Abstract

Objectives. We evaluated HIV testing and service delivery in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)–funded sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics.

Methods. We assessed HIV testing, HIV positivity, receipt of HIV test results, linkage to medical care, and referral services from 61 health department jurisdictions from 2011 to 2013.

Results. In 2013, 18.6% (621 010) of all CDC-funded HIV-testing events were conducted in STD clinics, and 0.8% were newly identified as HIV-positive. In addition, 27.3% of all newly identified HIV-positive persons and 30.1% of all newly identified HIV-positive men who have sex with men were identified in STD clinics. Linkage to care within any time frame was 63.8%, and linkage within 90 days was 55.3%. Although there was a decrease in first-time HIV testers in STD clinics from 2011 to 2013, identification of new positives increased.

Conclusions. Although linkage to care and referral to partner services could be improved, STD clinics appear successful at serving populations disproportionately affected by HIV. These clinics may reach persons who may not otherwise seek HIV testing or medical services and provide an avenue for service provision to these populations.

More than 1.2 million people are living with HIV in the United States, and approximately 14% are not diagnosed.1,2 Although HIV incidence has remained stable over the past several years, some groups are disproportionately affected by HIV, particularly gay men, bisexual men, and other men who have sex with men (collectively referred to as MSM) as well as racial/ethnic minority populations, specifically Blacks or African Americans (hereinafter referred to as African Americans) and Hispanics or Latinos.3,4 Men who have sex with men account for approximately 2% of the US population.5,6 However, they accounted for 63% of all new HIV infections in 2010 and 54% of people living with HIV in 2011.1,3 In addition, although African Americans account for 12% of the US population, they accounted for 44% of all new HIV infections in 2010 and 41% of people living with HIV in 2011.1,3 In 2013, the rate of HIV diagnoses was 55.9 (per 100 000) for African Americans, in comparison with 18.7 for Hispanics or Latinos and 6.6 for Whites.7 Finally, Hispanics or Latinos account for approximately 17% of the US population,8 but accounted for 21% of new HIV infections in 2010 and 20% of people living with HIV in 2011.1,3

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends routine HIV screening in health care settings, including sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics, for clients aged 13 to 64 years where prevalence is 0.1% or more.9 HIV testing and knowledge of HIV status are the first steps along the HIV continuum of care and serve as an important entry point to prevention services and linkage to HIV medical care. Previous research has indicated that early initiation of antiretroviral therapy has substantial medical benefits to HIV-positive individuals and prevention benefits to their HIV-negative partners by reducing transmission by up to 96%.10,11 The National HIV/AIDS Strategy12 has also emphasized the importance of knowledge of HIV status, reducing health-related disparities, and treatment as prevention, particularly increasing access to HIV medical care and strengthening linkage and retention in care. In light of the national priorities to reduce new HIV infections, it is important to gain a better understanding of HIV testing programs and service delivery to populations who may be at high risk for HIV infection.

Sexually transmitted disease clinics often serve minority populations and persons who may be economically disadvantaged, have limited access to health care, and have comorbid physical and medical concerns.13,14 As reflected by high coinfection rates between HIV and several STDs,15 STD clinics often reach clients who are at high risk for HIV infection and who may be unaware of their HIV status.13,16,17 In addition, they are more likely to reach clients who are younger, male, African American, and heterosexual persons who are at high risk for HIV infection, as well as MSM.13,18–20 Previous studies have indicated that STD clinics report a higher frequency of HIV testing than other health care settings and are more likely to identify persons who are HIV-positive.13,20,21

The STD clinics provide essential sexual health services to clients who may not otherwise have access to health care services but are at high risk for HIV infection. We evaluated HIV testing and HIV service delivery among CDC-funded STD clinics in 2013. To our knowledge, this is one of the first articles to present national-level program data from STD clinics on HIV testing and HIV service delivery. Our aims were to assess

HIV testing, including first-time testers;

identification of newly diagnosed HIV-positive persons;

linkage to HIV medical care;

referral and interview for partner services; and

referral to HIV prevention services.

In addition, we compared the proportion of HIV testing and identification of new HIV-positive persons that occurred in STD clinics with national data from all CDC-funded sites. Finally, we examined the demographic characteristics of the populations who received HIV services in STD clinics and the differences in HIV testing and HIV service delivery in CDC-funded STD clinics from 2011 to 2013.

METHODS

The CDC funds state and local health departments to provide HIV testing and prevention services, and data are collected as part of CDC’s National HIV Prevention Program Monitoring and Evaluation (NHM&E). In 2011, CDC funded 59 health department jurisdictions for HIV testing, and in 2012 and 2013 funded 61 for this activity. Data for each CDC-funded HIV testing event are collected by local service providers and submitted to CDC biannually without personal identifiers via a secure, online CDC-provided system. The CDC uses these data for monitoring and evaluation of HIV testing and HIV-related service delivery.

For analyses of 2013 data, we included only HIV testing events and the corresponding data on HIV service delivery in STD clinics from the 61 health department jurisdictions submitted to CDC by June 2, 2014. For analyses on HIV testing and service delivery from 2011 to 2013, we included data from all jurisdictions submitting complete, test-level data for each year. We defined an STD clinic as a health care facility that specializes in sexual health and in the prevention and treatment of STDs.

Measures

Demographics.

For each test event, we collected self-reported data on gender, race/ethnicity, and age. In terms of select target populations, we categorized male clients who reported male-to-male sexual contact in the past 12 months as MSM. We categorized clients as transgender if their self-reported current gender was different from their self-reported gender at birth. Finally, heterosexual male clients were defined as male clients who only reported heterosexual contact with a female partner in the past 12 months, and heterosexual female clients were female clients who only reported heterosexual contact with a male partner in the past 12 months. The CDC requires the collection of risk behavior data to calculate target populations for all HIV-testing events in non–health care settings (e.g., HIV counseling and testing sites, community-based organizations) and only for HIV-positive testing events in health care settings. However, some jurisdictions provided risk behavior data for HIV-negative testing events conducted in health care settings, and we have included these data in analyses. In STD clinics, data for 369 250 testing events were either required for target populations or available for HIV-negative testing events. Other target populations (e.g., injection drug users), HIV-positive persons who did not report injection drug use or sexual behavior in the past 12 months, or missing data that are not presented in this article comprise 7541 of the 369 250 testing events among target populations in STD clinics.

HIV testing events.

We defined HIV testing events as all records submitted to the National HIV Prevention Program Monitoring and Evaluation online data system, for which a test technology (conventional, rapid, nucleic acid amplification RNA testing, or other) or test result (positive, negative, indeterminate, or invalid) was reported. We defined first-time testers as HIV testing events among clients who did not report having a previous HIV test. Newly identified HIV-positive persons were those who tested HIV-positive during the current test event but did not self-report a previous HIV test or a previous HIV-positive test result.

Linkage to HIV medical care.

We defined linkage as attendance at first medical appointment for clients who tested HIV-positive. We examined linkage for all newly identified HIV-positive persons. The National HIV/AIDS Strategy12 has a goal for 2015 that 85% of persons newly diagnosed with HIV are linked to HIV medical care within 90 days of diagnosis. Therefore, we assessed and analyzed linkage within 90 days and linkage within any time frame (which includes linkage within 90 days and greater than 90 days).

Referral and interview for partner services.

Partner services are a set of confidential, voluntary services to help persons with HIV notify their sexual and drug-injection partners of possible HIV exposure, to offer services that can protect the health of partners, and to prevent STD reinfection.22 We considered clients who were either referred to or interviewed for partner services “referred.” We considered clients who were asked and provided information for partner services “interviewed.” We examined referral and interview for partner services for all newly identified HIV-positive persons.

Referral to HIV prevention services.

We defined HIV prevention services as any service or intervention directly aimed at reducing risk for transmitting or acquiring HIV infection (e.g., prevention counseling, behavioral interventions, risk-reduction counseling).23 It excludes HIV posttest counseling and indirect services such as mental health services or housing. We examined referral to HIV prevention services for all newly identified HIV-positive persons.

Data Analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics to examine the frequency of HIV testing and other HIV service delivery in STD clinics by client characteristics. Denominators are included in tables for clarity and ease of interpretation.

We conducted χ2 analyses to examine change in percentage of newly identified HIV-positive persons and linkage to HIV medical care in STD clinics from 2011 to 2013. We only examined linkage to HIV medical care within 90 days from 2012 to 2013, as this variable was not required by CDC in 2011. We performed all statistical analyses in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

In 2013, 3 343 633 CDC-funded HIV testing events were conducted in the United States. Sexually transmitted disease clinics accounted for 18.6% (621 010) of all CDC-funded HIV testing events (Table 1). The STD clinics accounted for 22.7% of testing events among all persons aged 20 to 29 years, 20.9% among all African Americans, approximately 17.0% among all MSM and all African American MSM, 28.1% among all African American heterosexual male clients, 21.4% among all Hispanic or Latino male clients, and 20.6% among all African American heterosexual female clients. Of all HIV first-time testers, 17.2% were identified in STD clinics in 2013. Also, 20.8% of all first-time testers aged 20 to 29 years, 17.6% of all African American MSM first-time testers, 27.2% of all African American heterosexual male first-time testers, 20% of all Hispanic or Latino male first-time testers, and 20.1% of all African American heterosexual female first-time testers were identified in STD clinics (Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Proportion of HIV Testing Events, First-Time Testers, and Newly Identified HIV-Positive Persons in US Sexually Transmitted Disease Clinics by Client Characteristics Compared With All Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–Funded HIV Testing Events in the United States, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands: 2013

| HIV Testing Events |

First-Time Testers |

Newly Identified HIV-Positive Persons |

||||

| Client Characteristics | All CDC-Funded, No. | In STD Clinics, No. (Row %) | All CDC-Funded, No. | In STD Clinics, No. (Row %) | All CDC-Funded, No. | In STD Clinics, No. (Row %) |

| Age groups, y | ||||||

| 13–19 | 279 412 | 55 520 (19.9) | 108 160 | 19 261 (17.8) | 579 | 143 (24.7) |

| 20–29 | 1 358 687 | 308 778 (22.7) | 267 788 | 55 770 (20.8) | 6 895 | 2 061 (29.9) |

| 30–39 | 756 782 | 141 127 (18.6) | 106 817 | 17 241 (16.1) | 4 118 | 1 148 (27.9) |

| 40–49 | 461 696 | 66 645 (14.4) | 69 986 | 8 790 (12.6) | 3 056 | 698 (22.8) |

| ≥ 50 | 456 169 | 46 934 (10.3) | 80 813 | 8 289 (10.3) | 2 434 | 496 (20.4) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 901 973 | 178 528 (19.8) | 207 390 | 41 765 (20.1) | 3 445 | 935 (27.1) |

| Black or African American | 1 506 016 | 314 687 (20.9) | 235 658 | 42 722 (18.1) | 9 571 | 2 624 (27.4) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 713 058 | 93 010 (13.0) | 152 200 | 18 809 (12.4) | 3 407 | 926 (27.2) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1 632 645 | 324 133 (19.9) | 332 697 | 64 723 (19.5) | 13 976 | 4 007 (28.7) |

| Female | 1 687 367 | 293 081 (17.4) | 302 050 | 44 656 (14.8) | 3 188 | 732 (23.0) |

| Target populationsa | ||||||

| MSM | 252 751 | 42 413 (16.8) | 34 609 | 5 712 (16.5) | 7 896 | 2 373 (30.1) |

| Black or African American MSM | 62 764 | 10 360 (16.5) | 9 135 | 1 612 (17.6) | 3 570 | 1 087 (30.4) |

| Hispanic or Latino MSM | 59 797 | 9 799 (16.4) | 8 737 | 1 144 (13.1) | 1 814 | 551 (30.4) |

| Transgender | 11 047 | 1 389 (12.6) | 1 791 | 263 (14.7) | 209 | 24 (11.5) |

| Heterosexual male | 571 333 | 153 552 (26.9) | 167 232 | 43 065 (25.8) | 2 505 | 694 (27.7) |

| Black or African American heterosexual male | 299 277 | 84 025 (28.1) | 66 101 | 17 953 (27.2) | 1 793 | 499 (27.8) |

| Hispanic or Latino heterosexual male | 104 187 | 22 296 (21.4) | 37 236 | 7 448 (20.0) | 375 | 106 (28.3) |

| Heterosexual female | 829 779 | 164 355 (19.8) | 177 601 | 33 100 (18.6) | 2 147 | 571 (26.6) |

| Black or African American heterosexual female | 408 137 | 83 926 (20.6) | 63 727 | 12 811 (20.1) | 1 508 | 405 (26.9) |

| Hispanic or Latina heterosexual female | 163 478 | 26 002 (15.9) | 40 677 | 5 473 (13.5) | 277 | 72 (26.0) |

| Total | 3 343 633 | 621 010 (18.6) | 638 054 | 109 966 (17.2) | 17 426 | 4 766 (27.3) |

Note. CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; MSM = men who have sex with men; STD = sexually transmitted disease. Percentages may not total to 100% because select categories are shown for descriptives.

Data to identify target populations are required for all testing events conducted in non–health care settings but are only required for HIV-positive persons from health care settings. However, some jurisdictions submitted data on HIV-negative persons from health care settings and those data are reflected in the numbers for HIV-testing events and first-time testers.

Of the 621 010 HIV testing events conducted in STD clinics, approximately half were among persons aged 20 to 29 years (49.7%) and African Americans (50.7%). More male clients (52.2%) were tested than female clients (47.2%). Of the 369 250 HIV-testing events in STD clinics among target populations, heterosexual female clients accounted for 44.5% of testing events, and 22.7% were among African American heterosexual female clients. Heterosexual male clients accounted for 41.6% of these testing events, and 22.8% were among African American heterosexual male clients. Finally, MSM and transgender persons accounted for 11.5% and 0.4%, respectively, of testing events conducted in STD clinics (Table 2).

TABLE 2—

HIV Testing Events, First-Time Testers, Newly Identified HIV-Positive Persons, and HIV Service Delivery Among Newly Identified HIV-Positive Persons in US Sexually Transmitted Disease Clinics by Client Characteristics: 2013

| Client Characteristics | HIV Testing Events, No. (Column %) | First-Time Testers, No. (Row %) | Newly Identified HIV-Positive Persons, No. (Row %) | Linked to HIV Medical Care Within Any Time Frame No. (Row %) | Linked to HIV Medical Care in 90 Days, No. (Row %) | Referred to HIV Partner Services, No. (Row %) | Interviewed for HIV Partner Services, No. (Row %) | Referred to HIV Prevention Services, No. (Row %) |

| Age groups, y | ||||||||

| 13–19 | 55 520 (8.9) | 19 261 (34.7) | 143 (0.3) | 84 (58.7) | 71 (49.7) | 102 (71.3) | 83 (58.0) | 96 (67.1) |

| 20–29 | 308 778 (49.7) | 55 770 (18.1) | 2 061 (0.7) | 1 302 (63.2) | 1 101 (53.4) | 1 532 (74.3) | 1 295 (62.8) | 1 388 (67.3) |

| 30–39 | 141 127 (22.7) | 17 241 (12.2) | 1 148 (0.8) | 737 (64.2) | 637 (55.5) | 814 (70.9) | 675 (58.8) | 715 (62.3) |

| 40–49 | 66 645 (10.7) | 8 790 (13.2) | 698 (1.0) | 444 (63.6) | 396 (56.7) | 490 (70.2) | 424 (60.7) | 446 (63.9) |

| ≥ 50 | 46 934 (7.6) | 8 289 (17.7) | 496 (1.1) | 328 (66.1) | 284 (57.3) | 354 (71.4) | 307 (61.9) | 332 (66.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 178 528 (28.7) | 41 765 (23.4) | 935 (0.5) | 660 (70.6) | 554 (59.3) | 717 (76.7) | 604 (64.6) | 625 (66.8) |

| Black or African American | 314 687 (50.7) | 42 722 (13.6) | 2 624 (0.8) | 1 431 (54.5) | 1 234 (47.0) | 1 735 (66.1) | 1 438 (54.8) | 1 636 (62.3) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 93 010 (15.0) | 18 809 (20.2) | 926 (1.0) | 750 (81.0) | 664 (71.7) | 818 (88.3) | 722 (78.0) | 709 (76.6) |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 324 133 (52.2) | 64 723 (20.0) | 4 007 (1.2) | 2 588 (64.6) | 2 215 (55.3) | 2 994 (74.7) | 2 520 (62.9) | 2 697 (67.3) |

| Female | 293 081 (47.2) | 44 656 (15.2) | 732 (0.2) | 435 (59.4) | 401 (54.8) | 487 (66.5) | 424 (57.9) | 472 (64.5) |

| Target populationsa | ||||||||

| MSM | 42 413 (11.5) | 5 712 (13.5) | 2 373 (5.6) | 1 724 (72.7) | 1 593 (67.1) | 2 090 (88.1) | 1 774 (74.8) | 1 869 (78.8) |

| Black or African American MSM | 10 360 (2.8) | 1 612 (15.6) | 1 087 (10.5) | 714 (65.7) | 657 (60.4) | 903 (83.1) | 768 (70.7) | 855 (78.7) |

| Hispanic or Latino MSM | 9 799 (2.7) | 1 144 (11.7) | 551 (5.6) | 448 (81.3) | 411 (74.6) | 529 (96.0) | 452 (82.0) | 446 (80.9) |

| Transgender | 1 389 (0.4) | 263 (18.9) | 24 (1.7) | 18 (75.0) | 18 (75.0) | 20 (83.3) | 18 (75.0) | 19 (79.2) |

| Heterosexual male | 153 552 (41.6) | 43 065 (28.0) | 694 (0.5) | 393 (56.6) | 340 (49.0) | 497 (71.6) | 413 (59.5) | 446 (64.3) |

| Black or African American heterosexual male | 84 025 (22.8) | 17 953 (21.4) | 499 (0.6) | 242 (48.5) | 199 (39.9) | 328 (65.7) | 263 (52.7) | 292 (58.5) |

| Hispanic or Latino heterosexual male | 22 296 (6.0) | 7 448 (33.4) | 106 (0.5) | 92 (86.8) | 89 (84.0) | 99 (93.4) | 90 (84.9) | 84 (79.2) |

| Heterosexual female | 164 355 (44.5) | 33 100 (20.1) | 571 (0.3) | 360 (63.0) | 331 (58.0) | 414 (72.5) | 354 (62.0) | 400 (70.1) |

| Black or African American heterosexual female | 83 926 (22.7) | 12 811 (15.3) | 405 (0.5) | 244 (60.2) | 217 (53.6) | 273 (67.4) | 227 (56.0) | 265 (65.4) |

| Hispanic/Latina heterosexual female | 26 002 (7.0) | 5 473 (21.0) | 72 (0.3) | 63 (87.5) | 62 (86.1) | 68 (94.4) | 64 (88.9) | 64 (88.9) |

| Total | 621 010 (100) | 109 966 (17.7) | 4 766 (0.8) | 3 043 (63.8) | 2 636 (55.3) | 3 504 (73.5) | 2 965 (62.2) | 3 189 (66.9) |

Note. MSM = men who have sex with men. Percentages may not total to 100% because select categories are shown for descriptives.

Data to identify target populations are required for all testing events conducted in non–health care settings but are only required for HIV-positive persons from health care settings. However, some jurisdictions may submit data on HIV-negative persons from health care settings and those data are reflected in the numbers for HIV-testing events and first-time testers. Therefore, for testing events in sexually transmitted disease clinics among target populations, the denominator for the column percentages is 369 250. Other target populations (e.g., injection drug users), HIV-positive persons who did not report injection drug use or sexual behavior in the past 12 months, or missing data that are not presented in this article account for 7541 of the 369 250 testing events among target populations in sexually transmitted disease clinics.

We found a higher percentage of first-time HIV testers among persons aged 13 to 19 years (34.7%), Hispanic or Latino heterosexual male clients (33.4%), and all heterosexual male clients (28.0%). There also was a higher percentage of first-time testers among male clients (20.0%) than female clients (15.2%). Among target populations, 15.6% of African American MSM tested in STD clinics were first-time testers, followed by 13.5% of all MSM, and 11.7% of Hispanic or Latino MSM. Approximately 19% of transgender persons were first-time testers. Finally, 21.0% of Hispanic or Latino heterosexual female clients in STD clinics were first-time testers, followed by 20.1% of all heterosexual female clients, and 15.3% of African American heterosexual female clients (Table 2).

Newly Identified HIV-Positive Persons

Newly identified HIV-positive persons (17 426) accounted for 0.5% of all CDC-funded testing events in 2013, and 27.3% (4766) of all these persons were identified in STD clinics in 2013. The STD clinics accounted for 29.9% of newly identified HIV-positive persons among all persons aged 20 to 29 years and approximately 27% each among Whites, African Americans, and Hispanics or Latinos. Also, 28.7% of the newly identified HIV-positive male clients and 23.0% of the female clients were found in STD clinics. Finally, almost 30.0% of the newly identified HIV-positive persons among all African American and Hispanic or Latino MSM and all MSM overall, approximately 28.0% among all African American and Hispanic or Latino heterosexual male clients and all heterosexual male clients overall, and approximately 27.0% of African American and Hispanic or Latino heterosexual female clients and all heterosexual female clients overall were found in STD clinics (Table 1).

In 2013, the HIV-positivity percentage among newly identified HIV-positive persons was 0.8% in STD clinics. The highest percentage of newly identified HIV-positive persons was identified among African American MSM (10.5%), Hispanic or Latino and all MSM overall (5.6%), and transgender persons (1.7%). In addition, 1.0% of persons aged 40 to 49 years and 1.1% of persons aged 50 years and older were newly identified as HIV-positive; 1.0% of Hispanics or Latinos were newly identified as HIV-positive compared with 0.8% of African Americans. Finally, 1.2% of male clients were newly identified HIV-positive persons in STD clinics compared with 0.2% of female clients. Of the 4766 newly identified HIV-positive persons in STD clinics, 84% (n = 4007) were male clients, 55.1% (n = 2624) were African Americans, 49.8% (n = 2373) were MSM, and 43.2% (n = 2061) were persons aged 20 to 29 years (Table 2).

Linkage to HIV Medical Care and Referral Services

Among the 4766 newly identified HIV-positive persons identified in STD clinics, 63.8% were linked to HIV medical care within any time frame following their HIV-positive diagnosis. Linkage within any time frame was generally comparable across age and gender. However, African Americans (54.5%) were linked within any time frame less frequently than Whites (70.6%) and Hispanics or Latinos (81.0%). In addition, heterosexual male clients (56.6%) were linked less than MSM (72.7%) and transgender persons (75.0%). Among newly identified HIV-positive persons, 55.3% were linked to HIV medical care within 90 days. Linkage within 90 days was generally comparable across age and gender. However, African Americans (47.0%) were linked within 90 days less frequently than Whites (59.3%) and Hispanics or Latinos (71.7%). In addition, heterosexual male clients (49.0%) and heterosexual female clients (58.0%) were linked less often than MSM (67.1%) and transgender persons (75.0%; Table 2).

Almost three quarters (73.5%) of newly identified HIV-positive individuals were referred to HIV partner services. Referral percentages were generally comparable across age and gender. African Americans (66.1%) were referred to partner services less often than Whites (76.7%) and Hispanics or Latinos (88.3%). Heterosexual male clients (71.6%) and heterosexual female clients (72.5%) were referred less often than MSM (88.1%) and transgender persons (83.3%). However, referral for Hispanic or Latino heterosexual male and female clients was approximately 94.0%. Among those newly identified as HIV-positive, 62.2% were interviewed for HIV partner services (84.6% of those referred), and interview percentages were similar across age and gender. African Americans (54.8%) were interviewed for partner services less often than were Whites (64.6%) and Hispanics or Latinos (78.0%). Heterosexual male clients (59.5%) and heterosexual female clients (62%) were interviewed less often than MSM (74.8%) and transgender persons (75.0%). However, interview percentages for Hispanic or Latino heterosexual male and female clients were 84.9% and 88.9%, respectively (Table 2).

Finally, 66.9% of newly identified HIV-positive persons were referred to HIV-prevention services, and referral percentages were similar across age and gender. Whites (66.8%) and African Americans (62.3%) were referred less often than Hispanics or Latinos (76.6%). Heterosexual male clients (64.3%) and heterosexual female clients (70.1%) were referred less often than MSM (78.8%) and transgender persons (79.2%). However, referral percentages for Hispanic or Latino heterosexual male and female clients were 79.2% and 88.9%, respectively (Table 2).

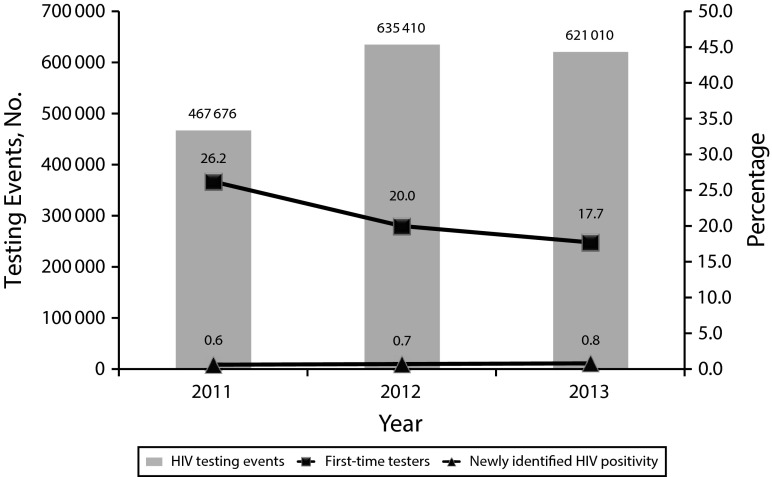

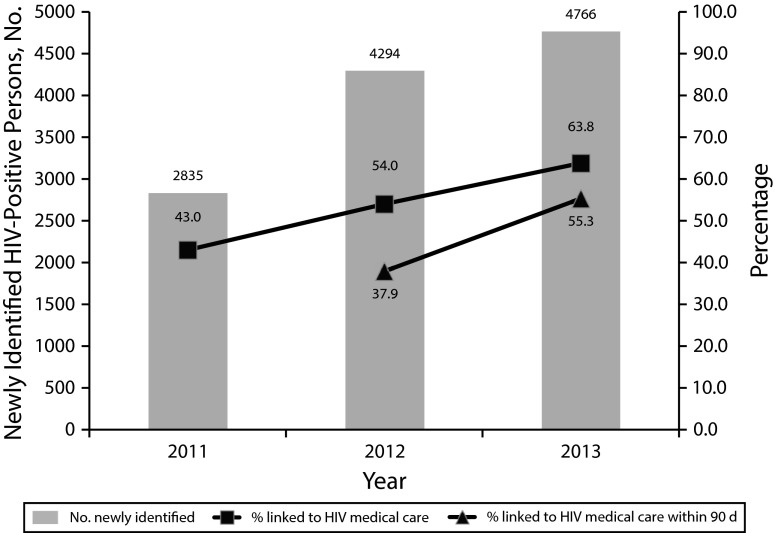

From 2011 to 2013, there was an increase in the number of CDC-funded HIV testing events conducted in STD clinics from 2011 (467 676) to 2013 (621 010) but a slight decrease from 2012 (635 410) to 2013 (621 010). The χ2 analyses revealed that the percentage of first-time HIV testers in STD clinics significantly decreased each year (P < .01). However, the percentage of newly identified HIV-positive persons significantly increased each year from 0.6% in 2011 to 0.8% in 2013 (P < .01; Figure 1). In addition, percentages for linkage to HIV medical care within any time frame and linkage within 90 days significantly increased each year (P < .01; Figure 2).

FIGURE 1—

Number of HIV testing events and percentages of first-time testers and newly identified HIV-positive persons in US sexually transmitted disease clinics: 2011–2013.

Note. First-time testers: P < .01 between all years; newly identified HIV positivity: P < .01 between all years. The numbers of health departments with data for sexually transmitted disease clinics in 2011 to 2013 were 43, 54, and 56, respectively.

FIGURE 2—

Number of HIV-positive persons and percentage linked to HIV medical care in US sexually transmitted disease clinics: 2011–2013.

Note. Linkage to HIV medical care within any time frame P < .01 between all years; linkage to HIV medical care within 90 days: P < .01 between 2012 and 2013. Linkage to HIV medical care within 90 days was a required reporting variable in 2012 and 2013.

DISCUSSION

We found that STD clinics accounted for 18.6% of all CDC-funded HIV testing events and 27.3% of all newly identified HIV-positive persons from CDC-funded tests in 2013. Overall, 0.8% of all persons tested in STD clinics were newly identified as HIV-positive, compared with 0.5% of those at all CDC-funded testing events in 2013. In addition, among CDC-funded tests, STD clinics identified approximately 30.0% of all newly identified HIV-positive African American MSM, Hispanic or Latino MSM, and MSM overall in 2013, suggesting that STD clinics are successful at reaching these populations at higher risk. Half of all CDC-funded testing events in STD clinics were conducted among African Americans, and more than one third of Hispanic or Latino heterosexual male clients tested in STD clinics were first-time HIV testers. Finally, although MSM accounted for 11.5% of testing events in STD clinics, they accounted for 50% of newly identified HIV-positive persons, and African Americans accounted for 55% of newly identified HIV-positive persons. These findings are consistent with previous findings indicating that STD clinics serve populations who are disproportionately at risk for HIV.13,16–20

For finding new cases of HIV, STD clinics appear to be a relatively efficient venue, especially if the comparison is extended beyond the CDC-funded testing noted previously. Estimates for the proportion of persons (aged 18–64 years) in the United States tested in any recent year fall between 10.0% and 22.0% depending on the year and source.24,25 Drawing from Census Bureau projections of 196.5 million US residents aged 18 to 64 years in 2013, this suggests that approximately 20 million to 43 million HIV tests were conducted. HIV surveillance yielded 47 352 diagnoses reported in 2013,7 so STD clinics provided approximately 1 in 10 new case reports (n = 4766) from 1.4% to 3.1% of all tests. Overall HIV incidence in the United States has remained stable and was estimated at approximately 48 000 cases in 2010,3 so new cases from STD clinics in 2013 also account for about 1 in 10 of new diagnoses.

Early initiation of and adherence to antiretroviral therapy has substantial medical benefits to HIV-positive persons and prevention benefits by reducing HIV transmission to HIV-negative partners by up to 96%.10,11 Therefore, in addition to increasing knowledge of HIV status and identification of new positives, it is critical to ensure that all HIV-positive persons receive necessary HIV prevention, care, and treatment services. The National HIV/AIDS Strategy12 has set goals of reducing new HIV infections and linking 85% of newly diagnosed HIV-positive persons to HIV medical care within 90 days by 2015. In 2013, only 55.3% of newly identified HIV-positive persons in STD clinics were linked to medical care within 90 days, and 63.8% were linked within any time frame. Referral to partner services was higher at 73.5%, but interview percentages for partner services and referral to HIV prevention services need improvement at 62.2% and 66.9%, respectively. Linkage rates, in particular, could be significantly improved to ensure that HIV-positive persons have access to care and treatment services. Of note, African Americans were linked to HIV medical care with any time frame and within 90 days, referred to partner services, and interviewed for partner services at a much lower percentage than were Whites and Hispanics or Latinos. Further research is needed to understand the differences in linkage and HIV service delivery among certain racial/ethnic groups.

Limitations

The findings are subject to limitations. Because we focused only on CDC-funded HIV testing events, these findings might not be generalizable to the entire United States. Reliable estimates are not available to determine what proportion of all HIV tests in the United States is CDC-funded. Also, because of missing data, the service delivery data are likely an underestimate and represent the minimum percentage achieved, particularly for linkage to HIV medical care within 90 days. Data for target populations are only required in non–health care settings and for HIV-positive testing events in health care settings. However, some jurisdictions submitted data on HIV-negative persons from health care settings and those data are reflected in the numbers for HIV-testing events and first-time testers.

Linkage to HIV medical care within 90 days and interview for partner services became CDC-required reporting variables starting in 2012. This may contribute to poorer data quality and incomplete data reporting on these 2 service delivery indicators because of the time it may take grantees to update their data systems for reporting. However, there have been significant improvements in data quality each year, specifically for both linkage to HIV medical care variables and referral data. Finally, because we used self-report to identify a new HIV diagnosis, the number of persons newly diagnosed as HIV-positive reported likely represents an overestimation of new positives.

Conclusions

Limitations notwithstanding, among CDC-funded testing events, STD clinics found a meaningful proportion of newly identified HIV-positive persons and are settings to target persons who might otherwise not seek HIV testing or medical evaluation. HIV testing in STD clinics has added value if the testing can be sustained through CDC funding or through other sources, such as reimbursement from insurance. HIV testing in health care settings is a US Preventive Services Task Force A recommendation and, therefore, is likely to be a covered service in many plans.26 The STD clinics vary considerably in the extent to which they can manage third-party billing.27,28 However, the impact of changes to insurance and billing is an avenue for continued exploration in public clinics in general.

The success of linkage to HIV medical care varies within and across jurisdictions and populations,29–31 with implementation research32 the putative route to understand the barriers of linkage efforts so that improvements can be made. The STD clinics may contribute to partnerships between public health entities and HIV-care facilities. Finally, HIV partner services are common in STD clinic settings and a priority service for HIV.23,33 They have value to HIV-positive persons and exposed partners by distributing prevention and care through social and sexual networks and serving to increase public health understanding of the epidemiology of HIV for prevention programs.34 Because STD clinics are a substantial source of newly diagnosed HIV infections and a resource for better understanding the HIV epidemic in the United States, they are important to HIV prevention and control in the United States.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Lisa Belcher, Argelia Figueroa, NaTasha Hollis, and Tanja Walker for their contribution to the data quality assurance process and preparation of the data set.

Human Participant Protection

This data collection is considered a nonresearch program evaluation activity by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; therefore, approval from the institutional review board was not required. The Office of Management and Budget approved this activity.

References

- 1.Bradley H, Hall HI, Wolitski RJ et al. Vital signs: HIV diagnosis, care, and treatment among persons living with HIV—United States, 2011. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(47):1113–1117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV care saves lives: viral suppression is key. 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/HIV-AIDS-medical-care. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;17(4) Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_hssr_vol_17_no_4.pdf. Accessed September 23, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 U.S. dependent areas—2012. 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/surveillance_report_vol_19_no_3.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2014.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among gay and bisexual men. 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/gender/msm/facts. Accessed February 17, 2015.

- 6.Purcell DW, Johnson CH, Lansky A et al. Estimating the population size of men who have sex with men in the United States to obtain HIV and syphilis rates. Open AIDS J. 2012;6:98–107. doi: 10.2174/1874613601206010098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2013. 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/2013/surveillance_Report_vol_25.html. Accessed February 26, 2015.

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hispanic or Latino populations. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/populations/REMP/hispanic.html. Accessed May 26, 2015.

- 9.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG et al. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(18):1815–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White House Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States. 2010. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/NHAS.pdf. Accessed April 24, 2014.

- 13.Weinstock H, Dale M, Linley L, Gwinn M. Unrecognized HIV infection among patients attending sexually transmitted disease clinics. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(2):280–283. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. The intersection of violence, substance use, depression, and STDs: testing of a syndemic pattern among patients attending an urban STD clinic. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(7):614–620. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30639-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalichman SC, Pellowski J, Turner C. Prevalence of sexually transmitted co-infections in people living with HIV/AIDS: systematic review with implications for using HIV treatments for prevention. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(3):183–190. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.047514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helms DJ, Weinstock HS, Mahle KC et al. HIV testing frequency among men who have sex with men attending sexually transmitted disease clinics: implications for HIV prevention and surveillance. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50(3):320–326. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181945f03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campos-Outcalt D, Mickey T, Weisbuch J, Jones R. Integrating routine HIV testing into a public health STD clinic. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(2):175–180. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sheffler-Collins S. Evaluating linkage to care for individuals with newly diagnosed HIV in the Philadelphia Department of Public Health STD clinic. Poster presented at: 2014 National STD Prevention Conference; June 10, 2014; Atlanta, GA.

- 19.Carey MP, Coury-Doniger P, Senn TE, Vanable PA, Urban MA. Improving HIV rapid testing rates among STD clinic patients: a randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. 2008;27(6):833–838. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begley E, VanHandel M. Provision of test results and posttest counseling at STD clinics in 24 Health Departments: US, 2007. Public Health Rep. 2012;127(4):432–439. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley H, Asbel L, Bernstein K et al. HIV testing among patients infected with Neisseria gonorrhoeae: STD surveillance network, United States, 2009–2010. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(3):1205–1210. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended prevention services. 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/programs/pwp/partnerservices.html. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Institutes of Health. Recommendations for HIV prevention with adults and adolescents with HIV in the United States, 2014. Available at: http://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/26062. Accessed December 12, 2014.

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV testing trends in the United States, 2000–2011. 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/testing_trends.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2015.

- 25.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. HIV testing in the United States. 2014. Available at: https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/6094-14-hiv-testing-in-the-united-states1.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2015.

- 26.Moyer VA US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(1):51–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Washburn K, Goodwin C, Pathela P, Blank S. Insurance and billing concerns among patients seeking free and confidential sexually transmitted disease care: New York City sexually transmitted disease clinics 2012. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41(7):463–466. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Downey L, Lafferty WE, Krekeler B. The impact of Medicaid-linked reimbursements on revenues of public sexually transmitted disease clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29(2):100–105. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200202000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yehia BR, Ketner E, Momplaisir F et al. Location of HIV diagnosis impacts linkage to medical care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(3):304–309. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh S, Bradley H, Hu X, Skarbinski J, Hall HI, Lansky A. Men living with diagnosed HIV who have sex with men: progress along the continuum of HIV care—United States, 2010. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(38):829–833. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gant Z, Bradley H, Hu X, Skarbinski J, Hall HI, Lansky A. Hispanics or Latinos living with diagnosed HIV: progress along the continuum of HIV care—United States, 2010. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(40):886–890. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JJ, Maulsby C, Kinsky S et al. The development and implementation of the national evaluation strategy of Access to Care, a multi-site linkage to care initiative in the United States. AIDS Educ Prev. 2014;26(5):429–444. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2014.26.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The recommendations for partner services programs for HIV infection, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydial infection. 2008. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/partners/Partner-Services.html. Accessed December 12, 2014. [PubMed]

- 34.Brewer DD. Case-finding effectiveness of partner notification and cluster investigation for sexually transmitted diseases/HIV. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(2):78–83. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000153574.38764.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]