22nd informational supplement M100-S22. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matagne A, Ledent P, Monnaie D, Felici A, Jamin M, Raquet X, Galleni M, Klein D, François I, Frère JM. 1995. Kinetic study of interaction between BRL 42715, beta-lactamases, and d-alanyl-d-alanine peptidases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 39:227–231. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Couture F, Lachapelle J, Levesque RC. 1992. Phylogeny of LCR-1 and OXA-5 with class A and class D beta-lactamases. Mol Microbiol 6:1693–1705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Girlich D, Naas T, Nordmann P. 2004. Biochemical characterization of the naturally occurring oxacillinase OXA-50 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:2043–2048. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.6.2043-2048.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aravena-Román M. 2008. Cellular fatty acid-deficient Pandoraea isolated from a patient with cystic fibrosis. J Med Microbiol 57:252. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47671-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pimentel JD, MacLeod C. 2008. Misidentification of Pandoraea sputorum isolated from sputum of a patient with cystic fibrosis and review of Pandoraea species infections in transplant patients. J Clin Microbiol 46:3165–3168. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00855-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coenye T, Liu L, Vandamme P, LiPuma JJ. 2001. Identification of Pandoraea species by 16S ribosomal DNA-based PCR assays. J Clin Microbiol 39:4452–4455. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.12.4452-4455.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Segonds C, Paute S, Chabanon G. 2003. Use of amplified ribosomal DNA restriction analysis for identification of Ralstonia and Pandoraea species: interest in determination of the respiratory bacterial flora in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol 41:3415–3418. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.3415-3418.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coenye T, LiPuma JJ. 2002. Use of the gyrB gene for the identification of Pandoraea species. FEMS Microbiol Lett 208:15–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Payne GW, Vandamme P, Morgan SH, LiPuma JJ, Coenye T, Weightman AJ, Jones TH, Mahenthiralingam E. 2005. Development of a recA gene-based identification approach for the entire Burkholderia genus. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:3917–3927. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3917-3927.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poirel L, Figueiredo S, Cattoir V, Carattoli A, Nordmann P. 2008. Acinetobacter radioresistens as a silent source of carbapenem resistance for Acinetobacter spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:1252–1256. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01304-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]