Abstract

Objective

Small-fiber neuropathy causes severe burning pain, requires diagnostic approaches such as skin biopsy, and encompasses two subtypes based on distribution of neuropathic pain. Such biopsy-proven subtypes of small-fiber neuropathies have not been previously described as complications of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-inhibitor therapy.

Methods

We therefore characterized clinical and skin biopsy findings in three rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients who developed small-fiber neuropathies associated with TNF-inhibitors. We also conducted a systematic review of the literature to characterize subtypes of neuropathies previously reported in association with TNF-inhibitor therapy.

Results

Two patients presented with a “non-length-dependent” small-fiber neuropathy, experiencing unorthodox patterns of burning pain affecting the face, torso, and proximal extremities. Abnormal skin biopsy findings were limited to the proximal thigh, which is a marker of proximal-most dorsal root ganglia degeneration. In contrast, one patient presented with a “length-dependent” small-fiber neuropathy, experiencing burning pain only in the feet. Abnormal skin biopsy findings were limited to the distal feet, which is a marker of distal-most axonal degeneration. One patient developed a small-fiber neuropathy in the context of TNF-inhibitor-induced lupus. In all patients, neuropathies occurred during TNF-inhibitor-induced remission of RA disease activity and improved on withdrawal of TNF-inhibitors.

Conclusions

We describe a spectrum of small-fiber neuropathies not previously reported in association with TNF-inhibitor therapy, with clinical and skin biopsy findings suggestive of dorsal root ganglia as well as axonal degeneration. The development of small-fiber neuropathies during inactive joint disease and improvement of neuropathic pain upon withdrawal of TNF-inhibitor suggest a causative role of TNF-inhibitors.

Introduction

The spectrum of known neurological complications that have been described in association with tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-inhibitors has not appreciably changed over the past decade. It is well-established that treatment with TNF-inhibitors is associated with demyelinating syndromes, which can affect both the central and peripheral nervous system (PNS) [1–4]. Because TNF-inhibitors are used across a wide variety of disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and other inflammatory syndromes, it is important for rheumatologists, dermatologists, gastroenterologists, and other medical practitioners to be aware of the spectrum of potential neurological complications associated with these agents.

Small-fiber neuropathy (SFN) is a painful sensory neuropathy that commonly causes burning pain and targets “smaller-caliber” A-delta or unmyelinated C-fiber nerves [5–7]. Because the integrity of unmyelinated nerves cannot be assessed by routine electrodiagnostic studies, alternative diagnostic studies such as skin biopsy are required. However, because of unfamiliarity with this particular type of neuropathy and due to the limitations of electrodiagnostic testing, small-fiber neuropathy patients with normal nerve-conduction studies may be improperly considered as not having objective evidence of PNS disease [6].

Furthermore, it may be under-appreciated that small-fiber neuropathies encompass two distinct entities, which likely reflect mechanisms targeting different anatomic regions in the PNS [7]. In the first entity, which has been termed as a “length-dependent” small-fiber neuropathy, patients report neuropathic pain occurring in a distal “stocking-and-glove” distribution. This traditional pattern of distal neuropathic pain is associated with surrogate skin biopsy markers of distal-most axonal degeneration. Such markers include decreased intra-epidermal nerve-fiber density of unmyelinated nerves, which is reduced at the distal leg compared to the proximal thigh.

In contrast, in the second entity that has been termed as a “non-length-dependent” small-fiber neuropathy, patients experience unorthodox and atypical patterns of neuropathic pain that can affect the face, torso, and proximal extremities [7–13]. Because such neuropathic pain does not conform to traditional peripheral nerve boundaries, patients may be misdiagnosed as having a non-organic pain syndrome. However, skin biopsy findings indicate that this non-traditional pattern of proximal neuropathic pain is associated with skin biopsy markers indicative of neuronal degeneration affecting the proximal-most element in the PNS—the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) [7–13]. In this case, the intra-epidermal nerve fiber density at the distal leg is no longer reduced compared to the proximal thigh.

Yet, this spectrum of small-fiber neuropathies has not previously been described in the context of TNF-inhibitor therapy. In this study, we describe RA patients who developed small-fiber neuropathies while being treated with TNF-inhibitors. We have identified that patients with TNF-inhibitors can develop both non-length-dependent as well as length-dependent small-fiber neuropathies. This report therefore reinforces how all medical specialists who prescribe TNF-inhibitors should be aware of how to recognize and diagnose a small-fiber neuropathy.

Patients and methods

This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. All patients provided informed consent permitting collection of data and analysis of skin biopsy studies.

Study definitions

Small-fiber neuropathies

As previously described, patients were required to have characteristic symptoms reported in small-fiber neuropathies (i.e., burning pain) and neurological examination findings that revealed selective deficits to small-fiber modalities (i.e., pinprick and/or temperature) [5–7]. Additionally, patients were required to lack clinical or electrodiagnostic features of a “larger-fiber” axonal or demyelinating neuropathy.

We defined biopsy-proven small-fiber neuropathies based on the technique of skin biopsy, which permits visualization of unmyelinated C-fibers by immunostaining against the panaxonal protein PGP 9.5 [14–16]. The intra-epidermal nerve fiber density of unmyelinated axons was assessed [14,15], and considered diagnostic of small-fiber neuropathies when decreased compared to standardized normative controls.

Distinction between the entities of a length-dependent versus non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy

As previously described [7–13], we defined length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy in patients with small-fiber symptoms and examination findings restricted to the distal extremities, and having corresponding skin biopsy findings similarly restricted to the distal extremities. Specifically, the intra-epidermal nerve-fiber density of unmyelinated nerves needed to be reduced at the distal extremities compared to the proximal thigh. In contrast, we defined non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy in patients with neuropathic pain and small-fiber findings occurring in proximal regions (i.e., face, torso, arms, and/or proximal extremities). Biopsy-proven non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy was defined by abnormal skin biopsy findings, which are comparable or more severe in the proximal thigh compared to the distal leg.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were required to have no other causes of a small-fiber neuropathy as assessed by a normal 2-h glucose tolerance test (assessing for glucose intolerance and diabetes), vitamin B12, screening for infections (including hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV), antigliadin/antiendomysial IgA/IgG antibodies for celiac disease, serum and protein electrophoresis to evaluate for para-proteinemia/amyloidosis, screening for thyroid dysfunction, and assessment for alcohol exposure and neurotoxic drugs.

Literature review

Methods

Objective

We sought to characterize the spectrum of neuropathies associated with all TNF-inhibitor therapies.

Rationale

The wide spectrum of neuropathies associated with TNF-inhibitor therapies may cause severe neuropathic pain and weakness, and if not promptly recognized, can be associated with irreversible morbidity. In 2008, Stübgen [2] provided a comprehensive literature review on the peripheral neuropathies associated with TNF-inhibitor therapy. A striking finding was that Stübgen identified TNF-inhibitor-associated neuropathies associated with all classes of TNF-inhibitors and reported such neuropathies occurring in patients other than those with RA, including psoriasis as well as inflammatory bowel disease. Subsequently, the BIOGEAS project assimilated these studies with an updated review of the literature evaluated up to July 2009, which is an ongoing multi-center study that reviews the literature and reports on inflammatory syndromes associated with TNF-inhibitor therapy [3]. The BIOGEAS project similarly defined neuropathies associated with all classes of TNF-inhibitors, and occurring in a wide variety of inflammatory syndromes. However, the BIOGEAS project has not reported on a systematic review of the literature since July 2009. In this period, the rationale for earlier initiation of TNF-inhibitors has been emphasized. Therefore, to reflect such changes since July 2009, we desired to update and define the presentation, severity, and spectrum of TNF-inhibitor-associated peripheral neuropathies.

Search criteria

We investigated the PUBMED, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, and CENTRAL (Cochrane Collaboration) databases. We did not find additional articles in other search engines beyond those identified in PUBMED.

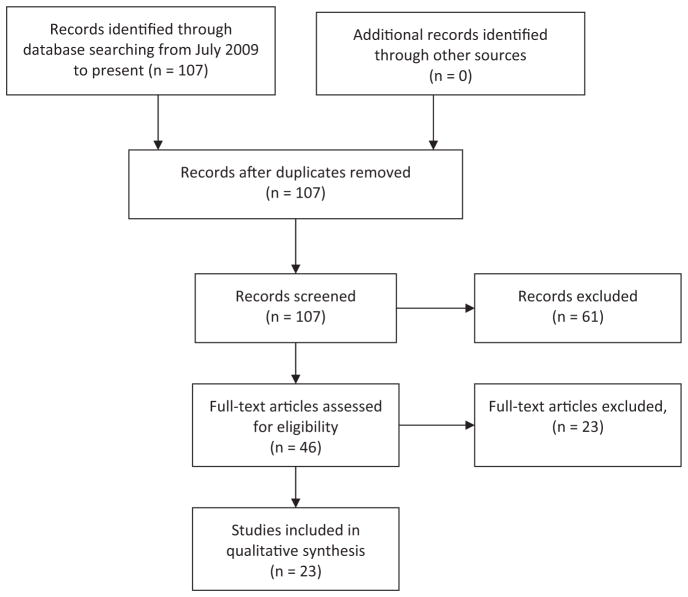

We used the similar search terms and protocol used by the BIOGEAS project to ensure that similar to the purpose of BIOGEAS we could capture neuropathies associated with all classes of TNF-inhibitors and occurring in RA as well as other inflammatory syndromes. This included the search terms of “anti-TNF,” “infliximab, ” “etanercept,” and “adalimumab,” used in combination with the terms “neuropathy,” “demyelination,” and/or “neurological disease.” Pertinent articles were reviewed. A PRISMA flow diagram is used to detail the data-gathering process (Fig. 1). We then provide a summary of the literature by integrating our literature search (after July 2009), with the findings reported by Stübgen and the BIOGEAS project (before July 2009).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA statement for identification of TNF-inhibitor-associated neuropathies used in PUBMED. As described in the text, no further articles were identified using the other specified search engines.

Patient vignettes

Patient 1

A 32-year-old Caucasian female with a history of seropositive RA (rheumatoid factor positive, anti-CCP negative) was referred for the evaluation of burning pain in the feet which was associated with infliximab therapy (Table 1, patient 1).

Table 1.

Demographic features, clinical characteristics, and skin biopsy findings in patients with small-fiber neuropathies associated with TNF-inhibitor therapy

| Variables | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at evaluation, years | 32 | 73 | 55 |

| Age of rheumatic disease onset, years | 29 | 71 | 47 |

| Ethnicity, sex | Caucasian, female | Caucasian, female | Caucasian, female |

| Prior disease-modifying agents | Hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, and methotrexate, etanercepta | Hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, and methotrexate | Hydroxychloroquine and methotrexate |

| TNF-α inhibitor at time of onset of neuropathy | Infliximab | Infliximab | Infliximab |

| Neuropathic pain distribution | Distal feet | Face and upper extremities | Face, posterior torso, and proximal lower extremities |

| Skin biopsy findings indicative of DRG versus axonal degenerationb | Abnormal skin biopsy at the distal leg indicative of distal-most axonal degeneration | N/A | Abnormal skin biopsy at the proximal thigh indicative of proximal-most DRG degeneration |

| Neurological diagnosis | Length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy | Non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy | Non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy |

| Time elapsed between onset of TNF-α inhibitor and onset of small-fiber neuropathy | 24 weeks | 18 weeks | 5 years |

| Temporal evolution of neuropathy | Acute (2 weeks) | Acute (hours) | Acute (hours) |

| Active joint disease during onset of neuropathic pain | No | No | No |

| Antibodies and titers associated with TNF-inhibitor-associated small-fiber neuropathies | ANA (1:640), homogeneous | ANA (1:1280), anti-dsDNA (1:320), anti-histone | ANA (1:160), homogenous |

| Induction of TNF-inhibitor-induced rheumatic syndrome | No | Yes, TNF-induced SLE syndrome, with malar rash and interface dermatitis | No |

| Initial requirement for poly-symptomatic therapy (≥3 medications) for neuropathic pain | Yes, including narcotics | Yes, including narcotics | Yes, including narcotics |

| Severity of neuropathic pain (VAS) associated with small-fiber neuropathy | 10/10 | 10/10 | 10/10 |

| Symptomatic response and associated treatment after withdrawal of TNF-inhibitor therapy | Gabapentin monotherapy (reduction of pain to 4/10 VAS) | Gabapentin monotherapy (reduction of pain to 4/10 VAS) | Gabapentin monotherapy (reduction of pain to 3/10 VAS) |

| Time from withdrawal of TNF-inhibitor therapy until improvement of symptoms | Over 12 months | Over 12 months | Over 12 months |

The patient was treated with etanercept for 6 months but continued to have an ongoing polyarthritis. As indicated in the text, she was transitioned to infliximab, which was associated with resolution of polyarthritis but also with development of a small-fiber neuropathy.

As noted in the text, patient 2 did not have a skin biopsy, because of the lack of any normative values of intra-epidermal nerve fiber densities from the upper extremities and the face. As discussed, such patients are clinically characterized as having a small-fiber neuropathy/ganglionopathy.

Her RA was diagnosed 3 years prior to evaluation at our Center. In the year following her diagnosis, she had persistent joint pain and swelling that symmetrically affected her elbows, wrists, hands, and ankles and was unresponsive to hydroxychloroquine 400 mg per-orally once per day (PO Qd), sulfasalazine 1000 mg per-orally twice per day (PO BID), and methotrexate at 20 mg PO once weekly.

Two years prior to evaluation at our Center, non-biological DMARDs were withdrawn, and treatment was initiated with once weekly etanercept at 50 mg subcutaneously each week. After 6 months, she still experienced persistent joint pain and swelling. Etanercept was discontinued, and infliximab was initiated at 3 mg/kg, administered at week 0, week 2, and week 6, and then increased to 5 mg/kg administered at 6-week intervals. She had resolution of joint pain after her fourth infliximab infusion (i.e., after 3 months).

However, after her sixth infliximab infusion (i.e., at week 24), she acutely over 2 weeks developed burning pain, symmetrically affecting both feet in a “length-dependent” distribution, which notably occurred in the absence of joint pain or swelling. The infliximab was discontinued, but over the following 2 months, she continued to complain of persistent burning pain in the feet. She had recurrent polyarthritis, and treatment with leflunomide at 20 mg PO Qd was initiated. Although there was resolution of her synovitis over 8 weeks, the intensity of her neuropathic pain was unchanged, described as a 10 of 10 on a Visual Analog Scale (VAS), and required a poly-symptomatic regimen that included MS Contin, gabapentin, and duloxetine. Therefore, 6 months after discontinuation of the infliximab, she was referred to our Center for further evaluation.

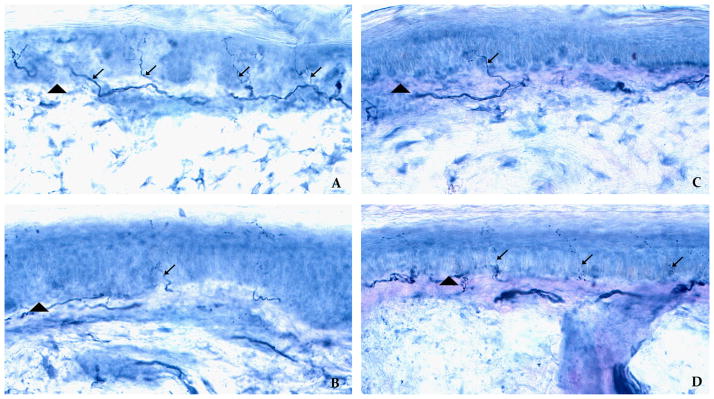

Upon evaluation at our Center, there was no joint pain or synovitis. Her neurological evaluation was consistent with a length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy. Skin biopsy confirmed a length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy with associated surrogate markers of distal-most axonal degeneration (Fig. 2A and B). Specifically, there was decreased intra-epidermal nerve fiber density restricted only to symptomatic regions of the distal leg, consistent with Wallerian degeneration affecting the distal-most axons.

Fig. 2.

Skin biopsies distinguishing between length-dependent versus non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathies in patients treated with TNF-inhibitor therapy. (A) and (B) illustrate the skin biopsy obtained from patient 1 with a length-dependent, small-fiber neuropathy. In contrast (C) and (D) illustrate the skin biopsy taken from patient 3 with a non-length-dependent, small-fiber neuropathy. The arrowheads demarcate the epidermal–dermal border, and the arrows indicate unmyelinated nerves that are immunostained against the panaxonal marker PGP 9.5. The top row refers to skin biopsy sites taken from the proximal thigh, and the bottom row refers to biopsy sites from the distal leg. In patient 1 with a length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy, there is decreased intra-epidermal nerve fiber density in the distal leg (Fig. 2B), compared to the proximal thigh (Fig. 2A). In contrast, in patient with a non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy, there is the opposing pattern with virtual absence of unmyelinated nerves in the proximal thigh (Fig. 2C), but with normal intra-epidermal nerve-fiber density in the distal leg (Fig. 2D).

Serological studies now revealed antinuclear antibodies (ANA) present at a titer of 1:640, no antibodies against extractable nuclear antigens, no anti-dsDNA antibodies, and no other evidence of TNF-induced lupus. Over the ensuing year after infliximab was discontinued, her neuropathic pain considerably improved, described as only a 4/10 on a VAS, and was able to be mono-symptomatically treated with gabapentin at 900 mg PO TID.

Patient 2

A 73-year-old Caucasian female with a history of seronegative RA was referred for evaluation of diffuse burning pain associated with infliximab therapy.

Two years prior to evaluation at our Center, she was diagnosed with RA when she presented with joint pain and swelling symmetrically affecting the wrists, hands, and knees. Initial serological evaluation did not reveal ANA or anti-dsDNA antibodies. In the ensuing 6 months following her diagnosis, she had ongoing polyarthritis, which persisted despite treatment with hydroxychloroquine 400 mg PO Qd, sulfasalazine 500 mg PO BID, and methotrexate at 20 mg once per week. Therefore, these non-biological DMARDs were withdrawn, and treatment with infliximab was initiated at 3 mg/kg, administered at week 0, week 2, and week 6, and then increased to 6 mg/kg at subsequent 6-week intervals. She had resolution of joint pain and swelling after the fourth infliximab infusion (i.e., at week 12).

However, after the fifth infliximab infusion (i.e., at week 18), she developed over a period of hours the abrupt onset of burning pain affecting her entire face and the hands up to the forearms. Her neuropathic pain was described as a 10/10 on a VAS and required a poly-symptomatic regimen that included gabapentin, pregabalin, and narcotics (MS Contin and a transdermal fentanyl patch). Because her RA continued to be clinically quiescent, and because the infliximab was not thought to be related to her neuropathic pain, infliximab was continued.

However, after the sixth infusion of infliximab (and after a cumulative exposure of 24 weeks), she then developed a malar rash, as well as an interdigital dermatitis with biopsy revealing an interface dermatitis. In addition, serological studies now revealed the presence of ANA antibodies at a titer of 1:1280 in a speckled pattern, anti-dsDNA antibodies at a titer of 1:320, and anti-histone antibodies. She was therefore diagnosed with a TNF-induced lupus syndrome. There was no alopecia, aphthous ulcerations, serositis, hematuria, or proteinuria. The infliximab was discontinued, and hydroxychloroquine at 400 mg per day was initiated.

In the ensuing 6 months after discontinuation of infliximab, the malar rash and interdigital dermatitis resolved. She had episodic joint pain and swelling affecting her wrists and hands, which was treated with and responded to prednisone at doses ranging from 5 mg PO Qd to 20 mg PO Qd. The patient did not wish to be treated with any other DMARDs, but still continued to experience neuropathic pain.

Therefore, 18 months after the onset of neuropathic pain, she was referred to our Center. At time of evaluation, there was no synovitis, malar rash, or interdigital dermatitis. She continued to report neuropathic pain in the face, hands, and forearms, although this had gradually improved since discontinuation of infliximab. Her neurological examination was consistent with a non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy. She had selective deficits to pinprick and temperature in a “non-length” dependent distribution, which involved symptomatic regions of the face, hands, and proximal forearms, but which spared the distal-most feet. Skin biopsies of the affected symptomatic regions involving the face and the upper extremity could not performed, owing to cosmetic concerns and because normative values of intra-epidermal nerve fiber density have only been established in the lower extremities and not in her symptomatic regions of the upper extremities. Therefore, similar to previously reported patients with this distribution of pain, she was therefore clinically diagnosed as having a non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy.

When evaluated over the ensuing year, the severity of neuropathic pain continued to gradually improve after withdrawal of infliximab, and could now be managed mono-symptomatically with gabapentin at 300 mg PO TID. The prednisone was titrated to and maintained at 5 mg PO Qd, with no observation of recurrent joint swelling, malar rash, or interdigital dermatitis.

Patient 3

A 55-year-old Caucasian female with a history of seronegative RA was referred for evaluation of diffuse burning pain associated with infliximab therapy.

Her RA was diagnosed 8 years prior to evaluation at our Center, when she developed a symmetric polyarthritis affecting the wrists and hands, which was initially treated with but only intermittently responsive to prednisone 10 mg PO Qd, hydroxychloroquine 400 mg PO Qd, and methotrexate 15 mg PO Q per week. Therefore, 5 years prior to evaluation at our Center, infliximab was initiated at a dose of 5 mg/kg, administered every 6 weeks. She had resolution of joint pain and swelling within 3 months of infliximab initiation.

After 5 years of infliximab therapy, she acutely developed diffuse burning pain within 24 h of an infliximab infusion. While taking a shower, she abruptly developed burning neuropathic pain that explosively occurred over the span of only 5 min. This initially affected the interscapular region, and after 6 h, diffusely spread and affected her face and proximal thighs but spared her distal feet. The severity of neuropathic pain was described as a 10 of 10 on a VAS and was intractable to a changing, poly-symptomatic regimen that included different narcotic medications. However, given that she had no evidence of joint pain or swelling, and given that the infliximab infusion was initially not thought to be related to her neurological symptoms, the infliximab was initially continued. Instead, cyclophosphamide at 150 mg PO Qd was prescribed for concern that this represented an RA-associated vasculitis, despite the absence of any RA disease activity or damage, and even though there was no stigmata of a vasculitis. The patient had ongoing neuropathic pain after 2 months of cyclophosphamide treatment. Treatment with infliximab and cyclosphophamide was then discontinued, and she was referred for further evaluation.

Upon evaluation at our Center, she had no joint pain or synovitis. Similar to the second patient, her neurological examination was consistent with a non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy. She had selective deficits to pinprick and temperature in the symptomatic regions of the face, posterior torso, and proximal lower extremities, and had normal sensation in the asymptomatic, distal feet. Skin biopsy confirmed a non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy with associated surrogate markers of proximal-most DRG neuronal degeneration. Specifically, there was decreased intra-epidermal nerve fiber density of unmyelinated nerves restricted to the proximal thigh, but with normal intra-epidermal nerve fiber density at the distal leg (Fig. 2C and D). This pattern of abnormal skin biopsy limited to the proximal thigh is mechanistically consistent with neuronal degeneration of the proximal-most DRG. Serological studies revealed ANA antibodies present at a titer of 1:160 with no anti-dsDNA antibodies, and with no evidence of lupus disease.

When evaluated over the subsequent 12 months, after discontinuation of the infliximab, she experienced a gradual but significant reduction in the intensity of pain. The severity of her neuropathic pain decreased from a VAS of 10/10 to a 3/10, and her neuropathic pain medications were able to be consolidated to a monosymptomatic regimen of gabapentin 200 mg PO TID. Because of persistent polyarthritis, treatment with leflunomide at 10 mg PO Qd was started (after neuropathic pain was improving), which led to resolution of joint pain and swelling.

Results

Clinical features, skin biopsy findings, and immunological characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the distribution of pain, neurological examination, and response to withdrawal of therapy. Patient 2 and patient 3 had a non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy, with neuropathic pain occurring in distributions not conforming to a traditional “stocking-and-glove” distribution. Specifically, the face, torso, upper extremities, or proximal thighs were affected. Such a non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy has been interchangeably referred to as a “ganglionopathy,” reflecting the DRG as the anatomic target. Skin biopsy provided further evidence that the proximal-most DRG was being targeted, with patient 3 having decreased intra-epidermal nerve fiber density restricted to the proximal thigh.

As noted above, such abnormal skin biopsy at the proximal thigh is a surrogate feature of proximal-most DRG neuronal degeneration.

In contrast, patient 1 developed an opposing pattern of a length-dependent neuropathy restricted to the distal feet. Skin biopsy revealed decreased intra-epidermal nerve fiber density restricted to the distal lower extremity, which is a surrogate feature of distal-most axonal as opposed to DRG neuronal degeneration.

Interestingly, patient 2 developed a non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy in the context of a TNF-inhibitor-induced lupus syndrome. Within six weeks of developing a small-fiber neuropathy, the patient developed a malar rash, an interdigital dermatitis with biopsy showing an interface dermatitis, with cutaneous manifestations associated with seroconversion to ANA, anti-dsDNA antibodies, and anti-histone antibodies. Both the severity of neuropathic pain and these SLE-associated cutaneous manifestations improved upon withdrawal of TNF-inhibitors.

No patients had any evidence of PNS disease prior to initiation of TNF-inhibitor therapy. All patients developed small-fiber neuropathies in the context of TNF-induced remission of disease activity and absence of disease damage. In contrast, other neuropathies described in RA patients, which are attributable to underlying RA (i.e., not iatrogenically induced), occur in the context of highly active RA or long-standing disease damage [17]. All patients initially had severe neuropathic pain, unanimously described as a 10/10 on a VAS. A notable feature is that all patients developed acute onset of neuropathic pain, with both patient 2 and patient 3 even developing neuropathic pain developing over minutes to hours. Such a rapid onset of neuropathic pain in “idiopathic” small-fiber neuropathies is highly uncharacteristic, in which neuropathic pain usually evolves more chronically. All patients had gradual improvement of neuropathic pain upon cessation of TNF-inhibitor therapy, in which poly-symptomatic therapy (which could include narcotics) was consolidated to mono-symptomatic regimens.

Patient 2 developed a small-fiber neuropathy 18 weeks after initiation of infliximab; patient 1 developed neuropathic pain 24 weeks after initiation of infliximab; whereas patient 3 developed neuropathic pain 5 years after initiation of infliximab. Despite this comparatively longer time which elapsed between onset of TNF-inhibitor and neuropathic pain, studies have shown that neuropathies attributable to TNF-inhibitor therapy can occur between 3 and 7 years after onset of TNF-inhibitor therapy [18–22]. Instead, patient 3 shared with patient 2 several unique and overlapping features that strongly suggest attribution to TNF-inhibitor therapy. Such features include the hyper-acute development of neuropathic pain that explosively occurred over minutes in patient 3 and over hours in patient 2. Furthermore, both patients had the development of neuropathic pain during TNF-inhibitor-induced remission of RA disease and the improvement of neuropathic pain upon withdrawal of TNF-inhibitor therapy.

All patients developed a small-fiber neuropathy on infliximab therapy. Patient 1 had previously been treated with etanercept for 6 months, without developing any peripheral nervous system complications.

Literature review

Results of literature review

Prior to July 2009, Stübgen [2] and the BIOGEAS project reported on 40 cases of neuropathies in patients treated with TNF-inhibitor therapy (Table 3 of [3]) [4]. We performed a systematic review of the literature, and subsequent to July 2009, identified 48 additional patients with TNF-inhibitor-associated neuropathies. Therefore, we altogether describe a total of 88 patients in the literature reported as developing neuropathies while being treated with TNF-inhibitor therapy. In reporting on this literature, we have characterized the specific subtypes of neuropathies, identified the underlying inflammatory disease and type of TNF-inhibitor therapy, described the use of any immunomodulatory therapies used to treat such neuropathies, and then further described clinical outcomes. We have summarized these results in Table 2, and have compared these findings to the patients described in our study.

Table 2.

Literature review of peripheral neuropathies associated with TNF-inhibitors

| Study | Disease | Peripheral neuropathy | TNF-Inhibitor | Interval between TNF-Inhibitor and onset of neuropathy | Immunomodulatory agents used in treatment of neuropathy | Extent of recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed et al. [42] | Psoriasis | Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy | adalimumab | 10 months | IVIG | Complete |

| Alentorn et al. [32] | Rheumatoid Arthritis | Unifocal Motor Neuropathy with Conduction Block | adalimumab | 8 months | IVIG | Partial |

| Alshekhlee et al. [30] | 2/2 Rheumatoid Arthritis | 2/2 Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy | 1/2 etanercept 1/2 infliximab | 2 weeks–12 months | 1/2 CS and IVIG 1/2 IVIG only | 1/2 Complete 1/2 Partial |

| Alverez-Lario et al. [29] | Rheumatoid Arthritis | Guillain–Barré Syndrome | adalimumab | 13 months | CS | Partial |

| Argyriou et al. [41] | Psoriatic Arthritis | Acute peroneal mononeuropathy | infliximab | 11 months | IVIG | Complete |

| Barber et al. [33] | Crohn’s Disease | Multifocal Motor Neuropathy with Conduction Block | infliximab | 15 months | IVIG | Complete |

| Bouchra et al. [26] | Ulcerative Colitis | Guillain–Barré Syndrome | infliximab | 6 weeks | IVIG | Complete |

| Burger et al. [39] | Crohn’s Disease | Axonal SM polyneuropathy | infliximab | 2 weeks | None | Complete |

| Carrilho et al. [34] | Crohn’s Disease | Multifocal Motor Neuropathy with Conduction Block | infliximab | 22 weeks | None | Partial |

| Cesarini et al. [27] | Crohn’s Disease | Guillain–Barré Syndrome | adalimumab | 14 weeks | IVIG, PLEX, CS | Partial |

| Faivre et al. [40] | Crohn’s Disease | Axonal SM polyneuropathy | infliximab | 3 weeks | IVIG | Partial |

| Kurmann et al. [37] | Rheumatoid Arthritis | Miller-Fisher syndrome | adalimumab | 2 weeks | CS, AZA | Partial |

| Lozeron et al. [35] | 1/5 Hidradenitis Suppurativa 1/5 Psoriatic Arthritis 1/5 Rheumatoid Arthritis 1/5 Ankylosing Spondylitis, Psoriasis 1/5 Crohn’s Disease, Ankylosing Spondylitis | 2/5 Multifocal SM neuropathy with Conduction Block 2/5 Motor neuropathy with Conduction Block 1/5 Sensory neuropathy with Conduction Block | 2/5 infliximab 1/5 adalimumab 1/5 infliximab 1/5 infliximab | 3–13 months | 2/5 IVIG 1/5 IVIG, PLEX 1/5 IVIG, CS, AZA | 2/5 Complete 1/5 Partial |

| Manganelli et al. [21] | Rheumatoid Arthritis | Guillain–Barré Syndrome | Adalimumab | 6 years | IVIG | Complete |

| Michell et al. [18] | Ulcerative Colitis & Ankylosing Spondylitis | 2/2 Unifocal Motor Neuropathy with Conduction Block | 2/2 infliximab | 22 weeks–6 years | None | 1/2 Complete 1/2 Partial |

| Nancey et al. [38] | 2/2 Crohn’s Disease | 2/2 Lewis-Sumner Syndrome | 2/2 infliximab | 22 weeks–7 months | 2/2 IVIG | 2/2 Complete |

| Naruse et al. [23] | Psoriasis | Sensory polyradiculopathy | Infliximab | 1 month | IVIG | Complete |

| Nozaki et al. [22] | 2/5 Sarcoidosis 1/5 Psoriatic Arthritis 1/5 Crohn’s Disease 1/5 Psoriasis | 3/5 Demyelinating PN 1/5 Axonal Sensory PN 1/5 Small Fiber Neuropathy | 3/5 infliximab 1/5 adalimumab 1/5 etanercept | 1 week–38 months | 1/5 IVIG, PLEX 1/5 CS 3/5 None | 1/5 NA (infliximab continued) |

| Paolazzi et al. [36] | Ankylosing Spondylitis | Multifocal Motor Neuropathy with Conduction Block | Infliximab | 8 months | None | Complete |

| Seror et al. [28] | 4/11 Rheumatoid Arthritis 5/11 Ankylosing Spondylitis 1/11 Psoriatic Arthritis 1/11 Other | 9/11 Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy 2/11 Guillain–Barré Syndrome | 7/11 infliximab 3/11 etanercept 1/11 adalimumab | 1.5–39.9 months | 8/11 IVIG 2/11 CS | 2/11 Complete 6/11 Partial |

| Sokumbi et al. [19] | 1/4 Rheumatoid Arthritis 1/4 Crohn’s Disease 2/4 Ulcerative Colitis | 2/4 Mononeuritis Mulitplex 1/4 Asymmetric PN 1/4 Dysesthesia | 2/4 infliximab 1/4 adalimumab 1/4 etanercept | 2 months–5 years | 1/4 CS, cyclophosphamide 1/4 CS, MTX 1/4 CS, AZA 1/4 CS, MM | 2/4 Complete 2/4 Partial |

| Solomon et al. [20] | 1/2 Rheumatoid Arthritis 1/2 Rheumatoid Arthritis, Crohn’s Disease | 1/2 Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy 1/2 Small Fiber Neuropathy | 1/2 infliximab 1/2 adalimumab | 2.5–4 years | 1/2 IVIG, CS, AZA | 1/2 Partial 1/2 Stable |

| Wong et al. [31] | Rheumatoid Arthritis | Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy | adalimumab | 2 years | IVIG | Complete |

AZA = Azathioprine; CS = Corticosteroid; IVIG = Intravenous Immunoglobulin; MM = Mycophenolate Mofetil; MTX = Methotrexate; NA=Distinction between partial and complete recovery not available; PLEX = Plasma Exchange; PN = Polyneuropathy; SM = Sensorimotor

A striking finding is that whereas we describe three patients with small-fiber sensory neuropathies, the entire literature going back more than a decade has only reported on 6 of 88 patients with pure sensory neuropathies [3,20,22–25]. This includes one patient with a sensory polyradiculopathy [23], another patient with a sensory mononeuropathy [24], and one patient with a sensory polyneuropathy [22]. Of three additional patients in the literature described as having a small-fiber neuropathy, two patients did not formally satisfy criteria for small-fiber neuropathy, as the presence of small-fiber symptoms and deficits was not described, and further ancillary studies were not pursued [22,25]. Only a single patient was described as having a skin biopsy-proven small-fiber neuropathy [20]. In contrast to this study, our report is unique in identifying two distinct clinico-pathological patterns of small-fiber neuropathies associated with TNF-inhibitor therapy, and which therefore allowed skin biopsy to be used not only as a diagnostic biomarker but also as a surrogate marker of DRG versus axonal degeneration.

In contrast to the small-fiber sensory neuropathies in our study, the most common neuropathies associated with TNF-inhibitors were sensorimotor neuropathies, which could cause severe weakness and demyelinating patterns of injury. When combining our review of the literature with the findings of Stübgen et al. and the BIOGEAS project [2,4], demyelinating neuropathies occurred in approximately 81% (71/88) of patients. In particular, there were 20 patients with Guillain–Barré syndrome/GBS [3,21,26–29], 19 patients with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy/CIDP [3,20,28,30,31], 21 patients with unifocal or multifocal neuropathy with conduction block [3,18,32–36], 3 patients with Miller Fisher syndrome [3,37], 4 patients with Lewis–Sumner syndrome [3,38], and 4 had demyelinating neuropathies not otherwise characterized [28]. Axonal neuropathies were less common, including 6 patients with axonal sensory or sensorimotor polyneuropathies [3,19,22,39,40]. In addition, there were 6 patients with a vasculitic neuropathy [3,19,41].

In our review of the literature after 2009, we were able to categorize the clinical outcomes of these neuropathies. Due to the enrichment of demyelinating neuropathies associated with TNF-inhibitor therapy, the majority of patients were treated with regimens used for “idiopathic” demyelinating syndromes. Consequently, there were 27% (13/48) patients treated with corticosteroids, 58% (28/48) treated with IVIG, and 6% (3/48) of patients treated with plasma exchange. As defined by the respective studies, the majority of patients demonstrated clinical response, with either partial improvement [20,27,32,34,37,40], or complete resolution of symptoms [21,23,26,31,33,36,38,39,41,42]. Although most patients developed neuropathies within weeks to two years after onset of TNF-inhibitor therapy, patients were described as developing neuropathies 3–7 years after onset of TNF-inhibitor therapy [18–22]. The TNF-inhibitor most commonly associated with neuropathies was infliximab, used in 63% (30/48) of patients, with adalimumab used in 25% (12/48) and etanercept used in 13% (6/48). Such TNF-inhibitors were used in 33% (16/48) of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, 19% (9/48) patients with sero-negative spondyloarthropathies, 31% (15/48) patients with inflammatory bowel disease, 17% (8/48) patients either with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, and in 4% (2/48) patients with sarcoidosis.

Discussion

We describe non-length-dependent and length-dependent small-fiber neuropathies as a spectrum of PNS disease previously not reported in association with TNF-inhibitor therapies. In contrast to such sensory neuropathies, our literature review reported that over the last decade approximately 95% of TNF-associated neuropathies have been sensorimotor neuropathies, with no studies reporting on two subtypes of small-fiber neuropathies. It is especially important for all clinicians who prescribe TNF-inhibitors to be aware of these distinct subsets of small-fiber neuropathies. As exemplified by patient 2 and patient 3, patients with non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathies may have a multifocal pain pattern that can affect the face, torso, and proximal extremities. Because such a pain distribution does not conform to a traditional “stocking-and-glove” pattern, such patients may be misdiagnosed as having fibromyalgia, a non-organic pain syndrome, or even psychiatric disease.

However, such non-length-dependent neuropathies have been extensively characterized in different inflammatory syndromes and target the DRG as the relevant anatomic region in the PNS [7–13]. In contrast, patient 1 illustrates that the TNF-inhibitors can also be associated with a more traditional pattern of a length-dependent neuropathy, in which distal neuropathic pain reflects Wallerian degeneration of distal-most axons.

Our findings also emphasize how all clinicians who prescribe TNF-inhibitors should be aware that skin biopsy is not only a diagnostic biomarker of a small-fiber neuropathy but also provides surrogate indicators of whether the DRG versus the distal axons are being targeted. Patient 1 with a length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy who presented with burning pain restricted to the feet had abnormal skin biopsy findings similarly restricted to the distal feet. Such abnormal skin biopsy findings at the distal feet are surrogate markers of distal-most axonal degeneration. In contrast, patient 3 with a non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy had abnormal skin biopsy finding also affecting the proximal thigh, which is a surrogate marker of proximal-most DRG neuronal degeneration.

Patient 2 also presented with clinical characteristics of a small-fiber neuropathy targeting the DRG (i.e., a “ganglionopathy”), but affecting the face and hands, which are regions not suitable for skin biopsy analysis. However, as further evidence that patient 2 had a TNF-inhibitor-associated small-fiber neuropathy that was iatrogenic and immune-mediated, this patient developed a small-fiber neuropathy in the context of TNF-induced lupus. Intriguingly, within 4 weeks of presenting with a small-fiber neuropathy, this patient developed a malar rash, an interdigital dermatitis with a biopsy showing an interface dermatitis, and seroconversion of ANA and anti-dsDNA antibodies.

Previously, central nervous system but not PNS manifestations have been reported as constituting part of the clinical spectrum of TNF-induced lupus [4]. Therefore, our report of such a non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy in the context of TNF-induced lupus represents the first example in the literature of any PNS syndrome reported in such TNF-induced SLE. In addition to axonal neuropathies [43,44], such small-fiber neuropathies are now regarded as peripheral manifestations of lupus [45,46].

Our collective findings provide indirect but suggestive evidence that the TNF-inhibitors may be playing an etiopathogenic role. First, none of our patients had symptoms of a small-fiber neuropathy prior to treatment with TNF-inhibitors. Second, it is notable that all patients developed small-fiber neuropathies in the context of TNF-induced remission of articular disease. Other peripheral neuropathies which may occur in RA patients include “large-fiber” axonal polyneuropathies (including pure sensory or sensorimotor polyneuropathies) and mononeuritis multiplex, but are instead associated with increased RA disease activity or disease damage [17]. Third, all patients had improvement of neuropathic pain upon withdrawal of the TNF-inhibitors, with all patients slowly able to be weaned from complex poly-symptomatic regimens (which included narcotics) to mono-symptomatic regimens at significantly lower doses.

There are several biologically plausible mechanisms that may account for pathologically distinct influences at the distal axons (in length-dependent small-fiber neuropathies) and DRGs (in non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathies). For example, TNF can play a dual role in both triggering but then attenuating an inflammatory response at the level of distal-most axons [2]. Therefore, dampening of this TNF-induced cascade may interfere with critical immunoregulatory responses and lead to axonal injury. Other immune-mediated mechanisms may account for selective targeting of the DRG in TNF-induced non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathies. For example, it is known that inhibition of the TNF axis can lead to the induction of multiple autoantibodies [1–4]. Therefore, antibodies that target the DRG can be posited as an interesting mechanism associated with TNF-induced non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathies. Such anti-DRG antibodies have been described in patients with neuropathies due to paraneoplastic and other inflammatory syndromes [47,48]. Other mechanisms may include apoptosis of the DRG perikaryon or axons in regions known to be enriched with TNF-receptors, decreased apoptosis of anti-neuronal specific T-cells, and other mechanisms that have been proposed in association with TNF-induced SLE and other inflammatory syndromes [49]. We also note that patient 1 was exposed to etanercept for a longer period of time than infliximab, but only developed a small-fiber neuropathy on infliximab. Further studies are now warranted to evaluate mechanisms of small-fiber neuropathies.

We acknowledge that whereas small-fiber neuropathies in patient 1 and patient 2 evolved within 6 months and 4 months, respectively, after TNF-inhibitor therapy, patient 3 did not develop a small-fiber neuropathy until 5 years after onset of TNF-inhibitor therapy. Yet we emphasize that a highly unique and dramatic feature is that both patient 2 and patient 3 developed a rapid crescendo of neuropathic pain developing over hours and occurring within 24 hours of an infliximab infusion. Such hyper-acute development of neuropathic pain is highly unusual for an “idiopathic” small-fiber neuropathy and suggests attribution to TNF-inhibitors. Furthermore, our literature review similarly identified that neuropathies and other inflammatory syndromes that even occurred after more than 5 years of TNF-inhibitor therapy could be regarded as attributable to TNF-inhibitors based on unique and discriminative clinical characteristics [18–22]. Both the explosive onset of neuropathic pain (see in patient 2 and 3) and significant pain resolution upon infliximab withdrawal (seen in all patients) therefore suggests such attribution to TNF-inhibitors. Finally, even if patient 3 developed a non-length-dependent small-fiber neuropathy unrelated to TNF-inhibitor therapy, our description of this patient is still valuable, as it emphasizes a broader spectrum of neuropathies than previously reported in RA patients.

In addition to neuropathies, there is an enlarging spectrum of other inflammatory syndromes that are being recognized as iatrogenic complications of infliximab therapy in RA patients. Such inflammatory syndromes have been extensively characterized and summarized and include SLE, antiphospholipid syndrome, sarcoidosis, and different skin lesions [3,4]. Of all the TNF-inhibitors, infliximab appears to be the most immunogenic, is associated with anti-chimeric antibodies [50], and has been reported more frequently in association with iatrogenically induced inflammatory syndromes compared to etanercept or adalimumab [2,4]. In rheumatoid arthritis, methotrexate is used in conjunction with infliximab not only to enhance therapeutic efficacy but also to reduce the likelihood of anti-chimeric antibodies. Higher doses of methotrexate may theoretically also attenuate the likelihood of an infliximab-associated inflammatory syndrome. In this regard, it is important to emphasize that in two of our patients (i.e., patient 1 and patient 2), non-biological therapies including methotrexate were withdrawn prior to initiation of infliximab therapy. These decisions were made at the discretion of the outside treating rheumatologists, and we were not involved in this therapeutic decision. Therefore, it is possible that withdrawal of methotrexate may have contributed to the emergence of small-fiber neuropathy as a complication of infliximab, especially if the small-fiber neuropathy may be associated with novel anti-neuronal antibody specificities (i.e., anti-dorsal root ganglia antibodies).

Although infliximab was associated with small-fiber neuropathy in our 3 RA patients, we note with interest a case report of a sarcoidosis patient whose small-fiber neuropathy was successfully treated with infliximab [51]. This somewhat paradoxical observation whereby infliximab may be both dually therapeutic and potentially iatrogenic for small-fiber neuropathies has actually been noted in other disorders [4]. For example, whereas TNF-inhibitors constitute highly effective biological treatment for psoriasis, there have been reports of psoriasiform lesions induced by TNF-inhibitors. Therefore, defining pathways whereby TNF-inhibitors may be both therapeutic and iatrogenic for specific disorders is an important goal.

In summary, we have characterized non-length-dependent and length-dependent small-fiber neuropathies as a spectrum of neurological disease previously unreported in association with TNF-inhibitors. This study suggests to rheumatologists, gastro-enterologists, and dermatologists how to use the neurological examination and skin biopsy studies to diagnose a small-fiber neuropathy. The prevalence of such neuropathies can now be evaluated in other patient cohorts treated with TNF-inhibitors, including other inflammatory arthropathies, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Birnbaum and Bingham are supported by an NIH P30 AR053503 grant.

References

- 1.Shin IS, Baer AN, Kwon HJ, Papadopoulos EJ, Siegel JN. Guillain–Barré and Miller Fisher syndromes occurring with tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonist therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1429–34. doi: 10.1002/art.21814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stübgen JP. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists and neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37:281–92. doi: 10.1002/mus.20924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosch X, Saiz A, Ramos-Casals M. Monoclonal antibody therapy-associated neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:165. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perez-Alvarez R, Perez-de-Lis M, Ramos-Casals M On behalf of the BIOGEAS study group. Biologics-induced autoimmune diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013;25:56–64. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32835b1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birnbaum J. Peripheral nervous system manifestations of Sjogren syndrome: clinical patterns, diagnostic paradigms, etiopathogenesis, and therapeutic strategies. Neurologist. 2010;16:287–97. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e3181ebe59f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacomis D. Small-fiber neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2002;26:173–88. doi: 10.1002/mus.10181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chai J, Herrmann DN, Stanton M, Barbano RL, Logigian EL. Painful small-fiber neuropathy in Sjogren syndrome. Neurology. 2005;65:925–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000176034.38198.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorson KC, Herrmann DN, Thiagarajan R, Brannagan TH, Chin RL, Kinsella LJ, et al. Non-length dependent small fibre neuropathy/ganglionopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:163–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.128801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gemignani F, Ferrari G, Vitetta F, Giovanelli M, Macaluso C, Marbini A. Non-length-dependent small fibre neuropathy. Confocal microscopy study of the corneal innervation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:731–3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.177303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan S, Zhou L. Characterization of non-length-dependent small-fiber sensory neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2012;45:86–91. doi: 10.1002/mus.22255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brannagan TH, 3rd, Hays AP, Chin SS, Sander HW, Chin RL, Magda P, et al. Small-fiber neuropathy/neuronopathy associated with celiac disease: skin biopsy findings. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1574–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.10.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lauria G, Sghirlanzoni A, Lombardi R, Pareyson D. Epidermal nerve fiber density in sensory ganglionopathies: clinical and neurophysiologic correlations. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:1034–9. doi: 10.1002/mus.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakkers M, Merkies IS, Lauria G, Devigili G, Penza P, Lombardi R, et al. Intraepidermal nerve fiber density and its application in sarcoidosis. Neurology. 2009;73:1142–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bacf05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joint Task Force of the EFNS and the PNS. European Federation of Neurological Societies/Peripheral Nerve Society guideline on the use of skin biopsy in the diagnosis of small fiber neuropathy. Report of a Joint Task Force of the European Federation of Neurological Societies and the Peripheral Nerve Society. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2010;15:79–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2010.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McArthur JC, Stocks EA, Hauer P, Cornblath DR, Griffin JW. Epidermal nerve fiber density: normative reference range and diagnostic efficiency. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1513–20. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.12.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devigili G, Tugnoli V, Penza P, Camozzi F, Lombardi R, Melli G, et al. The diagnostic criteria for small fibre neuropathy: from symptoms to neuropathology. Brain. 2008;131:1912–25. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal V, Singh R, Wiclaf, Chauhan S, Tahlan A, Ahuja CK, et al. A clinical, electrophysiological, and pathological study of neuropathy in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:841–4. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0804-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michell AW, Gaitatzis A, Burge J, Reilly MM, Kapoor R, Koltzenburg M. Isolated motor conduction block associated with infliximab. J Neurol. 2012;259:1758. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sokumbi O, Wetter DA, Makol A, Warrington KJ. Vasculitis associated with tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:739. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solomon AJ, Spain RI, Kruer MC, Bourdette D. Inflammatory neurological disease in patients treated with tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors. Mult Scler. 2011;17:1472. doi: 10.1177/1352458511412996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manganelli S, Rossi M, Tuccori M, Galeazzi M. Guillain–Barré syndrome following adalimumab treatment. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nozaki K, Silver RM, Stickler DE, Abou-Fayssal NG, Giglio P, Kamen DL, et al. Neurological deficits during treatment with tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists. Am J Med Sci. 2011;342:352–5. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31822b7bb8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naruse H, Nagashima Y, Maekawa R, Etoh T, Hida A, Shimizu J, et al. Successful treatment of infliximab-associated immune-mediated sensory polyradiculopathy with intravenous immunoglobulin. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20:1618–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richette P, Dieude P, Damiano J, Liote F, Orcel P, Bardin T. Sensory neuropathy revealing necrotizing vasculitis during infliximab therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2079–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarand J, Zochodne DW, Martin LO, Voll C. Neurological complications of infliximab. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1018–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouchra A, Benbouazza K, Hajjaj-Hassouni N. Guillain–Barré in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis secondary to ulcerative colitis on infliximab therapy. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28(Suppl 1):S53. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cesarini M, Angelucci E, Foglietta T, Vernia P. Guillain–Barrè syndrome after treatment with human anti-tumor necrosis factora (adalimumab) in a Crohn’s disease patient: case report and literature review. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:619. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seror R, Richez C, Sordet C, Rist S, Gossec L, Direz G, et al. Pattern of demyelination occurring during anti-TNF-a therapy: a French national survey. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:868. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alvarez-Lario B, Prieto-Tejedo R, Colazo-Burlato M, Macarrón-Vicente J. Severe Guillain–Barré syndrome in a patient receiving anti-TNF therapy consequence or coincidence. A case-based review. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1407. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alshekhlee A, Basiri K, Miles JD, Ahmad SA, Katirji B. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy associated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:723. doi: 10.1002/mus.21584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong SL, Rajabally YA. Steroid-induced inflammatory neuropathy in a patient on tumor necrosis factor-a antagonist therapy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2010;12:88. doi: 10.1097/CND.0b013e3181fd9401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alentorn A, Albertí MA, Montero J, Casasnovas C. Monofocal motor neuropathy with conduction block associated with adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis. Joint, Bone, Spine. 2011;78:536. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barber CE, Lee P, Steinhart AH, Lazarou J. Multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction block following treatment with infliximab. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1778. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carrilho PEM, Araújo ACF, Alves O, Kotze PG. Motor neuropathy with multiple conduction blocks associated with TNF-alpha antagonist. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2010;68:452. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2010000300022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lozeron P, Denier C, Lacroix C, Adams D. Long-term course of demyelinating neuropathies occurring during tumor necrosis factor-alpha-blocker therapy. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:490–7. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paolazzi G, Peccatori S, Cavatorta FP, Morini A. A case of spontaneously recovering multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction blocks (MMNCB) during anti-TNF alpha therapy for ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28:993. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurmann PT, Van Linthoudt D, So AK. Miller Fisher syndrome in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28:93. doi: 10.1007/s10067-008-1017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nancey S, Bouhour F, Boschetti G, Magnier C, Gonneau PM, Souquet JC, et al. Lewis and Sumner syndrome following infliximab treatment in Crohn’s disease: a report of 2 cases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1450. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burger DC, Florin TH. Peripheral neuropathy with infliximab therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1772. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faivre A, Franques J, De Paula AM, Gutierrez M, Bret S, Aubert S, et al. Acute motor and sensory axonal neuropathy and concomitant encephalopathy during tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist therapy. J Neurol Sci. 2010;291:103–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Argyriou AA, Makridou A, Karanasios P, Makris N. Axonal common peroneal nerve palsy and delayed proximal motor radial conduction block following infliximab treatment. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahmed Z, Powell R, Llewelyn G, Anstey A. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy complicating anti TNF a therapy for chronic plaque psoriasis. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1136/bcr.08.2011.4674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Florica B, Aghdassi E, Su J, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Fortin PR. Peripheral neuropathy in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:203–11. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hanly JG, Urowitz MB, Su L, Bae SC, Gordon C, Wallace DJ, et al. Prospective analysis of neuropsychiatric events in an international disease inception cohort of SLE patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;69:529–35. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.106351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Omdal R, Mellgren SI, Goransson L, Skjesol A, Lindal S, Koldingsnes W, et al. Small nerve fiber involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: a controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1228–32. doi: 10.1002/art.10303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goransson LG, Herigstad A, Tjensvoll AB, Harboe E, Mellgren SI, Omdal R. Peripheral neuropathy in primary Sjogren syndrome: a population-based study. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1612–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.11.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lancaster E, Dalmau J. Neuronal autoantigens—pathogenesis, associated disorders and antibody testing. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:380–90. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murata Y, Maeda K, Kawai H, Terashima T, Okabe H, Kashiwagi A, et al. Antiganglion neuron antibodies correlate with neuropathy in Sjogren’s syndrome. Neuroreport. 2005;16:677–81. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200505120-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Rycke L, Baeten D, Kruithof E, Van den Bosch F, Veys EM, De Keyser F. Infliximab, but not etanercept, induces IgM anti-double-stranded DNA auto-antibodies as main antinuclear reactivity: biologic and clinical implications in autoimmune arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2192–201. doi: 10.1002/art.21190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malviya G, Salemi S, Laganà B, Diamanti AP, D’Amelio R, Signore A. Biological therapies for rheumatoid arthritis: progress to date. Biodrugs. 2013;27:329. doi: 10.1007/s40259-013-0021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoitsma E, Faber CG, van Santen-Hoeufft M, De Vries J, Reulen JP, Drent M. Improvement of small fiber neuropathy in a sarcoidosis patient after treatment with infliximab. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2006;23:73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]