Abstract

The interaction of tricyclic antidepressants with the human (h) α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in different conformational states was compared with that for the noncompetitive antagonist mecamylamine by using functional and structural approaches. The results established that: (a) [3H]imipramine binds to hα4β2 receptors with relatively high affinity (Kd = 0.83 ± 0.08 μM), but imipramine does not differentiate between the desensitized and resting states, (b) although tricyclic antidepressants inhibit (±)-epibatidine-induced Ca2+ influx in HEK293-hα4β2 cells with potencies that are in the same concentration range as that for (±)-mecamylamine, tricyclic antidepressants inhibit [3H]imipramine binding to hα4β2 receptors with affinities >100-fold higher than that for (±)-mecamylamine. This can be explained by our docking results where imipramine interacts with the leucine (position 9′) and valine (position 13′) rings by van der Waals contacts, whereas mecamylamine interacts electrostatically with the outer ring (position 20′), (c) van der Waals interactions are in agreement with the thermodynamic results, indicating that imipramine interacts with the desensitized and resting receptors by a combination of enthalpic and entropic components. However, the entropic component is more important in the desensitized state, suggesting local conformational changes. In conclusion, our data indicate that tricyclic antidepressants and mecamylamine efficiently inhibit the ion channel by interacting at different luminal sites. The high proportion of protonated mecamylamine calculated at physiological pH suggests that this drug can be attracted to the channel mouth before binding deeper within the receptor ion channel finally blocking ion flux.

Keywords: Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, Tricyclic antidepressants, Mecamylamine, Conformational states, Thermodynamic parameters, Molecular modeling

1. Introduction

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are a class of structurally related compounds that have been widely used to treat several depressive and anxiety mood disorders (Baldessarini, 2001). The clinical efficacy/toxicity produced by these compounds is due to a combination of inhibitory actions on different targets including, reuptake transporters for the neurotransmitters serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) and norepinephrine, muscarinic receptors, histamine H1 receptors, adrenergic α1 receptors, and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) (Baldessarini, 2001). AChRs are members of the Cys-loop ligand-gated ion channel superfamily, including types A and C γ-aminobutyric acid, type 3 5-hydroxytryptamine, and glycine receptors (reviewed in Arias, 2001, 2006; Arias et al., 2006a). The malfunctioning of these receptors has been considered as the origin of several neurological disorders (reviewed in Hogg et al., 2003). For example, depressed mood states have been associated with hypercholinergic neurotransmission (reviewed in Shytle et al., 2002). Thus, the therapeutic action of many antidepressants may be mediated, at least partially, through inhibition of this excessive neuronal AChR activity. There is an increasing amount of evidence supporting a possible role of neuronal AChRs in the process of depression as well as in the clinical activity of antidepressants. For example, a higher rate of smokers is observed in depressed patients compared with the general population (reviewed in Picciotto et al., 2002), and animal mutant results indicate that α4β2 AChRs are required for the antidepressant effect of amitriptyline (Caldarone et al., 2004). In addition, nicotine as well as competitive and noncompetitive antagonists (NCAs) (e.g., mecamylamine) potentiate the antidepressant activity of TCAs (Popik et al., 2003; Caldarone et al., 2004).

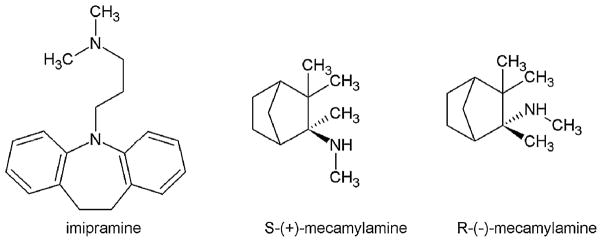

Previous studies have shown that TCAs behave as NCAs of both muscle- (Gumilar et al., 2003; Schofield et al., 1981) and neuronal-type AChRs (Rana et al., 1993; Arita et al., 1987; Izaguirre et al., 1997; Gumilar and Bouzat, 2008; Arias et al., 2010a; reviewed in Arias et al., 2006a). The noncompetitive inhibitory mechanisms elicited by TCAs on different members of the Cys-loop ligand-gated ion channel superfamily has been partially elucidated (Gumilar et al., 2003; Gumilar and Bouzat, 2008; Eisensamer et al., 2003; reviewed in Arias et al., 2006a). More recently, the TCA binding site in the Torpedo and hα3β4 AChRs has been characterized by using photolabeling (Sanghvi et al., 2008), radioligand binding and molecular dynamic approaches (Arias et al., 2010a). Considering these studies, possible roles for neuronal Cys-loop receptors as targets for the therapeutic action of TCAs can be suggested. A better understanding of the interaction of TCAs with neuronal-type AChRs in different conformational states is crucial in determining its noncompetitive inhibitory mechanisms and to develop more specific, and subsequently, safer antidepressants. In this regard, we want to determine the interaction of the most widely used TCAs including, imipramine (see molecular structure in Fig. 1), amitriptyline, and doxepin, with different conformational states of the human (h) α4β2 AChR, the most abundant neuronal-type AChR. Since mecamylamine is a well characterized NCA (Papke et al., 2001) with antidepressant-like properties (Caldarone et al., 2004), and shows a different binding location compared with that for TCAs in the hα3β4 AChR ion channel (Arias et al., 2010a), we also want to compare the interaction of TCAs with that for mecamylamine (see molecular structure in Fig. 1). To this end, we will apply structural and functional approaches including radioligand binding assays using [3H]imipramine as a probe for the TCA locus, Ca2+ influx-induced fluorescence detections, thermodynamic and kinetic measurements using non-linear chromatography, and molecular modeling and docking studies. Although this study does not intend to determine the antidepressant properties of TCAs and mecamylamine, the results from this work will pave the way for a better understanding of how these compounds interact with the hα4β2 AChR.

Fig. 1.

Molecular structure of imipramine, the archetype of TCAs, and of both mecamylamine isomers, NCAs structurally unrelated to TCAs but with antidepressant activity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

[3H]Imipramine (47.5 Ci/mmol) was obtained from PerkinElmer Life Sciences Products, Inc. (Boston, MA, USA) and stored in ethanol at −20 °C. (±)-Epibatidine was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (Buchs, Switzerland). Imipramine hydrochloride, amitriptyline hydrochloride, doxepin hydrochloride, (±)-mecamylamine hydrochloride, sodium cholate, polyethylenimine, leupeptin, bacitracin, pepstatin A, aprotinin, benzamidine, paramethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF), and sodium azide were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). (−)-Cytisine, geneticin, and hygromycine B were obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO, USA). k-Bungarotoxin (k-BTx) was obtained from Biotoxins Incorporated (St. Cloud, FL, USA). Fetal bovine serum and trypsin/EDTA were purchased form Gibco BRL (Paisley, UK). Salts were of analytical grade.

2.2. Preparation of AChR membranes from HEK293-hα4β2 cells

The used HEK293-hα4β2 cells are the same as those previously established by Michelmore et al. (2002). These cells are a clone cell line that stably expresses the hα4β2 AChR at a level of at least 4.4 pmol/mg protein over at least 30 passages. The cells were cultured in a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium containing 3.7 g/L NaHCO3, 1.0 g/L sucrose, with stable glutamine (L-alanyl-L-glutamine, 524 mg/L) and Ham’s F-12 nutrient mixture comprising 1.176 g/L NaHCO3 supplemented with 10% (by vol.) fetal bovine serum, at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 95% relative humidity. Geneticin (0.2 mg/mL) and hygromycine B (0.2 mg/mL) selection was initiated 48 h after transfection. The cells were passaged every 3 days by detaching the cells from the cell culture flask by washing with phosphate-buffered saline and brief incubation (~3 min) with trypsin (0.5 mg/mL)/EDTA (0.2 mg/mL).

To prepare HEK293-hα4β2 membranes in large quantities, our previously developed method was used (Arias et al., 2009, 2010a,b). In order to culture cells in suspension, non-treated Petri dishes (150 mm × 15 mm) were used. After culturing the cells for ~3 weeks, cells were harvested by gently scraping and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C using a Sorvall Super T21 centrifuge. Cells were re-suspended in binding saline (BS) buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4), containing 0.025% (w/v) sodium azide and a cocktail of protease inhibitors including, leupeptin, bacitracin, pepstatin A, aprotinin, benzamidine, and PMSF. The suspension was maintained on ice and homogenized using a Polytron PT3000 (Brinkmann Instruments Inc., Westbury, NY, USA), and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C. The pellet was finally re-suspended in BS buffer containing 20% sucrose (w/v) using the Polytron, and briefly (5 × 15 s) sonicated (Branson Ultrasonics Co., Danbury, CT, USA) to assure maximum homogenization. HEK293-hα4β2 membranes were frozen at −80 °C until required. Total protein was determined using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA).

2.3. Preparation of the cellular membrane affinity chromatography (CMAC) column and chromatographic system

The CMAC-hα4β2 AChR column was prepared by the immobilization of solubilized hα4β2 AChR membranes following a previously described protocol (Moaddel et al., 2005; Arias et al., 2009). hα4β2 AChR membranes were first prepared as in Section 2.2 and then solubilized in 2% (w/v) sodium cholate dissolved in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 20 μM leupeptin, 1 mM benzamidine, 2 mM MgCl2, 3 mM CaCl2, 5 mM KCl, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.2 mM PMSF. Then, 200 mg of the immobilized artificial monolayer (IAM) liquid chromatographic stationary phase (ID = 12 μm, 300 Å pore) (Regis Technologies, Inc., Morton Grove, IL, USA) was suspended in the supernatant, and the mixture was rotated at room temperature (RT) for 1 h. The suspension was dialyzed for 1 day against 1 L of 50 mM Tris–saline buffer, pH 7.4, containing 5 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, and 0.1 mM PMSF. While dialyzing, the detergent concentration decreases below the critical micelle concentration (CMC) and forces the adsorption of the membrane fragment onto the IAM stationary phase (Moaddel and Wainer, 2009). The suspension was then centrifuged at 700 × g at 4 °C and the pellet (hα4β2-IAM) was washed three times with 10 mM ammonium acetate buffer, pH 7.4. Finally, the stationary phase was packed into a HR 5/2 column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) to yield a 150 mm × 5 mm (ID) chromatographic bed, the CMAC-hα4β2 AChR column.

Finally, the CMAC-hα4β2 AChR column was attached to the chromatographic system Series 1100 liquid chromatography/mass selective detector (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with a vacuum de-gasser (G 1322 A), a binary pump (1312 A), an autosampler (G1313 A) with a 20 μL injection loop, a mass selective detector (G1946 B) supplied with atmospheric pressure ionization electrospray and an on-line nitrogen generation system (Whatman, Haverhill, MA, USA). The chromatographic system was interfaced to a 250 MHz Kayak XA computer (Hewlett–Packard, Palo Alto, CA, USA) running ChemStation software (Rev B.10.00, Hewlett–Packard).

A 10 μL sample of 10 μM imipramine was injected onto the CMAC-hα4β2 AChR column, and the drug was monitored in the positive ion mode using single ion monitoring at m/z = 280.9 [MW + H]+ ion with the capillary voltage at 3000 V, the nebulizer pressure at 35 psi, and the drying gas flow at 11 L/min at a temperature of 350 °C.

2.4. Ca2+ influx measurements in HEK293-hα4β2 cells

Ca2+ influx was determined as previously described (Michelmore et al., 2002; Arias et al., 2009, 2010a,b). These previous studies indicated that intracellular Ca2+ increases detected after stimulation of the hα4β2 AChR in the HEK293-hα4β2 cell line are solely caused via Ca2+ influx through the hα4β2 ion channel, and there is no further augmentation by voltage-gated calcium channels or intracellular Ca2+ release.

Briefly, 5 × 104 HEK293-hα4γ2 cells per well were seeded 72 h prior to the experiment on black 96-well plates (Costar, New York, USA) and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2/95% air). 16–24 h before the experiment, the medium was changed to 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in HEPES-buffered salt solution (HBSS) (130 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgSO4, 0.9 mM NaH2PO4, 25 mM glucose, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). On the day of the experiment, the medium was removed by flicking the plates and replaced with 100 μL HBSS/1% BSA containing 2 μM Fluo-4 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) in the presence of 2.5 mM probenecid (Sigma, Buchs, Switzerland). The cells were then incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2/95% air) for 1 h. Plates were flicked to remove excess of Fluo-4, washed twice with HBSS/1% BSA, and finally refilled with 100 μL of HBSS containing different concentrations of imipramine, amitriptyline, doxepin, or (±)-mecamylamine and pre-incubated for 5 min. Plates were then placed in the cell plate stage of the fluorescent imaging plate reader (FLIPR) (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). A baseline consisting of five measurements of 0.4 s each was recorded. (±)-Epibatidine (0.1 μM) was then added from the agonist plate (placed in the agonist plate stage of the FLIPR) to the cell plate using the FLIPR 96-tip pipettor simultaneously to fluorescence recordings for a total length of 3 min. The laser excitation and emission wavelengths are 488 and 510 nm, at 1 W, and a CCD camera opening of 0.4 s.

2.5. Equilibrium binding of [3H]imipramine to the hα4β2 AChR

In order to determine the binding affinity of [3H]imipramine for the hα4β2 AChR, equilibrium binding assays were performed as previously described (Arias et al., 2003, 2010a). Briefly, HEK293-hα4β2 AChR membranes (1.5 mg/mL) were suspended in BS buffer and divided into aliquots. Then, increasing concentrations of [3H]imipramine + imipramine (i.e., 0.08–1 μM) were added to each tube and incubated for 2 h at RT. Total binding was obtained in the absence of imipramine and nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 100 μM imipramine. Specific binding was calculated as total binding minus nonspecific binding. AChR-bound [3H]imipramine was then separated from free ligand by a filtration assay using a 48-sample harvester system with GF/B Whatman filters (Brandel Inc., Gaithersburg, MD), previously soaked with 0.5% polyethylenimine for 30 min. The membrane-containing filters were transferred to scintillation vials with 3 mL of Bio-Safe II (Research Product International Corp, Mount Prospect, IL), and the radioactivity was determined using a Beckman 6500 scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA).

Using the Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), binding data were fitted according to the Rosenthal-Scatchard plot (Scatchard, 1949) using the equation:

| (1) |

where the dissociation constant (Kd) for [3H]imipramine is obtained from the negative reciprocal of the slope. The specific activity of imipramine binding sites in the membrane preparation can be estimated from the x-intersect (when y = 0) of the plot [B]/[F] versus [B], where the obtained value corresponds to the number of imipramine binding sites (Bmax) per the used concentration of total proteins (1.5 mg/mL).

2.6. [3H]Imipramine competition binding experiments using hα4β2 AChRs in different conformational states

We compared the influence of imipramine, amitriptyline, and doxepine on [3H]imipramine binding to hα4β2 AChRs in different conformational states with that for the NCA (±)-mecamylamine. In this regard, HEK293-hα4β2 AChR membranes (1.0 mg/mL) were suspended in BS buffer with 13 nM [3H]imipramine in the absence (resting/no ligand) or in the presence of 0.1 μM k-BTx (resting/k-BTx-bound state), or alternatively in the presence of 1 μM (−)-cytisine (desensitized/cytisine-bound state), and pre-incubated for 30 min at RT. Cytisine is a partial agonist that desensitizes the α4β2 AChR (Sabey et al., 1999), whereas k-BTx is a competitive antagonist member of the three-fingered neurotoxin family that maintains the AChR in the resting state (Moore and McCarthy, 1995). Considering the Kd of [3H]imipramine (see Fig. 3), nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 100 μM imipramine. The total volume was divided into aliquots, and increasing concentrations of the ligand under study were added to each tube and incubated for 2 h at RT. AChR-bound radioligand was then separated from free radioligand by the filtration assay described above.

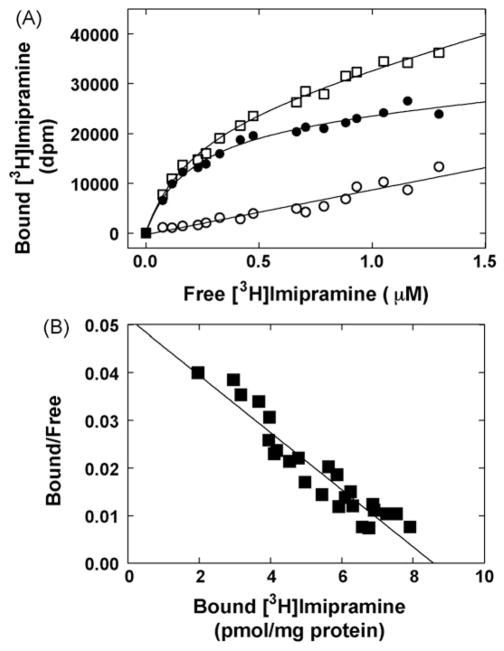

Fig. 3.

Equilibrium binding of [3H]imipramine to HEK293-hα4β2 AChR membranes. (A) total (□), nonspecific (○) (in the presence of 100 μM imipramine), and specific (●) (total – nonspecific binding) [3H]imipramine binding. hα4β2 AChR native membranes (1.5 mg/mL) were suspended in BS buffer and divided into aliquots. Then, increasing concentrations of [3H]imipramine + imipramine (i.e., 0.08–1 μM) were added to each tube and incubated for 2 h at RT. Finally, the AChR-bound [3H]imipramine was separated from the free ligand by using the filtration assay described in Section 2.5. (B) Rosenthal-Scatchard plot for [3H]imipramine specific binding to the hα4β2 AChR ion channel. The Kd value (0.83 ± 0.08 μM) was determined from the negative reciprocal of the slope, according to Eq. (1). The specific activity (8.6 ± 0.5 pmol/mg protein) of the membrane was obtained from the x-intersect (when y = 0) of the plot [B]/[F] versus [B] according to Eq. (1). Shown is the result of one out of two separate experiments.

The concentration–response data were curve-fitted by nonlinear least-squares analysis using the Prism software. The corresponding IC50 values were calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

where θ is the fractional amount of the radioligand bound in the presence of inhibitor at a concentration [L] compared to the amount of the radioligand bound in the absence of inhibitor (total binding). IC50 is the inhibitor concentration at which θ = 0.5 (50% bound), and nH is the Hill coefficient. The IC50 and the nH values obtained from the radioligand competition experiments for mecamylamine were summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Binding affinity of TCAs and (±)-mecamylamine for the [3H]imipramine binding sites at the human α4β2 AChR.

| NCA | Resting state

|

Desensitized state

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kia,b or IC50c (μM) | nHe | ΔG20f (kJ mol−1) | Kid or IC50c (μM) | nH e | ΔG20f (kJ mol−1) | |

| Imipramine | 1.1 ± 0.1a0.93 ± 0.09b | 0.73 ± 0.040.87 ± 0.07 | −33.4 ± 0.2–33.8 ± 0.2 | 0.97 ± 0.10d | 0.84 ± 0.07 | −33.7 ± 0.2 |

| Amitriptyline | 1.1 ± 0.1a | 0.98 ± 0.11 | −33.3 ± 0.3 | ND | ND | ND |

| Doxepin | 2.1 ± 0.2a | 0.73 ± 0.05 | −31.8 ± 0.3 | ND | ND | ND |

| (±)-Mecamylamine | 135 ± 19c | 0.53 ± 0.05 | ND | 209 ± 34c | 0.58 ± 0.06 | ND |

ND, not determined.

The Ki values for TCAs in the resting state were obtained in the absence (Figs. 4A,B) of k-BTx, according to Eq. (3).

The Ki values for TCAs in the resting state were obtained in the presence of k-BTx (Fig. 4A), according to Eq. (3).

The (±)-mecamylamine IC50 values were obtained in the presence of k-BTx (resting state) and in the presence of (−)-cytisine (desensitized state), from Fig. 5.

The imipramine Ki values in the desensitized state were obtained in the presence of (−)-cytisine from Fig. 4A, according to Eq. (3).

Hill coefficients.

The ΔG20 values were calculated using Eq. (4).

Taking into account that the hα4β2 AChR has one [3H]imipramine binding site (see Fig. 3), the observed IC50 values from the competition experiments described above were transformed into inhibition constant (Ki) values using the Cheng–Prusoff relationship (Cheng and Prusoff, 1973):

| (3) |

where [[3H]imipramine] is the initial concentration of [3H]imipramine, and is the dissociation constant for [3H]imipramine (0.83 μM) in the resting state (see Fig. 3). Since imipramine has practically the same affinity in the resting and desensitized states (see Table 2), the Kd value 0.83 μM (see Fig. 2) was also used to calculate the imipramine Ki value in the desensitized state. In addition, the free energy change (ΔG) for the interaction of the NCA with the receptor was determined using the following equation (reviewed in Arias, 2001):

| (4) |

where R is the gas constant (8.3145 J mol−1 K−1), and T is the experimental temperature in kelvin (293 K). The calculated Ki and ΔG values for the NCAs were summarized in Table 2.

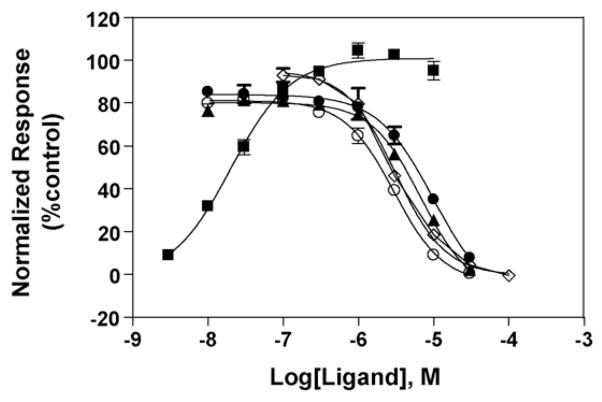

Fig. 2.

Inhibitory effect of TCAs and (±)-mecamylamine on (±)-epibatidine-induced Ca2+ influx in HEK293 cells expressing human α4β2 AChRs. Increased concentrations of (±)-epibatidine (■) activate the hα4β2 AChR with potency EC50 = 30 ± 5 nM (nH = 1.03 ± 0.04). Subsequently, cells were pre-treated with several concentrations of amitriptyline (○), imipramine (▲), doxepin (●), and (±)-mecamylamine (◇) followed by addition of 0.1 μM (±)-epibatidine. Response was normalized to the maximal (±)-epibatidine response which was set as 100%. The plots are representative of 28 (■), five (●; ○; ▲), and nine (◇) determinations, respectively, where the error bars are S.D. The calculated IC50 and nH values are summarized in Table 1.

2.7. Determination of the imipramine binding kinetics by non-linear chromatography

The binding kinetics parameters for imipramine, as the archetype of TCAs, were determined by non-linear chromatography. The details of this approach and its application to the determination of the binding kinetics of NCAs to neuronal AChRs were presented earlier (Jozwiak et al., 2004; Moaddel et al., 2007). Chromatographic elutions of imipramine from the CMAC-hα4β2 AChR column were carried out using a mobile phase composed of 10 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 7.4):methanol (85:15, v/v) delivered at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min at 20 °C.

Previous experiments indicated that upon immobilization the AChR is mainly in the resting state, and it is necessary the pharmacological action of an agonist to convert the AChR to the desensitized state (Moaddel et al., 2005). In this regard, the first set of experiments was performed in the presence of 1 nM κ-BTx (the AChR is mainly in the resting state). The CMAC-hα4β2 AChR column was equilibrated by passing the mobile phase with κ-BTx through the column for 1 h. In addition, using a fresh column, a new elution was performed in the presence of 0.1 μM (±)-epibatidine (the AChR is mainly in the desensitized state).

In the non-linear chromatography approach, concentration-dependent asymmetric chromatographic traces are observed due to slow adsorption/desorption rates. The mathematical approach used in this study to resolve these non-linear conditions was the Impulse Input Solution (Wade et al., 1987). The chromatographic data were analyzed using PeakFit v4.12 for Windows Software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) following a previously reported protocol (Jozwiak et al., 2004). Briefly, the resultant peaks were fitted to the Impulse Input Solution model by adjusting four variables, namely a0–a3. The a2 variable was directly used for the calculation of the dissociation rate constant (koff) according to this equation:

| (5) |

where t0 is the dead time of the column. The a3 value was used to calculate the association constant (Ka) for the formation of the ligand–receptor complex in equilibrium using this relationship:

| (6) |

where [ligand] is the concentration of imipramine. Both values can be used to further calculate the association rate constant kon (kon = Ka·koff).

2.8. Thermodynamic parameters of the interaction of imipramine with the hα4β2 AChR

Chromatographic elutions of imipramine from the CMAC-hα4β2 AChR column were carried out as indicated in the previous section at the following temperatures: 10, 12, 16, 20 and 25 °C. The first set of experiments was performed in the presence of 1 nM κ-BTx (the AChR is mainly in the resting state). A second set of experiments was conducted in the presence of 0.1 μM (±)-epibatidine (the AChR is mainly in the desensitized state).

The thermodynamic parameters were calculated from the chromatographic retention data at the experimental temperatures using the van’t Hoff regression equation (reviewed in Arias, 2001):

| (7) |

where ΔS° and ΔH° are the standard entropy change and standard enthalpy change, respectively. These paramaters were calculated using the slope (ΔH° = − Slope·R) and y-intersect (ΔS° = y-intersect·R) values from the plots. In addition, the entropic contribution was calculated as −TΔS°, and the free energy change at 293 K (ΔG20) was calculated using the Gibbs–Helmholtz equation (reviewed in Arias, 2001):

| (8) |

The koff values obtained using Eq. (5) were also used to construct the Arrhenius plots to determine the energy of activation (Ea) of the dissociation process, according to the Arrhenius equation (reviewed in Arias, 2001):

| (9) |

where A is the Arrhenius or pre-exponential factor, and Ea was determined from the slope of the plot (Ea = − Slope·R). In turn, the Ea values were used to calculate the enthalpy change of the transition state (ΔH+) according to the following equation (reviewed in Arias, 2001):

| (10) |

2.9. Molecular docking of imipramine and R(−)- and S(+)-mecamylamine in the hα4β2 AChR ion channel model

Since the absolute numbering of amino acid residues varies greatly between AChR subunits, the residues in the M2 transmembrane segments from the α4 and β2 subunits are referred here using the prime nomenclature (1′–20′), corresponding to residues Met243 to Glu262 of the Torpedo α1 subunit. A model of the hα4β2 AChR was constructed using homology/comparative modeling method with the Torpedo AChR structure (PDB ID 2BG9), determined at ~4 Å resolution by cryo-electron microscopy (Unwin, 2005; Miyazawa et al., 2003), as a template.

Computational simulations were performed using the same protocol as previously reported (Sanghvi et al., 2008; Arias et al., 2009, 2010a). In the first step, imipramine and both R(−)- and S(+)-mecamylamine isomers, each in the neutral and protonated state, were prepared using HyperChem 6.0 (HyperCube Inc., Gainesville, FL). Sketched molecules were optimized using the semiempirical method AM1 (Polak-Ribiere algorithm to a gradient lower than 0.1 kcal/Å/mol) and then transferred for the subsequent step of ligand docking. The Molegro Virtual Docker (MVD 2008.2.4.0 Molegro ApS Aarhus, Denmark) was used for docking simulations of flexible ligands into the rigid target AChR model. In this step the complete structures of target receptors were used. The docking space was limited and centered on the middle of the ion channel and extended enough to ensure covering of the whole channel domain for sampling simulations (docking space was defined as a sphere of 21 Å in diameter). The actual docking simulations were performed using the following settings: numbers of runs = 100; maximal number of iterations = 10,000; maximal number of poses = 10, and the pose representing the lowest value of the scoring function (MolDockScore) for imipramine and mecamylamine were further analyzed.

3. Results

3.1. Inhibition of (±)-epibatidine-mediated Ca2+ influx in HEK293-hα4β2 cells by TCAs and (±)-mecamylamine

The potency of (±)-epibatidine to activate the hα4β2 AChR was first determined by assessing the fluorescence change in HEK293-hα4β2 cells after (±)-epibatidine stimulation. The observed EC50 value (30 ± 5 nM; nH = 1.03 ± 0.04; see Fig. 2) was similar to previous determinations using cell lines expressing the α4β2 AChR (Michelmore et al., 2002; Fitch et al., 2003). (±)-Epibatidine-induced hα4β2 AChR activation is blocked by pre-incubation with the TCAs and (±)-mecamylamine (Fig. 2). The calculated potency for TCAs follows the sequence (IC50 in μM): 2.2 ± 0.6 (amitriptyline) > 5.4 ± 1.2 (imipramine) ~ 6.8 ± 1.6 (doxepin) (Table 1). These inhibitory potencies are in the same concentration range as that for (±)-mecamylamine (3.0 ± 0.7 μM; Table 1). The determined (±)-mecamylamine IC50 value was practically the same as that observed in other previous determinations using the same AChR type (Michelmore et al., 2002; Fitch et al., 2003).

Table 1.

Inhibitory potency of TCAs and mecamylamine for the human α4β2 AChR.

The fact that the nH values for TCAs are slightly higher than unity (Table 1) suggest that the blocking process mediated by these antidepressants might be produced in a cooperative manner. In turn, this suggests that TCAs interact with more than one binding site or that more than one mechanism is taking place during the AChR ion channel inhibition. For example, TCAs can inhibit several AChR subtypes by a combination of different mechanisms including, inhibition of both open and resting (closed) channels, enhancement of AChR desensitization, and/or slow open channel blockade (Gumilar et al., 2003; Gumilar and Bouzat, 2008; Sanghvi et al., 2008; reviewed in Arias et al., 2006b). In addition, the nH value for (±)-mecamylamine is closer to unity (Table 1), suggesting that this NCA inhibits the hα4β2 AChR in a non-cooperative manner. In turn, this suggests that mecamylamine interacts with one binding site in the activated hα4β2 AChR ion channel.

3.2. Equilibrium binding of [3H]imipramine to the hα4β2 AChR

In a first attempt to study the interaction of imipramine with the hα4β2 AChR ion channel, the affinity of [3H]imipramine binding to HEK293-hα4β2 AChR membranes was determined. Fig. 3A shows the total (in the absence of imipramine), nonspecific (in the presence of 100 μM imipramine), and specific (total – nonspecific) [3H]imipramine binding to hα4β2 AChR membranes in the resting/no ligand state. Fig. 3B shows the Rosenthal-Scatchard plot for this specific binding. The results indicate that the HEK293-hα4β2 membranes have a single population of [3H]imipramine binding sites of relatively high affinity (Kd = 0.83 ± 0.08 μM) and specific activity of 8.6 ± 0.5 pmol/mg protein. The observed specific activity in HEK293-hα4β2 membranes is in the same range as that obtained by [3H]epibatidine equilibrium binding (Michelmore et al., 2002).

3.3. [3H]Imipramine binding competition experiments using hα4β2 AChRs in different conformational states

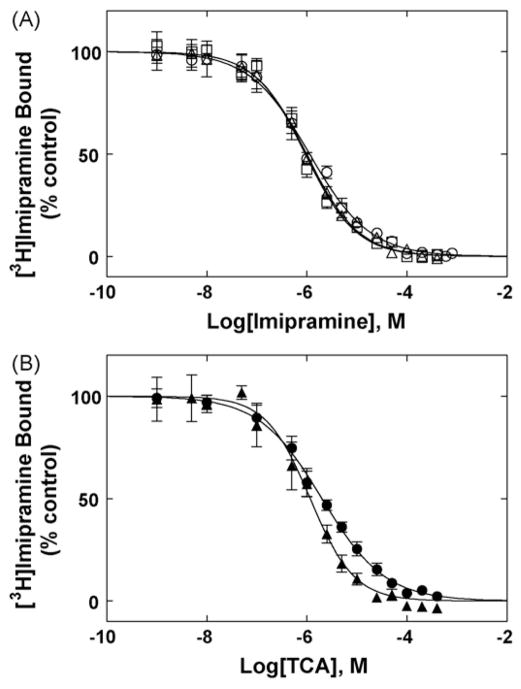

The interactions between several TCAs (i.e., imipramine, amitriptyline, and doxepin) and the hα4β2 AChR were compared with that for the NCA (±)-mecamylamine (see molecular structures in Fig. 1). In this regard, the influence of imipramine (Fig. 4) and of (±)-mecamylamine (Fig. 5) on [3H]imipramine binding to hα4β2 AChRs in the resting (in the presence or absence of k-BTx) and desensitized/cytisine-bound states were determined. Each TCA inhibits ~100% the specific binding of [3H]imipramine to the hα4β2 AChR, and the observed IC50 values for each particular receptor conformational state were very similar each other. Taking into account this pharmacological feature, the imipramine Ki value in the desensitized and resting states were calculated according to Eq. (3) using the imipramine Kd value obtained from Fig. 3. As a note of consideration, the apparent IC50 values and the calculated Ki values only differ by ~2%. Thus, by comparing the Ki values in different conformational states (Table 2), we can indicate that imipramine binds to the hα4β2 AChR ion channel in the absence of any ligand (resting/no ligand state) (1.1 ± 0.1 μM) with exactly the same affinity as in the resting/k-BTx-bound AChR (0.93 ± 0.09 μM) and desensitized/cytisine-bound AChRs (0.97 ± 0.10 μM). This suggests that imipramine does not discriminate between the desensitized and resting hα4β2 AChR conformational states. Since the binding affinity for the desensitized/cytisine-bound AChR was the same as that for the resting/k-BTx-bound AChR, we did not determine the binding affinity of amitriptyline and doxepine for the desensitized/cytisine-bound AChR. In this regard, the TCA affinity values (Kis in μM) in the resting (no ligand) state follow the sequence: imipramine (1.1 ± 0.1) ~ amitryptiline (1.1 ± 0.1) > doxepin (2.1 ± 0.2) (see Table 2). This sequence is practically the same as that obtained in the resting hα3β4 (Arias et al., 2010a) and desensitized Torpedo AChRs (Gumilar et al., 2003) by radioligand competition binding experiments. The fact that the calculated nH values are close to unity (Table 2) indicates that the TCAs inhibit [3H]imipramine binding in a non-cooperative manner. These data suggest that TCAs interact with a single binding site in the resting hα4β2 AChR ion channel or with several sites with similar affinity.

Fig. 4.

TCA-induced inhibition of [3H]imipramine binding to hα4β2 AChRs in different conformational states. (A) Imipramine-induced inhibition of [3H]imipramine binding to hα4β2 AChRs in the absence (no ligand) (○) or in the presence of 0.1 μM k-BTx (resting state) (□), or in the presence of 1 μM (−)-cytisine (desensitized state) (△), respectively. (B) Inhibition of [3H]imipramine binding to hα4β2 AChRs in the absence of ligands [no k-BTx and no (−)-cytisine] elicited by amitriptyline (▲) and doxepin (●). hα4β2 AChR membranes (1.0 mg/mL) were equilibrated (2 h) with 15 nM [3H]imipramine and increasing concentrations of the TCA under study. Nonspecific binding was determined at 100 μM imipramine. Each plot is the combination of two to three separated experiments each one performed in triplicate. From these plots the IC50 and nH values were obtained by non-linear least-squares fit according to Eq. (2). Subsequently, the Ki values were calculated using Eq. (3) and summarized in Table 2.

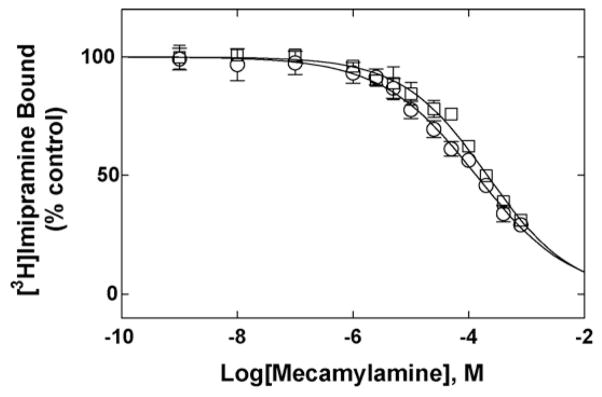

Fig. 5.

(±)-Mecamylamine-induced inhibition of [3H]imipramine binding to hα4β2 AChRs in the presence of k-BTx (○) (resting state) or in the presence of 1 μM (−)-cytisine (desensitized state) (□), respectively. hα4β2 AChR membranes (1.0 mg/mL) were equilibrated (2 h) with 15 nM [3H]imipramine and increasing concentrations of (±)-mecamylamine (i.e., 1 nM–800 μM). Nonspecific binding was determined at 100 μM imipramine. Each plot is the combination of two to three separated experiments each one performed in triplicate. From these plots the IC50 and nH values were obtained by non-linear least-squares fit according to Eq. (2), and summarized in Table 2.

In comparison, (±)-mecamylamine inhibited only ~70% [3H]imipramine binding to the hα4β2 AChR at a maximum concentration double than that for TCAs (Fig. 5). The determined IC50 values (Table 1) suggest that (±)-mecamylamine binds with extremely low affinity to the [3H]imipramine binding site when the hα4β2 AChR is in either the resting/k-BTx-bound state or desensitized/cytisine-bound state. The observed nH values are lower than unity, suggesting a negative cooperative interaction between imipramine and mecamylamine. In conclusion, it is likely that mecamylamine does not bind to the imipramine site in either AChR conformational state.

3.4. Binding kinetic parameters for imipramine determined by non-linear chromatography

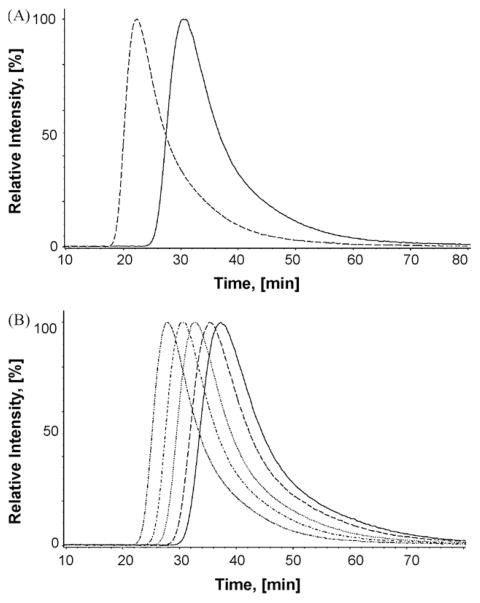

Fig. 6A shows the expected asymmetric traces for imipramine when it is chromatographed on the CMAC-hα4β2 AChR column. The data were used to determine the koff and Ka values according to Eqs. (5) and (6), respectively, and thus, to further calculate the kon values for imipramine when it binds to the hα4β2 AChR in different conformational states (see Table 3). The kinetic results indicate that imipramine binding to the AChR is not a diffusion-controlled reaction because the determined association rate constants (kon ~105 M−1 s−1) are approximately four orders of magnitude smaller than the typical values for diffusion-controlled reactions (~109 M−1 s−1). The observed decrease in the kon constants can be explained by structural and orientational constrains in the binding pocket. The results also indicate that the dissociation rate constant (koff) of imipramine was slightly slower (0.076 ± 0.002 s−1) when it is eluted from the column in the presence of (±)-epibatidine (the AChR is mainly in the desensitized state) compared to that in the presence of κ-BTx (the AChR is mainly in the resting state) (0.090 ± 0.001 s−1). This result indicates that TCAs are dissociated from the desensitized hα4β2 AChR ion channel at a slightly slower rate than that from the resting AChR ion channel.

Fig. 6.

Chromatographic elution of imipramine from the CMAC-hα4β2 AChR column. (A) Imipramine is eluted from the column with ammonium acetate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4) and 15% methanol as the mobile phase, at 0.2 mL/min and 20 °C. The dashed line represents the elution of imipramine from the CMAC-hα4β2 AChR column in the presence of κ-BTx (the immobilized AChR is mainly in the resting state), and the straight line represents the elution of imipramine from the CMAC-hα4β2 AChR column in the presence of (±)-epibatidine (the immobilized AChR is mainly in the desensitized state). (B) Imipramine is eluted from the CMAC-hα4β2 AChR column with (±)-epibatidine present in the mobile phase (predominantly desensitized state) at different temperatures (from right to left: 10, 12, 16, 20, and 25 °C).

Table 3.

Kinetic and thermodynamic parameters for imipramine binding to hα4β2 AChRs in different conformational states determined by non-linear chromatography studies.

| Parameter | κ-BTx treated columna | Epibatidine treated columnb |

|---|---|---|

| koff (s−1) | 0.090 ± 0.001 | 0.076 ± 0.002 |

| kon (s−1 μM−1) | 0.229 ± 0.008 | 0.192 ± 0.003 |

| Ka (μM−1) | 2.54 ± 0.07 | 2.52 ± 0.08 |

| ΔG20 (kJ mol−1) | −35.9 ± 0.1 | −35.9 ± 0.1 |

The koff and Ka values were empirically determined by non-linear chromatography using Eqs. (5) and (6), respectively, whereas the kon values were calculated as kon = koff·Ka. ΔG20 values were calculated using Eq. (4).

The elution of imipramine from the CMC-hα4β2 AChR column was performed in the presence of κ-BTx (the AChR is mainly in the resting state).

The elution of imipramine from the CMC-hα4β2 AChR column was performed in the presence of (±)-epibatidine (the AChR is mainly in the desensitized state).

In absolute terms, the kinetic results indicate that the drug affinity for the hα4β2 AChR (Kd = 1/Ka ~0.4 μM) corresponds very well with that obtained by [3H]imipramine competition binding experiments (Table 2). The fact that the Ka values are the same in both conformational states (Table 3) is in agreement with the radioligand binding results indicating that the imipramine binding affinity is the same either in the resting or desensitized state (Table 2).

3.5. Thermodynamic parameters for the interaction of imipramine with the hα4β2 AChR

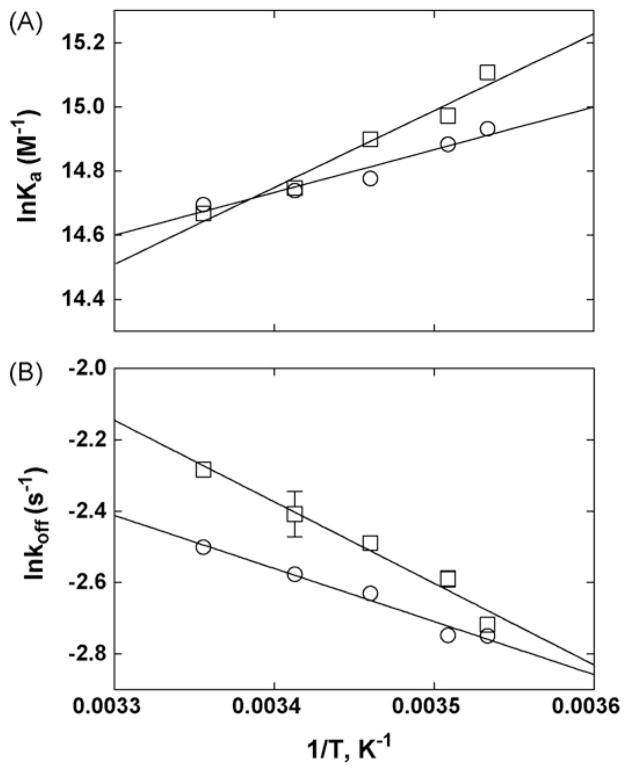

In previous studies, an increase in the temperature changed the chromatographic retention of several NCAs including dextromethorphan and levomethorphan (Jozwiak et al., 2003), and bupropion (Arias et al., 2009). In this study, non-linear chromatography was used to calculate the Ka constants [see Eq. (6)] to finally construct the van’t Hoff plots according to Eq. (7). In this regard, temperature dependent changes in imipramine retention on immobilized hα4β2 AChRs in the presence of κ-BTx (resting state) or of (±)-epibatidine (desensitized state) were obtained (Fig. 6). The resulting van’t Hoff plots were linear (Fig. 7A), indicating an invariant retention mechanism over the temperature range studied (Jozwiak et al., 2002, 2003). Consequently, the thermodynamic parameters ΔH° and ΔS° were calculated from the slopes and intercepts of the van’t Hoff plots, respectively, whereas ΔG20 was calculated according to Eq. (8) (Table 4).

Fig. 7.

(A) van’t Hoff and (B) Arrhenius plots for imipramine determined by elution from the CMAC-hα4β2 AChR column at different temperatures (see Fig. 6B). (A) van’t Hoff plots were constructed by determining the Ka values of imipramine at 10–25 °C, according to Eq. (6). The ΔH° and ΔS° values were calculated using the slope (ΔH° = − Slope·R) and y-intersect (ΔS° = −y-intersect·R) values from the plots, according to Eq. (7), where R is the gas constant (8.3145 J K−1 mol−1). (B) Arrhenius plots were constructed by determining the dissociation rate constants (koff) of imipramine at 10–25 °C, according to Eq. (5). The Ea values were calculated using the slope (Ea = − Slope·R) from the plots, according to Eq. (9). Imipramine was eluted from the column in the presence of (±)-epibatidine (○) (the AChR is mainly in the desensitized state) or κ-BTx (□) (the AChR is mainly in the resting state). The plots are the results from three experiments (n = 3), where the S.D. error bars are smaller than the symbol size. The observed r2 values for (A) are 0.962 (□) and 0.939 (○), and for (B) are 0.971 (□) and 0.975 (○), indicating that the plots are perfectly linear.

Table 4.

Thermodynamic parameters for imipramine binding to the hα4β2 AChR in different conformational states determined by non-linear chromatography.

| Thermodynamic parameters | κ-BTx treated columna | Epibatidine treated columnb |

|---|---|---|

| ΔH° (kJ mol−1) | −19.9 ± 2.3 | −11.1 ± 1.6 |

| −TΔS° (kJ mol−1) | −16.1 ± 2.3 | −24.8 ± 1.6 |

| ΔG20 (kJ mol−1) | −35.8 ± 2.9 | −35.9 ± 2.0 |

| Ea (kJ mol−1) | 19.0 ± 1.9 | 12.4 ± 1.1 |

| ΔH+ (kJ mol−1) | 16.6 ± 1.9 | 9.9 ± 1.1 |

The thermodynamic parameters ΔH° and ΔS° were calculated from Fig. 7A according to Eq. (7), and the ΔG20 values were calculated using Eq. (8). The Ea values for the process of drug dissociation were obtained from Fig. 7B, according to Eq. (9), and the ΔH+ values were calculated using Eq. (10).

The elution of imipramine from the CMC-hα4β2 AChR column was performed in the presence of κ-BTx (the AChR is mainly in the resting state).

The elution of imipramine from the CMC-hα4β2 AChR column was performed in the presence of (±)-epibatidine (the AChR is mainly in the desensitized state).

The results in the resting state indicate that the entropic (−TΔS°) and enthalpic (ΔH°) contributions for the formation of the imipramine–hα4β2 complex are practically the same, whereas the entropic contribution is ~2-fold higher (−24.8 kJ mol−1) than the enthalpic contribution (−11.1 kJ mol−1) in the desensitized state (see Table 4). This indicates that TCAs interact with the desensitized and resting AChR ion channels by a combination of enthalpic and entropic components, although the entropic component is more important in the desensitized state. In this regard, TCAs may induce local conformational changes or solvent reorganization in the binding pocket of the desensitized AChR ion channel (reviewed in Arias, 2001). Negative ΔH° values suggest the existence of attractive forces such as van der Waals, hydrogen bond, and electrostatic interactions forming the stable complex in each conformational state. The calculated ΔG20 values (Table 4) coincide very well with that determined by either radioligand (see Table 2) or kinetic (see Table 3) experiments.

Arrhenius plots [see Eq. (9)] were also constructed for imipramine at different temperatures (Fig. 7B). Since the Arrhenius plots are different from zero, the drug dissociation process is mediated mainly by an enthalpic component. To quantify this component, the Ea values were first calculated from the Arrhenius plots according to Eq. (9), and the ΔH+ values were subsequently calculated using Eq. (10) (Table 4). The fact that the Ea value in the resting state is slightly higher than that in the desensitized state indicates that the energy barrier for drug dissociation from the resting ion channel is slightly higher than that from the desensitized ion channel. This correlates well with a higher ΔH+ value in the resting state compared to that in the desensitized state.

3.6. Molecular docking of imipramine and R(−)- and S(+)-mecamylamine in the hα4β2 AChR ion channel model

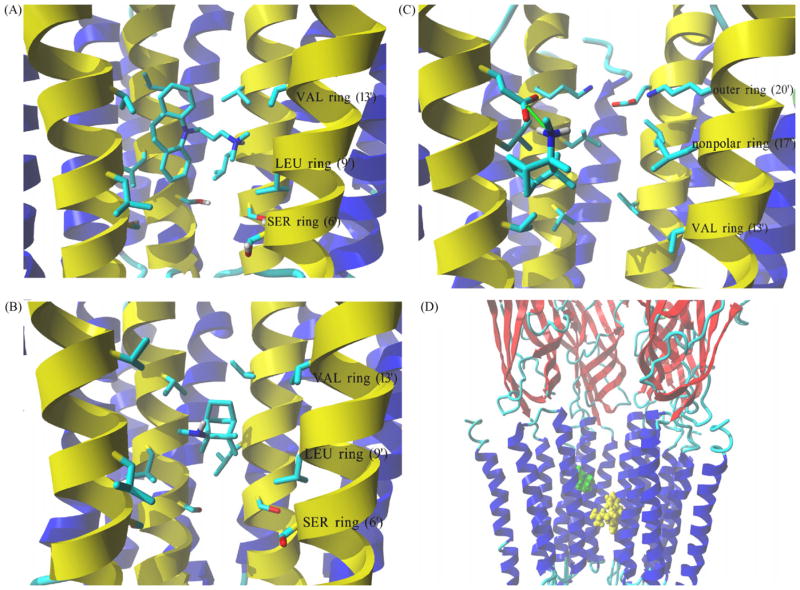

Molecular models of imipramine and both S(+)- and R(−)-mecamylamine isomers, each in either the neutral or protonated state, were docked in the hα4β2 AChR ion channel model. Molegro Virtual Docker generated a series of docking poses and ranked them using energy-based criterion using the embedded scoring function (MolDockScore) (see Table 5). Based on this ranking, the lowest energy pose of the ligand–receptor complex was selected and presented in Fig. 8. Imipramine in either ionization state interacts within the middle portion of the channel with all five M2 helices, but not with other transmembrane segments. A more detailed analysis of the docked simulation (Fig. 8A) indicates that imipramine interacts primarily with residues forming the valine (position 13′) and leucine (position 9′) rings by a network of van der Waals interactions, and no contact was observed to the serine ring (position 6′) or to the outer ring (position 20′). The imipramine molecule lays on this large surface of the ion channel, where its aromatic ring system is positioned between the α4-M2 and β2-M2 helices and its aminoalkyl tail interacts primarily with the adjacent β2-M2 helix. In addition, the charged amino group of imipramine forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone (i.e., amide groups) of the β2-M2 helix close to the leucine ring (position 9′). The mode of docking of the neutral form of imipramine molecule is essentially the same (data not shown).

Table 5.

Lowest binding energy obtained by docking of imipramine and mecamylamine isomers, respectively, with the hα4β2 AChR ion channel.

| NCA | Molecular form | MolDockScore (kJ mol−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Imipramine | Neutral | −96.0 |

| Protonated | −94.9 | |

| S(+)-mecamylamine | Neutral | −51.6 |

| Protonated | −54.0 | |

| R(−)-mecamylamine | Neutral | −51.3 |

| Protonated | –61.1 |

Molegro Virtual Docker generated a series of docking poses and ranked them using energy-based criterion using the embedded scoring function in MolDockScore. The table presents MolDockScore values calculated for the lowest energy pose for each simulation thus, no S.D. values can be provided.

Fig. 8.

Complex formed between imipramine and S(+)-mecamylamine with the hα4β2 AChR ion channel model obtained by molecular docking. (A) Interaction of the protonated imipramine molecule with the leucine (LEU) (position 9′) and valine (VAL) (position 13′) rings in the hα4β2 AChR ion channel. Imipramine interacts with the LEU and VAL rings mainly by van der Waals contacts. (B) Interaction of neutral S(+)-mecamylamine with the LEU (position 9′) and VAL (position 13′) rings in the hα4β2 AChR ion channel. S(+)-Mecamylamine interacts with the LEU and VAL rings mainly by van der Waals forces. (C) Interaction of protonated S(+)-mecamylamine with the non-polar (position 17′) and outer (position 20′) rings in the hα4β2 AChR ion channel. Green arrow indicates coulombic interactions between positively charged amino groups from the ligand and a negatively charged carboxylic group from an α4-Glu261 residue. The aliphatic portion of S(+)-mecamylamine interacts with nearby Leu residues forming the non-polar ring (position 17′). (A–C) M2 transmembrane helices forming the wall of the channel are colored yellow, all other transmembrane segments are blue. Residues from each ring are shown explicitly in stick mode. Ligand molecules are rendered in element color coded stick mode. All non-polar hydrogen atoms are hidden. (D) Side view of the lowest energy complex formed between imipramine (yellow) and S(+)-mecamylamine (green), both in the protonated state, with the hα4β2 AChR ion channel. The imipramine binding site (located between LEU and VAL rings) is clearly distinct from that found for protonated S(+)-mecamylamine (located closer to the outer ring). Receptor subunits are shown in secondary structure mode (helices, blue; β-sheets, red), and ligands are shown in ball mode. Part of the receptor extracellular portion is also shown to have a better perspective of the ligand binding site locations. For clarity one β2 subunit is hidden thus, the order of explicitly shown subunits is (from left): β2, α4, β2 and α4. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

Since mecamylamine has a chiral center, both S(+)- and R(−)-enantiomers were tested by docking to the hα4β2 AChR ion channel model. In the case of the S(+)-enantiomer, a clear distinction was observed between the interaction of the neutral and protonated molecule in the ion channel (Fig. 8). As illustrated in Fig. 8B, the neutral molecule binds to the middle portion of the channel between the valine (position 13′) and leucine (position 9) rings entirely by van der Waals interactions, without interacting with other adjacent rings. The amino group of S(+)-mecamylamine points to the center of the channel, suggesting possible interactions with water molecules. Although water molecules are not simulated explicitly during the docking experiments, the in-built algorithms take into account their effects using defined solvation parameters. Mecamylamine is a small molecule that locates between two M2 helices at the interface of the β2 and α4 subunits (Fig. 8B). Interestingly, a very different mode of binding was observed for protonated S(+)-mecamylamine (Fig. 8C). In this case, the molecule interacts with a domain close to the extracellular edge of the transmembrane domain, between the non-polar (position 17′) and outer (position 20′) rings. The most important type of interaction appears to be a coulombic attraction between the protonated amino group of S(+)-mecamylamine and the acidic α4-Glu261 residue. Both protonated and neutral R(−)-mecamylamine interact with this region as well (data not shown). The interaction of protonated R(−)-enantiomer is essentially the same as observed for protonated S(+)-mecamylamine (see Fig. 8C), whereas the unprotonated amino group of R(−)-mecamylamine forms a hydrogen bond with the same acidic residue. Thus, the simulations suggest that R(−)- and S(+)-mecamylamine predominantly interact with the extracellular mouth of the AChR ion channel.

The docking energies for imipramine and mecamylamine enantiomers, each in the neutral and protonated state, are presented in Table 5. MolDockScore values generated in the simulations for imipramine are ~40 kJ mol−1 lower than those generated during the docking of mecamylamine enantiomers. The scoring values for neutral and protonated imipramine are very similar. Protonated mecamylamine isomers generated slightly more stable complexes than that for the neutral isomers.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have shown that TCAs behave as NCAs of several AChRs (Gumilar et al., 2003; Gumilar and Bouzat, 2008; Schofield et al., 1981; Rana et al., 1993; Arita et al., 1987; Izaguirre et al., 1997; Sanghvi et al., 2008; Arias et al., 2010a; reviewed in Arias et al., 2006a). Considering these and other studies using mutant animals (e.g., see Caldarone et al., 2004), possible roles for α4β2 AChRs as targets for the therapeutical action and/or side effects elicited by TCAs can be suggested. Since the α4β2 AChR is the most abundant AChR in the CNS, a better understanding of the interaction of TCAs with this particular AChR type is crucial to determine its noncompetitive inhibitory mechanisms and to develop more specific, and subsequently, safer antidepressants. In this regard, this study is an attempt to compare the activity and binding properties of TCAs on hα4β2 AChRs in distinct conformational states. Since mecamylamine is a well characterized NCA (Papke et al., 2001; Arias et al., 2010a) with antidepressant-like properties (Caldarone et al., 2004), we also want to compare the interaction of TCAs with that for mecamylamine. To this end, radioligand binding and Ca2+ influx assays, thermodynamic and kinetic measurements, and molecular modeling and docking studies were performed. Although this study does not intend to determine the antidepressant properties of TCAs and mecamylamine, the results from this work will pave the way for a better understanding of how these compounds interact with the hα4β2 AChR.

To compare the functional effect of TCAs on (±)-epibatidine-activated Ca2+ influx in HEK293-hα4β2 cells, a pre-incubation protocol was used (Fig. 1). The results indicate that TCAs inhibit the agonist-activated hα4β2 AChR with potencies that follow the sequence: amitriptyline > imipramine ~ doxepin (Table 1). To our knowledge, this is the first experimental evidence indicating that TCAs efficiently inhibit the hα4β2 AChR. (±)-Mecamylamine also inhibits hα4β2 AChRs with potency that is in the same concentration range as that for TCAs (Table 1). The observed sequence for TCAs is practically the same as that obtained by the decrease of the duration of clusters in the muscle AChR (Gumilar et al., 2003) and by inhibition of agonist-induced hα3β4 AChR Ca2+ influx (Arias et al., 2010a). This similar structure–activity relationship suggests certain resemblance in the mechanisms of inhibition elicited by TCAs among these receptor subtypes. In this regard, additional studies are being performed in our laboratory to support this hypothesis.

The amitriptyline concentration in the rat brain at therapeutic doses has been determined to be in the 1–10 μM range (Glotzbach and Preskorn, 1982). Since the pharmacokinetic and tissue distribution properties of this drug in rodents are very similar to that in humans, the brain concentration of amitriptyline will be in the same concentration range as determined in rodents. Considering the IC50 value for amitriptyline (2.2 ± 0.6 μM) obtained in our Ca2+ influx experiments (Table 1), we can assume that the hα4β2 AChR can be inhibited, at least partially, by amitriptyline under clinical treatment. This possibility reinforces the idea that antidepressants may produce their clinical effects by inhibiting neuronal AChRs. In addition, mice lacking the β2 subunit showed neither behavioral response to amitriptyline nor increase in hippocampal cell proliferation as seen in wild-type mice (Caldarone et al., 2004). These findings support the concept that neuronal AChRs are targets for the therapeutic action of antidepressants and pave the way for the development of other antagonists for the treatment of mood disorders. The best example is the NCA mecamylamine which produces antidepressant-like activity and enhances the antidepressant activity of TCAs (Popik et al., 2003; Caldarone et al., 2004).

The results from the Scatchard-type analysis (Kd ~0.8 μM) and from the radioligand competition binding experiments (Ki ~1–2 μM) indicate that TCAs bind to a single binding site in the hα4β2 AChR with relatively high affinity. Previous [3H]imipramine binding studies in bovine adrenal medullary cells found that [3H]imipramine binds to two binding site populations with very low affinity (Kds = 13 and 165 μM, respectively), and that TCAs inhibit [3H]imipramine binding and agonist-induced 22Na+ influx with IC50 values in the 14–96 μM concentration range (Arita et al., 1987). Bovine adrenal chromaffin cells express at least two AChR types, α3β4 and α7 (see López et al., 1998, and references therein). Considering this previous attempt, the interaction of TCAs with these neuronal AChRs was predominantly of low affinity and thus, our study can be considered as the first one characterizing the interaction of TCAs with its high-affinity binding site in the hα4β2 AChR ion channel by radioligand binding methods.

The radioligand competition binding results also indicate that imipramine binds to the resting/κ-BTx-bound AChR with the same affinity as that for the desensitized/agonist-bound hα4β2 AChR (Table 2). This suggests that TCAs do not discriminate between the resting and desensitized conformational states of the hα4β2 AChR ion channel. The same result was obtained for the hα3β2 AChR (Arias et al., 2010a). Nevertheless, TCAs discriminate between the desensitized and resting Torpedo AChRs (Gumilar et al., 2003; Sangvhi et al., 2008), and serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (e.g., fluoxetine) discriminate between these two conformational states in the Torpedo (Arias et al., 2010b) and hα4β2 and hα3β4 AChRs (Arias et al., in preparation). These data suggest that the conformation-related interactions might depend on both the receptor subtype and antidepressant molecular structure. Along the same evidence, we observed that imipramine is dissociated from the desensitized hα4β2 AChR at a slightly slower rate than that from the resting AChR (Table 3), indicating a slightly stronger interaction with the desensitized hα4β2 AChR. Since these experiments were performed in the presence of κ-BTx or (±)-epibatidine, we discard the possibility that imipramine is interacting with the agonist/competitive antagonist binding sites. A potential explanation is that the hα4β2 AChR conformational changes induced by the agonist are so subtle that only the kinetics approach can detect them. In order to clarify this issue, we are planning to determine the kinetics of TCA-induced hα4β2 AChR inhibition using single-channel current detection as previously determined in the case of other AChRs (Gumilar et al., 2003; Gumilar and Bouzat, 2008).

Proposed mechanisms of binding for imipramine and both mecamylamine enantiomers were additionally studied by docking simulations in the hα4β2 AChR ion channel model. The analysis of the obtained hα4β2 AChR-imipramine molecular complexes indicates that imipramine in either the neutral or protonated form binds exclusively to the middle portion of the M2 transmembrane segments between the leucine (position 9′) and valine rings (position 13′) (see Fig. 8A). The same basic result was obtained for the hα3β4 AChR (Arias et al., 2010a). The van der Waals and hydrogen bond interactions are in agreement with the thermodynamic results where a combination of enthalpic and entropic components was observed in the desensitized and resting AChR ion channels (see Table 4). Moreover, TCAs may induce more local conformational changes or solvent reorganization in the binding pocket of the desensitized AChR ion channel compared to that in the resting AChR ion channel.

Previous photoaffinity labeling, radioligand competition binding, and molecular docking studies on Torpedo AChRs indicate that the TCA binding site overlaps the PCP locus which is probably located between the threonine (position 2′) and leucine (position 9′) rings (Pratt et al., 2000; Sanghvi et al., 2008; Hamouda et al., 2008; Eaton et al., 2000; reviewed in Arias et al., 2006a). Our docking results in the hα4β2 AChR ion channel indicate that imipramine, in either the neutral or protonated state, interacts with a domain formed between the leucine (position 9′) and valine (position 13′) rings (Fig. 8A). On the other hand, the binding site location for mecamylamine in the hα4β2 AChR ion channel depends on the ionization state. Docking simulations of protonated S(+)-mecamylamine (Fig. 8C) and R(−)-mecamylamine (in the protonated and neutral forms; data not shown) suggest that they interact with the extracellular edge of the ion channel by forming an ion-pair contact with the acidic residue α4-Glu261 at the outer ring (position 20′). Neutral S(+)-mecamylamine, in turn, forms a complex in the middle portion of the channel between the leucine and valine rings (Fig. 8B). The differential mode of interaction between imipramine and mecamylamine helps to explain the observed lack of [3H]imipramine displacement by (±)-mecamylamine in either AChR conformational state (Fig. 5 and Table 2). Since mecamylamine is a relatively strong base (pKa = 11.4; Nangia et al., 1996) it exists mainly in the protonated state at physiological pH and thus, the protonated mode of interaction (see Fig. 8C) should dominate in the hα4β2 ion channel. This is supported by the voltage dependence of mecamylamine inhibiting the α4β2 AChR (Papke et al., 2001). Considering that (±)-mecamylamine efficiently inhibits the hα4γ2 AChR (Table 1), we can hypothesize that there is a binding site for mecamylamine in the hα4β2 AChR ion channel located in a different domain from that for TCAs (as illustrated in Fig. 8D). Thus, since imipramine binding occurs significantly deeper in the ion channel than that observed for mecamylamine, both ligands do not interfere their mutual binding to finally inhibit the ion channel. The same basic result was obtained for the hα3β4 AChR (Arias et al., 2010a).

Collectively, our data indicate that TCAs and (±)-mecamylamine functionally block agonist-induced hα4β2 AChR ion flux, and TCAs, but not (±)-mecamylamine, bind with significant affinity to the [3H]imipramine locus in the hα4β2 AChR ion channel. Molecular modeling results show that TCAs interact with a channel domain formed between the leucine and valine rings, whereas mecamylamine predominantly acts at the outer ring, supporting the view that TCAs and mecamylamine do not interfere with each other. In addition, mecamylamine can be first attracted to the extracellular channel mouth by electrostatic interactions before binding to a luminal locus in its neutral state. Functionally, both NCAs may efficiently inhibit the AChR by a combination of different mechanisms including ion channel blocking, and in the case of imipramine, by decreasing its dissociation from the desensitized state.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Science Foundation Arizona and Stardust Foundation and the College of Pharmacy, Midwestern University (to H.R.A.), and by grants from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (N° NN 405297036) and FOCUS and TEAM research subsidy from the Foundation for Polish Science (to K.J.). This research was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging. The authors thank to Paula Iacoban for her technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- AChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- NCA

noncompetitive antagonist

- TCAs

tricyclic antidepressants

- κ-BTx

κ-bungarotoxin

- RT

room temperature

- BS buffer

binding saline buffer

- Ki

inhibition constant

- Kd

dissociation constant

- Ka

association constant

- koff

dissociation rate constant

- kon

association rate constant

- IC50

ligand concentration that produces 50% inhibition (of binding or of agonist activation)

- nH

Hill coefficient

- EC50

agonist concentration that produces 50% AChR activation

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FLIPR

fluorescent imaging plate reader

References

- Arias HR. Thermodynamics of nicotinic receptor interactions. In: Raffa RB, editor. Drug–receptor thermodynamics: introduction and applications. USA: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2001. pp. 293–358. [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR. Ligand-gated ion channel receptor superfamilies. In: Arias HR, editor. Biological and biophysical aspects of ligand-gated ion channel receptor superfamilies. chapter 1 Kerala, India: Research Signpost; 2006. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR, Bhumireddy P, Bouzat C. Molecular mechanisms and binding site locations for noncompetitive antagonists of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006a;38:1254–76. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR, Bhumireddy P, Spitzmaul G, Trudell JR, Bouzat C. Molecular mechanisms and binding site location for the noncompetitive antagonist crystal violet on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochemistry. 2006b;45:2014–26. doi: 10.1021/bi051752e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR, Gumilar F, Rosenberg A, Targowska-Duda KM, Feuerbach D, Jozwiak K, et al. Interaction of bupropion with muscle-type nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in different conformational states. Biochemistry. 2009;48:4506–18. doi: 10.1021/bi802206k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR, Targowska-Duda KM, Sullivan CJ, Feuerbach D, Maciejewski R, Jozwiak K. Different interaction between tricyclic antidepressants and mecamylamine with the human α3β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Int Neurochem. 2010a;56:642–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR, Feuerbach D, Bhumireddy P, Ortells MO. Inhibitory mechanisms and binding site locations for serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010b;42:712–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR, Trudell JR, Bayer EZ, Hester B, McCardy EA, Blanton MP. Noncompetitive antagonist binding sites in the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ion channel. Structure–activity relationship studies using adamantane derivatives. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7358–70. doi: 10.1021/bi034052n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arita M, Wada A, Takara H, Izumi F. Inhibition of 22Na influx by tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants and binding of [3H]imipramine in bovine adrenal medullary cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;243:342–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldessarini RJ. Drugs and the treatment of psychiatric disorders. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, editors. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 10. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 447–83. [Google Scholar]

- Caldarone BJ, Hrrist A, Cleary MA, Beech RD, King SL, Picciotto MR. High-affinity nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are required for antidepressant effects of amitriptyline on behavior and hippocampal cell proliferation. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:657–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (Ki) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 percent inhibition (IC50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton MJ, Labarca C, Eterović VA. M2 Mutations of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor increase the potency of the non-competitive inhibitor phencyclidine. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:44–51. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000701)61:1<44::AID-JNR5>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisensamer B, Rammes G, Gimpl G, Shapa M, Ferrari U, Hapfelmeier G, et al. Antidepressants are functional antagonists at the serotonin type 3 (5-HT3) receptor. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:994–1007. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch RW, Xiao Y, Kellar KJ, Daly JW. Membrane potential fluorescence: a rapid and highly sensitive assay for nicotinic receptor channel function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4909–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630641100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotzbach RK, Preskorn SH. Brain concentrations of tricyclic antidepressants: single-dose kinetics and relationship to plasma concentrations in chronically dosed rats. Psychopharmacology. 1982;78:25–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00470582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumilar F, Arias HR, Spitzmaul G, Bouzat C. Molecular mechanism of inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by tricyclic antidepressants. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:964–76. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumilar F, Bouzat C. Tricyclic antidepressants inhibit homomeric Cys-loop receptors by acting at different conformational states. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;584:30–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda AK, Chiara DC, Blanton MP, Cohen JB. Probing the structure of the affinity-purified and lipid-reconstituted Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12787–94. doi: 10.1021/bi801476j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg RC, Raggenbass M, Bertrand D. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to brain function. Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;147:1–46. doi: 10.1007/s10254-003-0005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaguirre V, Fernández-Fernández JM, Ceña V, González-García C. Tricyclic antidepressants block cholinergic nicotinic receptors and ATP secretion in bovine chromaffin cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;418:39–42. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jozwiak K, Haginaka J, Moaddel R, Wainer IW. Displacement and nonlinear chromatographic techniques in the investigation of interaction of noncompetitive inhibitors with an immobilized α3β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor liquid chromatographic stationary phase. Anal Chem. 2002;74:4618–24. doi: 10.1021/ac0202029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jozwiak K, Hernandez S, Kellar KJ, Wainer IW. The enantioselective interactions of dextromethorphan and levomethorphan with the α3β4-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: comparison of chromatographic and functional data. J Chromatogr B. 2003;797:373–9. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(03)00608-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jozwiak K, Ravichandran S, Collins JS, Wainer IW. Interaction of noncompetitive inhibitors with an immobilized α3β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor investigated by affinity chromatography, quantitative-structure activity relationship analysis, and molecular docking. J Med Chem. 2004;47:4008–21. doi: 10.1021/jm0400707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López MG, Montiel C, Herrero CJ, García-Palomero E, Mayorgas I, Hernández-Guijo JM, et al. Unmasking the functions of the chromaffin cell α7 nicotinic receptor by using short pulses of acetylcholine and selective blockers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14184–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelmore S, Croskery K, Nozulak J, Hoyer D, Longato R, Weber A, et al. Study of the calcium dynamics of the human α4β2, α3β4 and α1β1γδ nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2002;366:235–45. doi: 10.1007/s00210-002-0589-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa A, Fujiyoshi Y, Unwin N. Structure and gating mechanism of the acetylcholine receptor pore. Nature. 2003;423:949–55. doi: 10.1038/nature01748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moaddel R, Jozwiak K, Wainer IW. Allosteric modifiers of neuronal nicotinic receptors: new methods, new opportunities. Med Res Rev. 2007;27:723–53. doi: 10.1002/med.20091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moaddel R, Jozwiak K, Whittington K, Wainer IW. Conformational mobility of immobilized α3β2, α3β4, α4β2, α4β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Anal Chem. 2005;77:895–901. doi: 10.1021/ac048826x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moaddel R, Wainer IW. The preparation and development of cellular membrane affinity chromatography columns. Nat Protocol. 2009;4:197–205. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MA, McCarthy MP. Snake venom toxins, unlike smaller antagonists, appear to stabilize a resting state conformation of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1235:336–42. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)80022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nangia A, Andersen PH, Berner B, Maibach HI. High dissociation constants (pKa) of basic permeants are associated with in vivo skin irritation in man. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;34:237–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Sanberg PR, Shytle RD. Analysis of mecamylamine stereoisomers on human nicotinic receptor subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297:646–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Brunzell DH, Caldarone BJ. Effect of nicotine and nicotinic receptors on anxiety and depression. Neuroreport. 2002;13:1097–106. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200207020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popik P, Kozela E, Krawczyk M. Nicotine and nicotinic receptor antagonists potentiate the antidepressant-like effects of imipramine and citalopram. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139:1196–202. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt MB, Pedersen SE, Cohen JB. Identification of the sites of incorporation of [3H]ethidium diazide within the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ion channel. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11452–62. doi: 10.1021/bi0011680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana B, McMorn SO, Reeve HL, Wyatt CN, Vaughan PF, Peers C. Inhibition of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by imipramine and desipramine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;250:247–51. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90388-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabey K, Paradiso K, Zhang J, Steinbach JH. Ligand binding and activation of rat nicotinic α4β2 receptors stably expressed in HEK293 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55:58–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghvi M, Hamouda AK, Jozwiak K, Blanton MP, Trudell JR, Arias HR. Identifying the binding site(s) for antidepressants on the Torpedo nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: [3H]2-azidoimipramine photolabeling and molecular dynamics studies. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:2690–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield GG, Witko B, Warnik JE, Albuquerque EX. Differentiation of the open and closed states of the ionic channels of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by tricyclic antidepressants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:5240–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.5240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scatchard G. The attraction of proteins for small molecules and ions. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1949;51:660–72. [Google Scholar]

- Shytle RD, Silver AA, Lukas RJ, Newman MB, Sheehan DV, Sanberg PR. Nicotinic receptors as targets for antidepressants. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:525–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin N. Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:967–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade JL, Bergold AF, Carr PW. Theoretical description of nonlinear chromatography, with applications to physicochemical measurements in affinity chromatography and implications for preparative-scale separations. Anal Chem. 1987;59:1286–95. [Google Scholar]