Abstract

We describe a case of pediatric neuromyelitis optica (NMO) with muscle and lung involvement in addition to central nervous system disease. Our patient initially presented with features of area postrema syndrome, then subsequently with optic neuritis. The patient also had recurrent hyperCKemia that responded to corticosteroids. Finally, axillary and hilar adenopathy with pulmonary consolidation were noted as well and responded to immunomodulation. Our case highlights multisystem involvement in NMO including non-infectious pulmonary findings which have not been described in the pediatric population previously.

Keywords: Adenopathy, hyperCKemia, lung consolidation, neuromyelitis optica, NMO

Case Report

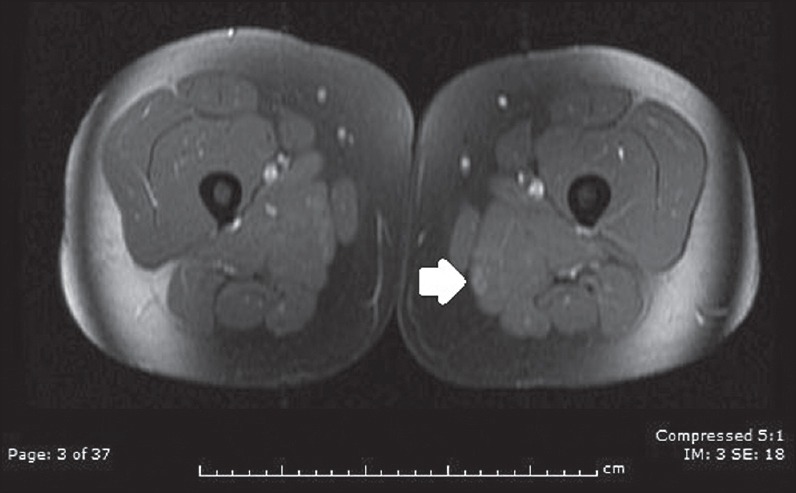

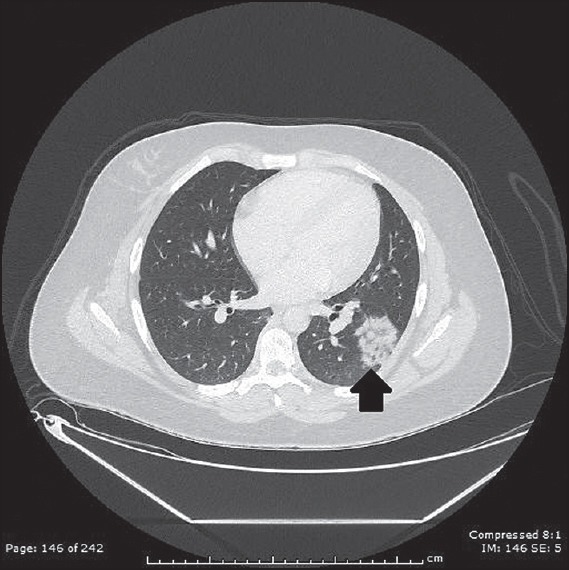

A 13-year-old girl initially presented with nausea and intractable vomiting for several weeks associated with unintentional weight loss of about 22 pounds. She subsequently developed cranial nerve palsies and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed T2 hyperintensity in the right medulla extending to the cervicomedullarly junction as well as in the anterior medial temporal lobe [Figure 1]. She had elevation of multiple muscle inflammatory markers; creatine kinase (CK) to 5,018, lactate dehydrogenace (LDH) to 1000, and aldolase to 23. She was given methylprednisolone pulse and intravenous immunoglobulin. She showed overall clinical improvement and CK level normalized. She was readmitted 4 months later with blindness due to left-sided optic neuritis. Her CK was now elevated to 8,216. MRI of femur showed patchy T2 hyperintensities and enhancement within the peripheral right and left biceps femoris muscle and left adductor magnus muscle suggestive of myositis [Figure 2]. She had a chest X-ray that showed left lower lobe consolidation and hilar adenopathy. Computed tomography scan of the chest confirmed left lower lobe consolidation [Figure 3] and left hilar adenopathy plus showed bilateral axillary adenopathy. Tuberculosis and other infections were ruled out after extensive investigations and consultation with infectious disease specialists. Extensive rheumatological investigations including antinuclear antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-Sjogren's syndrome antibodies A and B, complement levels were all negative. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid angiotensin-converting enzymes were normal. Rheumatological diseases were considered unlikely after consultation with pediatric rheumatologists. Antibodies to aquaporin-4 (AQP-4) were positive in the serum but negative in cerebrospinal fluid. She was treated with methylprednisolone pulse followed by rituximab with a second cycle about 6 months later. Her CK level normalized quickly, vision showed slow improvement to 20/80 and a chest X-ray subsequently normalized. Antibodies to AQP-4 were reconfirmed several months later to be positive. She has remained stable overall for almost 1 year since the episode of optic neuritis.

Figure 1.

T2 hyperintensity in medulla of our patient who initially had features of area postrema syndrome

Figure 2.

Abnormal area of enhancement in left adductor magnus muscle during an episode of hyperCKemia

Figure 3.

Left lower lobe consolidation

Discussion

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) was first recognized as a distinct clinical entity in the nineteenth century.[1] Subsequently, Devic and his student Gault used the term “neuromyelitis optica” for the first time.[2,3] Since then, there have been significant advances in our understanding of this condition especially with the availability of the highly specific testing for the AQP-4 antibodies in 2004.[4] Previously, absence of disease other than in the optic nerves and the spinal cord was considered necessary for a diagnosis of NMO. However, revised diagnostic criteria in 2006 concluded that involvement of the central nervous system beyond the optic nerves and spinal cord was compatible with NMO.[5] Those criteria were further revised this year and include recognized core features of NMO spectrum disorders (NMOSD): Optic neuritis, myelitis, area postrema syndrome (nausea, vomiting, and hiccups), diencephalic syndrome, and other brainstem and cerebral syndromes. The expansion of the criteria are aimed at facilitating diagnosis in seronegative patients with corresponding MRI abnormalities with dissemination in time as well as optic neuritis, myelitis, or area postrema syndrome plus another core feature.[6]

AQPs are water channels and are expressed in highest concentration in opticospinal tissue. Development of optic nerve and spinal cord lesions in NMO and NMOSD is thought to be secondary to complement activation by antibodies to AQP-4, resulting in perivascular immune complex deposition and astrocyte injury. AQPs are also expressed in tissues throughout the body in addition to the central nervous system including in various epithelia and endothelia involved in fluid transport, as well as in other cell types such as epidermis, adipocytes, and skeletal muscle.[7] They are also expressed in lung and airways.[8] In recent years, clinical involvement of tissues other than the central nervous system is increasingly recognized with NMO and NMOSD. Various cases of transient hyperCKemia have been reported in recent years suggesting active muscle disease in NMO.[9,10,11,12,13,14,15] Inflammatory changes have been reported in some of these patients. Reduced AQP-4 expression and deposition of activated complement has been noted and complement-mediated sarcolemmal injury is hypothesized to be the reason for hyperCKemia.[12,15]

Non-infectious lung involvement in NMO has been described in a single case report previously with lung infiltrate and adenopathy.[16] Biopsy of a lymph node in this 50-year-old patient revealed non-caseating granuloma and the authors suspected co-existence of sarcoidosis with NMO. There is significant interest in co-occurrence and overlap of rheumatological disease, NMO, and sarcoidosis and in fact all of these are often considered to be on a single spectrum of disorders.[17,18] The limitation of this case is that we did not perform a biopsy in our patient because of relatively quick resolution with corticosteroids and immunomodulation. It is possible that our patient may have had co-existent sarcoidosis. However, our case highlights multisystem involvement in pediatric NMO, NMOSD, and overlap with other related disorders like sarcoidosis. Pulmonary involvement in NMO and NMOSD is supported by the fact that AQPs are also expressed in lung and airways.

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to thank Dr. Skorn Ponrartana for providing help with figures.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Jarius S, Wildemann B. On the contribution of Thomas Clifford Allbutt, F.R.S, to the early history of neuromyelitis optica. J Neurol. 2013;260:100–4. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6594-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gault F. The neuromyelitis optica. Thesis presented to Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy in Lyon. 1894 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devic E. Myelitesubaiguecompliquee de neuriteoptique. Bull Med. 1894;8:1033–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lennon VA, Wingerchuk DM, Kryzer TJ. A serum autoantibody marker of neuromyelitis optica: Distinction from multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2004;364:2106–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17551-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG. Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2006;66:1485–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000216139.44259.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wingerchuk D, Banwell B, Bennett J, Cabre P, Carroll W, Chitnis T, et al. Revised Diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology. 2014;82:10. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verkman AS. Aquaporins in clinical medicine. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:303–16. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-043010-193843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verkman AS. Role of aquaporins in lung liquid physiology. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;159:324–30. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki N, Takahashi T, Aoki M, Misu T, Konohana S, Okumura T, et al. Neuromyelitis optica preceded by hyperCKemia episode. Neurology. 2010;74:1543–5. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181dd445b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deguchi S, Deguchi K, Sato K, Yunoki T, Omote Y, Morimoto N, et al. HyperCKemia related to the initial and recurrent attacks of neuromyelitis optica. Intern Med. 2012;51:2617–20. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okada H, Wada M, Sato H, Yamaguchi Y, Tanji H, Kurokawa K, et al. Neuromyelitisoptica preceded by hyperCKemia and a possible association with coxsackie virus group A10 infection. Intern Med. 2013;52:2665–8. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malik R, Lewis A, Cree BA, Ratelade J, Rossi A, Verkman AS, et al. Transient hyperCKemia in the setting of neuromyelitisoptica (NMO) Muscle Nerve. 2014;50:859–62. doi: 10.1002/mus.24298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Filippo M, Franciotta D, Massa R, Di Gregorio M, Zardini E, Gastaldi M, et al. Recurrent hyperCKemia with normal muscle biopsy in a pediatric patient with neuromyelitisoptica. Neurology. 2012;79:1182–4. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182698d39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokoyama N, Niino M, Takahashi T, Matsushima M, Maruo Y. Seroconversion of neuromyelitisoptica spectrum disorder with hyperCKemia: A case report. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:e143. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo Y, Lennon VA, Popescu BF, Grouse CK, Topel J, Milone M, et al. Autoimmune Aquaporin-4 Myopathy in Neuromyelitis optica spectrum. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:1025–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawaya R, Radwan W. Sarcoidosis associated with neuromyelitis optica. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20:1156–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wingerchuk DM, Weinshenker BG. The emerging relationship between neuromyelitis optica and systemic rheumatologic autoimmune disease. Mult Scler. 2012;18:5–10. doi: 10.1177/1352458511431077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enzenauer RJ, West SG. Sarcoidosis in autoimmune disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1992;22:1–17. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(92)90043-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]