LETTER

Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare are the most clinically important species of the M. avium complex (MAC). From 2009 to 2011, 277 M. avium and 229 M. intracellulare isolates considered responsible for infection based on the ATS/IDSA criteria (1) were studied (Table 1). The history of previous antibiotic treatment was prospectively noted via a standardized questionnaire mentioning whether the patient had or had not received previous treatment(s) for MAC infection. Isolates were identified using GenoType Mycobacterium CM/AS (Hain). The MICs of clarithromycin and amikacin were determined by broth microdilution assay in 7H9 medium using Sensititre Slomyco (Trek). Amplification and sequencing for rrs were performed as previously described (2) and for the target zone of rrl as previously described (3), using primers 23.1, AAT-GGC-GTA-ACG-ACT-TCT-CAA-CTG-T, and 23.2, GCA-CTA-GAG-GTT-CGT-CCG-TCC-C, with a hybridization temperature of 57°C.

TABLE 1.

Isolates included in the study stratified by history of past antibiotic treatment and results of drug susceptibility testing

| Species (total no. of isolates) | Druga | No. of isolates with indicated history of past antibiotic treatment and susceptibilityb |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not previously treated (primary resistance) |

Previously treated (secondary resistance) |

Unknown |

||||||||||||||

| Total no. | S | I | R | % R | Total no. | S | I | R | % R | Total no. | S | I | R | % R | ||

| M. avium (277) | CLR | 186 | 186 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 59 | 41 | 3 | 15 | 25 | 32 | 28 | 1 | 3 | 9 |

| AMK | 186 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 54 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 31 | 0 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| M. intracellulare (229) | CLR | 154 | 154 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45 | 41 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 30 | 29 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| AMK | 154 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

CLR, clarithromycin; AMK, amikacin.

S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant; % R, percentage of resistant isolates.

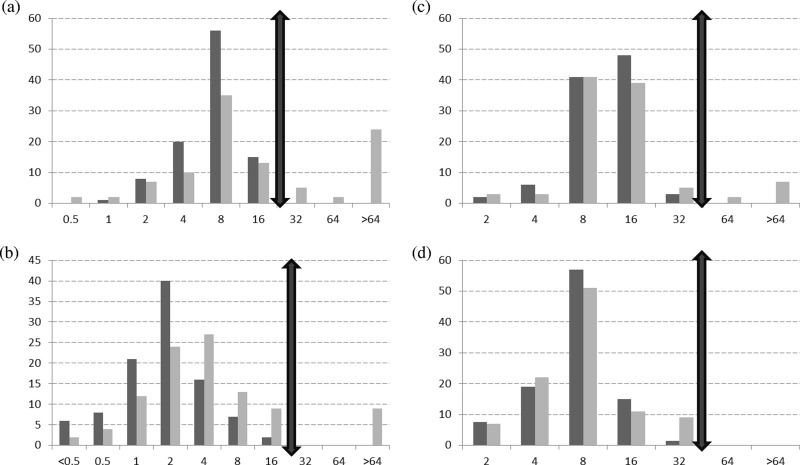

No clarithromycin-resistant isolate was found among the 186 M. avium and 154 M. intracellulare isolates from patients without previous antibiotic treatment (4). In contrast, the proportion of resistant isolates (MICs of >32 mg/liter) was 25% (15/59) for M. avium and 9% (4/45) for M. intracellulare among patients that had been treated previously (Table 1; Fig. 1). Among the 18 clarithromycin-resistant M. avium isolates (MICs of ≥64 mg/liter) obtained from patients with a history of antibiotic use or an unknown history, 12 harbored a mutation in rrl. All 5 clarithromycin-resistant M. intracellulare isolates obtained from patients with a history of antibiotic use or an unknown history had a mutation in rrl. The 4 M. avium isolates with intermediate susceptibility to clarithromycin (MIC of 32 mg/liter) and all of the susceptible isolates (MICs of ≤16 mg/liter), which were randomly selected as controls (29 M. avium and 2 M. intracellulare), had wild-type (WT) sequences. This is consistent with previous studies, which found that some isolates were resistant but had no mutation in rrl, suggesting the involvement of some other, unknown mechanism(s) (5–8). The presence of a mutation at position 2058 or 2059 indicates resistance to clarithromycin, but the absence of mutation does not prove susceptibility.

FIG 1.

Distribution of MAC isolates according to clarithromycin or amikacin MIC (mg/liter) determined by broth microdilution method. The cutoffs are symbolized by double-ended arrows. Distribution (percentage of isolates) of M. avium (a) and M. intracellulare (b) isolates according to clarithromycin MIC and of M. avium (c) and M. intracellulare (d) isolates according to amikacin MIC. Dark gray bars show data for strains isolated in patients with no history of antibiotic treatment, and light gray bars show data for strains isolated in patients with a history of antibiotic treatment.

No amikacin-resistant isolate was detected among the 186 M. avium and 154 M. intracellulare isolates from patients without previous antibiotic treatment (4). The proportion of amikacin-resistant isolates (MICs of >32 mg/liter) was 8% (5/59) for M. avium and 0% (0/45) for M. intracellulare among patients that had been treated previously (Table 1; Fig. 1). The molecular mechanism involved in amikacin resistance in MAC has recently been reported by Brown-Elliott et al. (2). In our study, the 4 isolates of M. avium with MICs of >64 mg/liter harbored a mutation of A to G at position 1408 (A1408G) in rrs, whereas the isolates with a MIC of 64 mg/liter (1 M. avium obtained from a patient with a history of previous antibiotic treatment and 1 from a patient with an unknown history) or 32 mg/liter (6 M. avium and 5 M. intracellulare isolates) had WT sequences. Interestingly, the 8 isolates with amikacin MICs of >64 mg/liter reported by Brown-Elliott et al. (2) were mainly M. intracellulare isolates (6/8), while we collected only M. avium isolates with resistance to amikacin. This point is striking since M. avium is reported to be more widely distributed than M. intracellulare in North America (9).

Our data reinforce and extend recent recommendations (10) that (i) treatment without drug susceptibility testing (DST) can be initiated based on the typical WT susceptibility profile of the species involved but that (ii) if the patient has received past antibiotic treatment, DST must be performed. In the latter case, molecular testing can be useful if DST results are doubtful or if the treatment is urgent: if a mutation is found in a target gene, the isolate is likely to be resistant, but if not, phenotypic testing remains essential.

(A part of this work was presented as an oral communication [number COL07-03] at the 15es Journées Nationales d'Infectiologie, Bordeaux, France, 12 to 13 June 2014 [11].)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

This work was indirectly supported by an annual grant from the Institut National de Veille Sanitaire to the French NRC MyRMA. The data were generated as part of our routine work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, Holland SM, Horsburgh R, Huitt G, Iademarco MF, Iseman M, Olivier K, Ruoss S, von Reyn CF, Wallace RJ Jr, Winthrop K. 2007. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175:367–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown-Elliott BA, Iakhiaeva E, Griffith DE, Woods GL, Stout JE, Wolfe CR, Turenne CY, Wallace RJ Jr. 2013. In vitro activity of amikacin against isolates of Mycobacterium avium complex with proposed MIC breakpoints and finding of a 16S rRNA gene mutation in treated isolates. J Clin Microbiol 51:3389–3394. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01612-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastian S, Veziris N, Roux AL, Brossier F, Gaillard JL, Jarlier V, Cambau E. 2011. Assessment of clarithromycin susceptibility in strains belonging to the Mycobacterium abscessus group by erm(41) and rrl sequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:775–781. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00861-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renvoise A, Bernard C, Veziris N, Galati E, Jarlier V, Robert J. 2014. Significant difference in drug susceptibility distribution between Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare. J Clin Microbiol 52:4439–4440. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02127-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamal MA, Maeda S, Nakata N, Kai M, Fukuchi K, Kashiwabara Y. 2000. Molecular basis of clarithromycin-resistance in Mycobacterium avium intracellulare complex. Tuber Lung Dis 80:1–4. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1999.0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doucet-Populaire F, Truffot-Pernot C, Grosset J, Jarlier V. 1995. Acquired resistance in Mycobacterium avium complex strains isolated from AIDS patients and beige mice during treatment with clarithromycin. J Antimicrob Chemother 36:129–136. doi: 10.1093/jac/36.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodrigues L, Sampaio D, Couto I, Machado D, Kern WV, Amaral L, Viveiros M. 2009. The role of efflux pumps in macrolide resistance in Mycobacterium avium complex. Int J Antimicrob Agents 34:529–533. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doucet-Populaire F, Buriankova K, Weiser J, Pernodet JL. 2002. Natural and acquired macrolide resistance in mycobacteria. Curr Drug Targets Infect Disord 2:355–370. doi: 10.2174/1568005023342263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoefsloot W, van Ingen J, Andrejak C, Angeby K, Bauriaud R, Bemer P, Beylis N, Boeree MJ, Cacho J, Chihota V, Chimara E, Churchyard G, Cias R, Daza R, Daley CL, Dekhuijzen PN, Domingo D, Drobniewski F, Esteban J, Fauville-Dufaux M, Folkvardsen DB, Gibbons N, Gomez-Mampaso E, Gonzalez R, Hoffmann H, Hsueh PR, Indra A, Jagielski T, Jamieson F, Jankovic M, Jong E, Keane J, Koh WJ, Lange B, Leao S, Macedo R, Mannsaker T, Marras TK, Maugein J, Milburn HJ, Mlinko T, Morcillo N, Morimoto K, Papaventsis D, Palenque E, Paez-Pena M, Piersimoni C, Polanova M, Rastogi N, Richter E, Ruiz-Serrano MJ, Silva A, da Silva MP, Simsek H, van SD, Szabo N, Thomson R, Tortola FT, Tortoli E, Totten SE, Tyrrell G, Vasankari T, Villar M, Walkiewicz R, Winthrop KL, Wagner D. 2013. The geographic diversity of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from pulmonary samples: an NTM-NET collaborative study. Eur Respir J 42:1604–1613. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00149212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CLSI. 2011. Susceptibility testing of Mycobacteria, Nocardiae, and other aerobic Actinomycetes. CLSI document M240A2. Approved standard, 2nd ed CLSI, Wayne, PA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renvoisé A, Brossier F, Veziris N, Galati E, Jarlier V, Bernard C. 2014. COL07-03: La résistance primaire existe-t-elle dans les infections à mycobactéries non tuberculeuses à croissance lente? Med Mal Infect 44(Suppl):13. doi: 10.1016/S0399-077X(14)70071-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]