Abstract

We investigated how industry claim-makers countered concerns about obesity and other nutrition-related diseases in newspaper coverage from 2000, the year before the US Surgeon General’s Call to Action on obesity, through 2012. We found that the food and beverage industry evolved in its response. The defense arguments were made by trade associations, industry-funded nonprofit groups, and individual companies representing the packaged food industry, restaurants, and the nonalcoholic beverage industry. Individual companies used the news primarily to promote voluntary self-regulation, whereas trade associations and industry-supported nonprofit groups directly attacked potential government regulations. There was, however, a shift away from framing obesity as a personal issue toward an overall message that the food and beverage industry wants to be “part of the solution” to the public health crisis.

Since 2001, when the US Surgeon General issued a Call to Action to address obesity,1–3 public health advocates have proposed a range of policies to improve the food and beverage environment. The food industry has strongly opposed many of these initiatives, at times using tobacco industry tactics including corporate social responsibility programs and personal responsibility rhetoric.4–7 Corporate social responsibility can take many forms, including industry adoption of self-policing strategies intended to resolve public health concerns.7–10 The food industry has launched and widely publicized a number of self-regulatory programs,11–14 but research suggests that these initiatives may have done little to mitigate unhealthful food environments.15–28 Past analyses suggest that the food industry also has used personal responsibility rhetoric to shift responsibility for health harms from the industry and its products onto individuals,4 influence how the public addresses obesity, and fight government regulation of its products and marketing practices.4–7

News coverage is an important part of the public conversation about social issues such as obesity. The news helps establish which issues appear on the public agenda, and influences how the public and policymakers view these problems and craft potential solutions.29–33 Social problems such as obesity are defined by how they are framed and who is influencing the framing.34 “Framing” refers to how an issue is portrayed and understood, and involves emphasizing certain aspects of an issue to the exclusion of others.35 News coverage is a key site in which framing takes place. Frames in the news are “persistent patterns” by which the news media organize and present stories.36 Frames help readers construct meaning consciously or unconsciously,37 and shape the parameters of public policy debates by promoting “a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described.”35(p52)

Because of the importance of the news in how readers understand contemporary issues,38 news framing is a site of power struggles in which multiple groups contest to shape public perception of an issue.39,40 Different speakers or “claim-makers” quoted in the news frame the same issue in conflicting ways to serve their interests. Examining their claims offers insights into the range of perspectives represented on a particular issue.41–45

Among the key claim-makers for the food and beverage industry (hereafter “food industry”) are food companies, trade associations, and industry-funded nonprofit organizations. Individual food and beverage companies include companies that sell packaged food (e.g., Kraft), restaurant meals (e.g., McDonald’s), and nonalcoholic beverages (e.g., Coca-Cola). Individual companies may comment about public policy in the news, but they also form trade associations that advocate the interests of groups of food companies.46–49 Trade associations are the public voice of an industry,50 and often lobby or otherwise influence government decision-making.51–53 Trade associations also engage in public relations to exercise political influence, including advocacy advertising and speaking with the press.51

There are numerous food industry trade associations representing the interests of different sectors of the industry such as packaged food manufacturers (e.g., Grocery Manufacturer’s Association), restaurants (e.g., National Restaurant Association), beverage companies (e.g., American Beverage Association [ABA]), and food retailers (e.g., Food Marketing Institute). The food industry also funds nonprofit groups to speak on its behalf. When these groups use names that evoke grassroots consumer advocacy and do not alert the public to their connection with industry they are known as “front groups.”4 The Center for Consumer Freedom (CCF) and Americans Against Food Taxes are 2 primary examples.54

To understand how the food industry has presented itself in the news in the context of obesity policy debates, we investigated how key industry claim-makers countered concerns about obesity and other nutrition-related diseases in newspaper coverage. We collected data from 2000, the year before the 2001 US Surgeon General’s Call to Action and the advent of widespread concern about obesity as a public health problem, through 2012, the last full year of data available at the time. Previous studies have tracked news coverage of obesity and childhood obesity over time,55–57 and assessed the degree to which the food industry is framed as a cause of obesity or as a potential point of intervention. These studies documented increases in obesity coverage throughout the early 2000s, and a growing trend toward addressing societal causes of and solutions to the problem of obesity, including food industry actions. However, these previous analyses have not evaluated the actual statements made by food industry claim-makers in the news.55,56

For this analysis we compared the claims made by food industry trade associations, industry-funded nonprofit groups, and individual companies. We also examined the nuances among statements made by claim-makers representing the interests of the packaged food industry, restaurants, and the nonalcoholic beverage industry.

METHODS

We used the Nexis newspaper database to conduct a keyword search for articles published from 2000 to 2012 in 5 major US newspapers: Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, and Chicago Tribune. These papers, which we previously analyzed for tobacco industry responsibility claims in the news,58–60 are among the 10 highest-circulation newspapers in the country. We selected the New York Times for its status as the national paper of record, the Washington Post for its in-depth coverage of national policy issues, and the Wall Street Journal as the country’s highest-circulating paper and because it focuses on business issues. Finally, we selected the Los Angeles Times and the Chicago Tribune to capture possible regional differences.

We searched for articles that included a reference to obesity, overweight, or nutrition, and at least 1 of the following responsibility-related keywords: responsibility, choice, blame, lifestyle, decision, habits, problem, or freedom. Articles also had to mention at least 1 prominent food industry trade group or industry-funded nonprofit organization. Drawing upon our ongoing media monitoring of food industry marketing policies and practices, we assembled a list of prominent food and beverage industry organizations.61,62 We supplemented this list by conducting Internet searches for food industry trade associations and searches of the Nexis news archive until we reached content saturation (Appendix A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, for our search algorithm).

We removed articles that made only passing references to obesity or diet-related chronic disease. For example, we excluded an article about vegetarianism that mentioned “the medical community’s warnings about obesity” as a possible reason for reducing meat consumption and a study by the National Restaurant Association about vegetarian eating habits.63

Three trained coders examined each article for arguments made by food or beverage industry representatives. We considered arguments to be specific elements that represent and express the underlying frame. We used an iterative process64 to design our coding instrument, which was adapted from our previous work analyzing tobacco industry responsibility claims in the news.58–60 The coding instrument identified 7 discrete food industry arguments about obesity or policies to address obesity (Table 1). We used the sentence as the unit of analysis for arguments: we coded each sentence containing a quote or attribution from a food industry representative; sentences could contain multiple arguments.

TABLE 1—

Obesity-Related Arguments Made by the Food Industry in Major Newspapers: United States, 2000–2012

| Argument Type (% of All Arguments) | Exemplar |

| Industry is part of the solution (33%) | “We are a strong believer and supporter of self-regulation and the current industry proposals to strengthen that.”—Alan Harris, Chief Marketing Officer, Kellogg Co.65(pB1) |

| Government overreach (25%) | “The government doesn’t have the right to social engineer. It doesn’t have a right to protect us from ourselves.”—J. Justin Wilson, Research Analyst, Center for Consumer Freedom66(pB1) |

| Products are not responsible (24%) | “Childhood obesity is the result of many factors. Blaming it on a single factor, including soft drinks, is nutritional nonsense.”—Richard Adamson, Vice President for Scientific and Technical Affairs, National Soft Drink Association67(pT10) |

| Individuals are responsible (15%) | Food establishments “should not be blamed for issues of personal responsibility and freedom of choice.”—Steven Anderson, President, National Restaurant Association68(pCN15) |

| Obesity is not a problem (3%) | “Americans have been force-fed a steady diet of obesity myths by the ‘food police,’ trial lawyers, and even our own government.”—Center for Consumer Freedom advertisement quoted in a news article69(p12) |

Note. Our coding instrument contained 7 discrete arguments. We combined 3 related codes into the overall argument category that “Individuals are responsible” for the purpose of analysis (arguments relating to personal responsibility for obesity, parental responsibility, and those arguing that individuals should know that certain foods lead to obesity or other diet-related diseases).

We recorded arguments attributed to food industry trade groups and nonprofits included in our search string. We also recorded arguments from other trade groups or nonprofits that appeared in the articles, as well as individual food or beverage companies (e.g., Kellogg’s) or the food industry in general (e.g., “Food industry executives say . . .”). Appendix B (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) contains a list of the food companies that made comments about obesity in our sample.

We recorded the speaker for each argument, indicating whether the speaker represented a trade association, an individual company, an industry-funded nonprofit group such as the CCF, or the food industry in general. We also noted whether the speaker represented the packaged food industry, the nonalcoholic beverage industry, the restaurant industry, or food retailers (i.e., grocery, vending, and convenience store representatives).

We established intercoder reliability with Krippendorff’s α by using an iterative method64 of reading a subsample of articles, coding them, and adjusting the coding instrument until we reached an acceptable level of agreement among the coders (α = 0.78 for arguments; α = 0.93 for speakers).70

To assess statistical differences between categories of speakers, we conducted 2-sample proportion tests with Stata software (version 13.0, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Between 2000 and 2012, we found 393 news articles containing obesity-related arguments that referenced a trade association or industry-funded nonprofit organization and included our search terms. These articles contained 1426 responsibility arguments (Appendix C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, for details on the search results). Most of these articles included arguments solely from trade associations or nonprofit groups (68%). About 1 in 5 articles (21%) contained arguments from individual companies and trade associations or nonprofit groups, and 10% contained arguments from individual companies alone. The remainder contained only obesity-related arguments attributed to the food industry in general (e.g., “The food industry claims that . . . .”; 2%).

Food industry arguments appeared most often in news coverage of policy developments and major obesity-related studies and reports. Arguments about obesity from food industry representatives were almost nonexistent in the year before the 2001 Surgeon General’s Call to Action (< 1%; Appendix D, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). The number of arguments made by industry increased sharply thereafter, peaking in 2005 when industry representatives responded to a combination of obesity-prevention policy developments,71–74 and launched self-regulatory initiatives such as limits on soda in schools and McDonald’s placement of nutrition facts on its food packaging.75,76 Starting in 2009, the industry’s presence in newspaper coverage rose again, as representatives responded to a growing number of public health policy actions, including the Affordable Care Act’s menu-labeling provision in 2010 and various state and local efforts to regulate sugar-sweetened beverages.77–79

Arguments From Food Industry Claim-Makers

Food industry claim-makers employed 3 main claims when they appeared in obesity-related newspaper coverage: they praised the industry and its self-regulation programs as “part of the solution”73(pC1) (33% of all food industry arguments), they criticized the government and public policy efforts to prevent obesity (25%), and they claimed that their products were not responsible for poor health outcomes and, therefore, they were unfairly blamed in these debates (24%).

Less frequently, they argued that individual consumer choices were responsible for obesity (15%), or that concern about the obesity epidemic was overstated (3%). Table 1 includes an exemplar of each argument type.

Arguments From Trade Associations, Companies, and Nonprofit Groups

Food industry claim-makers consisted of trade associations, individual companies, industry-funded nonprofit organizations and statements attributed to the “food industry” or “food companies” in general.

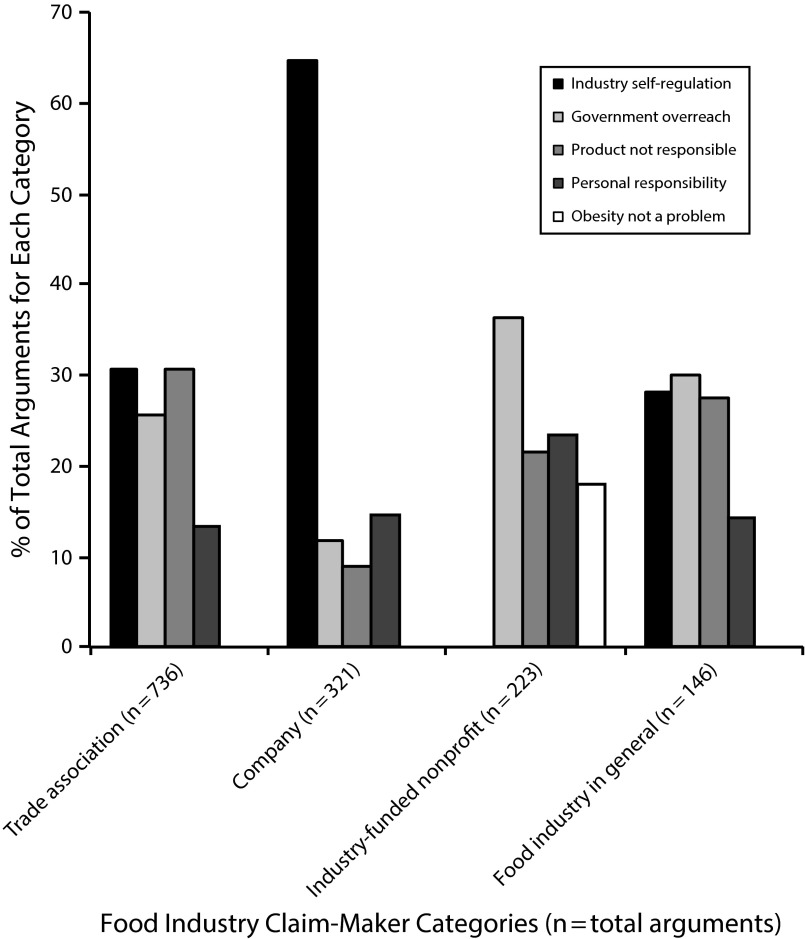

Spokespeople for trade associations used the news in equal measure to dispute their products’ health harms, praise their industry, and criticize the government (Figure 1). To a lesser extent, these representatives also made appeals to individual consumer responsibility. Arguments attributed to the food industry in general followed a very similar pattern.

FIGURE 1—

Arguments about obesity made by food industry claim-makers in major newspapers: United States (n = 1426), 2000–2012.

By contrast, individual company spokespeople focused overwhelmingly on promoting their company or industry as a good corporate actor (64% of their arguments, compared with 31% of the arguments for trade associations; Z = 10.38; P < .001). For example, a McDonald’s spokesman described his company’s approach to obesity as “very responsive and responsible.”80(pF1) Individual companies were also much less likely than other groups to criticize the government or its policies, or to claim that their products were not responsible for health harms. For example, when then–New York Governor David Paterson proposed a soda tax, a Pepsi bottling lobbyist commented that PepsiCo “had specifically instructed its representatives not to raise the threat of job loss, because . . . Pepsi wanted to be a good corporate citizen.”81(pA14) Meanwhile, PepsiCo’s main trade association, the ABA, made this exact claim about the proposal, calling the tax a “money grab” that “could jeopardize jobs.”82(pA36)

In our sample, arguments by food industry–funded nonprofit groups such as antisoda tax coalitions or the CCF (which accounted for 88% of the arguments from nonprofit groups in our sample) never praised industry efforts and were much more likely to criticize government and evoke personal responsibility. These groups focused on framing any regulation of the food industry as a “slippery slope”83 of government intrusion with ominous consequences. Their arguments also were more extreme in tone. In an article about CCF, food executives acknowledged that, “by keeping the sponsors anonymous, [CCF] can be more vociferous, provocative and irreverent in its criticisms than a trade association.”84(pE1)

From 2002 to 2006, the CCF occasionally claimed that the obesity epidemic was exaggerated and not a significant public health problem. When responding to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report on the impact of obesity, CCF analyst Dan Mindus claimed,

A full investigation into the obesity death tally will reveal multiple flaws that seriously overstate the obesity problem and is leading to knee-jerk policymaking and litigation.85(pC1)

This argument rarely appeared after 2006.

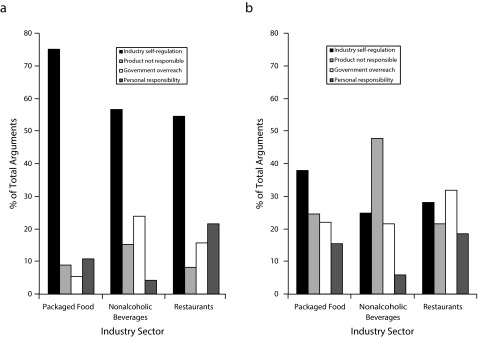

Arguments by Industry Sector

We compared the arguments made by claim-makers representing different food industry sectors. Specifically, we examined arguments from claim-makers representing the packaged food industry (which accounted for 30% of all arguments), the nonalcoholic beverage industry (24%), the restaurant industry (23%), and food retailers (4%). These sectors face distinct types of obesity-related public health interventions. In all sectors, individual companies were significantly more likely than trade associations to praise their own self-regulatory actions (data not shown). Between sectors, trade association arguments varied in correspondence with the different policy challenges each faced (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2—

Arguments about obesity by industry sector in major newspapers as made by (a) companies and (b) trade associations: United States, 2000–2012.

Note. Not included here are retailers (4% of arguments) or arguments not attributed to a specific segment or attributed to multiple segments (3%). The sample size was n = 963.

Packaged food industry.

Claim-makers for the packaged food industry focused more heavily on arguments about industry self-regulation than any other sector. Packaged food companies and associated trade associations primarily praised the packaged food industry as “extremely responsive” and “ahead of the curve” with respect to health concerns,86(p52) often touting product-reformulation or package labeling. These arguments became more prominent starting in 2003, and spiked in years when the packaged food industry was responding to high-profile actions proposed by the government or by public health advocates (Appendix E, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). For example, in 2010, when the US Food and Drug Administration announced that it would draft guidelines for front-of-package labeling, the industry pushed its “Facts Up Front” labeling scheme in the news.87(pA2) It responded to criticisms from public health advocates87 by praising Facts Up Front as an “ambitious revision of food and beverage labels.”88(pB1)

Nonalcoholic beverage industry.

More than any other industry sector, the nonalcoholic beverage industry disputed the health harms of its products, arguing that soda was not responsible for the “complex problem”89(p1) of obesity, or at least not solely responsible. The ABA was the key claim-maker for this argument. The ABA frequently argued that “[i]t makes no sense to single out one particular food product as a contributor to obesity when science shows that's not supportable.”90(pD2) This argument made up almost half of the ABA’s arguments, and until 2004 it was virtually the only argument from soda industry claim-makers that appeared in the news (Appendix F, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Arguments about self-regulation from beverage companies and the ABA initially appeared in the news infrequently (Appendix F). They increased in the mid-2000s when the industry issued voluntary guidelines restricting beverage sales in schools.12,75 By 2009, the beverage industry again appeared frequently in the news as numerous policy proposals to regulate sugar-sweetened beverages emerged at the local, state, and federal levels. Both individual companies and the ABA critiqued these proposals as government overreach and “discriminatory”91(pB3) against soda, and touted the beverage industry’s redoubled self-regulatory initiatives.92–95 For example, a Coca-Cola spokesperson argued that voluntary initiatives including its “Calories Count” program “can have a meaningful impact on the obesity issue.”91(pB3)

Restaurant industry.

Restaurant industry claim-makers’ arguments changed considerably between 2001 and 2012 (Appendix F). In the early 2000s, the restaurant industry was grappling with the threat of obesity-related lawsuits against fast-food restaurants.96 In response, individual companies and trade associations commonly argued in the news that food choices and related health issues were a matter of personal responsibility with statements such as “People make the choice to eat what they want and when they want, every day.”97(pCN1)

In 2004 and 2005, the industry launched a number of voluntary self-regulatory efforts. For example, McDonald’s announced it would end supersizing and put nutrition information on packaging.98,99 During this time, both companies and restaurant trade associations appeared primarily in the news to praise this and other voluntary initiatives.

From 2006 to 2009, the restaurant industry faced proposals to regulate trans fats and nutrition information on menus. The industry’s main response in the news, mostly voiced by trade associations, was to criticize these government actions. A California Restaurant Association spokesperson asked, for example, “With crime and budget shortfall issues, why are city and state legislators focusing on trans fats and fast food restaurants?”100(pC1)

In 2010, the National Restaurant Association, the main US restaurant trade association, announced its support for a national menu-labeling requirement. At that point, claim-makers for the restaurant industry returned to self-promoting statements touting the industry as a good corporate citizen by virtue of its support for the pending regulation and for other programs.101(pB1) For example, in 2011, the National Restaurant Association launched the Kids LiveWell program for healthier children’s meals and frequently touted this program in the news, arguing that “restaurants can be a part of the solution to ensuring a healthier generation.”102(pB2)

DISCUSSION

As obesity emerged in the early 2000s as a significant public health concern and a public policy target, the food industry took to the news as part of its efforts to head off potential public health interventions. Our findings roughly mirrored the pattern in news coverage of obesity described in earlier studies,55,56 increasing rapidly through the mid-2000s, then decreasing for a few years, and surging again toward the end of the decade.

Earlier analyses have suggested that personal responsibility rhetoric might play an important role in food industry efforts to forestall public health interventions.4,6,7 We found that although food industry representatives did employ personal responsibility arguments in the news, arguing that consumers were responsible for their own health was not a dominant theme during the period we analyzed.

Food and Beverage Companies Congratulate Themselves

We found clear distinctions between food industry claim-makers. Individual companies used the news primarily to promote voluntary self-regulation. Their emphasis on voluntary efforts implied that government regulation was unnecessary and allowed companies to position themselves in the news as good corporate citizens and part of the solution to the health crisis.

Company spokespeople largely avoided discussing government regulation or acknowledging accusations that their products contributed to obesity. This was likely part of a strategic effort to protect valuable brand reputations.

Trade Associations and Nonprofits Go on the Attack

Trade associations and industry-supported nonprofit groups, on the other hand, directly attacked potential government regulations. These groups, which are not connected to specific companies or brands in the media, were much more likely to make negative arguments explicitly critiquing policies or disputing products’ health harms. Food industry–funded nonprofit organizations made particularly extreme critiques of proposed regulations, and derided public health concerns about obesity. Despite their partial funding by the food industry, these nonprofits were portrayed in the news as independent organizations. This may have afforded them more latitude to make incendiary statements without the risk of tarnishing the public image of individual companies.

Our findings also suggest that trade associations and industry-funded nonprofits may have shielded their member companies to some extent from having to comment on major obesity-related public policy proposals in the news. When trade associations or industry nonprofits appeared in the news about obesity, they often appeared in place of individual companies: more than two thirds of articles in our sample contained commentary only from a trade association or industry-funded nonprofit, and food companies were absent. This finding suggests that these groups have a high level of legitimacy with the press, and are seen as credible spokespeople who can speak on behalf of food companies. It is also possible that individual companies refused to comment on the record about controversial policy issues, leaving journalists few other sources.

Shifts Over Time in How Claim-Makers Discuss Obesity

We also saw changes over time in how food industry claim-makers talked about obesity. The CCF, for example, made controversial claims in the early 2000s that the obesity epidemic and associated health harms were overstated. After 2006, the group largely stopped using this argument. The argument may have no longer benefited the industry as it introduced self-regulatory initiatives to combat obesity, and used the news to position itself as “part of the solution.”79,102

We also observed dramatic shifts over time in arguments from the restaurant sector. In the early 2000s, restaurant spokespeople primarily framed obesity as an issue of personal responsibility—one that restaurants had no part in. However, as time went on, they increasingly switched to arguments praising the industry for its response to obesity concerns, both for its new self-regulatory programs, and its support of the 2010 national menu-labeling legislation (which preempted local and state legislation that might have gone further to protect consumers).103

These types of shifts may be an indication that public pressure about obesity was having an effect: obesity was no longer something that could be minimized or put aside as a personal issue. Instead, industry spokespeople increasingly talked about the issue as a serious problem that needed to be addressed. However, they remained at odds with lawmakers and public health advocates about how it should be addressed, and what was to blame for the problem.

Implications for Public Health

Public health advocates working to create a healthier food environment should keep in mind that the food industry is not monolithic. As news coverage of obesity and diet-related chronic disease continues, individual companies will likely continue to focus on positive messages about their products and actions, leaving trade associations or other industry-wide groups to contest public health interventions or claims that their products cause health harms. It will be important for the public health community to be prepared to address both of these tactics. In particular, it may be helpful to highlight the harmful practices of specific companies, so they cannot shield their reputations behind neutral industry associations.

Highlighting companies’ harmful practices will aid in “denormalizing” or stigmatizing these companies’ activities and products not as business as usual, but as sharing responsibility for the current health crisis. Denormalization tactics have been extremely effective in shifting blame from individual smokers or the act of smoking to the tobacco industry and its harmful practices.104,105 Denormalizing the food industry requires repositioning unhealthy products as harmful, portraying corporations’ activities as disease vectors,105 and highlighting the disingenuous use of industry’s corporate social responsibility programs as brand marketing efforts.5,7,104,106

Public health advocates should draw particular attention to the food industry’s efforts to use the news to publicize its self-regulatory corporate social responsibility programs as “part of the solution” to the obesity crisis. Starting in the early 2000s, the food industry has positioned its self-regulatory programs, especially those associated with its brands, as meaningful responses to the obesity crisis. Food industry claim-makers have been successful in their efforts to highly publicize self-regulatory programs in the news, even though these programs have been routinely shown to do little to improve food and beverage environments.15–26,107 Advocates and researchers should encourage journalists to investigate food industry representatives’ claims about self-regulatory programs, including whether the programs have been independently evaluated.107

Our work also has implications for advocates and researchers concerned with the actions of other industries affecting the food supply and public health. For example, manufacturers of genetically modified organisms and the alcoholic beverage industry are both involved in high-stakes debates to protect their reputations and avoid government intervention.6,108 Comparing the strategic use of responsibility arguments to combat public health interventions across industries could be a rich area for further research that may inform subsequent policy and advocacy efforts to protect the public’s health.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Although news coverage of obesity-related topics provides a valuable window into the food industry’s efforts to frame public debate around obesity, it only captures a small segment of the industry’s larger public relations efforts to shape perceptions, including television and online media,5,109 which were not captured by this analysis. In addition, we searched for articles that mentioned industry trade associations and industry-funded nonprofit groups, which limited our analysis of statements by individual companies. Future research could explore all food industry statements in the news and other mass media.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest a number of opportunities for future research on the food industry’s responses to the dynamic landscape of public health policies. Our research focused on news coverage in the United States, but many of the companies we studied are multinational, and future research could examine how the food industry has responded to obesity concerns internationally. In addition, media relations is only 1 aspect of the food industry’s efforts to influence public policy, and research comparing the industry’s statements in the media with its regulatory and lobbying activities, including public comments, could be highly valuable. Researchers should also track the food industry’s responses as new policy strategies emerge, and existing interventions are implemented. Soda taxes, for example, have triggered strong opposition campaigns from the beverage industry, and analyzing the industry’s messages and tactics around this emerging public health intervention, both in newspapers and other media, could be important for the field.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge grant support from the National Cancer Institute (2R01CA087571).

We thank Rebecca Womack, MPH, for her research assistance.

Human Participant Protection

This research did not involve human participants and, thus, is not subject to institutional review board approval.

References

- 1.Stroup DF, Johnson V, Proctor DC, Hahn RA. Reversing the trend of childhood obesity. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(3):A83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karpyn A, Young C, Weiss S. Reestablishing healthy food retail: changing the landscape of food deserts. Child Obes. 2012;8(1):28–30. doi: 10.1089/chi.2011.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Consumers Union. Out of balance: marketing of soda, candy, snacks and fast foods drowns out healthful messages. 2005. Available at: http://consumersunion.org/wp-content/uploads/2005/09/OutofBalance.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2014.

- 4.Brownell KD, Warner K. The perils of ignoring history: Big Tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is Big Food? Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):259–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorfman L, Cheyne A, Friedman L, Wadud A, Gottlieb M. Soda and tobacco industry corporate social responsibility campaigns: how do they compare? PLoS Med. 2012;9(6):e1001241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moodie R, Stuckler D, Monteiro C et al. Profits and pandemics: prevention of harmful effects of tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed food and drink industries. Lancet. 2013;381(9867):670–679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiist WH. The corporate play book, health, and democracy: the snack food and beverage industry’s tactics in context. In: Stuckler D, Siegel K, editors. Sick Societies: Responding to the Global Challenge of Chronic Disease. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2011. p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vladeck D. Prepared statement of the Federal Trade Commission on the Interagency Working Group in Food Marketed to Children before the House Energy and Commerce Committee Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade and the Subcommittee on Health. Available at: http://www.ftc.gov/os/testimony/111012foodmarketing.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2014.

- 9.Watzman N. Food and media companies lobby to weaken guidelines on marketing food to children. Available at: http://reporting.sunlightfoundation.com/2011/Food_and_media_companies_lobby. Accessed February 3, 2014.

- 10.ElBoghadady D. Lawmakers want cost–benefit analysis on child food marketing restrictions. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/lawmakers-want-cost-benefit-analysis-on-child-food-marketing-restrictions/2011/12/15/gIQAdqxywO_story.html. Accessed February 3, 2014.

- 11.Kolish E, Hernandez MD, Blanchard K. The Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative in action: compliance and implementation during 2010 and five year retrospective 2006–2011. 2011. Available at: http://www.bbb.org/storage/16/documents/cfbai/cfbai-2010-progress-report.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2014.

- 12. The American Beverage Association. Alliance school beverages progress report. 2010. Available at: http://www.ameribev.org/files/240_School Beverage Guidelines Final Progress Report.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2014.

- 13.National Restaurant Association. Kids LiveWell. Healthful choices. Happy kids. Available at: http://www.restaurant.org/foodhealthyliving/kidslivewell. Accessed February 3, 2014.

- 14.McDonald’s USA. McDonald’s USA’s new Happy Meal Campaign. Available at: http://news.mcdonalds.com/Files/04/0427ecc6-c6ba-4959-906a-7e10b743a958.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2015.

- 15.Harris JL, Fox T. Food and beverage marketing in schools: putting student health at the head of the class. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(3):206–208. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.5003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris JL, Sarda V, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Redefining “child-directed advertising” to reduce unhealthy television food advertising. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(4):358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris JL, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD . New Haven, CT: Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity; Sugary drink FACTS: evaluating sugary drink nutrition and marketing to youth. 2011. Available at: http://www.sugarydrinkfacts.org/resources/SugaryDrinkFACTS_Report.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris JL, Speers SE, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. US food company branded advergames on the Internet: children’s exposure and effects on snack consumption. J Child Media. 2012;6(1):51–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell LM, Harris JL, Fox T. Food marketing expenditures aimed at youth: putting the numbers in context. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(4):453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell LM, Schermbeck RM, Chaloupka FJ. Nutritional content of food and beverage products in television advertisements seen on children’s programming. Child Obes. 2013;9(6):524–531. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell LM, Schermbeck RM, Szczypka G, Chaloupka FJ. Children’s exposure to food and beverage advertising on television: tracking calories and nutritional content by company membership in self-regulation. In: Williams JD, Pasch KE, Collins CA, editors. Advances in Communication Research to Reduce Childhood Obesity. New York, NY: Springer; 2013. pp. 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernhardt AM, Wilking C, Adachi-Mejia AM, Bergamini E, Marijnissen J, Sargent JD. How television fast food marketing aimed at children compares with adult advertisements. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheyne A, Gonzalez P, Mejia P, Dorfman L. Food and beverage marketing to children and adolescents: limited progress by 2012. Minneapolis, MN: Healthy Eating Research; 2013. Available at: http://www.healthyeatingresearch.org. Accessed August 28, 2014.

- 24.Cheyne AD, Dorfman L, Bukofzer E, Harris JL. Marketing sugary cereals to children in the digital age: a content analysis of 17 child-targeted websites. J Health Commun. 2013;18(5):563–582. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.743622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castonguay J, Kunkel D, Wright P, Duff C. Healthy characters? An investigation of marketing practices in children’s food advertising. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45(6):571–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kunkel D, Mastro D, Ortiz M, McKinley C. Food marketing to children on US Spanish-language television. J Health Commun. 2013;18(9):1084–1096. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.768732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris JL, Schwartz MB, Munsell C . Fast Food FACTS 2013: Measuring Progress in Nutrition and Marketing to Children and Teens. New Haven, CT: Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity; 2013. Available at: http://www.fastfoodmarketing.org/media/FastFoodFACTS_Report.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris JL, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD . New Haven, CT: Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity; Cereal FACTS 2012: limited progress in the nutrition quality and marketing of children’s cereals. 2012. Available at: http://www.cerealfacts.org/media/Cereal_FACTS_Report_2012_7.12.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dearing JW, Rogers EM. Agenda-Setting. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCombs M, Shaw D. The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin Q. 1972;36(2):176–187. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gamson W. Talking Politics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCombs M, Reynolds A. How the news shapes our civic agenda. In: Bryant J, Oliver MB, editors. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis; 2009. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheufele D, Tewksbury D. Framing, agenda setting, and priming: the evolution of three media effects models. J Commun. 2007;57(1):9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hilgartner S, Bosk C. The rise and fall of social problems: a public arenas model. Am J Sociol. 1988;94:53–78. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Entman R. Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun. 1993;43(4):51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gitlin T. The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmaking of the New Left. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iyengar S. Is Anyone to Blame? How Television Frames Political Issues. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheufele DA. Framing as a theory of media effects. J Commun. 1999;49(1):103–122. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benford RD, Snow DA. Framing processes and social movements: an overview and assessment. Annu Rev Sociol. 2000;26:611–639. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nisbet MC, Huge M. Where do science debates come from? Understanding attention cycles and framing. In: Brossard D, Shanahan J, Nesbitt TC, editors. The Media, the Public and Agricultural Biotechnology. Wallingford, UK: CAB International; 2007. pp. 193–230. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woodruff K, Dorfman L, Berends V, Agron P. Coverage of childhood nutrition policies in California newspapers. J Public Health Policy. 2003;24(2):150–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kwan S. Framing the fat body: contested meanings between government, activists, and industry. Sociol Inq. 2009;79(1):25–50. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lima JC, Siegel M. The tobacco settlement: an analysis of newspaper coverage of a national policy debate, 1997–1998. Tob Control. 1999;8(3):247–253. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.3.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Menashe CL, Siegel M. The power of a frame: analysis of newspaper coverage of tobacco issues—United States, 1985–1996. J Health Commun. 1998;3(4):307–325. doi: 10.1080/108107398127139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chapman S, Freeman B. Markers of the denormalisation of smoking and the tobacco industry. Tob Control. 2008;17(1):25–31. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.021386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Warner KE. The effects of the anti-smoking campaign on cigarette consumption. Am J Public Health. 1977;67(7):645–650. doi: 10.2105/ajph.67.7.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hilton S, Wood K, Patterson C, Katikireddi SV. Implications for alcohol minimum unit pricing advocacy: what can we learn for public health from UK newsprint coverage of key claim-makers in the policy debate? Soc Sci Med. 2014;102:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henderson J, Coveney J, Ward P, Taylor A. Governing childhood obesity: framing regulation of fast food advertising in the Australian print media. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(9):1402–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parker R. Trade association takes “positives” to consumers (a case history) Public Relations Q. 1980;25(3):17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gupta SK, Brubaker DR. The concept of corporate social responsibility applied to trade associations. Socioecon Plann Sci. 1990;24(4):261–271. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spillman L. Solidarity in Strategy: Making Business Meaningful in American Trade Associations. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nank R, Alexander J. Farewell to Tocqueville’s dream: a case study of trade associations and advocacy. Public Adm Q. 2012;36(4):429–461. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schaefer A, Kerrigan F. Trade associations and corporate social responsibility: evidence from the UK water and film industries. Bus Ethics. 2008;17(2):171–195. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yanamadala S, Bragg MA, Roberto CA, Brownell KD. Food industry front groups and conflicts of interest: the case of Americans Against Food Taxes. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(8):1331–1332. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012003187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barry CL, Jarlenski M, Grob R, Schlesinger M, Gollust SE. News media framing of childhood obesity in the United States from 2000 to 2009. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):132–145. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim SH, Willis LA. Talking about obesity: news framing of who is responsible for causing and fixing the problem. J Health Commun. 2007;12(4):359–376. doi: 10.1080/10810730701326051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lawrence RG. Framing obesity: the evolution of news discourse on a public health issue. Harv Int J Press Polit. 2004;9(3):56–75. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mejia P, Dorfman L, Cheyne A et al. The origins of personal responsibility rhetoric in news coverage of the tobacco industry. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):1048–1051. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheyne A, Dorfman L, Daynard RA, Mejia P, Gottlieb M. The debate on regulating menthol cigarettes: closing a dangerous loophole vs removing the right to have a choice. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):e54–e61. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dorfman L, Cheyne A, Gottlieb MA et al. Cigarettes become a dangerous product: tobacco in the rearview mirror, 1952–1965. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):37–46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berkeley Media Studies Group. Eye on marketers. Available at: http://www.bmsg.org/resources/eye-on-marketers. Accessed August 1, 2014.

- 62.Center for Digital Democracy, Berkeley Media Studies Group. Digitalads.org. Available at: http://www.digitalads.org. Accessed August 1, 2014.

- 63. Bloyd-Peshkin S. The meatless wonders; we’ve been dining on animals since Fred Flintstone first fired up his grill. But with meat alternatives popping up everywhere, the American diet is in flux. Hey, Fred. What you got under that grill top? Are those portobellos? Chicago Tribune. October 5, 2003:C13.

- 64.Altheide DL. Reflections: ethnographic content analysis. Qual Sociol. 1987;10(1):65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ellison S. Food makers propose tougher guidelines for children’s ads. Wall Street Journal. July 13, 2005:B1.

- 66. Lazarus D. Help cure obesity, one penny at a time. Los Angeles Times. February 25, 2011:B1.

- 67. Squires S. Soft drinks, hard facts; The soda industry pays schools millions in its efforts to sell to students. Washington Post. February 27, 2001:T10.

- 68. Jackson D. America’s obesity enablers winning. Chicago Tribune. August 22, 2005:CN15.

- 69. Olsen P, Rodriquez V. Obesity confusion: how fat is too fat? Chicago Tribune. May 2, 2005:12.

- 70.Krippendorff K. Testing the reliability of content analysis data: what is involved and why? In: Krippendorff K, Bock MA, editors. The Content Analysis Reader. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2008. pp. 350–357. [Google Scholar]

- 71.McGinnis JM, Gootman JA, Kraak VI. Washington DC: Institute of Medicine: Committee on Food Marketing and the Diets of Children and Youth; 2005. Food marketing to children and youth: threat or opportunity? [Google Scholar]

- 72. Burros M. Federal advisory group calls for change in food marketing to children. New York Times. December 7, 2005:C1.

- 73. Schmeltzer J. Soda pop is group’s latest label target. Chicago Tribune. July 16, 2005:C1.

- 74. Landsberg M, Morin M. School soda, junk food bans approved. Los Angeles Times. September 7, 2005:B1.

- 75. Pressler MW. Limits set on school drinks sales; companies to stop or reduce vending of sugary drinks. Washington Post. August 18, 2005:D3.

- 76. Pressler MW. McDonald’s plans to print nutrition data on food boxes. Washington Post. October 26, 2005:D1.

- 77.Mejia P, Nixon L, Cheyne A, Dorfman L, Quintero F. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Media Studies Group; Issue 21: Two communities, two debates: news coverage of soda tax proposals in Richmond and El Monte. 2014. Available at: http://www.bmsg.org/sites/default/files/bmsg_issue21_sodataxnews.pdf. Accessed August 28, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bernstein S. On the menu: food values; calorie counts will be required at restaurants nationwide under the healthcare overhaul. Los Angeles Times. March 23, 2010:AA2.

- 79. Peters J. Soda taxes fizzle in wake of industry lobbying. Washington Post. July 14, 2010:A1.

- 80. Burros M. Hold the fries. Hey, not all of them! New York Times. March 10, 2004:F1.

- 81. Hartocollis A. Failure of state soda tax plan reflects power of an antitax message. New York Times. July 3, 2010:A14.

- 82. Chan S. A tax on many soft drinks sets off a spirited debate. New York Times. December 17, 2008:A36.

- 83. Hamburger T, Geiger K. Soda tax fizzles as drink industry stirs up support. Chicago Tribune. February 8, 2010:C19.

- 84. Mayer C, Joyce A. The escalating obesity wars; nonprofit’s tactics, funding sources spark controversy. Washington Post. April 27, 2005:E1.

- 85. Study inflated obesity deaths. Chicago Tribune. November 24, 2004:C1.

- 86. Zero trans fat doesn’t always mean zero. Chicago Tribune. August 24, 2007:52.

- 87. Layton L. Firms bring nutrition labels to fore. Washington Post. January 25, 2011:A2.

- 88. Neuman W. Food makers devise own label plan. New York Times. January 25, 2011:B1.

- 89. DiMassa C, Hayasaki E. L.A. schools set to can soda sales. Los Angeles Times. August 25, 2002:1.

- 90. McKay B. New report argues for tax on soft drinks. Wall Street Journal. September 17, 2009:D2.

- 91. Strom S. Pepsi and Coke to post calories of drinks sold in vending machines. New York Times. October 9, 2012:B3.

- 92. Hsu T. Soda giants’ machines to post calorie counts; critics say initiative by Coca-Cola and others aims to avoid special taxes and rules. Los Angeles Times. October 9, 2012:B1.

- 93. Geiger K, Hamburger T. States poised to become new battleground in soda tax wars; lawmakers in California and elsewhere seek levies on sweetened drinks. Los Angeles Times. February 21, 2010:A22.

- 94. Neely S. Beverages in schools. New York Times. May 5, 2009.

- 95. Wilson D, Roberts J. Lobbyists’ influence thins out efforts to battle child obesity; food and beverage industry more than doubled spending in Washington in past 3 years. Chicago Tribune. May 2, 2012:C3.

- 96.Mello MM, Rimm EB, Studdert DM. The McLawsuit: the fast-food industry and legal accountability for obesity. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22(6):207–216. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.6.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Greenburg JC. Tobacco wins set table for fast-food suits. Chicago Tribune. August 26, 2002:CN1.

- 98.McDonald’s. Nutrition information. Available at: http://www.aboutmcdonalds.com/mcd/sustainability/library/policies_programs/nutrition_and_well_being/nutrition_information.html. Accessed April 14, 2014.

- 99. Carpenter D. McDonald’s to dump supersize portions. Washington Post. March 3, 2004.

- 100. Hirsch J. Stepping up to the plate for more food regulation; state and local officials, worried about health risks, push trans fat bans and menu labels. Some restaurants and manufacturers object. Los Angeles Times. December 17, 2008:C1.

- 101. Rosenbloom S. Most chains told to post calorie data. New York Times. March 24, 2010:B1.

- 102. Bernstein S. More-healthful options for kids are in the works. Los Angeles Times. July 13, 2011:B2.

- 103.Pertschuk M, Pomeranz JL, Aoki JR, Larkin MA, Paloma M. Assessing the impact of federal and state preemption in public health: a framework for decision makers. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2013;19(3):213–219. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182582a57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mahood G. Tobacco industry denormalization: telling the truth about the tobacco industry’s role in the tobacco epidemic. Montreal, QC: Non-Smokers’ Rights Association: Smoking and Health Action Foundation; 2004. Available at: http://www.nsra-adnf.ca/cms/file/files/pdf/TID_Booklet.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2013.

- 105.Leatherdale ST, Sparks R, Kirsh VA. Beliefs about tobacco industry (mal) practices and youth smoking behaviour: insight for future tobacco control campaigns (Canada) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17(5):705–711. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Masheb R. Keep food marketing out of schools, at any price. Al Jazeera America. April 1, 2014. Available at: http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2014/4/general-mills-foodmarketingschoolseducation.html. Accessed April 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kraak VI, Story M, Wartella EA, Ginter J. Industry progress to market a healthful diet to American children and adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(3):322–333. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chokshi N. Big corporate spending pays off in Washington’s genetically modified food fight. Washington Post. June 6, 2013. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/govbeat/wp/2013/11/06/big-corporate-spending-pays-off-in-washingtons-genetically-modified-food-fight. Accessed April 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Warner M. The soda tax wars are back: brace yourself. CBS News. March 25, 2010. Available at: http://www.cbsnews.com/news/the-soda-tax-wars-are-back-brace-yourself. Accessed August 1, 2014. [Google Scholar]