Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the commonest cause of disability in young adults. While there is increasing choice and better treatments available for delaying disease progression, there are still, very few, effective symptomatic treatments. For many patients such as those with primary progressive MS (PPMS) and those that inevitably become secondary progressive, symptom management is the only treatment available. MS related symptoms are complex, interrelated, and can be interdependent. It requires good understanding of the condition, a holistic multidisciplinary approach, and above all, patient education and empowerment.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, neurology, symptoms, therapy

Introduction

MS is a chronic progressive neurological condition. It is estimated that approximately 2.3 million individuals are affected worldwide and this appears to be increasing.[1] It is one of the commonest cause of disability in young individuals, thus causing severe burden to individuals, their families, and ultimately on societies. While disease modifying treatments help slow the progression, symptomatic treatments are important in helping individuals fulfill their personal, social, and occupational roles and improve quality of life, for as long as possible. Unfortunately symptomatic treatments specifically for MS are lagging behind those for disease modification. It is therefore important that patients are informed, educated, and have access to multidisciplinary teams to manage complex symptoms of MS.

Is it a relapse?

Whenever patients present with symptoms, it is important to clarify if these represent relapse or not.[2] A relapse is defined as new neurological symptoms that are typical for MS, last longer than 24 h, in absence of a febrile illness. Cognitive and neuropsychiatric relapses can be easily missed. Any symptom that has been going on for 3 months or longer is generally not considered a relapse.

Cognitive and psychiatric symptoms (anxiety, depression, other psychiatric conditions, memory, and executive dysfunction)

Cognitive dysfunction and psychiatric conditions are commonly encountered in MS patients.[3] Monitoring of MS patients often is biased towards physical disability and therefore these can be overlooked, yet have significant impact on adherence to disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) and quality of life.[4] Anxiety and depression is particularly common and more prevalent than normal population. Depression can worsen cognitive dysfunction. Cognitive behavior therapy is helpful.[5] Questionnaires such as Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale may be used as a quick screening tool.[6] Further input from a neuropsychologist or psychiatrist may be necessary.

Up to 50% patients will have cognitive impairment within 5 years following clinically isolated syndrome,[7] and the prevalence increases with progressive stage of the disease. Evidence for treatments for improving cognition is lacking,[8] and treatments can be difficult to study in a heterogeneous and progressive condition such as MS. From an observational study of treatment for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) with interferon beta 1a, there is evidence to suggest early treatment may reverse cognitive impairment.[9] Intensive neuropsychological rehabilitation therapy is helpful in patients with low level of disability.[10] Unfortunately there is lack of good trial data to consider specific rehabilitation strategies in wider MS population.[11]

Fatigue, Sleep, Restless Legs

Fatigue is one of the common causes of loss of quality of life in patients with MS, independent of disability or depression. It is considered the most debilitating symptom and reported by at least 75% of patients.[12,13] It is difficult to define and often described as lethargy, exhaustion, tiredness, and subjective lack of physical and/or mental energy. Assessing fatigue is difficult as it is a subjective symptom. Fatigue Severity Scale, a patient generated scale, has been validated in assessing impact of fatigue and is useful in clinical practice.[14] Causes of fatigue are complex and multifactorial. These may relate to central pathological processes, physical disability, pain, poor quality of sleep, and medications. Consider nonpharmacological strategies first. Energy conserving strategies have been shown to be effective.[15] Aerobic exercises and rehabilitation regimes can be beneficial in some patients.[16,17] Cooling of body temperature may help in patients with thermosensitive symptoms.[18,19] Depression is very common and is directly associated with fatigue. Treating depression can improve fatigue.[20] A review of pharmacotherapies for MS symptoms[21] found a few small trials with pemoline, 4-aminopyridine, 3,4-aminopyridine, L-carnitine, amantadine, and modafinil. There is very limited evidence for amantadine and modafinil. In our experience, amantadine is not particularly helpful and most patients stop after a brief trial. Modafinil may be particularly suited for those patients with fatigue and hypersomnolence; although, there are long-term safety concerns with modafinil. Pain medications, antispasticity drugs, and anticholinergics for bladder overactivity can cause tiredness, and their use should be reviewed. Other common causes of fatigue, for example, hypothyroidism, vitamin and nutrient deficiencies, and diabetes should be considered, and can be easily excluded.

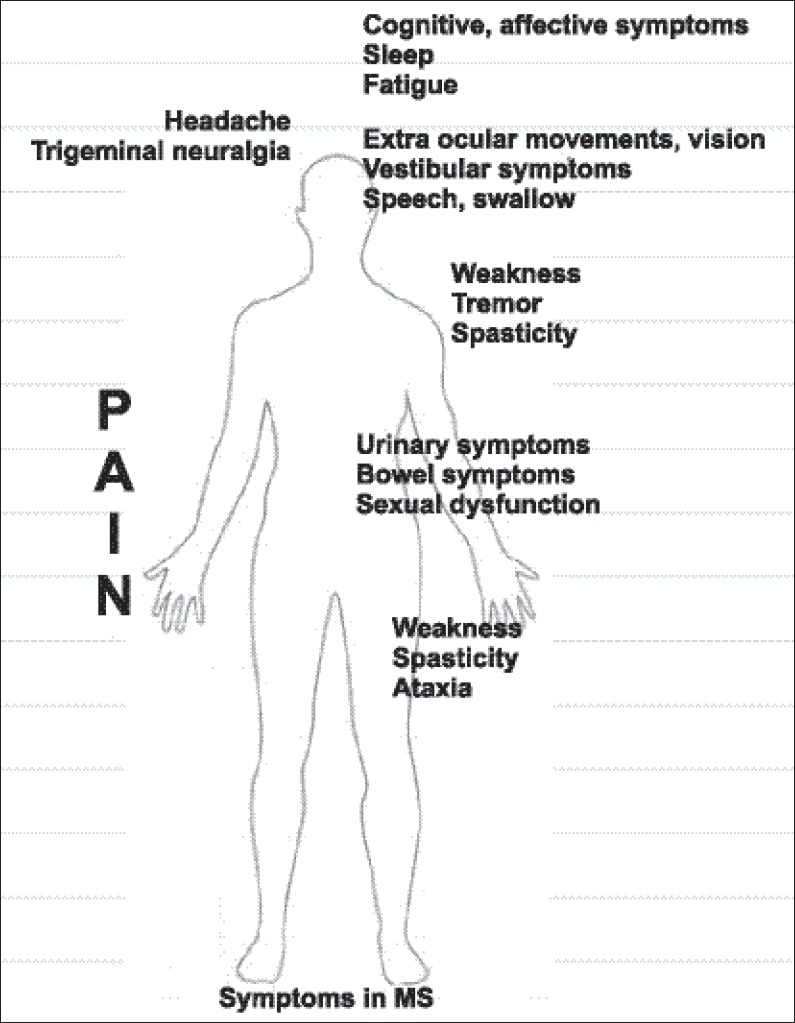

Figure 1.

Symptoms in MS

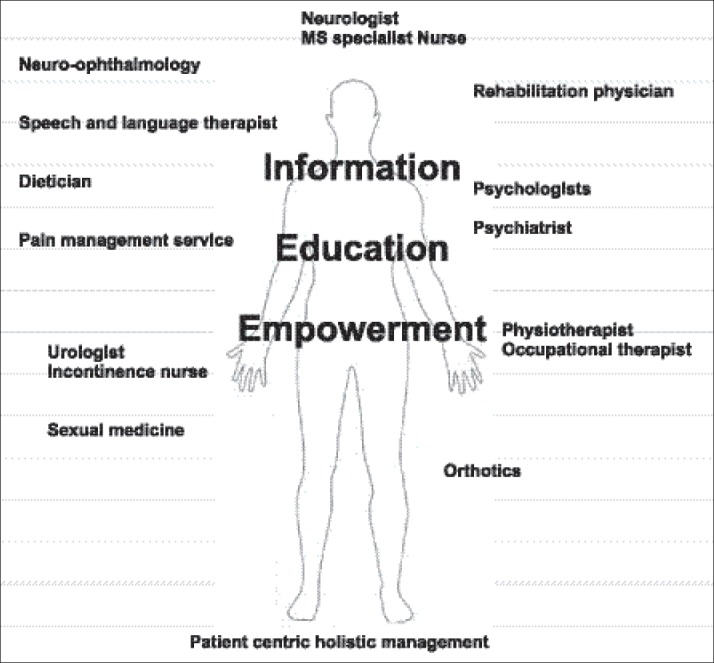

Figure 2.

Patient centric holistic management

Good quality sleep is important in managing fatigue and cognitive symptoms.[22] Sleep can be disturbed due to pain, bladder dysfunction, and spasticity. Also other sleep disorders[23] such as chronic insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA),[24] hypersomnolence, and narcolepsy can occur in MS. Educate patients with sleep hygiene. Treat pain, spasticity, and bladder symptoms adequately. Sleep diary and sleepiness scale such as Epworth scale may be useful in screening patients for sleep disorders.

Restless limbs are common in MS.[23] The incidence increases with worsening disability. Consider DOPA agonists for resistant and severe symptoms.

Headache Syndromes, Trigeminal Neuralgia

Headache syndromes are common in MS patients and correlate with disability and quality of life.[25] Migraine with aura can be a presenting feature in MS.[25] Apart from treating the headaches with medical treatments, stress and fatigue can often trigger severe headaches and should be identified and managed.

Trigeminal neuralgia is more prevalent in MS patients than the population with 20 times higher risk.[26,27] In about one-third, this can be bilateral. There is only limited evidence with open label studies that show beneficial effect of pharmacotherapy.[27] These are gabapentin, alone or in combination with lamotrigine, carbamazepine, also, lamotrigine alone, topiramate, and misoprostol. A systematic review[28] found that surgical treatments including microvascular decompression are equally beneficial in drug resistant cases.

There is currently no systematic data on prevalence of greater occipital neuralgia and hypoglossal neuralgia in MS.

Pain

Neuropathic pain is common in MS with point prevalence of 50%, with at least 75% patients having suffered pain within a month of assessment.[29] It is caused by involvement of sensory pathways. Also spasticity can cause painful spasms and jerks, and management of this is discussed separately. There is very limited evidence for specific drugs for managing pain in MS. Antiepileptic drugs are commonly used in combination with conventional pain medications and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended step ladder approach should be followed. A recent study (phase 3 trial) of Δ (9)-tetra-hydro cannabinol (THC)/cannabidiol (CBD) oral spray for pain did not meet primary endpoint.[30] Further subanalysis suggests that some patients may benefit and needs further consideration. A large, randomized, double-blind trial of duloxetine showed significant pain control.[31] There is some evidence of treatment effect for gabapentin, pregabalin, lamotrigine, and topiramate from small mostly open label trials.[32]

Visual disturbance (diplopia, oscillopsia, visual impairment, Pulfrich phenomenon)

Oculomotor disorders are common, but underdiagnosed in MS.[33] These occur due to lesions in brain stem and cerebellum. Gaze abnormalities cause internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO), wall-eyed bilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia (WEBINO), one and half syndrome, sixth-nerve palsy, and less commonly involvement of third and fourth. Saccadic intrusions, and nystagmus can cause reduced visual acuity and oscillopsia. Vestibular involvement causes skew deviation resulting in vertical diplopia, ocular tilt reaction, and ataxia. Detailed examination of eye movements is important in localizing lesion and treating accordingly. Antiepileptic drugs are often used for disorders of saccadic intrusions. Nystagmus, in particularly pendular, can be quite distressing and difficult to treat. Drugs such as baclofen, gabapentin, memantin, 3,4-diaminopyridine, fampridine, and botulinum toxin injections have been shown to have some benefit.[8] Memantine should be used with caution as it can make MS symptoms worse.[34] Other nonpharmacological strategies such as prism and patching of one eye may be considered where appropriate.

Optic neuritis occurs in 50% cases of MS,[35] and can be the presenting syndrome in up to 20%.[36] While majority of patients (90%) make normal to near normal recovery, most patients experience chronic sequelae.[37] These include; scotomatas, decreased contrast sensitivity, color desaturation, stereoillusion (Pulfrich phenomenon). Input from neuro-ophthalmological services should be sought in assessment and management of various visual symptoms.

Vestibular Symptoms

True vertigo occurs in 20% patients with MS and about 78% have symptoms related to impaired balance. These usually relate to brainstem lesions. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is still the commonest cause of positional vertigo in MS, though MS lesions can mimic this occasionally.[38]

Speech and Swallowing

Swallowing difficulties are common in MS patients and estimated between 24 and 55%.[39,40] These occur as disability progresses and typically occur with brainstem lesions, as well with severe cognitive impairment. These lead to poor quality of life, malnourishment, and risk of aspiration pneumonia.

Speech can be affected as a result of bulbar dysfunction, cerebellar syndrome, fatigue, dry mouth (local causes, anticholinergics), slow thinking, and low mood. Speech and language therapists are instrumental in assessment and management of swallowing and speech.[41]

Tremors and Ataxia

Tremors are common in MS and occur in 40-60% of patients.[42] Tremors can be postural as well as kinetic and can be quite difficult to treat. Case reports and small studies provide scant evidence for specific treatments. Isoniazide in high doses, carbamazepine, propranolol, glutethmide, 4-aminopyridine, and topiramate have been reported to provide some benefit.[42,43,44] A trial with cannabinoids was negative.[45,46] Physiotherapy, orthoses, and limb cooling may be beneficial.[42] For severe treatment resistant tremor thalamotomy or thalamic stimulation has been tried to some degree of success.[47]

Management of ataxia is difficult and treatment is supportive only. A Cochrane review in 2007[48] found no evidence for specific treatments. A systemic review of trials with physical therapies showed some beneficial effect.[49]

Weakness

Weakness is a common (70%) and disabling symptom amongst MS patients.[50] It not only can result in loss of function, but also painful contractures in long term. Physical therapy, aerobic exercises, and assistive devices can be helpful.[51] 4-aminopyridine[52] can help with fatigue and temperature related weakness, but long-term use is limited by short duration of action and side effects. A slow release preparation appears to be better tolerated and effective.

Spasticity

Up to 90% of the patients with MS will experience spasticity during the course of their disease.[53] It is a painful disabling symptom and significantly limits quality of life. Aim of managing spasticity[54] is to improve discomfort, mobility, posture, carer burden, maintain hygiene, and improve body image. Also in long-term, these help prevent contractures and skin ulcers. There is very limited, good quality evidence for treatments in spasticity and is derived from trials in MS as well as other neurological conditions.[47,55,56] Quantifying spasticity is difficult and clinical scale such as Ashworth scale that is commonly used has significant limitations.[57,58] It does not correlate well with disability and is not sensitive to change. To assess treatment effect, patient generated questionnaires such as MSSS and functional assessment such as 25 foot walk time may be practical and useful in clinical practice.[59,60] Nonpharmacological treatments such as physiotherapy and orthotic devices can be helpful.[16] In pharmacotherapy,[8] gamma-aminobutyric acid-ergic (GABAergic) drugs such as baclofen or gabapentin may be considered as first line treatments. Clonazepam may be helpful particularly for bed time spasms. Other alternatives such as tizanidine (alpha-2 adrenergic) or dantrolene (blockade of calcium release in muscle) may be considered. Intramuscular botulinum toxin[60,61] can be effective, particularly in localized spasticity. A recent trial with THC/CBD (Nabiximol) in MS showed benefit in patient-reported outcomes.[62] This can be tried in patients that have failed other common therapies. In nonresponders, it should be discontinued after trial of 4 weeks. A small trial of low dose Naltrexone in PPMS patients showed significant improvement in spasticity[63] (using Ashworth Scale as well as Visual Analogue Pain Scale). Intrathecal baclofen[64] can be helpful usually as a palliative measure in severely disabled, nonambulatory patients (Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) > 7), and in a few well-selected ambulatory patients. This treatment needs to be undertaken in specialist units, wherein patients can have close access for review and managing any adverse events that may occur. These drugs are often associated with significant side effects. Also patients can depend on their spasticity to maintain posture, or weight-bear, reducing spasticity can worsen function. Close review is therefore important. Other factors such as pain, ulcer, bladder infection, and constipation can increase spasticity, and therefore should be looked for and treated.

Gait

Gait may be affected due to weakness, spasticity, ataxia, and lack of sensation. It is important to optimize pain and spasticity treatment. Walking aids should be considered where appropriate. Physiotherapy,[65] aerobic exercises,[56] cooling body temperature,[18] and appropriate foot orthoses (AFO; foot drop splint, foot up splint) can improve gait.

Other specific measures like dalfampridine,[66] a metabolite of 4-aminopyridine, has shown to improve gait in a recent trial. There was improvement in 25-foot timed walk and improvement in patient-reported outcomes. Functional electrical stimulation (FES) can help with gait difficulties in some patients with foot drop who are able to weight-bear.[67]

Bladder

During the course of MS, almost all of the patients will experience some bladder symptoms and these become prevalent as the disability progresses.[68] Patients often have combination of detrusor overactivity, initiation and emptying, and detrusor sphincter dyssynergia. In symptomatic patients, initial assessment with intake and output chart can be helpful, especially for considering nonpharmacological therapies, for example, reducing excessive caffeinated drinks, avoiding fluid intake at bed time, and moderating intake as per thirst rather than compulsive intake. When considering treatment for symptoms of predominant bladder overactivity (urgency, frequency, urge incontinence, and nocturia), it is useful to exclude impaired bladder emptying, and this can be easily done with bladder ultrasound scan to measure post void volume. A volume of 100 ml or more or more than one-third of bladder volume would suggest impaired emptying, and therefore can cause urinary retention with anticholinergic treatments used for bladder overactivity. Pelvic floor exercises and behavior therapy has shown to help bladder frequency or urgency.[69,70] While robust clinical trial evidence is limited,[71] a number of anticholinergic drugs are used commonly as first-line pharmacotherapy. These include oxybutynin, trospium, tolterodine, propiverine, solifenacin, derifenacin, and mirabegron. Mirabegron, the only B3 adrenoceptor agonist, appears to be equally effective and with less incidence of side effects such as dry mouth.[72]

There is good evidence that desmopressin can help with nocturia or day time frequency.[73] Its frequent and long-term use can cause significant hyponatremia, particularly in elderly. Therefore its use should be closely monitored.

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of cannabinoids failed to meet primary end points, but there was evidence of improvements in patient-centered measures.[46]

There is some lower grade evidence for intravesical capsaicin (vanilloids), and this may not be available easily.[71]

In patients that have failed behavior therapy and oral treatments, there is robust evidence for effective treatment using detrusor injection with onabotulinum toxin-A.[74]

On failure of these treatments, consider intermittent self-catheterization or long-term catheterization.

Patients who have significant post void residual volume, hesitancy likely have impairment of emptying and/or detrusor sphincter dyssynergia. Lower abdominal pressure and external bladder stimulation with a vibrator may be useful in helping emptying bladder.[75] Intermittent, long-term, or suprapubic catheter may be considered. This will depend on patient's disability and carer support. Urodynamic studies may be helpful to clarify the defect precisely before any intervention is undertaken.

Bowel

Bowel symptoms are common in MS.[76] In a large survey, 68% patients had constipation and/or fecal incontinence.[77] There is limited good quality for specific treatments and treatments are of empirical nature. Bulking laxatives are commonly used. Biofeedback training has been shown to help with incontinence.[78] Some patients may benefit from transanal irrigation treatment.[79] Sacral nerve stimulation may be considered where other treatments have failed.[80] This is only possible in specialist units and the study data while promising is quite small, and positive results may relate to careful patient selection.

Sexual Dysfunction

Sexual dysfunction is very common in sufferers of MS. Up to 90% of patients can experience some form of difficulty.[81] Often patients find it hard to discuss this, be it with their partners or with their healthcare professionals. This can make it difficult to get help, put strain on relationships, and cause significant negative impact on quality of life. Women can experience loss of sensation, lack of desire, dyspareunia, and anorgasmia.[82] Men can experience erectile dysfunction, lack of libido, and anorgasmia.[83] These may be secondary to medications such as antidepressants (some better than others), anticholinergics, and antiepileptics. There is limited trial evidence for specific treatments. It is important to review medication and withdraw if likely cause. Treat any depression. It is helpful to manage fatigue better, plan sexual activity, and using lubricants. Counseling with advice on open discussion, intimacy, and nongenital stimulation is helpful. Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors are helpful for erectile dysfunction in men, as well as improve orgasmic function in women.[84] Other treatments for erectile dysfunction such as intracavernous alprostadil may be used. For failure of ejaculation during sexual intercourse, penile vibratory stimulation can be helpful; this can be further enhanced by oral midodrine.[83]

General considerations

Team approach is important. MS nurses play a crucial role. When prescribing treatments, it is important to follow local regulations and many drugs or treatments may not be licensed and may need special permission from regulators. Individual treatments can be expensive to patients or health authorities, and it is important to consider cost effectiveness for the patient and to the society in general.

There is high usage of complementary alternative treatments amongst MS patients. This reflects not only the limitation of modern medicine, but also patient's desire to feel empowered and in control. It is important that the patients are well-informed, educated, and involved in deciding their treatments.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

I have received educational grants to attend national and international conferences by TEVA, Biogen, Merk Serono, Novartis. I have received payments for lecture from Biogen and have attended advisory board meeting for Novartis.

References

- 1.Epidemiology of MS [Internet] [Last accessed on 2015 Apr 23]. Available from: http://www.msif.org/research/epidemiology-of-ms .

- 2.Leary SM, Porter B, Thompson AJ. Multiple sclerosis: Diagnosis and the management of acute relapses. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:302–8. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.029413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marrie RA, Reingold S, Cohen J, Stuve O, Trojano M, Sorensen PS, et al. The incidence and prevalence of psychiatric disorders in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Mult Scler. 2015;21:305–17. doi: 10.1177/1352458514564487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Likosky W, Gatto N, Baumann KA, Rudick RA. Treatment of depression improves adherence to interferon beta-1b therapy for multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:531–3. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550170015009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas PW, Thomas S, Hillier C, Galvin K, Baker R. Psychological interventions for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004431.pub2. CD004431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Honarmand K, Feinstein A. Validation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale for use with multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2009;15:1518–24. doi: 10.1177/1352458509347150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reuter F, Zaaraoui W, Crespy L, Faivre A, Rico A, Malikova I, et al. Frequency of cognitive impairment dramatically increases during the first 5 years of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82:1157–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.213744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson AJ, Toosy AT, Ciccarelli O. Pharmacological management of symptoms in multiple sclerosis: Current approaches and future directions. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:1182–99. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mori F, Kusayanagi H, Buttari F, Centini B, Monteleone F, Nicoletti CG, et al. Early treatment with high-dose interferon beta-1a reverses cognitive and cortical plasticity deficits in multiple sclerosis. Funct Neurol. 2012;27:163–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattioli F, Stampatori C, Scarpazza C, Parrinello G, Capra R. Persistence of the effects of attention and executive functions intensive rehabilitation in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2012;1:168–73. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitolo M, Venneri A, Wilkinson ID, Sharrack B. Cognitive rehabilitation in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. J Neurol Sci. 2015;354:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krupp L. Fatigue is intrinsic to multiple sclerosis (MS) and is the most commonly reported symptom of the disease. Mult Scler. 2006;12:367–8. doi: 10.1191/135248506ms1373ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lerdal A, Celius EG, Krupp L, Dahl AA. A prospective study of patterns of fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:1338–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dittner AJ, Wessely SC, Brown RG. The assessment of fatigue: A practical guide for clinicians and researchers. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:157–70. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathiowetz VG, Finlayson ML, Matuska KM, Chen HY, Luo P. Randomized controlled trial of an energy conservation course for persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11:592–601. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1198oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiles CM, Newcombe RG, Fuller KJ, Shaw S, Furnival-Doran J, Pickersgill TP, et al. Controlled randomised crossover trial of the effects of physiotherapy on mobility in chronic multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:174–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.2.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burschka JM, Keune PM, Oy UH, Oschmann P, Kuhn P. Mindfulness-based interventions in multiple sclerosis: Beneficial effects of Tai Chi on balance, coordination, fatigue and depression. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:165. doi: 10.1186/s12883-014-0165-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwid SR, Petrie MD, Murray R, Leitch J, Bowen J, Alquist A, et al. NASA/MS Cooling Study Group. A randomized controlled study of the acute and chronic effects of cooling therapy for MS. Neurology. 2003;60:1955–60. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000070183.30517.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds LF, Short CA, Westwood DA, Cheung SS. Head pre-cooling improves symptoms of heat-sensitive multiple sclerosis patients. Can J Neurol Sci. 2011;38:106–11. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100011136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohr DC, Hart SL, Goldberg A. Effects of treatment for depression on fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:542–7. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000074757.11682.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Sa JC, Airas L, Bartholome E, Grigoriadis N, Mattle H, Oreja-Guevara C, et al. Symptomatic therapy in multiple sclerosis: A review for a multimodal approach in clinical practice. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2011;4:139–68. doi: 10.1177/1756285611403646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaminska M, Kimoff RJ, Schwartzman K, Trojan DA. Sleep disorders and fatigue in multiple sclerosis: Evidence for association and interaction. J Neurol Sci. 2011;302:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veauthier C. Sleep disorders in multiple sclerosis. Review. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2015;15:21. doi: 10.1007/s11910-015-0546-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braley TJ, Segal BM, Chervin RD. Obstructive sleep apnea and fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10:155–62. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tabby D, Majeed MH, Youngman B, Wilcox J. Headache in multiple sclerosis: Features and implications for disease management. Int J MS Care. 2013;15:73–80. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2012-035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katusic S, Williams DB, Beard CM, Bergstralh EJ, Kurland LT. Epidemiology and clinical features of idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia and glossopharyngeal neuralgia: Similarities and differences, Rochester, Minnesota, 1945-1984. Neuroepidemiology. 1991;10:276–81. doi: 10.1159/000110284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Santi L, Annunziata P. Symptomatic cranial neuralgias in multiple sclerosis: Clinical features and treatment. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114:101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montano N, Papacci F, Cioni B, Di Bonaventura R, Meglio M. What is the best treatment of drug-resistant trigeminal neuralgia in patients affected by multiple sclerosis? A literature analysis of surgical procedures. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115:567–72. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Connor AB, Schwid SR, Herrmann DN, Markman JD, Dworkin RH. Pain associated with multiple sclerosis: Systematic review and proposed classification. Pain. 2008;137:96–111. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langford RM, Mares J, Novotna A, Vachova M, Novakova I, Notcutt W, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of THC/CBD oromucosal spray in combination with the existing treatment regimen, in the relief of central neuropathic pain in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2013;260:984–97. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6739-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vollmer TL, Robinson MJ, Risser RC, Malcolm SK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of duloxetine for the treatment of pain in patients with multiple sclerosis. Pain Pract. 2014;14:732–44. doi: 10.1111/papr.12127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan N, Smith MT. Multiple sclerosis-induced neuropathic pain: Pharmacological management and pathophysiological insights from rodent EAE models. Inflammopharmacology. 2014;22:1–22. doi: 10.1007/s10787-013-0195-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rougier MB, Tilikete C. Ocular motor disorders in multiple sclerosis. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2008;31:717–21. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(08)74390-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villoslada P, Arrondo G, Sepulcre J, Alegre M, Artieda J. Memantine induces reversible neurologic impairment in patients with MS. Neurology. 2009;72:1630–3. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000342388.73185.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balcer LJ. Clinical practice. Optic neuritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1273–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp053247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beck RW, Gal RL. Treatment of acute optic neuritis: A summary of findings from the optic neuritis treatment trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:994–5. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.7.994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balcer LJ, Miller DH, Reingold SC, Cohen JA. Vision and vision-related outcome measures in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2015;138:11–27. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frohman EM, Kramer PD, Dewey RB, Kramer L, Frohman TC. Benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo in multiple sclerosis: Diagnosis, pathophysiology and therapeutic techniques. Mult Scler. 2003;9:250–5. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms901oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guan X, Wang H, Huang H, Meng L. Prevalence of dysphagia in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Sci. 2015;36:671–81. doi: 10.1007/s10072-015-2067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henze T, Rieckmann P, Toyka KV Multiple Sclerosis Therapy Consensus Group of the German Multiple Sclerosis Society. Symptomatic treatment of multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Therapy Consensus Group (MSTCG) of the German Multiple Sclerosis Society. Eur Neurol. 2006;56:78–105. doi: 10.1159/000095699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown SA. Swallowing and speaking challenges for the MS patient. Int J MS Care. 2000;2:4–14. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koch M, Mostert J, Heersema D, De Keyser J. Tremor in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2007;254:133–45. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0296-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schroeder A, Linker RA, Lukas C, Kraus PH, Gold R. Successful treatment of cerebellar ataxia and tremor in multiple sclerosis with topiramate: A case report. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33:317–8. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181f84a39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schniepp R, Jakl V, Wuehr M, Havla J, Kumpfel T, Dieterich M, et al. Treatment with 4-aminopyridine improves upper limb tremor of a patient with multiple sclerosis: A video case report. Mult Scler. 2013;19:506–8. doi: 10.1177/1352458512461394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fox P, Bain PG, Glickman S, Carroll C, Zajicek J. The effect of cannabis on tremor in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;62:1105–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118203.67138.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koppel BS, Brust JC, Fife T, Bronstein J, Youssof S, Gronseth G, et al. Systematic review: Efficacy and safety of medical marijuana in selected neurologic disorders: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;82:1556–63. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Torres CV, Moro E, Lopez-Rios AL, Hodaie M, Chen R, Laxton AW, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral intermediate nucleus of the thalamus for tremor in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurosurgery. 2010;67:646–51. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000375506.18902.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mills RJ, Yap L, Young CA. Treatment for ataxia in multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD005029. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005029.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fonteyn EM, Keus SH, Verstappen CC, Schols L, de Groot IJ, van de Warrenburg BP. The effectiveness of allied health care in patients with ataxia: A systematic review. J Neurol. 2014;261:251–8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-6910-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoang PD, Gandevia SC, Herbert RD. Prevalence of joint contractures and muscle weakness in people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:1588–93. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.854841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kjolhede T, Vissing K, Dalgas U. Multiple sclerosis and progressive resistance training: A systematic review. Mult Scler. 2012;18:1215–28. doi: 10.1177/1352458512437418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jensen HB, Ravnborg M, Dalgas U, Stenager E. 4-Aminopyridine for symptomatic treatment of multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2014;7:97–113. doi: 10.1177/1756285613512712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rizzo MA, Hadjimichael OC, Preiningerova J, Vollmer TL. Prevalence and treatment of spasticity reported by multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2004;10:589–95. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1085oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nair KP, Marsden J. The management of spasticity in adults. BMJ. 2014;349:g4737. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shakespeare DT, Boggild M, Young C. Anti-spasticity agents for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;4:CD001332. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feinstein A, Freeman J, Lo AC. Treatment of progressive multiple sclerosis: What works, what does not, and what is needed. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:194–207. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fleuren JF, Voerman GE, Erren-Wolters CV, Snoek GJ, Rietman JS, Hermens HJ, et al. Stop using the Ashworth Scale for the assessment of spasticity. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:46–52. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.177071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Malhotra S, Pandyan AD, Day CR, Jones PW, Hermens H. Spasticity, an impairment that is poorly defined and poorly measured. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:651–8. doi: 10.1177/0269215508101747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hobart JC, Riazi A, Thompson AJ, Styles IM, Ingram W, Vickery PJ, et al. Getting the measure of spasticity in multiple sclerosis: The Multiple Sclerosis Spasticity Scale (MSSS-88) Brain. 2006;129:224–34. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pozzilli C. Advances in the management of multiple sclerosis spasticity: Experiences from recent studies and everyday clinical practice. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13:49–54. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2013.865877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wissel J, Ward AB, Erztgaard P, Bensmail D, Hecht MJ, Lejeune TM, et al. European consensus table on the use of botulinum toxin type A in adult spasticity. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:13–25. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flachenecker P, Henze T, Zettl UK. Nabiximols (THC/CBD oromucosal spray, Sativex(R)) in clinical practice--results of a multicenter, non-interventional study (MOVE 2) in patients with multiple sclerosis spasticity. Eur Neurol. 2014;71:271–9. doi: 10.1159/000357427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gironi M, Martinelli-Boneschi F, Sacerdote P, Solaro C, Zaffaroni M, Cavarretta R, et al. A pilot trial of low-dose naltrexone in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2008;14:1076–83. doi: 10.1177/1352458508095828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stevenson VL. Intrathecal baclofen in multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol. 2014;72:32–4. doi: 10.1159/000367623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pearson M, Dieberg G, Smart N. Exercise as a Therapy for Improvement of Walking Ability in Adults With Multiple Sclerosis: A Meta-Analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goodman AD, Brown TR, Schapiro RT, Klingler M, Cohen R, Blight AR. A pooled analysis of two phase 3 clinical trials of dalfampridine in patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2014;16:153–60. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2013-023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stein RB, Everaert DG, Thompson AK, Chong SL, Whittaker M, Robertson J, et al. Long-term therapeutic and orthotic effects of a foot drop stimulator on walking performance in progressive and nonprogressive neurological disorders. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24:152–67. doi: 10.1177/1545968309347681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.de Seze M, Ruffion A, Denys P, Joseph PA, Perrouin-Verbe B, GENULF The neurogenic bladder in multiple sclerosis: Review of the literature and proposal of management guidelines. Mult Scler. 2007;13:915–28. doi: 10.1177/1352458506075651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lucio AC, Perissinoto MC, Natalin RA, Prudente A, Damasceno BP, D’ancona CA. A comparative study of pelvic floor muscle training in women with multiple sclerosis: Its impact on lower urinary tract symptoms and quality of life. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:1563–8. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000900010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ferreira AP, Pegorare AB, Salgado PR, Casafus FS, Christofoletti G. Impact of a Pelvic Floor Training Program Among Women with Multiple Sclerosis: A Controlled Clinical Trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2015 doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fowler CJ. Systematic review of therapy for neurogenic detrusor overactivity. Can Urol Assoc J. 2011;5:S146–8. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.11187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maman K, Aballea S, Nazir J, Desroziers K, Neine ME, Siddiqui E, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of medical treatments for the management of overactive bladder: A systematic literature review and mixed treatment comparison. Eur Urol. 2014;65:755–65. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bosma R, Wynia K, Havlikova E, De Keyser J, Middel B. Efficacy of desmopressin in patients with multiple sclerosis suffering from bladder dysfunction: A meta-analysis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2005;112:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2005.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cox L, Cameron AP. OnabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of overactive bladder. Res Rep Urol. 2014;6:79–89. doi: 10.2147/RRU.S43125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Prasad RS, Smith SJ, Wright H. Lower abdominal pressure versus external bladder stimulation to aid bladder emptying in multiple sclerosis: A randomized controlled study. Clin Rehabil. 2003;17:42–7. doi: 10.1191/0269215503cr583oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nusrat S, Gulick E, Levinthal D, Bielefeldt K. Anorectal dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. ISRN Neurol 2012. 2012 doi: 10.5402/2012/376023. 376023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hinds JP, Eidelman BH, Wald A. Prevalence of bowel dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. A population survey. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1538–42. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91087-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Preziosi G, Raptis DA, Storrie J, Raeburn A, Fowler CJ, Emmanuel A. Bowel biofeedback treatment in patients with multiple sclerosis and bowel symptoms. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1114–21. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318223fd7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Preziosi G, Gosling J, Raeburn A, Storrie J, Panicker J, Emmanuel A. Transanal irrigation for bowel symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:1066–73. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182653bd1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maeda Y, O’Connell PR, Lehur PA, Matzel KE, Laurberg S European SNS Bowel Study Group. Sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence and constipation: A European consensus statement. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:O74–87. doi: 10.1111/codi.12905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kessler TM, Fowler CJ, Panicker JN. Sexual dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:341–50. doi: 10.1586/14737175.9.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cordeau D, Courtois F. Sexual disorders in women with MS: Assessment and management. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014;57:337–47. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Previnaire JG, Lecourt G, Soler JM, Denys P. Sexual disorders in men with multiple sclerosis: Evaluation and management. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014;57:329–36. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dachille G, Ludovico GM, Pagliarulo G, Vestita G. Sexual dysfunctions in multiple sclerosis. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2008;60:77–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]