Abstract

Background

Little is known about depressive symptoms in podoconiosis despite the independent contribution of depression to worse health outcomes and disability in people with other chronic disorders.

Method

Two-hundred and seventy-one individuals with podoconiosis and 268 healthy neighbours (individuals from the nearest household in any direction) were investigated for depressive symptoms using a validated Amharic version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The WHO Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHODAS II) tool was used to measure disability. Logistic regression and zero inflated negative binomial regression were used to identify factors associated with elevated depressive symptoms, and disability, respectively.

Results

Among study participants with podoconiosis, 12.6% (34/269) had high levels of depressive symptoms (scoring 5 or more points on the PHQ-9, on two assessments two weeks apart) compared to 0.7% (2/268) of healthy neighbours (p<0.001). Having podoconiosis and being older were significantly associated with increased odds of a high PHQ-9 score (adjusted odds ratios [AOR] 11.42; 95% CI 2.44–53.44 and AOR 1.04; 95% CI 1.00–1.08, respectively). Significant predictors of a higher disability score were having podoconiosis (WHODAS II multiplier value: 1.48; 95% CI 1.39–1.58) and having a high PHQ-9 score (1.07; 95% CI 1.06–1.08).

Conclusion

We recommend integrating evidence-based treatments for depression into podoconiosis interventions.

Keywords: Depression, Ethiopia, Mental health, Neglected tropical disease, Podoconiosis

Introduction

The links between mental health and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) have recently been highlighted as requiring more research.1 Depression is the most significant of mental health problems on a global scale, being the third leading cause of non-fatal disease burden worldwide and representing 4.3% of total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).2 While depression that is co-morbid with angina, diabetes, asthma and arthritis has been shown to make an even larger contribution to disability than the underlying chronic disease,3 the relationship between NTDs and depression, and the respective contribution of both to disability is still poorly described.1

Within Ethiopia, mental illness is the leading non-communicable cause of disease burden measured using DALYs.2 Estimates of the prevalence of depression in community samples from rural Ethiopia vary widely, from a lifetime prevalence estimate of 5.7%,4 up to an estimated prevalence of 9.1% in a national survey carried out as part of the World Health Survey.2,5 Despite such high prevalence, insufficient resources and attention are directed to mental health and depression in Ethiopia, where there are only 0.05 psychiatrists per 100 000 people.6

Podoconiosis is an NTD causing swelling and deformity of the lower legs, often resulting in chronic physical disability and psychosocial consequences7 as well as acute, painful inflammatory episodes known as acute adenolymphangioadenitis (ALA).6 This non-infectious disease affects roughly three million people in Ethiopia alone and the national prevalence among adults was recently estimated at 4%.8 In 2012, a study conducted in the Dembecha district of northern Ethiopia found a significant association between podoconiosis and lower overall quality of life.9 Scores on the Kessler 10 (K10) scale, a screening tool for general mental distress, were also found to be significantly higher in people with podoconiosis than in healthy neighbours.10 The current study aimed to extend the findings of the previous exploration of mental distress in people with podoconiosis by using a culturally validated measure of depressive symptoms to determine their prevalence in individuals with and without podoconiosis. Secondarily, we aimed to investigate the association of depression (as indicated by a high depression score) to disability and podoconiosis.

Methods

Study area and study population

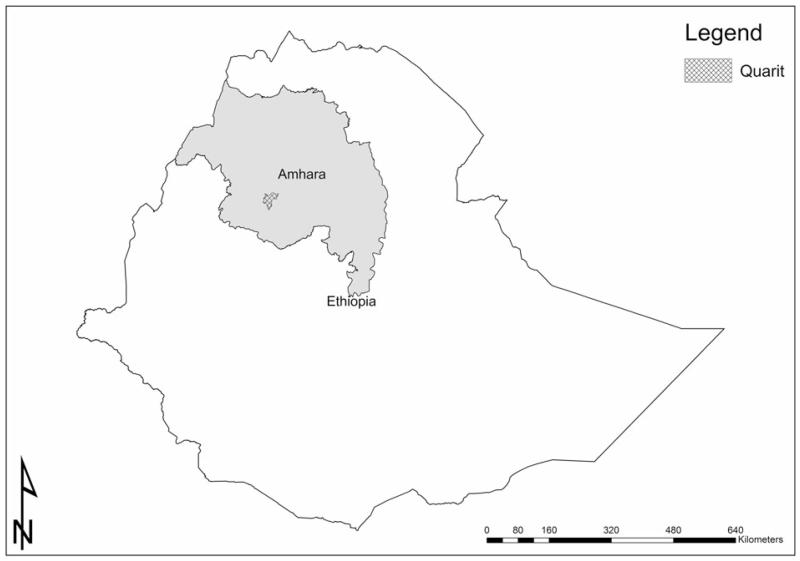

The study was conducted in Quarit district, in the West Gojjam zone of the Amhara regional state of Northern Ethiopia. This district (shown in Figure 1) was chosen as it had a high prevalence of podoconiosis (13.2% of individuals aged over 15 years in two high risk kebeles)8 but was not yet reached by any podoconiosis treatment services. For the purpose of the current study, the 10 kebeles (i.e., the smallest government administrative structure in rural Ethiopia) in the Quarit district with the highest prevalence of podoconiosis were selected.

Figure 1.

Map highlighting study area. Map shows Quarit in the Amhara region of Ethiopia.

Study design

A comparative cross-sectional design was used, and interviewer-administered questionnaire data were collected from people with podoconiosis and from healthy neighbours (individuals from the nearest household in any direction). Approximately equal numbers of men and women were recruited.

Participant selection

The health extension worker (HEW) in each kebele registered all people with podoconiosis in their catchment prior to the survey. Individuals with podoconiosis over 18 years of age were selected from the registration list generated. The patients were selected based on accessibility of their homes for data collectors. Between 27 and 28 patients with podoconiosis were chosen from each of the ten high podoconiosis prevalence kebeles. For each participant with podoconiosis, a neighbour without podoconiosis, of the same sex (where possible) was selected.

Sample size

Taking 12.6% prevalence of depression among healthy controls11 and to detect a 10% difference between groups (i.e., estimating depression to be 22.6% among people with podoconiosis), with a 95% CI and 80% power led to an estimate of 247 participants required in each group. A 10% non-response rate was added, so the final sample size was calculated to be 271 individuals with podoconiosis and 271 healthy neighbours, a total of 542 participants. This was calculated using the Epi-Info Version 6 Stat Calc function (CDC, Atlanta, GA, USA).12

Measures

The main standardized tools used in this study were the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), measuring elevated depressive symptoms, and the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHODAS II) measuring disability. The PHQ-913 is a screening tool for depression. It consists of nine questions that operationalise symptoms of depression (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM IV] criteria) experienced over the previous two weeks. The Amharic version of the PHQ-9 questionnaire has been validated in the primary healthcare setting in the Butajira area, southern Ethiopia, and the optimal cut off point for depression set at five or more (Hanlon C, personal communication). Those individuals with a PHQ-9 score of five or more were revisited two weeks later and the questionnaire was repeated to establish whether depressive symptoms were still present; according to the DSM IV criteria (on which PHQ-9 is based), symptoms should persist for at least two weeks.14 In individuals whose PHQ-9 score was repeated, the second score is used for further analysis. Hence, participants had to score five or more on both occasions to be considered to have a high depressive symptom score.

The WHODAS II tool15 measures general disability by asking questions relating to concentration, physical activities of daily life (e.g., washing oneself) and social interaction over the last 30 days. The Amharic version of this questionnaire has been found to be acceptable and informative in studies in Ethiopia in perinatal women16 and in the general population.17 There is no validated cut-off for degrees of disability and so this score was used as a count variable.

Further variables measured were age, educational level, marital status, wealth index, other major disease co-morbidity, hazardous alcohol drinking (measured by FAST18), family history of mental health problems, social support (measured by the Oslo Social Support score19) and stressful life events (measured using the List of Threatening Events20), as each of these has been previously identified as influencing the risk of mental health problems.21 The wealth index was measured using 16 questions,22 asking whether the participant possessed certain items or amenities (such as electricity or a clock) and about the material of the roof, walls and floor of the house lived in.

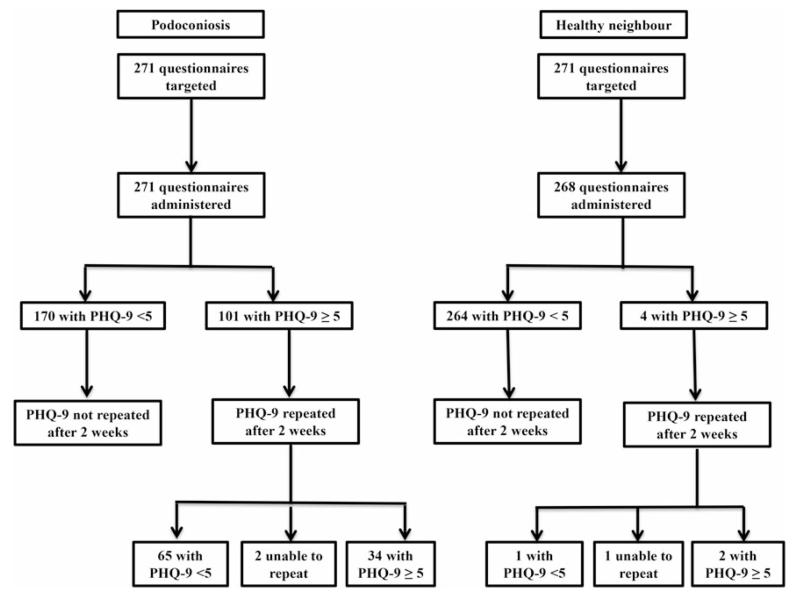

Data collection

The data collection procedure is summarized in Figure 2. The first round of data collection was conducted over five days from 6–10 May 2014. The data were collected by 10 local nurses, one per kebele (the lowest level administration area). Data collectors received one day of training covering the aims of the study, questionnaire administration and pilot work. Over the five days of data collection, three supervisors (JB, KD and AT) visited the kebeles and checked that questionnaires were being filled in completely and accurately. The second round of data collection occurred two weeks later, on 23 and 24 May, when only respondents scoring five or more on the PHQ-9 during the first round were interviewed for the second time.

Figure 2.

Visual representation of data collection process. PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9.13

Data Analysis

Data entry and analysis were done using SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Data were first checked and cleaned. With reference to the wealth index measurement, a household index value was obtained using principle component analysis (PCA) using STATA v. 13.0 (College Station, TX, USA). The resultant scores were divided into three categories as poor, moderate and wealthy. The frequency of high depressive symptom scores (PHQ-9 score greater than or equal to five) was compared between individuals with podoconiosis and healthy neighbours. The mean and median disability (WHODAS II) scores were compared between individuals with podoconiosis and healthy neighbours.

Logistic regression was then carried out, including variables that have previously been shown to be associated with mental illness or depression.10 Although marital status has previously been associated with mental health status, it had no effect on the regression models and so was not included in the final models. Eight variables were added to the model: having podoconiosis, age, having at least one stressful life event, hazardous drinking, other health problems, family history of mental health, wealth status and Oslo Social Support (OSS) score, and adjusted odds ratios were calculated. In order to establish the contribution of depression towards disability (i.e., WHODAS II Score) in people with podoconiosis compared to the healthy neighbours, zero inflated negative binomial regression was carried out using STATA. This model was used because there was a positively skewed distribution of WHODAS II scores with prominent zero inflation (also found in a previous study in Ethiopia16).

To test if there was a significant difference in the contribution of having elevated depressive symptoms and having podoconiosis in reducing the variability in disability scores, the log likelihood was compared between different models: the difference in log likelihood between the model with only pre-specified confounder variables and the model with pre-specified confounders and elevated depressive symptoms was compared with the difference in log likelihood between the model with only confounders and the model with confounders and podoconiosis. Results with p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. The akaike information criterion (AIC) was used to compare non-nested models

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was received from the Research Governance and Ethics Committee of Brighton and Sussex Medical School, and the Amhara Regional Health Bureau. The purpose and nature of the study was described in patient information sheets, which were explained by the interviewing nurse to each participant. The interviewers had training in taking informed consent as well as conducting the questionnaire. When participants were illiterate, consent was confirmed with a thumbprint. All questionnaires were anonymised and the data stored separately from person-identifiable information. Individuals with depressive symptoms were invited to the podoconiosis treatment programme, which runs once a month for three months and for the psychiatric nurse to be present at these sessions to assess and prescribe medication to these individuals as necessary.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

In total, 539 of the target 542 questionnaires were collected (Figure 2). All of the participants were Amhara by ethnicity. The podoconiosis and healthy neighbour groups were not significantly different with respect to occupation and education status. However, the two groups of study participants were significantly different in terms of mean age, marital status, wealth category and presence of leg swelling in another family member. People with podoconiosis were older, less likely to be married and more likely to fall into the ‘poor’ wealth category (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of people with podoconiosis and healthy neighbours, Northern Ethiopia, 2014

| Background characteristics of study participants | Podoconiosis cases n=271a | Healthy neighbours n=268a | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 140 (51.7%) | 155 (57.8%) | NS |

| Female | 131 (48.3%) | 113 (42.2%) | |

| Age categories in years | |||

| 18–20 | 4 (1.5%) | 8 (3.0%) | <0.001 |

| 21–30 | 36 (13.3%) | 62 (23.5%) | |

| 31–40 | 71 (26.3%) | 96 (36.4%) | |

| 41–50 | 78 (28.9%) | 60 (22.7%) | |

| 51+ | 81 (30.0%) | 38 (14.4%) | |

| Area of residence | |||

| Rural | 240 (88.6%) | 237 (88.4%) | NS |

| Urban | 31 (11.4%) | 31 (11.6%) | |

| Number of years in current location | |||

| Less than 10 years | 13 (4.8%) | 11 (4.2%) | NS |

| 10 or more years | 257 (95.2%) | 253 (95.8%) | |

| Occupation | |||

| Employed | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (1.1%) | NS |

| Merchant/trader | 9 (3.3%) | 5 (1.9%) | |

| Farmer | 204 (75.3%) | 216 (80.6%) | |

| Housewife | 31 (11.4%) | 21 (7.8%) | |

| Daily labourer | 16 (5.9%) | 18 (6.7%) | |

| Student | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (1.1%) | |

| Jobless | 7 (2.6%) | 2 (0.7%) | |

| Begging | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Educational status | |||

| Illiterate | 225 (83.0%) | 213 (79.5%) | NS |

| Literate | 43 (15.9%) | 45 (16.8%) | |

| Secondary education (grade7–12) |

3 (1.1%) | 10 (3.7%) | |

| Current marital status | |||

| Married | 194 (74.0%) | 231 (86.5%) | 0.00 |

| Unmarried | 24 (9.2%) | 17 (6.4%) | |

| Divorced | 31 (11.8%) | 14 (5.2%) | |

| Widowed | 13 (5.0%) | 5 (1.9%) | |

| ≥1 other person with leg swelling in household? | |||

| Yes | 56 (21.1%) | 21 (8.0%) | <0.001 |

| No | 210 (78.9%) | 241 (92.0%) | |

| Socio-economic status based on the values of Wealth index | |||

| Poor | 105 (38.7%) | 90 (33.6%) | 0.03 |

| Moderate | 155 (57.2%) | 152 (56.7%) | |

| Wealthy | 11 (4.1%) | 26 (9.7%) | |

NS: not significant.

Some of the variables may not add up to the total because of missing values.

Psychosocial characteristics

There were no significant differences between the two study groups with regard to hazardous alcohol consumption, family history of mental health problems or social support as measured by the OSS scale. Roughly one third of participants had hazardous drinking habits. A family history of mental health problems was reported by 6.3% (17/271) of people with podoconiosis and 2.6% (7/268) of healthy neighbours. There were significantly more health problems and disabilities unrelated to podoconiosis in the group of people with podoconiosis. The latter group was also significantly more likely to have suffered at least one stressful life event in the last six months (Table 2). The stressful life events that differed in frequency between individuals with and without podoconiosis included having a serious illness, injury or assault (25.6% vs 4.5%) and having a major financial crisis (11.1% vs 3.7%).

Table 2.

Depression risk characteristics of people with podoconiosis and healthy neighbours, Northern Ethiopia, 2014

| Podoconiosis cases n=271a | Healthy neighbours n=268a | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazardous alcohol drinking as defined by FAST18 screening tool | |||

| No | 165 (60.9%) | 169 (63.1%) | NS |

| Yes | 106 (39.1%) | 99 (36.9%) | |

| Having family history of mental health problems | |||

| No | 251 (93.7%) | 260 (97.4%) | NS |

| Yes | 17 (6.3%) | 7 (2.6%) | |

| Health condition other than podoconiosis | |||

| No | 228 (84.1%) | 257 (95.9%) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 43 (15.9%) | 11 (4.1%) | |

| Types of health conditions | |||

| Respiratory | 2 (4.7%) | 2 (18.2%) | NS |

| Malaria | 7 (16.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Arthritis | 9 (20.9%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Cardiac | 2 (4.7%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Headache | 5 (11.6%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 3 (7.0%) | 2 (18.2%) | |

| Other | 12 (27.9%) | 2 (18.2%) | |

| Having disability due to other reasons than from podoconiosisb | |||

| No | 264 (97.4%) | 268 (100.0%) | 0.02 |

| Yes | 7 (2.6%) | 0 | |

| Oslo Social Support Scale score (expected value ranges 3–14) | |||

| Poor support (3–8) | 70 (25.8%) | 79 (29.5%) | NS |

| Moderate support (9–11) | 126 (46.5%) | 99 (36.9%) | |

| Strong support (12–14) | 75 (27.7%) | 90 (33.6%) | |

| Suffering at least one stressful life event in the last 6 months (reference is source number 20) | |||

| No | 151 (59.0%) | 216 (84.7%) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 105 (41.0%) | 39 (15.3%) | |

NS: not significant.

Some of the variables may not add up to the total because of missing values.

Included deafness, visual impairment and finger amputation.

Comparing prevalence of high depression scores

The prevalence of elevated depressive symptoms was significantly higher (p-value <0.001) among study participants having podoconiosis (34/269, 12.6%) compared to their healthy neighbours (2/268 = 0.7%). The risk of suicide was 5.2% (14/269) among study participants having podoconiosis and 0.4% (1/268) among their healthy neighbours (p<0.001). Among the study participants, 15 individuals were deemed to be at high suicide risk and were given the opportunity to be seen by psychiatric nurse.

Disability scores in people with and without podoconiosis

The median WHODAS II score was significantly higher in people with podoconiosis than in their healthy neighbours. The mean number of days in which individuals were totally unable to carry out usual activities, or unable to work because of any health condition was 3.1 (±4.3) in the podoconiosis group and 0.2 (±1.1) in the healthy neighbour group (p<0.001). Stage of disease did not have significant impact on the depression score, however having ALA in the past month did; 29/32 participants with a high depression score had ALA in the previous month compared to 124/199 participants with a low depression score (p=0.002).

Factors associated with a high depression score

In the multivariable logistic regression model, people with podoconiosis had 11.4 times higher odds of having elevated depressive symptom score compared to people without podoconiosis (95% CI 2.4–53.4). A one year increase in age was associated with a 3.8% increase in the odds of having a high depressive symptoms score (p=0.035) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results from logistic regression model considering higher depression symptom score (PHQ-9 ≥5) as a binary outcome

| Variable | PHQ-9 score <5 n=500 (%) | PHQ-9 score ≥5 (n=36) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study participants | |||||

| Podoconiosis case | 235/500 (47.0%) | 34/36 (94.4%) | 19.2 (4.6–80.7) | 11.4 (2.4–53.4) | 0.00 |

| Healthy neighbour (ref.) | 265/500 (53.0%) | 2/36 (5.6%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Age in years | |||||

| Continuous | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 1.04 (1.0–1.08) | 0.04 | ||

| ≥1 life event in the last year | |||||

| Yes | 120/475 (25.3%) | 22/33 (66.7%) | 5.9 (2.8–12.6) | 0.5 (0.2–1.1) | NS |

| No (ref.) | 355/475 (74.7%) | 11/33 (33.3%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Hazardous drinking habit (FAST18) | |||||

| Yes | 181/500 (36.2%) | 23/36 (63.9%) | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) | 1.8 (0.8–4.3) | NS |

| No (ref.) | 319/500 (63.8%) | 13/36 (36.1%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Family history of mental health problems | |||||

| Yes | 21/497 (4.2%) | 3/35 (8.6%) | 2.1 (0.6–7.5) | 0.5 (0.1–2.7) | NS |

| No (ref.) | 476/497 (95.8%) | 32/35 (91.4%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Other health problems | |||||

| Yes | 43/500 (8.6%) | 11/36 (30.6%) | 4.7 (2.2–10.2) | 2.4 (0.9–6.2) | NS |

| No (ref.) | 457/500 (91.4%) | 25/36 (69.4%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Oslo Social Support Scale | |||||

| Poor support (ref.) | 145/500 (29.0%) | 4/36 (11.1%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | NA |

| Moderate support | 209/500 (41.8%) | 14/36 (38.9%) | 2.9 (1.2–7.2) | 1.9 (0.5–7.3) | NS |

| Strong support | 146/500 (29.2%) | 18/36 (50.0%) | 0.9 (0.3–2.5) | 3.2 (0.8–13.5) | NS |

| Wealth index | |||||

| Poor (ref.) | 178/500 (35.6%) | 15/36 (41.7%) | 1.0 | 1.0 | NA |

| Middle | 289/500 (57.8%) | 17/36 (47.2%) | 0.7 (0.2–2.2) | 1.0 (0.4–2.3) | NS |

| Wealthy | 33/500 (6.6%) | 4/36 (11.1%) | 0.5 (0.2–1.5) | 3.7 (0.9–15.9) | NS |

NA: not applicable; NS: not significant; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-913; ref: reference.

The contribution of podoconiosis and depression to disability in people with podoconiosis

Factors associated with a higher disability (WHODAS II) score were: having podoconiosis, having a high depression score, living in a rural as opposed to an urban area, being poor on the wealth index, having at least one threatening event in the past six months and having poor social support (Table 4). The expected change in WHODAS II log (count) for one unit increase in PHQ-9 was 1.07 holding other variables constant. A person with podoconiosis had an expected WHODAS II log (count) 1.48 higher than a healthy neighbour. Coefficients are exponentiated, so a multiplier of 1.07 for the association between PHQ-9 and WHODAS II-II score means that for every one point on the PHQ-9 the WHODAS II score increases by 1.07 times (i.e., an increase of 7%). The model without podoconiosis status and depression had an AIC value of 2775.6. When depression was added into the model, the AIC decreased to 2614.1. When depression was replaced by podoconiosis disease status, the AIC decreased to 2587.3. When both podoconiosis disease status and depression were added together, the AIC value decreased further to 2574.7.

Table 4.

Result from multivariabie zero inflated negative binomial regression (ZINB) analysis where WHODAS II-score is the dependent variable

| Covariates | WHODAS II Multiplier value | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Having podoconiosis | 1.48 | 1.39–1.58 | <0.001 |

| Continuous PHQ-9 score | 1.07 | 1.06–1.08 | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.10–1.00 | NS |

| Being male | 0.95 | 0.89–1.01 | NS |

| Illiterate | 1.01 | 0.94–1.08 | NS |

| Living in rural area | 1.13 | 1.00–1.26 | 0.04 |

| Poor on wealth index | 1.10 | 1.02–1.17 | 0.01 |

| Being unmarried | 0.99 | 0.89–1.10 | NS |

| Having hazardous drinking practice | 0.95 | 0.90–1.01 | NS |

| Having at least 1 life event | 1.10 | 1.03–1.18 | 0.01 |

| Having other health problems | 1.04 | 0.95–1.15 | NS |

| Having poor social support | 1.08 | 1.02–1.15 | 0.01 |

NS: not significant; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-913; WHODAS II: WHO Disability Assessment Schedule II. Reference categories for the categorical variables were healthy neighbour, female gender, literate, urban, rich, married, not having hazardous drinking practice, no life threatening events in the last six months, not having other health problems, having moderate or strong social support.

Discussion

Neglected tropical diseases and depression can each have distressing health consequences in their own right. When co-morbidity occurs, the consequences are likely to be further intensified. There is now growing evidence from the NTD sector to support a role for improved mental health and NTD services to reduce risk of both morbidities and their consequences. For the first time, we have investigated the association between podoconiosis and depressive symptoms using a comparison group and repeated measurements to measure persistence of symptoms. This study has shown that having podoconiosis is associated with increased odds of having a high depressive symptom score, and that higher depressive symptom scores and having podoconiosis are both associated independently with higher levels of disability.

A strength of this study is that it drew on expertise of mental health researchers experienced in working in Ethiopia, resulting in the selection of the PHQ-9 tool to measure depressive symptoms. This is the first study among podoconiosis patients to have used repeated measurements of the PHQ-9 for data collection, and it identified a group of people with a clear need for intervention. The PHQ-9 has been recently validated in a rural Ethiopian setting and is thus an appropriate tool for this setting. Unlike the 2012 study,10 this study included data on acute adenolymphangitis and suicidal ideation, which gave more detailed information on those at high risk of suicide to guide intervention. We also included a wide range of standardised and contextually adapted questionnaires about other potential risk factors for depression. This permitted better control of potential confounders during analysis.

A potential limitation was the PHQ-9 cut-off. While this was validated, it still may have introduced inaccuracies: firstly, the cut-off may not have been correct for this setting; secondly, the overlap between physical symptoms of chronic physical ill-health and depression may have led to diagnostic uncertainty over symptoms such as fatigue or sleep problems. Furthermore, using a cut-off means that information about the spread of data is lost and the dataset is simplified. The average and median depression scores were slightly higher in the podoconiosis group than healthy neighbours, however they were still relatively low. Ideally a pilot study using the PHQ-9 should have been conducted so that the cut-off score in this specific community could be determined. This study required high PHQ9 scores at two separate time points to ensure that conservative data was collected in light of these concerns.

Podoconiosis and depression

The current findings support the hypothesis that podoconiosis is associated with depression. The only other variable besides podoconiosis that was shown to be associated with the depression score in the logistic regression model was age. When considering the prevalence of further risk factors for depression in the two study groups, some important differences were observed. There were significantly more other health problems and disabilities among people with podoconiosis than their healthy neighbours. The reason for this might be that podoconiosis is a condition of poorer people who would generally be more at risk of other disabling conditions.23 Alternatively, this could be a direct biological effect as lymphoedema is a ‘low immunity state’ which increases the risk of infections.24 While there is a significant difference in the prevalence of other health conditions between the two groups, the difference is small at 10%, suggesting that other health conditions may contribute towards, but not completely account for, the association between podoconiosis and a higher depression score.

Individuals with podoconiosis who had had ALA in the last month were significantly more likely to be depressed than those that had not; ALA is a very painful condition, and pain is associated with depression, for instance depression has been shown to be a common comorbidity of leprosy patients with neuropathic pain in Ethiopia.25

Both the mean and median WHODAS II scores were significantly higher in podoconiosis cases than in healthy neighbours. This was expected since the physical changes of podoconiosis make many activities more difficult. The median score for many of the activities described in the WHODAS II was 2 (mild difficulties) for people with podoconiosis and 1 (no difficulties) for healthy neighbours. The difficulties were seen to be physical (walking a long distance) as well as social (joining in community activities). People with podoconiosis were also unable to carry out usual activities for a median of 2 days in the last 30 days, whereas the median score for healthy neighbours was zero days. This is likely to have an impact on their economic productivity.

Both podoconiosis and depression contribute to disability status; however, podoconiosis contributed to a slightly greater extent. While the direction of causality cannot be determined, the hypothesis that depression score is independently associated with disability was supported by the findings in this study.

There are a couple of ideas for further research that logically follow from this study. A cohort study would help ascertain the direction of causality in the association between high depression score and disability in people with podoconiosis. More importantly, research into the type of psychosocial intervention that might be beneficial for individuals with podoconiosis is required.

The suggestion that depression is associated with disability independently of podoconiosis shows that depression itself should be addressed in order to relieve some of the burden of disability in podoconiosis patients. Multiple studies have shown that managing psychological stress and depressive symptoms in patients with chronic disease such as rheumatoid arthritis,26 diabetes27 or ischaemic heart disease28 reduces the burden of the underlying chronic disease.29 This is important evidence for policy makers with influence on mental health programmes, but also suggests that charities with programmes catering for patients with podoconiosis will need to widen their services. Evidence-based psychosocial treatment should be included in the management of podoconiosis for those that require it, and must be evaluated in terms of their impact on both podoconiosis and depression. We recognise that it is easy to make this recommendation, but difficult to put it into practice, given the reality of shortages of resources for psychiatry in Ethiopia. In the short term, psychosocial aspects of care of podoconiosis patients might be addressed through contact with a health care professional with special psychological training when patients receive their monthly treatment.

In the longer term, Ethiopia’s National Mental Health Strategy aims to ‘address the mental health needs of all Ethiopians’, including ‘the many people who suffer from common mental disorders’.2 This study identifies a group of people (those with podoconiosis) who are at a higher risk of depression-the most common of the common mental disorders-than the general population. The National Mental Health Strategy also aims to integrate mental health into primary healthcare structures,2 so the referral of patients with podoconiosis to these may be an option in the future. Alongside this, programmes to reduce stigma and spread mental health awareness may enable patients (with and without podoconiosis) to engage in mental health support more willingly.30

Conclusions

Podoconiosis is an NTD, however, mental health, specifically depression, is also neglected in Quarit, Ethiopia and arguably globally. We believe that this research, combined with previous relevant studies, provides sufficient evidence that existing evidence-based packages of care for depression should be integrated into the management of people with podoconiosis. On a broader level, this study complements the growing body of literature concerning the comorbidity of neglected tropical disease and depression and mental illness more generally.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the study participants for their time and engagement in the study and also the ten nurse data collectors who sometimes had to travel long distances by foot in the rain to retrieve this information. We would like to thank the officials of the Quarit Woreda health office. Thanks also go to the staff at the International Orthodox Christian Charity Office in Addis Ababa.

Funding: KD is supported by a Wellcome Trust Research Training Fellowship [grant number 099876]. GD is supported by a Wellcome Trust University award [grant number 091956].

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was received from the Research Governance and Ethics Committee of Brighton and Sussex Medical School, and the Amhara Regional Health Bureau.

References

- 1.Litt E, Baker MC, Molyneux D. Neglected tropical diseases and mental health: a perspective on comorbidity. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health . National Mental Health Strategy 2012/13-2015/2016. Ministry of Health; Addis Ababa: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:851–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Awas M, Kebede D, Alem A. Major mental disorders in Butajira, southern Ethiopia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1999;397:56–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hailemariam S, Tessema F, Asefa M, et al. The prevalence of depression and associated factors in Ethiopia: findings from the National Health Survey. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2012;6:23. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molla YB, Tomczyk S, Amberbir T, et al. Podoconiosis in East and West Gojam Zones, northern Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deribe K, Tomczyk S, Mousley E, et al. Stigma towards a neglected tropical disease: felt and enacted stigma scores among podoconiosis patients in Northern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1178. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deribe K, Brooker SJ, Pullan RL, et al. Epidemiology and individual, household and geographical risk factors of podoconiosis in ethiopia: results from the first nationwide mapping. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92:148–58. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mousley E, Deribe K, Tamiru A, Davey G. The impact of podoconiosis on quality of life in Northern Ethiopia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:122. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mousley E, Deribe K, Tamiru A, et al. Mental distress and podoconiosis in Northern Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. Int Health. 2015;7:16–25. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihu043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelaye B, Williams MA, Lemma S, et al. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for depression screening and diagnosis in East Africa. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210:653–61. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [accessed 20 January 2015];Epi-Info Version 6 Statcalc function. 2010 https://wwwn.cdc.gov/epiinfo/html/ei6_downloads.htm.

- 13.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luciano JV, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Aguado J, et al. The 12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHO-DAS II): a nonparametric item response analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Senturk V, Hanlon C, Medhin G, et al. Impact of perinatal somatic and common mental disorder symptoms on functioning in Ethiopian women: the P-MaMiE population-based cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:340–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mogga S, Prince M, Alem A, et al. Outcome of major depression in Ethiopia: population-based study. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:241–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.013417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodgson R, Alwyn T, John B, et al. The FAST Alcohol Screening Test. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:61–6. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalgard OS, Dowrick C, Lehtinen V, et al. Negative life events, social support and gender difference in depression: a multinational community survey with data from the ODIN study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:444–51. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brugha T, Bebbington P, Tennant C, Hurry J. The List of Threatening Experiences: a subset of 12 life event categories with considerable long-term contextual threat. Psychol Med. 1985;15:189–94. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002105x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence Universities of Nijmegen and Maastricht. Prevention Research Centre . Summary Report / a report of the World Health Organization Dept. of Mental Health and Substance Abuse; in collaboration with the Prevention Research Centre of the Universities of Nijmegen and Maastricht. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2004. Prevention of Mental Disorders Effective Interventions and Policy Options. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rutstein SO, Johnson K. The DHS Wealth Index. ORC Macro; Calverton, MD: 2004. (DHS Comparative Reports No. 6). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davey G, Tekola F, Newport MJ. Podoconiosis: non-infectious geochemical elephantiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:1175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NLN Medical Advisory Committee . TOPIC: The Diagnosis And Treatment Of Lymphedema. Position Statement of the National Lymphedema Network. National Lymphedema Network; San Francisco, CA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haroun OM, Hietaharju A, Bizuneh E, et al. Investigation of neuropathic pain in treated leprosy patients in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Pain. 2012;153:1620–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santiago T, Geenen R, Jacobs JW, Da Silva JA. Psychological factors associated with response to treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21:257–69. doi: 10.2174/1381612820666140825124755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lustman P, Freedland K, Griffith L, Clouse R. Fluoxetine for depression in diabetes: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:618–23. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.5.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollock BG, Laghrissi-Thode F, Wagner WR. Evaluation of platelet activation in depressed patients with ischemic heart disease after paroxetine or nortriptyline treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20:137–40. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200004000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simon GE. Treating depression in patients with chronic disease: recognition and treatment are crucial; depression worsens the course of a chronic illness. West J Med. 2001;175:292–3. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.175.5.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh AR. The task before psychiatry today redux: STSPIR. Mens Sana Monogr. 2014;12:35–70. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.130295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]