Abstract

Background

Peri-operative red blood cell transfusions (RBCT) may induce transfusion-related immunomodulation and impact post-operative recovery. This study examined the association between RBCT and post-pancreatectomy morbidity.

Methods

Using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) registry, patients undergoing an elective pancreatectomy (2007–2012) were identified. Patients with missing data on key variables were excluded. Primary outcomes were 30-day post-operative major morbidity, mortality, and length of stay (LOS). Unadjusted and adjusted relative risks (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (95%CI) were computed using modified Poisson, logistic, or negative binomial regression, to estimate the association between RBCT and outcomes.

Results

The database included 21 132 patients who had a pancreatectomy during the study period. Seventeen thousand five hundred and twenty-three patients were included, and 4672 (26.7%) received RBCT. After adjustment for baseline and clinical characteristics, including comorbidities, malignant diagnosis, procedure and operative time, RBCT was independently associated with increased major morbidity (RR 1.49; 95% CI: 1.39–1.60), mortality (RR 2.19; 95%CI: 1.76–2.73) and LOS (RR 1.27; 95%CI 1.24–1.29).

Conclusion

Peri-operative RBCT for a pancreatectomy was independently associated with worse short-term outcomes and prolonged LOS. Future studies should focus on the impact of interventions to minimize the use of RBCT after an elective pancreatectomy.

Introduction

Pancreatectomy is increasingly performed for both malignant and benign indications. Post-operative mortality has decreased over the past several years, reaching levels below 5% in high-volume centres.1–4 However, morbidity remains high, with reported rates ranging from 30% to 60%.1–4 This carries significant repercussions for both patients and institutions, including delayed recovery and increased hospital costs.5

Red blood cell transfusions (RBCT) have a detrimental impact on patients, mandating the judicious use of blood products.6,7 In addition to well-known but uncommon haemolytic reactions and infection transmission risks, RBCTs have been incriminated in worse post-operative outcomes for a variety of procedures.8–11 In cancer patients, RBCTs also appear to increase recurrence and reduce survival.12–15 Several theories exist to explain those findings, including that of transfusion-related immunomodulation. RBCT can suppress immunity and create a fertile ground for complications that compromise patient's post-operative progress and recovery.16–19 Specific data on the impact of RBCT on post-pancreatectomy outcomes are limited to single institution analyses with small numbers of patients.20,21

Despite evidence-based guidelines recommending a restrictive approach to RBCT use, transfusion practices vary significantly.22–25 A large number of peri-operative RBCT are unnecessary.21,26,27 Further information is needed regarding the impact of RBCT on post-pancreatectomy outcomes to confirm the need for and devise tailored strategies to address transfusion practices.28,29

The purpose of this study was to examine the impact of RBCT on short-term outcomes after elective pancreatectomy, using the large multi-institutional American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) dataset.

Patients and methods

Study design and population

A retrospective, cohort study was conducted using the ACS-NSQIP dataset. Using the ACS-NSQIP Participant User File (PUF), patients from participating institutions entered in the registry between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2012, who underwent a pancreatectomy (Current Procedural Terminology – CPT – codes 48140, 48145-6, 48150, 48152-4, 48144 and 48160) were considered eligible for the study. Additional exclusion criteria included an emergent operation, age <18 years old, or data missing on the following key variables, because of their clinical relevance in assessing outcomes of peri-operative RBCT: gender, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, pre-operative haematocrit level and cardiovascular comorbidities (cardiac heart failure, myocardial infarction, angina and hypertension).

There was no missing data on age. Missing data were encountered in < 0.05% for ASA class and gender, 2% for pre-operative haematocrit and 14% for cardiac comorbidities. Data were missing according to year of operation and increased over time. No data were missing on cardiac comorbidities for 2007–2010, whereas 24.5% were missing for this variable in 2011 and 37.1% in 2012.

Data sources

The ACS-NSQIP is a multicentre prospective registry designed to evaluate risk-adjusted outcomes of surgical patients. It includes more than 525 hospitals from academic and community settings, representative of various regions in North America. Variables collected include demographics, pre-operative risk factors, procedural indication and details, and 30-day post-operative morbidity and mortality. Data are collected by trained data abstractors and audited for accuracy.30 The methods of ACS-NSQIP data collection and audits have previously been reported.31–34

Patients' baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and treatment-related details were abstracted from the PUF. Cardiac co-morbidities were defined as a history of congestive heart failure (in the 30 days prior to surgery), myocardial infarction (in the 6 months prior to surgery), angina (in the 30 days prior to surgery) or medicated hypertension (30 days prior to surgery). A malignant diagnosis was based on ICD-9 codes (156.X, 157.X and 209.X).35 The World Health Organization cut-off of haematocrit below 40% was used to define pre-operative anaemia.36 Peri-operative RBCT was defined as the receipt of RBCT intra-operatively or in the 72 h post-operatively.30 Owing to changes in ACS-NSQIP data coding, a dichotomous transfusion variable was created for any transfusion of one or more RBC units for 2010–2012. None of the patients were missing data on the RBCT variable.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were 30-day major morbidity and mortality. The major morbidity composite outcome was created based on the occurrence of at least one of the following: deep or organ-space surgical site infection, wound dehiscence, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, prolonged mechanical ventilation beyond 48 h, unplanned re-intubation, renal failure, sepsis, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, or cerebrovascular accident.1 Post-operative mortality was defined as death within 30 days of the operation.

Secondary outcomes included system-specific 30-day morbidity grouped into post-operative infections [superficial, deep and organ space-space surgical site infection (SSI), pneumonia, urinary tract infection, sepsis and septic shock], cardiac events (myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest), respiratory failure (prolonged mechanical ventilation beyond 48 h, unplanned re-intubation), venous thrombo-embolic events (pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis) and length of stay (LOS).30

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was first performed to assess the characteristics of transfused patients and compare them to those of not transfused patients. Unknown categories were created for missing data. Categorical data were reported as absolute number (n) and proportion (%), and continuous data as mean or median with interquartile range (IQR). Baseline patient variables and operative characteristics were compared between patients who received a transfusion and those who did not. Chi-square tests for independence were used to compare categorical variables. Normally distributed continuous data were compared using t-tests and skewed continuous data using Wilcoxon-rank sum tests.

Modified Poisson regression analysis was used to examine the association between RBCT for common dichotomous outcomes (>10%), and logistic regression for uncommon dichotomous outcomes (≤10%). LOS values were treated as count data, but the data were skewed and violated the assumptions of Poisson regression, therefore, negative binomial regression was used to study the relationship between transfusion and LOS.37 Multivariate analyses were adjusted for highly relevant clinical characteristics defined a priori – age (continuous), body mass index (BMI) (<20, 20–29, 30–39, 40+, unknown), race, ASA class, pre-operative haematocrit values (continuous), cardiac comorbidities, bleeding disorder, pre-operative International Normalized Ratio (INR) (categorized as normal, abnormal and unknown), pre-operative bilirubin (categorized as normal, abnormal and unknown), malignant diagnosis, the surgical procedure (total pancreatectomy, distal pancreatectomy and pancreatoduodenectomy) and the year of the operation and operative time (continuous). Results are reported as relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

To understand how the increased level of missing data over time impacted the results, a sensitivity analysis was restricted to patients who were operated during the timeframe with complete data (2007–2010).

Results

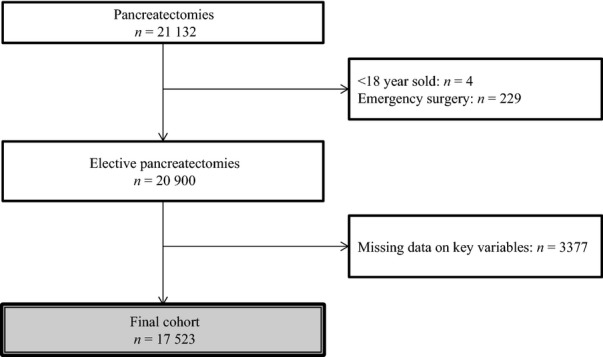

Inclusion criteria were met by 17 523 patients, of which 26.7% received an RBCT (Fig. 1). The proportion of transfused patients decreased over the years, with 29.7% in 2007 and 24.5% in 2012 (P < 0.0001). Baseline characteristics of the included patients are detailed in Table 1. Transfused patients were older (P < 0.0001), presented with a lower BMI and higher ASA score (both P < 0.0001), and had a higher burden of comorbidities, including cardio-vascular history (P < 0.0001). Transfused patients were more often operated on for malignancy (P < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patients inclusion

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included patients, based on transfusion status

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 17 523) | Transfused (n = 4672) | Not transfused (n = 12 851) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | <40 | 982 (5.6) | 184 (3.9) | 798 (6.2) | <0.0001 |

| 40–64 | 7826 (44.7) | 1904 (40.8) | 5922 (46.1) | ||

| 65–74 | 5137 (29.3) | 1432 (30.7) | 3705 (28.8) | ||

| ≥75 | 3578 (20.4) | 1152 (24.7) | 2426 (18.9) | ||

| Male gender | 8566 (48.9) | 2318 (49.6) | 6248 (48.6) | 0.2435 | |

| Race | White | 11 919 (68.0) | 3010 (64.4) | 8909 (69.3) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 1463 (8.4) | 450 (9.6) | 1013 (7.9) | ||

| Other | 515 (2.9) | 161 (3.5) | 354 (2.8) | ||

| Unknown | 3626 (20.7) | 1051 (22.5) | 2575 (20.0) | ||

| ASA Score | I | 187 (1.1) | 22 (0.5) | 165 (1.3) | <0.0001 |

| II | 5075 (29.0) | 906 (19.4) | 4169 (32.4) | ||

| III | 11 387 (65.0) | 3357 (71.9) | 8030 (62.5) | ||

| IV/V | 874 (5.0) | 387 (8.3) | 487 (3.8) | ||

| BMI | <20 | 1139 (6.5) | 357 (7.6) | 782 (6.1) | <0.0001 |

| 20–29 | 11 288 (64.4) | 2984 (63.9) | 8304 (64.6) | ||

| 30–40 | 4260 (24.3) | 1107 (23.7) | 3153 (24.5) | ||

| ≥40 | 727 (4.2) | 180 (3.9) | 547 (4.3) | ||

| Unknown | 109 (0.62) | 44 (0.94) | 65 (0.51) | ||

| Malignant diagnosis | 11 484 (65.5) | 3466 (74.2) | 8018 (62.4) | <0.0001 | |

| Diabetes | 2949 (16.8) | 1069 (22.9) | 1880 (14.6) | <0.0001 | |

| Active smoker | 3693 (21.1) | 915 (19.6) | 2778 (21.6) | 0.0037 | |

| COPD | 816 (4.7) | 257 (5.5) | 559 (4.4) | 0.0014 | |

| Dyspnea | At rest | 88 (0.5) | 41 (0.9) | 47 (0.4) | <0.0001 |

| With moderate exertion | 1398 (8.0) | 438 (9.4) | 960 (7.5) | ||

| Cardio-vascular comorbidity | 10 721 (61.2) | 3122 (66.8) | 7599 (59.1) | <0.0001 | |

| Bleeding disorder | 506 (2.9) | 207 (4.4) | 299 (2.3) | <0.0001 | |

| Corticosteroid use | 375 (2.1) | 145 (3.1) | 230 (1.8) | <0.0001 | |

| Weight loss > 10% | 2619 (15.0) | 885 (18.9) | 1734 (13.5) | <0.0001 | |

| Pre-operative haematocrit (%) | 37.9 (34.8–41.4) | 35.2 (31.5–39.0) | 38.9 (36.0–42.0) | <0.0001 | |

Values are n (%) or mean [interquartile range (IQR)].

15 481 data missing for serum albumin, 15 584 for serum bilirubin and 14 989 for INR.

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; INR, International Normalized Ratio.

The proportion of transfused patients varied according to the type of pancreatic resection, with 20.1% (n = 1110/5504) for distal pancreatectomy, 29.1% for pancreatoduodenectomy (n = 3328/11 437) and 40.2% (n = 234/582) for total pancreatectomy (P < 0.0001). The median operative time was longer in transfused than non-transfused patients, with 365 (IQR: 270–473) compared with 300 (IQR: 214–393) min (P < 0.0001).

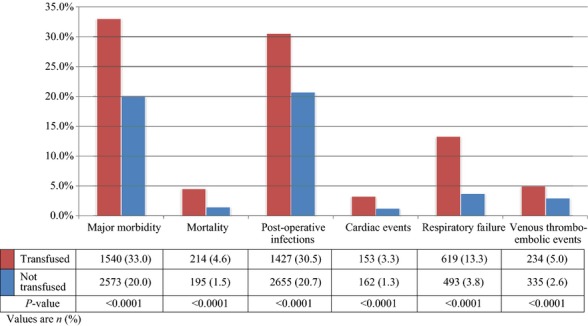

Thrity-day post-operative outcomes are detailed in Fig. 2. Overall, 23.5% of patients experienced major morbidity, and 2.3% died within 30 days of surgery. Significantly more transfused patients suffered from major morbidity and mortality. The most common complications pertained to post-operative infections.

Figure 2.

Short-term post-pancreatectomy outcomes, based on transfusion status

Results of the multivariate analysis are presented in Table 2. The adjusted risk estimates revealed that RBCT was independently associated with increased 30-day major morbidity (P < 0.0001), mortality (P < 0.0001), post-operative infections (P < 0.0001), cardiac events (P < 0.0001), respiratory failure (P < 0.0001) and venous thrombo-embolic events (P < 0.0001). After adjustment, the transfused patients experienced a prolonged LOS (RR 1.23; 95%CI: 1.17–1.29).

Table 2.

Association between RBCT and short-term post-pancreatectomy outcomes, in the entire cohort

| Outcomes | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative risk (95% CI) | P-value | Relative risk (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Major morbidity | 1.65 (1.56–1.74) | <0.0001 | 1.49 (1.39–1.60) | <0.0001 |

| Mortality | 3.12 (2.56–3.79) | <0.0001 | 2.19 (1.76–2.73) | <0.0001 |

| Post-operative infection | 1.48 (1.40–1.56) | <0.0001 | 1.37 (1.29–1.45) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac events | 2.65 (2.12–3.32) | <0.0001 | 2.26 (1.77–2.90) | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory failure | 3.83 (3.38–4.33) | <0.0001 | 2.83 (2.47–3.25) | <0.0001 |

| Venous thrombo-embolic events | 1.97 (1.66–2.34) | <0.0001 | 1.65 (1.36–2.00) | <0.0001 |

Adjusted for: age, gender, race, BMI, ASA class, HCT, bilirubin, INR, cardiac comorbidities, bleeding disorder, procedure, malignant post-operative diagnosis, and operative time.

RBCT, Red Blood Cell Transfusion; CI, Confidence Interval.

The conclusions of the analyses did not change when the cohort was restricted to calendar years with the most complete data (2007–2010).

Discussion

This analysis of the ACS-NSQIP registry examined the association between RBCT and 30-day outcomes after elective pancreatectomy, with a view to providing procedure- and practice-specific information to contribute to transfusion practices changes where needed. After adjusting for potential confounders, the risk of major morbidity and mortality were, respectively, increased approximately 1.49- and 2.19-fold for patients receiving a peri-operative RBCT. Transfused patients also had a prolonged LOS (RR 1.27; 95% CI: 1.24–1.29).

The mechanisms underlying the relationship between RBCT and worse post-operative outcomes have been the subject of various hypotheses.38 Most relate to impaired immunity through transfusion-related immunomodulation. This phenomenon appears to be multifactorial and operates by reducing natural killer cells, T cells, macrophagic and monocytic functions, and increasing the number of suppressor T cells.16 Repercussions of RBCT on the healing process after gastrointestinal anastomoses have previously been documented in pre-clinical models.39,40

Previous work has highlighted increased post-operative morbidity and mortality in general surgery patients receiving RBCT.9,41 Even small RBCT amounts as low as one unit can negatively impact outcomes, in terms of overall morbidity, sepsis or LOS.41 However, these analyses included more than 25 surgical procedures that all differ with regards to risk of transfusion and morbidity profiles. Owing to dissection close to major vascular structures, the highly vascularized nature of the pancreatic gland, and common pre-operative anaemia, pancreatic resections present a specific risk for blood loss and the need for a transfusion.42,43 The issue of RBCT is, therefore, particularly relevant to a pancreas resection and has even been suggested as a quality indicator for this procedure.44 So far, the pancreatectomy-specific evidence is limited to a few single-institution analyses with limited sample sizes.20,21 Consistent with this study, they have observed 1.5- to 2-fold higher morbidity and mortality rates with RBCT.20,21 Sets of clinical variables associated with RBCT similar to the present study were also identified, including BMI, smoking, weight loss, pre-operative haematocrit, surgical procedure and operative time.20,21 This outlines the relevance of the list confounders adjusted for in this analysis. Larger studies, some based on the ACS-NSQIP, have also been conducted, but pooled pancreatic and liver resections.26,45 Hepatectomy differs significantly from pancreatectomy by its nature, the risk for blood loss and specificities in anesthetic management.46,47 Although the current results are similar, this study adds to the literature by providing the first detailed and large-scale adjusted analysis dedicated to pancreatectomy.

The restrictive use of RBCT has repeatedly been proven safe and effective in randomized clinical trials conducted on various populations, including surgical and acutely ill patients.48–50 Documented variations in transfusion practices expose patients to unnecessary risks, impairs their recovery, increases healthcare costs and results in a waste of limited resources.7,20,25,51 Judicious use of RBCT is thus warranted. While RBCT are necessary for some cases, most are unnecessary. Previous work indicated that 46–56% of peri-operative RBCT administered in hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery are inappropriate according to current guidelines.21,23,26 Encouragingly, comprehensive restrictive transfusion initiatives comprising of patient blood management consultants, institutional guidelines and the use of alternative transfusion strategies have also been successful in reducing RBCT by 15–25% in targeted surgical procedures.52–54 In particular, a significant reduction RBCT use for elective cardiac surgery was observed across 17 United States institutions in a before and after study including over 14 000 patients. It was accompanied by a reduction in overall morbidity (odds ratio – OR 0.97; 95% CI: 0.88–1.08), mortality (OR 0.53; 95%CI: 0.37–0.74) and resource utilization.54

The main limitations of this study are inherent to its retrospective nature and the use of a large database, especially information and selection bias. The ACS-NSQIP data have the advantage of being abstracted by trained healthcare professional abstractors and being validated by audits. Its accuracy and reliability have been repeatedly shown.31–34 As previously described, patterns and impact of missing data were explored and taken into consideration in the analysis. Differences in baseline characteristics of transfused patients were indicative of how a higher degree of frailty predisposed them to receive RBCT. The analysis was adjusted for known and relevant variables associated with RBCT in robust regression models. Other limitations include the lack of some variables in ACS-NSQIP. First, cancer staging or disease severity information, including the need for venous resection, was lacking. These factors can render the resection technically more challenging and increase the risk for both a transfusion and post-operative morbidity. The type of surgical procedure and operative time were used as surrogate markers for technical complexity and corrected for. Second, clinical variables dictating the indication for RBCT were not available (e.g. pre-transfusion hemoglobin, haemodynamic parameters and symptoms). Many factors play a role in the decision to transfuse a patient, and some may contribute to increased morbidity independently of RBCT. Therefore, this analysis could not tease out the exact portion of incremental morbidity attributable to unnecessary RBCT. Similarly, determining whether RBCT was directly causative of morbidity or a response to complication remains challenging. Only RBCT administered during the first 72 h following surgery were considered. Thus, transfusion is likely to have happened prior to the complication.

When gaps between practice and guidelines exist, successful and lasting uptake of guidelines requires tailored approaches driven by practice-specific data.29,55 Owing to the unique and comprehensive data from the ACS-NSQIP, this study represents the largest multi-institutional and only specific appraisal of the impact of RBCT on post-pancreatectomy short-term outcomes, and provides results with high external validity. It provides procedure-specific evidence to raise awareness about the need to minimize the use of RBCT when they can be safely avoided for elective pancreatectomy. Stronger procedure-specific evidence to support a change in practice could be obtained with a randomized study design aimed at comparing the impact of a comprehensive blood management strategy focused on restrictive transfusion guidelines compared with traditional practice on post-pancreatectomy outcomes.

Conclusion

Peri-operative RBCT was independently associated with increased 30-day major morbidity and mortality, and a prolonged LOS in patients undergoing pancreatectomy, after adjusting for potential confounders. These data further the rationale to attempt to reduce the use of RBCT after elective pancreatectomy when they can be safely avoided. Future studies should focus on the impact of interventions to minimize the use of RBCT after elective pancreatectomy.

Funding sources

None.

Conflicts of interest

NSQIP Disclosure: The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the hospitals participating in the ACS-NSQIP are the source of the data used herein; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors.

References

- Parikh P, Shiloach M, Cohen ME, Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, Hall BL, et al. Pancreatectomy risk calculator: an ACS-NSQIP resource. HPB. 2010;12:488–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JL, Riall TS, Coleman J, Belcher KA. One thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. Ann Surg. 2006;244:10–15. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217673.04165.ea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouma DJ, van Geenen RC, van Gulik TM, de Haan RJ, de Wit LT, Busch OR, et al. Rates of complications and death after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and the impact of hospital volume. Ann Surg. 2000;232:786–795. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200012000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee JT, Hill JS, Whalen GF, Zayaruzny M, Litwin DE, Sullivan ME, et al. Perioperative mortality for pancreatectomy: a national perspective. Ann Surg. 2007;246:246–253. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000259993.17350.3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enestvedt CK, Diggs BS, Cassera MA, Hammill C, Hansen PD, Wolf RF. Complications nearly double the cost of care after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg. 2012;204:332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callum JL, Waters JH, Shaz BH, Sloan SR, Murphy MF. The AABB recommendations for the Choosing Wiselycampaign of the American Board of Internal Medicine. Transfusion. 2014;54:2344–2352. doi: 10.1111/trf.12802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association, Joint Commission. Proceedings from the National Summit on Overuse [Internet]. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/overuse_summit/ (last accessed 1 November 2014)

- OBrien SF, Yi QL, Fan W, Scalia V, Fearon MA, Allain JP. Current incidence and residual risk of HIV, HBV and HCV at Canadian Blood Services. Vox Sang. 2012;103:83–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2012.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard AC, Davenport DL, Chang PK, Vaughan TB, Zwischenberger JB. Intraoperative transfusion of 1 U to 2 U packed red blood cells is associated with increased 30-day mortality, surgical-site infection, pneumonia, and sepsis in general surgery patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:931–937. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acheson AG, Brookes MJ, Spahn DR. Effects of allogeneic red blood cell transfusions on clinical outcomes in patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2012;256:235–244. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825b35d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga M, Vignali A, Radaelli G, Gianotti L, Di Carlo V. Association between perioperative blood transfusion and postoperative infection in patients having elective operations for gastrointestinal cancer. Eur J Surg. 1992;158:531–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneuertz PJ, Patel SH, Chu CK, Maithel SK, Sarmiento JM, Delman KA, et al. Effects of perioperative red blood cell transfusion on disease recurrence and survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1327–1334. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1476-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato A, Pescatori M. Perioperative blood transfusions for the recurrence of colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD005033. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005033.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto J, Kosuge T, Takayama T, Shimada K, Yamasaki S, Ozaki H, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion promotes recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. Surgery. 1994;115:303–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojima T, Iwahashi M, Nakamori M, Nakamura M, Naka T, Katsuda M, et al. Association of allogeneic blood transfusions and long-term survival of patients with gastric cancer after curative gastrectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1821–1830. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0973-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg N, Heal JM. Effects of transfusion on immune function. Cancer recurrence and infection. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1994;118:371–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opelz G. Improved kidney graft survival in nontransfused recipients. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1987;19:149–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters WR, Fry RD, Fleshman JW, Kodner IJ, Opelz G. Multiple blood transfusions reduce the recurrence rate of Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:749–753. doi: 10.1007/BF02562122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkley SA. Proposed mechanisms of transfusion-induced immunomodulation. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:652–657. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.5.652-657.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun RC, Button AM, Smith BJ, Leblond RF, Howe JR, Mezhir JJ. A comprehensive assessment of transfusion in elective pancreatectomy: risk factors and complications. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:627–635. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2169-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A, Mohammed S, Van Buren G, Silberfein EJ, Artinyan A, Hodges SE, et al. An assessment of the necessity of transfusion during pancreatoduodenectomy. Surgery. 2013;154:504–511. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retter A, Wyncoll D, Pearse R, Carson D, McKechnie S, Stanworth S, et al. Guidelines on the management of anaemia and red cell transfusion in adult critically ill patients. Br J Haematol. 2013;160:445–464. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson JL, Grossman BJ, Kleinman S, Tinmouth AT, Marques MB, Fung MK, et al. Red blood cell transfusion: a clinical practice guideline from the AABB. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:49–58. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201206190-00429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Anesthesiology. Practice Guidelines for blood component therapy: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Blood Component Therapy. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:732–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton B, Fergusson D, Tinmouth A, McIntyre L, Kmetic A, Hébert PC. Transfusion rates vary significantly amongst Canadian medical centres. Can J Anesth. 2005;52:581–590. doi: 10.1007/BF03015766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejaz A, Spolverato G, Kim Y, Frank SM, Pawlik TM. Identifying variations in blood use based on hemoglobin transfusion trigger and target among hepatopancreaticobiliary surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:217–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank SM, Resar LMS, Rothschild JA, Dackiw EA, Savage WJ, Ness PM. A novel method of data analysis for utilization of red blood cell transfusion. Transfusion. 2013;53:3052–3059. doi: 10.1111/trf.12227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraris VA, Davenport DL, Saha SP, Austin PC, Zwischenberger JB. Surgical outcomes and transfusionof minimal amounts of blood in the operating room. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:1674–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A. Translating guidelines into practice. CMAJ. 1997;157:408–416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Surgeons. 2013. , editor. User Guide for the 2012 ACS-NSQIP Participant Use Data File. American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

- Henderson WG, Daley J. Design and statistical methodology of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: why is it what it is? Am J Surg. 2009;198:S19–S27. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen ME, Ko CY, Bilimoria KY, Zhou L, Huffman K, Wang X, et al. Optimizing ACS NSQIP modeling for evaluation of surgical quality and risk: patient risk adjustment, procedure mix adjustment, shrinkage adjustment, and surgical focus. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:336–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiloach M, Frencher SK, Steeger JE, Rowell KS, Bartzokis K, Tomeh MG, et al. Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport DL, Holsapple CW, Conigliaro J. Assessing surgical quality using administrative and clinical data sets: a direct comparison of the University HealthSystem Consortium Clinical Database and the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data set. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24:395–402. doi: 10.1177/1062860609339936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Health Organization. Manual of the internatioanl statistical classification of diseases, injuries, and causes of death (9th revision) Geneva: The World Health Organization; 1976. , editor. [Google Scholar]

- Benoist B, McLean E, Egli I. Cogswell M. 2008. , & Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993-2005: WHO global database on anaemia. Benoist B, McLean E, Egli I, Cogswell M, editors. World Health Organization Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

- Gardner W, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. Regression analyses of counts and rates: Poisson, overdispersed Poisson, and negative binomial models. Psychol Bull. 1995;118:392–404. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vamvakas EC, Blajchman MA. Transfusion-related immunomodulation (TRIM): an update. Blood Rev. 2007;21:327–348. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros T, Wobbes T, Hendriks T. Blood transfusion impairs the healing of experimental intestinal anastomoses. Ann Surg. 1992;215:276–281. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199203000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros T, Wobbes T, Hendriks T. Opposite effects of interleukin-2 on normal and transfusion-suppressed healing of experimental intestinal anastomoses. Ann Surg. 1993;218:800–808. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199312000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraris VA, Davenport DL, Saha SP, Bernard A, Austin PC, Zwischenberger JB. Intraoperative transfusion of small amounts of blood heralds worse postoperative outcome in patients having noncardiac thoracic operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:1674–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lermite E, Sommacale D, Piardi T, Arnaud J-P, Sauvanet A, Dejong CHC, et al. Complications after pancreatic resection: diagnosis, prevention and management. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig H, Van Belle S, Barrett-Lee P, Birgegård G, Bokemeyer C, Gascón P, et al. The European Cancer Anaemia Survey (ECAS): a large, multinational, prospective survey defining the prevalence, incidence, and treatment of anaemia in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2293–2306. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball CG, Pitt HA, Kilbane ME, Dixon E, Sutherland FR, Lillemoe KD. Peri-operative blood transfusion and operative time are quality indicators for pancreatoduodenectomy. HPB. 2010;12:465–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas DJ, Schexneider KI, Weiss M, Wolfgang CL, Frank SM, Hirose K, et al. Trends and risk factors for transfusion in hepatopancreatobiliary surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;18:719–728. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2417-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui LL, Smith AJ, Bercovici M, Szalai JP, Hanna SS. Minimising blood loss and transfusion requirements in hepatic resection. HPB. 2002;4:5–10. doi: 10.1080/136518202753598672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally SJ, Revie EJ, Massie LJ, McKeown DW, Parks RW, Garden OJ, et al. Factors in perioperative care that determine blood loss in liver surgery. HPB. 2012;14:236–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00433.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, Marshall J, Martin C, Pagliarello G, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409–417. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson JL, Terrin ML, Noveck H, Sanders DW, Chaitman BR, Rhoads GG, et al. Liberal of restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2453–2462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch A, Concepción M, Hernandez-Gea V, Aracil C, et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juneja R, Mehta Y. Blood transfusion is associated with increased resource utilisation, morbidity, and mortality in cardiac surgery. Ann Card Anaesth. 2008;11:136–137. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.41591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman J, Luke K, Escobar M, Vernich L, Chiavetta JA. Experience of a network of transfusion coordinators for blood conservation (Ontario Transfusion Coordinators [ONTraC]) Transfusion. 2008;48:237. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froman JP, Mathiason MA, Kallies KJ, Bottner WA, Shapiro SB. The impact of an integrated transfusion reduction initiative in patients undergoing resection for colorectal cancer. Am J Surg. 2012;204:944–950. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapar DJ, Crosby IK, Ailawadi G, Ad N, Choi E, Spiess BD, et al. Blood product conservation is associated with improved outcomes and reduced costs after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:796–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud P-AC, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]