Abstract

Background

Prior studies have reported higher HIV prevalence among prisoners than the general population in Brazil, but data have been derived from single prisons. The aim of this study was to evaluate HIV testing practices, prevalence and linkage to care among inmates in a network of 12 prisons.

Methods

We administered a questionnaire to a population-based sample of inmates from 12 prisons in Central-West Brazil and collected sera for HIV and syphilis testing from January to December 2013. We evaluated factors associated with HIV testing and infection using multivariable logistic regression models. Six months after HIV testing, we assessed whether each HIV-infected prisoner was engaged in clinical care and whether they had started antiretroviral therapy.

Results

We recruited 3,362 inmates, of whom 2,843 (85%) were men from 8 prisons, and 519 (15%) were women from 4 prisons. Forty-five percent of participants reported never having been tested for HIV previously. In multivariable analysis, the variables associated with previous HIV testing were lack of a stable partner (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 1.38; 95% CI: 1.18–1.60), completed more than four years of schooling (AOR 1.40; 95% CI: 1.20–1.64), history of previous incarceration (AOR: 1.68; 95% CI: 1.43–1.98), history of mental illness (AOR 1.52; 95% CI: 1.31–1.78) and previous surgery (AOR 1.31; 95% CI: 1.12–1.52). Fifty-four (1.6%) of all participants tested positive for HIV; this included 44 (1.54%) men and 10 (1.92%) women. Among male inmates, HIV infection was associated with homosexuality (AOR 6.20, 95% CI: 1.73–22.22), self-report of mental illness (AOR 2.18, 95% CI: 1.13–4.18), history of sexually transmitted infections (AOR 3.28, 95% CI: 1.64–6.56), and syphilis sero-positivity (AOR 2.54, 95% CI: 1.20–5.39). Among HIV-infected individuals, 34 (63%) were unaware of their HIV status; only 23 of these 34 (68%) newly diagnosed participants could be reached at six month follow-up, and 21 of 23 (91%) were engaged in HIV care.

Conclusions

HIV testing rates among prison inmates are low, and the majority of HIV-infected inmates were unaware of their HIV diagnosis. Incarceration can be an opportunity for diagnosis and treatment of HIV among vulnerable populations who have poor access to health services, but further work is needed on transitional HIV care for released inmates.

Introduction

The prison population is growing throughout the world, with an estimated populace of 10.2 million people [1]. According to the International Centre for Prison Studies (ICPS) [2], Brazil currently has the fourth largest prison population in the world (548,003 persons in penal institutions), preceded by the United States (2,228,424), China (1,701,344), and Russia (676,400). Within Brazil, the state of Mato Grosso do Sul had the highest rate of incarceration in the country, at 497 inmates per 100,000 inhabitants in 2012 [3].

Globally, prisoners have been consistently observed to have higher rates of HIV compared with the general population [4–6]. This increased prevalence has been associated with risk behaviors of inmates both prior to and during incarceration, such as intravenous drug use, needle sharing, tattooing in unsafe conditions and unsafe sexual practices [7, 8]. In the absence of public health interventions, overcrowded prisons with high rates of undiagnosed HIV infection may serve as foci for HIV transmission. On the other hand, correctional facilities could serve as sites for the timely diagnosis and treatment of HIV [9, 10]. For some inmates, arrest and introduction into a penal institution may lead to their first interaction with health services [11], representing an opportunity to provide testing to an otherwise hard-to-reach population.

In Brazil, HIV prevalence among inmates has been estimated at 3–16%, but nearly all studies have been small, single-prison investigations. We conducted a cross-sectional study in 12 Brazilian prisons to evaluate HIV testing practices among inmates, to estimate the prevalence of HIV among male and female prisoners, to assess risk factors for HIV infection, and to evaluate linkage to care among HIV-infected inmates.

Methods

Study setting and design

The state of Mato Grosso do Sul, located in Central-West Brazil with a population of 2.5 million people, had an inmate population of over 12,000 in 2013. The penal system is comprised of “closed” and “open” subsets to segregate high and low-risk offenders (the latter of whom are allowed to leave the prison during daytime hours); 9,913 inmates in 22 penitentiaries comprise the total closed subset. Twelve prisons were selected from a cross-sectional study performed in the population of the closed system in the 5 largest cities in the state (Campo Grande, Corumbá, Dourados, Ponta Porã and Três Lagoas) from January through December 2013 and included in the present study. The study population, 7,221 inmates, represents 59% of the total state inmate population and 73% of inmates in the closed subset. Of the 12 study prisons, eight prisons (including 6,552 inmates) housed men and four prisons (including 669 inmates) housed women.

Proportional stratified sampling was performed by using each prison as a unit of randomization. At the time of data collection, inmates were ordered numerically based on roll call lists provided by the prison administrators and a list of random numbers was generated using Epi-Info 6.04 software (Atlanta, GA, USA). The sample size was calculated using an expected 2% prevalence for HIV, with a variation of 1%, a power of 80%, and an alpha typeerror of 5%. An additional 20% individuals from each prison were included to account for anticipated loss due to refusal to participate. Only prisoners who were at least 18 years of age at time of study commencement and who consented to participate were included in the study.

Data collection

Each participant underwent an interview utilizing a standardized questionnaire. The variables obtained during the interview included age, sex, marital status, educational attainment, drug use, sexual history, history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), blood transfusion, tattoos, piercings, previous surgery, self-reported mental illness, previous incarceration and time in the prison. The participant’s race/ethnicity (i.e., white, black, indigenous, Asian or mixed) was self-reported.

HIV and syphilis testing

After appropriate antisepsis, a peripheral venous blood sample (10 mL) was obtained using a vacuum tube system. Blood samples were transferred to the Laboratory of Clinical Immunology of Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), processed to obtain serum, then aliquoted and stored at -20°C until the completion of serological assays.

Serum samples of participants were initially screened with a commercial enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for detection of antibodies against HIV-1 and HIV-2 (Murex HIV-1.2.0, DiaSorin, Italy). All positive and indeterminate specimens were confirmed by Western blot assay (Novopath HIV-I, Immunoblot, BioRad).

Syphilis exposure was tested for using a treponemal antibody ELISA (ICE* Syphilis®, DiaSorin, Italy), which assays for IgG or IgM to recombinant treponemal antigens; a positive test indicates prior infection with syphilis but cannot distinguish active infection from treated cases.

All prisoners with a positive HIV test underwent counseling and medical consultation after the test results and were referred for follow-up in specialized service for treatment of HIV / AIDS. Six months after diagnosis, we followed up with the prison health service, the antiretroviral therapy delivery database system (SICLOM) [12], Laboratory Test Database System (SISCEL) [13] and the specialized service for the treatment of HIV / AIDS (SAE) in each city to determine whether HIV-infected prisoners were engaged in care and whether they had started antiretroviral therapy.

Data analysis

All questionnaires were double entered in Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). After entry, data were compared to search for data entry errors. SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used to analyze the bivariable and multivariable models. The prevalence of HIV was expressed as the percentage among inmates screened with cluster-adjusted 95% confidence-intervals. Dichotomized and categorical data were analyzed with the chi-squared test, and t-test was used to analyze continuous variables. Bivariable logistic regression was utilized to verify the association between HIV and socio-demographic factors, self-reported risk factors, and syphilis infection. Variables achieving a pre-specified level of significance (p<0.2) in bivariable analysis were included in a multivariable model, which was then trimmed using stepwise backward logistic regression and results were expressed in odds ratios (OR) and adjusted odds ratios (AOR).

Ethical issues

All eligible participants provided written informed consent prior to study participation. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the Federal University of Grande Dourados (Number 191,877). The results of the serological tests were delivered directly to the prisoners by an infectious disease physician and the prisoners were referred for specialist treatment.

Results

Demographic Characteristics and Risk Behaviors

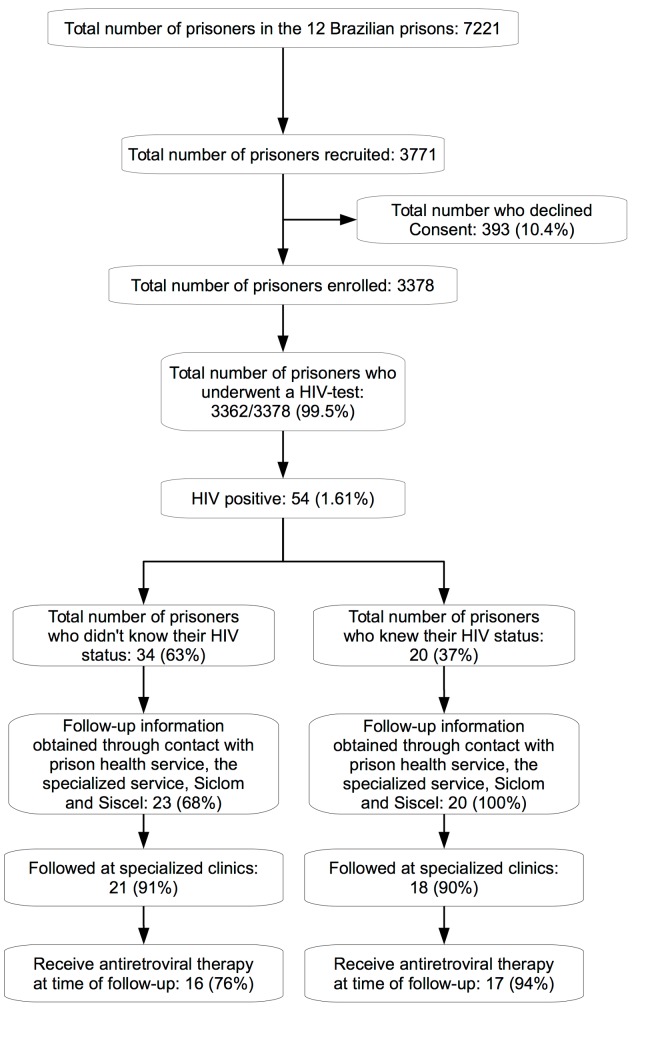

A total of 3,771 individuals were recruited from the 12 prisons; 393 (10.4%) individuals declined to participate in the study, and 16 (0.5%) individuals refused blood collection. Interviews were performed and blood samples collected for 3362 inmates (Fig 1). The majority of study enrolled were men (2,858; 85%), and the mean age was 32 years (SD: ±10 years, range: 18–80 years) (Table 1). Participants primarily (64%) identified as being originally from Mato Grosso do Sul, and self-reported as belonging to white (33%), mixed (51%), black (13%), indigenous (1%) and Asian (2%) ethnic backgrounds. Approximately 45% of participants reported more than four year of schooling. Drug trafficking was the most common reason for incarceration (1,525; 45%) (Tables 1 and 2).

Fig 1. Flow chart of the study enrollment and screening process for HIV.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and risk behaviors variables in 8 male Brazilian prisons.

| Variables | Prison | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPC | PTL | EPRB | PHAC | CTAL | PTCG | IPCG | EPJFC | |

| Location | Corumbá | TrêsLagoas | Ponta Porã | Dourados | Campo Grande | Campo Grande | Campo Grande | Campo Grande |

| Prisoner population | 364 | 436 | 299 | 1,826 | 144 | 398 | 1,098 | 1,987 |

| Enrolled subjects | 263 | 282 | 252 | 539 | 116 | 286 | 517 | 603 |

| HIV positive | 4 (1.5) | 5 (1.8) | 3 (1.2) | 10 (1.8) | 3 (2.6) | 5 (1.7) | 8 (1.5) | 6 (1.0) |

| Never previously tested for HIV | 144 (54.7) | 116 (41.1) | 127 (50.4) | 228 (42.3) | 51 (44.0) | 178 (62.2) | 225 (43.5) | 327 (54.2) |

| Syphilis sero-positivity | 34 (12.9) | 26 (9.2) | 31 (12.3) | 46 (8.5) | 12 (10.3) | 28 (9.8) | 48 (9.3) | 47 (7.8) |

| Sociodemographic | ||||||||

| Age, years, mean±SD | 32.6 (10.0) | 31.9 (10.1) | 33.8 (10.7) | 31.5 (9.4) | 35.8 (10.1) | 28.9 (9.7) | 34.0 (10.0) | 30.8 (8.1) |

| Marital status, Single | 146 (55.5) | 145 (51.4) | 121 (48.0) | 286 (53.0) | 51 (44.0) | 166 (58.0) | 252 (48.7) | 355 (58.9) |

| Previous incarceration | 156 (59.3) | 168 (59.6) | 98 (38.9) | 349 (64.7) | 71 (61.2) | 132 (46.1) | 332 (64.2) | 450 (74.6) |

| Reside in Mato Grosso do Sul | 180 (68.4) | 148 (52.5) | 119 (47.2) | 372 (69.0) | 85 (73.3) | 206 (72.0) | 364 (70.4) | 414 (68.6) |

| More than 4 year of schooling | 111 (42.2) | 124 (44.0) | 144 (57.1) | 199 (36.9) | 59 (50.9) | 134 (46.8) | 190 (36.7) | 241 (39.9) |

| Drug use over the last year | 110 (41.8) | 158 (56.0) | 93 (36.9) | 283 (52.5) | 47 (40.5) | 158 (55.2) | 271 (52.4) | 419 (69.5) |

| IDU over the last year | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.7) | 9 (1.7) | 9 (1.5) |

| Sexual History | ||||||||

| Sexual preference, homosexual | 7 (2.7) | 5 (1.8) | 3 (1.2) | 6 (1.1) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (1.0) | 20 (3.9) | 3 (0.5) |

| Previously had homosexual intercourse | 30 (11.4) | 14 (5.0) | 7 (2.8) | 16 (3.0) | 2 (1.7) | 16 (5.6) | 53 (10.2) | 16 (2.6) |

| Ever had sex with drug user | 80 (30.4) | 121 (42.9) | 76 (30.1) | 225 (41.7) | 24 (20.7) | 69 (24.1) | 153 (29.6) | 208 (34.5) |

| Ever had sex with an IDU | 6 (2.3) | 8 (2.8) | 2 (0.8) | 12 (2.2) | 4 (3.4) | 7 (2.4) | 26 (5.0) | 17 (2.8) |

| No stable partner | 143 (54.4) | 140 (49.6) | 125 (49.6) | 274 (50.8) | 41 (34.5) | 130 (45.4) | 245 (47.4) | 317 (52.6) |

| Condom use, Sometimes/never | 187 (71.1) | 205 (72.7) | 181 (71.8) | 367 (68.0) | 72 (62.0) | 159 (55.6) | 336 (65.0) | 381 (63.2) |

| History of STI(s) | 41 (15.6) | 39 (13.8) | 44 (17.5) | 66 (12.2) | 13 (11.2) | 23 (8.0) | 57 (11.0) | 60 (9.9) |

| Other Risk Behavior | ||||||||

| Blood transfusion | 22 (8.4) | 36 (12.7) | 23 (9.1) | 67 (12.4) | 18 (15.5) | 30 (10.5) | 84 (16.2) | 73 (12.1) |

| Tattoos | 171 (65.0) | 191 (67.7) | 111(44.0) | 373 (69.2) | 62 (53.4) | 187 (65.4) | 341 (65.9) | 477 (79.1) |

| Piercings | 27 (10.3) | 25 (8.9) | 7 (2.8) | 22 (4.1) | 109 (94.0) | 253 (88.5) | 485 (93.8) | 541 (89.7) |

| Surgery | 94 (35.7) | 103 (36.5) | 96 (38.0) | 192 (35.6) | 49 (42.2) | 111 (38.8) | 239 (46.2) | 234 (38.8) |

| Self-reported mental illness | 114 (43.3) | 120 (42.5) | 78 (30.9) | 196 (36.4) | 49 (42.2) | 111(38.8) | 221 (42.7) | 259 (42.9) |

Abbreviations: HIV- Human Immunodeficiency vírus, SD–Stardard deviation, IDU–Intravenous drug user, STI–Sexually transmitted infections, EPC—Estabelecimento Penal de Corumbá, PTL—Penitenciária de Três Lagoas, EPRB—Estabelecimento Penal Ricardo Brandão, CTAL—Centro de Triagem Anízio Lima, PTCG—Presídio de Transito de Campo Grande, IPCG—Instituto Penal de Campo Grande, PHAC—Penitenciária Harry Amorim Costa and EPJFC—Estabelecimento Penal Jair Ferreira de Carvalho.

Table 2. Sociodemographic and risk behaviors variables in 4 female Brazilian prisons.

| Variables | Prison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPFCAJG | EPFTL | EPFPP | EPFIIZ | |

| Location | Corumbá | TrêsLagoas | Ponta Porã | Campo Grande |

| Prisoner population | 113 | 82 | 99 | 375 |

| Enrolled subjects | 81 | 76 | 94 | 269 |

| HIV positive | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.1) | 6 (2.2) |

| Never previously tested for HIV | 24 (29.6) | 10 (13.1) | 19 (20.2) | 73 (27.1) |

| Syphilis sero-positivity | 8 (9.8) | 14 (18.4) | 11 (11.7) | 55 (20.4) |

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Age, years, mean±SD | 31.8 (9.9) | 31.9 (9.9) | 31.9 (12.1) | 31.7 (9.4) |

| Marital status, Single | 50 (61.7) | 48 (63.1) | 62 (65.9) | 173 (64.3) |

| Previous incarceration | 22 (27.2) | 28 (36.8) | 28 (29.8) | 130 (48.3) |

| Reside in Mato Grosso do Sul | 30 (37.0) | 42 (55.3) | 39 (41.5) | 167 (62.0) |

| More than 4 year of schooling | 49 (60.5) | 33 (43.4) | 59 (62.8) | 141 (52.4) |

| Drug use over the last year | 14 (17.3) | 27 (35.5) | 39 (41.5) | 119 (44.2) |

| IDU over the last year | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (1.1) |

| Sexual History | ||||

| Sexual preference, homosexual | 4 (4.9) | 9 (11.8) | 4 (4.2) | 41 (15.2) |

| Previously had homosexual intercourse | 19 (23.4) | 19 (25.0) | 20 (21.3) | 67 (24.9) |

| Ever had sex with drug user | 22 (27.2) | 43 (56.6) | 53 (56.4) | 138 (51.3) |

| Ever had sex with an IDU | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.6) | 3 (3.2) | 25 (9.3) |

| No stable partner | 45 (55.5) | 41 (53.9) | 52 (55.3) | 140 (52.0) |

| Condom use, Sometimes/never | 63 (77.8) | 57 (75.0) | 63 (67.0) | 169 (62.8) |

| History of STI(s) | 2 (2.5) | 8 (10.5) | 2 (2.1) | 39 (14.5) |

| Other Risk Behavior | ||||

| Blood transfusion | 13 (16.0) | 11 (14.5) | 7 (7.4) | 28 (10.4) |

| Tattoos | 39 (48.1) | 55 (72.4) | 54 (57.4) | 176 (65.4) |

| Piercings | 16 (19.7) | 38 (50.0) | 42 (44.7) | 90 (33.4) |

| Surgery | 51 (63.0) | 52 (68.4) | 61 (64.9) | 164 (61.0) |

| Self-reported mental illness | 37 (45.7) | 38 (50.0) | 58 (61.7) | 138 (51.3) |

Abbreviations: HIV- Human Immunodeficiency vírus, SD–Stardard deviation, IDU–Intravenous drug user, STI–Sexually transmitted infections, EPFCAJG—Estabelecimento Penal Feminino Carlos Alberto Jonas Giordano, EPFTL—Estabelecimento Penal Feminino de Três Lagoas, EPFPP—Estabelecimento Penal Feminino de Ponta Porã, EPFIIZ—Estabelecimento Penal Feminino Irmã Irma Zorzi.

In regards to risk behaviors, half of those surveyed (1,693; 50%) reported not having a regular partner. Approximately 3% (106) of participants self-identified as homosexual, and 8% (279) reported having engaged in a homosexual intercourse. A history of any homosexual intercourse was reported more commonly among women (24%) than men (5%). Condom use was reported as irregular by 2,240 (66%) inmates, and 394 (12%) reported history of STIs. Syphilis serology was positive in 272 (9.5%) male and 88 (17%) female inmates. More than half (66%) reported having tattoos, 42% reported any mental illness and any drug use in the past year was reported among 1,738 (51%) inmates, but intravenous drug use was largely uncommon (31; 0.9%). The majority of inmates reported previous incarceration (1,964; 58%) (Tables 1 and 2).

HIV Testing

Nearly half of inmates had never been previously tested for HIV (1,522; 45%); this ranged from 13.1% (Estabelecimento Penal Feminino de Três Lagoas) to 62.2% (Presídio de Transito de Campo Grande) among the different prisons (Tables 1 and 2). In multivariable analysis, the variables associated with previous HIV testing were lack of a stable partner (AOR: 1.38; 95% CI: 1.18–1.60), more than four years of schooling (AOR 1.40; 95% CI: 1.20–1.64), history of previous incarceration (AOR: 1.68; 95% CI: 1.43–1.98), history of mental illness (AOR 1.52; 95% CI: 1.31–1.78) and previous surgery (AOR 1.31; 95% CI: 1.12–1.52; Table 3).

Table 3. Variables associated with previous HIV testing among prisoners (N = 3,362).

| Variables | Crude OR | Adjusted OR |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, female | 3.18 (2.54–3.99) | |

| Age, per year | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | |

| Marital status, single | 0.79 (0.69–0.90) | |

| Reside in Mato Grosso do Sul | 0.80 (0.67–0.90) | |

| More than 4 year of schooling | 1.40 (1.21–1.61) | 1.40 (1.20–1.64) |

| Drug use over the last year | 0.85 (0.74–0.97) | |

| Ever shared needles/syringes | 0.91 (0.61–1.35) | |

| Sexual preference—homosexual | 2.05 (1.34–3.14) | |

| Ever had homosexual intercourse | 1.85 (1.43–2.41) | |

| Ever had sex with a drug use | 1.16 (0.79–1.70) | |

| Ever had sex with an IDU | 1.16 (0.79–1.70) | |

| No Stable Partner | 1.35 (1,18–1,55) | 1.38 (1.18–1.60) |

| Condom use, sometimes/never | 1.07 (0.92–1.24) | |

| History of STI(s) | 1.30 (1.03–1.59) | |

| Blood transfusion | 1.52 (1.23–1.89) | |

| Tattoos | 0.90 (0.78–1.04) | |

| Piercings | 1.20 (0.97–1.49) | |

| Shared objects | 1.10 (0.74–1.63) | |

| Surgery | 1.59 (1.38–1.83) | 1.31 (1.12–1.52) |

| Self-reported mental illness | 1.58 (1.37–1.82) | 1.52 (1.31–1.78) |

| Previous incarceration | 1.40 (1.23–1.62) | 1.68 (1.43–1.98) |

| Time in prison, per month | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) |

Abbreviations: OR—odds ratio, IDU—intravenous drug user, STI—sexually transmitted infections.

HIV Prevalence, Risk Factors and Linkage to Care

Among the 3362 participants, 54 (1.61%, 95% CI: 1.21%-2.10%) tested HIV-positive: 44 (1.54%; 95% CI: 1.12%-2.07%) men and 10 women (1.92%; 95% CI: 0.92%-3.53%). In bivariable analysis, male inmates who were single (OR 1.93, 95% CI: 1.02–3.64), identified as homosexual (OR: 8.39, 95% CI: 3.15–22.34), reported no stable partner (OR: 2.05, 95% CI: 1.10–3.84), had a history of STIs (OR: 3.68, 95% CI: 1.95–6.94), had positive syphilis serology (OR 3.61, 95% CI: 1.84–7.08) or had self-reported mental illness (OR: 2.26, 95% CI: 1.23–4.17) were more likely to be infected with HIV (Table 4). Among female inmates, only self-reported history of STIs was associated with HIV (OR: 30.27, 95% CI: 5.93–154.38). In multivariable analysis, homosexuality (AOR: 6.20, 95% CI: 1.73–22.22), history of STIs (AOR: 3.28, 95% CI: 1.64–6.56), positive syphilis serology (AOR: 2.54, 95% CI: 1.20–5.39) and history of mental illness (AOR: 2.18, 95% CI: 1.13–4.18) were positively associated with HIV infection among men. There were too few female HIV-infected inmates for multivariable analysis to provide reliable risk factor estimates.

Table 4. Risk factors associated with HIV among male and female prisoners (N = 3,362).

| Male (N = 2,843) | Female (N = 519) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | Crude OR |

| Age, per year | 0.98 (0.95–1.00) | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | |

| Marital status, single | 1.93 (1.02–3.64) | 4.79 (0.60–38.14) | |

| Reside in Mato Grosso do Sul | 1.30 (0.71–2.38) | 0.76 (0.21–2.71) | |

| More than 4 year of schooling | 0.64 (034–1.22) | 0.35 (0.09–1.37) | |

| Drug use over the last year | 1.03 (0.57–1.85) | 0.93 (0.26–3.35) | |

| Ever shared needles/syringes | 0.61 (0.14–2.57) | 0 | |

| Sexual preference—homosexual | 8.39 (3.15–22.34) | 6.20 (1.73–22.22) | 1.97 (0.41–9.52) |

| Ever had homosexual intercourse | 2.42 (0.94–6.26) | 0.93 (0.18–4.65) | |

| Ever had sex with a drug use | 0.75 (0.42–1.38) | 0.99 (0.28–3.45) | |

| Ever had sex with an IDU | 0.84 (0.11–6.18) | 4.06 (0.82–20.04) | |

| No Stable Partner | 2.05 (1.10–3.84) | 2.06 (0.53–8.04) | |

| Condom use, sometimes/never | 0.53 (0.29–0.95) | 1.63 (0.33–7.95) | |

| History of STI(s) | 3.68 (1.95–6.94) | 3.28 (1.64–6.56) | 30.27 (5.93–154.38) |

| Syphilis-positive | 3.61 (1.84–7.08) | 2.54 (1.20–5.39) | 3.36 (0.93–12.18) |

| Blood transfusion | 1.15 (0.45–2.94) | 0.29 (0.07–1.16) | |

| Tattoos | 0.46 (0.25–0.83) | 0.59 (0.17–2.07) | |

| Piercings | 0.99 (0.30–3.21) | 5.19 (0.65–41.26) | |

| Shared objects | 0.66 (0.34–1.29) | 0.93 (0.27–3.27) | |

| Surgery | 1.06 (0.58–1.95) | 0 | |

| Self-reported mental illness | 2.26 (1.23–4.17) | 2.18 (1.13–4.18) | 0.91 (0.26–3.18) |

| Previous incarceration | 1.09 (0.59–1.98) | 0.66 (0.19–2.32) | |

| Time in prison, per month | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.98 (0.95–1.01) | |

Abbreviations: OR—odds ratio, IDU—intravenous drug user, STI—sexually transmitted infections.

Among the 54 individuals who tested positive for HIV, 34 (63%) were unaware of their diagnosis, and among these, 15 (44%) had never been previously tested for HIV. All 34 individuals who were diagnosed with HIV underwent medical examination and were referred to the HIV/AIDS referral service. After 6 months, 23 could be contacted for follow up: 21 of 23 (91%) individuals contacted had been seen in an HIV specialty clinic and 16 (76%) had started antiretroviral therapy. Among the 20 individuals who already knew their diagnosis, 18 (90%) were being followed in HIV specialized clinics and 17 (85%) were receiving antiretroviral therapy (Fig 1).

Discussion

Globally, prison inmates are a consistently high-risk and yet underserved population for HIV, despite years of emphasis on the need for increased HIV testing and prevention in this setting [14]. Critically, nearly half of individuals in this high-risk population had never been tested for HIV, and the majority of individuals identified with HIV were not aware of their HIV status. These findings underscore the continued gap in HIV services for this population.

Prior studies in Brazil have reported HIV prevalence ranging from 1.2–16.0% in men [9, 15–20] and 9.9–13.9% in women [7, 21]. In this study of twelve prisons in Mato Grosso do Sul, we detected HIV infection among 1.54% of male inmates and 1.92% of female inmates, which while lower than reports from larger urban areas, is nevertheless 4–5 times the HIV prevalence in the general population (0.4%) [22]. The low HIV prevalence in prisons compared to others studies may be related to the decrease in intravenous drug use [23]. In 2006–2007, a survey was conducted in three state prisons that were also included in our study (Estabelecimento Penal Feminino Irmã Irma Zorzi, Instituto Penal de Campo Grande and Estabelecimento Penal Jair Ferreira de Carvalho); this study found that 10% of inmates were IDUs, and overall prevalence was 5% [24]. Similar prevalence of IDU and HIV was found in other Brazilian prisons during the last decade [7, 17]. These data may be in contrast to other prison settings, where injection drug use remains an important factor in HIV infection among inmates [25]. Declining HIV infection rates have been reported in some penal systems [26, 27]; however, global data are sparse, and better, representative data are needed to understand trends in disease burden in prisons and their drivers.

In the 2013 UNODC World Drug Report, 14.0 million people between the ages of 15 and 64 were estimated to be injecting drugs, while 1.6 million people who inject drugs were estimated to be living with HIV. This reflects a 12% decline in the number of people who inject drugs and a 46% decline in the number of people who inject drugs that are living with HIV since the 2008 estimates [28, 29].

An increasing number of countries have introduced HIV programmes in prisons since the early 1990s, but many of them are small in scale, restricted to a few prisons. Despite WHO and the Ministry of Health of Brazil recommend HIV testing for all prisoner at the time of incarceration for over 10 years [4, 30, 31], several studies among prisoners reported low testing rates (35%-84%) [17, 32, 33] and lack of awareness of HIV status among infected individuals (20%-65%) [8, 32, 34]. These findings demonstrate low adherence to these recommendations and critical need to implement routine testing programs in prison environments. The difficulty related to implementing such programs maybe in part due to the stigma associated with HIV status in the prisons. Human rights and privacy need to be protected, and policies against discrimination on the basis of HIV status need be monitored and enforced; a recent study highlighted the need for such provisions for prisoners in Brazil [35].

In addition to early diagnosis and treatment, other preventive measures are necessary to achieve more effective control of HIV in prisons. These include: prevention and treatment of STIs, treatment of drug dependence, needle and syringe exchange programs, condom distribution, health education, prevention of sexual violence, provision of safe practices for tattooing and piercing, and availability of post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV [4].

The results of this study have several limitations. Ten percent of inmates declined to participate in the study, and it’s possible that this group was at differential risk for HIV. We had limited access to clinical data on HIV-infected individuals, particularly with regard to the level of CD4, other co-infections and antiretroviral resistance. We performed serologic testing for syphilis but were unable to perform RPR or FTA-ABS to confirm active cases. While all HIV-infected participants were informed of their diagnosis, we were unable to reach 34% of those with a new HIV diagnosis at the time of attempted follow up six months after the initial survey. The short duration of incarceration was the primary reason for this challenge, which both limits the interpretation of linkage to care results and highlights the important area of transitional medical care that merits further work. Finally, the findings of present study may not be generalizable to other epidemiological situations, as the prevalence of injecting drug use was very low in our study in comparison with elsewhere in Brazil.

Conclusion

In Brazil, it is estimated that approximately 718,000 people are living with HIV/AIDS, among whom 20% are currently undiagnosed [36]. Despite the recognition of prison inmates as a high-risk population, we found an even higher proportion of undiagnosed HIV in this group. These results, along with prior studies from Brazil, indicate that HIV testing should be offered upon admission to all prisoners. Incarceration provides an opportunity for diagnosis and treatment of HIV and other STIs among this vulnerable population who often has poor access to health services outside of prison. Given the high rates and short duration of incarceration, and the high proportion of undiagnosed HIV, interventions among inmates may in fact reach a considerable portion of the underserved HIV-infected population in Brazil.

Supporting Information

(CSV)

Data Availability

Data are available from the UFGD Institutional Data Access / Ethics Committee for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Funding Statement

This work received support from the following sources: Fundação de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento do Ensino, Ciência e Tecnologia do Estado do Mato Grosso do Sul (FUNDECT, 0067/2012, http://fundect.ledes.net/) and the Ministry of Education (PROEXT 2014,http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=12243:proextapresentacao&catid=235:proext-programa-de-extensao-universitaria-&Itemid=487), Secretary of Health Surveillance (SVS/MS—20/2013). AIK received support from the Brazilian National Research Council (Ciências sem Fronteiras Program, http://www.cienciasemfronteiras.gov.br/web/csf), and AIK and JRA received support from Fogarty Global Health Equity Scholars Program (NIH 1 R25 TW009338, http://ghes.berkeley.edu/).

References

- 1. Walmsley R. World prison population list King's College London, International Centre for Prison Studies, 10 ed 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.ICPS. International Centre for Prison Studies. World prison brief. 2014. Available: http://www.prisonstudies.org/info/worldbrief/.

- 3.DEPEN, Ministério da Justiça. Secretaria Nacional de Justiça. Departamento Penitenciário Nacional. Sistema Integrado de informações Penitenciárias (InfoPen). [Integrated Penitentiary information] 2012. Available: http://portal.mj.gov.br/main.asp?View=%7BD574E9CE-3C7D-437A-A5B6-22166AD2E896%7D&Team=¶ms=itemID=%7BBFB720E2-BEF5-4C9E-8CC8-8B19506AE444%7D;&UIPartUID=%7B2868BA3C-1C72-4347-BE11-A26F70F4CB26%7D.

- 4. World Health Organization, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. HIV prevention, treatment and care in prisons and other closed settings: a comprehensive package of interventions Geneva: WHO, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Spaulding A, Stephenson B, Macalino G, Ruby W, Clarke JG, Flanigan TP. Human immunodeficiency virus in correctional facilities: a review. Clin Infect Dis. 2002. August 1;35(3):305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jurgens R, Nowak M, Day M. HIV and incarceration: prisons and detention. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14:26 10.1186/1758-2652-14-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Strazza L, Azevedo RS, Carvalho HB, Massad E. The vulnerability of Brazilian female prisoners to HIV infection. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004. May;37(5):771–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Poulin C, Alary M, Lambert G, Godin G, Landry S, Gagnon H, et al. Prevalence of HIV and hepatitis C virus infections among inmates of Quebec provincial prisons. CMAJ. 2007. July 31;177(3):252–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Catalan-Soares BC, Almeida RT, Carneiro-Proietti AB. Prevalence of HIV-1/2, HTLV-I/II, hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), Treponema pallidum and Trypanosoma cruzi among prison inmates at Manhuacu, Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2000. Jan-Feb;33(1):27–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berra JAP, Bacetti LB, Buzo AA. Soroprevalência de HIV, sífilis, hepatite B e C em mulheres do Centro de Ressocialização Feminino, Rio Claro, São Paulo; [Seroprevalence of HIV, syphilis, and hepatites B and C among women confined at Centro de Ressocialização Feminino of Rio Claro, São Paulo] Rev Inst Adolfo Lutz. 2006;65(2):133–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gough E, Kempf MC, Graham L, Manzanero M, Hook EW, Bartolucci A, et al. HIV and hepatitis B and C incidence rates in US correctional populations and high risk groups: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:777 10.1186/1471-2458-10-777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Almeida MC, de Jesus Pedroso N, do Socorro Lina van Keulen M, Jacome GP, Fernandes GC, Yokoo EM, et al. Loss to follow-up in a cohort of HIV-infected patients in a regional referral outpatient clinic in Brazil. AIDS Behav. 2014. December;18(12):2387–96. 10.1007/s10461-014-0812-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Lemos LM, Duarte GS, Martins NG, da Silva FJ, Ilozue C, Gurgel RQ. Estimating the number of HIV-positive pregnant women in Sergipe, Brazil, using capture-recapture. AIDS Care. 2013;25(6):691–4. 10.1080/09540121.2013.764389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Effectiveness of interventions to address HIV in prisons Geneva: WHO, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Albuquerque AC, da Silva DM, Rabelo DC, de Lucena WA, de Lima PC, Coelho MR, et al. [Seroprevalence and factors associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and syphilis in inmates in the state of Pernambuco, Brazil]. Cien Saude Colet. 2014. July;19(7):2125–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Burattini M, Massad E, Rozman M, Azevedo R, Carvalho H. Correlation between HIV and HCV in Brazilian prisoners: evidence for parenteral transmission inside prison. Rev Saude Publica. 2000. October;34(5):431–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coelho HC, Perdona GC, Neves FR, Passos AD. HIV prevalence and risk factors in a Brazilian penitentiary. Cad Saude Publica. 2007. September;23(9):2197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Osti NM, Castro AF, Ricci LC. Human immunodeficiency virus seroprevalence among inmates of the penitentiary complex of the region of campinas, state of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999. Jul-Aug;94(4):479–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marins JR, Page-Shafer K, Barros MBA, Hudes ES, Chen S, Hearst N. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors for HIV infection among incarcerated Men in Sorocaba, Brazil. AIDS and behavior, vol. 4 No 1, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20. El Maerrawi I, Carvalho HB. Prevalence and risk factors associated with HIV infection, hepatitis and syphilis in a state prison of Sao Paulo. Int J STD AIDS. 2015. February;26(2):120–7. 10.1177/0956462414531242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gabe C, Lara GM. Prevalência de anti-HCV, anti-HIV e co-infecção HCV/HIV em um presídio feminino do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul. RBAC, vol. 40(2):87–89,2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de DST, Aids e Hepatites Virais. Política Brasileira de enfrentamento da AIDS: Resultados, Avanços e Perspectivas. [Of coping with AIDS Brazilian Politics: Results, Progress and Perspectives]. Brasília, 2012.

- 23. Burattini MN, Strazza L, Paoliello AA, de Carvalho HB, de Azevedo RS, Coutinho FA, et al. The change from intravenous to crack cocaine and its impact on reducing HIV incidence in Brazilian prisons. Int J STD AIDS. 2005. December;16(12):836–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Francisco RBL. Infecção pelo vírus da Imunodeficiência Humana (HIV) na população prisional de Campo Grande, Mato grosso do Sul: caracterização Epidemiológica e Molecular Campo Grande: Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do sul, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jurgens R, Ball A, Verster A. Interventions to reduce HIV transmission related to injecting drug use in prison. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009. January;9(1):57–66. 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70305-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Haghdoost AA, Mirzazadeh A, Shokoohi M, Sedaghat A, Gouya MM. HIV trend among Iranian prisoners in 1990s and 2000s; analysis of aggregated data from HIV sentinel sero-surveys. Harm Reduct J. 2013;10:32 10.1186/1477-7517-10-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maruschak LM. HIV in Prisons, 2001–2010. U.S Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs. Bureau of Justice Statistics; September 2012, NCJ 238877. [Google Scholar]

- 28. UNODC. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report. United Nations, New York, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Strathdee SA, et al. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet. 2008. November 15;372(9651):1733–45. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61311-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas. Plano Nacional de Saúde no Sistema Penitenciário. [Health National Plan in the Penitentiary System]. 2. ed. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31. World Health Organization, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. HIV testing and counselling in prison and other closed settings Geneva: WHO, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Macgowan R, Margolis A, Richardson-Moore A, Wang T, Lalota M, French PT, et al. Voluntary rapid human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing in jails. Sex Transm Dis. 2009. February;36(2 Suppl):S9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rodriguez-Diaz CE, Rivera-Negron RM, Clatts MC, Myers JJ. Health Care Practices and Associated Service Needs in a Sample of HIV-Positive Incarcerated Men in Puerto Rico: Implications for Retention in Care. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014. January 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Semaille C, Le Strat Y, Chiron E, Chemlal K, Valantin MA, Serre P, et al. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus among French prison inmates in 2010: a challenge for public health policy. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(28). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reis CB, Bernardes EB. [What happens behind bars: prevention strategies developed in civilian police stations against HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases]. Cien Saude Colet. 2011. July;16(7):3331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de DST, Aids e Hepatites Virais. Boletim epidemiológico HIV AIDS. [Epidemiological Bulletin HIV AIDS] Ano II n° 01. Brasília, 2013

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(CSV)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the UFGD Institutional Data Access / Ethics Committee for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.