Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is currently the third leading cause of death in the US and is associated with an abnormal inflammatory response to cigarette smoke (CS). Exposure to CS induces oxidative stress and can result in cellular senescence in the lung. Cellular senescence can then lead to decreased proliferation of epithelial cells, the destruction of alveolar structure and pulmonary emphysema. The anti-aging gene, klotho, encodes a membrane bound protein that has been shown to be a key regulator of oxidative stress and cellular senescence. In this study the role of Klotho (KL) in oxidative stress and cellular senescence was investigated in human pulmonary epithelial cells exposed to cigarette smoke. Individual clones that stably overexpress Klotho were generated through retroviral transfection and geneticin selection. Klotho overexpression was confirmed through RT-qPCR, Western blotting and ELISA. Compared to control cells, constitutive Klotho overexpression resulted in decreased sensitivity to cigarette smoke induced cell death in vitro via a reduction of reactive oxygen species and a decrease in the expression of p21. Our results suggest that increasing Klotho level in pulmonary epithelial cells may be a promising strategy to reduce cellular senescence and mitigate the risk for the development of COPD.

Keywords: Cigarette smoke, Klotho, Oxidative stress, COPD, epithelial cells, aging

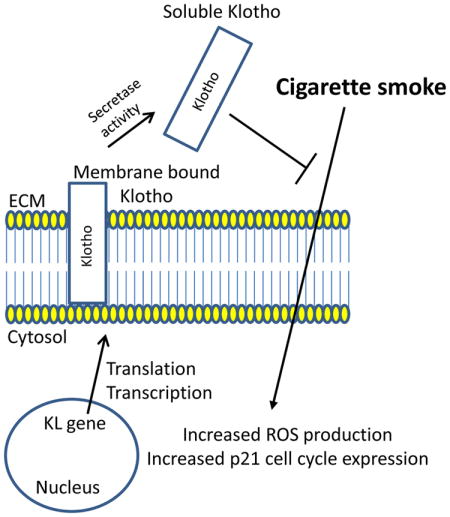

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is currently the third leading cause of death in the United States1–3, and the number of COPD cases continue to increase2, 4. COPD is characterized by increased pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis that leads to irreversible airflow limitation in the lung5, 6. The primary causes of COPD are pulmonary emphysema and chronic bronchitis due cigarette smoke (CS)7. Exposure to cigarette smoke induces oxidative stress in the lung8, 9 initiating cellular senescence or aging. Oxidative stress promotes epithelial cell death and the enlargement of alveolar structures resulting in emphysema, reduced airflow and difficulty breathing10.

Physiological lung aging is associated with several anatomic (enlargement of alveoli) and functional changes (reduced airflow) that result in a progressive decrease in expiratory flow rates over time11. Although aging is a natural process, cellular senescence of pulmonary epithelial cells increases dramatically after exposure to cigarette smoke12–14. Therefore, it is not surprising that COPD manifests itself in older adults (greater than 45 years of age)2. Abnormal regulation of the mechanisms involved in aging (including cellular senescence, oxidative stress, and changes in the expression of anti-aging molecules) may contribute to the pathogenesis of COPD15. Because cellular senescence is directly correlated with aging, and exposure to cigarette smoke accelerates lung aging, therapies that significantly reduce or inhibit cellular senescence may be important in the overall treatment of this disease16.

The anti-aging gene, klotho, codes for a single-pass transmembrane protein, classified as α-Klotho (KL), which is expressed primarily in the kidney17. Klotho knockout mice display a syndrome that resembles human aging and includes a shorter lifespan and premature emphysema17. Conversely, overexpression of Klotho in mice extends lifespan and indicates that the klotho gene functions as an aging or senescence suppressor gene18. At the cellular level, Klotho exists as a membrane bound protein that is composed of a large extracellular domain that can be cleaved and released as a soluble protein, and is detectable in cerebrospinal fluid and blood19. Membrane bound KL functions as a co-receptor for fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23)20, whereas secreted KL functions as a hormonal factor independent of FGF23. Secreted KL has been shown to regulate the activity of growth factors such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), Wnt, and transforming growth factor. (TGF)-β118, 21, 22, and can activate the TRPV5 ion channel22–24. Moreover, KL has been shown to be involved in the regulation of oxidative stress by activating the FOXO forkhead transcription factor, which increases the expression of manganese superoxide dismutase25, 26. Because soluble Klotho has been shown to inhibit multiple pathways involved in aging, such as insulin signaling and oxidative stress, augmenting Klotho or its effects may counteract problems resulting from aging.

Previous studies have demonstrated that α-Klotho can protect against oxidative stress both in vitro as well as in vivo27–29. Overexpression of KL confers resistance to oxidative stress and apoptosis induced by oxidants25, 30. Although increased oxidative stress due to uremia accelerates cellular senescence in endothelial cells leading to decreased expression of intracellular KL, exogenous KL has been shown to prevent cellular senescence by inhibiting oxidative stress and diminishing nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) binding 27. Pulmonary epithelial cells, transfected with α-Klotho, are protected from oxidative damage due to hyperoxia and phosphotoxia by increasing the antioxidant levels in cells via the Nrf2 pathway28. COPD is correlated with increased cellular senescence and oxidative stress of pulmonary epilthelia12, 14, 31–33. Moreover, heightened oxidative stress may contribute to premature alveolar damage and the development of emphysema. Therefore, we hypothesized that overexpression of KL may be a novel therapy to combat CS-induced senescence by increasing the antioxidant capacity to enable epithelial cells to be protected against such injury. To this end, human epithelial cells were stably transfected with the KL open reading frame and exposed to cigarette smoke in order to determine whether overexpressing KL protected against CS-induced cell death.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and Reagents

BEAS-2B cells (human lung epithelial cell line) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator in complete media containing Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The pCMV-Entry Vectors with and without the Klotho open reading frame were obtained from OriGene Technologies (Rockville, MD). Lipofectamine ® 2000 and human Klotho, Actin, p21 and p27 primer and probe sets were obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Cloning cylinders were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Cigarette smoke extract (CSE) (dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO], 40 mg/ml total particulate matter, nicotine content of 6%; kept at −80°C) was purchased from Murty Pharmaceuticals (Lexington, KY) and diluted in cell culture media immediately before use.

Stable Transfections and Selection of Clones

Klotho is known to be expressed at very low levels in pulmonary epithelial cells28 and low expression of KL was confirmed in the human epithelial cell line (BEAS-2B) used in this study. BEAS-2B cells were plated in 10% FBS without antibiotics. Cells were transfected the next day according to the manufacturer’s instructions with 2500 ng of a lentiviral plasmid that contained the full length ORF (including the transmembrane domain) of human the KL gene. BEAS-2B cells were also transfected with the lentiviral plasmid without the KL ORF. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were passed at 1:20 into fresh growth medium containing G418 (1 mg/ml) for selection. Individual clones (P1) were selected 14 days after the addition of G418. Expression levels of all clones selected were determined through RT-qPCR (Supplemental Figure 1). Cells transfected with the empty vector, which had comparable KL expression levels compared to normal BEAS-2B cells, were chosen as the empty vector control cells (Clone 5). Cells transfected with the KL ORF, which had the highest KL expression levels were chosen as the KL-overexpressing cells (Clone 4). All experiments were completed using early passage cells (P2 – P13) and overexpression of Klotho in multiple passages was confirmed through RT-qPCR and ELISA.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated using the Rneasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Reverse transcription of RNA was performed using the Multiscribe RT Kit (Life Technologies). Gene expression was measured using assays on demand probe sets (Applied Biosystems), and reactions were analyzed using the ABI One Step real-time PCR system. Actin was used for normalization. To determine the effects of CS on human epithelial cells, cells were exposed to 200 μg/ml CSE for 24 hours, RNA was isolated and expression levels of p21 and p27 were quantified. More than three independent biological replicates were performed for the quantification of KL mRNA levels and three biological replicates were performed for the cell cycle analysis using three technical replicates for each experiment (n = 3). Relative fold change was calculated by using the following formulas: ΔCT = CT (target gene)–CT (Actin) and FC = 2−(ΔCT2−ΔCT1), in which ΔCT1 represents the highest CT value among DMSO treated control samples and ΔCT2 represents the value of a particular sample as previously described34.

Immunoblot analysis

Cell extracts were isolated using RIPA buffer followed by sonication. 15 μg of protein were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Immunoblots were probed with an anti-human Klotho rabbit polyclonal antibody. The blots were probed with an HRP goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated secondary and binding was visualized through chemiluminescence. Immunoblots were then stripped and reprobed with an anti-human Actin rabbit polyclonals antibody. Two independent biological replicates were performed for membrane bound KL using three technical replicates for each experiment (n = 3).

Cytotoxicity analysis

KL-overexpressing cells and control cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of cigarette smoke extract (CSE) (200–700 μg/ml) for 24 hours. Cell viability was assessed 24 hours after CSE exposure through the CellTiter Blue Cell Viability Assay as suggested by the manufacturer (Promega, Madison, WI). Fluorescence (560EX/590EM) was acquired using the Infinite® M200 Microplate reader (Tecan, San Jose, CA, USA). Three independent biological replicates were performed for the cytotoxicity assays using ten technical replicates for each experiment (n = 10).

ELISA

Cell culture supernatants were removed 24 hours after exposure to either 200 μg/ml CSE and/or 200 ng/ml LPS exposure. Commercially available ELISA kits were used to quantify the levels of either human α-Klotho (IBL America, Minneapolis, MN), or IL-8 and IL-6 (Affymetrix, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. More than three independent biological replicates were performed during the course of the study for the quantification of α-Klotho using 3 technical replicates for each experiment (n = 3). Two independent biological replicates were performed for the quantification of IL-8 and IL-6 using 3 technical replicates for each experiment (n = 3).

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Glutathione (GSH) Quantification

ROS levels were quantified in cells, 3 hours after exposure to CSE (200 μg/ml) or H2O2 (50 mM) through the ROS-Glo Assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). GSH levels were quantified in cells, 6 hours after exposure to CSE (200 μg/ml) or buthionine sulphoximine (BSO) (200 μM) through the GSH-Glo Assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). Luminescence was acquired using the Infinite® M200 Microplate reader (Tecan, San Jose, CA, USA). Relative fold changes (FC) in ROS levels were calculated using the following equation; FC = luminescence of sample (treated with DMSO, CSE or H2O2)/luminescence of control sample (treated with DMSO only). Three independent biological replicates were performed for the ROS and GSH quantifications using five to ten technical replicates for each experiment (n = 5–10).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Analyses were done using the software package GraphPad Prism 6.0 (San Diego, CA). One or two-way ANOVAs were used to compare groups with one or two independent variables, respectively. All data from the biological replicates were used to determine differences among groups. Significance was noted at P < 0.05.

Results

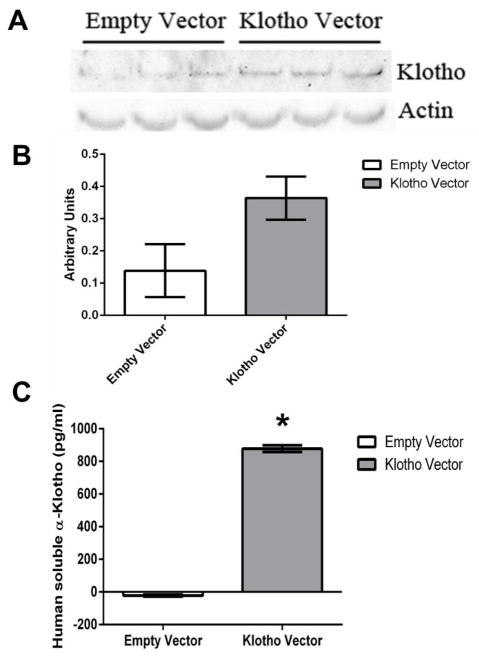

In order to confirm that the stable transfection produced cells that were able to express high levels of the KL protein, an immunoblot analysis was performed to quantify membrane bound KL. KL-overexpressing cells expressed increased levels of membrane bound KL. Increased levels of KL were not statistically different compared to control cells. However, KL-overexpressing cells expressed and secreted significantly higher levels of soluble KL in the cell culture supernatant than control cells (P < 0.05) (Figure 1). These data indicate that the increased protein expression of KL was successful and that the soluble KL form was significantly increased in cell culture supernatant compared to control cells.

Figure 1.

Increased membrane bound and soluble Klotho production in stably transfected human epithelial cells. A) Representative western blot of membrane bound Klotho expression in human epithelial cells. Expression of Actin was used as a loading control. B) Densitometry analysis of the membrane bound Klotho protein normalized to Actin expression for the experiment shown in A. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). C) Representative enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) results for extracellular soluble Klotho. Data presented in B) and C) are mean ± SEM of one biological replicate (n = 3). Asterisks indicate a significant difference between control cells and Klotho overexpressing cells (P < 0.05).

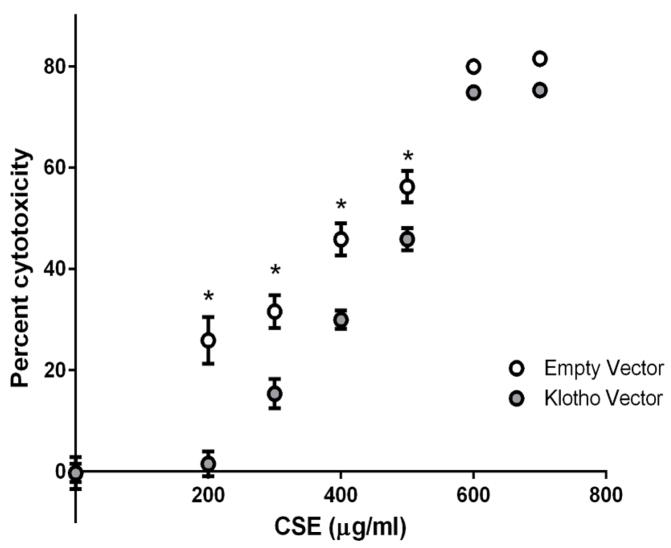

We next examined whether extracellular KL expression could moderate cytotoxicity due to CS exposure. Cytotoxicity was quantified 24 hours after cells were exposed to 200–700 μg/ml CSE. KL-overexpressing cells were significantly protected from CSE-induced cell death between 200 and 500 μg/ml CSE compared to control cells (P < 0.05) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overexpression of Klotho in stably transfected human epithelial cells protects against cytotoxicity due to cigarette smoke extract (CSE). Cells were exposed to 200 μg/ml of CSE for 24 h and cytotoxicity was quantified using the CellTiter Blue assay. Data presented are mean percent cytotoxicity ± SEM of three biological replicates (n = 10 for each experiment). Asterisks indicate a significant difference between control cells and Klotho overexpressing cells exposed to CSE (P < 0.05).

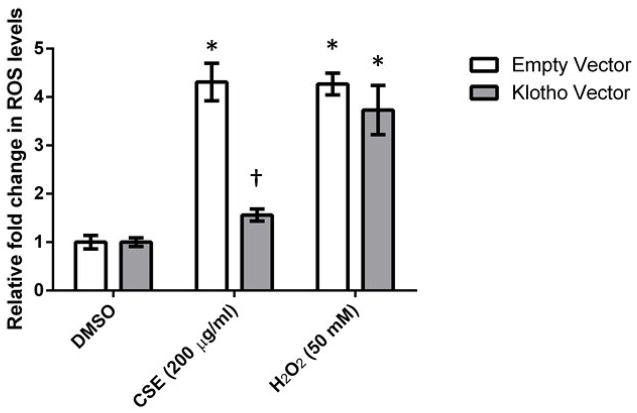

CS is known to contain greater than 1014 free radicals per puff and oxidative damage from CS exposure leads to cell death35. In the presence of both CSE and H2O2 (positive control), empty vector control cells produced significantly higher levels of ROS (P < 0.05) (4.3 fold increase in fluorescence). KL-overexpressing cells also produced a similar significant increase with H2O2 (P < 0.05) (3.73 fold increase in fluorescence). However, the increase observed in the presence of CSE was blunted in KL-overexpressing cells, and was significantly different compared to control cells treated with CSE (Figure 3). No significant differences were observed in glutathione (GSH) levels between KL-overexpressing cells and controls cells after 6 hours of CSE exposure (Supplemental Figure 2). These data indicate that extracellular KL is able to protect cells from CSE-induced cytotoxicity by reducing intracellular ROS levels.

Figure 3.

Soluble extracellular Klotho decreases reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in human epithelial cells after exposure to CSE. Control cells and KL-overexpressing cells were exposed to 200 μg/ml of CSE for 3 h, and ROS levels were quantified using the ROS Glo assay. Data presented are mean relative fold change ± SEM of three biological replicates (n = 10 for each experiment). Asterisks indicate a significant difference between mock treated cells and cells exposed to CSE (P < 0.05). Dagger indicates a significant difference between empty vector control cells and KL-overexpressing cells exposed to CSE (P < 0.05).

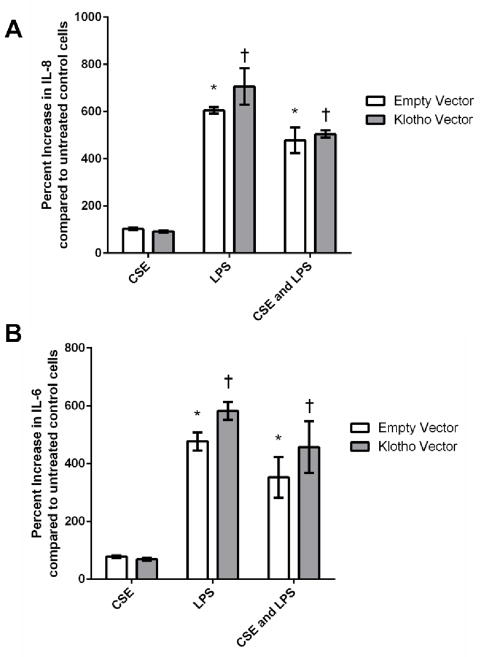

Intracellular KL has been shown to modify the expression of IL-6 and IL-8, which are pro-inflammatory cytokines that are up-regulated in COPD patients, in primary endothelial and fibroblast cells36. KL-overexpressing cells and empty vector control cells were exposed to either CSE, LPS or both for 24 hours and both cell types produced equivalent cytokine levels of both IL-6 and IL-8 (Figure 4), which supports previous results indicating separate functions for the extracellular and intracellular KL forms26.

Figure 4.

Pro-inflammatory cytokine levels are not altered in Klotho-overexpressing cells challenged with CSE and/or lipopolysaccharide (LPS). A) IL-8 and B) IL-6 levels in cell culture supernatants after treatment with either 200 μg/ml of CSE, or 200 ng/ml of LPS, or both for 24 h. Data presented are mean ± SEM of two biological replicates (n = 3 for each experiment). Asterisks indicate a significant difference between mock treated (DMSO) empty vector control cells and control cells exposed to CSE (P < 0.05). Daggers indicate a significant difference between mock treated (DMSO) KL-overexpressing cells and KL-overexpressing cells exposed to CSE (P < 0.05).

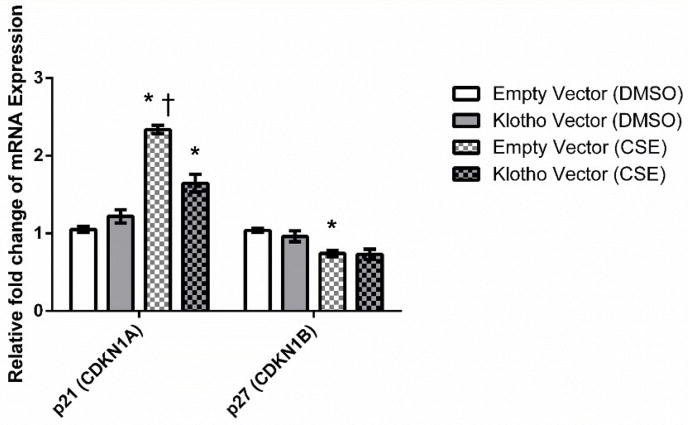

Gene expression levels of two important cell cycle inhibitors, p21 and p27, were quantified in KL-overexpressing cells and empty vector control cells 24 hours after exposure to 200 μg/ml of CSE (Figure 5). CSE induced a significant increase in p21 expression in control cells. However, p21 levels induced by CSE in KL-overexpressing cells were significantly lower compared to control cells (P < 0.05). These data indicate that KL overexpression was able to down-regulate the expression of p21.

Figure 5.

Cigarette smoke extract alters the mRNA expression levels of cell cycle inhibitors. Cells were exposed to 200 μg/ml of CSE for 24 h. Expression levels of p21 and p27 were quantified through RT-qPCR. Data presented are mean relative fold change ± SEM of three biological replicates (n = 3 for each experiment). Asterisks indicate a significant difference between mock treated (DMSO) control cells and cells exposed to CSE (P < 0.05). Dagger indicates a significant difference between control cells and KL-overexpressing cells exposed to CSE (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Stable overexpression of KL in human epithelial cells produces increased levels of secreted Klotho, which can act as an extracellular hormone18. Extracellular KL leads to cytoprotection against CSE by decreasing ROS levels and modifying the expression of the cell cycle inhibitor, p21. Our data support previous findings concerning the expression and function of soluble KL 18, 28, 37. For example, KL is expressed primarily in the kidneys and parathyroid, however, expression levels of KL are very low in pulmonary epithelia17, 28. In addition, membrane bound proteins, such as Klotho, can be cleaved and released as soluble factors by enzymes called sheddases. Previous studies have shown that sheddases include members of proteinase families such as metalloproteinases, A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinases (ADAMs) and serine proteinases. Shedding of the extracellular domain of KL is stimulated by insulin and is mediated by ADAM10 and ADAM1737. Our data clearly indicate that in stably transfected cells, soluble KL levels are significantly increased compared to the membrane bound form. Therefore, the transmembrane domain of Klotho may be cleaved by either ADAM10 and ADAM17 expressed on BEAS-2B cells38, releasing the extracellular domain and mediating its protective effect in this study.

Soluble KL can exist as an intracellular form26 or a secreted extracellular form as described above. Intracellular KL, but not secreted KL, has been shown to down-regulate the production of IL-6 and IL-8 via inhibition of RIG-1 in senescent cells36. Since COPD pathogenesis is mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines that activate and attract white blood cells to the lung, we investigated whether extracellular KL also suppressed pro-inflammatory cytokine release due to CSE and/or LPS. In the present study, extracellular KL did not inhibit the production of IL-6 or IL-8 in response to CSE or LPS supporting previous conclusions36 and identifying distinct functions for the intracellular and secreted form of KL. In addition, the secreted form of KL has two different sizes that include a 130- and a 68-kDa KL fragment26, 37. Currently it is unknown in this study which KL form predominates to mediate its protective effect.

Cigarette smoke induces oxidative stress in pulmonary tissue and cells by generating increased ROS levels that can lead to inflammation and apoptosis in the lung39. KL-overexpressing cells had significantly decreased ROS levels after CSE exposure compared to control cells, indicating that soluble Klotho was able to increase the antioxidant capacity of epithelial cells. Interestingly, basal levels of GSH in control cells and KL-overexpressing cells were similar and both cell types had a significant reduction in GSH levels 6 hours after CSE exposure and GSH depletion with BSO, suggesting that GSH production and the inducible expression of phase II antioxidant genes were not altered. These data indicate that extracellular KL is able to protect cells from CSE-induced cytotoxicity by reducing intracellular ROS levels, possibly by increasing the antioxidant capacity of these cells. Overexpression of KL has been previously shown to combat oxidative stress in vitro in retinal epithelial cells and endothelial cells27, 29. Specifically, oxidative stress induced by IGF-1 was regulated by KL through its ability to activate the FOXO forkhead transcription factor leading to the up-regulation of manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD2)25. A separate study identified that α-Klotho increases nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-related factors 1/2 (Nrf 1/2) transcriptional activity in order to protect from oxidative stress28. In our study, KL-overexpressing cells did not express increased basal levels of SOD2 compared to control cells (Supplemental Figure 3).

Finally, cellular damage to alveolar epithelial cells due to oxidant or CS exposure ultimately leads to lung aging and increased expression of markers of cellular senescence. p21Cip1/Waf1 (encoded by Cdkn1a) has been implicated as a biomarker of senescence40 and is up-regulated in response to CSE12. Cigarette smoke causes premature cellular senescence in pulmonary epithelial cells in vitro, as well as in vivo, and may play a role in the pathogenesis of COPD41. One mechanism by which cigarette smoke causes premature senescence is by increasing the expression levels of cell cycle inhibitors, specifically p21, to stop the cell-cycle progression towards S phase. Previous studies have shown that loss of p21 expression is protective against both oxidative stress and airspace enlargement during CS exposure42. Therefore, the expression of senescence markers were quantified in epithelial cells after CSE exposure. As previously reported, CSE induced a significant increase in p21 expression in vitro43. In response to CSE, p21 levels in control cells were significantly higher than KL-overexpressing cells, whereas no significant differences in p27 expression existed between control and KL over-expressing cells. Previous studies in human fibroblast cells using RNAi to knockdown KL expression observed a significant increase in p21 expression resulting in growth arrest and cellular senescence44. Extracellular KL has also been shown to reduce senescence in human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs) through the p53/p21 pathway30. These data indicate that extracellular KL reduces CSE-induced senescence by suppressing p21 expression, possibly leading to increased cell survival or proliferation in the presence of CSE.

The pathogenesis of COPD is complex and is mediated through different cellular pathways mentioned above, including oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis10. Lung injury, due to chronic oxidant exposure to CS, leads to cellular damage, the disruption of alveolar maintenance, and increased expression of markers of cellular senescence. Ito et al., therefore, first proposed that COPD was a disease due to accelerated aging of the lung45, and others have supported this hypothesis15, 46, 47. Although age does not affect the development of emphysema and small airway remodeling48, Cosio et al. later refined the aging hypothesis and proposed that COPD is a disease of young susceptible smokers that progresses over time, accelerating lung damage, and then manifesting itself later in life47. Consequently, the molecular mechanism of accelerated aging can provide several therapeutic targets for novel intervention strategies against COPD16, 49. We believe that KL is an excellent candidate as a novel intervention strategy for COPD patients due to its protective role against oxidative stress. A recent study identified at least three novel compounds that significantly activate KL expression in rat cells50. The authors correctly indicate that loss of KL expression due to age or disease may contribute to disease progression and loss of homeostatic functions. Interestingly, a recent study has identified a significant decrease in soluble KL levels in sera of smokers compared to non-smokers51. If the expression of KL decreases due to age and CS exposure, circulating KL would be significantly reduced in the lungs of susceptible COPD patients. Therefore, if KL is a protective hormonal protein that enhances the antioxidant capacity of cells, the levels of circulating KL may be able to be modulated through the use of novel activators that may enable pulmonary epithelial cells to resist the oxidant and senescent effects of CS leading to reduced lung damage. Our work presented here suggests that soluble KL reduces CSE-induced cell death by diminishing intracellular ROS levels and suppressing the expression of cell cycle inhibitors leading to continued proliferation and survival.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Human epithelial cells express low levels of membrane bound Klotho.

Overexpression in human epithelial cells increases soluble extracellular Klotho.

Klotho overexpression attenuated CSE-induced cell death by reducing ROS levels.

Acknowledgments

This undergraduate research project was supported by an award from the Minority Access to Research Careers – Undergraduate Student Training in Academic Research Program at Fort Lewis College (Grant 5T34GM092711-03) and the Faculty Development Grant for Traditional Research at Fort Lewis College.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rosenbaum L, Lamas D. Facing a “slow-motion disaster”--the UN meeting on noncommunicable diseases. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2345–2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1112235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akinbami LJ, Liu X. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults aged 18 and over in the United States, 1998–2009. NCHS Data Brief. 2011;(63):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The state of US health, 1990–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310:591–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;61:1–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viegi G, et al. Definition, epidemiology and natural history of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:993–1013. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00082507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogg JC, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2645–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabe KF, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahman I, Adcock IM. Oxidative stress and redox regulation of lung inflammation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:219–242. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00053805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahman I, et al. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal, a specific lipid peroxidation product, is elevated in lungs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:490–495. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2110101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuder RM, Petrache I. Pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2749–2755. doi: 10.1172/JCI60324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowery EM, Brubaker AL, Kuhlmann E, Kovacs EJ. The aging lung. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1489–1496. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S51152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsuji T, Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Cigarette smoke induces senescence in alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:643–649. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0290OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuji T, Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Alveolar cell senescence in patients with pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:886–893. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1374OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walters MS, et al. Smoking accelerates aging of the small airway epithelium. Respir Res. 2014;15:94. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faner R, Rojas M, Macnee W, Agusti A. Abnormal lung aging in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:306–313. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0282PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnes PJ. Mechanisms of development of multimorbidity in the elderly. Eur Respir J. 2015 doi: 10.1183/09031936.00229714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuro-o M, et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390:45–51. doi: 10.1038/36285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurosu H, et al. Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho. Science. 2005;309:1829–1833. doi: 10.1126/science.1112766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imura A, et al. Secreted Klotho protein in sera and CSF: implication for post-translational cleavage in release of Klotho protein from cell membrane. FEBS Lett. 2004;565:143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurosu H, et al. Regulation of fibroblast growth factor-23 signaling by klotho. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6120–6123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500457200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doi S, et al. Klotho inhibits transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta1) signaling and suppresses renal fibrosis and cancer metastasis in mice. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:8655–8665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.174037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu H, et al. Augmented Wnt signaling in a mammalian model of accelerated aging. Science. 2007;317:803–806. doi: 10.1126/science.1143578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cha SK, et al. Removal of sialic acid involving Klotho causes cell-surface retention of TRPV5 channel via binding to galectin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9805–9810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803223105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang Q, et al. The beta-glucuronidase klotho hydrolyzes and activates the TRPV5 channel. Science. 2005;310:490–493. doi: 10.1126/science.1114245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamamoto M, et al. Regulation of oxidative stress by the anti-aging hormone klotho. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38029–38034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509039200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuro-o M. Klotho as a regulator of oxidative stress and senescence. Biol Chem. 2008;389:233–241. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buendia P, et al. Klotho Prevents NFkappaB Translocation and Protects Endothelial Cell From Senescence Induced by Uremia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014 doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravikumar P, et al. alpha-Klotho protects against oxidative damage in pulmonary epithelia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;307:L566–75. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00306.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kokkinaki M, et al. Klotho regulates retinal pigment epithelial functions and protects against oxidative stress. J Neurosci. 2013;33:16346–16359. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0402-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikushima M, et al. Anti-apoptotic and anti-senescence effects of Klotho on vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339:827–832. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacNee W. Pulmonary and systemic oxidant/antioxidant imbalance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:50–60. doi: 10.1513/pats.200411-056SF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nyunoya T, et al. Cigarette smoke induces cellular senescence via Werner’s syndrome protein down-regulation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:279–287. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-320OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshida T, Tuder RM. Pathobiology of cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:1047–1082. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00048.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Starrett W, Blake DJ. Sulforaphane inhibits de novo synthesis of IL-8 and MCP-1 in human epithelial cells generated by cigarette smoke extract. J Immunotoxicol. 2011;8:150–158. doi: 10.3109/1547691X.2011.558529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pryor WA, Prier DG, Church DF. Electron-spin resonance study of mainstream and sidestream cigarette smoke: nature of the free radicals in gas-phase smoke and in cigarette tar. Environ Health Perspect. 1983;47:345–355. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8347345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu F, Wu S, Ren H, Gu J. Klotho suppresses RIG-I-mediated senescence-associated inflammation. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:254–262. doi: 10.1038/ncb2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen CD, Podvin S, Gillespie E, Leeman SE, Abraham CR. Insulin stimulates the cleavage and release of the extracellular domain of Klotho by ADAM10 and ADAM17. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19796–19801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709805104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Estrella C, et al. Role of A disintegrin and metalloprotease-12 in neutrophil recruitment induced by airway epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:449–458. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0124OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacNee W. Pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:258–66. doi: 10.1513/pats.200504-045SR. discussion 290–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tuder RM, Yun JH, Graham BB. Cigarette smoke triggers code red: p21CIP1/WAF1/SDI1 switches on danger responses in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:1–6. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0117TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar M, Seeger W, Voswinckel R. Senescence-associated secretory phenotype and its possible role in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;51:323–333. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0382PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao H, et al. Disruption of p21 attenuates lung inflammation induced by cigarette smoke, LPS, and fMLP in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:7–18. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0342OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fields WR, et al. Gene expression in normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells following in vitro exposure to cigarette smoke condensate. Toxicol Sci. 2005;86:84–91. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Oliveira RM. Klotho RNAi induces premature senescence of human cells via a p53/p21 dependent pathway. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5753–5758. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ito K, Barnes PJ. COPD as a disease of accelerated lung aging. Chest. 2009;135:173–180. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tuder RM, Kern JA, Miller YE. Senescence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2012;9:62–63. doi: 10.1513/pats.201201-012MS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cosio MG, Cazzuffi R, Saetta M. Is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease a disease of aging? Respiration. 2014;87:508–512. doi: 10.1159/000360770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou S, Wright JL, Liu J, Sin DD, Churg A. Aging does not enhance experimental cigarette smoke-induced COPD in the mouse. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chun P. Role of sirtuins in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Pharm Res. 2015;38:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12272-014-0494-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.King GD, et al. Identification of novel small molecules that elevate Klotho expression. Biochem J. 2012;441:453–461. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lam-Rachlin J, et al. Infection and smoking are associated with decreased plasma concentration of the anti-aging protein, alpha-klotho. J Perinat Med. 2013;41:581–594. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2013-0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.