Abstract

Introduction

Proteins are effective biotherapetics with applications in diverse ailments. Despite being specific and potent, their full clinical potential has not yet been realized. This can be attributed to short half-lives, complex structures, poor in vivo stability, low permeability frequent parenteral administrations and poor adherence to treatment in chronic diseases. A sustained release system, providing controlled release of proteins, may overcome many of these limitations.

Areas covered

This review focuses on recent development in approaches, especially polymer-based formulations, which can provide therapeutic levels of proteins over extended periods. Advances in particulate, gel based formulations and novel approaches for extended protein delivery are discussed. Emphasis is placed on dosage form, method of preparation, mechanism of release and stability of biotherapeutics.

Expert opinion

Substantial advancements have been made in the field of extended protein delivery via various polymer-based formulations over last decade despite the unique delivery-related challenges posed by protein biologics. A number of injectable sustained-release formulations have reached market. However, therapeutic application of proteins is still hampered by delivery related issues. A large number of protein molecules are under clinical trials and hence there is an urgent need to develop new methods to deliver these highly potent biologics.

Keywords: Protein delivery, sustained release, formulation, stability, release mechanism, implant, hydrogel, nanoparticle, microparticle and thermosensitive gel

1. Introduction

Proteins are large biomolecules with complex tertiary (3°) and quaternary (4°) structures. These macromolecules participate in a number of biological pathways and have diverse functionalities such as enzymes, hormones, interferons and antibodies. The complex 3° and 4° structures impart important properties including selectivity, specificity and high potency. Abundance in various biological functions, specificity and potency are most important parameters. Newer targets are being discovered at a rapid rate due to advanced understanding of pathology such as cancer and autoimmune diseases. Precise number of proteins expressed in the human body is not known yet. But various reports suggest that there are at least 84,000 to 200,000 different proteins in the human body1, 2. Protein-protein interaction plays a key role in most biological pathways. It may be targeted by designing agonist or antagonist peptides and proteins3, 4. Advancement in high throughput (HTS) technology such as hot-spot determination has also catalyzed development of novel biotherapeutics3, 5. Therapeutic protein development and production have reached advanced stages owing to innovations in manufacturing technology6, process control 7, and protein characterization8, 9. Additionally, protein biotherapeutics have shown to be very efficacious and specific, such as antibodies. However, we are yet to take full advantage of these potent biotherapeutics despite the fast-paced advancements in protein therapeutics R&D and production. U.S. biopharmaceutical industry is one of most innovative and research intensive enterprise as noted by Congressional Budget Office10. As per recent market survey pharmaceutical/biotech industry invested nearly a $50 billion every year from 2011 to 2013 in R&D of new medicines and most of it was spent for biopharmaceutical R&D11. As a result, there are more than 907 biotherapeutics in various phases of clinical trials. Of these biotherapeutics, majority are protein biotherapeutics including 338 monoclonal antibodies, 93 recombinant proteins, 20 interferons and 250 vaccines for various conditions such as cancer, autoimmune diseases and infectious diseases1. A detailed representation of the protein biotherapeutics currently in clinical trial is depicted in reference#1.

Proteins pose a number of delivery related challenges due to a myriad of factors. Some of them are large size, hydrophilicity, poor permeability across biological membranes (such as GI tract), susceptibility to enzymatic degradation, complex structure and immunogenicity12. Large molecular size and hydrophilicity hinder permeation of proteins across biological barriers such as GI mucosa leading to poor absorption following oral administration. Extreme gastric pH and digestive enzymes degrade proteins prior to oral absorption. Following GI absorption, the first pass metabolism eliminates a significant fraction of absorbed biomolecules. Hence, protein delivery via most favored - oral route - is highly challenging. Hence, a large portion of approved and investigational protein molecules is administered via parenteral routes (IV, IM or SC). Proteins also suffer from a number of physical, chemical and biological instability due to their complex secondary, tertiary and quaternary structures. Any alteration in “active” confirmation may lead to loss of activity and irreversible aggregation of proteins. Vulnerability towards enzymatic degradation under in vivo condition results into short half-lives even with parenteral administration. Many protein therapeutics are intended for chronic ailments such as bevacizumab for age-related macular degeneration. Short half-lives of proteins require frequent parenteral administrations to maintain therapeutic levels. However, frequent parenteral administrations are not patient compliant. In addition, frequent administrations may not be well tolerated. For example, frequent intravitreal injections have been shown to be associated with many complications including cataract, retinal hemorrhage and detachment13.

Invasive and non-invasive routes have been investigated with various formulations to deliver proteins. As mentioned earlier, most frequently used invasive routes are IV, IM and SC. Non-invasive routes include oral, rectal, transdermal and inhalation. Of these, the most preferred noninvasive route is per-oral administration, which is also the “Holy Grail” of protein delivery. It is highly challenging among the noninvasive routes due to the limitations discussed earlier. Major approaches used for oral protein delivery include use of absorption enhancers such as surfactants, enzyme inhibitors, polymer–inhibitor conjugates, mucoadhesive particles, thiolated polymers, nanoparticles, microparticles and emulsion based formulations14-17. Nevertheless, all these approaches suffer from certain drawbacks and side effects. For example, cost of effective enzyme inhibitors, adverse effects due to frequent oral administrations in chronic diseases, poor stability of formulations such as liposomes in GI track, poor loading efficiency of protein in particles owing to hydrophililicity, polydispersed size distribution and particle aggregation 17. Similar limitations are also associated with non-invasive routes of delivery18, 19. Moreover, it is challenging to achieve controlled protein delivery for extended duration via ‘patient compliant’ non-invasive routes. A potential reason for the failure of treatment strategy in chronic diseases may be lack of adherence to a given treatment regimen by patient. Therefore, frequent administration is not a recommended strategy for chronic ailments. As per an estimate by WHO, only 50% of patients suffering from chronic diseases stick to the treatment regime in developed countries20. In developing countries, adherence to prolonged therapy is even lower 20. Therefore, proteins are suitable candidate for sustained release formulations. Advantages of sustained protein delivery formulation include better adherence to chronic therapy, in vivo stability, local delivery, fewer side effects, reduction in dose and dosing frequency, and improved patient compliance. Furthermore, parenteral routes, although not very patient compliant, may be a simpler answer to limitations and drawbacks associated with non-invasive administrations. Extended duration of protein delivery with lower frequency of administration may improve patient compliance significantly.

Ideal protein delivery formulation should be able to provide controlled release to maintain therapeutic levels for an extended duration and ensure stability of encapsulated protein. Components of delivery system must be biodegradable and/or biocompatible, non-immunogenic, non-toxic and preferably FDA approved for human use. If the formulation is intended via parenteral route, it should be possible to inject it through a narrow gauge needle to minimize pain. In addition, in a few cases, it is impractical to use higher gauge needles. For example, in case of intravitreal injections, a 27G to 30G needle is recommended to avoid damage to intraocular tissues. Volume of injection should also be considered carefully depending on the route of administration. Protein structure and activity should not be altered during the preparation of delivery system and protein must be in active conformation following in vivo release. In particulate and hydrogel based systems, initial burst release is a serious concern. In the case of particle-based systems, burst release is due to high surface adsorption of protein. Higher initial burst release of proteins may shorten total duration of release and result in dose-dependent adverse effects. Therefore, the formulation must be optimized to achieve minimal burst release. Above all these factors, method of formulation preparation should be scalable, robust and reproducible. Statistical methods such as quality-by-design, design of experiments21 and in-process quality control methods such as six-sigma may be able to aid development of high quality product with robust and reproducible method of manufacturing7, 22.

Despite all these challenges, substantial advancements have been made in the field of extended protein delivery via various polymer-based formulations over last decade. A number of injectable sustained-release formulations have reached market. Nonetheless, there is room for further development. In present review, recent advancements in particulate and gel based formulations and other novel approaches for controlled extended protein delivery are discussed. Emphasis is placed on dosage form, method of preparation, mechanism of release and stability of biotherapeutics.

2. In situ Injectable Gel/Implants

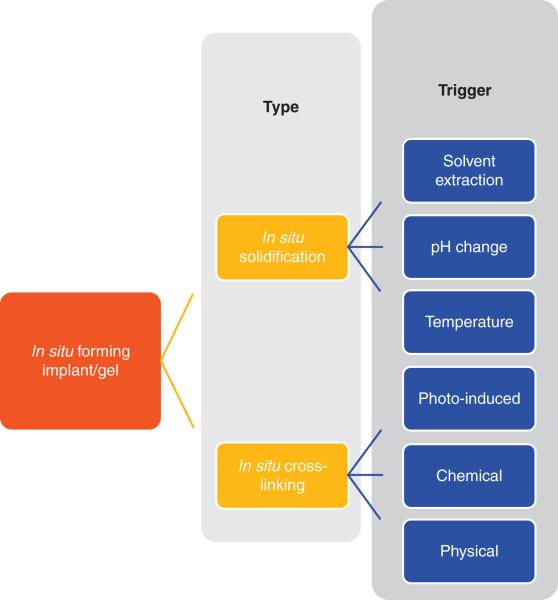

Injectable implants have been designed to deliver a variety of therapeutics, including small molecules and proteins for extended duration23, 24. One of the reasons for wide spread use of these systems is the simplicity. The system is liquid or injectable semi-solids, which turn to gel/implant upon injection. A number of mechanisms govern the process of implant/gel formation. Broadly, these formulations can be classified as in situ phase inversion and crosslinking systems based on mechanism of implant/gel formation. Classification of in situ forming implant/gel systems is represented in figure 1. In situ implant formation via solvent extraction has been thoroughly investigated and is successful with two marketed formulations. Temperature dependent sol-to-gel systems have a number of advantages over the previously developed systems. Several pH and temperature dependent hybrid polymers have also been developed to provide better control over the process of implant formation. Temperature, phase inversion and pH change are most investigated triggers to form in situ gel and are discussed.

Figure 1.

Classification of in situ forming implant/gel systems based of mechanism of formation.

2.1. Solvent extraction/Phase inversion systems

Injectable implant consists of polymer solution in suitable water-miscible organic solvent, where in protein is suspended in organic solvent. Drug-loaded implant is formed upon in vivo injection. Following administration, water miscible organic solvent diffuses out in the aqueous environment of surrounding tissue, resulting in precipitation of water insoluble polymer. During precipitation, protein is entrapped inside the polymer matrix. Typical polymers used for these systems include polyesters such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), poly(lactic acid) (PLA), Poly(glycolic acid) (PGA) and polycaprolactone (PCL). A number of solvents with varying polarity have been examined including N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP), DMSO, ethanol, ethyl benzoate, triacetin, ethyl acetate, benzyl benzoate, PEG500-dimethylether and glycofurol for dissolving polymers. NMP and DMSO are widely employed despite the associated toxicities. Recently, PEG-alkyl ether and glycofurol have been investigated for PLGA implants. Both solvents have been indicated to be well tolerated and biocompatible in vivo25-27. Glycofurol has been shown to be compatible with PLGA polymer causing minimal polymer degradation. The objective of the system is to deliver proteins over a long period to lower dosing frequency and provide stability to protein. The rate and duration of release for phase inversion systems/implants are influenced by variables such as gelling rate, porosity of implant and burst release. These factors are again dependent on the polymer type, concentration and molecular weight, solvent system, polymer crystallinity and additives28-32.

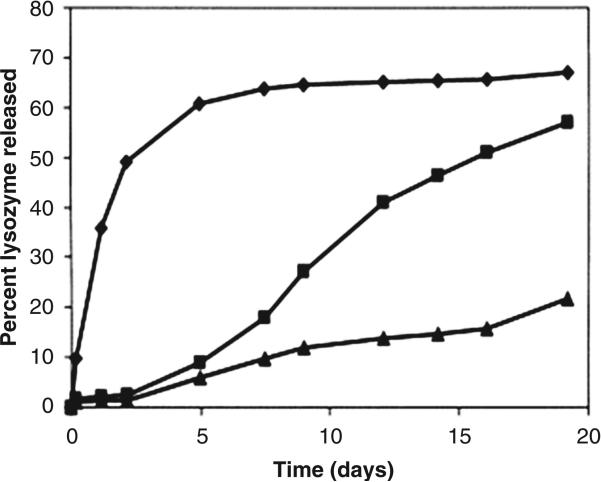

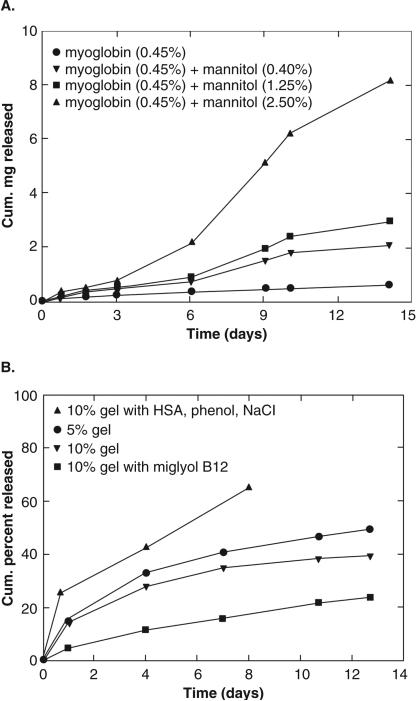

One of the widely used solvents for injectable implants is NMP. The rate of phase inversion leading to implant formation is very rapid due to its relatively high polarity compared to solvents such as ethyl benzoate and benzyl benzoate. Shortcoming of rapid phase inversion is formation of porous implants with highly evolved network of interconnected pores. Porous implants result in a significant burst release of peptides and proteins. For example, 40% of lysozyme was released from a PLGA implant prepared in NMP, followed by very slow release of remaining dose29. Conversely, less polar solvents such as triacetin and ethyl benzoate produce implants with less porosity resulting in significantly reduced burst effects (<5-10% of initial dose) [Figure 2]29. Depending on solubility of protein or peptide, it may be dispersed or solubilized in the polymer solution during preparation. It has been shown that when proteins are in dispersed state, the release rate is higher33. When dispersed protein is released from the implant, the porosity of the implant is increased tremendously resulting in higher release rate. Similarly, type of additive also influences the release rate and burst release. Addition of a water soluble additive results in high release rate, even from an implant formed using triacetin [Figure 3a]33. Release rate was found to be directly proportional to concentration of mannitol. The effect was very prominent during late phase. Again, it was due to formation of porous network upon dissolution of mannitol during release, similar to a system where protein is dispersed in implant. In contrast, addition of hydrophobic additive such as linoleic triglyceride (Miglyol® 818) resulted in a much slower release rates [Figure 3b]33. Similar results are reported in an in vivo, where PLGA implants containing hGH were prepared using NMP, triacetin, ethyl benzoate and benzyl benzoate34. Depot formed by benzyl benzoate resulted in sustained levels of hGH levels in the plasma within a therapeutic window 34. In order to further lower the burst effect and control overall release profile, physical properties of the hGH were also manipulated. hGH was modified by preparing complex with Zn and densification of protein. A substantial control over release profile and negligible burst effect was observed with Zn-complexed and densified hGH compared to lyophilized and densified hGH34. A reduction in the initial burst was attributed to reduced aqueous solubility following complex formation and densification of hGH protein. The influence of polymer molecular weight, drug loading and polymer concentration on efficacy of leuprolide from PLGA implants prepared in NMP35. Neither drug loading (3-6%) nor polymer concentration (40-50%) had any influence on efficacy of leuprolide implant in rat model. However, as expected, low molecular weight PLGA had shorter duration of action compared to high molecular weight polymer. In canine model, one of the formulation resulted in suppression of testosterone levels over 3 months following single injection 35. In an attempt to lower burst effect from PLGA implants, surfactants (triton X and PVA) have also been incorporated in implants36. Addition of surfactants influenced mechanical stability of PLGA, which in turn reduced extent of burst release.

Figure 2.

Lysozyme release rate from 50 wt% PLGA/solvent solutions; NMP (◆); triacetin (■); ethyl benzoate (▲) quenched into a PBS solution. Reproduced with permission from [29].

Figure 3.

(a) Effect of mannitol on release of myoglobin from PLGA formulations. (b) Effect of polymer concentration and additives on myoglobin release from PLGA formulations. Reproduced with permission from [33].

In order to further control the release profile and improve peptide loading in implants a few modified techniques have been investigated. One such alternative injectable implant system is referred to as SABER™ developed by Durect Corporation. Instead of polyesters such as PLGA or PLA, SABER™ employs Sucrose Acetate Isobutyrate (SAIB) to form matrix. SAIB is dissolved in organic solvent such as ethanol or benzyl benzoate and injected to form a depot with slower phase inversion. Okuma et al utilized the SABER system to delivery hGH with a few modification37. PLA (1.0% & 10% w/w) was added along with SAIB in ethanol or benzyl benzoate and lyophilized hGH was suspended in organic solvent. Higher drug loading (10%) along with injectability through a narrow gauge needle (25G) were advantages of the system. During in vitro release from SABER system without PLA, a huge burst release (at 24 h) of 78% of total dose was observed. Interestingly, when SABER system was modified by adding 1% and 10% of PLA, burst release of only 2% and 0.2% hGH was released, respectively. However, a significant amount of protein was degraded during release due to presence of organic solvent exposing proteins to organic-aqueous interface. In order to minimize protein denaturation in SABER system, Pechenov et al investigated encapsulation of proteins in crystal form38. α-amylase was used as a model protein and suspended in SAIB with ethanol (SAIB/ethanol) or PLGA solution in acetonitrile (PLGA/acetonitrile) system, in crystal or amorphous states. A very high protein loading (>30%) was obtained when protein was used in crystal state in both systems. Long-term storage stability at 4°C suggested that protein in crystal form was more stable in SAIB/ethanol and PLGA/acetonitrile systems with nearly 100% activity of protein. A negligible amount of initial burst was observed during in vitro release from PLGA/acetonitrile system having crystalline amylase. Crystal shape also influenced the release profile. Rod-shaped crystals had a significant high burst compared to absence of burst effect with grain-shaped crystals.

As a variation to injectable forming implant system, an injectable in situ forming microparticle system has been developed39-41. In situ microparticle (ISM) forming system consists of an o/w or o/o emulsion prepared by dissolving polymer, typically PLGA, in organic solvent such as NMP or triacetin. Following injection, microparticles are formed in situ via solvent extraction. The emulsion system typically has less viscosity compared to plain oil-based system, hence can be injected through a narrow gauge needle. Influence of various process parameters on performance of injectable ISM (o/o PLGA emulsion system) has been investigated using cytochrome c (Mw: 12,327 Da) and myoglobin (Mw: 16,950)41. PLGA (RESOMER grade RG 502 H) was dissolved in triacetin along with drug in PEG 400, where migloyl 812 was continuous phase. The dispersion was stabilized by addition of Tween 80 and Span 80. Upon injection, dispersion forms solid matrix-type microparticles entrapping the drug (in situ formed microspheres)42. Similar to PLGA injectable implants, release rate was dependent on porosity of microspheres, molecular weight of PLGA and encapsulation efficiency. A burst release of 30-40% was observed for cytochrome-c with ISMs. An increase in burst release was observed for myoglobin release upon addition of mannitol. Presence of mannitol (5.4%) in ISMs significantly enhanced burst release from 30% to 70%. The encapsulated myoglobin was extracted from ISM. The structure of extracted myoglobin was found to be intact. However, with all modifications in ISMs system, the maximum length of release was only 2 week. Influence formulation parameters such as molecular weight of PLGA and PLA, polymer blending and polymer concentration on in situ microsphere formation and leuprolide release rate and duration has also been investigated39. Low molecular weight PLGA resulted in lower initial burst compared to high molecular weight. It was attributed to slower rate of solvent extraction (NMP) in external aqueous media, which resulted in less porous dense microspheres. Furthermore, PLGA with free acid end groups resulted in slower rate of release compared to end esterified PLGA, presumably due to electrostatic interactions between polymer and leuprolide. High leuprolide loading of 15% was obtained in an ISM system containing a polymer blend (PLA R 203H and R 202H at ratio of 1:1, polymer concentration 30%). It released leuprolide over 6 months (in vitro) with minimal burst release.

Despite the advancements in achieving extended release and near success in a few cases, application of injectable implants is mostly limited to the peptides. It is presumably due to fragile 3° and 4° structures of proteins that are susceptible to degradation following exposure to organic solvents and oil-aqueous interface. Widely explored solvent NMP has been shown to cause significant aggregation of protein as discussed earlier. Although injectable PLGA depot system (Eligard Injection Kit® containing leuprorelin acetate in NMP) has reached market, cases of systemic allergic dermatitis due to NMP has been reported43. To achieve extended duration of release, a formulation must have higher drug loading. With most of the systems investigated so far, drug loading ranged from ~3-12%. Nevertheless, use of polymeric blend systems (ISMs) and crystalline protein may provide better drug loading.

2.2.Thermosensitive gels

Thermosensitive systems are composed of aqueous polymer solution at room temperature. The solution undergoes sol-to-gel transition to form a solid gel structure when injected due to change in temperature. Typical thermosensitive polymers are amphiphilic block co-polymers, where the hydrophobic segment consists of PLGA, PLA, PCL or PPO. PEG is widely explored as hydrophilic block due to its excellent water solubility and biocompatibility. Protein can be dissolved in aqueous solution along with polymer, which is encapsulated upon formation of gel. The characteristics of gel depend on the concentration of polymer, molecular weight and type of polymer forming hydrophobic block. An advantage with thermosensitive gel system over injectable implant is absence of organic solvent, which is responsible for protein degradation and in vivo toxicity. Hence, thermosensitive gel system is more compatible with tissue and therapeutic protein. In addition, aqueous solution based formulation can be easily filter sterilized and injected easily via narrow gauge needles.

Thermosensitive gel system composed of PLGA-PEG-PLGA polymer is one of the widely investigated system and commercially available under ReGel®. ReGel® forms clear aqueous solution at room temperature at ~23% w/w that turns to gel at body temperature following injection. Ssol-to-gel transition in ReGel® is reversible; hence, the gel turns back to liquid upon decrease in temperature. ReGel® has been investigated extensively to deliver peptide and proteins including lysozyme, porcine growth hormone (pGH), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, insulin and recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen44-47.

Influence molecular weight of PLGA and PEG segments on sol-to-gel transition and release characteristics of proteins is well documented47. Two ReGel® polymers with PEG Mw 1000 Da (ReGel®-1) and 1450 Da (ReGel®-2) were synthesized with a total molecular weight of 4200. It was shown that the ReGel® with PEG 1000 Da had lower critical gelling temperature compared to PEG 1450 Da at all concentrations. Sol-to-gel transition was also reversible. In vitro release studies were performed with Zn-insulin, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and pGH from ReGel® 1 & 2 at 23% w/w. In all the cases, total release duration was 2-3 weeks with a burst release of 25-40%, except for Zn-insulin from ReGel®-2. A drastically slow release rate with negligible burst of less than 10% was observed for Zn-insulin from ReGel®-2 compared to ReGel®-1. No explanation was provided for this phenomenon. It was also shown that complexation of insulin and pGH with Zn resulted in low initial burst. In an in vivo hypophysectomized rat model, single injections of ReGel®-1/pGH or ReGel®-1/Zn-pGH (Dose: 1 ml of solution containing 70 mg/ml pGH) was nearly as efficacious as daily injections of 5 mg of pGH for 14 days.

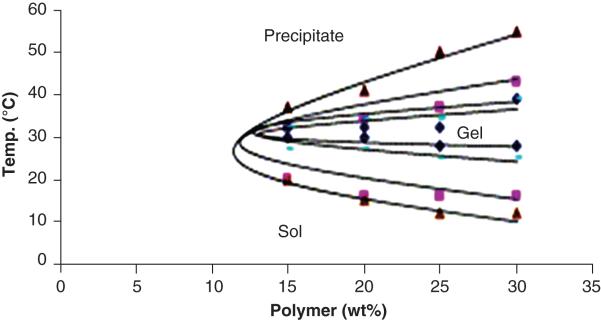

Influence of polymer compositions and concentrations on release characteristics has also been investigated using a model protein lysozyme 48. Thermosensitive triblock copolymers (PLGA–PEG–PLGA) with different block lengths of PLGA (PEG Mw 1000Da) were synthesized. It was observed that the sol-to-gel and gel-to-sol transitions were dependent on the molecular weight of each block and concentration. Lower critical gelling temperature rises and upper critical gelling temperature was falls with increase in molecular weight [Figure 4]48. Moreover, the process of sol-to-gel transition is not reversible for higher molecular weight polymers. In vitro release studies were performed using lysozyme as a model protein at 30% w/v polymer concentration. With increase in polymer molecular weight, the initial burst effect was also reduced from 41.2±5.4% (Mw 1602 Da) to 16.1±3.9% (Mw 7859 Da). Following initial burst, all the block co-polymers exhibited slow release of lysozyme over period of 4 weeks. Similarly, initial burst effect was also shown to be inversely proportional to the polymer concentration. Triblock copolymer PLGA-PEG-PLGA (MW 1400-1000-1400) was also utilized to deliver pGH49. In vitro release at 0.12% and 0.42% w/v pGH exhibited nearly zero-ordered release at 30% w/v polymer concentration suggesting that diffusion was major mechanism of release along with some influence of polymer degradation. At higher pGH concentration, the release reached plateau phase after 4-week suggesting incomplete release. However, nearly 100% was released from gel containing 0.12% w/v pGH. Similar results were observed in rabbit model following S.C. injections at 0.12% and 0.42% w/v doses. Bioavailability at low dose formulation was 86%, in contrast to 38% at higher dose. Poor bioavailability at 0.42% could be due to incomplete release of pGH from thermosensitive gel. Incomplete release was attributed to protein aggregation, which occurs at higher proteins concentration in aqueous solution50-52. Recently, it has been shown that protein aggregation can be minimized in PLGA implants using sugars such trehalose and histidine-HCl buffer using bovine serum albumin (BSA) and model protein53.

Figure 4.

The phase diagram of PLGA–PEG–PLGA triblock copolymer. Key: (◆) PLGA995– PEG1000–PLGA995, (▬) PLGA1125–PEG1000–PLGA1125, (■) PLGA1350–PEG1000–PLGA1350, and (▲) PLGA1400–PEG1000–PLGA1400. Reproduced with permission from [48].

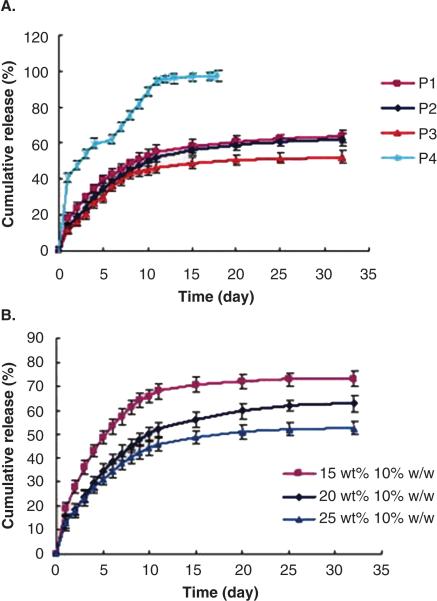

Another class of thermosensitive triblock polymers is based on polycaprolactone rather than lactide or glycolide based PLGA, PLA or PGA. One advantage in utilizing caprolactone-based polymer is absence of acidic byproducts such as lactic acid and glycolic acid, which are formed following degradation of PLGA. These byproducts turn mirco-environment acidic, which may be deleterious to proteins resulting in loss of activity54, 55. Hence, proteins released from PCL based implants have shown better stability comparatively56, 57. Guilei Ma et al, synthesized a series of PCL-PEG-PCL gelling polymers with average molecular weights ranging from 2600 to 4100 Da58. All the polymers exhibited temperature dependent sol-to-gel transition. These hydrogels were capable of sustaining the release of model proteins, BSA and horseradish peroxidase (HRP), for more than a month under in vitro conditions. Taking the advantage of aqueous solution based system; it was possible to prepare formulation with high protein loading (10% w/w). The rate and total duration of release were dependent on the polymer molecular weight and concentration. The release rate was slower for hydrogels with high molecular weight with less than 20% of total burst release. Similarly, release rate was lowered considerably upon increasing the polymer concentration from 15 to 25 wt%. Duration of release was more than a month with high molecular weight polymer [Figure 5]58. However, it is also worth noting that, in all systems with high molecular weight gels, 40-60% of BSA was released within first 15 days followed by an incomplete release in vitro. Only hydrogels from low molecular weight polymer (Mw 2600 Da) exhibited complete release within 20 days. In vivo gel formation and degradation of PCL-PEG-PCL copolymers indicated that the hydrogel lasted for more than 45 days in mice following subcutaneous injection. Gong CY et al, synthesized a series of triblock copolymers with different block arrangement (PEG-PCL-PEG) having molecular weights 2992 Da to 5046 Da59 and performed in vitro release with BSA as a model protein. The authors investigated influence of total protein loading on release. Hydrogel with higher protein loading resulted in lower initial burst and slower release rate. Total duration of release was 2 week. However, no formulation exhibited complete release of BSA. Formulation with less loading showed only 65% of release. Stability of released BSA was examined by SDS-PAGE analysis. However, no data on stability of BSA in the formulation after 2 weeks of release was shown. PEG-PCL-PEG thermosensitive polymer was utilized to deliver basic fibroblastic growth factor (bFGF). bFGF-loaded hydrogel maintained strong humoral immune response for more than 12 weeks in BALB/c mice. Release rate and initial burst were influenced by initial protein loading as shown earlier for BSA-loaded hydrogels. PCL based thermosensitive polymers provide advantage over lactide and glycolide based polymer since it degrades slowly due to its hydrophobic and semicrystalline nature resulting in generation of less acidic by products. The gel could last more than a month in vivo. However, with most PCL based systems total duration of release is not more than 3 weeks. Slower degradation may lead to accumulation of empty delivery vehicle at the sight of injection. Several investigators have attempted to lower crystallinity of PCL segment to achieve faster degradation in vivo. In one such approach, triblock polymer with random co-polymer of glycolide and caprolactone as hydrophobic segment were synthesized60. Degradation and drug release pattern of hydrogel of poly(ɛ -caprolactone-co-glycolide)-poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(ɛ -caprolactone-co-glycolide) [P(CL-GL)1880-PEG1540-P(CL-GL)1880] triblock copolymer was studied. In an in vitro study polymer degradation occurred at glycolide residues and the pH of medium remained near neutral for initial 8 weeks60. Polymer can be expected to have faster degradation compared to in vitro due to presence of enzymes; nonetheless, it was not studied. BSA was used as model protein to study release pattern at low drug loading of 0.1% w/v in 25 wt% gel. A total of 80 % protein release was obtained over a period of a month via diffusion controlled release mechanism.

Figure 5.

In vitro release of BSA from PCL-PEG-PCL hydrogels in PBS at 37°C with marked copolymer and drug loadings. (A) Effect of different compositions on the BSA release. The copolymer concentration was 20 wt %, and the drug loading was 10.0% (w/w). (B) Effect of varying polymer concentrations on the BSA release from copolymer P2 formulations. Each point represents the mean±SD, n=3. Reproduced with permission from [58].

Thermosensitive hydrogel is simple, elegant and biocompatible aqueous systems, which has shown a few promising results as a standalone system to deliver protein over a period of 2-4 weeks. There are few important aspects, which should be considered during preclinical development. One of the important aspect of protein delivery is to gain high drug loading in formulation. High drug loading can ensure therapeutic concentration over a longer duration. Thermosensitive hydrogel can accommodate proteins in solution form at higher concentration because it is aqueous solution-based system. The system is also devoid of oil/water interface, which have been shown to be detrimental to protein structural integrity. Nonetheless, numerous studies have reported incomplete protein release at higher drug loading. Irreversible protein aggregation (formation of trimers and tetramers) and degradation may be possible explanation of incomplete in vitro release and less than 100% bioavailability in vivo. Such results are observed with a variety of proteins at higher concentration. Hence, it is advisable to have lower drug loading in aqueous solution based hydrogels. Another key aspect that may limit the clinical success of thermosensitive gels is handling of gel during injection is complicated. The polymer is in solution phase at 4°C with good injectability and low viscosity. The solution forms gel at body temperature. However, viscosity of the solution increases as it approaches the room temperature making it difficult to inject59. Sol-to-gel transition is a rapid process. Hence, holding the vial or syringe containing thermosensitive solution may result in accidental formation of gel, which cannot be injected. Regel® hydrogels exhibit reversible sol-to-gel transition but it is an impractical approach in clinical setting. Besides, there are numerous reports available indicating incompatibility of PLGA with proteins. A sophisticated device that maintains temperature of polymer solution should be developed for practical clinical application.

2.3. pH dependent in situ gels

As the name suggest, implant formation and protein release from these implants triggered by change in pH. The systems is composed of polyionic macromolecules (polycation or polyanion) having pH dependent aqueous solubility. Polymer is soluble in water due to ionization of functional groups. Following administration, the pH change leads to precipitation of polymer leading to gel formation. Such polymers include alginates and chitosan. Poly(methacrylic acid) is polyanionic polymer which forms hydrogel at acidic pH (pH<5.8)61.

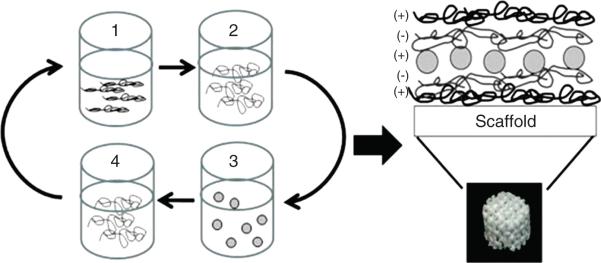

Layer-by-Layer (LbL) coating approach has been utilized to develop protein eluting implants62, 63. Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 (BMP-2) was loaded on implants using polyelectrolyte coating with poly(β-aminoester)/poly2 (polycation) and chondroitin (polyanion) [Figure 6]62. Implant released BMP-2 over a period of 2 week at physiological pH and showed promising results in vivo. In a similar study Poly(L-Lysine) (PLL)/Hyaluronic Acid (HA) coated granules were utilized to deliver BMP-264. Using similar technique surface of anodized titanium Implant was modified to achieve pH dependent protein release65. Implant surface was modified by polyelectrolyte coating of poly-l-histidine (polycation) and poly(methacrylic acid) (polyanion). Fluorescently labeled poly-l-lysine (15−30 kDa) was utilized as model protein to study release from coated implant. LbL-coated implant exhibited pH-dependent release, with maximum release at pH 5−6. It also demonstrated low levels of sustained release at physiological pH (pH 7−8). Length of release and burst release were found to be dependent on molecular weight of poly(methacrylic acid) and method of coating. Later, using the same technology, it was shown that LbL-coated implant can sustain release of BMP-2 and basic fibroblast growth factor over 25 days with nearly identical release profile for both proteins66.

Figure 6.

Schematic of LbL architecture shows that a 3DP scaffold (or glass surface) is repeatedly dipped with tetralayer units consisting of (1) Poly 2 (positively charged), (2) chondroitin sulphate (negatively charged), (3) BMP-2 (positively charged) and (4) chondroitin sulfate. This tetralayer structure was repeated 100 times for all LbL films. Reproduced with permission from [62].

Chitosan is a biocompatible and biodegradable polyamine polysaccharides67. It is soluble at acidic pH owing to ionization of amine groups. However, at physiological pH, ionized amines undergo deprotonation thereby precipitating the polymer to form gel. The gel structure formed by chitosan is porous due to crystallinity of polymer that degrades rapidly under in vivo conditions. Hence, it has limited success in achieving sustained release of proteins. To overcome this limitation, chitosan was cross-linked with polyvinylpyrrolidone using glutaraldehyde to lower crystallinity of chitosan and form gel at physiological pH68. Hydrophobic modification with polyvinylpyrrolidone also provided mechanical strength to the gel structure.

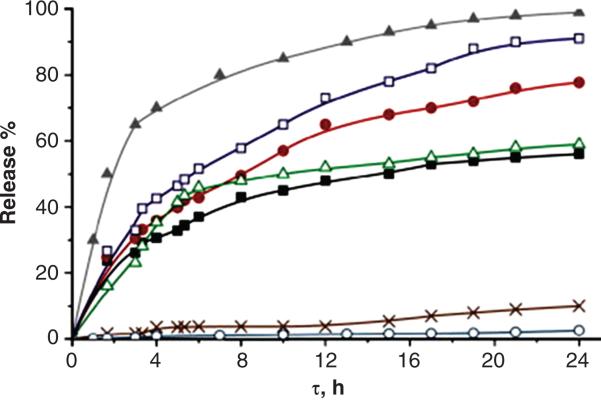

A number of pH sensitive polymers have been developed and investigated for protein delivery via oral route69, 70. However, chemical cross-linking may lead to toxic side effects due to cross-linking agents or unwanted reactions with proteins drugs71. Sergey A et al utilized γ-irradiation to form cross-linked hydrogels consisting of chitosan (CS) and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) for pH sensitive oral delivery of proteins72. The cross-linked hydrogels showed pH dependent swelling with marked swelling under acidic pH. BSA exhibited highest binding with chitosan at pH 5. Absorption of BSA in gel was also directly proportional to porosity of gel, which in turn is dependent on the extent of cross-linking and PVP content. BSA loading in cross-linked gel was driven by charge-charge interactions between CS and BSA molecules. Hence, negligible amount of BSA was released (<10%) from CSPVP hydrogels at acidic pH (pH 1.5), compared to 40-90% released at pH 7.4 within 24 h [Figure 7]72. Similarly, in order to facilitate oral protein delivery and prevent protein degradation at acidic gastric pH, Zhang Y et al developed pH responsive gels using p(PEGMA-g-MAA) with triethylene glycol dimethacrylate as cross-linking agent 73. Hydrogels also exhibited negligible release of model protein BSA at acidic pH and nearly complete release within 12 h, at pH 7.4, suggesting possible application of pH responsive hydrogels in oral protein delivery. No data on protein stability following encapsulation or release was presented.

Figure 7.

BSA release profiles from CSPVP hydrogels at 0.1 M ionic strength. pH 7.4 at 37°C, CSPVP1 (■), CSPVP2 (△), CSPVP3 (●),CSPVP4 (□); release of BSA from hydrogels at pH 1.5 (○), at pH 9 (▲) and in water (x). Key: CSPVP1: Cs:PVP 1:1 w/w crosslinked at 3.2 kGy, CSPVP2: Cs:PVP 1:1 w/w crosslinked at 5 kGy, CSPVP3: Cs:PVP 1:2 w/w crosslinked at 3.2 kGy and CSPVP4: Cs:PVP 1:2 w/w crosslinked at 5 kGy. Reproduced with permission from [72].

As discussed, pH-controlled implants have not been able to provide extended duration of protein release. Hence, hydrophobic polymer was incorporated along with pH sensitive segments to develop pH and temperature sensitive polymers74-80. A pH and temperature sensitive polymer was developed by grafting pH-sensitive sulfamethazine oligomers (SMOs) to thermosensitive poly(ɛ -caprolactone-co-lactide)–poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(ɛ -caprolactone-co-lactide) (PCLA–PEG–PCLA) polymer74. The resulting polymer SMO–PCLA–PEG–PCLA–SMO remained as solution at high pH (pH 8) or at temperatures (70°C). Thus, it was possible to inject the solution at pH 8 with low chance of accidental gel formation during handling. The solution rapidly formed gel upon subcutaneous injection under physiological conditions (pH 7.4 and 37°C) in rats. Injected gel was biocompatible and degraded in 6 weeks with no sign of inflammation. The SMO–PCLA–PEG–PCLA–SMO polymer was studied as a potential injectable scaffold and protein delivery system75. The polymeric hydrogel was capable of encapsulating human mesenchymal stem cells and recombinant human BMP-2 with high encapsulation efficiency. The formulation was examined in vivo and was shown to be effective over 7 weeks following injection.

3. Microparticles

Controlled release of protein from parenteral formulation can be achieved by a matrix-type delivery system. Microsphere formulation holds distinct advantages and has gained popularity in recent years81. More than 200 studies have been published per year pertaining to biodegradable microsphere formulations for peptide and protein delivery. Advantage of employing microspheres formulation for delivery of proteins is that it offers stability for molecules, which are rapidly degraded or eliminated in vivo. Encapsulation in microsphere prevents contact of protein from cells or enzymes such as proteases/esterases in surrounding tissues, until it has been released from microsphere. Microsphere formulation can be easily delivered to the target sites via IV, IM or oral route. Owing to the recent advancements in polymer science and synthesis technology, development of controlled release microsphere formulations has gained immense popularity. The polymers should not produce harmful side effects or toxic degradation products, and neither should it alter any pharmacological properties of the active ingredient. It should also be non-toxic, non-irritant and biocompatible if not biodegradable82. Table 1 summarizes cases with various polymers selected to prepare microspheres for controlled delivery of peptide and proteins including degradation mechanisms.

Table 1.

Various Polymers Used to Prepare Microspheres for Controlled Delivery of Peptide and Proteins.

| Polymer Nature | Material | Degradation Mechanism | Biodegradation | Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Starch | Amylase | Biodegradable | Insulin | 132 |

| Alginate | pH, enzymes | Biodegradable | Protein | 133 | |

| Chitin | pH, enzymes | Biodegradable | Bovine serum albumin (BSA) | 134 | |

| Chitosan | pH, enzymes | Biodegradable | Antigens, Bovine serum albumin, salmon calcitonin | 135 | |

| Collagen/Gelatin | Collegenase | Biodegradable | Hydroxyapatite | 136 | |

| Corn protein (zein) | Enzymes | Biodegradable | Ivermectin | 137 | |

| Cross linked albumin | Enzymes | Biodegradable | Virus antigen | 138 | |

| Hydroxyapatite | Dissolves by the time | Biodegradable | Bone morphogenic protein, Recombinant human glucocerebrosidase | 139, 140 | |

| Hyaluronic acid | Hyaluronidase | Biodegradable | Bovine serum albumin | 141 | |

| Synthetic | Azo-cross-linked copolymer of styrene and HEMA coated particles | Reduction of azo bonds by microflora in large intestine | Partially degradable | Insulin and vasopresin | 142 |

| Maleic anhydride/poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) hybrid hydrogels | Enzymes | Partially degradable | Dextran | 143 | |

| Poly sebacic anhydrides | Hydrolysis | Biodegradable | Rhodamin B | 144 | |

| Polyesters/poly lactides | Ester hydrolysis by esterases | Biodegradable | Somatostatin analogues | 145 | |

| Polyorthoesters | Hydrolysis | Biodegradable | Bovine serum albumin | 146 | |

| Poly lactic acid / glycolic acid (PLGA) | Hydrolysis | Biodegradable | Leuprolide acetate, goserelin acetate, triptorelin, integrilin, insulin | 90, 147 | |

| Polycaprolactones | Hydrolysis | Biodegradable | Bovine serum albumin, insulin, nerve growth factor | 148 | |

| Poly etilen oksit/amino acids | Enzymes | Biodegradable | Poly(L-aspartic acid), Plasmid, DNA, Cyclophosphamide | 149 | |

| Polyphosphazenes | Hydrolysis, dissolution | Biodegradable | Naproxen, Bovine serum albumin | 150, 151 |

Formulation of microspheres from biodegradable polymer is initiated by selecting an appropriate encapsulation method in order to achieve desired/ideal controlled release. Particle size and polydispersity is another important aspect as it directly influences syringeability, which is one of the important requirement for an ideal microsphere system. During microsphere formulation process, there should be no alteration in biological activity of encapsulated protein. Methods in which exposure of protein/peptide in strong denaturing solvent are not employed83.

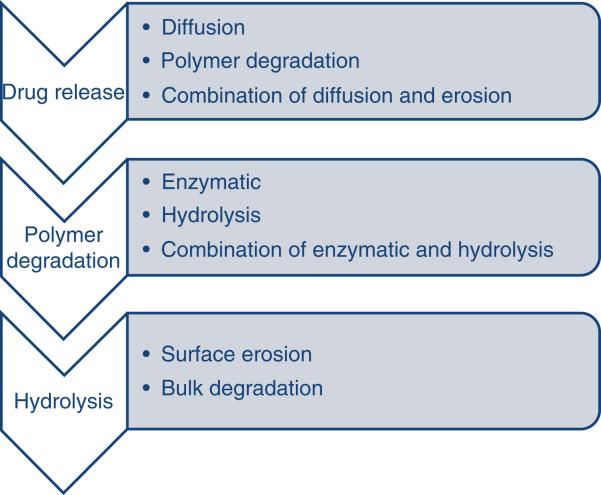

Spray drying method has also been employed in formulating microspheres. Volatile organic solvents such as dichloromethane or acetone are used to dissolve biodegradable polymer. Then the drug is dispersed into the polymer solution in solid form by high-speed homogenization. Volatile organic solvent is then evaporated yielding microspheres of 1 to 100 mm size range. Proteins such as recombinant human erythropoietin were encapsulated in microsphere using spray drying method in nitrogen atmosphere84. Release of active ingredient from microspheres occurs via different mechanisms such as diffusion, polymer degradation, or combination of them85. Graphical representation of different mechanism responsible for drug release through microspheres is shown in [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

Drug release mechanism from microspheres.

Chronic ulcerations of the skin have been reported due to the deficiency of prolidase enzyme. This enzyme is involved in the later stages of protein catabolism. To overcome this problem, PLGA microspheres encapsulating prolidase were formulated by w/o/w multiple emulsion technique. Results obtained from ex vivo studies demonstrated that microencapsulation imparted stability to protein inside the polymer matrix leading to release of active enzyme from the formulation. This technique can be employed for enzyme replacement therapy86.

Similarly, another formulation of PLGA microspheres has been prepared with β-lacto globulin (BLG). Newborns are prone to allergies related to milk proteins, which can be prohibited by prompting oral tolerance to these proteins. PLGA microspheres encapsulating a major allergenic protein, BLG, were formulated by w/o/w double emulsion technique. Controlled release of proteins and higher encapsulation efficiency were reported after introduction of tween 20 in the formulation. Improved encapsulation efficiency and controlled release resulted in the reduction of dose required for specific anti-BLG IgE response following oral administration87.

A microsphere formulation encapsulated with Interferon α (IFN α) and comprising of calcium alginate core surrounded by PELA (poly D, L-lactide-poly ethylene glycol) was prepared by w/o/w multiple emulsion technique. Coated microspheres impart stability to IFN α in the PELA matrix. These microspheres also demonstrated enhanced encapsulation efficiency and retention of biological activity as compared to microspheres produced by conventional method82. In another study, PLGA microspheres encapsulated with salmon calcitonin exhibited 5-9 days release following S.C. injection in rats88. Blends of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) with poly(lactic acid) (PLA) homopolymer and PLGA copolymer were utilized to prepare insulin-loaded microspheres by w/o/w multiple emulsion technique. The resulting microspheres exhibited high entrapment efficiency and provided controlled release of insulin for 28 days89. In another study, ZnO-PLGA microspheres containing insulin demonstrated rapid and long-lasting suppression of glucose levels for 9 days following subcutaneous administration in rats90.

Characteristics of various protein-encapsulated microspheres formulated with various different methods are shown in Table 2. Table 3 summarizes the clinically approved sustained-release microparticle formulations.

Table 2.

Examples of protein-encapsulated microspheres formulated using different methods.

| Release profile and characteristics | Burst release (%) | Particle size (μm) | Polymer | Protein encapsulated | Activity of released protein | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W/O/W Method | ||||||

| Slow release to 55% in 15 days | 38 | 75 | PLGA | Staphylokinase variant K35R (DGR) | Retain ~85% activity on day 15 | 152 |

| Slow release to 65–70% in 14 days | 20-55 | 0.2-167 | PLGA | BSA, VEGF | - | 153, 154 |

| Extremely slow release (linearly) to 12% in 30 days | 3 | 46 | PLGA | BSA | - | 155 |

| Extremely slow release (linearly) to 16% in 30 days | 9 | 19 | PLGA | Lysozyme | - | 155 |

| Extremely slow release to 7.5% in 25 days | 5 | 15 | PLA | Ovalbumin | - | 156 |

| Slow release to 29% in 120 days | 10 | 2-8 | PLA | Tetanus toxoid (TT) | In vivo serum highest anti-TT antibody tires 164 μg/ml | 157 |

| Slow release to 35% in 40 days | 7 | - | PLGA/PLA | Insulin | - | 158 |

| Gradual release to ~55% in 60 days | 20 | 2 | PLGA | Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) | Serum IgG antibody responses up to 12 weeks | 159 |

| Gradual release to ~85% in 35 days | 33 | 28 | PLGA | BSA | - | 160 |

| Gradual release to 90–100% in 24 days | 25-55 | 17-20 | PLGA | BSA | Dematan sulfate reduced insoluble BSA formation | 161 |

| Gradual release to 45–70% in 34 days | 20-40 | 17-24 | PLGA | Insulin | Chondroitin sulfate A preserved secondary structure of insulin up to 20 days | 162 |

| Gradual release to 60% in 11 days | 22 | 75 | PLA | recombinant human epidermal growth factor | Gastric ulcer was cured 82% at day 11 after administration with dose of 220 μg/kg | 163 |

| Gradual release to 63–84% in 30 days | 25-43 | 46-110 | PLGA | Interferon α2b (IFN α2b) | - | 164 |

| Gradual release to 80% in 190 days | 41 | 1.6-2 | PLGA | SPf66 malarial antigen | Retain in vivo activity up to week 27 | 165 |

| Continuous release to 45% in 45 days | <1 | 78 | PLGA and chitosan | BSA | - | 166 |

| Continuous release to 87–95% in 20 days | 4-26 | 35-105 | Acetylated pullulan | Exenatide | No peptide degradation up to day 16 | 167 |

| Nearly zero order release to 95% in 65 days | <5 | 24 | PLGA | Lysozyme | Retain 90% of bioactivity on day 60 | 168 |

| A slow and sustained release of the protein over 20 days without a significant initial burst release | - | 0.4-1.6 | PLGA | Matrix metalloproteinase-3 (MMP-3) | Sustained degradation of fibronectin up to 10 days | 169 |

| S/O/W Method | ||||||

| Initial burst release of approximately 20%, followed by sustained release till 60 days | 20 | 40-100 | PLGA/PLA | Erythropoietin (EPO)-loaded dextran | 170 | |

| Gradual release to 50% in 30 days | 26 | 89 | PLGA | Insulin | In vivo glucose concentration was below 20 mmol/l for 48 hours | 171 |

| Gradual release to 90% in 35 days, no further release in next 25 days | 38 | 5 | PLGA | α-chymotrypsin | - | 172 |

| Gradual release to ~95% in 16 days | 35 | 31 | PLGA | Recombinant human growth hormone | - | 173 |

| Gradual release to 100% in 62 days | 30-35 | 40-100 | PLGA | BSA, horse myoglobin | - | 174 |

| Gradual release to 82% in 30 days, slow release to 100% in next 50 days | 22 | - | PLGA | γ-chymotrypsin | Retain 40% activity on day 7 | 175 |

| Gradual release to 60% in 15 days | 10 | - | PLGA | Insulin | In vivo blood glucose level drop to normal between days 8 and 10 | 176 |

| Gradual release to 97% in 57 days | 7 | 11 | PLGA | Ornitide acetate | - | 177 |

| Nearly zero order release to ~75% in 28 days | 1 | <10 | PLGA, PEG and PLA | Bovine superoxide dismutase (bSOD) | Retain 100% activity in dried microspheres | 178 |

| Nearly zero order release to ~90% in 150 days | 10 | 52 | PLA | Leuprolide | In vivo testosterone levels were suppressed to 0.5 ng/ml from day 4 to day 50 | 179 |

| Gradual release to 100% in 130 days | 20 | 21-24 | PLGA | Bovine insulin | - | 180 |

| W/O/O (Coacervation) and S/O/O Method | ||||||

| Very slow release to 17% in 50 days | 12 | 44 | PLGA | Tenanus toxoid | In vivo tetanus toxin IgG antibody remained ~2 AU/ml for 4 weeks | 181 |

| Fast release to 75% for 25 days followed by slow release to 90% for next 50 days | 25 | 2 | PLGA | Insulin | Secondary structure was maintained after encapsulation | 182 |

| Gradual release to ~75% in 15 days | 20 | 84 | PLGA | Cytochrome C | - | 183 |

| Slow release to 2–14% in 18 days and gradual release to 63% for next 55 days | 6-11 | 123 | PLGA | BSA | - | 184 |

| Gradual release to 19–41% in 28 days | 4-13 | 18-49 | PLGA | Endostatin | - | 185, 186 |

| Gradual release to ~35% in 20 days | 5 | 52 | PLGA | BSA | - | 187 |

| Spray Drying Method | ||||||

| Fast release to ~98% in 8 days | 30 | - | PLGA | BSA | - | 188 |

| Gradual release to 80% in 28 days | 31 | - | PLGA | Vapreotide acetate | - | 145 |

| Gradual release to 94% in 35 days | 8 | 10 | PLGA | Insulin | - | 189 |

| Gradual release to ~100% in 30 days | 26 | - | PLGA | Recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-1 (rhIGF-1) | - | 190 |

| Gradual release to >90% in 35 days | <10 | - | PLGA | Recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor (rhVEGF) | In vivo generate a significant angiogenic response | 191 |

| Gradual release to ~100 in 25 days | 1 | - | PLGA | Recombinant human nerve growth factor (rhNGF) | - | 192 |

| Nearly zero order release to ~80% in 45 days | <10 | 12 | PLGA | Insulin | - | 193 |

| Ultrasonic Atomization Method | ||||||

| Slow release to 20% in 24 days | 5 | 85 | PLGA | Lysozyme | - | 194 |

| Gradual release to ~75% in 28 days, no further release in following Days | 28 | - | PLGA | Vapreotide pamoate | - | 195 |

| Gradual release to ~95% in 98 days | 33 | - | PLA | BSA | - | 195 |

| Gradual release to ~95% in 98 days | - | 36 | PLGA | BSA | - | 196 |

| Other Methods | ||||||

| Fast release to 42–75% in 4 days | 38-53 | 26-128 | PLGA/PLA | recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) | Retain 100% activity after encapsulation | 197 |

| Slow release to ~28% in 3 days | <5 | 40 | PLA | BSA | - | 198 |

| Nearly zero order release to ~70% in 38 days | <1 | 20 | PLGA | BSA | - | 199 |

| Nearly zero order release to ~75% in 38 days | 6.2 | - | PLGA/Pluronic® F127 | rhGH | - | 200 |

| Gradual release to ~100% in 72 days | 22 | 20 | PLA | BSA | - | 201 |

Table 3.

Clinically approved sustained-release microparticle formulations.

| Trade name | Drug | Indications | Delivery System | Length of release | Approval year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lupron Depot® (TAP) | Leuprolide | Prostate cancer, endometriosis | Injectable PLGA microparticles (intramuscular injection) | 1-, 3- and 4-month formulations | 1989 |

| Sandostatin® LAR® (Novartis) | Octreotide | Acromegaly | Injectable PLGA microparticles (intramuscular injection) | 1-month | 1998 |

| Somatuline® LA (Ipsen) | Lantreotide | Acromegaly | Injectable PLGA microparticles (intramuscular injection) | 10-14 days | 1998 |

| Nutropin Depot® (Alkermes/Genentech) | Human growth hormone (hGH) | Growth hormone deficiency | Injectable PLGA microparticles (subcutaneous injection) | 1-month | 1999 |

| Trelstar Depot® (Debiopharm) | Triptorelin | Prostate cancer | Injectable PLGA microparticles (intramuscular injection) | 1- and 3- month formulations | 2000 |

| Risperdal® Consta® (Alkermes/Janssen) | Risperidone | Schizophrenia | Injectable PLGA microparticles (intramuscular injection) | 2 weeks | 2003 |

4. Nanoparticles/Nanospheres

Diameter of smallest capillaries in human body is around 5-6 mm. Polymeric nanoparticles have size of less than 1μm in diameter. These are prepared from natural or synthetic polymers. In order to avoid deleterious effects (such as embolism) due to particle aggregation, the size of particles being administered in bloodstream should be less than 5μm91. Ability to deliver comprehensive range of drugs to different target sites over prolonged period made nanoparticles as a carrier of choice. Different routes can be selected depending on the target site in order to deliver a wide variety of therapeutics via nanoparticles.

Insulin-containing poly (ethyl cyanoacrylate) (PECA) nanoparticles have been investigated to study the effect of several formulation variables. The results obtained demonstrate high yield (90%) with low polydispersity index for nanoparticles. Size of nanoparticles ranged between 130-180 nm, which was influenced by the mass of monomer used in nanoparticle formulation. Similarly, the release rate was also influenced by mass of monomer used in nanoparticle formulation, showing zero-ordered release over 10 days92.

Proteins and peptides exhibit instability in PLGA due to hydrophobic nature of PLGA and acidity of PLGA degradation products93. In addition, burst release of proteins/peptides from PLGA matrices is considered as a major drawback. These concerns have been addressed by a number of investigators by modifying the properties of PLGA matrices94, 95. In a study, BSA was encapsulated in PLGA-PVA composite nanoparticles92. The nanoparticles were having non-porous surface and exhibited extended release of BSA over 2 month. The presence of terminal carboxyl group in PLGA leads to enhanced protein loading and continuous release of protein over 20 days from PLGA nanoparticles96. In contrast, presence of esterified carboxyl end groups in PLGA leads to diminished protein loading and release over 14 day from nanoparticles96.

Fishbein I et al reported release kinetics of nanoparticles encapsulated with PDGF-Receptor β (PDGFRβ) tyrphostin inhibitor, AG-1295. Spontaneous emulsification/solvent displacement technique was employed to formulate AG-1295-loaded poly(DL-lactide) (PLA) nanoparticles. Nanoparticle of 120 nm size showed 25% of burst release followed by gradual release of AG-1295 (50%) over a period of 30 days97. Kawashima Y et al reported a novel delivery system for a physiologically active peptide encapsulated in PLGA nanoparticles (diameter 400 nm). These nanoparticles were formulated by a modified emulsion solvent diffusion method. Glucose level in guinea pigs reduced significantly over 48 h after pulmonary administration of aqueous suspension of PLGA nanoparticles. Formulation produced initial burst release of 85% followed by a sustained release of the remaining drug for a few hours98. With the phase-inversion nanoencapsulation technique zinc-insulin was encapsulated using various polyester and polyanhydride nanoparticle formulations. Insulin release lasted for a short duration (6 h) and released insulin was biologically active99.

PLGA is one of the most widely used biocompatible and biodegradable polymer to prepare nanoparticles. It is also available with varying lactide and glycolide content. However, it causes instability of the encapsulated protein/peptide molecule. For example, release of BSA from PLGA implants prepared by hot-melt extrusion was incomplete. Incomplete release was because of acylation of BSA100. Gaudana et al successfully formulated and characterized hydrophobic ion pairing (HIP) complex of lysozyme (15 kDa), by employing dextran sulfate, a sulfated polysaccharide complexing agent101. Spontaneous emulsion solvent diffusion method was utilized to prepare nanoparticles. Sustained release of lysozyme up to 30 days without significant burst release was observed from the prepared nanoparticles. Released lysozyme as well as lysozyme- dextran sulfate complex sshowed no change in their enzymatic activity. Sustained release of larger protein molecules such as antibodies can be achieved by HIP complexation method101. In another study Gaudana et al successfully formulated and characterized hydrophobic ion pairing (HIP) complex of BSA (66 kDa), by employing dextran sulfate. Solid in oil in water (S/O/W) emulsion method was used to prepare nanoparticles. No change in the secondary and tertiary structure of BSA was reported due to HIP complexation as well as nanoparticle preparation. These results were confirmed by circular dichroism and intrinsic fluorescence analysis102, 103.

5. Miscellaneous Modes of Protein Delivery

5.1. Nanoparticles-in-gel composite systems

A considerable attention has been paid to sustained delivery of protein therapeutics via encapsulating in nano/micro particles. Nano/micro particles provide a stable environment for peptide/protein against catalytic enzymes, allowing improved biological half-lives. However, protein-loaded particulate drug delivery systems exhibited major disadvantage of burst effect (dose dumping) which may result in severe dose related toxicity. Nanoparticle-in-gel composite systems has been investigated to minimize the burst release of proteins and provide localized delivery104, 105.

Posterior segment ocular diseases such as wet age-related macular degeneration (wet-AMD), diabetic retinopathy, and diabetic macular edema are sight-threatening disorders mainly observed in elderly patients. Many protein therapeutics such as bevacizumab, ranibizumab and aflibercept are repeatedly injected (intravitreally) for the treatment of above-mentioned ocular diseases. Repeated intravitreal injections lead to many complications like endophthalmitis, retinal detachment and retinal hemorrhage, and more importantly patient noncompliance. Recently, Mitra et al. have described protein encapsulation in pentablock (PB) polymer nanoparticles dispersed in PB thermosensitive gel for the sustained delivery of proteins following intravitreal delivery106. PB copolymers exhibited excellent biocompatibility with negligible toxicity. A composite formulation (protein-encapsulated PB NPs dispersed in PB thermosensitive gel) exhibited nearly zero order release with no burst effect. Recently, we have discussed the applicability of a PB polymeric nanoparticles and nanoparticles-in-gel composite formulation for the sustained delivery of proteins in the treatment of posterior segment ocular diseases105, 107. Results demonstrated that model proteins (bovine serum albumin, IgG and bevacizumab) -loaded PB composite formulations exhibited nearly zero order release up to 45-60 days. Burst effect in nanoparticles is observed due to immediate release of surface adsorbed proteins. However, when the NPs are dispersed in thermosensitive gel matrix, an additional diffusion layer provided by gelling polymer hinders the release of surface adsorbed drug resulting in elimination of burst effect. In addition, biological activity of the protein molecules was confirmed by in vitro experiments.

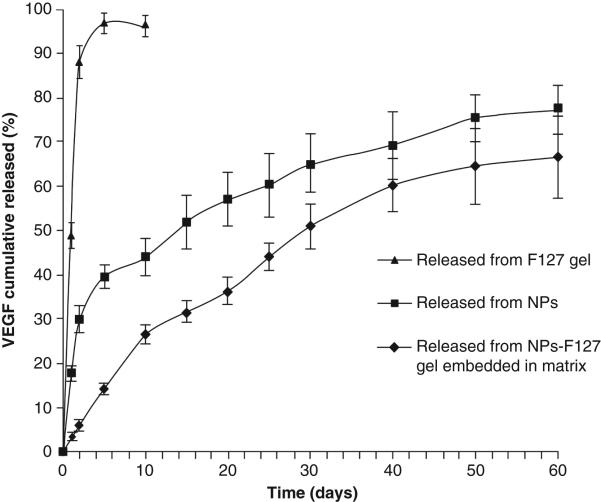

Administration of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in appropriate dose may prove as a promising treatment for the deficient bladder reconstruction therapy. However, short half-lives and high instability due to deamidation, diketopiperazine formation and oxidation of proteins (VEGF) resulted in disappointing clinical trials. Due to high instability, large dose of protein is required which often attributed to sever side effects such as progression of malignant vascular tumors108. In order to achieve sustained release with minimum burst release of VEGF, Geng et al. prepared VEGF-encapsulated PLGA nanoparticles and dispersed them in Pluronic-F127 thermosensitive polymer solutions109. VEGF-NPs exhibited up to ~40% of burst release within the first two days which is significantly reduced to ~15% with the formulation of VEGF-NPs dispersed in thermosensitive gel [Figure 9]109. Controlled delivery of VEGF from a biocompatible delivery system may eliminate the requirement of repeated dosing and possible dose related toxicity. Promising preliminary results observed with the composite delivery system in the treatment of chronic diseases may prove to be cost effective highly patient compliant therapy.

Figure 9.

In vitro release of VEGF from Pluronic-F127 gel, PLGA-NPs and PLGA-NPs dispersed in Pluronic-F127 gel. Reproduced with permission from [109].

5.2. Non-biodegradable implants

Application of non-biodegradable implant for protein and peptide delivery is not prevalent relative to other modes of delivery. Very few systems have been developed so far, despite the systems such as silicone elastomer (non-biodegradable hydrophobic polymer) and osmotic implants are known for a long time. One limitation with these systems is that it requires surgery to administer the implant, which may be complicated or simple procedure depending on the type of disease. Surgical removal of non-biodegradable implant is necessary once the release is complete or in case of any unfavorable/complicated conditions such as infection.

Polysiloxanes, silicones or siloxanes are class of organo-silicon synthetic materials. They have been useful in a wide range of biomedical applications due to their biocompatible nature, low toxicity and inertness. Polymer can be synthesized to impart wide range of properties, ranging from water like liquid, heavy oil-like fluids, greases, rubbers or solid resins depending on the molecular weight of polymer and organic groups attached to silicon atoms. Due to ease of fabrication, a number of delivery systems including matrix, reservoir and drug eluting stents system have been developed to provide controlled release of various therapeutic agents. Hsieh et al first demonstrated applicability of silicon-based polymer implants in protein delivery with model protein BSA110. Kajihara M et al have suggested applicability of silicon-based implant systems for highly potent protein, which would require low dose using interferon as an example111. Interferon was encapsulated in the silicon formulation in solid particle form. Interestingly, release rate was found to be directly proportional to the particle size of encapsulated protein. Release rate was also dependent on protein loading. Release profile was continuous zero-ordered over a month with a total 40% protein release. Higher release rate at large protein particle size and loading was attributed to formation of a large number of interconnected channels upon protein release. In addition, it was shown that the release rate could be further accelerated by simple addition of glycine to the interferon particles. Presence of glycine, as low as 2%, drastically enhanced release rates. Drug release mechanism was attributed to the formation of interconnected channels in implant upon initial protein release. These channels allowed dissolution of protein inside implant causing a rise in osmotic pressure leading to formation of cracks, which further facilitated release. To further control the release of interferon, covered-rod-type implants were developed112. Interferon release from these implants was highly tunable with addition of presence of various additives, protein content (% loading) and surface area of implant. Covered-rod-type formulation released interferon at a constant rate over 30–100 days in vitro without significant initial burst. The release rate was correlated to the osmotic pressure, i.e., higher the osmotic pressure, higher the release rate. Pharmacokinetic studies in mice showed detectable levels of interferon after 60 days111. Interferon released from this formulation exhibited very high antitumor activity in nude mice tumor model following a S.C. administration. Tumor suppression was observeed for more than 100 days111. Maeda H et al also developed covered-rod-type formulation with silicone polymer to investigate controlled release of small and protein (BSA) molecules113. Sucrose was used as additive and encapsulated along with BSA in the implants. Again, the release was very tunable in these systems113. In another study, matrix type and covered rod type injectable implants were compared to deliver protein using either the model antigen avidin or clostridium tetani and clostridium novyi toxoids in sheep114. The matrix type implants delivered antigen in vitro in a first-ordered manner over a period of a month. In contrast, covered rod type implant released low amounts of antigen at zero order for longer duration. Covered-rod-type implants were shown to produce better immune response from antigen exposure for longer duration and favored production of both IgG1 and IgG2 isotypes. Thus, silicon-based implants have shown promising results in controlling protein release over a period of months, both in vitro and in vivo. Most of these systems also exhibited nearly complete release of proteins, which could be a significant advantage in addition to biocompatible and nontoxic nature of these systems. Furthermore, implants can be prepared under mild conditions without heat and organic solvents, which are known to degrade proteins112.

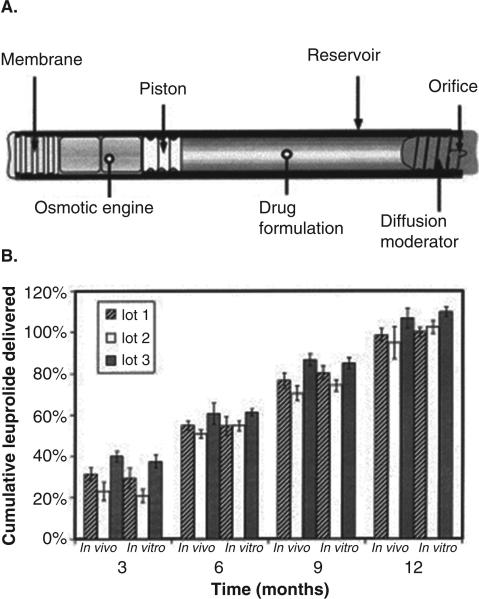

Zero-ordered delivery is the most desired property of an extended release formulation. Zero-ordered release ensures that drug concentration will remain within the therapeutic window, without reaching toxic or subtherapeutic levels. Osmotically controlled, mechanical devices, “nonbiodegradable” implants have been designed for extended delivery at a constant rate. These systems have been shown to be biocompatible and effective to provide constant therapeutic concentrations in a number of animal and human trials115-120. Some of the osmotically-driven implants include Duros® (DURECT), ALZET® (veterinary medicine, research application) and Viadur® (leuprolide acetate, marketed formulation)120. Precise control over drug release for extended duration (months to year) is achieved by osmotic pressure. For example, Duros® implant is a cylindrical (4 mm in OD and 45 mm in length), developed for human use and can be implanted subcutaneously117. As illustrated in Figure 10a, the implant consists of an osmotic engine (chamber containing sodium chloride, osmotic agent), a piston and a reservoir chamber for drug117. A semipermeable rate-controlling membrane covers the side of cylinder housing osmotic engine. Presence of osmotic agent causes water to permeate through the semipermeable membrane. The osmotic pressure then pushes the piston towards drug chamber that in turn allow drug release through a small opening on the reservoir side of implant. The volume of drug reservoirs is ~150 μL, thus implant is best suited for potent therapeutics. Viadur® is an adaptation of the DUROS® Implant technology to deliver leuprolide acetate for the treatment of prostate cancer. Leuprolide release was observed for 1 year at constant rate at 37°C in unstirred phosphate-buffered saline117. Similar in vitro release profiles have been observed with sufentanil from the DUROS Chronogesic system121 and interferon from the OMEGA DUROS system115. Nevertheless, most impressive character of these implants is the IVIVC of release data, which simplifies the process of implant development. Figure 10b illustrates in vivo/in vitro performance comparison for cumulative drug delivery in rats117. The results showed a good agreement between cumulative delivery in vivo and in vitro over a period of 12 months. Moreover, the release rates were also very comparable between in vitro and in vivo release from different batches. Similar studies in canines also showed similar trends. Good agreement in IVIVC may be attributed to the stability of peptide throughout the release period. Stability of protein/peptide for such extended duration is very critical for the success of such implant systems.

Figure 10.

(a) Cross-sectional diagram of the DUROS ® implant. (b) In vivo/in vitro performance comparison for cumulative drug delivery in rats. Reproduced with permission from [117].

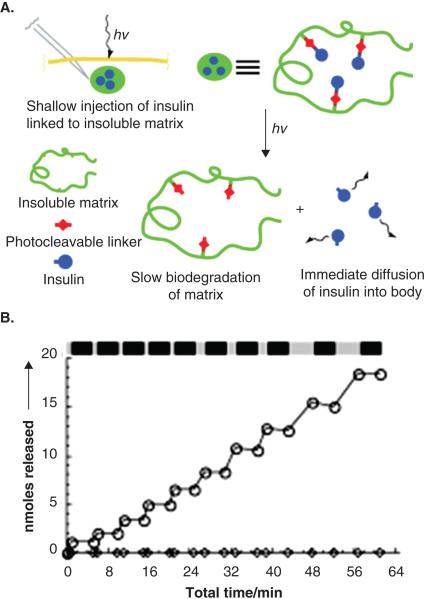

5.3. Photoactivated Depots

A novel delivery system to control delivery of insulin external stimulus has been developed122. Daily multiple administration of insulin is a primary treatment strategy for type 1 diabetes. It is possible to self-administer insulin; nonetheless, multiple injections every day is a significant lifetime burden on patients. In order to minimize number of administrations and control plasma insulin levels, photoactivated depot (PAD) was developed. PAD consists of insulin chemically conjugated to an insoluble, biodegradable resin via photo-labile group [Figure 11a]122. PAD can be injected subcutaneously and insulin release can be controlled externally using irradiation. In an in vitro release study investigators showed that insulin release was completely dependent on irradiation (LED at 365 nm) [Figure 11b]122. In absence of irradiation, no insulin release was observed. Insulin is suitable to this approach, since only a small amount is required daily. It may be difficult to utilize such technique for larger proteins. Drug loading may be an issue for peptides, which require higher plasma concentrations. In this case, the size of the depot may be larger and hence irradiation at longer wavelength may be required to cause deep tissue penetration.

Figure 11.

(a) Overall approach to the photoactivated depot (PAD). A drug, insulin in this case, is linked to an insoluble but biodegradable resin, through a photocleavable linker. The conjugate is injected in a shallow depot cutaneously or subcutaneously. Irradiation breaks the link of insulin from the resin, thereby allowing it to diffuse away from the resin and be absorbed by the systemic circulation. Ultimately the resin is biodegraded. (b) Stepwise photolysis of the photoactivated insulin depot. Cumulative moles of insulin released from the modified resin when using an LED point source that was turned on and off repeatedly. Light and dark bars indicate periods of irradiation and darkness. Reproduced with permission from [122].

6. Expert Opinion