Abstract

Background:

Off-loading of the ulcer area is extremely important for the healing of plantar ulcers. Off-loading with total contact cast (TCC) may be superior to other off-loading strategies studied so far, but practical limitations can dissuade clinicians from using this modality. This study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of TCC compared with that of a pressure-relieving ankle foot orthosis (PRAFO) in healing of diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers and their effect on gait parameters.

Methods:

Thirty adult diabetic patients attending the foot clinic with neuropathic plantar ulcers irrespective of sex, age, duration and type of diabetes were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 off-loading modalities (TCC and PRAFO). Main outcome measures were ulcer healing after 4 weeks of randomization and effect of each of the modalities on various gait parameters.

Results:

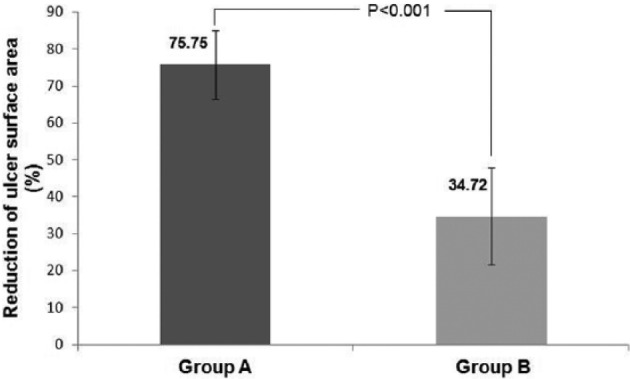

The percentage reduction of the ulcer surface area at 4 weeks from baseline was 75.75 ± 9.25 with TCC and 34.72 ± 13.07 with PRAFO, which was significantly different (P < .001). The results of this study however, showed that most of the gait parameters were better with PRAFO than with TCC.

Conclusions:

This study comprehensively evaluated the well known advantages and disadvantages of a removable (PRAFO) and a nonremovable device (TCC) in the treatment of diabetic neuropathic foot ulcer. Further studies are needed involving larger subjects and using 3D gait analysis to collect more accurate data on gait parameters and wound healing with different off-loading devices.

Keywords: diabetes, neuropathy, foot ulcer, off-loading, TCC, PRAFO

Diabetes mellitus is a disease known for its multifaceted complications, and foot ulceration is one of the most devastating complications carrying significant socioeconomic impact.1 It has been found that 40-70% of all nontraumatic amputations of the lower limbs occur in patients with diabetes.2,3 Furthermore, many studies have reported that foot ulcers precede approximately 85% of all amputations performed in diabetic patients.3 Lower extremity amputations are at least 10 times more common in people with diabetes than in nondiabetic individuals in developed countries.4

Out of all nontraumatic lower limb amputations, 50% occur in diabetics, mostly as a result of foot ulcers.1 The prevalence of foot ulcers ranges from 4% to 10% among persons diagnosed with diabetes mellitus; the condition is more frequent in older patients.2,5 It is estimated that about 5% of all patients with diabetes present with a history of foot ulceration, while the lifetime risk of diabetic patients developing this complication is 15%.6,7 Diabetics in India are more prone to develop neuropathic foot ulcers because of the prevalent habit of barefoot walking. A major biomechanical factor in the causation of foot ulcers in persons with diabetes is elevated peak plantar pressure. Offloading the ulcer area in the form of equalization of pressure across the plantar surface of the foot can accelerate healing of the ulcer.

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy affects up to 50% of older type 2 diabetic patients.8,9 Often, the first sign of peripheral neuropathy is a neuropathic ulcer. Other patients have neuropathic pain and on examination are found to have severe loss of sensation. This combination is described as “painful-painless legs,” and these patients are at increased risk for foot ulceration. With sufficient vascular supply, appropriate debridement, moist wound environment, and infection control, the primary mode of healing a diabetic neuropathic foot ulcer is pressure dispersion.10 Of the plethora of offloading modalities including wheel chairs, crutches, felted foam, half shoes, therapeutic shoes, total contact casts (TCC), custom splints, and removable cast walkers, nonremovable TCC is considered by many to be the “gold standard” in achieving pressure redistribution.11 Off-loading with TCC may be superior to other off-loading strategies studied so far, but practical limitations can dissuade clinicians from using this modality. Pressure-relieving ankle foot orthosis (PRAFO) is an orthosis used in offloading diabetic ulcer provides ankle motion as well. It allows daily wound care, and ambulation is less impaired than with a cast.

The authors conducted a clinical trial to investigate wound healing in diabetes patients with plantar ulcers who were randomized for treatment with either TCC or PRAFO.

Methods

Subject Recruitment

This prospective study was conducted from January 2012 to December 2013 in a tertiary care center in India. Diabetic patients attending the foot clinic with plantar ulcer irrespective of sex, age, duration, and type of diabetes were considered for the study. The study was approved by hospital ethics committee and the participants were provided with a written information sheet explaining the study and asked to sign consent forms. To be eligible for the study, participants should be ambulatory, have solitary neuropathic plantar ulcer grade 1A or 2A using the University of Texas scale, and unilateral foot involvement. The grade was based on clinical examination and evaluation of a plain digital radiograph. Patients unable to walk indoors, with significant comorbidities, infected ulcers and/or osteomyelitis, ankle brachial index (ABI) < 0.9, and Charcot osteoarthropathy were excluded.

Protocol

Patients were randomly allocated to 1 of 2 off-loading procedures using the randomization table: TCC or PRAFO. All patients received the same educational guidelines on foot care and general information on the importance of appropriate footwear. All patients attended the foot clinic weekly for device inspection. Wound care and wound debridement was carried out by a single podiatrist blinded to treatment mode. Tissue bits from the base of the wound was collected, sent for culture (aerobic and anaerobic) and antibiotics were dispensed if necessary before application of TCC or PRAFO. Data were collected at baseline and outcomes assessed in all patients at 2 and 4 weeks. Two outcome measures were used. The primary outcome measure was percentage reduction in the surface area of ulcer after 4 weeks. The secondary outcome measure was to document which of the device was associated with comparatively better and acceptable gait parameters at 2 weeks. The different parameters were also defined: walking velocity means time taken to walk a known distance; cadence means number of steps taken during a known period of time; step length (in cm) is the distance from heel center of the current footprint to the same of the next footprint of the opposite foot; stride length (in cm) is the distance from heel strike of one extremity to the heel strike of same extremity again in the next step. All the gait parameters were measured by asking the patients to walk with their device.

Demographic data such as sex, age, height, and weight were collected from the subjects. All of them were screened with monofilament (10 g) and biothesiometer for evidence of neuropathy and ABPI was calculated with the handheld Doppler. All necrotic tissues at the base and margins of the ulcers were carefully removed by a scalpel. The outline of the wound was then drawn on a transparent sheet of paper, which was then transferred to a graph paper. The area of the wound was then calculated by counting the number of squares in the graph paper and was expressed as cm2. Photographs were taken of each ulcer.

TCC

TCC was done by plaster of Paris (POP) cast and a simple rubber insole was incorporated between the sole of the patient and the POP cast (Figure 1). Before incorporating the insole, the area of the insole overlying the ulcer was removed from its plantar aspect (that is from that part of insole, which is in contact with the POP cast) to avoid pressure on the ulcer. The cast was allowed to dry and it became irremovable. The patients were asked to come after 2 weeks. The gait parameters were taken and the TCC was removed. The limb was inspected, the wound was cleaned with normal saline, and a new TCC was put on for another 2 weeks.

Figure 1.

Total contact cast (TCC) applied on a patient.

PRAFO

Preparation of PRAFO was a bit complicated. At first cast was taken by maintaining the ankle at neutral position. Once the cast was set, it was removed from the extremity and filled with liquid POP. At that time modifications were done to get proper clearance of malleoli to avoid pressure over the malleoli. Further adjustments were made to keep the toe in hyperextension (for getting the toe rocker), keep the ankle at 90 degrees and make the arch in proper shape. A build-up of 3 mm thickness was made around the ulcerate area to offload the ulcer. Ankle joints were incorporated to provide ankle motion. Pelite sheet was molded over the planter aspect of the foot and a 3 mm polypropylene sheet was draped over the modified mold. Once it was completely set, it was gently removed with the necessary trim lines. Velcro closures were provided and the required trials were carried out over the patient. After the required trials, the brace was well padded off (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Off-loading method used in pressure-relieving ankle foot orthosis (PRAFO).

Follow-Up

Subjects in group A continued with TCC while those of group B were provided with PRAFO. All of the patients of group B were repeatedly asked to use the PRAFO along with their normal routine activities as much as possible. They were also asked to use the PRAFO while taking a shower, using the bathroom and while on bed to avoid any possible pressure on the ulcer area. The above advice was superfluous to group A as TCC was irremovable. After 2 weeks they were called for follow-up, and the following parameters were noted on 10 m walkway after making them familiar with the procedure: step length; stride length, cadence, walking velocity. They were asked to continue the same orthosis for another 2 weeks and at the end of it the TCCs were removed and ulcer area measurements were taken again in both the groups. Before measuring the gait parameters, the patients were asked to wear socks over their orthosis following which ink is applied to sole and impression of foot prints were taken on a paper walkway.

Statistical Analysis

The collected data were managed on an Excel spreadsheet and was analyzed using GraphPad Prism for windows (Version 6.01, GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± SD. Homogeneity of the initial distribution of baseline primary variables between groups was tested using unpaired t test for continuous variables. All posttreatment parameters like differences in ulcer size reduction and gait parameters between the 2 groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney test. The P value of < .05 was considered significant.

Results

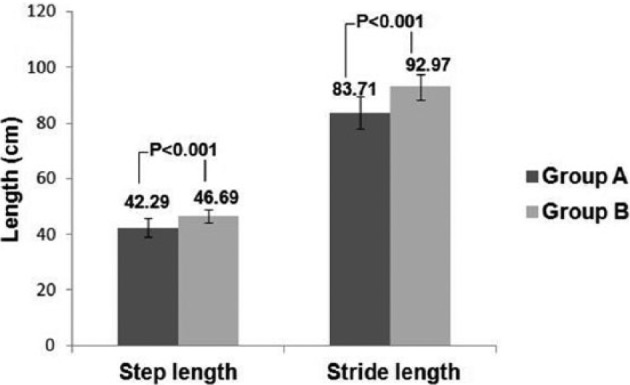

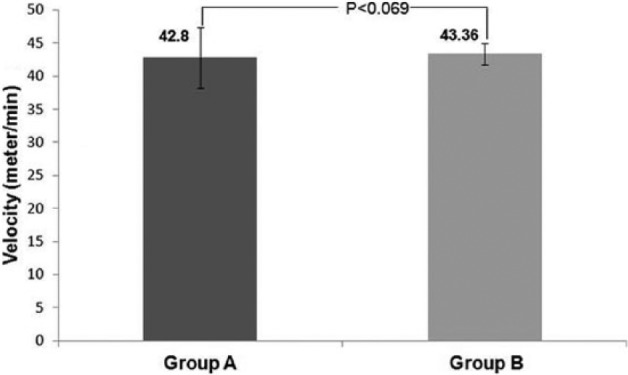

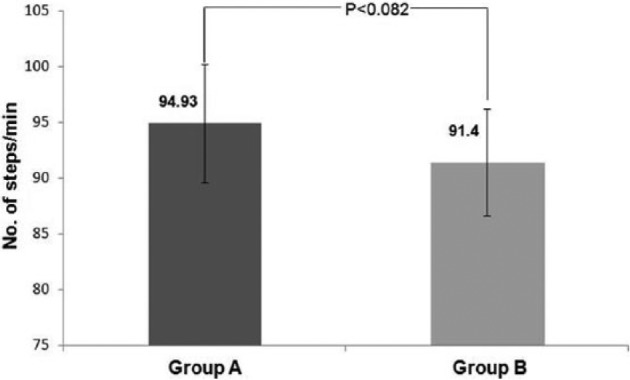

The mean age, duration of diabetes, BMI, and glycemic status of the patients at study entry were statistically insignificant between the 2 groups. The mean surface areas of the plantar ulcers between the groups were also not significant at the baseline (Table 1). The mean step length and stride length was significantly lower in patients with TCC compared to patients with PRAFO (Figure 3), and as a result, the mean value of the cadence was higher with TCC than with PRAFO (Figure 4). The walking velocity, though higher with PRAFO, was not statistically significant. However, the difference in walking velocity almost reached significance (Figure 5). As a whole, the results of this study showed that most of the gait parameters were significantly better with PRAFO than with TCC as the subjects walked significantly faster using the PRAFO as compared to TCC.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients in 2 Groups.

| Parameter | TCC group (n = 15) | PRAFO group (n = 15) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 51.40 ± 12.84 | 53.00 ± 13.19 | .739 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | 8.87 ± 3.87 | 8.47 ± 4.85 | .805 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.70 ± 4.34 | 23.51 ± 4.18 | .605 |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.21 ± 1.08 | 8.09 ± 1.16 | .771 |

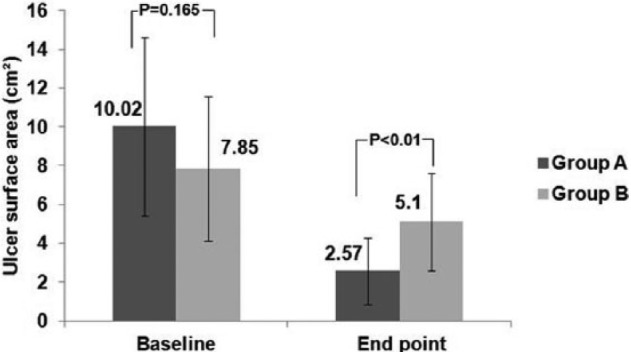

| Ulcer surface area (cm2) | 10.02 ± 4.58 | 7.85 ± 3.70 | .165 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD. P < .05: statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Comparison of step length and stride length between 2 groups

Figure 4.

Comparison of cadence (steps/min) between 2 groups

Figure 5.

Comparison of walking velocity (meter/min) between 2 groups

The figures were much impressive when we looked at the parameters of ulcer healing. At the beginning of the study, the mean surface areas of the planter ulcers were 10.02 cm2 and 7.85 cm2 in groups A (TCC) and B (PRAFO), respectively. At the end of the study, it became 2.57 cm2 in group A and 5.1 cm2 in group B (Figure 6). The percentage reduction of the ulcer surface area at 4 weeks from baseline was 75.75 ± 9.25 with TCC and 34.72 ± 13.07 with PRAFO, which was significantly different (P < .001) (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Change in ulcer surface area from baseline to end point.

Figure 7.

Reduction of ulcer surface area between 2 groups.

Discussion

Foot ulceration is a major consequence of diabetes, and is thought to affect 15% of all people with diabetes at some time during their lives.12 Peripheral neuropathy affects approximately 30 to 50% of people with diabetes and neuropathic ulceration remains the commonest type of foot ulcer in them. Neuropathy produces changes that include sensory, motor and autonomic components, all of which will impact on the diabetic foot. Decreased pain sensation and muscular spatial awareness due to neuropathy lead to abnormal loading of the foot, which in turn leads to increased pressure on the sole (plantar aspects) of the foot.13 Estimates of the prevalence of plantar wounds range from 25-35% of the first toe through 23-50% of the first metatarsophalangeal joint to 38% for the lesser metatarsal heads.11,14 People with diabetes are 15 to 40 times more likely to undergo an amputation compared to the rest of the population, and this rate is at least 50% higher in men than women.15

Mechanical protection of the foot is essential for healing; consideration must be paid to either “unweighting” the foot (that is, no weight on the foot or wound) or “off-loading” (that is, rebalancing the weight on the foot/leg, with the patient still weight-bearing). The term pressure redistribution was introduced to improve the terminology used to describe the mechanical attempts clinicians make to reduce working forces on the site of ulceration. Off-loading of the ulcer area is extremely important for the healing of plantar ulcers. Retrospective and prospective studies have shown that elevated plantar pressures significantly contribute to the development of plantar ulcers in diabetic patients.16,17 In addition, any existing foot deformities may increase the possibility of ulceration, especially in the presence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy and inadequate off-loading. Furthermore, inadequate off-loading of the ulcer has been proven to be a significant reason for the delay of ulcer healing even in an adequately perfused limb.18 The proper and scientific application of different pressure-relieving devices to reduce pressure on plantar wounds, improve gait, and allow activities of daily life goes far beyond simple insole and footwear modifications. McGuire in 2010 described most clinicians as compassionate individuals who want their patients to get better. At the same time, they feel bad about putting their patients in nonremovable devices or devices that are particularly restrictive. On the other hand, before prescribing a removable device, they should be aware of the fact that the patients may not be adherent and will probably remove the device, walk barefoot in the home, and may use standard footwear when they go out in public. Consequently, they may have less tissue protection than the actual needs, which eventually delay the wound healing, the main goal of the prescribed device.19

TCC, by providing a larger surface area to distribute weight-bearing forces, allows better wound healing and at the same time limits joint motion distal to the knee and alters normal gait parameters such as cadence and stride length. TCC has proven to be very effective in promoting healing, with complete ulcer healing in as short as 1 to 2 months. Previous studies have shown the superiority of TCC over conventional dressing in the management of diabetic foot ulcers.20 It has also been shown that there was a significant reduction in the number of steps taken with the TCC and the restrictive quality of the TCC led to less activity, less weight-bearing, and consequent good wound healing. However, the application of TCC is time consuming and often associated with a learning curve. Most centers do not have a physician or cast technician available with adequate training or experience to safely apply a TCC; improper cast application can cause skin irritation and in some cases even frank ulceration. In addition TCCs do not allow daily assessment of the foot or wound and are therefore often contraindicated in cases of soft tissue or bone infections.

One of the ways of ulcer treatment involves the use of PRAFO, which also reduces pressure and shear forces on the sole of the foot and protects the foot from repetitive injury. PRAFO also allows patients to remain ambulatory throughout the ulcer healing period. In addition to that patients, quite often are able to maintain their daily activities and employment status. In addition, PRAFO requires little participation of the patient or the family members and allows daily wound care. Like other removable devices, PRAFO requires active patient participation and adequate compliance for satisfactory wound healing. Because it is removable, the patient and physician can monitor the foot continuously and the areas of redness can be treated before skin breakdown occurs.

The important determinants of satisfactory ulcer healing are adequate off-loading along with glycemic status, presence/absence of infection, vascularity, age of the patient, duration of diabetes and size of the wound. Infection was ruled out meticulously in each of the 30 patients before putting them on TCC or PRAFO. There was no difference in between the 2 groups as far as the age of patients, duration of diabetes, glycemic status, vascularity of the limb and size of the ulcers at baseline are concerned. Satisfactory glycemic status was ensured in each of them during the entire study period as well. In our study the ulcer healing rate was much better with TCC than PRAFO which is likely to be the result of poor patient compliance and less time spent on the device while at home. A study from the west has also shown that patients spend a significant time without device when they were given a removable cast walker.21 However, Faglia et al reported comparative efficacy of removable and fixed devices in the ulcer healing rate in their study population.22

Off-loading devices are known to enhance the somatosensory feedback from sensate skin, thereby positively affecting gait parameters in diabetic peripheral neuropathy.23 To overcome the drawbacks of TCC, a number of devices have been formulated to mobilize the ankle and thus allow a better gait compared to TCC.24 Going by the same principle, we tried PRAFO in a subset of our patient population. About 60% patients on PRAFO satisfactorily performed their activities of daily life with satisfaction in addition to the improvement in level walking and all the patients found it easy to apply. The patient satisfaction was determined by using simple questionnaires, which were provided to them during the study. However, we did not look into this particular aspect in detail because the questionnaires were not adequately validated and patient satisfaction was not among the outcome measures of this particular study. We also noticed statistically significant difference in favor of improved gait parameters such as stride length, step length, and velocity with the PRAFO.

Last but not the least, cost is a major limiting issue in the health care system of the developing countries like India. Total cost of materials for making a single TCC was INR 1623 (US$27). As the patients on group A were put on TCC twice during the study, the cost per patient in group A was INR 3264 (US$53). The cost of the raw materials for making 1 unit of PRAFO was INR 5800 (US$95), significantly higher than TCC. For this reason, in a resource restricted settings TCC is definitely a better alternative than PRAFO in the treatment of neuropathic ulcers.

Study Limitations

Our study comprehensively evaluated the well known advantages and disadvantages of a removable (PRAFO) and a nonremovable device (TCC) in the treatment of diabetic neuropathic foot ulcer. Moreover, the results indicated that the PRAFO might be a useful therapeutic tool in improving gait parameters, social acceptability and also in ulcer healing if patient is motivated and compliant to the suggestions of the care givers. However, this study has several drawbacks. The sample size was small and follow-up, for practical purposes, was relatively short (not done until complete ulcer healing). We have used simple paper walkway for gait parameters. Using 3D gait analysis would have been more accurate to study the gait parameters.

Conclusions

Healing of the wound should be the primary goal of any treatment directing toward diabetic foot ulcers. We strongly believe that education and compliance is a major issue in our patient population with a habit of barefoot walking. Based on the data from our study, TCC scores far better than PRAFO as per healing of the wound is concerned. Although it alters gait parameters in a somewhat unfavorable way, this can be acceptable considering the higher rate of wound healing with TCC. Moreover, the cost of treatment for PRAFO was almost double than that of TCC in our study. Therefore, it may be recommended from these findings that TCC should be used as the standard treatment for diabetic neuropathic plantar foot ulcers and other off-loading devices may be considered in whom TCC is contraindicated or the expertise of TCC application and removal is not available. Further studies are needed involving larger subjects and using 3D gait analysis to collect more accurate data on gait parameters and wound healing with different off-loading devices.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ABI, ankle brachial index; BMI, body mass index; PRAFO, pressure-relieving ankle foot orthosis; TCC, total contact cast.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Dang CN, Boulton AJ. Changing perspectives in diabetic foot ulcer management. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2003;2:4-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lauterbach S, Kostev K, Kohlmann T. Prevalence of diabetic foot syndrome and its risk factors in the UK. J Wound Care. 2010;19:333-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moxey PW, Gogalniceanu P, Hinchliffe RJ, Loftus IM, Jones KJ, Thompson MM, Holt PJ. Lower extremity amputations—a review of global variability in incidence. Diabet Med. 2011;28:1144-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Icks A, Haastert B, Trautner C, Giani G, Glaeske G, Hoffmann F. Incidence of lower-limb amputations in the diabetic compared to the non-diabetic population. Findings from nationwide insurance data, Germany, 2005-2007. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2009;117:500-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Preventing foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. JAMA. 2005;293:217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abbott CA, Carrington AL, Ashe H, et al. The North-West Diabetes Foot Care Study: incidence of, and risk factors for, new diabetic foot ulceration in a community-based patient cohort. Diabet Med. 2002;19:377-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Katsilambros N, Dounis E, Makrilakis K, Tentolouris N, Tsapogas P. Atlas of the Diabetic Foot. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Young MJ, Boulton AJM, McLeod AF, Williams DRR, Sonksen PH. A multicentre study of the prevalence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the UK hospital clinic population. Diabetologia. 1993;36:150-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kumar S, Ashe HC, Parnell LN, et al. The prevalence of foot ulceration and its correlates in type 2 diabetes: a population-based study. Diabetic Med. 1994;11:480-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wu SC, Crews RT, Armstrong DG. The pivotal role of offloading in the management of neuropathic foot ulceration. Curr Diab Rep. 2005;5:423-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Walker SC. Healing rates of diabetic foot ulcers associated with midfoot fracture due to Charcot’s arthropathy. Diabetic Medicine. 1997;14:46-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reiber GE. Epidemiology of foot ulcers and amputations in the diabetic foot. In: Bowker JH, Pfeifer MA, eds. The Diabetic Foot. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2001:13-32. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boulton A. The pathogenesis of diabetic foot problems: an overview. Diabetic Medicine. 1996;13(supp 1):S12-S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stess R, Jensen J, Mirmiran R. The role of plantar pressures in diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 1997; 20:855-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data and Trends: National Diabetes Surveillance System. Atlanta, GA: National Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frykberg RG, Lavery LA, Pham H, Harvey C, Harkless L, Veves A. Role of neuropathy and high foot pressures in diabetic foot ulceration. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1714-1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pham H, Armstrong DG, Harvey C, Harkless LB, Giurini JM, Veves A. Screening techniques to identify people at high risk for diabetic foot ulceration: a prospective multicenter trial. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:606-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lebrun E, Tomic-Canic M, Kirsner RS. The role of surgical debridement in healing of diabetic foot ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2010;18:433-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McGuire J. Transitional off-loading: an evidence-based approach to pressure redistribution in the diabetic foot. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2010;23:175-188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ganguly S, Chakraborty K, Mandal PK, et al. A comparative study between total contact casting and conventional dressings in the non-surgical management of diabetic plantar foot ulcers. J Indian Med Assoc. 2008;106: 237-239, 244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Kimbriel HR, Nixon BP, Boulton AJ. Activity patterns of patients with diabetic foot ulceration: patients with active ulceration may not adhere to a standard pressure off-loading regimen. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2595-2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Faglia E, Caravaggi C, Clerici G, et al. Effectiveness of removable walker cast versus non-removable fiberglass off-bearing cast in the healing of diabetic plantar foot ulcer: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1419-1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grewal GS, Bharara M, Menzies R, Talal TK, Armstrong D, Najafi B. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy and gait: does footwear modify this association? J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2013;7:1138-1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hissink RJ, Manning HA, van Baal JG. The MABAL shoe, an alternative method in contact casting for the treatment of neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:320-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]